Abstract

Combining the structural elements of the second generation 2′-O-methoxyethyl (MOE) and locked nucleic acid (LNA) antisense oligonucleotide (AON) modifications yielded the highly nuclease resistant 2′,4′-constrained MOE and ethyl bicyclic nucleic acids (cMOE and cEt BNA, respectively). Crystal structures of DNAs with cMOE or cEt BNA residues reveal their conformational preferences. Comparisons with MOE and LNA structures allow insights into their favourable properties for AON applications.

Antisense oligonucleotides (AONs) bind to a target RNA using Watson-Crick recognition rules, and modulate RNA function in order to produce a pharmacological effect.1,2 A large number of chemical modifications have been investigated to improve the drug-like properties of AONs.2–5 Among them, antisense oligonucleotide drugs that contain the 2′-O-methoxyethyl (2’-O-MOE) modification (2, Fig. 1) have been particularly useful for the development of AON drugs.6,7 The MOE nucleotides improve affinity for target RNA and also stabilize the oligonucleotide from nuclease mediated degradation. Structural studies of an MOE modified RNA duplex showed that the methoxyethyl substituent is well hydrated and projects into the minor groove of the modified duplex, with the sugar ring rigidified in a C3′-endo sugar pucker.8 To further improve the affinity of MOE oligonucleotides for cognate RNA, we tethered the 2′-O-MOE substituent to the 4′-position of the furanose ring to provide the 2′,4′-constrained 2′-O-MOE modifications 5 (R-cMOE) and 6 (S-cMOE), respectively.9,10 The 2′,4′-constraint enforces a C3′-endo sugar pucker and improves affinity for RNA. This was first demonstrated in locked nucleic acid 4 (LNA), which essentially represents the 2′,4′-constrained version of 2′-O-methyl RNA 1.11,12

Figure 1.

Design of 2′–4′-conformationally restricted nucleosides from 2′-modified RNAs.

In addition, we also prepared 2′,4′-constrained 2′-O-ethyl modifications 7 [(R)-cEt] and 8 [(S)-cEt] which have reduced steric bulk but were expected to be less hydrated as compared to MOE and cMOE modified oligonucleotides. Biophysical evaluation of R- and S-cMOE and R- and S-cEt modified DNA revealed that these modifications showed similar enhancements in duplex thermal stability as observed for sequence-matched LNA oligonucleotides, but a greatly enhanced nuclease stability profile as compared to both LNA and MOE modified oligonucleotides.10 In addition, cEt and cMOE modified ASOs showed improved potency relative to MOE and an improved therapeutic profile relative to LNA ASOs in animal experiments.9 To help understand how the R- and S-configured methyl and methoxymethyl substituents in cEt and cMOE modified AONs contribute to their improved properties, we examined the crystal structures of cEt and cMOE modified oligonucleotides. In this communication, we present a detailed analysis of the crystal structures of cEt and cMOE modified duplexes and propose a steric origin for the improved nuclease stability exhibited by this class of nucleic acid analogs.

The cEt BNA and cMOE BNA nucleoside phosphoramidites were synthesized and incorporated into oligonucleotides as reported previously.10 Consistent with our previous studies on cEt, both cEt and cMOE BNA were shown to afford vastly improved protection against nucleases compared to MOE-RNA and LNA, with a >100-fold increase in half life observed in a snake venom phosphodiesterase assay (Table S1). For our crystallographic studies, we chose the decamer sequence 5′-d(GCGTAU*ACGC)-3′ with the individual modifications inserted at position 6 (bold font), as we previously found that this decamer adopts an A-form conformation if at least one of the 2′-deoxynucleotides is replaced with a 2′-modified residue.13 Furthermore, the structures of LNA as well as 2′-MOE RNA and multiple other 2′-modified AONs have been determined in this sequence, and these studies provided insight into the improved binding affinity and/or nuclease resistance of these modifications.14,15 Oligonucleotides 1–4 containing (S)-cEt BNA, (R)-cEt BNA, (S)-cMOE BNA, and (R)-cMOE BNA, respectively were synthesized and analyzed using liquid chromatography coupled mass spectrometry (Table 1).

Table 1.

(S)-cEt BNA, (R)-cEt BNA, (S)-cMOE BNA and (R)-cMOE BNA modified DNAs used in the crystallographic studies.

| No. | Sequence | Chemistry, U* | Calcd. Mass |

Found Mass |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5′-dGCGTAU*ACGC | (S)-cEt BNA | 3056.3 | 3055.2 |

| 2 | 5′-dGCGTAU*ACGC | (R)-cEt BNA | 3056.1 | 3055.4 |

| 3 | 5′-dGCGTAU*ACGC | (S)-cMOE BNA | 3086.1 | 3085.4 |

| 4 | 5′-dGCGTAU*ACGC | (R)-cMOE BNA | 3086.1 | 3085.5 |

The crystal structures of decamer duplexes with sequence d(GCGTAU*ACGC), whereby U* is (R)-cEt BNA-U, (S)-cEt BNA-U, or (S)-cMOE BNA-U were crystallized [see supporting information (SI)]†, and their structures determined at resolutions of between 1.42 and 1.68 Å.‡ No crystals were obtained for the decamer with (R)-cMOE BNA-U despite numerous attempts. Final electron densities are shown in SI Fig. S1 and crystal data and final refinement parameters are listed in SI Table S2. Nucleotides of one strand are numbered 1 to 10 and those in the complementary strand are numbered 11 to 20.

As expected all three duplexes adopt an A-form conformation. In the (R)-cEt BNA duplex, the average values for helical rise and twist are 2.9 Å and 31.7°, respectively, and they amount to 2.9 Å and 31.3°, respectively, in the (S)-cEt BNA duplex. All sugars in the two duplexes adopt a C3′-endo pucker. The backbone torsion angles of (R)-cEt BNA and (S)-cEt BNA nucleotides U*6 and U*16 fall into standard ranges (sc−/ap/sc+/sc+/ap/sc− for α to ζ; Fig. 2A,B). In the (R)-cEt BNA duplex, residues A5 and G19 residues display an extended variant of the backbone with torsion angles α and γ both in the ap range rather than the standard sc− and sc+ conformations, respectively. In the (S)-cEt BNA duplex, residues A5 and G13 display the extended conformation.

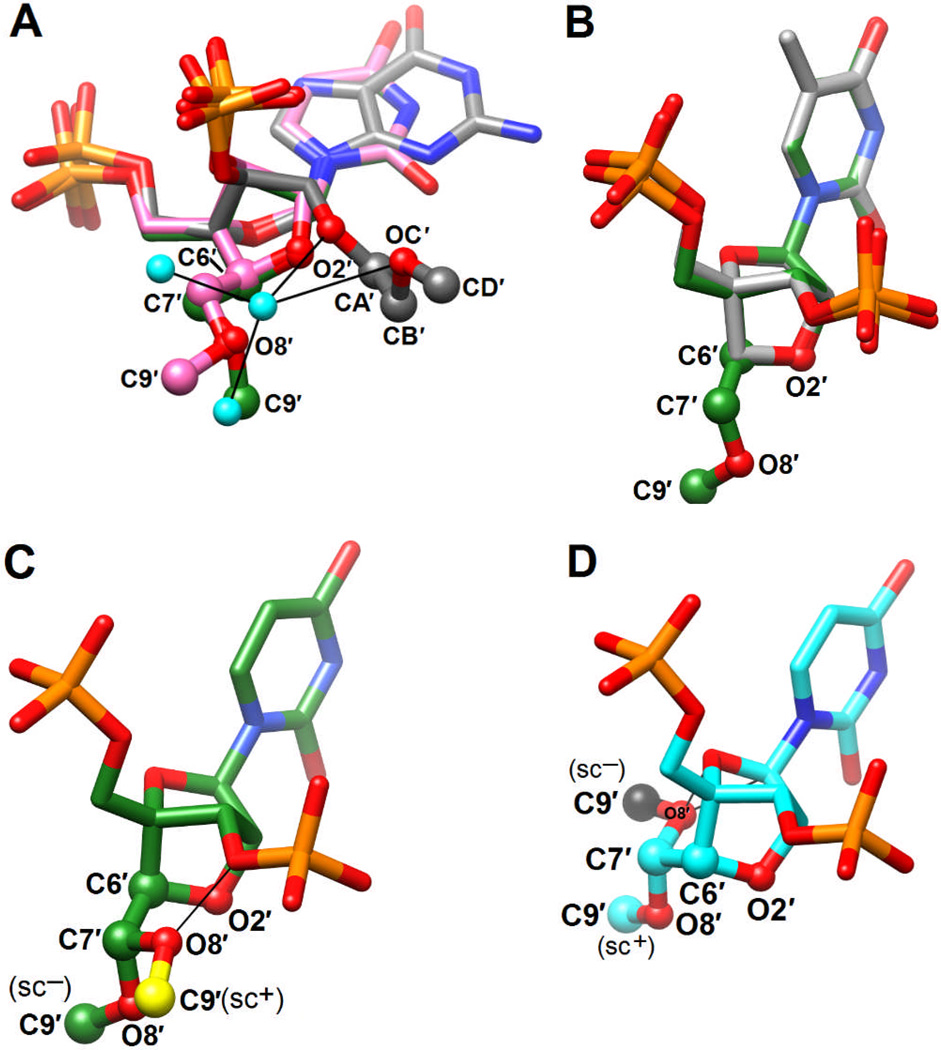

Fig. 2.

The central A5pU*6:A15pU*16 base-pair step viewed into the minor groove of the (A) (R)-cEt BNA, (B) (S)-cEt BNA, and (C) (S)-cMOE BNA duplex crystal structures. Carbon, oxygen, nitrogen and phosphorus atoms are colored in green, red, blue, and orange, respectively, and the O2′-C6′-C7′ cEt and O2′-C6′-C7′-O8′-C9′ cMOE moieties in the modified uridines are highlighted as spheres. Asterisks indicate the stretched ap, ap, ap (α, β, γ) backbone conformation for residues A5.

Superimposition of U*6 and U*16 (S)-cMOE BNA and a 2′-MOE substituted adenosine (PDB ID 469D8) indicates a clear difference between a standard 2′-O-MOE substituent and the cMOE moiety that is part of a bicyclic framework. In the case of 2′-O-MOE, a water molecule is trapped between O3′, O2′ and the MOE oxygen (Fig. 3A, grey carbon atoms and cyan waters), and the substituent is protruding into the minor groove. In the (S)-cMOE BNA structure (Fig. 3A, green/magenta carbon atoms), no water molecules are observed in the immediate vicinity of the substituent and cMOE moieties reside closer to the backbone. Compared to these differences in the orientations of the cMOE and MOE substituents, there is very little deviation between the bicyclic sugar frameworks of cMOE BNA and LNA14 (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

(A) Superimposition of sc− (S)-cMOE BNA U*6 (green cMOE carbons), U*16 (magenta carbons), and an sc− 2′-O-MOE-modified adenosine8 (grey carbons). Apart from the cMOE portion, the conformations of U*6 and U*16 are basically the same and only U*16 atoms are therefore depicted. Atoms of cMOE and MOE moieties are drawn as spheres. Water molecules are cyan and H-bonds are thin solid lines. (B) Superimposition of (S)-cMOE BNA U*6 (green carbons) and LNA-T617 (grey carbons). (C) Comparison between the observed sc− (S)-cMOE BNA conformation (green carbons) and a hypothetical cMOE substituent with an sc+ conformation (yellow C9′), resulting in a short contact by the latter (thin solid line). (D) Comparison between (R)-cMOE BNA residues with the cMOE moiety assuming either the sc− (black C9′) or sc+ (cyan) conformations. Thin solid lines in the case of the former indicate short contacts.

In the (S)-cMOE BNA-modified duplex, the average values for helical rise and twist are 2.8 and 32.3°, respectively. As with the cEt BNA residues in the two other duplexes, the backbone torsion angles for both cMOE BNA residues U*6 and U*16 are in the standard ranges (sc−/ap/sc+/sc+/ap/sc− for α toζ; Fig. 2C). The sugar moieties of all residues except for G19 (C2′-exo) adopt a C3′-endo pucker. Residues G3 and A5 both display the aforementioned, extended backbone conformation.

For both (S)-cMOE BNA uridines, the torsion angle around the central carbon-carbon bond of the MOE moiety (O2′-C6′-C7′-O8′) falls into the sc− range (−53.4°, U*6, and −76.9°, U*16; Fig. 2C, Fig. 3A). A hypothetical model of the cMOE substituent with the torsion angle around the C6′–C7′ bond in the sc+ range gives rise to a steric clash (O8′⋯O3′ = 2.10 Å; Fig. 3C). By comparison, a hypothetical model of the (R)-cMOE BNA analog with the cMOE substituent adopting an sc− conformation exhibits two short contacts: O8′⋯O4′ (2.03 Å) and O8′⋯C1′ (2.22 Å) (Fig. 3D), therefore precluding such a geometry. However, a model of (R)-cMOE BNA with the cMOE substituent in an sc+ conformation appears not to result in any short contacts (Fig. 3D). Although there is a priori no reason to expect a preference for the sc− or the sc+ conformation in MOE-RNA, the crystallographic data showed that the former was twice as common.8

Conclusions

Our structural investigations of cEt and cMOE BNA-modified oligonucleotide duplexes have uncovered particular conformational preferences by the constrained 2′-substituents. Specifically, it appears that the torsion angle around the central C-C bond of (R)- and (S)-cMOE substituents is restricted to the sc+ and sc− ranges, respectively. The corresponding torsion angle in MOE-RNA displays a strong preference for sc compared to ap.8 But the higher RNA affinity of cMOE BNA relative to MOE-RNA is paid for by a further restriction of the 2′-moiety.

Both steric and electrostatic effects can account for the increased nuclease resistance afforded by a modification.15 The 2′,4′-bicyclic framework causes 2′-substituents to lie closer to phosphate groups (Figs. 3A, 4). This tighter spacing and the potential displacement of a catalytically important metal ion in the case of cMOE BNA (Fig. S2) help explain the superior nuclease stability of the BNA modifications studied here relative to MOE-RNA and LNA.

Fig. 4.

Distances between the outermost atom of 2′-substituents and 5′-and 3′-phosphates (drawn with spheres) in (A) MOE-RNA,8 (B) (R)-cEt BNA, and (C) (S)-cEt BNA (this work).

One would likely have expected the small 2′-O-ethyl substituent to provide less protection against nucleases than 2′-O-MOE.15 However, our work demonstrates an improved ability of cEt BNA-modified AONs to dodge degradation compared to AONs with MOE modifications. The structural data provide support for a steric origin of cEt BNA’s high nuclease resistance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by US NIH grant R01 GM55237. Use of the APS was supported by the U. S. Dept. of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Nuclease resistances (Table S1), crystallization experiments, data collection and refinement parameter summary (Table S2), and illustrations of overall structures, quality of the electron density (Fig. S1), and origins of nuclease resistance (Fig. S2). See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Data Deposition: Final coordinates and structure factor files have been deposited in the Brookhaven Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org). The entry codes are 3UKB [(R)-cEt BNA], 3UKC [(S)-cEt BNA], and 3UKE [(S)-cMOE BNA].

Notes and references

- 1.Crooke ST, editor. Antisense Drug Technology: Principles, Strategies, and Applications. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett CF, Swayze EE. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2010;50:259–293. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freier SM, Altmann KH. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4429–4443. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.22.4429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurreck J. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003;270:1628–1644. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swayze EE, Bhat B. In: Antisense Drug Technology: Principles, Strategies, and Applications. 2nd ed. Crooke ST, editor. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2007. pp. 143–182. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin P. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1995;78:486–504. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kastelein JJP, Wedel MK, Baker BF, Su J, Bradley JD, Yu RZ, Chuang E, Graham MJ, Crooke RM. Circulation. 2006;114:1729–1735. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.606442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teplova M, Minasov G, Tereshko V, Inamati GB, Cook PD, Manoharan M, Egli M. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999;6:535–539. doi: 10.1038/9304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seth PP, Siwkowski A, Allerson CR, Vasquez G, Lee S, Prakash TP, Wancewicz EV, Witchell D, Swayze EE. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:10–13. doi: 10.1021/jm801294h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seth PP, Vasquez G, Allerson CA, Berdeja A, Gaus H, Kinberger GA, Prakash TP, Migawa MT, Bhat B, Swayze EE. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:1569–1581. doi: 10.1021/jo902560f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obika S, Nanbu D, Hari Y, Andoh J-I, Morio K-I, Doi T, Imanishi T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:5401–5404. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wengel J. Acc. Chem. Res. 1999;32:301–310. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egli M, Usman N, Rich A. Biochemistry. 1993;32:3221–3237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egli M, Minasov G, Teplova M, Kumar R, Wengel J. Chem. Comm. 2001:651–652. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egli M, Minasov G, Tereshko V, Pallan PS, Teplova M, Inamati GB, Lesnik EA, Owens SR, Ross BS, Prakash TP, Manoharan M. Biochemistry. 2005;44:9045–9057. doi: 10.1021/bi050574m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.