Abstract

Purpose

Despite the prevalence of musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders, the degree to which medical schools are providing students the knowledge and confidence to treat these problems is unclear. This study evaluated MSK knowledge in second and fourth year medical students using a newly developed written assessment tool and examined the maturation of clinical confidence in treating core MSK disorders.

Methods

Over a 3-year period, the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) MSK subject examination consisting of 75 items was administered to 568 second and fourth year students at a single institution. Students were also asked to rate their confidence in treating a selection of medicine/pediatric and MSK clinical scenarios on a 5-point Likert scale.

Results

Participation rate was 98%. The NBME MSK assessment score was 59.2±10.6 for all second year medical students and 69.7±9.6 for all fourth year medical students. There was a significant increase in NBME scores between the second and fourth years (p<0.0001). Students were more confident in treating internal medicine/pediatric conditions than MSK medicine conditions (p=0.001). Confidence in treating MSK medicine conditions did not improve between the second and fourth years (p=0.41).

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report increased MSK medicine knowledge as measured by a standardized examination after completing medical school core clinical rotations. Despite increased MSK knowledge, low levels of MSK clinical confidence among graduating students were noted. Further research is needed to determine the factors that influence MSK knowledge and clinical confidence in medical students.

Keywords: NBME musculoskeletal subject exam, musculoskeletal clinical scenarios

Musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders are one of the main problems encountered in primary care practices with 20–25% of new patient visits due to MSK pathology (1, 2). Approximately 92.1 million MSK encounters are reported annually (3). In 2004 the sum of direct expenditures in health care costs and indirect expenditures in lost wages in the United States due to MSK disorders was estimated at $849 billion. This represents 7.7% of the national gross domestic product (4).

The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) recently expressed concern that medical schools are inadequately preparing students for the evaluation and treatment of the growing burden of MSK problems (5). Educational deficiencies in MSK medicine have previously been identified in both American and Canadian medical school curricula (2, 6). Deficiencies in MSK knowledge may be related to insufficient time dedicated to MSK medicine instruction. In 2003 it was reported that almost 50% of United States medical schools had no required MSK basic science coursework or clinical clerkships (7). Approximately 75% of medical schools do not require a MSK clinical clerkship (7). Even in medical schools that provide enhanced MSK content in basic science and clinical curricula, little information is available regarding its influence on medical student MSK knowledge and clinical confidence. MSK assessment tools are limited in number and design, and may be suboptimal in their abilities to evaluate core MSK knowledge (6, 8). Additionally, growth in medical student MSK knowledge has not been compared to knowledge growth in core disciplines such as internal medicine and pediatrics using validated external measures of competency.

The purpose of this study was twofold. The first was to evaluate and compare MSK knowledge in second and fourth year medical students at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry using a newly developed MSK written assessment tool and determine if performance improves after greater clinical experience. Secondly, we aimed to compare the development of self-assessed clinical confidence in treating core MSK disorders with clinical confidence in treating core conditions encountered in internal medicine/pediatrics.

Methods

MSK instruction

The School of Medicine and Dentistry curriculum has early clinical exposure, and students have completed adult and pediatric ambulatory clerkship requirements by the end of year 2. The curriculum provides 82 hours of MSK content early in the undergraduate curriculum, exclusive of physical diagnosis. Of this, cadaveric extremity dissection during the first year constitutes approximately 30 hours. In year 2, the basic science of MSK medicine and rheumatology is covered in over 36 hours. There are two 8-hour modules that focus on the orthopedic clinical aspects of common MSK disorders. In the first year there is a module composed of 2 hours of lecture with 6 hours of small group problem-based learning (PBL) material covering basic upper and lower extremity MSK disorders. The second year curriculum also has 2 hours of lecture and 6 hours of small group PBL material covering orthopedic emergencies, pediatric orthopedics, and low back pain. The School of Medicine and Dentistry is one of many schools that do not require MSK medicine instruction during the clinically heavy final 2 years of the medical school curriculum.

Medical student groups

Five hundred and sixty-eight medical students from the School of Medicine and Dentistry participated in the study. Participants included 304 second year students from the classes of 2009, 2010, and 2011, and 264 fourth year students from the classes of 2008, 2009, and 2010. The class of 2009 and 2010 took the examination twice, once as second year and once as fourth year students.

Measures

MSK knowledge

Between May 2007 and February 2010, participants were administered the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) MSK subject examination at the end of their second and fourth years of medical school. The NBME MSK assessment tool is a web-based multiple-choice examination developed in 2006 in conjunction with the Bone and Joint Decade. Test materials were drawn from secure NBME item pools, reviewed, and approved by an external volunteer interdisciplinary MSK task force composed of basic scientists and clinicians. The MSK subject examination is similar in format to the NBME subject examinations available in core clinical science disciplines, including Medicine and Pediatrics. Subject examinations are intended to complement other sources of information about the educational progression of medical students, and they are primarily designed for use as final examination after courses and clerkships.

The NMBE MSK subject examination comprises 75 items, with 14 basic science and 61 clinical items plus a brief tutorial; examinees are allotted 1 hour 55 min for completion. The KR20 reliability of the examination in the initial reference group of senior students from three participating schools was 0.86; reliabilities greater than 0.85 are considered acceptable for low stakes examinations. The mean percent correct score was 69.7 with an SD of 13.2. Mean scores and SD correspond closely to performance on other NBME discipline based ‘shelf’ examinations. The School of Medicine and Dentistry participated in pilot testing and validation of the examination.

The examination was administered to students during a translational science course which included MSK topics but did not review prior MSK coursework. The exam was required but students who missed the exam due to illness or out of town obligations did not have to make up the examination. Being a part of curricular evaluation, the score was not part of a course grade and there was no special preparation. Accordingly this was a ‘low stakes’ examination, yet provided a unique opportunity for self-assessment of MSK medicine knowledge.

Clinical confidence

Participants’ clinical confidence in MSK medicine and internal medicine/pediatrics was measured simultaneously using a 10-item self-assessment tool to quantitate self-reported confidence in evaluating and treating select clinical scenarios. This clinical confidence tool is similar to those used in prior MSK curricular evaluation studies and is not validated (9, 10). These 10 self-assessment items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale. There were two questions that asked students to rate their confidence in evaluating and treating common MSK disorders. Students were then asked to rate their confidence in evaluating four MSK clinical scenarios and four internal medicine/pediatrics scenarios. The MSK clinical scenarios were ankle pain, knee pain, shoulder pain, and wrist pain. The internal medicine/pediatrics scenarios were chest pain, delirium, dyspnea, and febrile infant. The mean MSK medicine and internal medicine/pediatrics clinical confidence scores were computed for each participant in the second and fourth years of medical school.

Statistical analysis

We first performed descriptive and univariate analyses of participants’ knowledge and confidence scores. Normalcy of variables was assessed using the Shapiro Wilk test. All variables were found to be normally distributed.

We then performed one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess for overall differences in mean knowledge and confidence scores between classes. Analyses were conducted for both the second (2009–2011) and fourth (2008–2010) year classes. We then excluded all paired data (dependent scores) and performed an independent samples t-test to compare second and fourth year scores.

To compare participants’ second and fourth year knowledge and confidence scores over time, we performed paired sample t-tests on dependent scores for the classes of 2009 and 2010. Paired analyses were also conducted to compare knowledge and confidence scores within second and fourth year classes. Relationships between MSK knowledge and MSK and internal medicine/pediatrics clinical confidence were then assessed by Pearson correlations.

In reporting results, all tests were two-sided and we assumed statistical significance at p<0.05. Analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.1 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The Research Subjects Review Board at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry approved this curricular evaluation study.

Results

Student participation

A total of 568 medical students completed the NBME MSK subject examination between May 2007 and February 2010. Overall participation rate was 98%, with Table 1 presenting the details of participation by class year and by training level.

Table 1.

Participation rates in NBME musculoskeletal (MSK) knowledge assessment by class

| Students completing assessment | Class size | Participation rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Second year medical students | |||

| Class of 2009 | 103 | 103 | 100 |

| Class of 2010 | 97 | 101 | 96 |

| Class of 2011 | 104 | 104 | 100 |

| Total | 304 | 308 | 99 |

| Fourth year medical students | |||

| Class of 2008 | 88 | 90 | 98 |

| Class of 2009 | 86 | 87 | 99 |

| Class of 2010 | 90 | 94 | 96 |

| Total | 264 | 271 | 97 |

Note: A total of 304 second year medical students and 264 fourth year medical students completed the NBME MSK knowledge assessment. Overall participation rate was 98%.

MSK knowledge

The mean score for the NBME MSK subject examination for all second year medical students was 59.2±10.6. The mean score for the NBME MSK subject examination for all fourth year medical students was 69.7±9.6. To compare second year and fourth year medical students, we removed all paired data (dependent scores) and found a statistically significant increase in NBME scores (p<0.0001.) Table 2 shows NBME MSK knowledge assessment scores for each class. There was a statistically significant difference between year 2 and year 4 scores for all classes.

Table 2.

NBME musculoskeletal knowledge assessment scores [mean (SD)] for years 2 and 4 by medical student class

| MSK knowledge | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | All classes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 2 | 61.2 (10.9) | 59.7 (10.6) | 57.0 (10.1) | 59.2 (10.6) | |

| Year 4 | 67.1 (10.3) | 71.5 (8.8)† | 70.2 (9.3)† | 69.7 (9.6)* |

To compare second year and fourth year medical students, we removed all paired data (dependent scores) and found a statistically significant increase in NBME scores (p<0.0001.).

For students who took the examination twice, longitudinal analyses over time showed statistically significant changes (p<0.0001).

For students who took the examination twice, longitudinal analyses revealed statistically significant differences from year 2 to year 4. Mean scores increased by 10.7 points (p<0.0001) and 11.0 points (p<0.0001) for the classes of 2009 and 2010, respectively.

Clinical confidence

Table 3 shows the mean clinical confidence scores (5-point Likert scale) for each group of medical students that took the test. For all students, clinical confidence in internal medicine/pediatrics was higher than MSK medicine. Clinical confidence for internal medicine/pediatrics improved between year 2 and year 4, but clinical confidence for MSK medicine was not significantly changed between year 2 and year 4.

Table 3.

Musculoskeletal (MSK) and internal medicine/pediatrics clinical confidence scores (mean (SD)) for years 2 and 4 by medical student class

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | All classes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSK confidence | |||||

| Year 2 | 2.7 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.8) | 2.8 (0.8) | 2.8 (0.8)* | |

| Year 4 | 2.8 (0.8) | 2.9 (0.9) | 2.8 (0.9) | 2.9 (0.9)† | |

| Internal medicine/pediatrics confidence | |||||

| Year 2 | 3.5 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.6) | 3.5 (0.6) | 3.6 (0.6)* | |

| Year 4 | 4.2 (0.6) | 4.1 (0.6) | 4.1 (0.5) | 4.2 (0.6)†,‡ | |

In year 2, a statistically significant difference (p=0.001) exists between MSK and internal medicine/pediatrics confidence scores.

In year 4, a statistically significant difference (p=0.001) exists between MSK and internal medicine/pediatrics confidence scores.

From year 2 to year 4, a statistically significant increase in internal medicine/pediatrics clinical confidence scores (p= < 0.0001). By contrast, clinical confidence scores in MSK medicine did not significantly differ (p=0.41).

The mean second year clinical confidence score for scenarios in internal medicine/pediatrics was 3.6±0.6. The mean second year clinical confidence score for scenarios in MSK medicine was 2.8±0.8. A statistically significant difference (p=0.001) exists between the year 2 MSK and internal medicine/pediatrics confidence scores (Table 3).

The mean fourth year internal medicine/pediatrics clinical confidence score was 4.2±0.6. The mean fourth year MSK clinical confidence score was 2.86±0.86. Again, a statistically significant difference (p=0.001) exists between the year 4 MSK and internal medicine/pediatrics confidence scores (Table 3).

Longitudinal analyses revealed a statistically significant increase in internal medicine/pediatrics clinical confidence scores from year 2 to year 4 (p= < 0.0001). By contrast, clinical confidence scores in MSK medicine did not significantly differ from year 2 to year 4 (p=0.41).

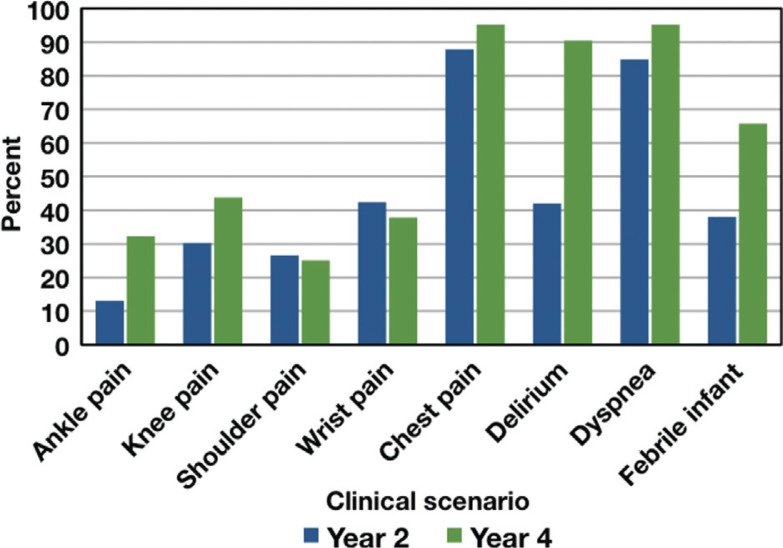

Fig. 1 depicts the percentage of second and fourth year medical students reporting they were ‘somewhat confident’ or ‘very confident’ in treating each clinical scenario. Students at the second year level reported higher confidence in treating internal medicine/pediatrics core conditions than MSK core conditions. This difference in confidence becomes even greater in students at the fourth year level.

Fig. 1.

Clinical confidence by scenario.

Correlation between knowledge and confidence

There was no correlation between NBME MSK knowledge exam scores and clinical confidence scores for either internal medicine/pediatrics scenarios (r 2=0.06, p=0.34) or MSK medicine scenarios for second year medical students (r 2=0.10, p=0.08). Similarly, there was no correlation between NBME MSK knowledge exam scores and clinical confidence scores for internal medicine/pediatrics scenarios for fourth year medical students (r 2=0.08, p=0.2). There was a weak, positive correlation between NBME MSK assessment scores and clinical confidence scores for MSK medicine scenarios for fourth year medical students (r 2=0.13, p=0.04).

Discussion

Over the past decade, concerns have been raised by the AAMC regarding the adequacy of MSK training (5). Recent studies have reported on deficiencies in MSK knowledge (6, 8, 10). These studies have lead to concerns regarding the adequacy of MSK training and the subsequent ability of future physicians to adequately care for the ever-increasing burden of MSK disorders.

Historically, the use of MSK assessment tools in evaluating and documenting MSK knowledge have been limited by availability, design, and application. In 1998, an MSK assessment tool was developed and reported on by Freedman and Bernstein (8). This assessment tool was referred to as a basic competency examination in MSK medicine and consisted of 25 short answer questions. Orthopedic residency program directors were asked to rate each question for importance. Criterion validity was then addressed by administering the exam to orthopedic chief residents. There was some criticism regarding the source of validation, and it was broadened and evaluated by internal medicine program directors (6). The MSK Basic Competency examination represented a significant advancement in evaluation and has been employed in recent studies (9–11). Nevertheless, its content outline, brevity, and item format raise questions about the validity and generalizability of results as measures of overall MSK knowledge. For these reasons, we used a simplified tool to quantitate confidence only and relied on the validated MSK exam to assess knowledge.

The standardized MSK medical knowledge assessment method used in the current study is based upon commonly encountered clinical scenarios with multiple-choice questions. The overall format is identical to other NBME clinical science discipline subject test examinations. The exam blueprint was approved by an interdisciplinary task force of surgical and medical MSK experts, and the overall examination pilot tested to establish performance metrics. Individual test items were drawn from secure validated NBME test libraries and evaluate knowledge of disease processes and therapeutics as well as diagnostic and clinical reasoning.

When comparing the current study's results with previous MSK curricular reports, there are similarities as well as important differences (6, 8, 10). Previous reports noted low levels of clinical confidence in evaluating MSK disorders as well as low levels of MSK knowledge among medical students. In the current study, low levels of clinical confidence in evaluating MSK medicine disorders were similarly observed. While clinical confidence for core medicine/pediatric conditions was either high at second year or increased to a higher level by fourth year, MSK medicine confidence remained much lower in both the second and fourth years. These findings of low clinical confidence in MSK medicine are similar to reports by Day et al. (9–12). It should be noted that these authors reported on a sampling of students throughout training and did not specifically evaluate pre-clinical versus clinical time periods.

However, the MSK knowledge assessment results were noticeably different than prior studies. Initially low levels of MSK knowledge were observed during the second year, but by the fourth year a statistically significant increase in MSK knowledge was noted. In our cohort, clinical experience resulted in an increase in MSK knowledge as measured by the NBME MSK subject exam. In fact, by the end of the fourth year, the exam results noted a mean of 69.7% correct, and this number approaches the anticipated or targeted mean score of 70% correct for established core NBME subject exams and the USMLE step exams. The current study is the first to specifically evaluate pre-clinical (second year) versus end of training post-clinical (fourth year) performance and to observe a high level of MSK knowledge among graduating medical students.

Given the frequency of MSK disorders encountered in general medical practice (1, 2), the current study's finding that MSK clinical self-confidence as determined by our tool does not change with an increase in MSK knowledge among graduating medical students is concerning. While we acknowledge that measures of confidence should not be interpreted as determinants of competence, we are concerned that medical students who graduate with a lower level of MSK clinical confidence may either refer MSK problems to subspecialists prematurely or order unnecessary or expensive diagnostic. These possibilities could contribute to the escalation of health care costs, both directly and indirectly.

This study has several limitations. First, the NBME MSK subject examination used to measure an increase in knowledge is new, and reliability information is based on a relatively small cohort of students at a few institutions. The examination was administered under ‘low stakes’ conditions where results did not affect student grades or transcripts. It is likely that participants had varying degrees of motivation. Performance under high stakes conditions might be different.

Additionally, since only one form of the NBME MSK subject examination currently exists, students in the Classes of 2009 and 2010 took the same examination in their second and fourth years of medical school. This creates the potential for recall bias. To minimize this bias, students were not informed that they would be taking the same exam again in their final year. To evaluate this potential bias further, we stratified the data and removed all paired data (dependent scores) or those students who take the exam twice (Table 2). When excluding paired data (dependant scores), a statistically significant difference (p<0.0001) was noted for unpaired year 2 (58.2 SD 10.4) and year 4 (69.3 SD 9.6) students.

Another limitation is that our confidence self-assessment tool is not validated although as indicated, it was based on a previously published tool (9, 10). However, because our students completed this self-assessment tool for all clinical scenarios at the same time, we believe that comparisons of the scores for MSK scenarios with internal medicine/pediatrics scenarios is appropriate.

A review of the literature suggests that this is the first study to report a high level of MSK medicine knowledge among graduating medical students. The study introduces the NBME MSK subject examination as a valid and reliable interdisciplinary external multiple-choice MSK assessment tool. Large numbers of participants and high participation rates for both second and fourth year students strengthen the findings of the study. This minimizes bias that can be seen in curriculum evaluation studies where students who are either pleased or dissatisfied with the curriculum participate more frequently. Despite increased levels of MSK knowledge, low levels of MSK clinical confidence were noted in our study and this is similar to the low levels reported in other MSK assessment studies (2, 8, 10). Higher levels of clinical confidence in core internal medicine/pediatrics may be due, in part, to a larger volume of encounters in internal medicine and pediatric conditions with reinforcement of appropriate evaluation of these conditions during required clerkships during the third and fourth years.

A number of studies have reported a disparity between the curricular time in medical school and the prevalence of MSK disorders (2, 13, 14). Similar to the majority of medical schools, the School of Medicine and Dentistry requires exposure to MSK medicine and disorders only during years 1 and 2. No MSK courses or electives are required in years 3 and 4, and it is unclear what aspects of the clinical years are influencing and contributing to the increase in MSK knowledge. Further research should help to determine the factors that lead to increased MSK knowledge in the clinical years and identify what increases or decreases MSK clinical confidence. Finally, clinical skills were not considered in this study. It would be interesting to evaluate whether clinical skills in MSK medicine, specifically physical examination of the extremities and spine, paralleled changes in either knowledge or confidence.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

References

- 1.De Inocencio J. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal pain in primary care. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:431–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.028860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinney SJ, Regan WD. Educating medical students about musculoskeletal problems. Are community needs reflected in the curricula of Canadian medical schools? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1317–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hing E, Cherry DK, Woodwell DA. National ambulatory medical care survey: 2004 summary. Adv Data. 2006;374:1–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. The burden of musculoskeletal disease in the United States. 2nd ed. Rosemont, IL: 2011. p. ix. ISBN 978-0-89203-749-0 http://boneandjointburden.org. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical School Objectives Project. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2005. Report VII. Contemporary issues in medicine: musculoskeletal medicine education; pp. 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freedman KB, Bernstein J. Educational deficiencies in musculoskeletal medicine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:604–8. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200204000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Caprio MR, Covey A, Bernstein J. Curricular requirements for musculoskeletal medicine in American medical schools. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:565–7. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200303000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freedman KB, Bernstein J. The adequacy of medical school education in musculoskeletal medicine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1421–7. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199810000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeh AC, Franko O, Day CS. Impact of clinical electives and residency interest on medical students’ education in musculoskeletal medicine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:307–15. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Day CS, Yeh AC, Franko O, Ramirez M, Krupat E. Musculoskeletal medicine: an assessment of the attitudes and knowledge of medical students at Harvard Medical School. Acad Med. 2007;82:452–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31803ea860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Day CS, Yu YR, Yeh AC, Newman LR, Arky R, Roberts DH. Musculoskeletal preclinical medical school education: meeting an underserved need. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:733–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Day CS, Ahn CS. Commentary: the importance of musculoskeletal medicine and anatomy in medical education. Acad Med. 2010;85:401–2. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181cd4a89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernstein J, Alonso DR, DiCaprio M, Friedlaender GE, Heckman JD, Ludmerer KM. Curricular reform in musculoskeletal medicine: needs, opportunities, and solutions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;415:302–8. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000093922.26658.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clawson DK, Jackson DW, Ostergaard DJ. Its past time to reform the musculoskeletal curriculum. Acad Med. 2001;76:709–10. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200107000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]