Neuropathic pain affects up to 8% of the population,1 causing significant distress and morbidity. Good evidence-based treatment is available,2 so early diagnosis is important. Recent publicity and guidelines, and increasing prevalences of age-related causes of neuropathic pain (including postherpetic neuralgia and diabetic neuropathy), have led to increasing rates of diagnosis and treatment in primary care. Gabapentin is one of the recommended mainstays of evidence-based treatment.3

Unfortunately, our clinical experience suggests that gabapentin is now prevalent as a drug of abuse. The drug’s effects vary with the user, dosage, past experience, psychiatric history, and expectations. Individuals describe varying experiences with gabapentin abuse, including: euphoria, improved sociability, a marijuana-like ‘high’, relaxation, and sense of calm, although not all reports are positive (for example, ‘zombie-like’ effects). In primary care, an increasing number and urgency of prescription requests cannot necessarily be explained by the increased number of cases of neuropathic pain. In the substance misuse service, the numbers admitting to using gabapentin (local street name: ‘gabbies’, approx £1 per 300 mg) are also growing.

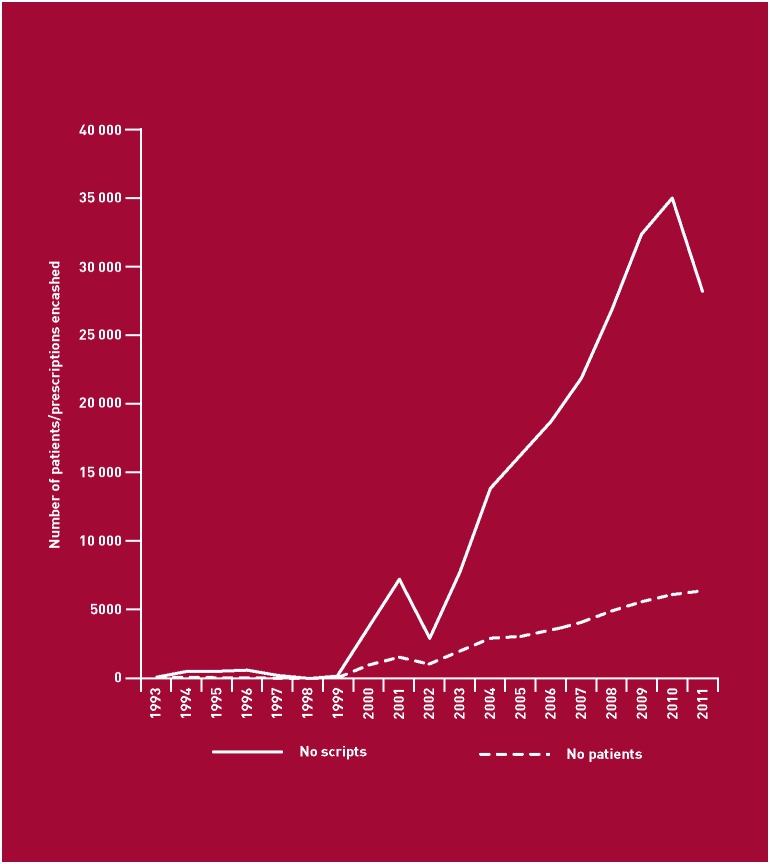

Prescribing data from the Tayside region of Scotland show a rise in the number of patients receiving gabapentin, and an exponential rise in the total number of prescriptions issued, particularly since it was licenced for postherpetic neuralgia in 2002 (Figure). In the substance misuse services in Tayside in 2009, we found that of those who had been attending for at least 4 years (n = 251), 5.2% were currently receiving gabapentin on prescription, with a mean dose of 1343 mg, and were >3 times more likely to admit to non-medical use of analgesics (P = 0.006). Meanwhile, of 1400 postmortem examinations in Central, Tayside, and Fife regions of Scotland in 2011, 48 included gabapentin in their toxicology report, with 36 also including morphine and/or methadone, indicating recent possible opioid dependence. Gabapentin is easily prescribed without restriction, and escalating doses are recommended.3,4 It is therefore easy to facilitate any misuse and addiction potential, and to stock the black market. A recent police report indicates the increasing tendency to use gabapentin as a ‘cutting agent’ in street heroin (and to recover gabapentin on the street and in prisons), further adding to the abuse and danger potential.5 Like opiates, gabapentin is fatal in overdose; unlike opiates, there is no antidote and the long half-life instils the need for prolonged, intensive management of overdose.

The epidemiology of gabapentin misuse needs further detailed and urgent assessment, including cross-linking data from Police, NHS, and other sources. We should consider introducing routine gabapentin testing in urine drug screens. This will inform clinical and political approaches to this possible new and dangerous type of substance misuse, as well as safe management of the distress caused by neuropathic pain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Torrance N, Smith BH, Bennett MI, Lee AJ. The epidemiology of chronic pain of predominantly neuropathic origin. Results from a general population survey. J Pain. 2006;7(4):281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finnerup NB, Sindrup SH, Jensen TS. The evidence for pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2010;150(3):573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. Pharmacological management of neuropathic pain in non-specialist settings. NICE Clinical Guideline 96. London: NICE; 2010. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG96 (accessed on 4 Jul 2012). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.BMA, Royal Pharmaceutical Society. British National Formulary, 62 (September 2011) London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scottish Drug and Crime Enforcement Agency, Forensic Science Unit. Report on the quality of diamorphine seized in Scotland, 2010–2011. Paisley: SCDEA; 2011. http://www.communityplanningaberdeen.org.uk/nmsruntime/saveasdialog.asp?lID=5715&sID=1712 (accessed on 4 Jul 2012). [Google Scholar]