Abstract

Background

Alcohol abuse is frequently associated with nicotine use. The current experiments were conducted to establish an oral operant ethanol + nicotine (EtOH + Nic) co-use model, and to characterize some aspects of EtOH + Nic co-use. Methods: Rats were allowed to choose between EtOH alone or EtOH + Nic solutions. Additionally, P rats were allowed to concurrently self-administer 3 distinct EtOH solutions (10, 20, and 30%) with varying amounts of nicotine (0.07, 0.14, or 0.21 mg/ml) under operant conditions. P rats were also allowed to concurrently self-administer 2 distinct amounts of nicotine (0.07 and 0.14 mg/ml) added to saccharin (0.025%) solutions.

Results

During acquisition, P rats responded for the EtOH + Nic solutions at the same level as for EtOH alone, and responding for EtOH + Nic solutions was present throughout all drinking conditions. P rats also readily maintained stable self-administration behaviors for Nic + Sacc solutions. The results demonstrated that P rats readily acquired and maintained stable self-administration behaviors for EtOH + 0.07 and EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic solutions. Self-administration of EtOH+ 0.21 mg/ml Nic was established in only 50% of the subjects. P rats readily expressed seeking behaviors for the EtOH + Nic solutions, and reacquired EtOH + Nic self-administration during relapse testing. In addition, tailblood samples indicated that EtOH + Nic co-use resulted in pharmacologically relevant levels of both EtOH and Nic in the blood.

Discussion

Overall, the results indicate that P rats readily consume EtOH + Nic solutions concurrently in the presence of EtOH alone, express drug-seeking behaviors, and will concurrently consume physiologically relevant levels of both drugs. These results support the idea that this oral operant EtOH + Nic co-use model would be suitable for studying the development of co-abuse and the consequences of long-term chronic co-abuse.

Keywords: Co-use, Co-Abuse, Ethanol, Nicotine, EtOH + Nicotine-seeking, Relapse, Pavlovian Spontaneous Recovery, Alcohol Preferring P rat

INTRODUCTION

In individuals diagnosed with alcohol dependency (AD), the rate of smoking is very high (between 80 and 97%; Hurt et al., 1994; Gulliver et al., 1995; Hughes, 1995, 1996; John et al., 2003a,b), and has remained constant while the overall smoking rate has reduced (John et al., 2003a,b). The severity of nicotine dependency (ND) is linked to more severe levels of relapse (increase in amount of alcohol consumed, duration of high levels of alcohol consumption – benders, and frequency of alcohol use; Abrams et al., 1992; Gulliver et al., 1995) and impair the likelihood that an individual with AD will succeed in becoming abstinent if they continue to smoke during this period (Gulliver et al., 1995; Sobell et al., 1995; Daeppen et al., 2000). In general, humans that co-abuse ethanol (EtOH) and nicotine (Nic) have a worse clinical outcome than individuals who use only one of the drugs (Lajtha and Sershen et al., 2010).

This overwhelming clinical evidence for the prevalence of EtOH + Nic co-abuse/use, supports a need for an animal model of EtOH + Nic co-use that produces chronic, pharmacologically relevant levels of both drugs. In general, pre-clinical studies have provided evidence that Nic effects on EtOH intake are complex. Reports indicated that Nic can increase (Potthoff et al., 1983; Blomqvist et al., 1996; Smith et al., 1999; Olausson et al., 2001; Ericson et al., 2000; Clark et al., 2001; Le et al., 2003; Lallemand et al., 2007), or reduce EtOH intake (Nadal et al., 1998; Dyr et al., 1999; Sharpe and Samson, 2002). Interestingly, the majority of the Nic experiments that see an enhancement in EtOH intake administer Nic repeatedly to the animals, whereas the reductions seem to occur when Nic is given acutely (see review Le, 2002).

There have been only a few studies to examine the effects of Nic on EtOH seeking and relapse. Nic can enhance relapse behaviors such as EtOH-seeking (Le et al., 2003; Hauser et al., 2012) and EtOH relapse drinking (Lopez-Moreno et al., 2004; Alen et al., 2009; Hauser et al., 2012). One limitation to these previous studies is that Nic was always given by the experimenter. Utilizing co-use models where the animals can chronically self-administer both EtOH and Nic may provide us with useful information of how interaction between EtOH and Nic can produce neuronal alterations and promote the development of co-abuse.

Past studies have attempted to establish oral nicotine consumption in rats, but the success of these endeavors has been limited by a number of factors. Fluid deprived rats will self-administer oral Nic (0.06 mg/ml) under operant conditions that are reduced by injections of mecamylamine (Glick et al., 1996). Under 24 hour free-choice conditions (multiple Nic concentration solutions available), Sprague-Dawley rats given access to 0.006% Nic solutions consumed on average 0.0375 mg/kg/hour (Maehler et al., 2000). Under comparable conditions in NIH stock rats, oral nicotine consumption was highly variable between rats and within rats between days, with an average Nic consumption being approximately 0.06 mg/kg/hour (Dadmarz and Vogel, 2003). Additional experiments using very low levels of Nic solutions (0.003, 0.005 or 0.008 mg/ml) resulted in average Nic consumption of approximately 0.0125 mg/kg/hour (Biondolillo and Pearce, 2007; Biondolillo et al., 2009). The concentration of Nic employed in these studies would be undetectable in rats (Flynn et al., 1989).

Recently, corporations have successfully introduced nicotine laced water (Nico Water®), nicotine infused fruit drink (Platinum Products), beer brewed with tobacco (NicoShot®), and a 15% nicotine energy drink (Liquid Smoking®). Last year, RJ Reynolds test marketed numerous oral nicotine products (Camel Orbs® and Camel Strips®) with such positive returns that other major tobacco firms are beginning to test market similar products (US SEC perspective postings). Therefore, studies on the effects of oral consumption of nicotine have an immediate need.

Although the previous oral Nic studies resulted in lower levels of Nic within a hour, they demonstrated that multiple presentations of Nic can produce stable and high intakes of Nic in non-selected rats (Maehler et al., 2000; Dadmarz and Vogel, 2003; Biondolillo and Pearce, 2007; Biondolillo et al., 2009). In addition, the presentation of multiple concentrations of EtOH, under-24 hour free choice drinking conditions, can increase the baseline levels EtOH intake in alcohol preferring rats (P, HAD) as well as non-preferring rats (NP, LAD, Wistar) (Rodd-Henricks et al. 2001; Rodd et al., 2009; Bell et al., 2004; Holter et al., 1998; Wolffgramm and Heyne, 1995). Taken together, these studies suggest that the use of the multiple presentation method may allow the experimenter to achieve higher EtOH and Nic intakes in their animal models. Therefore, in the current study, multiple concentrations of EtOH + Nic or Nic + Saccharin (Sacc) were presented under operant conditions to achieve levels of EtOH and Nic intake that would produce pharmacologically relevant levels of both drugs.

The selectively bred alcohol preferring (P) rat has been well characterized both behaviorally and neurobiologically (McBride and Li, 1998; Murphy et al., 2002) and satisfies criteria proposed as essential for an animal model of alcoholism (Lester and Freed, 1973; Cicero, 1979). Studies have demonstrated that P rats are more likely to substitute Nic for EtOH (McMillan et al., 1999) and express greater drug elicited (Nic primed) Nic-seeking (Le et al., 2006). Moreover, they are less sensitive to the CNS depressive effects of high levels of Nic than the non-preferring rats (NP) (Katner et al., 1996). Nic also has greater reinforcing effects in P rats than NP rats (Le at al., 2006), which supports the hypothesis that vulnerability to EtOH and Nic addiction may share common genetic traits.

The objectives of the current study were to determine: 1) if P rats would self-administer EtOH + Nic solutions when concurrently given only EtOH, 2) the effects of co- administration EtOH + Nic on drug-seeking and relapse behaviors, and 3) if P rats would self-administer Nic + Sacc solutions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Adult female P rats from the 64th generation weighing 250–325g at the start of the experiment were used. Rats were maintained on a 12-hour reversed light-dark cycle (lights off at 0900 hour). Food and water were available ad libitum throughout the experiment, except during operant testing. The animals used in these experiments were maintained in facilities fully accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). All research protocols were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee and are in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Care and Use Committee of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council, 1996).

Chemical Agents and Vehicle

Ethyl alcohol (190 proof; McCormick Distilling Co., Weston, MO) was diluted to 10%, 20%, and 30% with distilled water for operant oral EtOH self-administration sessions. Saccharin (Sacc) was dissolved with distilled water for operant oral Sacc self-administration sessions. Nic hydrogen tartrate salt was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Nic concentrations of 0.07, or 0.14, or 0.21 mg/ml were dissolved in the 10%, 20%, and 30% EtOH concentrations for operant oral EtOH + Nic self-administration sessions. Nic concentrations of 0.07 or 0.14 mg/ml were dissolved in the 0.025% Sacc solution for operant oral Nic + Sacc self-administration sessions. All Nic doses refer to the salt form.

Operant Apparatus

EtOH + Nic self-administration procedures were conducted in 3-lever experimental chambers (Coulbourn Instruments, Whitehall, PA) contained within ventilated, sound-attenuated enclosures. Three operant levers, located on the same wall, were 15 cm above a grid floor and 13 cm apart. A trough was directly beneath each lever, from which a dipper cup could raise to present fluid. Upon a reinforced response on the respective lever, a small cue light was illuminated in the drinking trough and 4 seconds of dipper cup (0.1 ml) access was presented. A personal computer controlled all operant chamber functions while recording lever responses and dipper presentations. On the opposite wall, water was available through a non-contingent spout connected to a water bottle that was placed outside of the chamber.

For the Nic + Sacc self-administration, procedures were conducted in standard two-lever experimental chambers (Coulbourn Instruments, Whitehall, PA) contained within ventilated, sound-attenuated enclosures. The design and protocol for the two-lever operant boxes are the same, except a separate water bottle was not available.

Operant Training

P rats were placed into the operant chamber without prior training. Operant sessions were 60 minute in duration and occurred daily (7 days each week) for 10 weeks (Rodd et al., 2006). All levers were maintained on an FR1 schedule of reinforcement for 4 weeks. At the end of this time, the response requirement for EtOH + Nic was increased to an FR-3 schedule for 3 weeks, and then to an FR-5 schedule for 3 weeks.

Rats were divided into two groups (Nic + Sacc or Sacc alone) for the Nic self-administration experiment. For the Nic + Sacc group, P rats (n=6–7/group) were placed into the operant chamber and allowed to self-train. The Nic + Sacc concentrations used for operant administration were 0.07 mg/ml Nic + 0.025% (g/vol) Sacc, and 0.14 mg/ml Nic + 0.025% Sacc (g/vol). For the Sacc alone group, the concentration used for operant administration was 0.025% (g/vol), and this concentration was available on both levers.

Experiment 1: Concurrent Access to EtOH alone and EtOH +Nic Solutions during Acquisition, Maintenance, and Relapse

Experimentally naïve rats were given concurrent access to 15% EtOH alone, 15% EtOH + 0.07 mg/ml Nic, and 15% EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic concentrations. Following 10 weeks of consecutive operant sessions, all rats were housed in the home cages for 14 days. Rats were then transferred to the operant chambers with EtOH and EtOH + Nic solutions for the 60 minute sessions to test relapse drinking. All levers were maintained on an FR5 schedule for relapse testing.

Experiment 2: Access to Multiple EtOH + Nic Concentrations During Acquisition, Maintenance, Seeking, and Relapse

Experimentally naïve rats received access to multiple EtOH concentrations (10, 20, and 30%). All concentrations of EtOH were combined with either 0.07 (n = 8), 0.14 (n = 16), or 0.21 (n = 8) mg/ml Nic. For example, a rat would be given concurrent access to 10% EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic, 20% EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic, and 30% EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml. Following 10 weeks of consecutive operant sessions, rats were exposed to 10 sessions of extinction training (no fluid available). After extinction training, all rats were restricted to the home cages for 14 days. Next, rats were tested for drug-seeking using the Pavlovian Spontaneous Recovery (PSR) paradigm (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2002a, b). During PSR testing, lever contingencies and dipper functioning remained the same but EtOH and water were absent. After the PSR phase of the experiment, all rats were again maintained in the home cages for 14 days. Rats were then transferred to the operant chambers with the EtOH + Nic solutions present for the 60 minute sessions to test for relapse drinking.

Experiment 3: Concurrent Access to Nic +Sacc Solutions or Sacc Alone During Acquisition and Maintenance

Experimentally naïve rats were divided into two groups. The Sacc (n = 7) alone group was given access 0.025% Sacc on both levers. The Nic + Sacc group (n = 6) was given concurrent access to 0.07 mg/ml Nic + 0.025% Sacc and 0.14 mg/ml Nic + 0.025% Sacc solutions. Rats were trained for 10 weeks of consecutive operant sessions.

Determining the Blood Levels of Nic and EtOH in P rats Self-Administering EtOH + Nic Solutions

Subjects were allowed to self-administer the EtOH + Nic solutions for 2 additional weeks following the deprivation period. Following the 15th post-deprivation self-administration session, tail-bloods were immediately obtained for P rats self-administering EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic. One week later, brains and trunk blood were collected 3 hours after the operant session in P rats self-administering EtOH + 0.07 mg/ml Nic. For the Nic + Sacc group tail bloods were immediately obtained from rats concurrently self-administering 0.07 mg/ml Nic +Sacc and 0.14 mg/ml Nic + Sacc on 3rd day during the 10th week of operant responding.

Samples were analyzed for concentration of EtOH using a standard Analox® protocol. The blood levels of Nic and cotinine (active metabolite of nicotine) were assessed through use of an HPLC analysis technique based upon modifications of a previously published procedure (Page-Sharp et al., 2003).

Statistical Analyses

Overall operant responding (60 minute) data were analyzed with a mixed factorial ANOVA with a between subject factor of dose and a repeated measure of ‘session’. For the relapse studies, the baseline measure for the factor of ‘session’ was the average number of responses on the EtOH + Nic or EtOH lever for the 3 sessions immediately prior to extinction. Post-hoc Tukey’s b tests were performed to determine individual differences. For the PSR experiments, the baseline measure for the factor of ‘session’ was the average number of responses on the EtOH + Nic lever for the last 3 extinction sessions. Post-hoc Tukey’s b tests were performed to determine individual differences. Pairwise t-tests were used to compare PSR session to extinction baseline.

RESULTS

Experiment 1: Concurrent access to EtOH alone and EtOH + Nic Solutions during Acquisition and Maintenance

P rats given concurrent access to 15% EtOH, 15% EtOH + 0.07 mg/ml Nic and 15% EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic responded for all 3 solutions during acquisition (Fig. 1A). A repeated measure ANOVA indicated an effect of session (p < 0.01), but no effect of Lever (p = 0.14) or a Lever x session interaction (p = 0.55). Post-hocs (Tukey’s) revealed that there were no significant differences in acquiring EtOH alone or the EtOH + Nic solutions for P rats (p > 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Lever responses for concurrent access to 15% EtOH, 15% EtOH + 0.07 mg/ml Nic and 15% EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic (n = 8) during acquisition and maintenance. Fig. 1A: Comparisons of mean (± S.E.M.) responses per session (FR5 schedule) by P rats with concurrent access to EtOH alone and EtOH + Nic solutions during acquisition. There were no significant differences in acquisition between the EtOH alone and EtOH + Nic solutions. Fig. 1B: Comparisons of mean (± S.E.M.) responses per session (FR5 schedule) by P rats with concurrent access to EtOH alone and EtOH + Nic solutions during maintenance. Asterisk (*) indicates that P rats responded significantly more on the EtOH alone lever during sessions 1–2 and 5–6 compared to either EtOH + Nic lever (p < 0.031).

Examining the number of responses on the lever associated with the delivery of EtOH and the EtOH + Nic solutions (Fig. 1B) indicated there was no significant effect of session (F6, 16 = 1.33; p = 0.301) or a significant session by lever interaction (F12, 34 = 0.859; p = 0.059). However, there was a significant lever effect (F 2, 21 = 4.86; p = 0.018). An ANOVA was performed for responding on the three levers for each session. The responses were significantly higher on the EtOH alone lever during sessions 1–2 and 5–6 compared to both EtOH + Nic levers (p values < 0.031). Although there was a preference for the EtOH alone solution, P rats responded more than 100 times combined per session for both EtOH + Nic solutions, and still maintained a high level of Nic intake. The combined responding for the two EtOH + Nic solutions approximated the responding for the EtOH alone solutions (i.e., sessions >, 100 responses for EtOH + Nic vs 125 responses for EtOH alone). The analysis of the number of reinforcers (Table 1) for the 15% EtOH and 15% EtOH + Nic levers indicated that there was no significant effect of session (F6,9= 1.26; p = 0.36), group (F1,14= 1.28; p = 0.28), or interaction term ‘session x group’ (F6,9 = 0.90; p = 0.53). The estimated EtOH intake was 1.5 g/kg/session and the estimated Nic intake was 1.0 mg/kg/session over the last 7 days of maintenance for rats that had concurrent access to EtOH alone and EtOH + Nic.

Table 1.

Mean (± S.E.M.) for total reinforcers per session on a FR5 schedule during maintenance. There were no other significant group differences between 15% EtOH alone and 15% EtOH + Nic (p > 0.05).

| Maintenance Reinforcers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solutions | Sessions: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Experiment 1 | 15% EtOH | 25±6 | 35±12 | 26±6 | 26±9 | 32±9 | 32±8 | 28±6 | |

| 15% EtOH + NIC (total) | 14±5 | 14 ± 3 | 21±5 | 22±5 | 16±4 | 24±5 | 24±8 | ||

|

|

|||||||||

| Experiment 2 | EtOH + 0.07 Nic mg/ml (total) | 26±5 | 31±7† | 36±8 | 25±5 | 25±6 | 21±7† | 30±7† | |

| EtOH + 0.14 Nic mg/ml (total) | 44±5* | 42±4† | 43±5 | 41±3* | 45±5* | 43±4† | 39±4† | ||

| EtOH + 0.21 Nic mg/ml (total) | 13±7 | 20±7 | 20±10 | 21±8 | 17±7 | 16±6 | 18±7 | ||

|

|

|||||||||

| Experiment 3 | 0.025% Sacc (total) | 107±35 | 110±27# | 129±38 | 134±34 | 119±31# | 142±49 | 139±40 | |

| Nic + 0.025% (total) | 26±5 | 32±6 | 50±5 | 52±7 | 39±8 | 52±9 | 59±14 | ||

Asterisk (*) indicates that total reinforcers per session for EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic was significantly higher compared to EtOH + 0.07 mg/ml Nic and EtOH + 0.21 mg/ml Nic (p ≤ 0.05). Dagger (†) indicates that total reinforcers per session for EtOH + 0.07 mg/ml Nic and EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic was significantly higher compared to EtOH + 0.21 mg/ml Nic (p ≤ 0.05). Pound (#) indicates that total reinforcers per session for Sacc alone was significantly higher compared to Nic + Sacc.

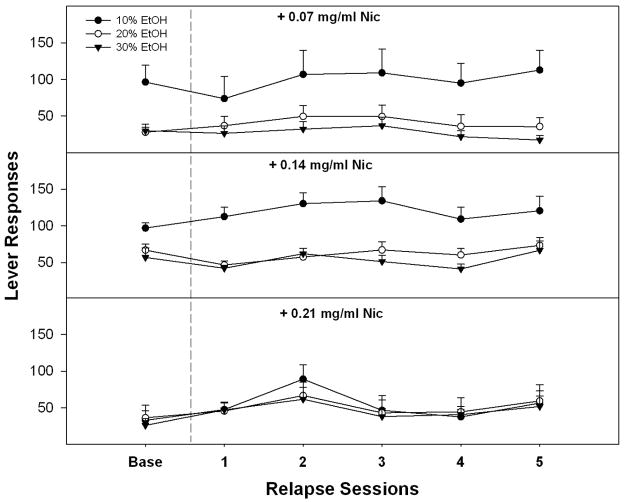

Experiment 2: Self-administration of 10, 20, 30 % EtOH Containing Nic during Maintenance, PSR and Relapse

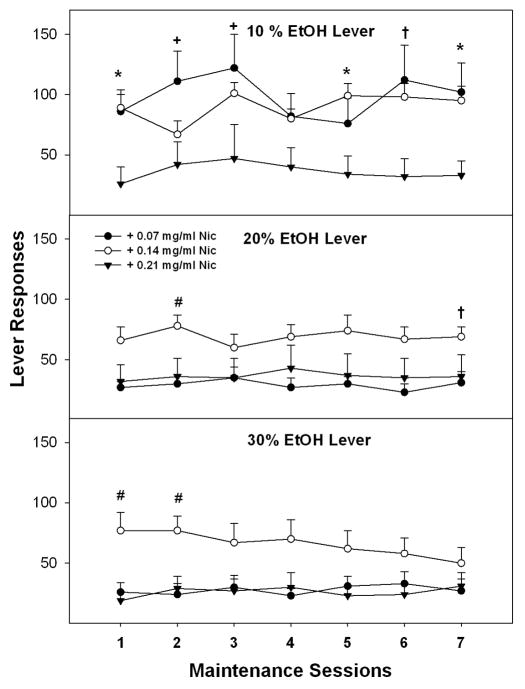

A repeated measure ANOVA was performed on the number of lever responses during the last 7 sessions prior to extinction training (Fig. 2). The overall analysis indicated a significant effect of EtOH concentration (F2, 28 = 7.97; p = 0.002), Nic concentration (F2, 29 = 7.4; p = 0.003) and an interaction term (F4, 58 = 5.5; p < 0.001). The lack of an effect of session indicated that responding was consistent within each group. Collapsing across the sessions, decomposing the significant interaction term revealed that there was a significant effect of Nic concentration for responding for 10% (F2, 29 = 6.85; p = 0.004) and 20% EtOH (F2, 29 = 4.1; p = 0.028), but not 30% EtOH (F2, 29 = 2.4; p = 0.11). Post-hoc comparisons (Tukey’s b) indicated that P rats responded more for 10% EtOH + 0.07 and 10% EtOH + 0.14 mg/kg Nic than 10% EtOH + 0.21 mg/ml. In addition, P rats responded more for 20% EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic than all other Nic concentrations during maintenance. Individual ANOVAs were performed for responding on the three levers for each session. The responses for 10% EtOH lever were significantly higher for 0.07 mg/ml Nic concentration during sessions 1–3, 5 and 7 and for 0.14 mg/ml Nic concentrations during sessions 1, 5–7 compared to 0.21 mg/ml Nic (p values ≤ 0.046; p values ≤ 0.011 ). The responses for 20% EtOH lever were significantly higher for 0.14 mg/ml Nic concentration during sessions 2 and 7 compared to 0.07 mg/ml Nic, and during session 2 compared to 0.21 mg/ml Nic (p values ≤ 0.03). The responses for 30% EtOH lever were significantly higher for the 0.14 mg/ml Nic concentration during sessions 1–2 compared to 0.07 mg/ml and 0.21 mg/ml Nic (p values ≤ 0.01).

Fig. 2.

Lever responses on an (FR5) schedule of reinforcement for EtOH + Nic solutions during maintenance self-administration for week 10. Mean (± S.E.M.) responses per session on the lever for delivery of 10%, 20% and 30% EtOH containing 0.07, 0.14 or 0.21 mg/ml Nic (n = 8–16/dose/group). Asterisk (*) indicates that P rats responded significantly more for 10% EtOH + 0.07 and 10% EtOH + 0.14 mg/kg Nic than 10% EtOH + 0.21 mg/ml Nic. Pound (#) indicates P rats responded more for 20% EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic or 30% EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic than the other Nic concentrations. Plus (+) indicates that P rats responded significantly more for 10% EtOH + 0.07 than 10% EtOH + 0.21 mg/ml Nic. Dagger (†) indicates that P rats responded more for 10% EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic than 10% EtOH + 0.21 mg/ml and responded more for 20% EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic than 20% EtOH + 0.07 mg/ml Nic.

For the EtOH +Nic groups, analysis of the number of reinforcers (Table 1) indicated there was no significant effect of session (F6, 24 = 0.64; p > 0.70) but there was significant effect of group (F2, 29 = 7.35; p < 0.01). There was no significant interaction term ‘session x group’ (F12,80 = 1.17; p > 0.3). Post-hoc comparisons (Tukey’s b) indicated that P rats received more reinforcers for EtOH + 0.07 mg/ml Nic and EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic compared to EtOH + 0.21 mg/ml Nic (p > 0.05). Individual ANOVAs revealed that P rats obtained more reinforcers for EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic than EtOH + 0.07 mg/ml Nic and/or EtOH + 0.21 mg/ml Nic during most sessions (p ≤ 0.03, Table 1).

Estimated EtOH and Nic intakes in the EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic group were 2 g/kg EtOH and 2 mg/kg Nic (0.72 mg/kg/base) compared to the EtOH + 0.07 mg/ml group (1.1 g/kg EtOH and 0.7 mg/kg Nic [0.25 mg/kg/ base]) or EtOH + 0.21 mg/ml Nic group (0.9 g/kg EtOH and 1.3 mg/kg Nic [0.47 mg/kg/base]).

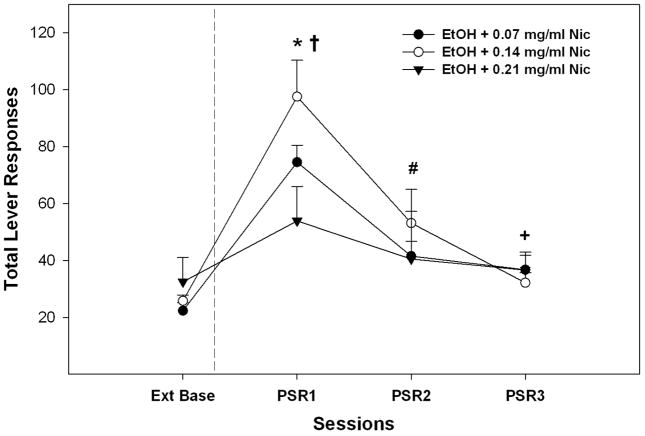

An analysis on the EtOH lever responses during the PSR test sessions that collapsed data for all 3 EtOH concentrations (Fig. 3) indicated there was a significant session x Nic interaction (F6, 56 = 3.9; p = 0.018) between the extinction baseline and PSR sessions 1–3. Individual ANOVAs indicate a significant Nic group effect during the 1st PSR session (p = 0.043), but not for the extinction baseline or PSR sessions 2 or 3 (p values > 0.45). Post-hoc comparisons indicated that P rats with a history of self-administering EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic expressed higher responding than P rats with a history of self-administering EtOH + 0.21 mg/ml Nic. Contrasting lever responses during PSR test sessions with extinction baseline (pairwise t-tests) indicated that all EtOH + Nic groups responded more during the 1st PSR test session compared to extinction baseline (p values < 0.006). A higher level of responding was still observed during the 2nd (both 0.07 and 0.14 mg/ml Nic groups) and 3rd (0.14 mg/ml Nic group; 24 ± 3 vs 37 ± 5) PSR test sessions compared to extinction. For relapse EtOH + Nic drinking, a repeated measure ANOVA consisting of within subject factors of session and EtOH concentration and a between subject factor of Nic concentration revealed a significant interaction (F4, 58 = 2.68; p = 0.04). The lack of an effect of session indicated that oral operant self-administration of EtOH + Nic was not significantly altered following a period of deprivation (Fig. 4). This significant interaction term was based upon the factors identified during the maintenance period (10% EtOH + Nic responding higher in 0.07 and 0.14 mg/ml groups compared to 0.21 group; p ≤ 0.02).

Fig. 3.

Total mean (± S.E.M.) responses per session during PSR testing on the lever previously associated with the delivery of EtOH + Nic (n = 8–16/dose/group). Asterisk (*) indicates that all EtOH + Nic groups responded significantly (p < 0.05) more on the EtOH + Nic lever during the first PSR session compared to extinction baseline levels. Pound (#) indicates that EtOH + 0.07mg/ml Nic and EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic groups responded significantly (p < 0.05) more on the EtOH+NIC lever during the second PSR session compared to extinction baseline levels. Plus (+) indicates that EtOH + 0.07 mg/ml Nic responded significantly (p < 0.05) more on the EtOH + Nic lever during the third PSR session compared to extinction baseline levels. Dagger (†) indicates that P rats with a history of self-administering EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic expressed higher responding than P rats with a history of self-administering EtOH + 0.21 mg/ml Nic.

Fig. 4.

Mean (±S.E.M.) responses per session (FR5 schedule) during relapse testing on the lever associated with the delivery of 10%, 20% and 30% EtOH containing 0.07, 0.14 or 0.21 mg/ml Nic (n = 8–16/dose/group). There were no significant differences between baseline and relapse responding (p > 0.05).

The estimated baseline for EtOH intake prior to relapse testing for rats that had access to EtOH containing 0.07 mg/ml, 0.14 mg/ml, or 0.21 mg/ml Nic was approximately 1.2, 1.9, and 0.9 g/kg in the 60-minute sessions, respectively. These values were not significantly altered during relapse. The estimated baseline for Nic intake prior to relapse testing for rats that had access to EtOH containing 0.07 mg/ml, 0.14 mg/ml, or 0.21 mg/ml Nic was approximately 0.7 (0.25 mg/kg/base), 2.1 (0.76 mg/kg/base), and 1.3 (0.47 mg/kg/base) mg/kg in 60 minute sessions, respectively.

Blood Levels of Nic and EtOH in P rats Self-Administering EtOH + Nic Solutions

In P rats self-administering EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic, the analysis of the tail blood samples indicated that the average BEC was 78 ± 5 mg%, while concurrently the blood nicotine level was 56 ± 4 ng/ml and cotinine level was 34 ± 4 ng/ml. Trunk blood samples taken 3 hour after the operant session from P rats responding for EtOH + 0.07 mg/ml Nic revealed levels of Nic (7.8 ± 0.9 ng/ml) and cotinine (41.3 ± 4.5 ng/ml) and a reduced BEC (11 ± 1.2 mg%).

Experiment 3: Self-administration of Nic + Sacc and Sacc alone during Acquisition and Maintenance

Figure 5A shows the total lever response for acquisition during the first 13 days of exposure to the group given combined Nic + Sacc solution and the group given Sacc alone. Individual ANOVAs performed on the total lever responses in each session indicated that during sessions 8–13, there was significant group effect (F1, 11 values > 12.28; p values ≤ 0.011). Post-hocs tests (Tukey’s) revealed that P rats self-administering Sacc alone had more total lever responses than P rats self-administering Nic + Sacc. There were no group differences during sessions 1–7. In P rats self-administering Nic + Sacc, there was an increase in responding from session 9 onward compared to sessions 1 and 2, whereas in P rats self-administering Sacc alone this increase was observed from session 6 onward (p values < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Lever responses for Nic+ Sacc (0.025% g/vol) or Sacc (0.025% g/vol) alone during acquisition and maintenance. Fig. 5A: Mean (± S.E.M.) responses per session on the lever associated with the delivery of 0.025 % Sacc containing 0.07 or 0.14 mg/ml Nic, or Sacc alone (n = 6–7/group). Asterisk (*) indicates that responding for Nic + Sacc increased from session 9 onward and Sacc alone lever responses also increased from session 6 onward. Fig. 5B: Lever responses for Nic + Sacc or Sacc alone during maintenance in week 10. Mean (± S.E.M.) responses per session on the lever associated with the delivery of 0.025% Sacc containing 0.07 or 0.14 mg/ml Nic, or Sacc alone (n = 6–7/group).

A repeated measure ANOVA was performed on the number of lever responses during the last 7 sessions (Fig. 5B). The overall analysis indicated a significant effect of session (F6, 11 = 6.18; p = 0.005), and group (F1, 11 = 8.49; p = 0.05), but there was no significant ‘session x group’ interaction (F12, 24 = 0.796; p > 0.6). Post-hoc comparisons (Tukey’s b) indicated that P rats responded similar for 0.07 mg/ml Nic + Sacc and 0.14 mg/ml Nic + Sacc solutions. Even though there were no significant difference between 0.07 mg/ml Nic + Sacc and 0.14 mg/ml Nic + Sacc solutions, the rats responded 2 times more on 0.07 mg/ml Nic + Sacc than the 0.14 mg/ml Nic + Sacc lever. P rats responded more for Sacc alone than Nic + Sacc concentrations during maintenance (p values < 0.01).

In P rats concurrently self-administering 0.07 mg/ml Nic + Sacc and 0.14 mg/ml Nic + Sacc their combined levers responding for Nic + Sacc solutions resulted in estimated Nic intakes of 1.3 mg/kg (0.46 mg/kg/base). The analysis of the tail blood samples indicated that the average Nic level was 21 ± 6 ng/ml and cotinine level was 208 ± 43 ng/ml.

For the Nic + Sacc and Sacc alone groups analysis of the number of reinforcers indicated a significant effect of sessions (F6,6 = 9.33; p < 0.01) and group (F1, 11 = 8.42; p = 0.05), but there was no significant interaction term ‘session x group’ (F6,6 = 0.33; p > 0.89). Individual ANOVAs revealed that P rats significantly obtained more reinforcers for Sacc alone than Nic + Sacc during sessions 2 and 5 (p ≤ 0.04, Table 1), whereas there was trend toward significant differences for sessions 1, 3, 4, 6, and 7 (p ≥ 0.06, Table 1).

DISCUSSION

The major findings of this study demonstrate that P rats will readily acquire, maintain, and reacquire self-administration of EtOH + Nic solutions under a three lever operant paradigm. More importantly, P rats will readily self-administer EtOH + Nic solutions to attain pharmacologically relevant levels of both drugs. In addition, P rats will display drug-seeking behaviors for EtOH + Nic solutions that can be prolonged for three days depending on the concentration of Nic.

In the first experiment, the P rats were given a choice between EtOH (15%) alone and 2 different EtOH (15%) + Nic (0.07 or 0.14 mg/ml) solutions in the same operant sessions to determine if P rats will self-administer EtOH + Nic solution in the presence of EtOH alone. The rats acquired responding for EtOH alone and the EtOH + Nic solutions at a similar rate (Fig. 1A). During maintenance, higher responding for EtOH alone was observed compared to responses for the individual EtOH + Nic solutions (Fig. 1B). However, comparisons of the total numbers of reinforcers obtained for the combined EtOH + Nic solutions compared to EtOH alone indicated there were no significant differences (Table 1). The estimated mean EtOH intake was 1.5 g/kg with an average Nic intake of 1 mg/kg (0.36 mg/kg/ base) over the last 7 sessions of maintenance. Progressive ratio testing revealed that P rats had similar break points (~FR 20) for 15% EtOH alone, 15% EtOH+ 0.07 mg/ml Nic, and 15% EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic (data not shown) indicating that P rats will increase the amount of work to obtain either EtOH alone or EtOH+ Nic. However, the results also indicate that addition of Nic to the EtOH solution does not increase the reinforcement value of the solution. Collectively, these findings indicated that P rats will voluntarily choose to consume EtOH + Nic when the option of EtOH alone is available.

Recently, Le et al. (2010) demonstrated the choice for oral EtOH and i.v. Nic in an operant paradigm resulted in estimated average EtOH intakes of 1 g/kg and Nic intakes of ~1 mg/kg/base in 60 minute session. In addition, EtOH self-administration tended to decrease Nic self-administration (Le et al., 2010). There were no assessments of blood EtOH, Nic, or cotinine levels in the Le et al. (2010) report. In general, to establish i.v. nicotine self-administration in rats, there are numerous requirements (e.g., weight reduction, prior nicotine exposure) to overcome the possible aversive properties through this route of administration (c.f. Palmatier et al, 2008). The oral EtOH and i.v. Nic co-administration procedure may be technically too difficult for most labs to use. The i.v. procedure may limit the viability of mass testing (loss of patency of i.v. catheters prevents testing of chronic nicotine exposure) and adds potential confounds (food restrictions and the caloric value of EtOH). The oral EtOH +Nic procedures do not require surgical procedures to establish co-use and can be used for prolonged periods to study the consequences of chronic co-use.

One the major goals of the current study was to establish a co-use model where P rats would self-administer high EtOH and Nic intakes that produce pharmacologically relevant levels of both drugs. In the second experiment, P rats were allowed to concurrently self-administer 3 distinct EtOH solutions (10, 20, and 30%) with varying amounts of nicotine (0.07, 0.14, or 0.21 mg/ml) under operant conditions. P rats readily maintained self-administration for EtOH solutions containing 0.07 mg/ml (0.025 mg/ml/ base) and 0.14 mg/ml Nic (0.05 mg/ml /base) (Fig. 2). However, EtOH solutions mixed with the highest Nic concentration (0.21 mg/ml [ 0.076 mg/ml/base]) were acquired at a much slower rate and only 50% of the P rats maintained stable self-administration of the high-EtOH + Nic solution. Fig. 2 shows data for P rats that acquired reliable operant responding. One possible reason for this is that Nic is thought to be bitter to rats (Smith and Roberts, 1995), and the higher 0.21 mg/ml Nic concentration may have altered the palatability of EtOH + Nic solution making it aversive for 50% of the rats. The findings of Flynn et al. (1989) indicated that Nic concentrations ≥ 0.05 mg/ml/base can increase aversive taste reactivity in non-selected Sprague-Dawley rats and that the initial taste reactions to Nic concentrations of 0.001 mg/ml/base to 0.025 mg/ml/base were comparable to that of distilled water (Smith and Roberts, 1995). The direct comparisons between Nic solutions and EtOH + Nic solutions may not be valid, and no research has been conducted to examine the palatability of EtOH + Nic solutions. However, the current study demonstrates that P rats are willing to work (even in the presence of EtOH alone) for solutions of Nic that have been shown to be bitter (when tested not in conjunction with EtOH) and potentially aversive in non-selected rat lines.

The EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic appeared to be the optimal EtOH + Nic solutions because P rats generally responding higher on all levers (Fig. 2) and generally obtained more reinforcers compared to the EtOH + 0.07 mg/ml Nic and EtOH+ 0.21 mg/ml Nic groups (Table 1). Self-administration of the EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic resulted in the highest EtOH (2 g/kg/ session) and Nic (2 mg/kg/session [0.7 mg/kg/base]) mean intake levels in the 60 minute sessions; EtOH intakes are comparable or higher than EtOH intakes when only EtOH solutions are available (Rodd et al., 2003).

The Nic intake levels for the EtOH + 0.14 mg/ml Nic group are higher than those observed in studies using extremely low concentrations of Nic (Dadmarz and Vogel, 2003; Maehler et al., 2000) and comparable to those observed during i.v. Nic operant studies (~1 mg/kg/base/session; Le et al., 2006; Donny et al., 1999; LeSage et al., 2002) and human daily Nic intake levels in low level smokers (1 mg/kg/day; Benowitz and Jacob, 1984). As a control, we examined whether P rats would self-administer Nic + Sacc solutions. The responses during acquisition (FR-1) for the Nic + Sacc solution increased from ninth session onward (60 minutes) (Fig. 5A). The rats maintained stable responses of Nic + Sacc with estimated Nic intakes of 1.3 mg/kg (0.46 mg/kg/base) during the 60 minute maintenance (FR-5) sessions (Fig. 5B), which is comparable to i.v. Nic self-administration observed in P rats (Le et al., 2006; Rezvani et al., 2010).

The willingness to concurrently self-administer EtOH + Nic is reflected by the pharmacologically relevant levels of both drugs in plasma following a self-administration session. The level of EtOH achieved is in the range described as a ‘binge’ episode (> 80 mg%) by NIAAA. In humans, normal cigarette and oral consumption of tobacco products (chewing and snuff) produce plasma levels of Nic of approximately 15 ng/ml (Benowitz, 1997). Our results demonstrated that P rats will orally self-administered Nic + Sacc and achieve blood nicotine levels (BNL) of 21 ng/ml, comparable to human Nic use. Temporal analysis of BNL in humans following Nic usages revealed that the only difference between cigarettes and oral Nic product is a slightly faster rise in BNL in smokers compared to oral users (Benowitz, 1997). Individuals that are excessively using Nic products (i.e., ‘heavy’ smokers) can readily obtain BNL of between 45–80 ng/ml, while ‘chain-smokers’ can reach levels of approximately 225 ng/ml (Russell et al., 1980). The BNL observed in P rats under the current EtOH + Nic experimental protocol would fall within the range of excessive or ‘heavy smokers’ (56 ng/ml). In addition, 3 hours after an operant session, P rats still had detectable levels of nicotine (approximately 8 ng/ml) and sustained levels of cotinine (41 ng/ml). BNL following i.v. Nic varies greatly between experiments (and is influenced by conditioning parameters, gender, strain, age of testing and Nic dose), but generally peaks around 15 ng/ml (Matta et al., 2007). Therefore, the current oral EtOH + Nic protocol results in BNL that can exceed that observed following i.v. Nic self-administration.

The co-abuse of alcohol with Nic is thought to increase the risk of alcohol-seeking and relapse further than alcohol use alone (Taylor et al., 2000). In support of this, pre-clinical studies demonstrated that Nic can reinstate EtOH-seeking behavior in Long-Evans rats (Le et al., 2003) and in P rats (Hauser et al., 2012) under operant conditions. Therefore, another goal of the current study was to determine the effects a history of chronic EtOH + Nic self-administration would have on seeking and relapse behaviors in P rats. The results show that P rats readily expressed drug-seeking behaviors for all of the EtOH + Nic solutions (Fig. 3) compared to extinction baseline. In fact, P rats with a history of EtOH + 0.07 mg/ml Nic expressed EtOH + Nic seeking behaviors for 3 consecutive sessions, longer than that observed in past research examining EtOH-seeking in P rats with a history of only EtOH self-administration (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2002a,b; Dhaher et al., 2010; Getachew et al., 2011; Hauser et al., 2012). Pre-extinction intake levels of EtOH + Nic also appear to influence the expression of drug-seeking behavior during PSR testing. EtOH + Nic responding was less expressed (amount and duration) in P rats with a past history of self-administering EtOH + 0.21 mg/ml Nic compared to other EtOH + Nic groups.

During relapse, P rats readily reacquired EtOH + Nic self-administration (Fig. 4) when the solutions were returned to the operant environment. Although increased responding following a period of deprivation was not observed under these conditions, the P rat readily reacquired operant responding for EtOH + Nic solutions at the same levels as before extinction training. The results support the utility of this model to study mechanisms underlying alcohol and drug relapse and its consequences.

In conclusion, these findings indicate that P rats will self-administer EtOH + Nic solutions and express drug-seeking and relapse behaviors for the combined solutions. Also, P rats will readily work for EtOH + Nic solutions while given concurrent access to EtOH alone. Most importantly, high concurrent pharmacologically relevant levels of EtOH and Nic in the blood following a period of self-administration were produced using the present model of EtOH + Nic co-use. Overall, the current findings begin to establish an animal model of concurrent EtOH + Nic co-use which could be employed to examine the consequences of chronic, voluntary EtOH + Nic.

Acknowledgments

The skillful technical assistance of Tylene Pommer and Victoria McQueen is gratefully acknowledged. Supported in part by NIAAA grants AA07611, AA07462, AA13522 (INIA), and AA019366. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIAAA or NIH.

References

- Abrams DB, Rohsenow DJ, Niaura RS, Pedraza M, Longbaugh R, Beatties MC, Binkoff JA, Noel NE, Monti PM. Smoking and treatment outcome for alcoholics: effects on coping skills, urge to drink and drinking rats. Beh Ther. 1992;23:283–297. [Google Scholar]

- Alen F, Gomez R, Gonzalez-Cuevas G, Navarro M, Lopez-Moreno JA. Nicotine causes opposite effects on alcohol intake: Evidence in an animal experimental model of abstinence and relapse from alcohol. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:1304–1311. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RL, Rodd ZA, Hsu CC, Lumeng L, Li TK, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. Effects of concurrent access to a single concentration or multiple concentrations of ethanol on ethanol intake by periadolescent high-alcohol-drinking rats. Alcohol. 2004;33:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL. Systemic absorption and effects of nicotine from smokeless tobacco. Adv Dent Res. 1997;11:336–341. doi: 10.1177/08959374970110030501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Jacob P., III Daily intake of nicotine during cigarette smoking. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1984;35:499–504. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1984.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biondolillo K, Pearce AR, Louder MC, McMickle A. Solution concentration influences voluntary consumption of nicotine under multiple bottle conditions. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;92:214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biondolillo KD, Pearce AR. Availability influences initial and continued ingestion of nicotine by adolescent female rats. Neuropsychobiology. 2007;55:73–80. doi: 10.1159/000103905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DC. Recent and remote extinction cues reduce spontaneous recovery. Q J Exper Psychol B. 2000;153:25–58. doi: 10.1080/027249900392986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist O, Ericson M, Johnson DH, Engel JA, Soderpalm B. Voluntary ethanol intake in the rat: effects of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor blockade or subchronic nicotine treatment. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;314:257–267. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00583-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero TJ. A critique of animal analogues of alcoholism. In: Majchrowicz E, Noble EP, editors. Biochemistry and Pharmacology of Ethanol. Vol. 2. New York: Plenum Press; 1979. pp. 533–560. [Google Scholar]

- Clark A, Lindgren S, Brooks SP, Watson WP, Little HJ. Chronic infusion of nicotine can increase operant self-administration of alcohol. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41:108–117. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadmarz M, Vogel WH. Individual self-administration of nicotine by rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;76:425–432. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daeppen JB, Smith TL, Danko GP, Gordon L, Landi NA, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Bucholz KK, Raimo E, Schuckit MA. Clinical correlates of cigarette smoking and nicotine dependence in alcohol-dependent men and women. The Collaborative Study Group on the Genetics of Alcoholism. Alcohol Alcohol. 2000;35:171–175. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/35.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaher R, Hauser SR, Getachew B, Bell RL, McBride WJ, McKinzie DL, Rodd ZA. The orexin-1 receptor antagonist SB-334867 reduces alcohol relapse drinking, but not alcohol-seeking, in Alcohol-Preferring (P) rats. J Addict Med. 2010;4:153–159. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181bd893f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donny EC, Caggiula AR, Mielke MM, Booth S, Gharib MA, Hoffman A, Maldovan V, Shupenko C, McCallum SE. Nicotine self-administration in rats on a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;147:135–142. doi: 10.1007/s002130051153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyr W, Koros E, Bienkowski P, Kostowski W. Involvement of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the regulation of alcohol drinking in Wistar rats. Alcohol Alcohol. 1999;34:43–47. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson M, Engel JA, Soderpalm B. Peripheral involvement in nicotine-induced enhancement of ethanol intake. Alcohol. 2000;21:37–47. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(99)00099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn FW, Webster M, Ksir C. Chronic voluntary nicotine drinking enhances nicotine palatability in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1989;103:356–364. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.103.2.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getachew B, Hauser SR, Dhaher R, Katner SN, Bell RL, Oster SM, McBride WJ, Rodd ZA. CB1 receptors regulate alcohol-seeking behavior and alcohol self-administration of alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;97:669–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick SD, Visker KE, Maisonneuve IM. An oral self-administration model of nicotine preference in rats: effects of mecamylamine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;28:426–431. doi: 10.1007/s002130050153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver SB, Rohsenow DJ, Colby SM, Dey AN, Abrams DB, Niaura RS, Monti PM. Interrelationship of smoking and alcohol dependence, use and urges to use. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:202–206. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser SR, Getachew B, Oster SM, Dhaher R, Ding Z-M, Bell RL, McBride WJ, Rodd ZA. Nicotine modulates alcohol-seeking and relapse by Alcohol-Preferring (P) rats in a time dependent manner. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:43–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01579.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölter SM, Engelmann M, Kirschke C, Liebsch G, Landgraf R, Spanagel R. Long-term ethanol self-administration with repeated ethanol deprivation episodes changes ethanol drinking pattern and increases anxiety-related behaviour during ethanol deprivation in rats. Behav Pharmacol. 1998;9:41–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. treating smokers with current or past alcohol dependence. Am J Health Beh. 1996;20:286–290. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Clinical implications of the association between smoking and alcoholism. In: Fertig J, Fuller R, editors. Alcohol and Tobacco: From Basic Science to Policy. NIAAA Research Monograph; Washington DC: 1995. pp. 171–185. [Google Scholar]

- Hurt RD, Eberman KM, Croghan IT, Offord KP, Davis LJ, Jr, Morse RM, Palmen MA, Bruce BK. Nicotine dependence treatment during inpatient treatment for other addictions: a prospective intervention trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:867–872. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John U, Hill A, Rumpf Hapke, Meyer C. Alcohol high risk drinking, abuse, and dependence among tobacco smoking medical care patients and the general population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003a;64:233–241. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00315-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John U, Meyer C, Rumpf HJ, Schumann A, Thyrian JR, Hapke U. Strength of the relationship between tobacco smoking, nicotine dependence and the severity of alcohol dependence syndrome criteria in a population-based sample. Alcohol Alcohol. 2003b;38:606–612. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katner SN, McBride WJ, Lumeng L, Li TK, Murphy JM. Involvement of CNS cholinergic systems in alcohol drinking of P rats. Addict Biol. 1997;2:215–223. doi: 10.1080/13556219772769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lajtha A, Sershen H. Nicotine: alcohol reward interactions. Neurochem Res. 2010;35:1248–1258. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallemand F, Ward RJ, De WP. Nicotine increases ethanol preference but decreases locomotor activity during the initial stages of chronic ethanol withdrawal. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42:207–218. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD. Effects of nicotine on alcohol consumption. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1915–1916. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000040963.46878.5D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Wang A, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Shaham Y. Nicotine increases alcohol self-administration and reinstates alcohol seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;168:216–221. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1330-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Li Z, Funk D, Shram M, Li TK, Shaham Y. Increased vulnerability to nicotine self-administration and relapse in alcohol-naive offspring of rats selectively bred for high alcohol intake. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1872–1879. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4895-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Lo S, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Marinelli PW, Funk D. Coadministration of intravenous nicotine and oral alcohol in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;208:475–486. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1746-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeSage MG, Keyler DE, Shoeman D, Raphael D, Collins G, Pentel PR. Continuous nicotine infusion reduces nicotine self-administration in rats with 23-h/day access to nicotine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;72:279–289. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00775-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester D, Freed EX. Criteria for an animal model of alcoholism. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1973;1:103–107. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(73)90062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Moreno JA, Trigo-Diaz JM, Rodriguez de FF, Gonzalez CG, Gomez de HR, Crespo GI, Navarro M. Nicotine in alcohol deprivation increases alcohol operant self-administration during reinstatement. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:1036–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehler R, Dadmarz M, Vogel WH. Determinants of the voluntary consumption of nicotine by rats. Neuropsychobiology. 2000;41:200–204. doi: 10.1159/000026660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matta SG, Balfour DJ, Benowitz NL, Boyd RT, Buccafusco JJ, Caggiula AR, Craig CR, Collins AC, Damaj MI, Donny EC, Gardiner PS, Grady SR, Heberlein U, Leonard SS, Levin ED, Lukas RJ, Markou A, Marks MJ, McCallum SE, Parameswaran N, Perkins KA, Picciotto MR, Quik M, Rose JE, Rothenfluh A, Schafer WR, Stolerman IP, Tyndale RF, Wehner JM, Zirger JM. Guidelines on nicotine dose selection for in vivo research. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;190:269–319. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0441-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride WJ, Li TK. Animal models of alcoholism: neurobiology of high alcohol- drinking behavior in rodents. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1998;12:339–369. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v12.i4.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan DE, Li M, Shide DJ. Differences between alcohol-preferring and alcohol-nonpreferring rats in ethanol generalization. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64:415–419. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JM, Stewart RB, Bell RL, Badia-Elder NE, Carr LG, McBride WJ, Lumeng L, Li TK. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of the Indiana University rat lines selectively bred for high and low alcohol preference. Behav Genet. 2002;32:363–388. doi: 10.1023/a:1020266306135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal R, Chappell AM, Samson HH. Effects of nicotine and mecamylamine microinjections into the nucleus accumbens on ethanol and sucrose self-administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1190–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olausson P, Ericson M, Lof E, Engel JA, Soderpalm B. Nicotine-induced behavioral disinhibition and ethanol preference correlate after repeated nicotine treatment. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;417:117–123. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00903-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page-Sharp M, Hale TW, Kristensen JH, Llett KF. Measurement of nicotine and cotinine in human milk by high-preformance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet absorption detection. J Chromatogr B Analyt Biomed Life Sci. 2003;796:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2003.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmatier MI, Coddington SB, Liu X, Donny EC, Caggiula AR, Sved AF. the motivation to obtain nicotine-conditioned reinforcers depends on nicotine dose. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:1425–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potthoff AD, Ellison G, Nelson L. Ethanol intake increases during continuous administration of amphetamine and nicotine, but not several other drugs. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1983;18:489–493. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(83)90269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezvani AH, Slade S, Wells C, Petro A, Lumeng L, Li TK, Xiao Y, Brown ML, Paige MA, McDowell BE, Rose JE, Kellar KJ, Levin ED. Effects of sazetidine-A, a selective alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor desensitizing agent on alcohol and nicotine self administration in selectively bred alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;211(2):161–74. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1878-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd ZA, McKinzie DL, Bell RL, McQueen VK, Murphy JM, Schoepp DD, McBride WJ. The metabotropic glutamate 2/3 receptor agonist LY404039 reduces alcohol-seeking but not alcohol self-administration in alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Behav Brain Res. 2006;171:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd ZA, Bell RL, Kuc KA, Murphy JM, Lumeng L, McBride WJ. Effects of concurrent access to multiple ethanol concentrations and repeated deprivations on alcohol intake of high-alcohol-drinking (HAD) rats. Addict Biol. 2009;14:152–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00140.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd-Henricks ZA, Bell RL, Kuc KA, Murphy JM, McBride WJ, Lumeng L, Li TK. Effects of concurrent access to multiple ethanol concentrations and repeated deprivations on alcohol intake of alcohol-preferring rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1140–1150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd-Henricks ZA, Bell RL, Kuc KA, Murphy JM, McBride WJ, Lumeng L, Li TK. Effects of ethanol exposure on subsequent acquisition and extinction of ethanol self-administration and expression of alcohol-seeking behavior in adult alcohol-preferring (P) rats: I. Periadolescent exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002a;26:1632–1641. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000036301.36192.BC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd-Henricks ZA, Bell RL, Kuc KA, Murphy JM, McBride WJ, Lumeng L, Li TK. Effects of ethanol exposure on subsequent acquisition and extinction of ethanol self-administration and expression of alcohol-seeking behavior in adult alcohol-preferring (P) rats: II. Adult exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002b;26:1642–1652. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000036302.73712.9D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd ZA, Bell RL, Kuc KA, Murphy JM, Lumeng L, Li TK, McBride WJ. Effects of repeated alcohol deprivations on operant ethanol self-administration by alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1614–1621. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell MAH, Jarvis MJ, Iyer R, Feyerabend C. Relation of nicotine yield of cigaretters to blood nicotine concentrations in smokers. Br Med J. 1980;280:972–975. doi: 10.1136/bmj.280.6219.972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe AL, Samson HH. Repeated nicotine injections decrease operant ethanol self-administration. Alcohol. 2002;28:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(02)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BR, Horan JT, Gaskin S, Amit Z. Exposure to nicotine enhances acquisition of ethanol drinking by laboratory rats in a limited access paradigm. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;142:408–412. doi: 10.1007/s002130050906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Roberts DC. Oral self-administration of sweetened nicotine solutions by rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;120:341–346. doi: 10.1007/BF02311182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Sobell LC, Kozolowski LT. Dual recoveries from alcohol and smoking problems. In: Fertig JB, Allen JS, editors. Alcohol and Tobacco: From Basic Science to Clinical Practice. NIAAA; Bethesda MD: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BJ, Graham JW, Cumsille P, Hansen WB. Modeling prevention program effects on growth in substance use: analysis of five years of data from the Adolescent Alcohol Prevention Trial. PrevSci. 2000;1:183–197. doi: 10.1023/a:1026547128209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolffgramm J, Heyne A. From controlled drug intake to loss of control: the irreversible development of drug addiction in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 1995;70:77–94. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(95)00131-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]