Abstract

Purpose

This study investigates measures of family conflict, family management, and family involvement at ages 10–12, 13–14, and 15–18 as predictors of adult depression, anxiety, and substance use disorder symptoms classes at age 27. The objective was to assess the relative influence on adult outcomes of each family predictor measured similarly at different points in adolescent development.

Methods

Data are from the Seattle Social Development Project, a theory-driven longitudinal study that began in 1985 with 808 fifth-grade students from 18 Seattle public elementary schools. A Latent Class Analysis of adult outcomes was followed by bivariate and multivariate models for each family predictor. Of the original 808 participants, 747 participants (92% of the original sample) had available data at age 27 on the mental health and substance use latent class indicators. Missing data were handled using full-information maximum likelihood estimation.

Results

Four latent classes were derived: a “low disorder” symptoms class, a “licit substance use disorder symptoms” class, a “mental health disorder symptoms” class, and a “comorbid” class. Multivariate results show that family conflict is the strongest and most consistent predictor of the adult mental health and substance use classes. Family management, but not family involvement, was also predictive of the adult outcome classes.

Conclusions

It is important to lessen family conflict and improve family management to prevent later mental health and substance use problems in adulthood.

Keywords: Family conflict, family management, family involvement, mental health, substance use, comorbidity, adolescence, adulthood

INTRODUCTION

Prolonged exposure to chronic stress from family adversity is known to impair the health and development of children at different life stages [1, 2]. For example, there is evidence that child abuse of various forms (e.g., physical, sexual, psychological) increases the risk of later depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders during adolescence and adulthood [1]. As noted elsewhere [3], even less severe forms of family adversity, such as persistent arguing, sibling aggression, and overt hostility among family members are harmful to children at the time and in later years [4–6]. In a prospective study by Herrenkohl and colleagues [5], high initial levels and growth in family conflict during adolescence predicted a significant increase in the risk of adult stressful life events. Stressful life events predicted, in turn, more depressive symptoms. In another study, Amato and Sobolewski [7] found that divorce and marital discord increased the risk of poorer psychological functioning among adult children 19 years of age and older.

A study by Paradis et al. [8] examined the long-term impact of frequent arguing in the family by age 15. Outcomes at age 30 included major depression and alcohol abuse and dependence. The odds of adult depression diagnosis were 3 times greater for those in the sample from families in which arguments occurred frequently. For alcohol abuse and dependence, the odds were nearly 3 times greater for those whose families argued more (OR = 2.9).

In another study, Reinherz et al. [6] found a significant association between low family cohesion by age 15 and adult depression diagnosis between the ages of 18 and 26. Low family cohesion also predicted substance use disorders among adult children of both depressed and non-depressed parents in Nomura et al.’s [9] 10-year longitudinal investigation.

Other aspects of family life have been investigated as predictors of adult substance use and mental health problems [10, 11]. For example, Guo and colleagues [11] found that parental monitoring and clearly defined family rules measured at age 16 lessened the risk of alcohol abuse and dependence in those studied at age 21. Elsewhere, Arria et al. [10] found that strong parental monitoring in high school protected adolescents from excessive drinking in college.

Positive family experiences, such as participating together in leisure and recreational activities, sitting down to family meals, and regularly talking together about school and friends can also promote positive youth development [12]. However, further research is needed to show if these experiences affect adult functioning, as do other family predictors. It is also necessary to look more closely at which aspects of family functioning, both negative (e.g., conflict) and positive (e.g., family involvement), are most directly related to adult functioning, and from which points before and during adolescence they are most predictive. To date, research has mainly focused on family risk and protective factors studied cross-sectionally or longitudinally over short periods. Rarely has research examined how aspects of family life, studied over time, relate to the onset of much later problems in adulthood [5]. Longitudinal studies of this form can deepen understanding of the development and prevention of costly adult mental health and substance abuse symptoms and disorders. Finally, in that mental health and substance use symptoms disorders often overlap, it is important that researchers examine issues of symptom comorbidity [13, 14]. Doing so will further inform preventive interventions [15].

Objectives

Objectives are to study family predictors (family conflict, family management, and family involvement) of adult depression, anxiety, and substance use disorder symptoms, modeled as latent classes. Predictors were measured similarly at ages 10–12, 13–14, and 15–18 to coincide with the developmental periods of late childhood, early adolescence, and mid/late adolescence. Outcome classes were derived using Latent Class Analysis (LCA), a person-centered approach that accounts for correlations among observed variables.

METHODS

Sample

Data are from the Seattle Social Development Project (SSDP), a theory-driven longitudinal study that began in 1985 with fifth grade students from 18 Seattle public elementary schools [16]. Of those eligible, 808 students (77% of the population) were enrolled in the longitudinal study. This acceptance rate is comparable to other studies that have recruited participants from school settings [17, 18].

Data are from fall of students’ fifth-grade year at age 10, and annually thereafter to age 16. Data were also collected when participants were 18 years of age and then again at age 27. Procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Review Committee of the University of Washington.

The SSDP sample is ethnically diverse (47% European American, 26% African American, 22% Asian American, and 5% Native American) and gender balanced (51% male). More than 52% of the sample is from low-income households, according to families’ eligibility for the National School Lunch/School breakfast program when children of the study were in grades 5–7. Of the original participants still living at age 27, 94% were reassessed (n = 747).

Measures

Outcome: Mental health and substance use disorder symptoms (age 27)

At age 27, mental health and substance use disorder symptoms were measured using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) [19]. The DIS has been shown to be valid and reliable in studies of psychiatric disorders among adults [20–23]. Major depressive symptoms were measured by calculating the total number, up to 9, of past-year symptoms, including anhedonia, weight changes, sleep problems, psychomotor agitation or retardation, fatigue, feelings of sadness, concentration problems, and suicidal ideation (Mean = 1.5, SD=2.96; Cronbach α = .97). General anxiety disorder symptoms were measured by summing the total number, up to 6, of past-year anxiety symptoms, including excessive anxiety and worry, difficulties in controlling worry, restlessness, fatigue, concentration difficulties, sleep disturbance, and irritability (Mean = 1.97, SD=1.94; Cronbach α = .79). Alcohol use disorder symptoms were measured by calculating the total number, up to 11, of past-year alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms, including a failure to fulfill major role obligations, recurrent alcohol-related legal problems, a development of tolerance to alcohol, experiencing withdrawal symptoms, increased intake amount, and a great deal of time spent in activities necessary to obtain alcohol (Mean = .92, SD=1.84; Cronbach α = .84). Nicotine dependence symptoms were measured by summing the total number, up to 7, of past-year nicotine dependence symptoms, including a development of tolerance to nicotine, experiencing withdrawal symptoms, increased intake amount, and persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control cigarette use (Mean = .81, SD=1.44; Cronbach α = .79). Finally, marijuana use disorder symptoms were measured by calculating the total number, up to 11, of past-year marijuana abuse and dependence symptoms, including a failure to fulfill major roles, recurrent marijuana use in hazardous situations, recurrent marijuana-related legal problems, a development of tolerance to marijuana, withdrawal experiences, and persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down on marijuana use (Mean = .38, SD=1.23; Cronbach α = .84).

Family Functioning

Measures of family conflict, family management, and family involvement use comparable items at ages 10–12, 13–14, and 15–18. However, due to changes in the main survey instrument, there is some variation in the indicators and response options that comprise each predictor scale. Although scales vary in the overall number of indicators available at each study wave, the scales themselves are conceptually similar and consistent with the theoretical constructs of interest. Scale indicators were standardized before they were combined. The composite measures were then standardized around their grand means to allow each scale mean to be compared against the others.

Family conflict is based on 2 indicators at ages 10–12. These indicators reflect the extent to which family members talk things out (reverse coded) and get along (reverse coded). Each indicator was scored using a 4-point scale (1 = YES!, 2 = yes, 3 = no, 4 = NO!). At subsequent ages, an additional 3 items comprise the family conflict scales. These include family members’ criticizing one other, arguing, and yelling. Items were scored on a 5-point scale (1 = almost never, 2 = seldom, 3 = sometimes, 4 = fairly often, 5 = almost always). Higher composite scores overall reflect more conflict in the family. Scale reliabilities (Cronbach’s α) range from .73 to .79 across the 3 age periods.

Family management combines 6 indicators of parental monitoring, rules within the family, and punishments and rewards for behavior. Indicators reflect parents’ knowledge of students’ whereabouts, the clarity of rules within the family, time the child and parents spent discussing important issues, parents’ use of positive feedback to reward school achievement, parents’ acknowledgement of students’ positive behavior, and parents’ use of punishment (reverse coded). At age 18, the item assessing parental punishment was not included in the administered survey, and was thus not included in the scale for that age. Each item was scored 1 = NO!, 2 = no, 3 = yes, 4 = YES! Higher scores reflect better management practices within the family. Scale reliabilities range from .66 to .76.

Family involvement was based on 9 items that pertain to activities of youth and their families. Activities include working around house (Yes/No), walking with parents (Yes/No), doing recreational activities with parents (Yes/No), doing crafts with parents (Yes/No), cooking with parents (Yes/No), going to a theater with parents (Yes/No), having meals together (1 = none, 2 = one, 3 = two, 4 = three), talking about school (1 = never or almost never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, 4 = all of the time), and getting help on homework from parents (1 = NO!, 2 = no, 3 = yes, 4 = YES!). At age 18, only one item, ‘talking about school,’ was available, and thus is the sole indicator at that age. Higher scores reflect more involvement in the family. Scale reliabilities range from .52 to .61.

Covariates include gender (0 = female, 1 = male); race/ethnicity (3 dummy variables, each representing African American, Asian American, and Native American, with Caucasian as the reference group); and low income (eligibility for free or reduced-price school lunch in fifth or sixth grade for participating youth). A measure of childhood delinquency at ages 10–12 was included in the analysis because prior research shows it to be a consistent predictor of substance use and mental health problems in adulthood [11, 24, 25]. Delinquency items include shoplifting, breaking into a building, stealing money, damaging property, and being arrested by the police. The number of endorsed items was divided by the total number of items at that age, and then combined. A measure of childhood internalizing problems at ages 10–12 was also included. This measure used items from the Child Behavior Checklist [26] and is based on items such as “cries a lot,” “deliberately harms self or attempts suicide,” “underactive, slow moving, or lacks energy,” “clings to adults or too dependent,” and “too fearful or anxious.” Another covariate is frequency of early substance use, a measure that captures the number of times youth participants used alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana at ages 13–14. Data on substance use were not available in the study before age 13.

Analysis

Latent Class Analysis (LCA) [27, 28] was conducted using Mplus 5.2 [29]. In LCA, associations among measured (observed) variables are thought to be “explained” by an unobserved (latent) categorical construct. In the LCA, model fit is assessed by: (a) the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) and the sample-size-adjusted Bayesian Information Criteria (SABIC); (b) the Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test and the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (lower p-value indicates that the k class model is preferable over k-1 class model); and (c) entropy (ranging from 0 to 1; higher entropy scores typically indicate a better fit to the data; [for more details about fit statistics, see 30, 31–33]).

After identifying the optimal model solution, we examined bivariate associations between each family predictor and the LCA-derived adult mental health and substance use “classes,” using pseudo-class Wald chi-square tests [34]. These tests take into account the uncertainty of class assignments by using multiple random draws from the distribution of the posterior class probabilities [29, 34]. Multivariate regression models in the final step of the analysis focus on the conditional associations of the family predictors and the adult outcome classes, after accounting for covariates.

Missing Data

Missing data is low due to the strong retention of participants and high rate of completion for each survey assessment. Of the original 808 participants, 747 participants (92% of the original sample) had available data on the mental health and substance use latent class indicators at age 27. Missing data in the exogenous and endogenous variables resulted in final analysis samples at ages 10–12 of 670 (83% of the original sample), 672 (83% of the original sample) at ages 13–14; and 654 (81% of the original sample) at ages 15–18. Missing data were handled in MPlus using full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation [35–37].

RESULTS

Table 1 provides results of the LCA test in which different class solutions were considered. Overall, the 4-class solution fit the data best. Results show that adding a fifth class did not significantly improve the referenced fit statistics. Entropy remained over .9 through the 4-class solution, indicating a “clear” class assignment. Additionally, results showed the 4-class solution provided conceptually distinct and meaningful subgroups for the analysis sample.

Table 1.

Fit indices for latent class models (selected four-class model indicated by shading)

| Number of classes | BICa | SABIC | Log likelihood | Number of parameters | Entropy (average class probabilities) | Adjusted LRT b (p-value) | BLRT c (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-class | 13529.00 | 13513.12 | −6747.96 | 5 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 2-class | 10462.49 | 10427.56 | −5194.86 | 11 | .95(.99,.98) | < .001 | < .001 |

| 3-class | 9701.27 | 9647.29 | −4794.40 | 17 | .92(.99,.97,.95) | < .001 | < .001 |

| 4-class | 9283.82 | 9210.79 | −4565.83 | 23 | .93 (.97,.97,.96,.95) | .001 | < .001 |

| 5-class | 9476.78 | 9400.57 | −4659.00 | 24 | .84(.82,.9,.87,1,.9) | e d | e d |

Note:

Decrease greater than 6 indicates “strong” improvement in fit [40]

Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test

Parametric Bootstrapped likelihood ratio test

Not properly converged

Characteristics of the 4 latent classes are provided in Figure 1. Class 1 (“low disorder symptoms”), which includes just over half of all cases (54%), was below the other classes on symptoms of depression, alcohol use disorder, marijuana use, and nicotine dependence, but was somewhat elevated on anxiety (Mean = 1.26).1 A second latent class (“licit substance use disorder symptoms”) represents 23% of the analysis sample. This class was higher than the low disorder class on symptoms of alcohol use and nicotine dependence, and also somewhat higher on anxiety. A third “mental health disorder symptoms” class (17% of the analysis sample) was elevated on depression and anxiety but lower than all but the low disorder class on alcohol, marijuana, and nicotine disorder and dependence symptoms. Finally, a relatively small class of about 6% of the sample was elevated on all 5 outcome measures. This is called the “comorbid” class because of the apparent co-occurrence of mental health and substance use disorder symptoms for those so classified. The comorbid class was also elevated on marijuana use disorder symptoms.

Figure 1.

Profiles of the adult latent mental health and substance use classes.

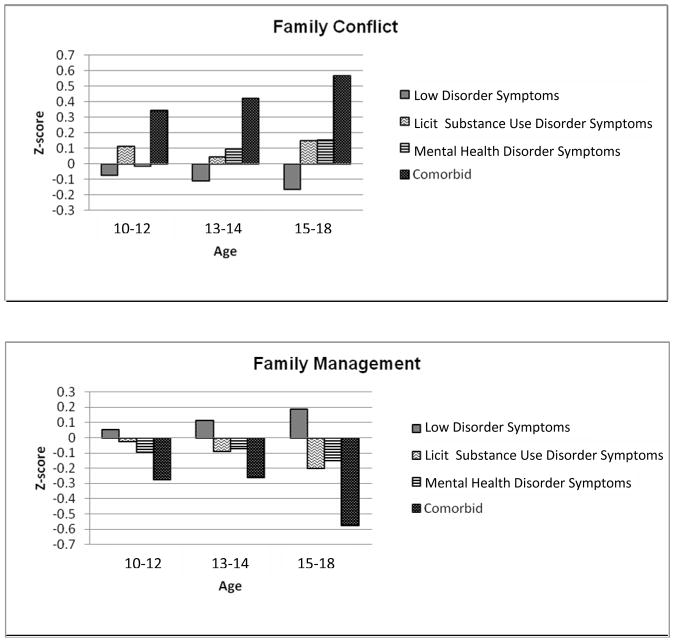

A next step in the analysis was to examine the association between the family predictors and the 4 adult latent classes. Means for each family predictor are shown for each class in Figure 2 (scores are standardized, with an overall mean of 0 at each age). Wald tests compared the scores of each other class with those of the low disorder symptoms class. For family conflict at ages 10–12, the licit substance use disorder symptoms class was marginally significantly higher than the low disorder symptoms class (X2 = 3.31, p - value < .10). Also, the comorbid class was significantly higher than the low disorder symptoms class (X2 = 5.09, p-value < .05). For family conflict at ages 13–14, the licit substance use disorder symptoms class was marginally significantly higher than the low disorder symptoms class (X2 = 2.76, p-value < .10), as was the mental health disorder symptoms class (X2 = 3.82, p-value < .10). The comorbid class was significantly higher than the low disorder symptoms class on family conflict at ages 13–14 (X2 = 7.64, p-value < .01). For family conflict at ages 15–18, the licit substance use disorder symptoms class was significantly higher than the low disorder symptoms class (X2 = 11.6, p-value < .01). This was also true for the mental health disorder symptoms class (X2 = 9.81, p-value < .01) and the comorbid class (X2 = 19.99, p-value < .001).

Figure 2.

Family predictors at ages 10–12, 13–14, and 15–18 and adult mental health and substance use classes.

For proactive family management at ages 10–12, the comorbid class was significantly lower than the low disorder symptoms class (X2 = 4.12, p-value < .05). At ages 13–14, both the licit substance use disorder symptoms (X2 = 4.84, p-value < .05) and comorbid (X2 = 4.2, p-value < .05) classes were significantly lower than the low disorder symptoms class. And at ages 15–18, all classes, including the licit substance use (X2 = 16.25, p-value < .001), mental health (X2 = 9.62, p-value < .01), and comorbid disorder classes (X2 = 20.5, p-value < .001) scored lower than the low disorder symptoms class.

For family involvement at ages 13–14, the licit substance use disorder symptoms class was marginally lower than the low disorder symptoms class (X2 = 2.98, p-value < .10). At ages 15–18, the licit substance use disorder symptoms (X2 = 8.36, p-value < .01), mental health disorder symptoms (X2 = 6.46, p-value < .05), and comorbid (X2 = 7.59, p-value < .01) classes were all significantly lower than the low disorder symptoms class.

Results of the multivariate tests are shown in Tables 2 and 3. Results of Table 2 are for multinomial logistic regressions in which the low disorder symptoms latent class is the reference group. Results of Table 3 are for multinomial logistic regression in which the comorbid latent class is the reference group. As shown in Table 2, at ages 10–12, higher scores on family conflict were associated with increased odds of being in the adult comorbid class (Odds Ratio = 1.76) and the licit substance use disorder symptoms class (Odds Ratio = 1.32) relative the low disorder symptoms class, after controlling for child gender, race/ethnicity, low-income status, childhood delinquency, childhood internalizing behaviors, and early substance use. Higher scores on family conflict were also associated with decreased odds of being in the mental health disorder symptoms class relative to the comorbid class, as shown in Table 3 (Odds Ratio=.52).

Table 2.

Multinomial logistic regression results for predictors at ages 10–12, 13–14, and 15–18: Low disorder symptoms group as reference group

| Mental health and substance use latent classes

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low disordera

|

Licit substance use disorder symptomsa

|

Mental health disorder symptomsa

|

||||

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | Odds ratio | 95% CI | Odds ratio | 95% CI | |

| Ages 10–12 | ||||||

| Family management | 0.99 | (0.70, 1.40) | 1.26 | (0.95, 1.68) | 0.84 | (0.62, 1.14) |

| Family conflict | 1.76 | (1.16, 2.69) | 1.32 | (1.01, 1.72) | 0.92 | (0.69, 1.22) |

| Family involvement | 1.02 | (0.65, 1.58) | 1.01 | (0.77, 1.32) | 0.92 | (0.70, 1.20) |

| Ages 13–14 | ||||||

| Family management | 0.87 | (0.60, 1.26) | 0.88 | (0.67, 1.17) | 0.82 | (0.60, 1.11) |

| Family conflict | 1.92 | (1.22, 3.03) | 1.11 | (0.80, 1.54) | 1.10 | (0.81, 1.49) |

| Family involvement | 1.15 | (0.76, 1.73) | 0.95 | (0.72, 1.24) | 1.21 | (0.91, 1.61) |

| Ages 15–18 | ||||||

| Family management | 0.55 | (0.34, 0.90) | 0.87 | (0.61, 1.26) | 0.78 | (0.55, 1.09) |

| Family conflict | 1.69 | (1.04, 2.74) | 1.41 | (1.01, 1.95) | 1.14 | (0.85, 1.54) |

| Family involvement | 0.96 | (0.62, 1.48) | 0.79 | (0.60, 1.05) | 0.92 | (0.72, 1.18) |

Note

Covariates are gender, race/ethnicity,

low-income, childhood delinquency,

childhood internalizing problems, and early substance use.

Bold = significant at .05 level

Table 3.

Multinomial logistic regression results for predictors at ages 10–12, 13–14, and 15–18: Comorbid group as reference group

| Mental health and substance use latent classes

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low disordera

|

Licit substance use disorder symptomsa

|

Mental health disorder symptomsa

|

||||

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | Odds ratio | 95% CI | Odds ratio | 95% CI | |

| Ages 10–12 | ||||||

| Family management | 1.01 | (0.71, 1.42) | 1.27 | (0.88, 1.84) | 0.85 | (0.55, 1.30) |

| Family conflict | 0.57 | (0.37, 0.86) | 0.75 | (0.48, 1.16) | 0.52 | (0.32, 0.83) |

| Family involvement | 0.98 | (0.63, 1.53) | 0.99 | (0.62, 1.57) | 0.90 | (0.56, 1.46) |

| Ages 13–14 | ||||||

| Family management | 1.15 | (0.79, 1.66) | 1.01 | (0.69, 1.47) | 0.94 | (0.59, 1.49) |

| Family conflict | 0.52 | (0.33, 0.82) | 0.58 | (0.37, 0.90) | 0.57 | (0.35, 0.94) |

| Family involvement | 0.87 | (0.58, 1.31) | 0.83 | (0.54, 1.25) | 1.05 | (0.66, 1.69) |

| Ages 15–18 | ||||||

| Family management | 1.80 | (1.11, 2.92) | 1.58 | (0.94, 2.65) | 1.40 | (0.83, 2.36) |

| Family conflict | 0.59 | (0.36, 0.96) | 0.83 | (0.50, 1.38) | 0.68 | (0.40, 1.15) |

| Family involvement | 1.04 | (0.67, 1.61) | 0.82 | (0.52, 1.30) | 0.96 | (0.60, 1.54) |

Note

Covariates are gender, race/ethnicity,

low-income, childhood delinquency,

childhood internalizing problems, and early substance use.

Bold = significant at .05 level

At ages 13–14, higher scores on family conflict were associated with increased odds of being in the comorbid class relative to the low disorder symptoms class (Odds Ratio = 1.92). Higher scores on family conflict were also associated with decreased odds of being in the licit substance use disorder symptoms class (Odds Ratio = .58) and mental health disorder symptoms class (Odds Ratio = .57), relative to the comorbid class.

Results for the same predictors at ages 15–18, also shown in Tables 2 and 3, indicate that adjusted scores for family conflict were associated with increased odds of being in the comorbid class (Odds Ratio = 1.69) and the licit substance use disorder symptoms class (Odds Ratio = 1.41), relative to the low disorder symptoms class. Additionally, higher scores for family management at ages 15–18 were associated with significantly lower odds of being in the comorbid class relative to the low disorder class (Odds Ratio = .55).

DISCUSSION

Multivariate analysis results indicate that family conflict – regardless of when in development (throughout adolescence) – is an important factor distinguishing those whose adult lives are characterized by mental health and substance use problems. Additionally, higher scores for family management in late adolescence distinguished those with less disorder in adulthood. Results, thus, suggest that family influences of at least these 2 forms are predictive of later emerging problems in adulthood. Interestingly, family involvement, characterized by proosocial activities of parents and children together, did not emerge here as a strong or consistent predictor of the adult classes.

Findings have important implications for prevention practice. There is evidence that preventive interventions focused on helping caregivers improve their parenting skills can significantly lessen risks and improve the quality of the home environment, thereby promoting positive youth development [1, 38]. In that family conflict emerged as a consistent factor distinguishing those with multiple disorder symptoms in adulthood from those with fewer symptoms, it is important that interventions throughout childhood and adolescence focus first and foremost on reducing hostility among family members and replacing negative patterns of interaction (e.g., yelling and arguing) with those of a more positive quality. Exemplar programs are reviewed and discussed elsewhere [39].

Limitations of the study include our having relied on existing data, which contain some, but not all relevant indicators of the family predictors of primary interest. While indicator variables are limited to some extent by the data available to us in the larger study, the items in each wave were carefully selected for each predictor. Additionally, the method of analysis, while suited to the goals of the study, did not allow us to account for correlations among the same predictors measured over time. The study is also limited by our having focused exclusively on the family as a context for prevention, thereby ignoring other domains and settings in which prevention efforts could be situated, such as the peer groups, schools, and communities. It is important that future research attend to these domains in predictive modeling and prevention planning. Additionally, theory-informed tests of mediators and moderators of family risk influences could strengthen theory and help reduce the number of young adults who experience mental health and substance use disorders.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants #5R01DA021426-11 and #1R01DA09679-14 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of these funders.

Footnotes

In this class, all the mental health and substance use indicators except anxiety were almost 0. For anxiety, those in this particular class had fewer anxiety symptoms than the study sample as a whole (Mean = 1.97). In addition, fewer anxiety symptoms were reported by those in this class compared to the other 3 classes.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Herrenkohl TI, Sousa C, Tajima EA, Herrenkohl RC, Moylan CA. Intersection of child abuse and children’s exposure to domestic violence. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2008;9:84–99. doi: 10.1177/1524838008314797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Middlebrooks JS, Audage NC. The effects of childhood stress on health across the lifespan. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrenkohl TI, Kosterman R, Mason WA, et al. Effects of childhood conduct problems and family adversity on health, health behaviors, and service use in early adulthood: Tests of developmental pathways involving adolescent risk taking and depression. Dev Psychopathol. 2010;22:655–65. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dodge KA, Greenberg MT, Malone PS. Testing an idealized dynamic cascade model of the development of serious violence in adolescence. Child Dev. 2008;76:1907–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrenkohl TI, Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, Mason WA. Effects of growth in family conflict in adolescence on adult depressive symptoms: Mediating and moderating effects of stress and school bonding. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:146–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reinherz HZ, Paradis AD, Giaconia RM, Stashwick CK, Fitzmaurice G. Childhood and adolescent predictors of major depression in the transition to adulthood. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:2141–47. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amato PR, Sobolewski JT. The effects of divorce and marital discord on adult children’s psychological well-being. Am Sociol Rev. 2001;66:900–21. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paradis AD, Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM, et al. Long-term impact of family arguments and physical violence on adult functioning at age 30 years: Findings from the Simmons Longitudinal Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:291–99. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181948fdd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nomura Y, Wickramaratne PJ, Warner V, Mufson L, Weissman MM. Family discord, parental depression, and psychopathology in offspring: Ten-year follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:402–09. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200204000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arria AM, Kuhn V, Caldeira KM, et al. High school drinking mediates the relationship between parental monitoring and college drinking: A longitudinal analysis. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2008;3(6) doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo J, Hawkins JD, Hill KG, Abbott RD. Childhood and adolescent predictors of alcohol abuse and dependence in young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:754–62. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turley RNL, Desmond M, Bruch SK. Unanticipated educational consequences of a positive parent-child relationship. J Marriage Fam. 2010;72:1377–90. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:247–57. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grant BF, Harford TC. Comorbidity between DSN-IV alcohol-use disorders and major depression: Results of a national survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;39:197–206. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JO, Herrenkohl TI, Kosterman R, Small CM, Hawkins JD. Unpublished manuscript. 2011. Social disparity in the co-occurrence of mental health and substance use problems and its adult socioeconomic consequences. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF. Preventing adolescent health-risk behaviors by strengthening protection during childhood. Arch Pediatrics Adolesc Med. 1999;153:226–34. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellickson PL, Bell RM. Drug prevention in junior high: A multi-site longitudinal test. Science. 1990;247:1299–305. doi: 10.1126/science.2180065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thornberry TP, Lizotte AJ, Krohn MD, Farnworth M. The Role of Delinquent Peers in the Initiation of Delinquent Behavior. Albany, NY: University at Albany Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawkins JD, Kosterman R, Catalano RF, Hill KG, Abbott RD. Promoting positive adult functioning through social development intervention in childhood: Long-term effects from the Seattle Social Development Project. Arch Pediatrics Adolesc Med. 2005;159:25–31. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaffee SR, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, et al. Differences in early childhood risk factors for juvenile-onset and adult-onset depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;50:215–22. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newman DL, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, et al. Psychiatric disorder in a birth cohort of young adults: Prevalence, comorbidity, clinical significance, and new case incidence from ages 11 to 21. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:552–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM, Carmola Hauf AM, Wasserman MS, Paradis AD. General and specific childhood risk factors for depression and drug disorders by early adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:223–31. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200002000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, Mason WA, et al. Assessment of behavior problems in childhood and adolescence as predictors of early adult depression. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;32:118–27. doi: 10.1007/s10862-009-9138-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mason WA, Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, et al. Predicting depression, social phobia, and violence in early adulthood from childhood behavior problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:307–15. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200403000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Achenbach TM. Teacher’s Report Form. Burlington, VT: Center for Children, Youth and Families, University of Vermont; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent class and latent transition analysis. Hoboken; New Jersey: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hagenaars JA, McCutcheon AL. Applied latent class analysis. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. MPlus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tofighi D, Enders CK. Identifying the correct number of classes in a growth mixture model. In: Hancock GR, editor. Mixture models in latent variable research. Greenwich, CT: Information Age; 2007. pp. 317–41. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muthen B, Muthen LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism Jun. 2000;24:882–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthen BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling A Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Equation Model. 2007;14:535–69. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Celeux G, Soromenho G. An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. J Classif. 1996;13:195–212. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clark S, Muthen B. Relating latent class analysis results to variables not included in the analysis. MPlus. 2010 Feb 18; Available at: http://www.statmodel.com/papers.shtml.

- 35.Acock AC. Working with missing values. J Marriage Fam. 2005 Nov;67:1012–28. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buhi ER, Goodson P, Neilands TB. Out of sight, not out of mind: strategies for handling missing data. Am J Health Behav. 2008 Jan-Feb;32:83–92. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:147–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Institute of Medicine. Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for prevention intervention research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jenson JM. Advances and challenges in the prevention of youth violence. In: Herrenkohl TI, Aisenberg E, Williams JH, Jenson JM, editors. Violence in context: Current evidence on risk, protection, and prevention. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 111–29. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raftery AE. Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociol Methodol. 1995;25:111–63. [Google Scholar]