Abstract

Objective To estimate the burden of melanoma resulting from sunbed use in western Europe.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources PubMed, ISI Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded), Embase, Pascal, Cochrane Library, LILACS, and MedCarib, along with published surveys reporting prevalence of sunbed use at national level in Europe.

Study selection Observational studies reporting a measure of risk for skin cancer (cutaneous melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma) associated with ever use of sunbeds.

Results Based on 27 studies ever use of sunbeds was associated with a summary relative risk of 1.20 (95% confidence interval 1.08 to 1.34). Publication bias was not evident. Restricting the analysis to cohorts and population based studies, the summary relative risk was 1.25 (1.09 to 1.43). Calculations for dose-response showed a 1.8% (95% confidence interval 0% to 3.8%) increase in risk of melanoma for each additional session of sunbed use per year. Based on 13 informative studies, first use of sunbeds before age 35 years was associated with a summary relative risk of 1.87 (1.41 to 2.48), with no indication of heterogeneity between studies. By using prevalence data from surveys and data from GLOBOCAN 2008, in 2008 in the 15 original member countries of the European Community plus three countries that were members of the European Free Trade Association, an estimated 3438 cases of melanoma could be attributable to sunbed use, most (n=2341) occurring among women.

Conclusions Sunbed use is associated with a significant increase in risk of melanoma. This risk increases with number of sunbed sessions and with initial usage at a young age (<35 years). The cancerous damage associated with sunbed use is substantial and could be avoided by strict regulations.

Introduction

Exposure to the sun is the most important environmental cause of skin cancer, with the wavelength for ultraviolet radiation associated with development of the disease.1 The wavelengths for ultraviolet radiation range between 100 nm and 400 nm and are broadly categorised into ultraviolet A light (315-400 nm), ultraviolet B (280-315 nm), and ultraviolet C (100-280 nm). All ultraviolet C and most ultraviolet B wavelengths are blocked by the stratospheric ozone layer. A fraction of ultraviolet B and all ultraviolet A reaches the Earth’s surface.

In light skinned populations, the ultraviolet radiation delivered by sunbeds has become the main non-solar source of exposure to ultraviolet light. Indoor tanning has been widely practised in northern Europe and the United States since the 1980s,2 and since 2000 this trend has gained popularity in sunnier countries, such as Australia.3 4 Modern indoor tanning equipment mainly emits in the ultraviolet A range, but a fraction (<5%) of this spectrum is in the ultraviolet B range. This ultraviolet B fraction induces a deep, long lasting tan. Powerful ultraviolet tanning units may be 10-15 times stronger than the midday sunlight on the Mediterranean Sea, and repeated exposure to large amounts of ultraviolet A delivered to the skin in relatively short periods (typically 10-20 minutes) constitutes a new experience for humans.

Indoor tanning has a plethora of negative health effects, many of which are involved in cancerous processes.5 The impact of this trend on incidence of skin cancer is of concern, mainly because of cutaneous malignant melanoma, a cancer of poor prognosis when diagnosed at an advanced stage.

Until recently ultraviolet B was usually considered the only carcinogenic fraction of the solar spectrum reaching the Earth’s surface. In 2009, the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified the whole ultraviolet spectrum and indoor tanning devices as carcinogenic to humans (group 1).6 The rationale for classifying ultraviolet A and sunbeds as group 1 carcinogens was based on congruent lines of evidence from basic and epidemiological research. Briefly, extensive laboratory data and animal experiments (on DNA mutations and repair, immune function, cell integrity, cell cycle regulation, and other critical biological functions) documented a role for ultraviolet A in skin carcinogenesis7 8 9 and that the body’s repair and removal of damaged DNA was less effective when the damage was caused by ultraviolet A rather than by ultraviolet B.10 Experiments in human volunteers showed that exposure to ultraviolet A and ultraviolet B can weaken the immune system through mechanisms that interact and overlap, increasing vulnerability to cancer as well as to other diseases.11 Also, tanning lamps induce the types of DNA damage to the skin associated with photocarcinogenesis.11 Lastly, the meta-analysis undertaken in 2005 found a significant 75% increase in risk of melanoma (from 40% to 228%) when indoor tanning started during adolescence or young adulthood.11 12 Some evidence was also found that indoor tanning increased the risk of squamous cell carcinoma, especially when sunbed use started before the age of 20.

The meta-analysis by the International Agency for Research on Cancer in 2006 could not examine dose-responses, and additional epidemiological studies published since then have provided an opportunity for some aspects of the relation between sunbed use and melanoma to be explored in greater depth. Using meta-analysis we quantified the risk of melanoma associated with indoor tanning using artificial ultraviolet light, including dose-response and the estimated burden of melanoma and death associated with sunbed use in western Europe.

Methods

To update the meta-analysis of 2006, we used the same methodological approach as previously described.11 Briefly, MB searched the literature published up to May 2012 using the databases PubMed, ISI Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded), Embase, Pascal, Cochrane Library, LILACS, and MedCarib. We used the following keywords for diseases: “skin cancer”, “squamous cell carcinoma”, “SCC”, “basal cell carcinoma”, “BCC”, and “melanoma”. To define exposure, we used the following keywords: “sunbed”, “sunlamp”, “artificial UV”, “artificial light”, “solaria”, “solarium”, “indoor tanning”, “tanning bed”, “tanning parlour”, “tanning salon”, and “tanning booth”. No language restriction was applied. We reviewed the titles and abstracts to identify potentially eligible studies and carried out a manual search of studies identified from references cited in reviews on skin cancer.

From the initial search we selected case-control, cohort, and cross sectional studies published as original articles. Non-eligible trials included ecological studies, case reports, reviews, and editorials.

PA and SG reviewed the selected articles and SG and MB abstracted the data using a standardised data collection protocol. The minimal common information on use of indoor tanning appliances for all studies was “ever used.” For those studies that did not strictly assess ever users of indoor tanning appliances compared with never users,13 14 we used the information closest to this category.

We also extracted the highest category of sunbed use reported in each study—that is, the greater duration (defined as “high use”) along with estimates of risk for the association with first use of sunbeds at a young age—before age 35 years.

Statistical analysis

We transformed every measure of association, adjusted for the maximum number of confounding variables, and 95% confidence intervals, into logarithms of relative risk and calculated the corresponding variance.15 When no estimates were reported, we used tabular data to calculate the crude estimates and 95% confidence intervals.

The meta-analysis was calculated from a random effect model as described previously16—that is, a mixed effects model with summary relative risk obtained from maximum likelihood estimation. We calculated confidence intervals assuming an underlying t distribution. Heterogeneity was assessed by Higgins and Thompson’s I2 statistic.17 The I2 statistic ranges from zero to 100%, zero indicating that the relative risks of the different studies included in the meta-analysis are homogeneous—that is, that the relative risks are consistent with each other.

We used a two step procedure to obtain summary risk estimates for dose-response. Firstly, we fitted a linear model within each study to estimate the relative risk per session of sunbed use. When sufficient information was published (the number of participants in usage category), we fitted the model according to a previously proposed method.18 This method provides the natural logarithm of the relative risk and an estimator of its standard error, taking into account that the estimates for separate categories depend on the same reference group. When the numbers of participants in each serum level category were not available from the publications, we calculated coefficients ignoring the correlation between the estimates of risk at the separate exposure levels. Secondly, we estimated the summary relative risk by pooling the study specific estimates with the mixed effects models.

All analyses were done with SAS Windows version 9.2. We used PROC MIXED in SAS to calculate the random effects models.

Heterogeneity and sensitivity analyses

We carried out several sensitivity analyses to evaluate the stability of the pooled estimates. Firstly we examined the pooled relative risks for case-control and prospective (cohort and nested case-control) studies separately. Then we examined changes to the results after the exclusion of specific studies.

To investigate heterogeneity between the studies we carried out metaregressions and subgroup analyses. Heterogeneity was investigated by looking at factors that could influence the quality of the studies and that could be responsible for heterogeneity, such as the study design, adjustment for confounding factors, features of the population, and publication year. As an additional analysis for heterogeneity, we compared risk estimates according to the average latitude of countries or areas where studies were done.

To investigate whether publication bias may have affected the validity of the estimates, we constructed funnel plots of the regression of log relative risk on the sample size, weighted by the inverse of the pooled variance. We evaluated publication bias using the Macaskill test.19

Sunbed use and burden of melanoma

To translate the estimation of risk in the current study to the burden in the general population, we provided a broad estimation of the burden of sunbed use in Europe. We gathered data on the prevalence of sunbed use from recent surveys carried out in Europe. As no survey was available for central European countries, we limited our estimation to the original 15 countries of the European Community (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Spain, Sweden, Portugal, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom) plus the three countries that are part of the European Free Trade Association (Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland). For these 18 countries, we extracted data on the incidence of melanoma from GLOBOCAN 2008.20

We identified seven surveys carried out in the 18 countries from which we extracted prevalence of ever having used a sunbed during lifetime.21 22 23 24 25 26 27 We also extracted the prevalence of sunbed use in the control group included in the Swedish cohort.14 Data were available for Denmark, France, Germany, Iceland, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. These countries represent 70% of all melanoma cases occurring in the 18 countries studied. Prevalence for the other 10 countries was determined from estimates for neighbouring countries.

We estimated the attributable fraction with Levin’s formula28 by using prevalence of ever use of sunbeds from surveys and the summary relative risk for ever use of sunbeds.

Results

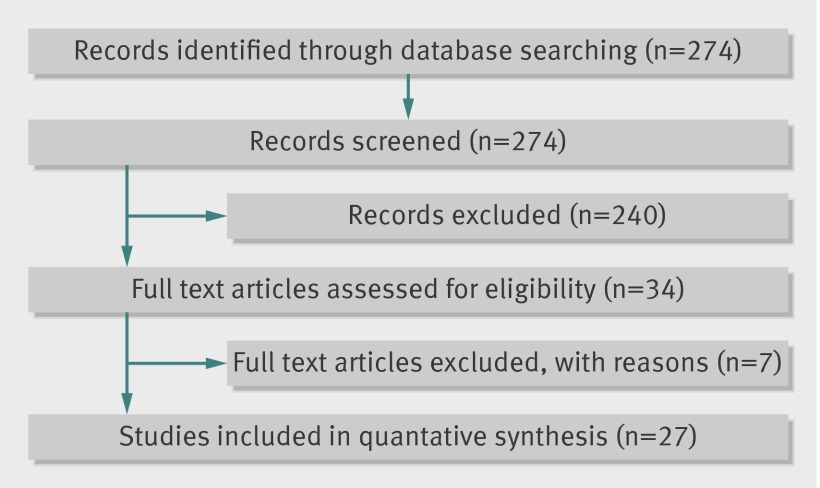

Figure 1 describes the literature search process. Since the meta-analysis of 2006, eight additional studies were identified, one of which was the update of the Norwegian-Swedish cohort.29 Thus in May 2012, 32 studies had investigated the relation between sunbed use and melanoma (table 1). All studies were based on the case-control design except three, which were cohort studies.14 50 59 The Nurse’s Health Study was based on a cohort design but the trial was a case-control study with retrospective assessment of sun exposure and sunbed use in samples of skin cancer cases and controls matched on year of birth.42 One study was a survey among patients attending a dermatology clinic.53 One third of patients participated in the survey. Sunbed use of patients with a diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma was compared with that of other patients. Although this study was not in the broadest sense a case-control design, it was included in the meta-analysis.

Fig 1 Flow of studies on sunbed use and risk of cutaneous melanoma

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies on sunbed use and melanoma considered for meta-analysis

| Studies | Country | No of cases | No of controls | Adjustments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort or population based case-control studies: | ||||

| Adam et al 198130 | UK | 169 | 207 | Crude |

| Gallagher et al 198640* | Canada | 595 | 595 | — |

| Holman et al 198645 | Australia | 511 | 511 | Crude |

| Osterlind et al 198851 | Denmark | 474 | 926 | Not clear |

| Zanetti et al 198858 | Italy | 208 | 416 | Age, hair colour, skin reaction, sunburn in childhood, education level |

| Beitner et al 199034* | Sweden | 523 | 505 | — |

| Walter et al 199055*† | Canada | 583 | 608 | — |

| Westerdahl et al 199457 | Sweden | 400 | 640 | Hair colour, nevi, skin type, sunburns |

| Holly et al 199543 | USA | 452 | 930 | — |

| Chen et al 199835 | USA | 624 | 512 | Age, sex, phenotype, recreational sun exposure |

| Walter et al 199954 | Canada | 583 | 608 | Age, sex, and skin reaction |

| Westerdahl et al 200056 | Sweden | 571 | 913 | Sunburns, hair colour, sunbathing |

| Han et al 200642 | USA | 200 | 804 | |

| Clough-Gorr et al 200836 | USA | 423 | 678 | Age, sex, family history, hair colour, sun exposure |

| Cust et al 201137 | Australia | 604 | 479 | — |

| Lazovich et al 201047 | USA | 1167 | 1101 | Age, sex, family history, hair colour, sun exposure |

| Veierød et al 201014 | Norway, Sweden | 412 | 106 366‡ | Age, residence, hair colour, sunburns, annual “bathing” holiday |

| Elliott et al 201139 | UK | 959 | 513 | Age, sex, educational level, family history of melanoma, sun sensitivity, and sun exposure |

| Nielsen et al 201150 | Sweden | 210 | 29 520‡ | Crude |

| Zhang et al 201259 | USA | 349 | 73 494‡ | Age, family history, hair colour, number of moles, sunburn tendency and history, outdoor sun exposure, ultraviolet index, state of residence at birth, age 15, and age 30 |

| Other case-control studies: | ||||

| Klepp and Magnus 197946* | Norway | 78 | 131 | — |

| Holly et al 198744* | USA | 121 | 139 | — |

| Swerdlow et al 198852 | UK | 180 | 120 | Crude |

| MacKie et al 198948 | UK | 280 | 180 | Nevi, skin type, sunburn, freckles, tropical residence |

| Dunn-Lane et al 199338 | UK | 100 | 100 | Crude |

| Garbe et al 199341 | Germany | 280 | 280 | Nevi, hair type, and phototype§ |

| Autier et al 199431 | Multicentre | 420 | 447 | Crude |

| Naldi et al 200049 | Italy | 542 | 538 | Age, sex, skin, hair, eye, nevi, freckles, sunburns, number of holidays in sunny climates |

| Kaskel et al 200113 | Germany | 271 | 271 | Crude |

| Bataille et al 200433 | UK | 413 | 416 | Sex and age |

| Bataille et al 200532 | Belgium, France, Netherlands, Sweden, UK | 597 | 622 | Sex, age, and skin phototype§ |

| Ting et al 200753 | USA | 29 | 307 | Not clear |

*Not included in main meta-analysis as no estimate of risk was reported.

†1990 study was reanalysed in 1999. Present meta-analysis uses relative risk adjusted for potential confounders presented in 1999 publication.

‡Cohort size.

§Sensitivity to sunlight.

Four of the 32 studies13 14 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 were excluded from the meta-analysis because they did not include estimates of the relative risk for cutaneous melanoma associated with sunbed use.34 44 46 40 One study55 was redundant as it was reanalysed and published in 1999.54

Studies used for meta-analysis totalled 11 428 cases of melanoma. The first study30 was published in 1981 and the last59 in 2012. Eighteen studies were carried out in European countries, seven in the United States and Canada, and two in Australia.

Summary relative risks

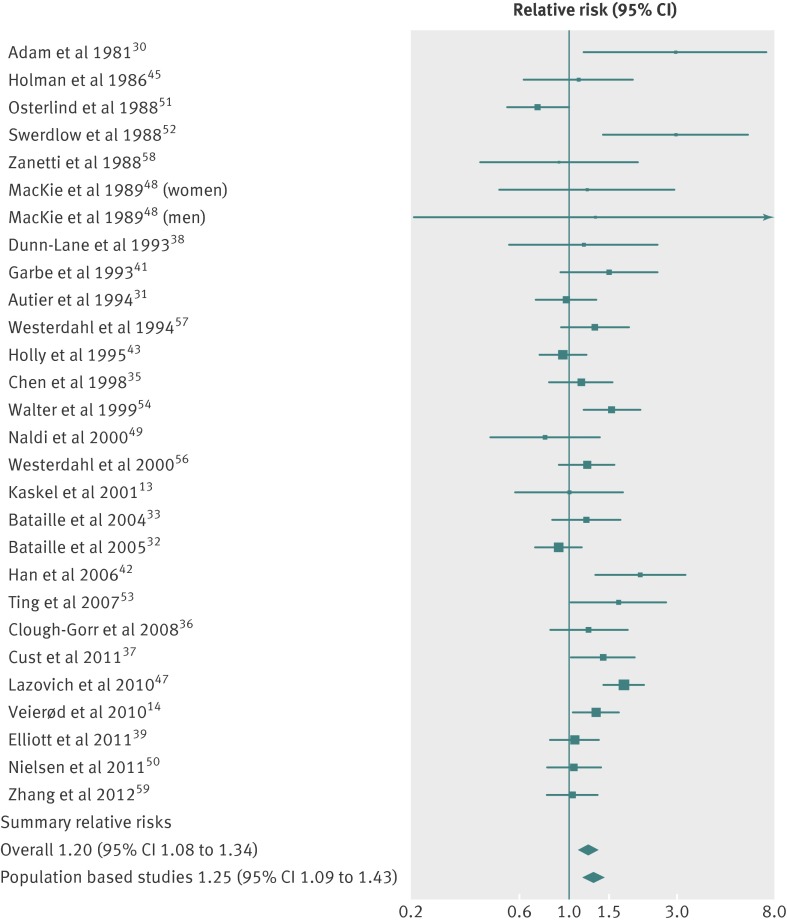

Twenty seven studies presented positive estimates for ever use compared with never use of sunbeds (fig 2). Eight of these studies reported only crude relative risks and one adjusted for age and sex only. The summary relative risk was 1.20 (95% confidence interval 1.08 to 1.34), with heterogeneity (I2=56%). Evidence of publication bias was lacking (P=0.99, Macaskill test). An analysis restricted to the 18 cohort and population based case-control studies produced a slightly higher summary relative risk (1.25, 1.09 to 1.43). An analysis restricted to the 18 studies that adjusted for confounders related to sun exposure and sun sensitivity yielded a similar summary relative risk (1.29, 1.13 to 1.48).

Fig 2 Forest plot of risk for melanoma associated with ever use of sunbeds. Heterogeneity I²=57% for all studies combined

When the cohort studies were excluded from the analysis the summary relative risk decreased slightly but remained statistically significant (1.20, 1.06 to 1.37).

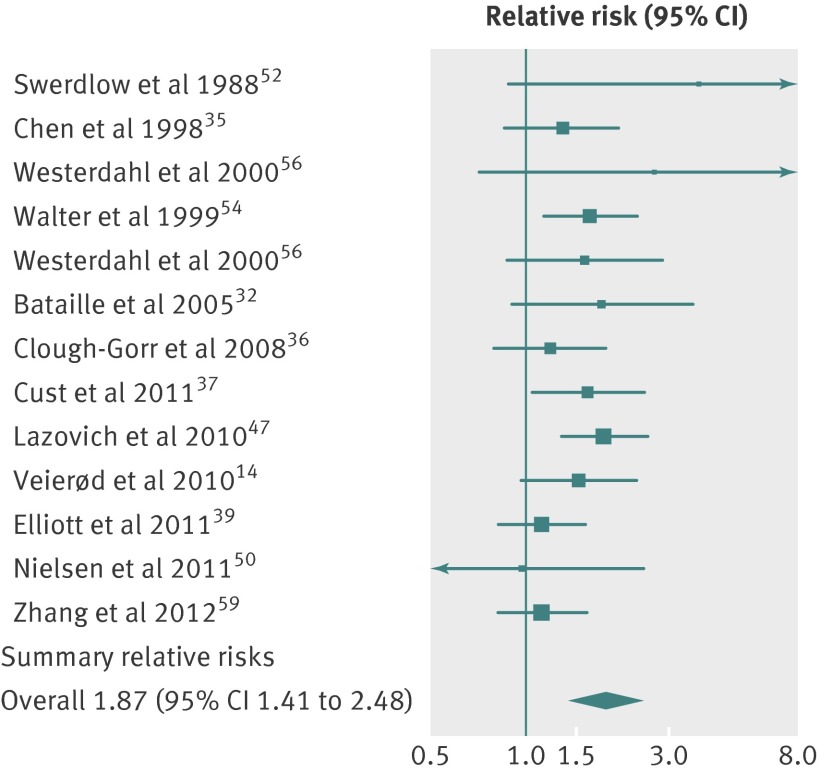

Thirteen studies presented estimates relevant for the evaluation of first use of sunbeds in youth (before age 35) compared with never use (fig 3). All relative risks were adjusted for confounders related to sun exposure or sun sensitivity, except in one study.54 The risk was almost doubled (relative risk 1.87), with no indication of heterogeneity (I2=0).

Fig 3 Forest plot of risk for melanoma associated with ever use of sunbeds when first use was before age 35 years. No heterogeneity (I2=0)

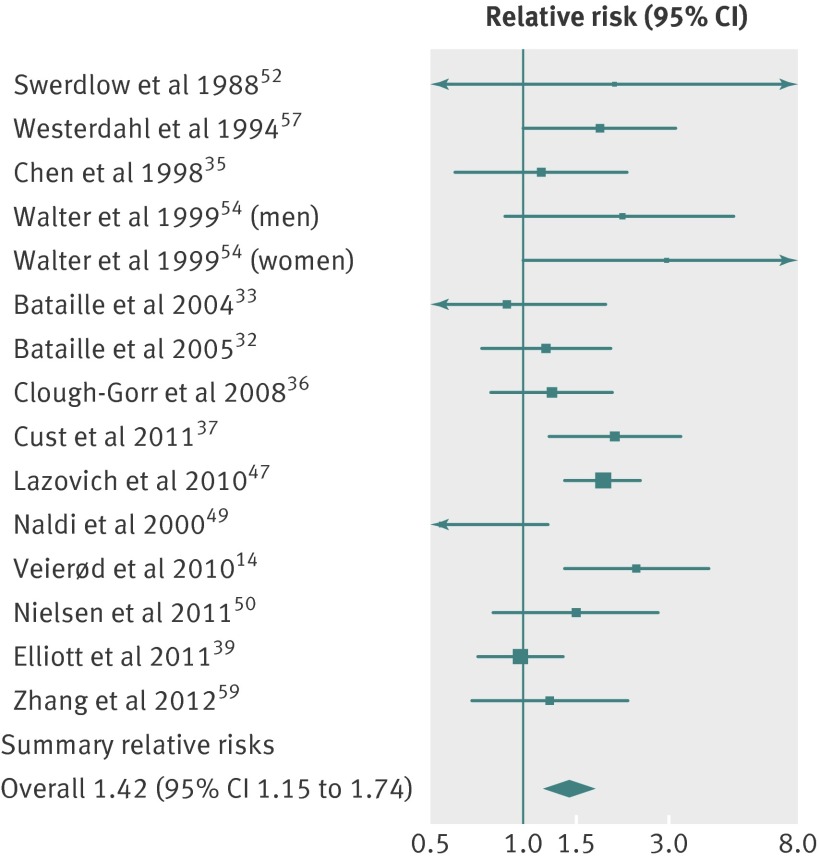

Four studies reported data on risk associated with the number of sunbed sessions per year. A summary relative risk derived from relative risks reported for each session was 1.018 (95% confidence interval 0.998 to 1.038), which indicated a 1.8% increase in risk of melanoma for each annual session. A significant 42% increased risk was found for high use of sunbeds (summary relative risk 1.42, 95% confidence interval 1.15 to 1.74; fig 4). Nine studies reported risks associated with time since first use, with first use distant in time (that is, more than five years before diagnosis) associated with a higher summary relative risk (1.49, 1.18 to 1.88; I2=34%) than first use more recently (1.18, 0.95 to 1.48; I2=51%, table 2).

Fig 4 Forest plot of risk for melanoma associated with high use of sunbeds. Heterogeneity I²=47%

Table 2.

Summary relative risks found by meta-analyses on sunbed use and cutaneous melanoma

| Sunbed use | No of studies in 2005 meta-analysis* | Summary relative risk (95% CI) | No of studies in present meta-analysis | Summary relative risk (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ever use | 19 | 1.15 (1.00 to 1.31) | 27 | 1.20 (1.08 to 1.34) | 56 |

| Ever use† | 10 | 1.17 (0.96 to 1.42) | 18 | 1.25 (1.09 to 1.43) | 60 |

| First use in youth (<35 years) | 7 | 1.75 (1.35 to 2.26) | 13 | 1.87 (1.41 to 2.48) | 0 |

| High use | NR | NR | 14 | 1.42 (1.15 to 1.74) | — |

| First use recently | 5 | 1.10 (0.76 to 1.60) | 9 | 1.18 (0.95 to 1.48) | 51 |

| First use distant in time‡ | 5 | 1.49 (0.93 to 2.38) | 9 | 1.49 (1.18 to 1.88) | 34 |

NR=not reported.

*International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2006.

†Cohort or population based case-control studies only.

‡More than five years before diagnosis.

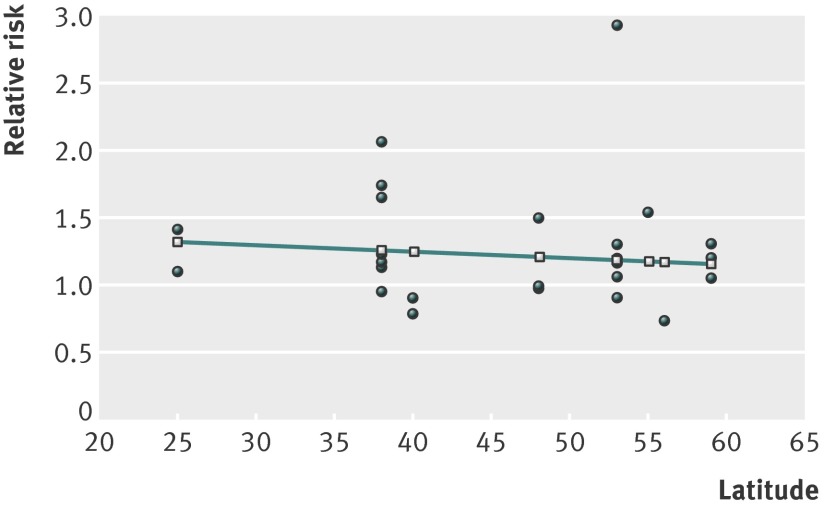

Risks for sunbed related melanoma were compared in populations living at different latitudes (fig 5). Relative risks associated with ever versus never use of sunbeds did not differ much with variations in latitude and there was no indication that risks would be higher in more sun sensitive populations such as those in the Nordic countries.

Fig 5 Risk for melanoma associated with ever use of sunbeds as a function of latitude

Sensitivity analysis

The summary relative risk remained significant when all possible studies, including publications with missing estimates, were included and a relative risk of 1 (no effect) was imputed for the missing relative risks (1.20, 1.10 to 1.34).

Squamous and basal cell carcinomas

Two studies42 59 published since 2005 looked at the risk of non-melanoma skin cancer associated with sunbed use. Adding data from this study to that of the 2006 meta-analysis11 yielded summary relative risks for ever versus never sunbed use of 2.23 (1.39 to 3.57) for squamous cell carcinoma (1242 cases in five studies)42 59 60 61 62 and 1.09 (1.01 to 1.18) for basal cell carcinoma (6995 cases in six studies).42 59 61 62 63 64

Impact on burden of melanoma in western Europe

Of 63 942 new cases of cutaneous melanoma diagnosed each year in the 15 countries that were members of the European Community and the three countries that were part of the European Free Trade Association, an estimated 3438 (5.4%) were related to sunbed use (table 3). Women represented most of this burden, with 2341 cases (6.9% of all melanoma cases in women) related to sunbed use; 1096 cases annually occurred in men (3.7% of all cases in men). Taking a melanoma incidence to mortality ratio of 3.7 for European men and 4.7 for European women,20 in the 15 European Community countries, about 498 women and 296 men would die each year from a melanoma as a result of being exposed to indoor tanning using artificial ultraviolet light.

Table 3.

Estimation of number of melanoma cases attributed to sunbed use in Europe

| Population | Attributable fraction (%)* | Incidence case caused by ever use of sunbeds | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Total | ||

| Austria† | 6.5 | 10.6 | 34 | 52 | 86 | |

| Belgium† | 6.5 | 10.6 | 41 | 102 | 143 | |

| Denmark | 8.1 | 13.0 | 52 | 106 | 157 | |

| Finland‡ | 5.8 | 9.4 | 29 | 43 | 72 | |

| France | 1.4 | 3.8 | 47 | 157 | 203 | |

| Germany | 6.5 | 10.6 | 500 | 904 | 1404 | |

| Greece§ | 0.4 | 1.3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |

| Iceland | 3.9 | 6.1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Ireland | 1.6 | 5.8 | 5 | 25 | 30 | |

| Italy§ | 0.4 | 1.3 | 15 | 52 | 67 | |

| Luxembourg† | 6.5 | 10.6 | 2 | 4 | 6 | |

| Norway‡ | 5.8 | 9.4 | 38 | 57 | 95 | |

| Portugal§ | 0.4 | 1.3 | 1 | 7 | 8 | |

| Spain | 0.4 | 1.3 | 6 | 26 | 32 | |

| Sweden | 5.8 | 9.4 | 71 | 113 | 184 | |

| Switzerland | 5.1 | 8.7 | 54 | 101 | 155 | |

| Netherlands† | 6.5 | 10.6 | 114 | 231 | 345 | |

| United Kingdom | 1.6 | 5.8 | 87 | 357 | 444 | |

| Total | 1096 | 2341 | 3438 | |||

*Calculated from relative risk determined in present meta-analysis and various surveys on prevalence of sunbed use in population.

†Prevalence data for Germany were used for Austria, Luxembourg, Belgium, and Netherlands.

‡Prevalence data for Sweden were used for Finland and Norway. As no data were reported for men, we applied the male:female ratio from Germany survey to Sweden prevalence data.

§Prevalence data for Spain were used for Greece, Italy, and Portugal.

Discussion

Overall, the summary of results of 27 observational studies published within the past 30 years shows that the risk of cutaneous melanoma is increased by 20% for those who were ever users of indoor tanning devices with artificial ultraviolet light. The risk of melanoma was doubled when use started before the age of 35 years. This latest estimate originates from studies in various populations and latitudes, which obtained consistent results with zero heterogeneity. Summary risk estimates calculated from population based case-control studies were close to those of cohort studies.

Comparison with 2006 evaluation

The 2006 evaluation11 did not find evidence for a dose-response relation between the level of sunbed use and risk of melanoma; however, a formal metaregression analysis could not be carried out because not enough data were published at that time. Since then, large studies have provided data consistent with a dose-response relation—for example, a study in Minnesota47 found dose-responses for years during which sunbeds were used, cumulative time (hours) of sunbed use, and cumulative number of tanning sessions.

Table 2 summarises the results of the meta-analyses of 200611 and of this meta-analysis. From 2005 to 2011, most summary relative risks have increased. These changes support the hypothesis that earlier studies tended to underestimate risks associated with indoor tanning because this behavioural trend is relatively new and thus recent uses may not (yet) have influenced the incidence of melanoma.11 65 From this logic it is possible that future epidemiological studies on sunbed use and skin cancer could show relative risks higher than those found to date.

Risk of melanoma associated with sunbed use in different populations

We did not observe a significant difference in risk when taking latitude of residence into account. Most studies included in this meta-analysis were adjusted for phototype or a proxy for sun sensitivity. In this respect, the summary relative risks presented in this article are valid for all light skinned populations such as those in Europe, North America, and Australasia. The number of melanoma cases arising from sunbed use may, however, be higher than we estimated because it seems that sunbed users are more likely to have fair skin, have red or blond hair, have more freckles, and be phototype I/II (burn easily and tan minimally if at all when first exposed to the sun) than III/IV (burn moderately and tan easily or always when first exposed to the sun) than non-users.66

Sunbed users also have the tendency to adopt unhealthy lifestyles compared with non-users2 and we could hypothesise that use of sunbeds may be a marker of populations more exposed to sun. However, several studies, such as the cohort study by Veierød et al14 (see table 1), did adjust for a variable of sun exposure. The summary relative risk is then unlikely to reflect a more intense exposure to sun among sunbed users. Compelling evidence that use of sunbeds can be a cause of melanoma and not just a proxy for sun exposure arises from the investigation of a melanoma epidemic in Iceland, a country located between 64° and 66° N and where sunny days are uncommon.67 After 1990, the incidence of melanoma increased sharply, mainly in young women, with preferential occurrence on the trunk. The incidence tended to decline after 2000, when public health authorities imposed greater control on sunbed installation and utilisation. Although that study was an ecological one, the exposure of Icelandic youngsters that took place after 1985 seemed to be the most likely reason for that epidemic.68

The results of this meta-analysis are in full agreement with the considerable amount of data pointing to childhood and adolescence as the key periods for initiation and development of melanoma in adulthood.69 This evidence on the risks of skin cancer associated with exposure to ultraviolet light at young ages underlines the health threats documented by many recent surveys, which show substantial use by children and adolescents of tanning devices using artificial ultraviolet light in the United States and European countries,70 71 72 73 with evidence for unabated increasing use in the United States.74 For instance, in Denmark, a survey completed in 2008 found that 2% of children aged 8 to 11 years and 13% aged 12 to 14 years had used a sunbed within the past 12 months.72

Burden of melanoma associated with sunbed use in Europe

In Europe, 71% of melanoma cases in 2008 occurred in the 15 European Union countries and the three European Free Trade Association countries. We estimated that in these 18 countries each year, around 3438 new cases of melanoma and 794 related deaths would be related to sunbed use. This estimation is limited to western European countries because of a lack of information on sunbed use in central European countries. The number of deaths from melanoma associated with sunbed use was determined for the United Kingdom in 2003,75 with an estimated 100 deaths (range 50-200) annually. Our calculation of attributable fractions would put the number of deaths for the United Kingdom at 99, a figure consistent with the earlier estimate. The estimation of deaths from melanoma should be treated with caution since some epidemiological data suggest that, on average, sunbed related melanoma could be of low malignant potential.75 76 None the less, the burden of cancer attributable to sunbed use could further increase in the next 20 years because the recent, high usage levels observed in many countries have not yet achieved their full carcinogenic effect and because usage levels of teenagers and young adults remain high in many countries. This prediction is supported by the observation over 10-15 years of increases in the incidence of melanoma on the trunks of women from countries with widespread access to indoor tanning.67 77 78 79 80 The incidence rates of trunk melanoma in women aged 20-49 years therefore could be a relevant indicator for monitoring activities to decrease the use of sunbeds.

Indoor tanning industry and regulation

Melanoma and other skin cancers that are specifically associated with sunbed use are preventable diseases by avoiding exposure to these devices. Generally the sunbed industry has not self regulates effectively and has tended to disseminate non-evidence based information, which can deceive consumers.81 82 83 Tanning salon operators simply following regulations is an illusory prevention method, as such regulations are unable to turn a carcinogenic agent into a healthy one. Instead, the sunbed industry has used the opportunity to claim that properly regulated indoor tanning is safe, and that it might even have health benefits.81

Discouraging sunbed use or requiring parental authorisation is not effective, partly because many parents of teenagers willing to use sunbeds are also sunbed users themselves.2 73

Prevention of the harmful effects associated with sunbed use must be based on tougher actions. Recommendations from the World Health Organization, the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP), and the European Society of Skin Cancer Prevention (EUROSKIN) maintain that the highest regulatory priorities should be the restriction of sunbed use by people under 18 years of age and the banning of unsupervised indoor tanning facilities. Such restrictions have now been implemented in Australia and in several European countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Portugal, Scotland, and Spain). In the United States, until the recent ban by the state of California issued on 10 October 2011, no state had banned access to indoor tanning for adolescents aged less than 18 years.

If sunbed use by teenagers and young adults does not substantially decrease in the short term, then more radical actions should be envisioned, such as the nationwide prohibition of the public use of tanning devices, which was implemented by the Brazilian National Health Surveillance Agency84 in November 2009.85

What is already known on this topic

Earlier studies suggested an increased risk of melanoma, in particular when sunbed use started before age 35

No consistent dose-response relation was found

What this study adds

This study confirms a doubling of the risk of melanoma when first sunbed use is at a young age (<35 years)

A dose-response relation exists between amount of sunbed use and risk of melanoma

In Europe each year, 3438 new cases of melanoma would be due to sunbed use

Contributors: MB, SG, and PA carried out the literature search and extracted data. MB and SG did the statistical analysis and drafted the first manuscript. All authors interpreted the data, contributed to discussion, and reviewed or edited the manuscript. All authors take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis and are guarantors for the paper.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: The statistical analysis programs in SAS are available on request from the corresponding author (mathieu.boniol@i-pri.org).

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;345:e4757

References

- 1.International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Solar and ultraviolet radiation. Monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. No 55. IRAC, 1992. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Schneider S, Krämer H. Who uses sunbeds? A systematic literature review of risk groups in developed countries. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010;24:639-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paul CL, Girgis A, Tzelepis F, Walsh RA. Solaria use by minors in Australia: is there a cause for concern? Aust N Z J Public Health 2004;28:90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paul CL, Stacy F, Girgis A, Brozek I, Baird H, Hughes J. Solaria compliance in an unregulated environment: the Australian experience. Eur J Cancer 2005;41:1178-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim HW, James WD, Rigel DS, Maloney ME, Spencer JM, Bhushan R. Adverse effects of ultraviolet radiation from the use of indoor tanning equipment: time to ban the tan. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;64:893-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El Ghissassi F, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, Bouvard V, et al. A review of human carcinogens—part D: radiation. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:751-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ridley AJ, Whiteside JR, McMillan TJ, Allinson SL. Cellular and sub-cellular responses to UVA in relation to carcinogenesis. Int J Radiat Biol 2009;85:177-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rünger TM, Kappes UP. Mechanisms of mutation formation with long-wave ultraviolet light (UVA). Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2008;24:2-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mouret S, Forestier A, Douki T. The specificity of UVA-induced DNA damage in human melanocytes. Photochem Photobiol Sci 2011;11:155-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mouret S, Baudouin C, Charveron M, Favier A, Cadet J, Douki T. Cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers are predominant DNA lesions in whole human skin exposed to UVA radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:13765-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Exposure to artificial UV radiation and skin cancer. IARC working group reports No 1. IARC, 2006.

- 12.International Agency for Research on Cancer Working Group on Artificial Ultraviolet (UV) Light and Skin Cancer. The association of use of sunbeds with cutaneous malignant melanoma and other skin cancers: a systematic review. Int J Cancer 2007;120:1116-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaskel P, Sander S, Kron M, Kind P, Peter RU, Krahn G. Outdoor activities in childhood: a protective factor for cutaneous melanoma? Results of a case-control study in 271 matched pairs. Br J Dermatol 2001;145:602-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veierød MB, Adami H-O, Lund E, Armstrong BK, Weiderpass E. Sun and solarium exposure and melanoma risk: effects of age, pigmentary characteristics, and nevi. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:111-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenland S. Quantitative methods in the review of epidemiologic literature. Epidemiol Rev 1987;9:1-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Houwelingen HC, Arends LR, Stijnen T. Advanced methods in meta-analysis: multivariate approach and meta-regression. Stat Med 2002;21:589-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenland S, Longnecker MP. Methods for trend estimation from summarized dose-response data, with applications to meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 1992;135:1301-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macaskill P, Walter SD, Irwig L. A comparison of methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. Stat Med 2001;20:641-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. GLOBOCAN 2008 v1.2. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase No 10. International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2010.

- 21.Køster B, Thorgaard C, Philip A, Clemmensen I. Sunbed use and campaign initiatives in the Danish population, 2007-2009: a cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011;25:1351-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.INPES. Baromètre cancer 2010. 2011. www.inpes.fr.

- 23.Schneider S, Zimmermann S, Diehl K, Breitbart EW, Greinert R. Sunbed use in German adults: risk awareness does not correlate with behaviour. Acta Derm Venereol 2009;89:470-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sigurdsson T. Proceedings of the NSFS XV conference in Ålesund, Norway, 2008. The number and usage of sunbeds in Iceland 1988 and 2005. Icelandic Radiation Protection Institute, 2008.

- 25.Galán I, Rodríguez-Laso A, Díez-Gañán L, Cámara E. Prevalence and correlates of skin cancer risk behaviors in Madrid (Spain). Gac Sanit 2011;25:44-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.OFSP. Bulletin 15/11. 11 April 2011.

- 27.Boyle R, O’Hagan AH, Donnelly D, Donnelly C, Gordon S, McElwee G, et al. Trends in reported sun bed use, sunburn, and sun care knowledge and attitudes in a UK region: results of a survey of the Northern Ireland population. Br J Dermatol 2010;163:1269-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levin ML. The occurrence of lung cancer in man. Acta Unio Int Contra Cancrum 1953;9:531-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veierød MB, Weiderpass E, Thörn M, Hansson J, Lund E, Armstrong B, et al. A prospective study of pigmentation, sun exposure, and risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma in women. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003;95:1530-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adam SA, Sheaves JK, Wright NH, Mosser G, Harris RW, Vessey MP. A case-control study of the possible association between oral contraceptives and malignant melanoma. Br J Cancer 1981;44:45-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Autier P, Dore JF, Lejeune F, Koelmel KF, Geffeler O, Hille P, et al. Cutaneous malignant melanoma and exposure to sunlamps or sunbeds: for the EORTC multicenter case-control study in Belgium, France and Germany. Int J Cancer 1994;58:809-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bataille V, Boniol M, De Vries E, Severi G, Brandberg Y, Sasieni P, et al. A multicentre epidemiological study on sunbed use and cutaneous melanoma in Europe. Eur J Cancer 2005;41:2141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bataille V, Winnett A, Sasieni P, Newton-Bishop JA, Cuzick J. Exposure to the sun and sunbeds and the risk of cutaneous melanoma in the UK: a case-control study. Eur J Cancer 2004;40:429-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beitner H, Norell SE, Ringborg U, Wennersten G, Mattson B. Malignant melanoma: aetiological importance of individual pigmentation and sun exposure. Br J Dermatol 1990;122:43-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen YT, Dubrow R, Zheng T, Barnhill RL, Fine J, Berwick M. Sunlamp use and the risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma: a population-based case-control study in Connecticut, USA. Int J Epidemiol 1998;27:758-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clough-Gorr KM, Titus-Ernstoff L, Perry AE, Spencer SK, Ernstoff MS. Exposure to sunlamps, tanning beds, and melanoma risk. Cancer Causes Control 2008;19:659-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cust AE, Armstrong BK, Goumas C, Jenkins MA, Schmid H, Hopper JL, et al. Sunbed use during adolescence and early adulthood is associated with increased risk of early-onset melanoma. Int J Cancer 2011;128:2425-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunn-Lane J, Herity B, Moriarty MJ, Conroy R. A case control study of malignant melanoma. Ir Med J 1993;86:57-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elliott F, Suppa M, Chan M, Leake S, Karpavicius B, Haynes S, et al. Relationship between sunbed use and melanoma risk in a large case-control study in the United Kingdom. Int J Cancer 2012;130:3011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gallagher RP, Elwood JM, Hill GB. Risk factors for cutaneous malignant melanoma: the Western Canada Melanoma Study. Recent Results Cancer Res 1986;102:38-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garbe C, Weiss J, Kruger S, Garbe E, Buttner P, Bertz J, et al. The German melanoma registry and environmental risk factors implied. Recent Results Cancer Res 1993;128:69-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Han J, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ. Risk factors for skin cancers: a nested case-control study within the Nurses’ Health Study. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:1514-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holly EA, Aston DA, CressRD, Ahn DK, Kristiansen JJ. Cutaneous melanoma in women. I. Exposure to sunlight, ability to tan, and other risk factors related to ultraviolet light. Am J Epidemiol 1995;141:923-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holly EA, Kelly JW, Shpall SN, Chiu SH. Number of melanocytic nevi as a major risk factor for malignant melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;17:459-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holman CD, Armstrong BK, Heenan PJ, Blackwell JB, Cumming FJ, English DR, et al. The causes of malignant melanoma: results from the West Australian Lions Melanoma Research Project. Recent Results Cancer Res 1986;102:18-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klepp O, Magnus K. Some environmental and bodily characteristics of melanoma patients. A case-control study. Int J Cancer 1979;23:482-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lazovich D, Vogel RI, Berwick M, Weinstock M, Anderson KE, Warshaw EM. Indoor tanning and risk of melanoma: a case-control study in a highly exposed population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:1557-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.MacKie RM, Freudenberger T, Aitchison TC. Personal risk-factor chart for cutaneous melanoma. Lancet 1989;2:487-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Naldi L, Gallus S, Imberti GL, Cainelli T, Negri E, La Vecchia C, on behalf of the Italian Group for Epidemiological Research in Dermatology. Sunlamps and sunbeds and the risk of cutaneous melanoma. Eur J Cancer Prev 2000;9:133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nielsen K, Måsbäck A, Olsson H, Ingvar C. A prospective, population-based study of 40000 women regarding host factors, UV exposure and sunbed use in relation to risk and anatomic site of cutaneous melanoma. Int J Cancer 2012;131:706-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Osterlind A, Tucker MA, Stone BJ, Jensen OM. The Danish case-control study of cutaneous malignant melanoma. II. Importance of UV-light exposure. Int J Cancer 1988;42:319-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swerdlow AJ, English JS, MacKie RM, O’Doherty CJ, Hunter JA, Clark J, et al. Fluorescent lights, ultraviolet lamps, and risk of cutaneous melanoma. BMJ 1988;297:647-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ting W, Schultz K, Cac NN, Peterson M, Walling HW. Tanning bed exposure increases the risk of malignant melanoma. Int J Dermatol 2007;46:1253-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walter SD, King WD, Marrett LD. Association of cutaneous malignant melanoma with intermittent exposure to ultraviolet radiation: results of a case-control study in Ontario, Canada. Int J Epidemiol 1999;28:418-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Walter SD, Marrett LD, From L, Hertzman C, Shannon HS, Roy P. The association of cutaneous malignant melanoma with the use of sunbeds and sunlamps. Am J Epidemiol 1990;131:232-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Westerdahl J, Ingvar C, Masback A, Jonsson N, Olsson H. Risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma in relation to use of sunbeds: further evidence for UV-A carcinogenicity. Br J Cancer 2000;82:1593-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Westerdahl J, Olsson H, Masback A, Ingvar C, Jonsson N, Brandt L, et al. Use of sunbeds or sunlamps and malignant melanoma in southern Sweden. Am J Epidemiol 1994;140:691-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zanetti R, Rosso S, Faggiano F, Roffino R, Colonna S, Martina G. A case-control study of melanoma of the skin in the province of Torino, Italy. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 1988;36:309-17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang M, Qureshi AA, Geller AC, Frazier L, Hunter DJ, Han J. Use of tanning beds and incidence of skin cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1588-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aubry F, MacGibbon B. Risk factors of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Cancer 1985;55:907-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bajdik CD, Gallagher RP, Astrakianakis G, Hill GB, Fincham S, McLean DI. Non-solar ultraviolet radiation and the risk of basal and squamous cell skin cancer. Br J Cancer 1996;73:1612-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Karagas MR, Stannard VA, Mott LA, Slattery MJ, Spencer SK, Weinstock MA. Use of tanning devices and risk of basal cell and squamous cell skin cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Corona R, Dogliotti E, D’Errico M, Sera F, Iavarone I, Baliva G, et al. Risk factors for basal cell carcinoma in a Mediterranean population. Arch Dermatol 2001;137:1162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Walther U, Kron M, Sander S, Sebastian G, Sander R, Peter RU, et al. Risk and protective factors for sporadic basal cell carcinoma: results of a two-centre case-control study in southern Germany. Clinical actinic elastosis may be a protective factor. Br J Dermatol 2004;151:170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Autier P. Perspectives in melanoma prevention: the case of sunbeds. Eur J Cancer 2004;40:2367-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ezzedine K, Malvy D, Mauger E, Nageotte O, Galan P, Hercberg S, et al. Artificial and natural ultraviolet radiation exposure: beliefs and behaviour of 7200 French adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2008;22:186-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Héry C, Tryggvadóttir L, Sigurdsson T, Sigurdsson T, Ólafsdóttir E, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. A melanoma epidemic in Iceland: possible influence of sunbed use. Am J Epidemiol 2010;172:762-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alberg AJR. A melanoma epidemic in Iceland: possible influence of sunbed use. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Autier P, Boyle P. Artificial ultraviolet sources and skin cancers: rationale for restricting access to sunbed use before 18 years of age. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 2008;5:178-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cokkinides V, Weinstock M, Lazovich D, Ward E, Thun M. Indoor tanning use among adolescents in the US, 1998 to 2004. Cancer 2009;115:190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guy GP, Tai E, Richardson LC. Use of indoor tanning devices by high school students in the United States, 2009. Prev Chronic Dis 2011;8:A116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Krarup AF, Koster B, Thorgaard C, Philip A, Clemmensen IH. Sunbed use by children aged 8-18 years in Denmark in 2008: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol 2011;165:214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mayer JA, Woodruff SI, Slymen DJ, Sallis JF, Forster JL, Clapp EJ, et al. Adolescents’ use of indoor tanning: a large-scale evaluation of psychosocial, environmental, and policy-level correlates. Am J Public Health 2011;101:930-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Buller DB, Cokkinides V, Hall I, Hartman AM, Saraiya M, Miller E, et al. Prevalence of sunburn, sun protection, and indoor tanning behaviors among Americans: review from national surveys and case studies of 3 states. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;65:S114-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Diffey B. A quantitative estimate of melanoma mortality from ultraviolet A sunbed use in the UK. Br J Dermatol 2003;149:578-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Autier P, Doré JF, Eggermont AMM, Coebergh JW. Epidemiological evidence that the UVA radiation is involved in the genesis of cutaneous melanoma. Curr Opin Oncol 2011;23:189-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bradford PT, Anderson WF, Purdue MP, Goldstein AM, Tucker MA. Rising melanoma incidence rates of the trunk among younger women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:2401-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dal H, Boldemann C, Lindelöf B. Does relative melanoma distribution by body site 1960-2004 reflect changes in intermittent exposure and intentional tanning in the Swedish population? Eur J Dermatol 2007;17:428-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mowbray M, Stockton DL, Doherty VR. Changes in the site distribution of malignant melanoma in South East Scotland (1979-2002). Br J Cancer 2007;96:832-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Montella A, Gavin A, Middleton R, Autier P, Boniol M. Cutaneous melanoma mortality starting to change: a study of trends in Northern Ireland. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:2360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Autier P, Doré JF, Breitbart E, Greinert R, Pasterk P, Boniol M. The indoor tanning industry’s double game. Lancet 2011;377:1299-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Federal Trade Commission. Indoor tanning. FTC consumer alert, March 2010. www.ftc.gov/bcp/edu/pubs/consumer/alerts/alt174.pdf.

- 83.Greenman J, Jones DA. Comparison of advertising strategies between the indoor tanning and tobacco industries. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;62:685,e1-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.ANVISA. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária Resolução No 59 de 9 de novembro 2009. Proibe em todo território nacional o uso dos equipamentos para bronzeamento artificial, com finalidade estética, baseada na emissão da radiação ultraviolet (UV). Diário Oficial da União—Seção 1, No 215, quarta-feira, 11 de novembro de 2009. www.saude.mg.gov.br/atos_normativos/legislacao-sanitaria/RESOLUCaO%20RDC%2056.pdf.

- 85.Cumberland S, Jurberg C. From Australia to Brazil: sun worshippers beware. Bull World Health Organ 2009;87:574-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]