Abstract

Background

Collaborative care interventions to treat depression have begun to be tested in settings outside of primary care. However, few studies have expanded the collaborative care model to other settings and targeted comorbid physical symptoms of depression.

Purpose

The aims of this report were to: (1) describe the design and methods of a trial testing the efficacy of a stepped collaborative care intervention designed to manage cancer-related symptoms and improve overall quality of life in patients diagnosed with hepatobiliary carcinoma; and (2) share the lessons learned during the design, implementation, and evaluation of the trial.

Methods

The trial was a phase III randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of a stepped collaborative care intervention to reduce depression, pain, and fatigue in patients diagnosed with advanced cancer. The intervention was compared to an enhanced usual care arm. The primary outcomes included the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale, Brief Pain Inventory, and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT)-Fatigue, and the FACT-Hepatobiliary. Sociodemographic and disease-specific characteristics were recorded from the medical record; Natural Killer cells and cytokines that are associated with these symptoms and with disease progression were assayed from serum.

Results and Discussion

The issues addressed include: (1) development of collaborative care in the context of oncology (e.g., timing of the intervention, tailoring of the intervention, ethical issues regarding randomization of patients, and changes in medical treatment over the course of the study); (2) use of a website by chronically ill populations (e.g., design and access to the website, development of the website and intervention, ethical issues associated with website development, website usage, and unanticipated costs associated with website development); (3) evaluation of the efficacy of intervention (e.g., patient preferences, proxy raters, changes in medical treatment, and inclusion of biomarkers as endpoints); and (4) analyses and interpretation of the intervention (e.g., confounding factors, dose and active ingredients, and risks and benefits of collaborative care interventions in chronically ill patients).

Limitations

The limitations to the study, although not fully realized at this time as the trial is ongoing, include: (1) heterogeneity of the diagnoses and treatments of participants; and (2) inclusion of caregivers as proxy raters but not as participants in the intervention.

Conclusions

Collaborative care interventions to manage multiple symptoms in a tertiary cancer center are feasible. However, researchers designing and implementing interventions that are web-based, target multiple symptoms, and for oncology patients may benefit from previous experiences.

Introduction

Background and rationale

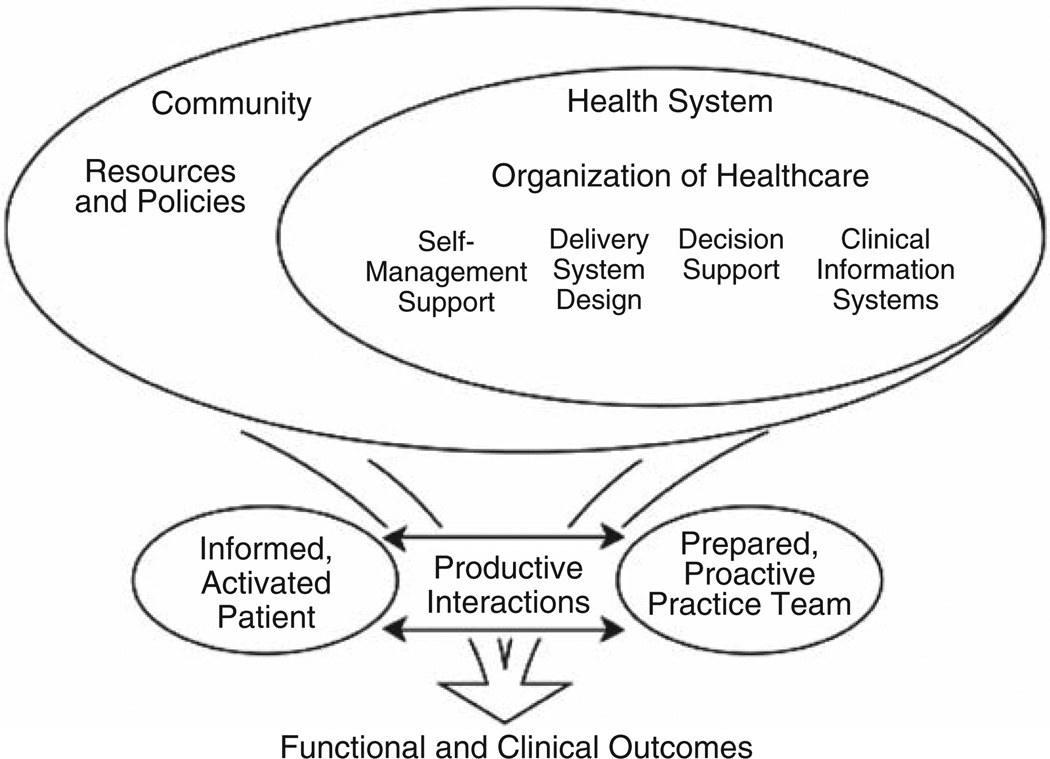

The collaborative care model is based on the principles of chronic disease management which includes the delivery of evidence-based treatments in partnership with the patient and a multidisciplinary team [1,2] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chronic disease management model

Collaborative care interventions have been designed and tested primarily to treat depression in the primary care setting [3]. The collaborative care intervention is intended to reflect patient preferences for treatment (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy and/or pharmacological intervention for depression) and the delivery of the intervention often includes an allied health care professional (HCP) who provides assessment, treatment, and monitoring of symptoms in collaboration with the patients’ physicians. The delivery of these interventions has varied but includes either face to face, telephone, and/or web-based modalities or a combination of these delivery modalities. In stepped approaches, the intensity or complexity of care is increased when necessary. The goal of the collaborative care approach is to ensure that all eligible patients have access to appropriate care, while reserving the most complex treatments for those who have demonstrated no benefit from less complex treatments.

Stepped collaborative care interventions for the treatment of depression have been demonstrated to be as effective as traditional face-to-face interventions in the general population and in people with chronic diseases [2–5]. A recent meta-analysis of 37 collaborative care intervention studies with 12,355 patients found that depression improved at 6 month follow-up and long-term benefits also were observed out to 5 years [3]. In this meta-analysis, collaborative care interventions that included a mental health professional as a care provider resulted in the largest effect sizes [3]. The number of sessions, type of therapeutic orientation, and timing of antidepressant initiation were not found to be significantly associated with the effectiveness of the intervention [3]. Collaborative care interventions have been effective at reducing health care utilization and costs [6–8]. Several studies have reported the mean incremental cost of treatment for depression to be lower with a collaborative care approach than with other treatment modalities [6–8].

The use of collaborative care interventions has begun to be expanded to other settings including oncology. Dwight-Johnson and colleagues reported significant reductions in depression in a sample of breast and cervical cancer patients using a collaborative care approach [7]. Similarly, Ell and colleagues found that a collaborative care intervention for the treatment of depression was effective in a sample of low income patients with mixed cancer diagnoses [8]. Finally similar to the current study, a collaborative care intervention targeting pain and depression was shown to reduce these symptoms in a mixed sample of cancer patients [9]. The aims of the present trial were to test the efficacy of a stepped collaborative care intervention to reduce pain, fatigue, and depression and improve overall quality of life in patients diagnosed with hepatobiliary carcinoma.

Cancer of the liver and bile ducts is a relatively rare disease in North America and Europe when compared to other cancer types. However, the incidence of liver and bile ducts cancer in the US continues to rise each year and the prevalence is expected to double in the next decade [10]. The latest reports estimate that there were approximately 27,000 new cases of liver and bile duct cancer in the US [11,12]. Liver cancer continues to account for substantial morbidity and mortality, is becoming increasingly important as a public health problem worldwide, and is a leading cause of cancer death in eastern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa and the sixth leading cause of cancer death worldwide [13].

People who present with liver cancer at an advanced stage in North America have a 3-year survival rate of less than 15% [14]. Nonsurgical treatment has been demonstrated to result, at best, in only modest improvements in survival [15–18]. As a result, improving or maintaining health-related quality of life (HRQL) is critical for the patient due to the poor prognosis. One way to improve HRQL is to assess and treat cancer-related symptoms that they experience during their treatment [13]. It has been estimated that 14–100% of people diagnosed with cancer report one or more cancer-related symptoms (e.g., depression, fatigue, and pain) depending on the type of cancer and treatment the individual receives. However, assessing and treating cancer-related symptoms in patients diagnosed with hepatobiliary carcinoma is challenging as many people are treated at tertiary care centers where patients visit infrequently and travel long distances for evaluation and treatment. With the use of multiple delivery strategies (e.g., telephone, face to face, and website), it is expected that a larger number of patients who may have financial constraints, transportation problems, symptom burden, or limitations of time due to work or caregiving responsibilities would be able to access treatment using a collaborative care approach.

The challenges associated with the evaluation of the efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions has become increasingly recognized. New guidelines were recently published to address issues related to the complex design and evaluation of non-pharmacological trials [19]. Issues that are specific to non-pharmacological trials include difficulties with double blind designs, measurement of the ‘active’ ingredients or ‘dose’ of treatments, intervention fidelity, reproducibility, and generalizability of the treatments [19]. The extension of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for non-pharmacological trials was a critical step in increasing the consistency of reporting clinical trials and the design and implementation of high quality trials of nonpharmacological interventions.

The aims of this report are to: (1) describe the design and methods of a trial testing the efficacy of a stepped collaborative care intervention designed to manage depression, pain, and fatigue and improve overall quality of life in patients diagnosed with hepatobiliary carcinoma; and (2) share the lessons learned during the design, implementation, and evaluation of the trial and address issues that are unique to non-pharmacological trials.

Design and methods

The randomized controlled trial (RCT) included two arms, the collaborative care intervention arm and an enhanced usual care arm. The primary outcomes used to evaluate the efficacy included the assessment of changes in pain, fatigue, depression, HRQoL, and biomarkers shown to be associated with the target symptoms, side effects, and disease progression in liver cancer. The team of investigators who designed and conducted this trial included experts in the areas of surgical oncology, epidemiology, caregiving, biostatistics, clinical health psychology, and immunology.

Pilot and feasibility testing of the intervention

Prior to the commencement of the RCT, two pilot studies were conducted to assess the (1) feasibility of the collaborative care intervention and to estimate effect sizes in order to project the sample size needed for the phase III trial; and (2) assess acceptability, usage, and satisfaction of the website designed for use in the RCT. In the first pilot study of 28 patients, quantitative interviews were performed to assess changes in primary outcomes at baseline and 3 and 6-months follow-up. Details regarding this pilot study have been published elsewhere [20]. In the absence of published effect sizes for a collaborative care intervention including the proposed target symptoms, we used effect sizes from the pilot study to guide the estimate for the sample size for the RCT. Based on the effect sizes for the pilot study, it was estimated that a sample of 256 participants would yield a power of 0.90 or greater for the primary outcomes, possibly with the exception of fatigue [21]. The second pilot study of 13 patients focused on evaluation of the preliminary version of the website to assess satisfaction with the content as well as technical or user problems. Based on qualitative interviews, the design and content of the website were refined prior to the commencement of the phase III RCT.

Phase III RCT

Design

The phase III RCT was designed to test the efficacy of a stepped collaborative care intervention in advanced liver cancer patients with respect to reducing symptoms of pain, depression, and fatigue and improving overall quality of life. The trial commenced in January 2007. The participants were followed from the time of enrollment for 2 years or until death.

Study arms

Patients were randomized to one of two arms, the stepped collaborative care intervention arm or enhanced usual care arm. The stepped collaborative care intervention is based on the patient’s presenting problem (e.g., pain and depression) and preference for treatment (e.g., cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological); however a combination of both cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological treatment was recommended for treatment of targeted symptoms. Each of the treatment approaches was empirically based [22–25] and followed a detailed protocol. Therapists were doctoral level psychologists with experience in psycho-oncology who received weekly supervision from the principal investigator. Treatment fidelity encompasses strategies to monitor and enhance the reliability and validity of the study design as well as to the implementation of the intervention [26]. In this study, treatment fidelity was maintained through (1) the use of Study 360 clinical trials software to monitor timing of evaluation and collection of blood, (2) the use of a Microsoft ACCESS database to assess the dose and active ingredients of the collaborative care intervention, (3) hiring care coordinators with education and experience in psycho-oncology, (4) weekly supervision of the care coordinators and project director by the principal investigator, and (5) observation of face to face and telephone follow-up contacts by the care coordinator and retraining when necessary.

Study 360 is a multi-component, web accessible software system designed to reduce management burden, increase efficiency and improve visibility of clinical trials. The system provides a set of tools designed for daily use by clinical and project management staff. A tracking tool records the dates of various protocol events for each research subject. A reminder system scans the tracking data to provide automated study activity management. Progress reports provide instant, real-time access to the current state of the study. A shared appointment calendar integrates with the reminder system to temporarily suppress reminders for scheduled tasks. An adaptive randomization tool maintains a balance of various blocking factors across treatment groups. The Study 360 database is centralized with secure user access provided via a web browser and is thus well suited for both single and multi-site studies.

The delivery of the intervention included face to face visits whenever the patient came into the outpatient clinic or hospital for cancer treatment, telephone follow-up with a minimum of two telephone contacts (before and after the patients’ cancer treatment) between cancer treatments, and access to a website that was designed specifically for this RCT, which includes educational information, a self-management area, journaling, a chat room, an audiovisual library, peer support, and other resources. The website also includes a text to voice option to address issues of literacy and a larger font for older adults. Patients had more frequent contact with the care coordinator (stepped) if their symptoms did not decrease with initial intervention.

The ‘enhanced usual care’ arm of the RCT included routine medical care from the nurse coordinator and attending physician. Patients in both arms received interviews to assess symptoms at baseline (prior to their first cancer treatment) and every 2 months for the first year and then every 6 months for year 2 or until the death of the patient. Enhanced referred to a brief intervention for any participant who reported depressive symptoms in the clinical range, significant distress, or severe pain. For these patients, the care coordinator was contacted by the interviewer immediately and the patient or caregiver was contacted by telephone to provide feedback of their results, assesses the severity of symptoms, and provide treatment options for the patient and/or caregiver in their local area. Patients in both arms received a binder with educational information, contact information for the nurses and support staff within the Liver Cancer Center, and access to a 24-h, 7-day a week toll-free number that can be used to contact one of the Liver Cancer Center’s clinical nurse coordinators when needed.

Participants and eligibility criteria

Patient inclusion criteria were: (1) biopsy, radiological, and/or biological evidence of hepatobiliary carcinoma; (2) age 18 years or older; and (3) fluency in English. Exclusion criteria included: (1) current suicidal or homicidal ideation, or (2) current psychosis, or thought disorder. Caregivers are identified by the patient as a family member or friend who assists them in the care of their cancer and treatment. Caregivers also provide consent to participate in the study. Exclusion criterion for caregivers included psychosis, thought disorder, current suicidal ideation. If a caregiver reported these symptoms, s/he was referred for inpatient or outpatient psychiatric treatment or psychotherapy.

Randomization sequence generation

Patients are assigned randomly to the collaborative care intervention arm or enhanced usual care arm. A minimization process was employed to achieve balance between gender and vascular invasion. Liver cancer has a 2 : 1 male to female ratio, and better prognosis often has been observed in female patients [27]. One of the most robust and consistent predictors of survival in liver cancer is vascular invasion [28]. Patients were stratified on these two factors.

Allocation concealment

Allocation concealment was achieved through a procedure developed by the study statistician using a random number table that assigned consecutive patients across group. A research assistant who was not part of the study placed the trial assignments in opaque envelopes consecutively by group. These opaque envelopes were sealed, numbered serially, and placed into four numbered containers, one for each stratification subgroup. The statistician put the randomization table in a sealed envelope to be opened only at the end of the trial.

Blinding

Consistent with most non-pharmacological trials, patients and therapists could not be blinded to group assignment; however telephone interviewers who were involved in collecting data regarding the efficacy of the intervention were blinded to which arm of the study the patient and caregiver were assigned.

Recruitment and compensation

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to the commencement of the study. The recruitment of patients and caregivers takes place in a large tertiary cancer center that evaluates and treats patients with hepatobiliary carcinoma. Four attending oncologists (TCG, JWM, DAG, and AT) refer patients to the study who meet the inclusion criteria. Patients who were interested in speaking to a therapist about participation are provided with information regarding the risks and benefits of the study and details regarding compensation ($10 per interview and $10 per blood draw), and the frequency of the intervention and telephone interviews. Patients (and caregivers) who consent to participate were scheduled for a telephone interview before their first cancer treatment. Intake interviews were performed with patients who were assigned to the collaborative care intervention arm.

Evaluation of intervention

To evaluate the efficacy of the intervention, interviews were conducted prior to the patients’ first cancer treatment (usually within 1–14 days after being consented) and every 2 months for 1 year. After 1 year, patients and caregivers were interviewed every 6 months for 2 years or until death. To evaluate the efficacy of the collaborative care intervention, trained telephone interviewers follow a structured clinical interview that was included on the website. Interviews were completed with patients and caregivers, and the duration of the interviews was approximately 60 min. Caregivers were included as proxies for the patients as it was expected that as the patient’s disease progresses that they may be unable to complete interviews. Prior research, by this team and others, has demonstrated that family caregivers have a high level of agreement with patients when rating their loved one’s symptoms and provide a relatively accurate report of patient symptoms and HRQoL [29–32]. The primary and secondary endpoints as well as mediators and moderators can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Outcomes, mediators, and moderators testing the efficacy of the collaborative care intervention

| Construct | Instrument | Patient report |

Caregiver report |

Caregiver report of patient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcomes | ||||

| Depression | Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale [39] | X | X | X |

| Pain | Brief Pain Inventory [40] | X | X | X |

| Fatigue | Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Anemia Scale [41] | X | X | X |

| Quality of Life | Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Hepatobiliary Questionnaire [42] | X | X | X |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Anxiety | State Trait Anxiety Inventory-Short Form [43] | X | X | |

| Sleep quality | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [44] | X | X | |

| Sexual functioning | Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire [45] | X | X | |

| Substance use | Type, amount, frequency, duration of alcohol, drugs, and tobacco | X | X | |

| Healthcare utilization | Assessment of visits to other mental health professionals, physicians, emergency room, specialists, etc. | X | X | |

| Satisfaction with healthcare | FamCare [46] | X | X | |

| Moderators/mediators | ||||

| Patient-caregiver relationship | Primary Relationship Questionnaire | X | X | |

| Spiritual well-being | Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Spiritual Well-Being Scale [47] | X | X | |

| Illness perception | Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire [48] | X | X | |

| Emotional expression | Courtland Emotional Control Scale [49] | X | X | |

| Optimism | Life Orientation Test [50] | X | X | |

| Caregiver stress | Caregiver Quality of Life Index-Cancer scale [51] | X | ||

| Anticipatory grief | Anticipatory Grief Scale [52] | X | ||

| Traumatic events | Traumatic Events Questionnaire [53] | X | X | |

| Posttraumatic growth | Posttraumatic Growth Inventory [54] | X | X | X |

Lessons learned

The lessons learned to date from the design, implementation, and evaluation of this trial are several fold. Although collaborative care interventions have now been tested for over a decade, this type of intervention only recently has begun to be tested in the context of cancer and with symptoms other than or in addition to depression. Furthermore, the reporting standards for clinical trials with non-pharmacological interventions continue to be refined. Recommendations derived from our experience may facilitate the design and implementation of clinical trials of collaborative care interventions that may extend beyond the primary care setting and treatment of depression.

Collaborative care interventions in the context of cancer

The use of collaborative care has begun to be employed in the context of cancer but at this time is relatively limited [7–9]. With continued experience testing these types of interventions, and the publication of CONSORT guidelines for non-pharmacological trials; it is expected that the rigor of the design, implementation, evaluation, and reporting of non-pharmacological trials will continue to improve. Testing the efficacy of collaborative care and other psychosocial interventions remains challenging as the interventions are often complex and investigators are unable to employ blinding at all levels of implementation (e.g., therapists and patients cannot be blinded). Issues that arose regarding the design and implementation of the intervention in our RCT included: (1) the timing of the intervention in a population of patients who travel long distances to receive cancer treatment and who may be very ill; (2) tailoring the intervention to address individuals presenting problems; (3) ethical issues regarding randomization of patients; and (4) changes in the medical treatment of patients and necessary modifications to the collaborative care intervention and/or evaluation of the intervention needed to reflect these changes.

The collaborative care model provides a framework for addressing some of the additional needs of patients diagnosed with advanced cancer. The intervention was designed so that the patients would not be required to make additional visits to the medical center as many patients were coming from far away to complete their cancer treatment. During the pilot testing of the intervention, patients reported not being able to attend additional appointments due to (1) distance to the hospital, (2) cost of transportation, (3) limited time due to work or caregiving responsibilities, or (4) symptoms of cancer or side effects of treatment. During the pilot phase of the study, a subset of patients also reported that they tried to ‘forget’ about the cancer and wished to maintain ‘normal life’. Thus, some patients preferred not to be reminded of their cancer between visits to the medical center. These patients were contacted by the care coordinator only at specific times (e.g., before and after cancer treatments) and follow-up contact was made only when needed to manage symptoms. Other patients preferred more frequent contact and/or face to face visits to manage symptoms or treatment side effects. The strategy of varying the frequency, duration, and content of the intervention is reflective of the ‘stepped’ approach described earlier. The frequency, content, method, and duration of contact were recorded for analyses.

The current trial was an adaptive treatment strategies (or dynamic treatment regime) which included a set of decision rules that specified when to change the intensity or type of treatment. The decision rules employ variables such as patient response to treatment, risk, burden, adherence to treatment, and preferences for assessment and treatment collected during prior sessions. The outcomes used to assess the efficacy of the intervention reflected the individuals’ presenting problems and preferences for treatment. As a result, rather than applying the same intervention for all patients, the intervention matched the patients’ presenting problems with the overall goal of maximizing the patients’ quality of life.

Patients diagnosed with hepatocelullar carcinoma who were referred for transplantation and had active substance abuse or dependence were recommended to have at least 6 months of abstinence from drugs and alcohol at our transplant center prior to listing. With a diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma patients may only have a short period of time in which they may be eligible for this life saving treatment. Therefore, evidence-based treatments for substance dependence were recommended and the collaborative care intervention was employed to monitor patients’ maintenance in treatment as well as to assess and treat cancer-related symptoms. Outcome data for patients who are referred for transplantation will be analyzed using intent to treat as well as the actual randomization of patients to the study arm.

Novel cancer treatments were also introduced over the course of this psychosocial intervention trial (e.g., sorafenib). As a result of these new cancer treatments, modifications to the website and collaborative care intervention as well as the outcomes were required. Issues related to budget and appropriate staff to respond to such changes should be considered in future trials.

Web-based interventions

Web-based interventions have been developed to reduce health care costs and to extend interventions to patients who otherwise may not have access to traditional face-to-face interventions. However, concerns regarding disparities (e.g., age, socioeconomic status) in accessing technology such as websites continue to be debated. Many issues related to the development of the website and implementation of the intervention arose over the course of the study including: (1) access to the website by the target population; (2) involvement of the medical staff in the design of the website; (3) ethical issues surrounding the design of the website; (4) ease of use of the different components of the website; and (5) costs associated with website development and maintenance and web-based intervention implementation. The participants utilized the website as much or little as they preferred. The investigators tracked the usage (page content, frequency, and duration) over the course of the study to determine how much the website contributed to the effectiveness of the intervention (Table 2).

Table 2.

Website visits and duration on each section of website (n = 226 total participants and 108 intervention patients)

| Section of website | Page views |

Total duration (in min) |

Section of website | Page views |

Total duration (in min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home page | 135 | 136.8 | My journal | 49 | 88.7 |

| The Liver Cancer Center | End of life | ||||

| Intro page | 36 | 61.7 | Intro page | 18 | 17.1 |

| Your first visit | 0 | 0 | Palliative care | 3 | 3.4 |

| Meet the staff | 15 | 22.9 | End of life | 3 | 5.6 |

| Arriving in Pittsburgh | 2 | 8 | Advance directives | 1 | 2.2 |

| Directions to the center | 1 | 1.7 | CPR and DNR | 0 | 0 |

| Lodging | 6 | 39.4 | Final days | 0 | 0 |

| Managing your cancer care | 23 | 44.8 | Hospice care | 0 | 0 |

| Medical dictionaries | 4 | 14.5 | Bereavement | 4 | 5.1 |

| Total | 87 | 193 | Total | 29 | 33.4 |

| Managing symptoms | Diagnosis & Tx of liver cancer | ||||

| Intro page | 31 | 19.9 | Intro page | 37 | 10.6 |

| Fatigue | 11 | 17.3 | Your liver | 11 | 47.9 |

| Pain | 6 | 2.8 | Anatomy/functions | 9 | 19.5 |

| Depression | 4 | 25.0 | Symptoms | 13 | 22.6 |

| Anxiety | 9 | 16.3 | Diagnosis | 6 | 21.7 |

| Sleep | 4 | 15.6 | Types | 20 | 63.3 |

| Sexual dysfunction | 1 | 0.5 | Treatments at UPMC | 27 | 41.5 |

| Other side effects | 43 | 65.7 | Research at UPMC | 11 | 21.6 |

| Total | 109 | 163.1 | Total | 134 | 248.7 |

| Staying healthy | What others say | ||||

| Intro page | 23 | 5.8 | Intro page | 64 | 33.8 |

| Smoking cessation | 6 | 17.9 | Stories of hope | 19 | 48.7 |

| Drugs and alcohol | 3 | 3.2 | Chat room | 37 | 26.2 |

| Physical fitness | 7 | 9.1 | Bulletin board | 39 | 32.5 |

| Nutrition | 34 | 43.2 | Expert chat | 111 | 49.8 |

| Stress | 9 | 10.1 | Total | 192 | 161.9 |

| Total | 82 | 89.3 | |||

| How am I doing? | Family caregivers | ||||

| Intro page | 29 | 12.1 | Intro page | 26 | 18.7 |

| Quality of life | 6 | 3.5 | Who is a caregiver | 3 | 2.9 |

| Pain | 5 | 10.6 | Caregiving | 9 | 22.6 |

| Fatigue | 11 | 22.5 | Mind, body, & spirit | 3 | 7.7 |

| Depression | 8 | 19 | Talking with health care professional | 2 | 4.5 |

| Anxiety | 5 | 7.8 | Talking with family | 1 | 5.5 |

| Posttraumatic growth (patient) | 3 | 4.2 | Life planning | 2 | 0.8 |

| Posttraumatic growth (caregivers) | 6 | 11.1 | Advanced cancer | 1 | 4.1 |

| Sexual history | 1 | 0.2 | Reflection | 0 | 0 |

| Past trauma: childhood | 1 | 0.2 | Bill of rights | 2 | 1.2 |

| Past trauma: recent | 1 | 0.2 | Personal affairs | 3 | 2.2 |

| Caregiver stress | 4 | 9.5 | Death is near | 4 | 5.9 |

| Illness perception | 1 | 0.2 | Resources | 2 | 15.1 |

| Total | 81 | 101.1 | Helpful articles | 3 | 8.9 |

| Total | 61 | 100.1 | |||

| Resources | Audio/video library | ||||

| Intro page | 18 | 10.5 | Intro page | 27 | 31.5 |

| Cancer | 3 | 0.5 | Meet the staff | 23 | 21.4 |

| Liver | 3 | 3.1 | Stress coping | 10 | 13.6 |

| Patient education materials | 3 | 3.2 | Educational videos | 17 | 8.2 |

| End of life | 2 | 3.6 | Total | 77 | 74.7 |

| Legal information | 0 | 0 | |||

| Cancer advocacy | 2 | 18.1 | |||

| Caregiver support | 1 | 2.0 | Help | 5 | 3.0 |

| Children and adolescents including grandchildren | 0 | 0 | |||

| Medical directories | 1 | 0.2 | Search | 26 | 40.2 |

| Health insurance | 4 | 2.5 | |||

| Airline transportation | 0 | 0 | Totals | 1384 | 1687.4 |

| Drug information | 5 | 14.3 | |||

| Clinical trials | 3 | 1.2 | |||

| Complementary/alternative Tx | 2 | 3.2 | |||

| Pharmaceutical companies | 0 | 0 | |||

| Total | 47 | 62.4 |

CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; DNR, do not resuscitate.

Prior to the commencement of the trial, a survey (n = 100) was conducted to assess the percentage of patients evaluated at the Liver Cancer Center who did not have access to the internet or a computer. The results of the survey suggested that up to 40% of patients may not have access to a computer or internet service. However, with 220 patients enrolled in the RCT as of 12/15/2010 we have lent computers to only 6 patients (4%). Two additional patients did not have access to computers but preferred printed materials or access to the website from the local library (1%). Although we had budgeted for technical support in case patients needed assistance beyond that provided by the care coordinator, to date no patient has requested technical support despite the relatively high usage of the website statistics.

Future analyses will address (1) patients’ satisfaction with the content of the website, (2) frequency and duration of website use, and (3) contribution of the website use to efficacy of the intervention (e.g., reductions in depression, pain, fatigue, and improvement in quality of life). Analyses by method of delivery of the intervention, presenting problems, content of the contact (e.g., education, cognitive-behavioral strategies, and pharmacological intervention) will be performed to understand the ‘dose’ and active ingredients of this collaborative care intervention.

For web-based interventions, or for those interventions which include a component that uses a website, attention to the specific population to which the intervention is targeted is critical for the team designing the website. The development and pilot test of the study website took approximately 9 months and over 500 pages of content that required compilation, editing, and testing to make certain it was written at a 6th to 8th grade reading level and was acceptable to patients. A large font was used to accommodate the changing vision of older adults. Because we included a text-to-voice option, participants also had the option to listen to the content of the website.

Center staff assisted in the development of the content to increase the utility and credibility of the educational videos regarding the etiology, assessment, and treatment of different cancer-related symptoms that were included on the website. The staff also developed a binder of printed educational information for all patients. It is not known whether the availability of both videos and printed information to staff will affect our ability to detect differences between groups when assessing the efficacy of the intervention. Clinicians involved in the care of the patient population should be consulted when developing the collaborative care intervention but not necessarily be privy to the content of the intervention if they are part of the ‘usual care’ arm.

Inclusion of patient stories and pictures on the website required additional approval from the Institutional Review Board and consents from the patients and caregivers. Some patients also appreciated the opportunity to speak to other patients who have been diagnosed and received treatment at the same center. With the patient’s permission, we were able to connect interested patients. Although the health care providers’ opinion is highly regarded by patients when making decisions between treatments, or in the case of advanced cancer whether to be treated or not, patients reported that information from other patients was often invaluable.

Despite not teaching patients how to use the website or sending reminders to use the website over the course of the study, patients accessed the website frequently, primarily near the time of diagnosis or when the disease began to progress. Designers of future studies that provide a website component may wish to allow for time for the care coordinators to demonstrate to patients how to access and use the website and also to provide reminders to patients in the collaborative care arm to utilize the website. Many medical centers have regulations regarding email contact between patients and health care providers, therefore making it difficult to use email as a possible form of communication between patients and health care providers. However, recent advances in Electronic Medical Records systems which include email exchanges between patients and health care providers is becoming increasingly common.

Synchronous website components (e.g., chat room) were not utilized by participants as frequently as expected due to the large number of participants needed to be enrolled at any one time. Although attempts were made by the study staff to schedule times for trial participants to chat with one another or with members of the health care team, participants did not take advantage of these opportunities. The bulletin board option (asynchronous) was utilized much more frequently as a way to communicate among participants. To date, in this study, the three most frequently utilized sections of the website were: (1) what others say (e.g., videos by staff, stories by other participants), (2) information on the diagnosis and treatment of liver cancer, and (3) information on managing symptoms and side effects.

Finally, the costs associated with web-based interventions vary greatly depending on the content and sophistication of the website. In addition to development and maintenance costs, investigators in future studies that include a website as part of an intervention should consider the cost of server space for the duration of the study, and beyond if data are included, as well as the annual cost of security (SSL) certificates.

Evaluation of the collaborative care intervention

The evaluation of collaborative care interventions can be challenging. Unlike pharmacological trials in which outcomes typically are based on clinical laboratory tests and measurements, psychosocial interventions may include a broad range of outcomes. Interventions that are individually tailored increase the complexity of evaluation. The use of Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial (SMART) is becoming increasingly recommended for time varying adaptive interventions [33]. Several issues have arisen over the course of the study to date: (1) patient preferences in regard to the method of assessment; (2) caregivers as proxy raters; (3) changes in medical treatment; and (4) biological outcomes after psychosocial interventions.

Although telephone interviews were planned to assess the efficacy of the intervention, we learned that flexibility in regard to the patients’ and caregivers’ preferences for data collection was important for retention of participations and to reduce missing data. Due to participants’ problems with scheduling, time constraints, hearing problems, or participant preferences, we provided the option of using paper and pencil questionnaires as an alternative to telephone interviews. We also had a few patients request to complete the questionnaires online. Also, an increasing number of people have only cell phones and no land line with financial constraints on cell phone usage.

Caregivers were included as proxy raters of patient symptoms and HRQL in this study as the majority of patients in this trial had been diagnosed with advanced cancer. As the disease progressed, it was expected that patients would not be able to complete interviews or questionnaires. Agreement, as analyzed using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), between the patient and caregiver ratings of cancer-related symptoms and side effects and quality of life has been adequate (ICC for pain = 0.63, p = 0.001; ICC for fatigue = 0.63, p = 0.001; ICC for depression = 0.21, p = 0.05; and ICC for quality of life = 0.67, p = 0.001). However, we found that caregivers also had difficulties completing interviews as the patient’s disease progressed because they often were overwhelmed with caregiving responsibilities, particularly at the end of life. A recent study concluded that caregivers provide support for their loved one for approximately 66 h a week in the last year of their loved one’s life [34].

Although the primary reason for including the caregivers in this study was to assess the patients’ symptoms, it was recognized that caregiver distress was a significant issue. Additional instruments were added to assess the caregivers’ stress and depressive symptoms. Preliminary analyses show that 38% of caregivers have reported depressive symptoms in the clinical range (as measured by the CES-D) prior to the initiation of cancer treatment of their loved ones. Caregiver stress was found to be similar to those family members who had loved ones in hospice care [35].

Future studies that involve caregivers of patients with terminal illnesses should have appropriate administrative and clinical staff for the management of distress and depression in caregivers, particularly when caregivers serve as proxy raters. Ongoing assessment and intervention for the family caregiver may be needed after the death of the loved one [36]. Ideally, this support would be provided by the same study team, given that research has demonstrated that caregivers do not take advantage of bereavement services offered by hospice [37,38] possibly due to the typically short time during which families work with hospice teams.

Some patients, while enrolled in our trial, received treatment in their community. Assessment of symptoms and HRQL continued primarily through telephone interviews. To collect data on biomarkers, tubes for blood collection were sent to patients’ homes for them to have blood drawn at a local laboratory at the time of their routine blood work. We found this method very effective in collecting samples when the patient did not return to our center.

Many studies that include biological outcomes do not take into consideration the importance of the timing of the collection of blood. One aim of this study was to determine the association between symptoms and side effects and immunological parameters. Therefore, the blood draws are performed prior to cancer treatment, before the administration of dexamethasone and other medications (e.g., Ativan), and before chemotherapy was administered. Psychosocial assessments and blood samples also are collected approximately 2 months after regional chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery to avoid influence associated with the treatment or acute side effects of treatment, such as pain or fatigue. Blood samples are collected between 8 am and noon whenever possible. Statistical methods will be used to address issues with patients whose blood was not taken during this time period.

Analyses and interpretation of collaborative care interventions

Although the between groups analyses have not yet been performed, several issues have arisen thus far that will be considered in regard to the analyses and interpretation of the results including: (1) possible confounding factors secondary to heterogeneity of the sample, (2) measurement of the dose or active ingredients of the intervention, and (3) symptoms or side effects (e.g., encephalopathy, severe vomiting and dehydration) requiring attention from the medical team, and (4) potential differences between therapists.

Conclusions

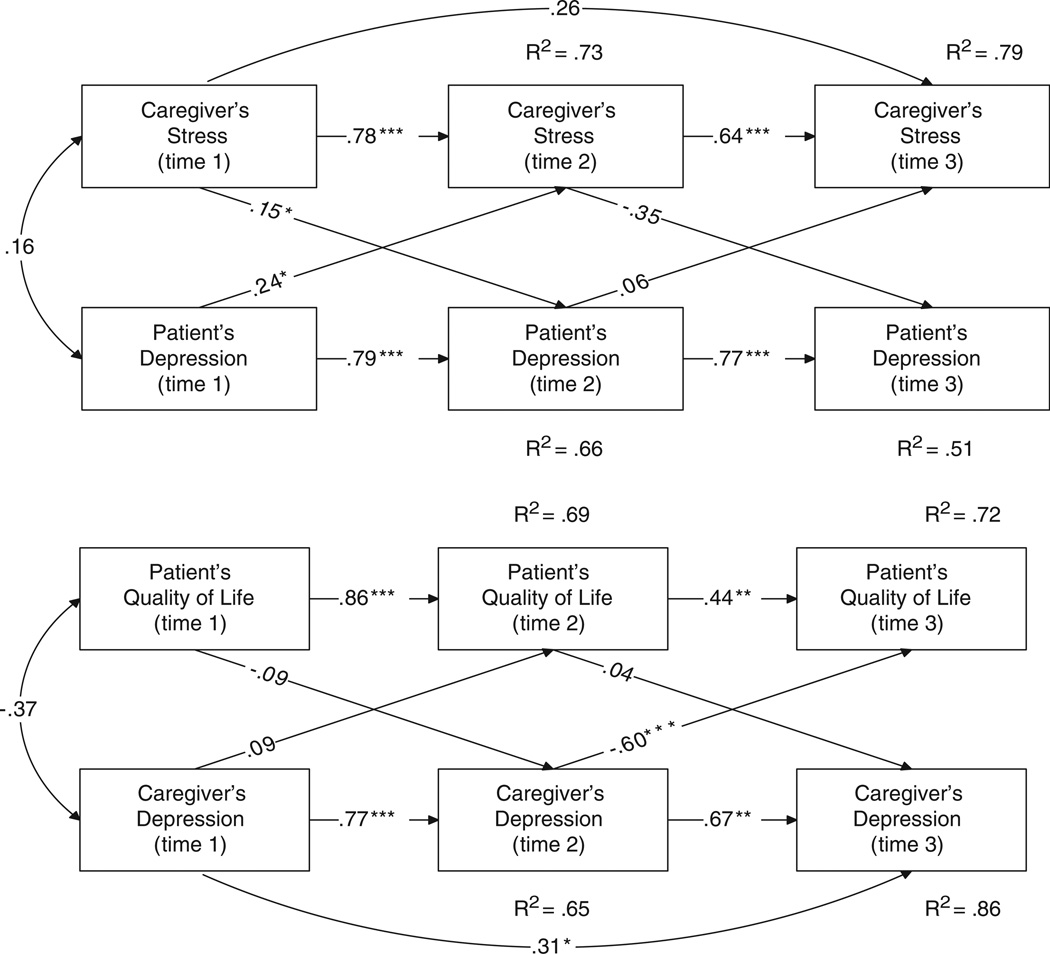

The lessons learned and recommendations from this trial thus far fall into four broad areas: (1) issues related to the development of collaborative care intervention in the context of cancer; (2) issues related to web-based interventions with medical populations; (3) challenges in evaluation of the efficacy of collaborative care; and (4) analyses and interpretation of the efficacy of the intervention. The limitations to the study, although not fully realized as the trial is ongoing include: (1) heterogeneity of the diagnoses and cancer treatments included in the study; and (2) caregivers as proxy raters rather than intervention participants. The last point has begun to be addressed as our team has found that patient-caregiver interdependence in regard to psychological functioning. Therefore, treatment of the patient and caregiver as a dyad is recommended (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The effects of the patient and caregivers’ psychological functioning on their partner. Note: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the patients and caregivers who gave their precious time to participate in this study. We are also very grateful to Jackie Barnes, Gretchen Foster, Cindy Wiltsie, Ann Pitcairn, Elaine, Roberta Gillespie, Nicole Bonnaci, Valerie Switzer, Elaine Farmer, Laura Stergis, Pat Boden, Judy Dick, Koty Nadeau, Justin Lazaroff, Andrea Dunlavy, and Debra Brower. The study would not be possible without their dedication to patient care and research.

Funding

Grant support: NCI5K07CA118576-02 K07CA11 8576-04S1; 1R21CA127046-01A1; University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Liver Cancer Center.

References

- 1.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, et al. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2314–2321. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, et al. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:1097–1102. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-12-199712150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Stepped collaborative care for primary care patients with persistent symptoms of depression: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:1109–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon GE, Katon W, VonKorff M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a collaborative care program for primary care patients with persistent depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1638–1644. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu CF, Hedrick S, Chaney EF, et al. Cost-effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in a primary care veteran population. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:698–704. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.5.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dwight-Johnson M, Ell K, Lee PJ. Can collaborative care address the needs of low-income Latinas with comorbid depression and cancer? Results from a randomized pilot study. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:224–234. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.3.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ell K, Xie B, Quon B, et al. Randomized controlled trial of collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4488–4496. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroenke K, Theobald D, Wu J, et al. Effect of telecare management on pain and depression in patients with cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304:163–171. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altekruse S, McGlynn KA, Reichman ME. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, mortality, and survival trends in the United States from 1975 to 2005. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1485–1491. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.orner MJ, Ries LAG, Krapcho M, et al., editors. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2006. National Cancer Institute; [accessed 3 September 2009]. Table I-21, US Prevalence Counts, Invasive Cancers Only, January 21, 2006, Using Different Tumor Inclusion Criteria. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/results_single/sect_01_table.21_2pgs.pdf on September 3, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Prevalence database: ‘US Estimated 31-Year L-D Prevalence Counts on 1/1/2006’. National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Statistical Research and Applications Branch, released April 2009, based on the November 2008 SEER data submission. www.seer.cancer.gov.

- 13.Harrison TJ. Viral Hepatitis and primary liver cancer. In: Arrand JR, Harper DR, editors. Viruses and Human Cancer. Oxford: BIOS Scientific Publishers Limited; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.NIH. State-of-the-Science Statement on symptom management in cancer: pain, depression, and fatigue. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2002;19:1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Camma C, Schepis F, Orlando A, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Radiology. 2000;200:47–54. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2241011262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geschwind JF, Ramsey D, Choti M, et al. Chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma: results of a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2003;26:344–349. doi: 10.1097/01.COC.0000020588.20717.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trial for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003;37:429–442. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tinchet JC, Ganne-Carrie N, Beaurant M. Review article: intra-arterial treatments in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;17:111–118. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.17.s2.19.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, et al. CONSORT Group. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann of Intern Med. 2008;148:295–309. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-4-200802190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steel J, Nadeau K, Olek M, Carr BI. An individually tailored psychosocial intervention for patients with advanced hepatobiliary carcinoma: a pilot study. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2007;25:19–42. doi: 10.1300/J077v25n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kraemer H, Mintz J, Noda A, et al. Caution regarding the use of pilot studies to guide power calculations for study proposals. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:484–489. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beck AT, Rush A, Shaw B, Emery G. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewinsohn PM, Munoz R, Youngren M, Zeizz AM. Control Your Depression. New York: Fireside; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bandora A, editor. Social Learning Theory. Oxford: Prentice-Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ory M, Jordan T, Bizarre T. The behavior change consortium: setting the stage for a new century of health behavior-change research. Health Education. 2002;17:500–511. doi: 10.1093/her/17.5.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellg A, Borrelli B, Resnick B, et al. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the behavior change consortium. Health Psychol. 2004;23:443–451. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farinati F, Sergio A, Baldan A, et al. Early and very early hepatocellular carcinoma: when and how much do staging and choice of treatment really matter? A multicenter study. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:33–45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuo Y, Lu SN, Chen CL, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance and appropriate treatment options improve survival for patients with liver cirrhosis. Euro J Cancer. 2010;46:744–751. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steel JL, Geller D, Carr BI. Proxy ratings of health related quality of life in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1025–1033. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-3267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sneeuw KC, Aaronson NK, Osoba D, et al. The use of significant others as proxy raters of the quality of life of patients with brain cancer. Med Care. 1997;35:490–506. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199705000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sneeuw KC, Aaronson NK, Sprangers MA, et al. Value of caregiver ratings in evaluating the quality of life of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1206–1217. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deschler DG, Walsh K, Friedman S, et al. Quality of life assessment in patients undergoing head and neck surgery as evaluated by lay caregivers. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:42–46. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199901000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collins LM, Murhphy SA, Strecher V. The Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) and the Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial (SMART): new methods for more potent e-health interventions. Am J Prev Med. 32:S112–S118. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rhee Y, Degenholtz H, Lo Sasso AT, Emanuel LL. Estimating the quantity and economic value of family caregiving for community-dwelling older persons in the last year of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1654–1659. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weitzner MA, McMillan SC. The Caregiver Quality of Life Index-Cancer (CQOLC) Scale: revalidation in a home hospice setting. J Palliat Care. 1999;15:13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the caregiver health effects study. JAMA. 1999;282:2215–2219. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cherlin EJ, Barry C, Prigerson HG, et al. Bereavement services for family caregivers: how often used, why, and why not. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:148–158. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bergman EJ, Haley W. Depressive symptoms, social network, and bereavement service utilization and preferences among spouses of former hospice patients. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:170–176. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measure. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tittle MB, McMillan SC, Hagan S. Validating the brief pain inventory for use with surgical patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum Online. 2003 Mar-Apr;30:325–330. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.325-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, et al. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the functional assessment of cancer therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;3:63–74. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heffernan N, Cella D, Webster K, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life in patients with hepatobiliary cancers: the functional assessment of cancer therapy-hepatobiliary questionnaire. J Clin Oncol. 2002 May 1;20:2229–2239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marteau TM, Bekker H. The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) Br J Clin Psychol. 1992 Sep;31(Pt 3):301–306. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1992.tb00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, III, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989 May;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clayton AH, McGarvey EL, Clavet GJ. The changes in sexual functioning questionnaire (CSFQ): development, reliability, and validity. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33:731–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kristjanson LJ. Validity and reliability testing of the FAMCARE Scale: measuring family satisfaction with advanced cancer care. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36:693–701. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90066-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, et al. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy–Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp) Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:49–58. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, Weinman J. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2006 Jun;60:631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Watson M, Greer S. Development of a questionnaire measure of emotional control. J Psychosom Res. 1983;27:299–305. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(83)90052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a re-evaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Theut SK, Jordan L, Ross LA, Deutsch SI. Caregiver’s anticipatory grief in dementia: a pilot study. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1991;33:113–118. doi: 10.2190/4KYG-J2E1-5KEM-LEBA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vrana S, Lauterbach D. Prevalence of traumatic events and post-traumatic psychological symptoms in a nonclinical sample of college students. J Trauma Stress. 1994 Apr;7:289–302. doi: 10.1007/BF02102949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1996 Jul;9:455–471. doi: 10.1007/BF02103658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]