Abstract

We performed a randomized trial to compare nebulized and viscous topical steroid treatments for eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Subjects with incident EoE (n=25) received budesonide 1 mg twice daily—either nebulized and then swallowed (NEB) or as an oral viscous slurry (OVB)—for 8 weeks. Baseline eosinophil counts for the NEB and OVB groups were 101 and 83 (P=.62). Post-treatment counts were 89 and 11 (P=.02). The mucosal medication contact time, measured by scintigraphy, was higher for the OVB group than the NEB group (P<.005) and was inversely correlated with eosinophil count (R= −0.67; P=.001). OVB was more effective than NEB in reducing numbers of esophageal eosinophils in patients with EoE. OVB provided a significantly higher level of esophageal exposure to the therapeutic agent, which correlated with lower eosinophil counts.

Keywords: Clinical trial, Corticosteroid, esophagus, inflammation

Corticosteroids are a mainstay of therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE).1, 2 Rather than using them systemically, they are typically administered as a “topical” preparation; inhaled or nebulized formulations are swallowed to coat the esophagus.1, 2 This approach was first described in retrospective studies of fluticasone and budesonide.3–11 More recently, randomized controlled trials (RCT) have confirmed these agents decrease esophageal eosinophilia.12–14,15, 16,17–19 However, there are few data comparing the efficacy modes of steroids delivery for treatment of EoE, and the esophageal distribution and duration of contact of swallowed topical steroids is not well described.

We conducted an RCT (see Methods, Supplemental Document 1) to compare two methods of topical steroid delivery in EoE. Subjects with incident EoE received budesonide 1 mg twice daily for 8 weeks either nebulized and then swallowed (NEB), or in oral viscous slurry (OVB). Our primary outcomes were eosinophil counts and dysphagia, as measured by Mayo Dysphagia Questionnaire-30 Day (MDQ). We also used nuclear scintigraphy to assess the effect of mucosal medication contact time on eosinophil counts. The median area under the esophageal emptying curve (AUC) was used to estimate esophageal mucosal contact time of the medication. We hypothesized that the steroid delivery method that resulted in the most prolonged mucosal medication contact would result in the best clinical and histological response.

Of the 34 patients screened, 25 met inclusion criteria, and 22 completed the protocol (Supplemental Figure 1). The mean age of the study subjects was 35 years, 60% were male, 88% were Caucasian; all had dysphagia. The baseline characteristics of the two groups were similar (Supplemental Table 1).

After treatment, eosinophil counts markedly improved in the OVB group but not the NEB group (Table 1). At baseline, maximum eosinophil counts for NEB and OVB were 101 and 83 eos/hpf (p=0.62). Post-treatment, the maximum counts were 89 for NEB and 11 for OVB (p=0.02; Supplemental Figure 2). There were similar trends for the histologic cut-point analysis (Table 1). In contrast to the eosinophil counts, dysphagia symptom scores improved in both groups (Table 1; Supplemental Figure 2), and this improvement persisted after excluding patients who received esophageal dilation at baseline. Additionally, improvement in dysphagia did not correlate with endoscopic or histologic improvement (data not shown).

Table 1.

Study outcomes

| NEB (n = 11) |

OVB (n = 11) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcomes | |||

| Overall eosinophil counts (eos/hpf ± SD) | |||

| Baseline maximum eosinophil count | 101 ± 85 | 83 ± 89 | 0.62 |

| Baseline mean eosinophil count | 23 ± 20 | 20 ± 24 | 0.80 |

| Post-treatment max eosinophil count* | 89 ± 94 | 11 ± 23 | 0.02 |

| Post-treatment mean eosinophil count* | 31 ± 37 | 3 ± 7 | 0.02 |

| Maximum eosinophil counts by level (eos/hpf) | |||

| Baseline proximal esophagus | 79 ± 73 | 54 ± 74 | 0.43 |

| Post-treatment proximal esophagus† | 57 ± 78 | 5 ± 17 | 0.04 |

| Baseline mid esophagus | 41 ± 47 | 59 ± 98 | 0.62 |

| Post-treatment mid esophagus‡ | 55 ± 57 | 8 ± 22 | 0.02 |

| Baseline distal esophagus | 54 ± 66 | 53 ± 49 | 0.96 |

| Post-treatment distal esophagus# | 69 ± 81 | 11 ± 23 | 0.03 |

| Symptoms (mean score ± SD) | |||

| Baseline MDQ score | 34 ± 21 | 25 ± 18 | 0.30 |

| Post-treatment MDQ score** | 10 ± 12 | 16 ± 17 | 0.31 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Mucosal medication contact time (median) | |||

| Overall esophageal area under the curve | 19200 | 48900 | 0.005 |

| Proximal esophageal AUC | 7300 | 14400 | 0.14 |

| Mid esophageal AUC | 2800 | 7800 | 0.01 |

| Distal esophageal AUC | 3800 | 18100 | 0.001 |

| AUC with a complete histologic response | 61000 | 65000 | 0.76 |

| AUC without a complete response†† | 19200 | 34000 | 0.06 |

| Histologic response (n, %) | |||

| Complete (< 1 eos/hpf) | 3 (27) | 7 (64) | 0.09 |

| Near-complete (< 7 eos/hpf) | 4 (36) | 8 (73) | 0.09 |

| Partial (< 15 eos/hpf) | 5 (45) | 8 (73) | 0.19 |

| Any response (< baseline eos/hpf) | 6 (55) | 10 (91) | 0.06 |

| Post-treatment EGD findings (n, % with finding) | |||

| Rings | 10 (91) | 4 (36) | 0.008 |

| Narrowing | 6 (55) | 2 (18) | 0.08 |

| Stricture | 3 (27) | 2 (18) | 0.61 |

| Linear furrows | 6 (55) | 4 (36) | 0.39 |

| White plaques/exudates | 3 (27) | 3 (27) | 1.0 |

| Pallor/decreased vascularity | 2 (18) | 0 | 0.14 |

| Crêpe-paper mucosa | 0 | 0 | -- |

| Erosive esophagitis | 0 | 0 | -- |

| Dilation performed | 4 (26) | 3 (27) | 0.65/1.0 |

| EGD improved (n, % global assessment) | 5 (45) | 10 (91) | 0.02 |

| Safety outcomes | |||

| Candidal esophagitis (n, %) | 1 (9) | 2 (18) | 0.53 |

| Baseline adrenal insufficiency (n, %) | 0 | 0 | -- |

| Post-treatment adrenal insufficiency (n, %) | 0 | 0 | -- |

| Post-treatment serum budesonide detected (n, %) | 0 | 0 | -- |

| Esophageal perforation (n, %) | 0 | 0 | -- |

For max eosinophil count comparing baseline to post-treatment, p=0.79 for NEB and p=0.03 for OVB; For mean eosinophil count comparing baseline to post-treatment, p=0.71 for NEB and p=0.03 for OVB

Comparing baseline to post-treatment for the proximal esophagus, p=0.53 for NEB and p=0.03 for OVB

Comparing baseline to post-treatment for the mid esophagus, p=0.39 for NEB and p=0.01 for OVB

Comparing baseline to post-treatment for the distal esophagus, p=0.42 for NEB and p=0.03 for OVB

For MDQ score comparing baseline to post-treatment, p=0.002 for NEB and p=0.04 for OVB

Comparing those with a complete histologic response to those without a complete histologic response, p=0.43 for NEB and p=0.01 for OVB.

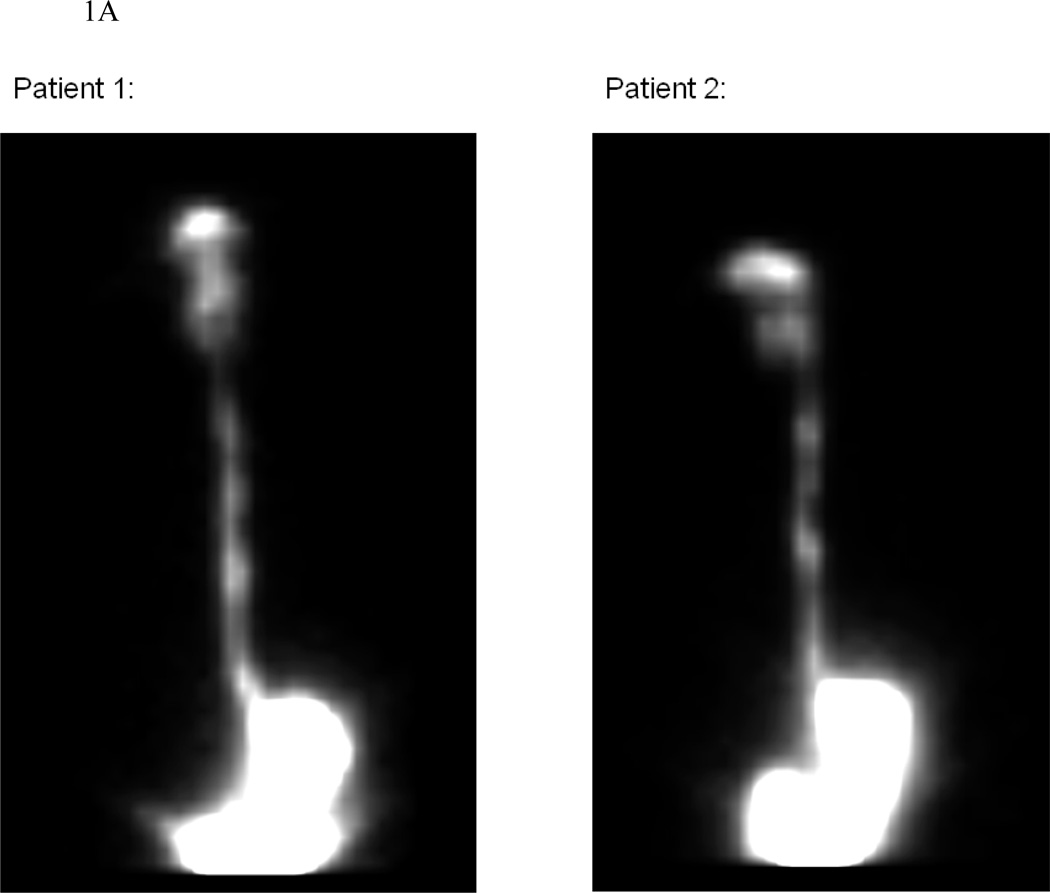

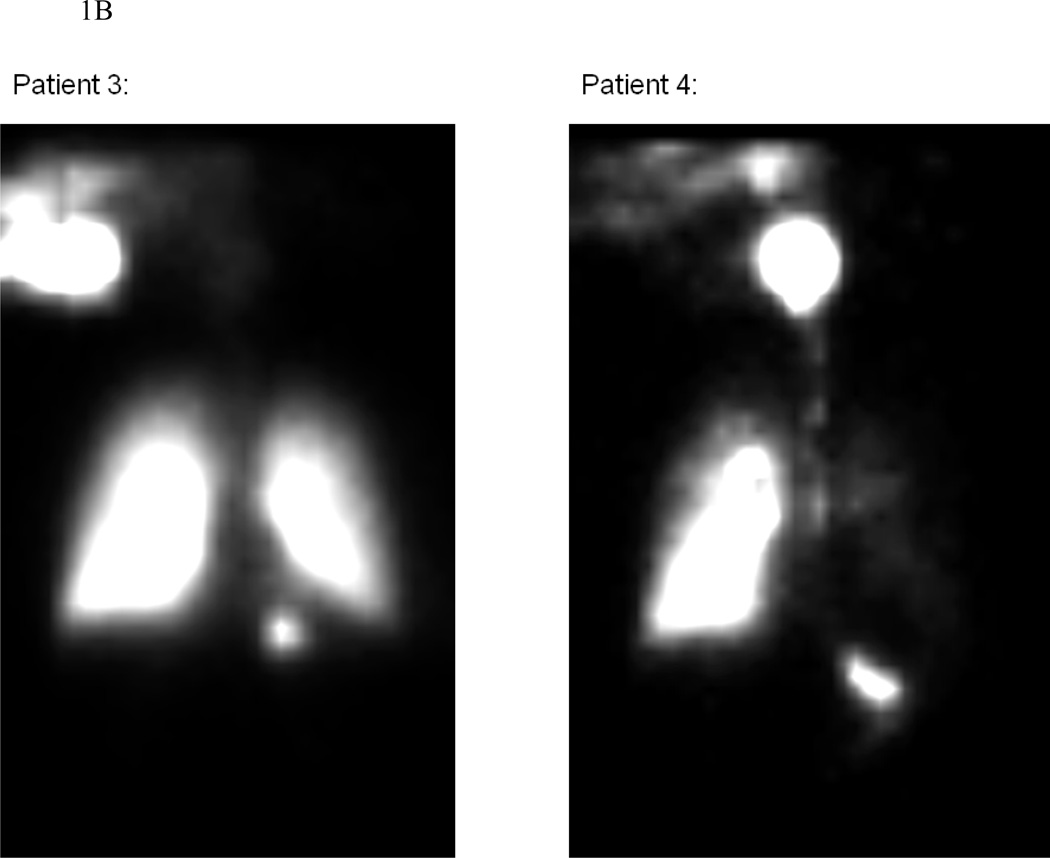

On nuclear scintigraphy, the AUC was higher for OVB than for NEB, suggesting higher mucosal contact time with OVB (Table 1; Figure 1; Supplemental video). Higher mucosal contact time correlated with the decrease in eosinophil count regardless of treatment type (R=−0.67; p=0.001). Similar results were noted when the proximal, middle, and distal esophagus were analyzed individually (Table 1). The AUCs also inversely correlated with the percent change in eosinophil count at each level, with R=−0.44 (p=0.05), R=−0.49 (p=0.05), and R=−0.55 (p=0.009) for the proximal, mid, and distal esophagus. Patients with a complete histologic response tended to have higher mucosal contact times, regardless of treatment type (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Illustrative examples of nuclear scintigraphy esophageal emptying scans for the OVB (panel A) and NEB (panel B) groups. These images represent the total distribution of 99mTc-DTPA tracer throughout the imaging period. Note that for OVB, the medication deposit only in the oropharynx, esophagus and stomach, while for NEB there is also medication deposition in the lungs. In addition, there is qualitatively more deposition in the esophagus and stomach of OVB compared with NEB.

Budesonide was well-tolerated. Three patients (14%) had asymptomatic candidal esophagitis on post-treatment endoscopy (Table 1). One patient in NEB withdrew due to epistaxis. No other local side effects were reported, and no other serious/non-serious adverse events occurred. No patients had adrenal insufficiency by cortisol stimulation testing. No budesonide was detected in the serum after 8 weeks of therapy. No endoscopic complications occurred.

This RCT is the first study comparing two methods of topical steroid delivery for treatment of EoE and the first examining the use of oral viscous budesonide in adults. It also assessed mucosal medication contact time in relation to eosinophil counts, using methodology not previously employed in EoE. We found that OVB was more effective that NEB for decreasing esophageal eosinophil counts, and that increased medication exposure, regardless of the budesonide formulation, was likely the most important determinant of response. The topical, rather than systemic, activity of the medication was further supported by normal post-treatment cortisol stimulation testing and negative serum budesonide levels in all subjects.

Swallowed formulations of topical steroids are popular for the treatment of adults with EoE in the U.S. The use of a viscous solution of budesonide in EoE was first reported by Aceves and colleagues.10, 11 Placebo-controlled RCTs subsequently confirmed the utility of OVB in children,17, 19 and those response rates are similar to the results from the OVB group in the present study. RCT data supporting the use of nebulized/swallowed budesonide in adolescents/adults comes from Straumann and colleagues.18, 20 However, we did not observe the same response in our NEB group. Methodologic differences (length of treatment course; nebulization time) could explain this inconsistency. There have been no prior RCTs comparing different topical steroid agents, and only one case report has addressed this topic.21 It makes intuitive sense that a swallowed formulation, such as OVB, would be easier to administer than a medication from a metered-dose inhaler or a nebulizer. Though the ideal medication delivery system does not yet exist, several are currently under development,19, 22 and possibilities could include gels, powders, or dissolving tablets.

The symptom response in our study, with dysphagia improving in both groups, also warrants mention. Poor correlation between symptoms and histologic/endoscopic findings has been frequently reported.19, 23–27 One reason for this is that no symptom score, including the MDQ, has been validated in EoE.1 In addition, in our study there were more dilations at baseline in the NEB group than in the OVB group. While this could explain improved symptoms despite ongoing inflammation in the NEB group, an analysis excluding those dilated at baseline did not alter the results. Whether to allow baseline dilation will be an important consideration in future EoE studies that use symptoms as primary outcomes.

This study has limitations. Though the study was open label, potential bias was minimized since both arms knew they were receiving an active agent. While there was no placebo group, the placebo response for both OVB and NEB has been well-described and is low.17–19 The sample size was small, but the study was adequately powered for the primary outcomes, and the effect size estimates for the power calculations proved to be accurate. Finally, the study was performed at a single center, so generalizability to other populations is unclear. However, the patients included this study fit the typical characteristics of EoE patients reported from other centers.

Several strengths of our study design deserve mention. The randomized controlled trial design is robust, and the histologic assessment was comprehensive. The mechanistic assessment with nuclear scintigraphy corroborated the main results and introduced new quantitative methodology to this area which may guide future drug development. Finally, the safety evaluation confirmed that both forms of budesonide do not cause adrenal insufficiency after 8 weeks.

In conclusion, this randomized, prospective, open-label, clinical trial showed that orally-administered viscous budesonide was more effective than nebulized/swallowed budesonide for improving esophageal eosinophil counts and endoscopic findings in adults with a new diagnosis of EoE. OVB also yielded significantly higher esophageal medication exposure which correlated with lower eosinophil counts regardless of treatment type, implying that the effect of budesonide is local rather than systemic. Therefore, novel delivery systems to optimize mucosal contact time for topical steroids are needed in EoE.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This research was conducted with support from the Investigator-Sponsored Study Program of AstraZeneca. It was also supported, in part, by NIH awards KL2RR025746 (ESD) and K23DK090073 (ESD), and utilized the Histology Core of the UNC Center for Gastrointestinal Biology and Disease which is funded by NIH P30DK034987, and the UNC Translational Pathology lab which is funded by NIH P30CA016086.

Abbreviations

- AUC

area under the curve

- EGD

esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- EoE

eosinophilic esophagitis

- eos/hpf

eosinophils per high-power field

- MDQ

Mayo Dysphagia Quesionnaire – 30 day

- NEB

nebulized/swallowed budesonide

- OVB

oral viscous/swallowed budesonide

- PPI

proton-pump inhibitor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: There are no potential conflicts of interest for any of the authors pertaining to this study. The funding organizations had no role in the following: design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and drafting of the manuscript. Study is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00961233).

Author contributions (all authors approved this final draft):

Dellon: project conception/design; data acquisition/analysis/interpretation; drafting of the article; critical revision

Sheikh: project conception and design; data acquisition (scintigraphy); data interpretation; and critical revision

Speck: data acquisition (pathology review); and critical revision

Woodward: data acquisition (pathology review); and critical revision

Whitlow: data acquisition (scintigraphy); data interpretation; and critical revision

Hores: data acquisition (clinical); data management; and critical revision

Ivanovic: data acquisition (scintigraphy); data interpretation; and critical revision

Chau: data acquisition (scintigraphy); and critical revision

Woosley: data acquisition (pathology review); and critical revision

Madanick: data acquisition (clinical); and critical revision

Orlando: project conception and design; data interpretation; critical revision

Shaheen: project conception and design; data interpretation; drafting of the article; and critical revision

References

- 1.Liacouras CA, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–20.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furuta GT, et al. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342–1363. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faubion WA, Jr, et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;27:90–93. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199807000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teitelbaum JE, et al. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1216–1225. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arora AS, et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:830–835. doi: 10.4065/78.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noel RJ, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:568–575. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00240-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liacouras CA, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1198–1206. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00885-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Remedios M, et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lucendo AJ, et al. Endoscopy. 2007;39:765–771. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aceves SS, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:705–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aceves SS, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2271–2279. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konikoff MR, et al. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1381–1391. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexander JA, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(Suppl 1):S21. (Ab 58). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaefer ET, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterson KA, et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1313–1319. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0859-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fouad M, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(Suppl 1):S12. (Ab 30). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dohil R, et al. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:418–429. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Straumann A, et al. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1526–1537. 1537 e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta SK, et al. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(Suppl 1):S179. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Straumann A, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:400–409 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krishna SG, et al. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2011;7:55–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neumann D, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(Suppl 1):S8. (Ab 19). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spergel JM, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 (Epub December 27, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Assa'ad AH, et al. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1593–1604. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Straumann A, et al. Gut. 2010;59:21–30. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.178558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pentiuk S, et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:152–160. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31817f0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aceves SS, et al. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;103:401–406. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulz KF, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:726–732. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grudell AB, et al. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:202–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McElhiney J, et al. Dysphagia. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madanick RD, et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonsalves N, et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shah A, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:716–721. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dellon ES, et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1940–1949. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1005-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dorin RI, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:194–204. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-3-200308050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.