Abstract

Background/Aims

In capsule endoscopy (CE), the capsule does not always reach the cecum within its battery life, which may reduce its diagnostic yield. We evaluated the effect of mosapride citrate, a 5-hydroxytryptamine-4 agonist that increases gastrointestinal motility, on CE completion.

Methods

In a retrospective study, we performed univariate and multivariate analyses for 232 CE procedures performed at our hospital. To identify factors that affect CE completion, the following data were systematically collected: gender, age, gastric transit time (GTT), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug administration, previous abdominal surgery, hospitalization, use of a polyethylene glycol solution, use of mosapride citrate (10 mg), body mass index (BMI), and total recording time.

Results

The univariate analysis showed that oral mosapride citrate, GTT, and BMI were associated with improved CE completion. Multivariate analyses showed that oral mosapride citrate (odds ratio [OR], 1.99; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01 to 3.91) and GTT (OR, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.13 to 4.87) were significant factors for improving the CE completion. Oral mosapride citrate significantly shortened the GTT and small bowel transit time (SBTT).

Conclusions

Oral mosapride citrate reduced the GTT and SBTT during CE and improved the CE completion rate.

Keywords: Capsule endoscopy, Mosapride, Prokinetics

INTRODUCTION

Capsule endoscopy (CE) was developed in 20001 and has been useful for investigating obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB)2 and other small intestinal conditions.3,4 To improve the diagnostic yield of CE, examination of the entire small intestine is required. However, the examinations in about 20% of small intestinal CE procedures are incomplete, probably due to longer retention of the capsule in the stomach.5 To shorten the gastric transit time (GTT), various interventions have been reported, such as the administration of prokinetics.6-10 However, the results of these reports were conflicting, and the effects of these drugs on CE completion were not determined.

Mosapride citrate (Gasmotin; Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) is a prokinetic agent that acts as a 5-hydroxytryptamine-4 (5-HT4) agonist and increases gastrointestinal motility.11 Wei et al.12 conducted small pilot study and reported the effects of mosapride citrate on GTT and small intestinal transit time during CE. The primary end-point of this study was to elucidate the factors that affect CE completion. The second end-point was to evaluate the effect of mosapride citrate on CE completion rate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

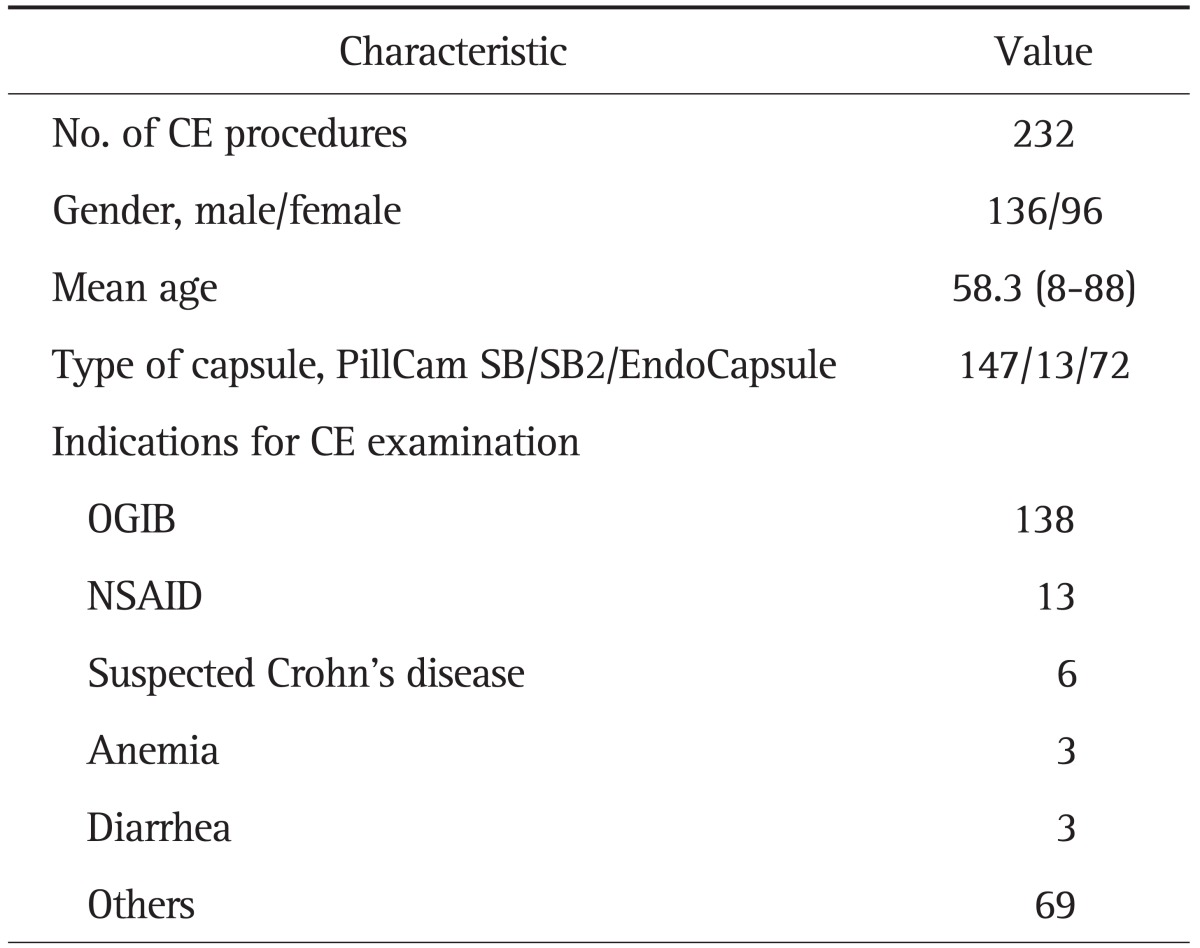

1. Enrolled patients and CE procedure

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients, and the study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of Keio University Hospital. From February 2004 to March 2010, 286 CE were consecutively performed in our hospital. We excluded 54 CE procedures (another clinical trial, 37; post-total gastrectomy, 5; retention in the stomach, 2; retention in the small bowel, 2; could not swallow the capsule, 2; recorder malfunction, 2; and missing medical records, 4). A total of 232 CE procedures were enrolled in this study. The characteristics of the study groups are shown in Table 1. The most common indication for CE was OGIB. CE was performed with the PillCam SB or SB2 capsule (Given Imaging, Tokyo, Japan) or the EndoCapsule (Olympus Medical systems, Tokyo, Japan) after a 12-hour fasting period. Of the 232 patients, 51 (22.0%) underwent bowel cleansing with 1 to 2 L of polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution before swallowing the capsule. In addition, 126 patients (54.3%) received oral mosapride citrate (10 mg) 30 to 60 minutes before they swallowed the capsule. After 8 to 16 hours, the recorder was disconnected, sensors were removed, and recorded digital information was downloaded from the recorder and transferred to the computer. The resultant images were reviewed by using the Rapid software version 5 (Given Imaging, Tokyo, Japan) or Olympus EndoCapsule software version 1 (Olympus Medical systems). The video images of CE were analyzed by 2 well-trained endoscopists (N. H., M. N.), who had previously reviewed more than 150 CE videos. In case of discrepancy in relevant findings, the differences were resolved with consensus. In each procedure, the GTT, small-bowel transit time (SBTT), and whether the examination was completed (capsule reaching the cecum) were recorded. GTT was defined as the time interval between the first gastric image and the first duodenal image. SBTT was defined as the time interval between the first duodenal image to the first cecal image. Completion rate was defined as the percentage of CE procedures in which the capsule reached the cecum. The positive findings were categorized according to standard terminology, as angiectasia, ulcer, bleeding of unknown origin, erosion, polyp/tumor, submucosal tumor, varix, and lymphangiectasia.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Groups

CE, capsule endoscopy; OGIB, obscure gastrointestinal bleeding; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

2. Study design

We determined whether the following potential factors were systematically collected from the patients' medical records: 1) gender, 2) age, 3) GTT, whether subdivided into more than 45-minute intervals, 4) use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), 5) previous abdominal surgery, 6) hospitalization, 7) use of PEG solution, 8) use of mosapride citrate (10 mg), 9) body mass index (BMI), and 10) total recording time. The collected data were analyzed by univariate and multivariate analyses. To evaluate the effect of the oral administration of mosapride citrate on gastrointestinal motility, the GTT and the SBTT of the capsule were compared between the control group and mosapride administration group by univariate analysis.

3. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using Student's t-test for normally distributed continuous variables, Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables that were not normally distributed, and the chi-square test for categorical variables. To identify factors that affect the completion of CE examinations, all potential factors were examined using univariate analysis. The relevant risk factors were determined by univariate analysis, and were subsequently entered in a logistic regression model for multivariate analysis. Odds ratios (ORs) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained for all significant variables. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. PASW version 17 software (SPSS Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan) was used in all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

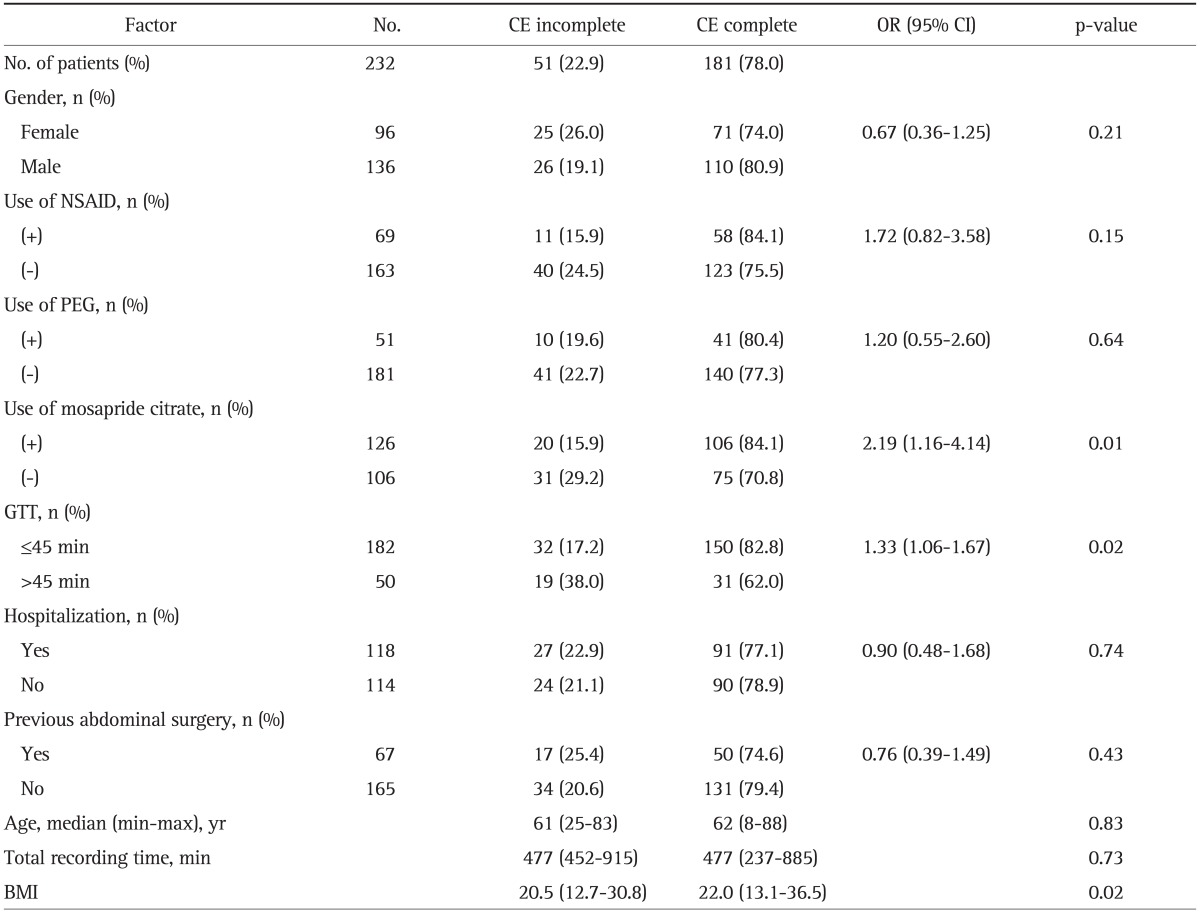

Of the 232 CE procedures, 181 (78%) were completed. The results of the univariate analyses of all factors that might affect the completion of small intestinal examinations are shown in Table 2. The factors associated with complete examinations were oral mosapride citrate administration (OR, 2.19; p=0.01), GTT less than 45 minutes (OR, 1.33; p=0.02), and BMI (p=0.02).

Table 2.

Univariate Analysis of Factors Affecting the Capsule Endoscopy Completion Rate

CE, capsule endoscopy; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PEG, polyethylene glycol; GTT, gastric transit time; BMI, body mass index.

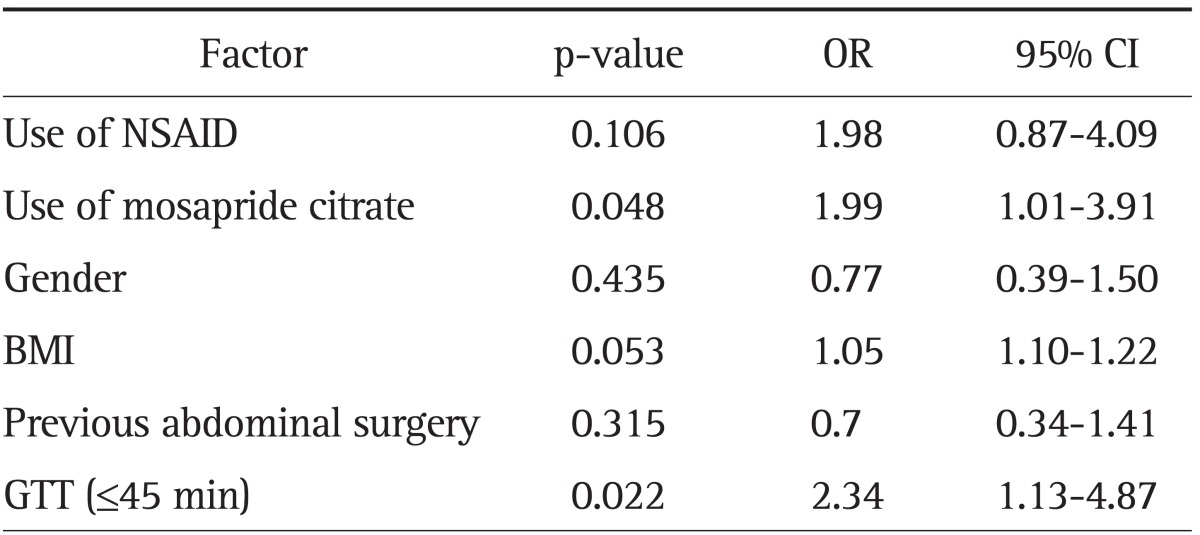

All significant factors found by univariate analysis and those factors that were thought to be related to the completion of CE examinations were analyzed by multivariate regression analysis. The results of multivariate analysis are shown in Table 3. Mosapride citrate and GTT less than 45 minutes were shown to be independent predictors of CE examination completion, whereas NSAID, gender, BMI, and previous surgery were not significant variables.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Analysis of Factors Affecting Capsule Endoscopy Completion Rate

Significance of model: χ2=21.072, p=0.002.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; BMI, body mass index; GTT, gastric transit time.

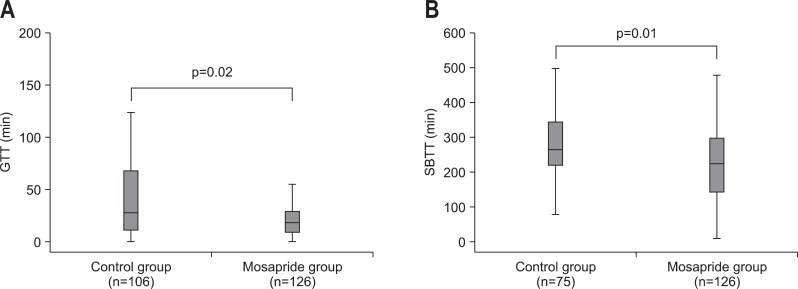

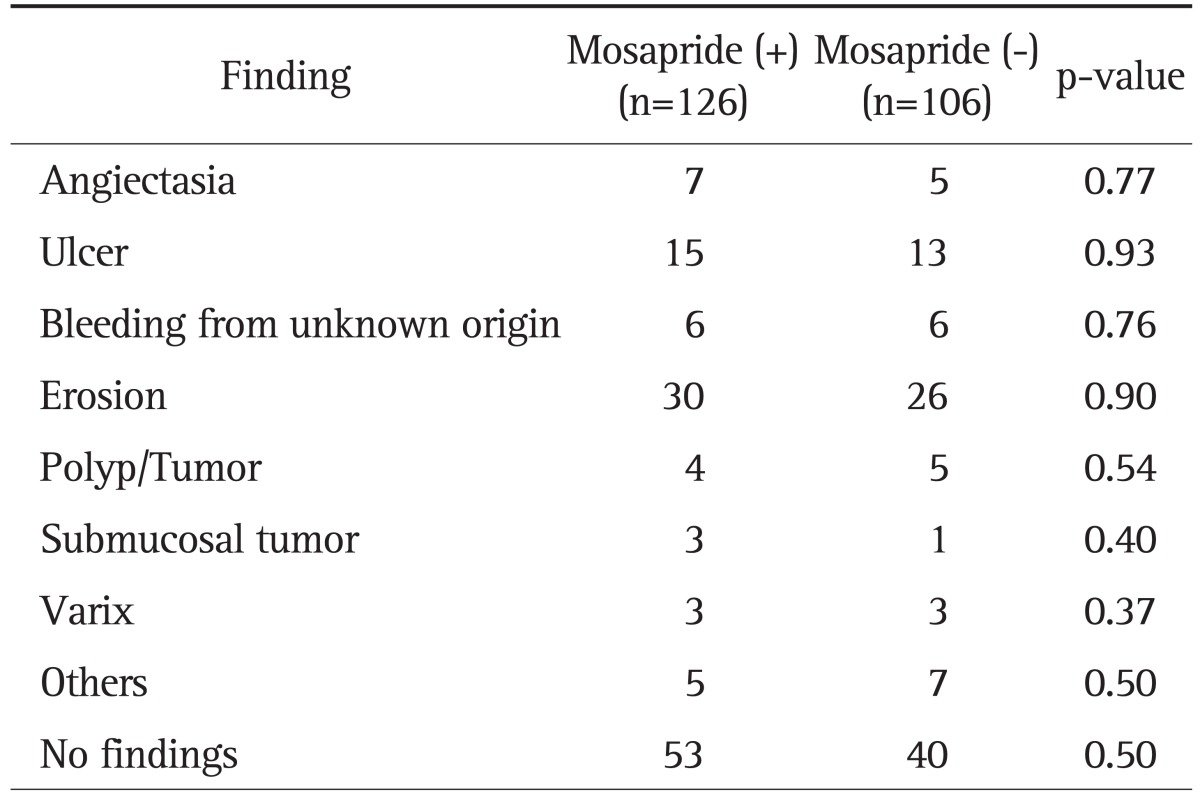

In the transit time analysis, GTT was significantly shorter in the mosapride citrate administration group than in the control group (p=0.02) (Fig. 1A). The median GTT was 18 minutes in the mosapride citrate administration group and 27.5 minutes in the non-administration group. The SBTT was also shorter in the mosapride citrate administration group than the non-administration group (p=0.01) (Fig. 1B). The median SBTT was 223 minutes in the mosapride citrate group and 266 minutes in the non-administration group. Although the SBTT was shorter in the mosapride citrate administration group than in the non-administration group, the number of positive findings was not significantly different between the two groups (Table 4). The number of patients with underlying disease was similar in both groups (the number of diabetic patients was 7 in the mosapride citrate administration group, 7 in the non-administration group, and 3 vs 4 of hemodialyzed patients). Hence, no medication which had a marked effect on the gastric or intestinal motility was administrated in both the groups.

Fig. 1.

(A) Effects of the administration of mosapride citrate on gastric transit time (GTT). The GTT was significantly shorter in the mosapride group than in the control (p=0.02). The median GTT was 30 minutes in the mosapride administration group and 56 minutes in the non-administration group. The data are presented in a box-and-whisker plot. The box includes those results falling between the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the median value is represented as a horizontal line inside the box (outliers and extremes are not shown). (B) Effects of the administration of mosapride citrate on small bowel transit time (SBTT). The SBTT of the capsule was significantly shorter in the mosapride group compared with the control (p=0.01). The median SBTT was 231 minutes in the mosapride administration group and 279 minutes in the non-administration group. The data are presented in a box-and-whisker plot. The box includes those results falling between 25th and 75th percentiles, and the median value is represented as a horizontal line inside the box (outliers and extremes are not shown).

Table 4.

Number of Positive Findings between the Mosapride Administration and Control Groups

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated the effect of oral mosapride citrate on CE completion and GTT. Previous reports have suggested that GTT affects CE completion.2,5,13,14 Moreover, other factors, such as aging,15,16 diabetes mellitus,14 hospitalization,16 and previous abdominal surgery17 were found to be associated with incomplete CE. We confirmed that mosapride citrate administration and GTT less than 45 minutes were independent predictors of the CE examination completion according to a logistic regression model. All of the above mentioned analyses, including ours, were retrospective. Therefore, each study analyzed a different population and included some bias. However, our analysis revealed that mosapride citrate administration and GTT less than 45 minutes were strong predictors of CE completion. Westerhof et al.13 found that a GTT cutoff value of 45 minutes was the most significant for discriminating between incomplete and complete CE examinations. In addition, the oral administration of mosapride citrate increased CE completion rate by 15%, and the adjusted OR for CE completion in cases with oral mosapride treatment was 1.99 (95% CI, 1.01 to 3.91).

The effects of prokinetics, such as erythromycin18 and metoclopramide,6,9 on CE have been studied previously; however, the results of these studies were conflicting. The sample size in these studies was 50 to 150 cases. Our data suggest that prospective studies with 100 samples have a power of about 40%. Consequently, β errors will occur in 60% of these results. Although our study was retrospective, the effectiveness of mosapride citrate on CE completion should be confirmed using an adequate number of samples.

The effect of mosapride citrate on CE completion was evaluated by Wei et al.12 prospectively by using 60 samples. Their pilot study showed that the completion rates of the mosapride group and control group were 93.33% (28/30) and 66.66% (20/30), respectively, and the difference between the two groups was significant. However, we found that the completion rates of the mosapride group and control group were 84.1% and 70.8%; hence, to achieve 80% power at 5% level of significance, the required sample size should be 121 in each group, i.e., total sample size of 242. Therefore, a large sample is needed to confirm the effect of mosapride citrate on CE completion.

The administration of mosapride reduced GTT and SBTT. This confirmed that serotonin 5-HT4 receptors are located in the stomach as well as the small intestine. Reduction in GTT improved the completion rate of CE. Meanwhile, reduction in SBTT might reduce the diagnostic yield of small bowel disease. Our data showed that the oral administration of mosapride citrate improved the CE completion rate, and the diagnostic yield of small bowel disease was not significantly different between the two groups (Table 4).

Mosapride citrate is a 5-HT4 agonist that is available in Asia. Tegaserod, another 5-HT4 agonist, is available in the Western countries. Previous studies using tegaserod19,20 have shown conflicting results. However, our data suggests that tegaserod also has the potential to improve the completion rate of CE.

In conclusion, mosapride administration and GTT less than 45 minutes were independent predictors of CE completion; oral mosapride citrate, a serotonin 5-HT4 receptor agonist, reduced the GTT and SBTT. However, a prospective randomized trial involving 250 samples is required to confirm the usefulness of this prokinetic agent.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Y. I. is supported by a grant from The Japanese Foundation for the Research and Promotion of Endoscopy. N. H. is supported by The Research fund of Mitsukoshi Health and Welfare Foundation.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Iddan G, Meron G, Glukhovsky A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Nature. 2000;405:417. doi: 10.1038/35013140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selby W. Complete small-bowel transit in patients undergoing capsule endoscopy: determining factors and improvement with metoclopramide. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:80–85. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02462-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albert JG, Martiny F, Krummenerl A, et al. Diagnosis of small bowel Crohn's disease: a prospective comparison of capsule endoscopy with magnetic resonance imaging and fluoroscopic enteroclysis. Gut. 2005;54:1721–1727. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.069427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trifan A, Singeap AM, Cojocariu C, Sfarti C, Stanciu C. Small bowel tumors in patients undergoing capsule endoscopy: a single center experience. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Soussan E, Savoye G, Antonietti M, Ramirez S, Lerebours E, Ducrotté P. Factors that affect gastric passage of video capsule. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:785–790. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almeida N, Figueiredo P, Freire P, et al. The effect of metoclopramide in capsule enteroscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:153–157. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0687-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalantzis C, Triantafyllou K, Papadopoulos AA, et al. Effect of three bowel preparations on video-capsule endoscopy gastric and small-bowel transit time and completeness of the examination. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:1120–1126. doi: 10.1080/00365520701251601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leung WK, Chan FK, Fung SS, Wong MY, Sung JJ. Effect of oral erythromycin on gastric and small bowel transit time of capsule endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4865–4868. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i31.4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogata H, Kumai K, Imaeda H, et al. Clinical impact of a newly developed capsule endoscope: usefulness of a real-time image viewer for gastric transit abnormality. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:186–192. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2140-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Postgate A, Tekkis P, Patterson N, Fitzpatrick A, Bassett P, Fraser C. Are bowel purgatives and prokinetics useful for small-bowel capsule endoscopy? A prospective randomized controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1120–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okamura K, Sasaki N, Yamada M, Yamada H, Inokuma H. Effects of mosapride citrate, metoclopramide hydrochloride, lidocaine hydrochloride, and cisapride citrate on equine gastric emptying, small intestinal and caecal motility. Res Vet Sci. 2009;86:302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei W, Ge ZZ, Lu H, Gao YJ, Hu YB, Xiao SD. Effect of mosapride on gastrointestinal transit time and diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1605–1608. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westerhof J, Weersma RK, Koornstra JJ. Risk factors for incomplete small-bowel capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Triantafyllou K, Kalantzis C, Papadopoulos AA, et al. Video-capsule endoscopy gastric and small bowel transit time and completeness of the examination in patients with diabetes mellitus. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:575–580. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papadopoulos AA, Triantafyllou K, Kalantzis C, et al. Effects of ageing on small bowel video-capsule endoscopy examination. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2474–2480. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scaglione G, Russo F, Franco MR, Sarracco P, Pietrini L, Sorrentini I. Age and video capsule endoscopy in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: a prospective study on hospitalized patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1188–1193. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Endo H, Matsuhashi N, Inamori M, et al. Abdominal surgery affects small bowel transit time and completeness of capsule endoscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1066–1070. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0467-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niv E, Bonger I, Barkay O, et al. Effect of erythromycin on image quality and transit time of capsule endoscopy: a two-center study. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2561–2565. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmelkin IJ. Tegaserod decreases small bowel transit times in patients undergoing capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:P176. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim KJ, Kim SH, Rho EJ. Tegaserod increase colonic entry rate in patients undergoing capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:AB170. [Google Scholar]