Abstract

Axonal insult induces retinal ganglion cell (RGC) death through a BAX-dependent process. The pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member BIM is known to induce BAX activation. BIM expression increased in RGCs after axonal injury and its induction was dependent on JUN. Partial and complete Bim deficiency delayed RGC death after mechanical optic nerve injury. However, in a mouse model of glaucoma, DBA/2J mice, Bim deficiency did not prevent RGC death in eyes with severe optic nerve degeneration. In a subset of DBA/2J mice, Bim deficiency altered disease progression resulting in less severe nerve damage. Bim deficient mice exhibited altered optic nerve head morphology and significantly lessened intraocular pressure elevation. Thus, a decrease in axonal degeneration in Bim deficient DBA/2J mice may not be caused by a direct role of Bim in RGCs. These data suggest that BIM has multiple roles in glaucoma pathophysiology, potentially affecting susceptibility to glaucoma through several mechanisms.

BAX is a critical mediator of neuronal cell death. In the retina, Bax deficiency protects against developmental apoptosis of many retinal cells, including, retinal ganglion cells (RGCs)1,2,3,4,5. BAX is also an important mediator of RGC loss after axonal insult. BAX is up-regulated in response to optic nerve injury6 and its suppression rescues RGC somas from death after mechanical optic nerve injury2,3,7. Bax was also shown to be required for RGC death in an animal model of glaucoma3, a common neurodegeneration where elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) ultimately leads to an RGC axonal insult8,9,10,11. Importantly, other apoptotic or non-apoptotic pathways do not circumvent the long-term protection provided by Bax deficiency3,7. Thus, BAX is major mediator of RGC death in disease. The funneling of cell death pathway(s) to a central point in glaucoma–BAX activation–provides a powerful starting point for unraveling the complex process that determines RGC survival in glaucoma.

BAX is a member of the Bcl-2 family of proteins12. Direct interactions between different family members (both pro-survival and pro-death family members) determine the likelihood of BAX activation in a cell. BH3-only proteins are pro-death Bcl-2 family members that trigger cell death through BAX activation. After injury, activation of different BH3-only proteins occurs in an insult and context-specific manner12. For example, BBC3 is required for BAX activation in developing RGCs, but does not play a primary role in regulating RGC death after axonal injury1. In fact, it is unknown which BH3-only proteins, if any, are required for RGC death after axonal injury and in glaucoma. The BH3-only protein BIM is a good candidate for activating BAX in axonally-injured RGCs. After optic nerve injury, Bim transcription increases in the retina and BIM is detected in the RGC layer6,13,14. In addition, an ex vivo study demonstrates a pro-apoptotic function for BIM early after axonal insult13. However, it is unknown if BIM is required for RGC death after axonal injury in vivo or if its role varies based on the type of axonal insult. The importance of BIM was tested in vivo after optic nerve crush and in glaucoma and, unlike BAX, BIM is not required for RGC death in these models. Surprisingly, BIM was found to have multiple functions, both intrinsic and extrinsic to RGCs, relevant to glaucoma pathophysiology.

Results

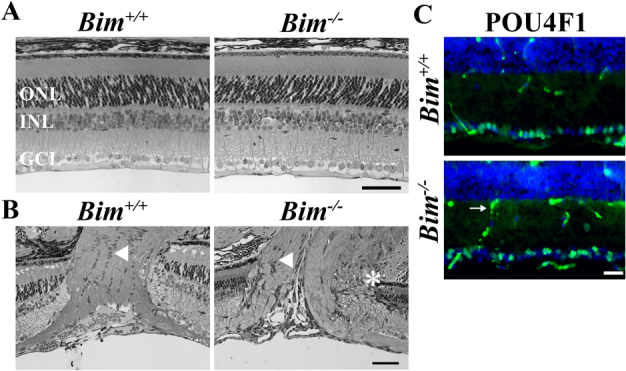

BIM plays several roles in retinal morphogenesis

BIM is expressed in the developing retina15, suggesting that it may regulate normal retinal developmental cell death. As previously reported1,16,17, Bim deficiency does not grossly affect retinal neuronal patterning (Fig. 1A). BIM is known to be critical for retinal vasculature remodeling and deficiency in Bim does increase the amount of retinal vasculature (17and data not shown). In contrast to the retina, the optic nerve head of B6.Bim-/- mice had significant morphological abnormalities (Fig. 1B). In 5 out of 5 B6.Bim deficient retinas there were clear abnormalities in the retinal-optic nerve head boundary. Also, the arrangement of glial cells just behind the retina in the optic nerve, the glial lamina cribrosa in mice, appeared less well organized than in wild-type mice. Thus, Bim deficiency alters morphology of the retina in several ways that could be important in retinal disease, increasing retinal vasculature and causing optic nerve head dysmorphogenesis.

Figure 1. Bim deficiency affects retinal development.

(A) Retinal sections from Bim+/+ and Bim-/- mice confirms previous reports1,17 that Bim deficiency did not alter the gross organization of number of retinal neurons. (B) Bim deficiency caused dysmorphogenesis of the optic nerve. In Bim deficient mice the retinal-optic nerve head border is abnormal, with apparent retinal neuronal layers entering the optic nerve head (asterisk). Also the normal arrangement of glia cell bodies does not appear to be present in the area of the lamina cribrosa (arrowhead). (C) However, optic nerve head morphology changes did not affect the number of RGCs, as judged by POU4F1 (BRN3A, green) expression, which is specifically expressed in 80% of RGCs in the retina19. Note, the secondary antibody also detects retinal vasculature (arrow). DAPI, blue; ONL, outer nuclear layer; INL inner nuclear layer, GCL, ganglion cell layer; scale bar, A,B = 50 μm, C = 25 μm.

Using RGC layer thickness measurements Doonan and colleagues16 reported that Bim deficiency delayed developmental RGC death, but had no effect on the final number of RGCs. There are several mouse mutants where there is a small, but significant increase in RGC number (e.g.1,18). It is unlikely that this level of increase would be detectable by measuring RGC layer thickness, which is generally a single layer of cells thick. Therefore to determine BIM’s impact on the final number of RGCs in the mouse retina, POU4F1 (BRN3A) positive cells were counted in sections from the central retina. Bim deficiency did not alter the number of RGCs surviving in the adult (Fig 1C; as judged by POU4F1 expression, which is specifically expressed in 80% of RGCs in the retina19; POU4F1+ cells per mm ± SEM: Bim+/+ 58±5, Bim+/- 61±4, Bim-/- 56±3; P = 0.69; n = 4 for each genotype).

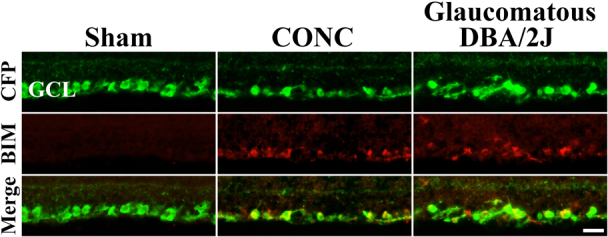

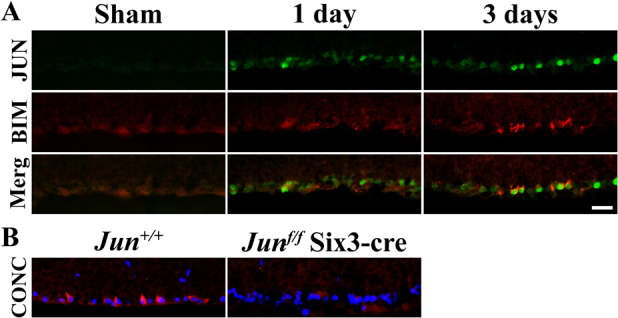

BIM is expressed in RGCs after axonal injury

RGC death after axonal injury is an apoptotic and BAX-dependent process1,2,3,7. Unlike in BAX-dependent RGC developmental cell death1, no specific BH3-only protein is known to be similarly required after axonal injury. BIM is a primary candidate to activate BAX after RGC axonal injury because the loss of BIM protects RGCs in retinal explant cultures for up to four days13. Therefore, BIM expression was examined following mechanical axonal injury, controlled optic nerve crush (CONC) and in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. In unmanipulated retinas BIM was not detected in the RGC layer (Fig. 2). Using mice that express CFP predominately in RGCs20,21, BIM was shown to be expressed in RGCs by the time RGCs begin to die after CONC. BIM was also expressed in RGCs in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice (10 months of age; Fig. 2). Thus, the expression pattern of BIM is consistent with a role in axonal-injury induced RGC death.

Figure 2. BIM is expressed in RGCs after axonal injury.

In young uninjured RGCs (Sham), BIM is not detected in RGCs. RGCs are marked genetically with CFP using B6.Thy1-CFP mice. In these mice 95% of RGCs express CFP and only a small percent of the other type of neurons in the ganglion cell layer, displaced amacrine cells, express the transgene20,21. At the beginning of RGC death after CONC (3 days after injury) BIM colocalizes with the vast majority of CFP+ cells. BIM continues to be expressed in the RGC layer at 5 days and 7 days indicating it is expressed throughout the time when RGC death peaks. In glaucomatous DBA/2J mice, BIM is also expressed in RGCs (RGCs are also marked with the Thy1-CFP transgene; backcrossed into DBA/2J mice >20 times). BIM expression was not detected in all sections, but was present in RGCs in 4 out of 6 retinas examined. This expression is consistent with the asynchrony of DBA/2J glaucoma, with only some 10 month old animals undergoing active RGC loss29. Also, in diseased retinas, BIM was not detected in every section likely reflecting the naturally-occurring sectorial pattern of RGC loss8. In addition, BIM expression was absent in 10 month old D2.Gpnmb mice (data not shown; D2.Gpnmb mice are a control strain of D2 mice that are wild-type for one of the genes that causes the iris disease and do not develop elevated IOP40,44). The lack of BIM expression in D2.Gpnmb RGCs indicates that change in BIM expression in DBA/2J RGCs is caused by the glaucomatous insult and not age or genetic background. These data show that BIM is expressed in axonally injured RGCs. Scale bar, 25 μm.

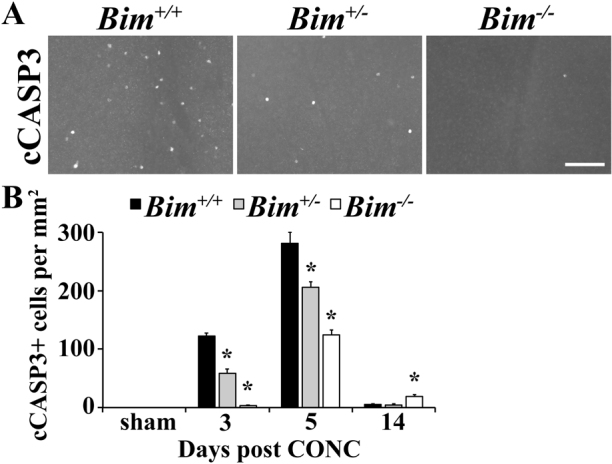

Bim deficiency reduces CASP3 activation after mechanical optic nerve injury

McKernan et al.13 showed that Bim deficiency could protect RGCs in explant cultures for at least 4 days (the longest time in culture examined). Explanting a retina likely involves numerous retinal injuries, but an important one for RGCs is axotomy. However only a small percentage of RGCs die 4 days after axonal injury in vivo and the loss of RGCs can continue for several weeks1,22,23; so whether BIM is critical for RGC death after optic nerve injury is unclear. If BIM is required for BAX-dependent RGC death, then axonally injured RGCs in Bim nulls should not undergo apoptosis and survive for months as observed in Bax deficient mice2,3,7. To determine the role of BIM in RGC death after axonal injury in vivo, CONC was performed on Bim+/+, Bim+/- and Bim-/- mice (Fig 3). Counts of activated (cleaved) caspase 3 positive cells (cCASP3+) in the RGC layer of retinal flat mounts were used to identify apoptotic RGCs. At the beginning of RGC death after CONC, 3 days following injury, the complete absence of BIM drastically lessens cell death (Fig. 3; P<0.001). By 5 days, cCASP3 was observed in Bim null retinas, although the number of cCASP3+ cells was still significantly less than in wild-type retinas (P<0.001). Interestingly, at 14 days after CONC, Bim-/- mice have significantly more dying cells than Bim+/+ suggesting that Bim deficiency only delays cell death (P = 0.01). Bim transcription is known to be involved in its induction after cell death stimuli and heterozygosity for a Bim null allele can reduce death in neurons after injury24,25. Consistent with this effect, the loss of one allele of Bim also delays CASP3 activation both 3 and 5 days after CONC (Fig. 3, P<0.001). Thus, BIM is an important early pro-apoptotic factor in RGC death after axonal injury.

Figure 3. Bim deficiency delays RGC death after CONC.

(A) RGC death, as judged by presence of cleaved caspase 3 (cCASP3+), was clearly decreased in both Bim+/- and Bim-/- mice 3 days after injury (the onset of cell death). (B) Quantification of cCASP3+ cells shows that there is a significant decrease (*, P<0.01) in cell death in both Bim+/- and Bim-/- mice at 3 and 5 days after injury. Interestingly, 14 days after injury, when about 50% of RGCs are lost, cell death is increased in the Bim-/- mice compared to the other genotypes (cCASP3+ cells per mm2: Bim+/+ 6±1; Bim-/- 19±3; P = 0.01). N≥6 for each genotype and time point; scale bar, 100 μm.

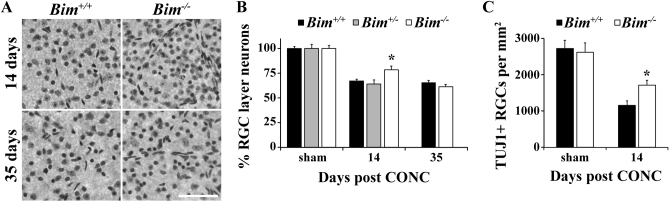

Bim deficiency delays RGC death after mechanical optic nerve injury

Nissl stained RGC layer neurons were counted at 14 and 35 days after CONC in order to assess long term RGC survival in Bim+/+ and Bim-/- mice (Fig. 4A,B). 14 days post injury all genotypes had lost a significant number of RGC layer neurons compared unmanipulated retinas (Fig 4B, P<0.001). Thus, BIM is not required for RGC death after axonal injury. However, Bim-/- retinas had significantly more surviving RGC layer neurons than injured wild-type retinas at 14 days post injury (Fig 4B; P<0.001). The protection of RGCs in Bim-/- mice at 14 days after injury was confirmed by counting RGCs using TUJ126 as a marker (Fig. 4C; P<0.001). By 35 days, when RGC death after CONC is nearly complete, the number of surviving RGC layer neurons is similar between Bim+/+ and Bim-/- retinas (Fig. 4B). Although BIM plays an early role in axonal injury induced death of RGCs, the loss of RGCs still occurs in the absence of BIM.

Figure 4. Bim deficiency increases RGC survival after CONC.

(A,B) To determine if Bim deficiency increases RGC survival after CONC, counts of Nissl stained ganglion cell layer neurons were performed. Note, only RGCs die after CONC and approximately half of RGC layer neurons are amacrine cells32, so a loss of 50% of RGC layer neurons equals complete RGC loss. All genotypes had a significant cell loss compared to sham retinas at 14 days after CONC (P<0.001). Consistent with the decrease in cCASP3+ cell counts, there was a significantly increase in the number of RGC layer neurons at 14 days after injury in Bim-/- mice (*, P<0.001, compared to Bim+/+ mice). However, by 35 days after injury, Bim deficiency did not provide protection. Note, since Bim+/+ and Bim+/- mice had similar loss of RGC layer neurons at 14 days, Bim+/- retinas were not assessed at 35 days. (C) RGC counts, using the RGC marker TUJ126, confirmed the increased survival of RGCs 14 days after axonal injury (*, P<0.001). N≥5 for all genotypes and ages except n = 3 for Bim+/-; scale bar, 100 μm.

JUN regulates BIM expression in RGCs after axonal injury

JUN has been shown to be a major regulator of RGC death after axonal injury27 and is known to regulate Bim28. Prior to cell death, RGCs expressing JUN display perinuclear BIM expression (Fig 5A). To determine if JUN controls BIM expression in RGCs, BIM expression was assessed in Jun deficient retinas (Junfl/fl Six3-cre+) after CONC. In the absence of Jun, BIM could not be detected in RGCs (Fig. 5B) at 3 days or 7 days after injury, suggesting that in RGCs, Bim is a downstream target of activated JUN.

Figure 5. JUN controls BIM expression after axonal injury.

(A) JUN, which is known to control RGC death after CONC, is expressed by one day after injury, prior to BIM expression. By 3 days after CONC, RGCs coexpress JUN and BIM. (B) In contrast to the robust BIM expression (red) seen after CONC in RGCs of Jun+/+ mice, there is no BIM expression in Jun deficient RGCs (Junf/f; Six3-cre). Thus, JUN appears to control BIM expression after axonal injury. Similar results were obtained from at least 3 different mice for each time point and genotype. DAPI, blue; Scale bar, 25 μm.

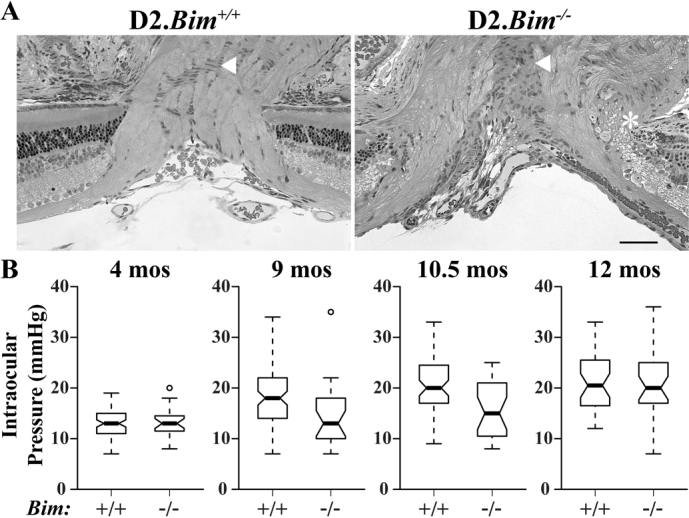

Bim deficiency alters glaucoma relevant morphology and ocular hypertension in DBA/2J mice

DBA/2J mice develop an iris disease that leads to ocular hypertension and RGC death in most mice by one year of age29,30,31. To test the importance of BIM in glaucomatous neurodegeneration a null allele of Bim was backcrossed for 10 generations into the DBA/2J genetic background (D2.Bim-; all mice used for the glaucoma studies, including D2.Bim+/? and D2.Bim-/-mice, were from this segregating line). Since the optic nerve head is thought to be a key initial site of injury8,9,10,11, alteration in its morphology could have an effect on glaucoma progression. As with B6.Bim-/- mice (Fig. 1B), ocular nerve head morphology was abnormal in young D2.Bim-/- eyes (3-5 months of age; prior to pigment disease and IOP elevation). Similar to B6.Bim-/- optic nerve heads, in all 5 D2.Bim-/- eyes examined there was a disruption of the border between the retina and the optic nerve (Fig 6A). Also, the cellular arrangement of the glial lamina region appeared disrupted. Thus, the loss of BIM during development may alter optic nerve head dynamics during a glaucomatous insult.

Figure 6. Bim deficiency alters glaucomatous insult in DBA/2J mice.

To test importance of BIM in glaucomatous RGC death, a null allele of Bim was backcrossed into DBA/2J for at least 10 generations (D2.Bim-). The optic nerve head is the likely location of an important glaucomatous insult. (A) Since the optic nerve head was abnormal in B6.Bim-/- eyes we examined optic nerve head morphology in D2.Bim-/- mice. In 5 out of 5 D2.Bim-/- optic nerve heads examined there were clear abnormalities similar to those seen in B6.Bim-/-. Most notably there were abnormal retinal optic nerve head borders (asterisk) and the gross arrangement of the glial cells in the area of the glial lamina (arrow) was poorly organized. Thus, it is possible that in D2.Bim-/- mice the changes in optic nerve head morphology alter the susceptibility of D2.Bim-/-to ocular hypertension induced neuronal injury. (B) The IOP profile of D2.Bim+/+ mice was similar to previous reports29. At 9, 10.5 and 12 months of age IOP was significantly elevated compared to younger mice (P<0.001 for each age). The IOP in 4 month old D2.Bim-/- mice was not different to young D2.Bim+/+ mice (P = 0.68). There was also no significant increase in IOP in D2.Bim-/- mice at 9 or 10.5 months of age. IOP was significantly increased in D2.Bim-/- at 12 months of age (P<0.001). Thus, Bim deficiency appears to delay, but not prevent IOP elevation in DBA/2J mice. N≥24 for all ages and genotypes. Scale bar, 50 μm.

DBA/2J mice develop an iris pigment dispersion syndrome with age that eventually causes ocular hypertension. Consistent with other studies using DBA/2J mice, prior to the iris disease D2.Bim+/+ mice had an average IOP of 13.0±0.3 mmHg (4 months of age; Fig 6B). The IOP of D2.Bim+/- mice were not significantly different than for wild-type DBA/2J mice at any time point examined, and D2.Bim+/+ mice and D2.Bim+/- mice were used as controls (referred to as D2.Bim+/? mice). The IOP of D2.Bim+/? mice increased with age, similar to previous reports. IOP was significantly elevated at 9, 10.5 and 12 months of age (Fig. 6B; 9 months, 18.9±0.7 mmHg; 10.5 months, 20.4±0.7 mmHg; 12 months, 20.9±0.9 mmHg; P<0.001 for all genotypes). Prior to the onset of iris disease, D2.Bim-/- mice had normal IOPs (13.3±0.6 mmHg, P = 0.68), suggesting BIM does not have a role in the regulation of IOP under normal physiological conditions. In contrast to D2.Bim+/?, IOP was not significantly elevated in D2.Bim-/- at either 9 or 10.5 months of age (Fig. 6B; 9 months, 14.3±1.3 mmHg, P = 0.49; 10.5 months, 15.4±1.0 mmHg, P = 0.10). However, individual D2.Bim-/- eyes did have elevated IOPs at both of these time points (Fig. 6B). By 12 months of age IOP was significantly elevated in D2.Bim-/- compared to young mice of the same genotype (20.3±1.3 mmHg, P<0.001). The IOP profile of D2.Bim-/- mice was similar to that observed in D2.Bax-/- mice3. Clinical examination of the anterior segment suggested the iris disease was not altered in D2.Bax-/- mice3. Gross examination of the anterior segment of D2.Bim-/- mice suggested there was no alteration of the iris pigment dispersion disease, though the anterior segment phenotype was not assessed in detail. Thus, there may be a loss of cells involved in IOP regulation in pigmentary glaucoma that occurs through an apoptotic process regulated by BIM and BAX.

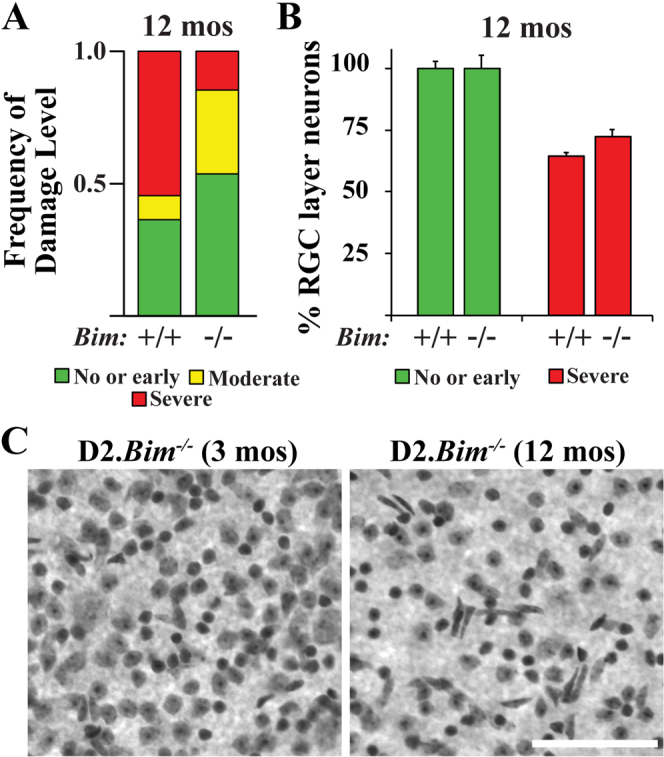

BIM is not required for a glaucomatous neurodegeneration

Lower IOP delays but does not prevent optic nerve degeneration in D2.Bax-/- mice. In order to determine the extent of glaucoma in D2.Bim-/- mice, optic nerve degeneration was assessed using a validated optic nerve damage grading scale3,8,29. Optic nerve damage was categorized as no or early, moderate, or severe depending on the amount of axon loss and gliosis. Not all DBA/2J eyes develop glaucoma; however, by 12 months of age a majority of DBA/2J eyes will have severely degenerated optic nerves. As expected, in D2.Bim+/? 17 out of 28 (61%) nerves had severe degeneration (Fig. 7A). Bim deficiency did significantly lessen the amount of optic nerve damage at 12 months of age (P<0.001) with only 6 out of 41 (15%) D2.Bim-/- nerves graded as severe. There was a corresponding increase in moderate nerves in D2.Bim-/-, suggesting that axonal injury in D2.Bim-/- mice is reduced, corresponding to the delay in IOP elevation.

Figure 7. BIM is not required for RGC death in glaucoma.

(A) As judged by a validated grading scale of optic nerve damage29, the distribution of optic nerve damage in D2.Bim-/- mice was significantly different to D2.Bim+/+ (P<0.001) at 12 months of age. D2.Bim+/? (wild-type and heterozygous mice were included in the analysis; no difference in optic nerve degeneration was noted between the genotypes) had a similar profile of optic nerve damage to previous reports3,8,29: 33 nerves assessed with 36% no or early, 9% moderate, 55% severe. In contrast in D2.Bim-/- eyes there were far fewer nerves judged to have severe optic nerve damage (41 nerves assessed, 53% no or early, 32% moderate, 15% severe). (B) To determine if Bim deficiency protected RGC somas after glaucomatous injury ganglion cell layer neurons were counted in D2.Bim+/+ and D2.Bim-/- eyes. For both genotypes, eyes with corresponding optic nerves judged either without damage (no or early) or severe were counted. Note, only RGCs die in DBA/2J glaucoma35 and approximately half of RGC layer neurons are amacrine cells32,34, so a loss of 50% of ganglion cell layer neurons equals complete RGC loss. Bim deficiency did not prevent somal loss in glaucoma. N≥5 for both genotypes and grades. Scale bar, 100 μm.

In DBA/2J mice it appears that axonal degeneration precedes somal apoptosis3,8,11. RGC somal degeneration but not axonal degeneration is dependent on BAX in DBA/2J glaucoma3. Since some D2.Bim-/- mice did develop severe optic nerve degeneration, it was possible to determine if BIM is required to induce somal degeneration in DBA/2J glaucoma. Total RGC layer neurons were counted in 12 month D2.Bim+/? and D2.Bim-/- eyes either with severe optic nerve damage or no obvious glaucomatous damage (no or early nerves). There was significant loss of RGC layer neurons in D2.Bim-/- retinas when the optic nerves had severe degeneration (Fig. 7B; 72±6%; P<0.001). This loss in RGC layer neurons was slightly less than that observed in D2.Bim+/? eyes (64±3%), but this difference was not significant (P = 0.21). Since the RGC layer consists of similar numbers of RGCs and amacrine cells2,32,33,34 and only RGCs die in DBA/2J glaucoma35, the glaucomatous eyes examined in D2.Bim+/? and D2.Bim-/- mice both had massive RGC loss.

Discussion

Glaucoma is a complex disease with the ultimate cause of blindness being the death of RGCs. Axonal injury in the lamina cribrosa, a specialized structure that RGC axons pass through as they exit the eye, is thought to be the critical insult for RGCs8,9,10,11. Axonal insult induced RGC somal degeneration is BAX dependent2,3,7, but the molecules that control BAX activation are undefined. BH3-only proteins are pro-death Bcl-2 family members that help control BAX activation12. A likely candidate for activating BAX after axonal injury is the BH3-only protein BIM. Using Bim knockout mice we sought to determine if BIM was critical for BAX activation (RGC death) after axonal injury, including in a mouse glaucoma model.

Complete deficiency or heterozygosity for a null allele of Bax prevents RGC death even after extensive time after optic nerve crush injury and in glaucoma3,7. These data suggest that the levels of BAX, and subsequently activated BAX, are critical in determining RGC somal death. BAX activation is dependent on the level of BH3-only proteins, particularly those, like BIM, BID and BBC3, that can directly activate BAX36,37. A single member, BBC3, is required for the normal developmental death of RGCs, however, Bbc3 deficiency only provided a minor delay in RGC death after axonal injury1. BIM has been shown to be involved in neuronal death during development and after injury13,24,28,38. In fact in a retinal explant model, where RGCs are injured by axotomy and likely other insults, Bim deficiency completely prevented RGC death for up to 4 days in culture13. This result implicates BIM as an important factor controlling RGC death after injury. Due to limitations of the explant model it can only assess the earliest time points of cell loss after axonal injury, which is just beginning in vivo at 3 days and occurs over at least 3 weeks1,22. In vivo, Bim deficiency significantly decreased RGC death after axonal injury at 3 days. However, by 5 days after injury there was substantial RGC death, though this death was also significantly reduced compared to Bim+/+ mice. The loss of BIM did have a corresponding minor effect on RGC survival at later time points, but did not provide significant and complete protection as observed in Bax deficient mice after extensive time. Thus, it appears that the absence of BIM mainly affects the rate of death after axonal injury, but not the ultimate survival of RGCs.

The fact that single deficiency in Bim and to a far lesser extent Bbc31 only delay death suggests that other factors contribute to RGC death after axonal injury. The expression of BID, the other BH3-only protein that is capable of directly activating BAX, is consistent with a role in RGC death after axonal injury39. However, we have found that Bid deficiency does not delay or prevent RGC death after axonal injury (unpublished observation). It is unclear if these molecules work in combination or if indirect or non-canonical BAX activation can occur after axonal injury. Interestingly, we recently showed that the transcription factor JUN was a key mediator of RGC death after axonal injury27. JUN activation appears to be upstream of BIM (Fig. 5). Jun deficiency provided a far more extensive protection of RGCs than Bim deficiency27, suggesting that other downstream targets of JUN activation are important mediators of BAX activation after axonal injury. Identifying additional targets of JUN will help to determine if BAX activation is completely dependent on pro-death Bcl-2 family members or whether alternative pathways are involved.

DBA/2J mice develop elevated IOP subsequent to an iris disease that is similar to pigment dispersion syndrome in humans29,40,41. It is possible that cell death may play a role in the iris disease or in the viability of trabecular meshwork cells (the cells primarily responsible for regulating IOP in the iridocorneal angle) in response to an insult. The significant lessening of IOP elevation (glaucomatous insult) in D2.Bim-/- mice was similar to that observed in D2.Bax-/- mice. Lessening IOP elevation is not seen in many of the other genetic or therapeutic manipulations that effect RGC neurodegeneration in DBA/2J mice (e.g.42,43,44,45,46,47). In D2.Bax-/- mice there were no changes in the clinical presentation of the iris disease, suggesting that Bax deficiency was affecting IOP regulation and not the iris disease. Loss of trabecular meshwork cells has been linked to IOP elevation in humans48,49,50,51 and mice52. In humans, pigment dispersion syndrome only leads to pathological ocular hypertension (pigmentary glaucoma) and RGC loss in a subset of patients41. Why some patients are susceptible to IOP elevation is unknown. It is possible that this susceptibility results from the variability of the pigmentary insult causing death of trabecular meshwork cells. Our data suggests that a component of IOP elevation in pigment dispersion patients involves a BIM-BAX dependent cell death process. It will be important to test the role of BIM directly in trabecular meshwork cells and determine if a BIM dependent pathway can induce trabecular meshwork cell death. Manipulating this pathway may be a method of preventing IOP elevation in pigment dispersion syndrome and other ocular hypertensive diseases.

The lessening of IOP elevation in D2.Bim-/- mice may not completely explain the large protection from optic nerve degeneration conferred by Bim deficiency. The IOP profile of D2.Bim-/- mice was similar to that observed in D2.Bax-/- but the protection from glaucomatous optic nerve degeneration was far greater in D2.Bim-/- mice. Bim deficiency caused several abnormalities with retinal development that could contribute to the protection. Normal developmental retinal vasculature remodeling is disrupted in Bim deficient mice17 leading to a significant increase in the amount of vasculature. Recently, work has implicated the vasculature as important unit in neurodegenerative disease, including glaucoma45,53. It is possible that extra retinal vasculature directly or indirectly alters the way the retina responds to IOP elevation. Finally, optic nerve morphogenesis was disrupted in Bim deficient mice. There was a clear lack of arrangement of glia in the area of the lamina cribrosa and abnormalities in the retina-optic nerve border and D2.Bim-/- mice. Interestingly, optic nerve morphology has been suggested to be an endophenotype for glaucoma54,55. This is perhaps not surprising since the lamina cribrosa is thought to be a key structure in many aspects of glaucoma and it is certainly plausible that alterations in its morphology change RGC susceptibility to IOP elevation. Thus, there are several roles for BIM in ocular development that may alter susceptibility to ocular hypertension.

Bim deficiency significantly reduced the number of eyes that had severe glaucoma, as judged by optic nerve degeneration. However, 15% of D2.Bim-/- eyes developed severe optic nerve degeneration. These degenerated nerves allowed us to test whether BIM was required for RGC death in glaucoma. Unlike in Bax deficient mutants, RGCs were lost in D2.Bim-/- eyes with severe glaucomatous optic nerve degeneration. Even though BIM is expressed in glaucomatous RGCs and plays a role in axonal injury induced neuronal death, BIM is not required for BAX activation and RGC death in glaucoma.

It appears that BIM plays several roles in ocular development and disease that could directly affect glaucoma pathophysiology. During retinal development BIM is critical for normal retinal vasculature development17 and optic nerve head morphogenesis, both of which have been implicated as endophenotypes in glaucoma. Bim deficiency also lessened/delayed IOP elevation in DBA/2J mice, suggesting BIM might regulate trabecular meshwork cell death after insult. Finally, Bim deficiency delayed RGC death after axonal injury, but did not prevent RGC death after a glaucomatous insult. In the future it will be important to uniquely manipulate BIM expression in each of the tissues where BIM has a role in ocular physiology and pathophysiology to gain a better understanding of its role in ocular hypertension and glaucomatous neurodegeneration.

Methods

Animals

Mice were maintained in a 12-hour light dark cycle and fed chow and water ad libitum. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology’s statement on the use of animals in research and approved by the University of Rochester’s University Committee on Animal Resources. A Bim null allele B6.129S1-Bcl2l11tm1.1Ast/J56 that had been backcrossed into C57BL/6J was obtained from Jackson Laboratory (B6.Bim). The B6.Bim colony was maintained by intercrossing. For glaucoma experiments, the null Bim allele was backcrossed into DBA/2J for 10 generations and then intercrossed (D2.Bim). Note, a null allele of Hrk57, another BH3-only protein that is known to facilitate, but not add to, BIM function58 was segregating in the D2 cross. Of the 22 D2.Bim-/- mice 41 eyes were assessed for optic nerve damage by PPD staining (described below; 3 either were not assessed or the histology was not of high enough quality to determine the level of glaucomatous damage). D2.Bim-/- eyes used in this study included the following Hrk genotypes: 3 Hrk-/-, 26 Hrk+/- and 12 Hrk+/+. Hrk deficiency did not appear to alter either the IOP profile or optic nerve damage in Bim-/- mice (not shown). In fact, one of the three double null mice had severe optic nerve degeneration and massive loss of RGC layer neurons. D2.Gpnmb mice were aged to 10 months and used as a control for DBA/2J mice. For the glaucoma experiments using the DBA/2J genetic background, male and female ratios were approximately equal between control and experimental eyes. The Jun and Six3 cre mice were crossed as previously described27.

Histology and cell counting

For immunohistochemistry and retinal flat mounting, eyes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at room temperature. The anterior segment was removed and eyes were processed for cryosectioning or whole mount staining as previously described1. POU4F1 (BRN3A, Santa-Cruz Biotechnology, 1:300) positive cells were counted in retinal cross sections in 40x fields located within 500 μm of the optic nerve head. In whole mounts, cleaved caspase-3 (activated caspase-3; R&D Systems, 1:1000) positive cells were counted in the retinal ganglion cell layer in eight 20x fields around the peripheral retina (specifically two fields from each quadrant approximately 220 μm from the peripheral edge). Also in the retinal ganglion cell layer, TUJ1 (Covance, 1:1000) positive cells were counted in eight 40x fields around the peripheral retina. For identifying RGCs in some experiments, B6.Cg-Tg(Thy1-CFP)23Jrs/J (Jax Stock Number 003710; referred to as B6.Thy1-CFP) mice were used (the allele was backcrossed into B6 >20 times). CFP was detected using a chicken anti-GFP antibody (Abcam, 1:500). BIM expression was detected using a rat anti-BIM antibody (A.G. Scientific, 1:300). BIM expression was checked in at least three areas of the retina from three retinas at each condition/time point examined. DBA/2J expression was examined in sections from six retinas. For RGC layer neuron counts, eyes were flat-mounted RGC layer up and stained with a modified Nissl stain as previously described3. All neurons in eight 40x fields (two fields per retinal quadrant) were counted for each eye. The fields were all equidistant from the retinal margin, centered approximately one 40X field from the margin. Nissl stains all retinal ganglion cell layer neurons and endothelial cells. Based on their obvious elongated, non-neuronal morphology, endothelial cells were excluded from the counts.

Mechanical injury of RGCs and Glaucoma

Controlled optic nerve crush (CONC) was performed as previously described1,3. Mice were anaesthetized with a mix of ketamine and xylazine. The optic nerve was crushed just behind the eye for approximately 4 seconds using self-closing forceps (Roboz RS-5027). Unmanipulated contralateral eyes or contralateral eyes that had a sham surgery performed (no crush of the optic nerve) were used as control eyes. All CONC experiments were performed on B6.Bim mice. DBA/2J mice were used as a glaucoma model. The null allele of Bim was backcrossed into DBA/2J mice for 10 generations and then intercrossed. The TonoLab (Colonial Medical Supply, Franconia, NH) was used to record IOP in D2.Bim mice. Mice were anaesthetized with a ketamine xylazine mix and IOP was recorded per manufacturers instructions between two and five minutes after administration of anesthetic. For determining the level of glaucomatous optic nerve damage, nerves were processed and stained with paraphenylenediamine (PPD) as previously described3,8,29 except that nerves were embedded in Technovit 7100 and 2 μm sections were cut and stained. Nerves were graded using a validated grading scale as previously described3,8,29. The grading scale places eyes into three categories: no or early, less than 5% of the axons are thought to be damaged or lost, a number that is consistent with age-related damage; moderate, many damaged axons throughout the nerve averaging about 30% of the axons judged to be damaged or lost, often there is localized signs of gliosis; severe, greater than 50% of the axons are judged to be damaged or lost and often signs of large areas of glial scarring. For plastic sections of retinas, eyes were processed and cut as previously described1.

Statistical Analysis

For RGC counts and cell death assessed by immunostaining, Bim+/+, Bim+/- and Bim-/- were considered independent groups and comparisons were made using ANOVA. Upon finding statistically significant differences between groups, the Tukey-Kramer method was used post-hoc to perform multiple comparison tests. P<0.05 was considered significant. These analyses included counts of cells labeled by Nissl stain, POU4F1, TUJ1, and CASP3 performed by an experimenter blind to genotype and/or experimental group. Standard error of the mean (SEM) is used to define the error bars for all cell counts. The Student’s t-test was performed to compare intraocular pressures grouped by age and genotype and counts of surviving GCL neurons grouped by optic nerve grade (n≥5) and genotype. D2.Bim-/- significantly diminishes optic nerve damage compared to Bim+/+ and Bim+/- littermates based on the chi-squared test.

Author Contributions

JMH conducted the majority of experiments and KAF contributed to the experiments detailed in Figure 5. RTL and JMH designed experiments and analyzed data. JMH wrote the manuscript with assistance from RTL. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Thurma McDaniel and Donna Shannon for technical help; the members of Kiernan, Freeman and Gan laboratories for helpful comments and discussion about the work; and Dr. Roth (Hrk), Drs. Wagner, Behrens and Stroller (Jun), and Dr. Furuta (Six3 Cre) for providing mice. This work was supported by EY018606 (RTL), T32 EY007125 (JMH), David Bryant Trust (RTL), The Glaucoma Foundation (RTL), Research to Prevent Blindness Career Development Award (RTL), and Research to Prevent Blindness unrestricted grant to the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Rochester.

References

- Harder J. M. & Libby R. T. BBC3 (PUMA) regulates developmental apoptosis but not axonal injury induced death in the retina. Mol. Neurodegener. 6, 50 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Schlamp C. L., Poulsen K. P. & Nickells R. W. Bax-dependent and independent pathways of retinal ganglion cell death induced by different damaging stimuli. Exp. Eye Res. 71, 209-213 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby R. T. et al. Susceptibility to neurodegeneration in a glaucoma is modified by Bax gene dosage. PLoS Genet. 1, 17-26 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosinger Ogilvie J., Deckwerth T. L., Knudson C. M. & Korsmeyer S. J. Suppression of developmental retinal cell death but not of photoreceptor degeneration in Bax-deficient mice. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 39, 1713-1720 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White F. A., Keller-Peck C. R., Knudson C. M., Korsmeyer S. J. & Snider W. D. Widespread elimination of naturally occurring neuronal death in Bax-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. 18, 1428-1439 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napankangas U., Lindqvist N., Lindholm D. & Hallbook F. Rat retinal ganglion cells upregulate the pro-apoptotic BH3-only protein Bim after optic nerve transection. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 120, 30-37 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semaan S. J., Li Y. & Nickells R. W. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the Bax gene promoter affects transcription and influences retinal ganglion cell death. ASN Neuro. 2, e00032 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell G. R. et al. Axons of retinal ganglion cells are insulted in the optic nerve early in DBA/2J glaucoma. J. Cell Biol. 179, 1523-1537 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D. R. & Hendrickson A. Effect of intraocular pressure on rapid axoplasmic transport in monkey optic nerve. Invest. Ophthalmol. 13, 771-783 (1974). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley H. A., Hohman R. M., Addicks E. M., Massof R. W. & Green W. R. Morphologic changes in the lamina cribrosa correlated with neural loss in open-angle glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 95, 673-691 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlamp C. L., Li Y., Dietz J. A., Janssen K. T. & Nickells R. W. Progressive ganglion cell loss and optic nerve degeneration in DBA/2J mice is variable and asymmetric. BMC Neurosci. 7, 66 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youle R. J. & Strasser A. The BCL-2 protein family: opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9, 47-59 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKernan D. P. & Cotter T. G. A Critical role for Bim in retinal ganglion cell death. J. Neurochem. 102, 922-930 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi T., Kosaka J. & Oshika T. JNK inhibitory kinase is up-regulated in retinal ganglion cells after axotomy and enhances BimEL expression level in neuronal cells. J. Neurochem. 95, 526-536 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan M., Doonan F. & Cotter T. G. Decreased expression of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members during retinal development and differential sensitivity to cell death. Dev. Biol. 291, 154-169 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doonan F., Donovan M., Gomez-Vicente V., Bouillet P. & Cotter T. G. Bim expression indicates the pathway to retinal cell death in development and degeneration. J. Neurosci. 27, 10887-10894 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Park S., Fei P. & Sorenson C. M. Bim is responsible for the inherent sensitivity of the developing retinal vasculature to hyperoxia. Dev. Biol. 349, 296-309 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J. A., Franklin T. B., Rafuse V. F. & Clarke D. B. The neural cell adhesion molecule is necessary for normal adult retinal ganglion cell number and survival. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 36, 280-292 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal-Nicolas F. M. et al. Brn3a as a marker of retinal ganglion cells: qualitative and quantitative time course studies in naive and optic nerve-injured retinas. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50, 3860-3868 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond I. D., Vila A., Huynh U. C. & Brecha N. C. Cyan fluorescent protein expression in ganglion and amacrine cells in a thy1-CFP transgenic mouse retina. Mol. Vis. 14, 1559-1574 (2008). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Archibald M. L., Stevens K., Baldridge W. H. & Chauhan B. C. Cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) expressing cells in the retina of Thy1-CFP transgenic mice before and after optic nerve injury. Neurosci. Lett. 468, 110-114 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohl S. G., Schmeer C. W., Witte O. W. & Isenmann S. Proliferative response of microglia and macrophages in the adult mouse eye after optic nerve lesion. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51, 2686-2696 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo-Romero C. et al. Axotomy-induced retinal ganglion cell death in adult mice: quantitative and topographic time course analyses. Exp. Eye Res. 92, 377-387 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putcha G. V. et al. Induction of BIM, a proapoptotic BH3-only BCL-2 family member, is critical for neuronal apoptosis. Neuron 29, 615-628 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness J. M. et al. Selective involvement of BH3-only Bcl-2 family members Bim and Bad in neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Brain Res. 1099, 150-159 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson G. A. & Madison R. D. Axotomized mouse retinal ganglion cells containing melanopsin show enhanced survival, but not enhanced axon regrowth into a peripheral nerve graft. Vision Res. 44, 2667-2674 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes K. A. et al. JNK2 and JNK3 are major regulators of axonal injury-induced retinal ganglion cell death. Neurobiol. Dis. 46, 393-401 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield J., Neame S. J., Paquet L., Bernard O. & Ham J. Dominant-negative c-Jun promotes neuronal survival by reducing BIM expression and inhibiting mitochondrial cytochrome c release. Neuron 29, 629-643 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby R. T. et al. Inherited glaucoma in DBA/2J mice: pertinent disease features for studying the neurodegeneration. Vis. Neurosci. 22, 637-648 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B. et al. Interacting loci cause severe iris atrophy and glaucoma in DBA/2J mice. Nat. Genet. 21, 405-409 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. G. et al. Genetic context determines susceptibility to intraocular pressure elevation in a mouse pigmentary glaucoma. BMC Biol. 4, 20 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon C. J., Strettoi E. & Masland R. H. The major cell populations of the mouse retina. J. Neurosci. 18, 8936-8946 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Semaan S. J., Schlamp C. L. & Nickells R. W. Dominant inheritance of retinal ganglion cell resistance to optic nerve crush in mice. BMC Neurosci. 8, 19 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley H. A. et al. Lack of neuroprotection against experimental glaucoma in c-Jun N-terminal kinase 3 knockout mice. Exp. Eye Res. 92, 299-305 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobs T. C., Libby R. T., Ben Y., John S. W. & Masland R. H. Retinal ganglion cell degeneration is topological but not cell type specific in DBA/2J mice. J. Cell Biol. 171, 313-325 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren D. et al. BID, BIM, and PUMA are essential for activation of the BAX- and BAK-dependent cell death program. Science 330, 1390-1393 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipuk J. E., Moldoveanu T., Llambi F., Parsons M. J. & Green D. R. The BCL-2 family reunion. Mol. Cell 37, 299-310 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel T., Plesnila N., Prehn J. H. & Henshall D. C. In vivo contributions of BH3-only proteins to neuronal death following seizures, ischemia, and traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 31, 1196-1210 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W. et al. Transcriptional up-regulation and activation of initiating caspases in experimental glaucoma. Am. J. Pathol. 167, 673-681 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. G. et al. Mutations in genes encoding melanosomal proteins cause pigmentary glaucoma in DBA/2J mice. Nat. Genet. 30, 81-85 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. G. in Ocular Disease: Mechanisms and Management (eds Levin L. A., & Albert D. M.) Ch. 21, 189-195 (Elsevier, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. G., Libby R. T., Gould D. B., Smith R. S. & John S. W. High-dose radiation with bone marrow transfer prevents neurodegeneration in an inherited glaucoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 4566-4571 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco A. et al. Reduced retina microglial activation and improved optic nerve integrity with minocycline treatment in the DBA/2J mouse model of glaucoma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 49, 1437-1446 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell G. R. et al. Absence of glaucoma in DBA/2J mice homozygous for wild-type versions of Gpnmb and Tyrp1. BMC Genet. 8, 45 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell G. R. et al. Molecular clustering identifies complement and endothelin induction as early events in a mouse model of glaucoma. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 1429-1444 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell G. R. et al. Radiation treatment inhibits monocyte entry into the optic nerve head and prevents neuronal damage in a mouse model of glaucoma. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 1246-1261 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby R. T. et al. Inducible nitric oxide synthase, Nos2, does not mediate optic neuropathy and retinopathy in the DBA/2J glaucoma model. BMC Neurosci. 8, 108 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado J., Murphy C. & Juster R. Trabecular meshwork cellularity in primary open-angle glaucoma and nonglaucomatous normals. Ophthalmol. 91, 564-579 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMenamin P. G., Lee W. R. & Aitken D. A. Age-related changes in the human outflow apparatus. Ophthalmol. 93, 194-209 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. & Vollrath D. Reversal of mutant myocilin non-secretion and cell killing: implications for glaucoma. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13, 1193-1204 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babizhayev M. A. & Yegorov Y. E. Senescent phenotype of trabecular meshwork cells displays biomarkers in primary open-angle glaucoma. Curr. Mol. Med. 11, 528-552 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zode G. S. et al. Reduction of ER stress via a chemical chaperone prevents disease phenotypes in a mouse model of primary open angle glaucoma. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 3542-3553 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieshaber M. C. & Flammer J. Blood flow in glaucoma. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 16, 79-83 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth J. et al. The path to open-angle glaucoma gene discovery: endophenotypic status of intraocular pressure, cup-to-disc ratio, and central corneal thickness. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51, 3509-3514 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan B. J., Wang D. Y., Pasquale L. R., Haines J. L. & Wiggs J. L. Genetic variants associated with optic nerve vertical cup-to-disc ratio are risk factors for primary open angle glaucoma in a US Caucasian population. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52, 1788-1792 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouillet P. et al. Proapoptotic Bcl-2 relative Bim required for certain apoptotic responses, leukocyte homeostasis, and to preclude autoimmunity. Science 286, 1735-1738 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaizumi K. et al. Critical role for DP5/Harakiri, a Bcl-2 homology domain 3-only Bcl-2 family member, in axotomy-induced neuronal cell death. J. Neurosci. 24, 3721-3725 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. P., Cape J. D., Klocke B. J. & Roth K. A. Deficiency of pro-apoptotic Hrk attenuates programmed cell death in the developing murine nervous system but does not affect Bcl-x deficiency-induced neuron apoptosis. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 59, 976-983 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]