Abstract

Peripheral activation of corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 2 (CRF2) by urocortin 1, 2, or 3 (Ucns) exerts powerful effects on gastric function; however, little is known about their expression and regulation in the stomach. We investigated the expression of Ucns and CRF2 isoforms by RT-PCR in the gastric corpus (GC) mucosa and submucosa plus muscle (S+M) or laser captured layers in naive rats, their regulations by lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 100 μg/kg ip) over 24 h, and the effect of the CRF2 antagonist astresssin2-B (100 μg/kg sc) on LPS-induced delayed gastric emptying (GE) 2-h postinjection. Transcripts of Ucns and CRF2b, the most common wild-type CRF2 isoform in the periphery, were expressed in all layers, including myenteric neurons. LPS increased Ucn mRNA levels significantly in both mucosa and S+M, reaching a maximal response at 6 h postinjection and returning to basal levels at 24 h except for Ucn 1 in S+M. By contrast, CRF2b mRNA level was significantly decreased in the mucosa and M+S with a nadir at 6 h. In addition, CRF2a, reportedly only found in the brain, and the novel splice variant CRF2a-3 were also detected in the GC, antrum, and pylorus. LPS reciprocally regulated these variants with a decrease of CRF2a and an increase of CRF2a-3 in the GC 6 h postinjection. Astressin2-B exacerbated LPS-delayed GE (42–73%, P < 0.001). These data indicate that Ucn and CRF2 isoforms are widely distributed throughout the rat stomach and inversely regulated by immune stress. The CRF2 signaling system may act to counteract the early gastric motor alterations to endotoxemia.

Keywords: Astressin2-B, laser capture microdissection, lipopolysaccharide, myenteric neurons, upper gut

the 41-amino-acid peptide corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) was originally characterized as the hypothalamic neurohormone primarily responsible for the stimulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis during stress (62). Subsequently, CRF was demonstrated to serve as a trans-synaptic signal in the brain contributing to the stress-related behavioral, autonomic, and visceral (cardiovascular and gastrointestinal) responses in rodents and monkeys (21, 25, 54). In addition to CRF, three CRF-related peptides, including urocortin 1 (Ucn 1), urocortin 2 (Ucn 2), and urocortin 3 (Ucn 3), were characterized in rodents and humans (24, 48) and shown to be prominently expressed in peripheral tissues where they influence visceral function (17, 43, 57). CRF and Ucn actions are mediated through two G protein-coupled seven-transmembrane domain receptors, CRF1 and CRF2, that display distinct affinities for the CRF-related ligands (24). CRF1 receptor has high affinity for Ucn 1 or CRF and no appreciable binding affinity for Ucn 2 and Ucn 3. CRF2 receptor binds Ucn 1, Ucn 2, and Ucn 3 with high affinity but interacts poorly with CRF at a 40-fold lower affinity, making this receptor subtype highly selective for Ucn signaling (17, 24). In rodents, CRF2 exists in two protein-coding slice variants, CRF2a and CRF2b (previously denoted as CRF2α and CRF2β, respectively), that are highly conserved among mammalian species, including humans (24). Although these variants are structurally distinct in their NH2-terminal extracellular domains, they share similar high affinity for Ucns (24). In rats, CRF2a was originally reported to be only expressed in brain neurons while CRF2b is expressed mainly in the periphery and nonneuronal cells of the brain (41). However, our previous studies indicate that multiple CRF2a splice variants are also expressed in the rat esophagus although less abundantly than the CRF2b isoform (67).

Convergent functional studies established that peripheral administration of Ucn-induced inhibition of gastric motor function and food intake involves the activation of peripheral CRF2 receptors in rodents (20, 43, 49, 65). This was supported by the blockade of peripherally injected Ucn-induced inhibition of gastric emptying, antral contractions and food intake by the selective CRF2 antagonist astressin2-B (52) injected intraperitoneally while intracerebroventricular injection of astressin2-B or peripheral injection of CRF1 receptor antagonist crossing the blood-brain barrier have no effect (16, 44, 45, 49, 65). Last, peripheral injection of astressin2-B or astressin prevents acute partial restraint or abdominal surgery-induced delayed gastric emptying of a solid meal in rats as assessed within the first hour of the stress procedure (42, 44). These data provide convergent pharmacological evidence for a role of peripheral Ucns/CRF2 signaling pathways in the alterations of gastric propulsive motor function induced by acute exposure to physical/visceral stressors. However, contrary to the wealth of functional studies on the actions of Ucns and potential relevance of Ucns/CRF2 signaling in the stomach in experimental animals and humans (3, 10, 33, 69), little is known about the expression and regulation of Ucn ligands and CRF2 receptors within the various gastric corpus (GC) layers compared with reports in other gut segments (7, 8) or visceral organs such as the heart (31).

Bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is widely used to study the innate defense response to Gram-negative bacteria infection, inducing immunological stress (37). LPS injected at a low dose delayed gastric emptying (64), which is considered as part of the systemic symptoms of infection related to “acute-phase responses” (55). Recent studies also indicate that CRF2b and Ucn 1 mRNA expression in the peripheral organs such as the pituitary, heart, thymus, or spleen are differentially regulated by LPS (30–32). It is still unknown whether LPS regulates Ucns/CRF2 gene expression in the rat stomach although functional studies indicate that the stomach is a target for CRF2-mediated actions of Ucns to influence gastric motor function and to exert an anti-inflammatory effect (9, 43).

In the present study, we first examined the gene expression profile of Ucns and CRF2b, the most common wild-type receptor isoform of CRF2 found in peripheral tissues (41), in the GC mucosa and submucosa plus muscle (S+M) layers in naïve rats. Next, we delineated the expression of Ucns and CRF2b in multiple defined layers of the GC, including myenteric neurons, using the laser capture microdissection (LCM) system combined with reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The regulation of Ucns/CRF2b gene expression in the gastric mucosa and S+M over a 24-h period was assessed following LPS injected intraperitoneally at a single dose of 100 μg/kg previously established to reduce gastric emptying (4, 19, 64), mimicking some of the clinical features of acute Gram-negative bacterial infection without apparent signs of severe sickness found in endotoxin shock induced by milligram doses of LPS (38). Previously, we identified in the rat esophagus and lower esophagus sphincter (LES) the novel CRF2 splice variant CRF2a and the other related isoform CRF2a-3, which contains the entire intron 3 (67). We determined whether these splice variants are also expressed in various regions of the stomach (corpus, antrum, and pylorus) and regulated by LPS. Last, the role of CRF2 activation in the early phase of LPS-induced delayed gastric emptying was investigated by pharmacological blockade of CRF2 receptors by astressin2-B before LPS injection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Laboratory, San Diego, CA) weighing 260–310 g were housed under controlled conditions of temperature and lighting (22–24°C, light on from 6:00 A.M. to 6:00 P.M.). Animals had free access to Purina Rat Chow (Ralston Purina, St. Louis, MO) and tap water. Studies were conducted under the approved protocol of the Department of Veterans Affairs Animal Component of Research Animal Research Committee (no. 05–058-02). All experiments were performed between 7:00 and 10:00 A.M. except for in the 6- and 9-h time course study, which ended at 1:00 P.M. and 4:00 P.M., respectively.

Ucns and CRF Receptor Gene Expression in the GC of Naïve Rats

Tissue collection.

Four naïve rats were euthanized by decapitation, and two samples of GC were harvested from each rat. One sample of GC was taken as the whole thickness, and the other was separated into mucosa and S+M layers. Other tissues known to express high mRNA levels of CRF1 (cerebral cortex) (63) and CRF2b (heart, left ventricle) (34, 47) were also harvested and used as positive controls. All tissue samples were immediately frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C until processed for RNA extraction and RT-PCR determinations.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR.

Tissue samples were homogenized in RNA-Bee (TEL-TEST, Friendswood, TX) using a Polytron homogenizer (Brinkmann Instruments, Westbury, NY) following the manufacturer's recommended protocol. RNA pellets were resuspended in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water and further digested with DNase I for 60 min at 37°C (Promega, Madison, WI). The quality and amount of RNA samples were estimated based on the ratio of absorbance at 260/280 nm by an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (ND-1000; NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE). Next, 5 μg of total RNA were reverse transcribed to cDNA using ThermoScript reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in a total volume of 20 μl reaction buffer. The reaction was terminated by incubation at 85°C for 5 min. One microliter of RNase H was added to the reaction mixture to remove the RNA template. Subsequently, 1 μl of first-strand cDNA was amplified directly by the PCR as described previously (67). The sequences of primers specific for rat Ucn 1, Ucn 2, Ucn 3, CRF1, and CRF2b receptors are listed in Table 1. Rat CRF receptor primers were designed to amplify the specific NH2-terminal-specific region of CRF1 and CRF2b. RT-PCR for acidic ribosomal protein (ARP), a housekeeping gene, served as an internal control to assess RNA quality and cDNA normalization. PCR products were separated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, visualized with ethidium bromide. Gel images were acquired by the Kodak EDAS 290 system, and quantitative densitometry was performed with NIH Image software (Scion, Frederick, MD).

Table 1.

Rat primers used for RT-PCR experiments

| Genes | Direction | cDNA Primer (5′-3′) | Position | Product Size, bp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ucn 1 | Forward | GCTACGCTCCTGGTAGCGTTGCTGCTTCTG | 133–162 | 356 |

| Reverse | GCCGATCACTTGCCCACCGAGTCGAATATG | 459–488 | ||

| Ucn 2 | Forward | ATGATGACCAGGTGGGCACTG | 85–105 | 367 |

| Reverse | AGGTCACCCCATCTTTATGAC | 431–451 | ||

| Ucn 3 | Forward | AGCGATGCTGATGCCCACTTAC | 505–526 | 515 |

| Reverse | CCTGCCTGGTCTTTGCTTTATTTC | 997–1020 | ||

| CRF1 | Forward | CTCTGGGATGTCGGAGCGATCCA | 23–45 | 439 |

| Reverse | CAGTGACCCAGGTAGTTGAT | 442–461 | ||

| CRF2a and CRF2a-3 | Forward | GCGGCCCCTCATCTCCGTGAG | 1–22 | 353, 483* |

| Reverse | CTGGTCCAAGGTCGTGTTGCA | 333–353 | ||

| CRF2b | Forward | ATGGGGACCCCAGGCTCT | 215–232 | 198 |

| Reverse | CTGGTCCAAGGTCGTGTTGCA | 392–412 | ||

| PGP 9.5 | Forward | ATGAATCAGACCATCGGGAAC | 227–297 | 505 |

| Reverse | GCTAAAGCTGCAAACCAAGGG | 761–781 | ||

| ARP | Forward | GTTGAACATCTCCCCCTTCTC | 604–624 | 402 |

| Reverse | ATGTCCTCATCGGATTCCTCC | 85–1005 |

Ucn, urocortin; CRF, corticotropin-releasing factor; PGP, protein gene product; ARP, acidic ribosomal protein.

Variant CRF2a-3 (including intron 3).

LCM.

Two naïve rats were decapitated, and whole-thickness GC tissues were sectioned vertically or flatly in a cryostat at 8 μm, mounted on SuperFrost slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), air-dried, fixed in 70% ethanol, and then rehydrated in DEPC-treated water. Vertical sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Flat sections across the myenteric plexus were stained with cuprolinic blue, an established histochemical staining specific for enteric neurons (26). Different layers of the GC and myenteric neurons were dissected using the Pixcell II Laser Capture Microdissection System installed in an Olympus microscope (Arcturus Engineering, Mountain View, CA). The laser was set to a laser beam of 7.5 μm in diameter with laser power at 50 mW. Images were taken by the PixCell II Image Archiving Workstation before and after transfer. For each rat, samples were captured from ∼50 shots/layer or 50 neurons on the CapSure LCM caps (Arcturus) and immersed in RNA extraction solution.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR for LCM-captured samples.

The adherent tissue on the LCM caps was incubated with RNA-Bee at room temperature for 20 min to digest the tissue off cap. Chloroform was then added, and the solution was centrifuged for 15 min at 4°C. The aqueous layer was precipitated with isopropanol, and the RNA pellet was suspended in DEPC water and digested for 60 min at 37°C using DNase I (Promega). After final recovery and resuspension, extracted RNA from each layer was pooled from the two animals, and 200 ng of total RNA were denatured at 65°C for 5 min and then reverse transcribed to cDNA using ThermoScript reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) in a total volume of 20 μl reaction buffer. PCR for LCM-captured samples and control tissues from cerebral cortex and left heart ventricle were processed as described above. PCR for protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5), a pan-neuronal marker (36), was carried out to ascertain the neuronal identity of captured myenteric cells. Negative control contained all reagents, except that 1 μl H2O was substituted for reverse transcriptase in the RT reaction to exclude the possibility of genomic or other DNA contamination. All PCR products corresponding to predicted rat CRF1 and CRF2b receptors, Ucn 1, Ucn 2, and Ucn 3 were separated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, visualized with ethidium bromide, extracted with the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA), and sequenced to confirm their identities as previously described (67).

Influence of LPS on Ucns and CRF2b Receptor Gene Expression in the GC

Ten groups of conscious rats (4–5/group) were injected intraperitoneally (0.3 ml) with either vehicle (sterile saline) or LPS (100 μg/kg, Escherichia coli serotype O26:B6; code 3755, lot 37H4095; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) and then euthanized by decapitation at 1, 2, 6, 9, and 24 h after the intraperitoneal injection. Another group of nontreated rats (n = 4) was used as a naïve control and killed at the beginning of the experiment. The stomach was removed, and the GC was collected as whole thickness, separated in mucosa and S+M, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C for 1–4 days until RNA extraction. RT-PCR for Ucn 1, Ucn 2, Ucn 3, CRF1, and CRF2b mRNA levels and quantitative analysis were performed as described above.

Detection of CRF2a Receptor Gene Expression in Various Stomach Regions and Regulation by LPS in the GC

Four naïve rats were killed by decapitation, and the distal esophagus, LES, GC, antrum, and pylorus were harvested. Another two groups (5 rats/group) were injected intraperitoneally (0.3 ml) with either saline or LPS (100 μg/kg), and the GC was harvested 6 h later corresponding to the peak changes based on previous time course study. GC mucosa and S+M were separated. All tissue samples were processed to assess CRF2a mRNA expression after total RNA extraction as described above using the primers designed to amplify the NH2-terminal-specific region of CRF2a (Table 1).

Effects of the CRF2 Antagonist Astressin2-B on LPS-Induced Delayed Gastric Emptying

Four groups of rats (6 rats/group) were pretreated subcutaneously (0.3 ml/rat) with astressin2-B (100 μg/kg dissolved in distilled water; Clayton Foundation Laboratories, Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA) or vehicle (distilled water) 15 min before the intraperitoneal injection (0.3 ml) of LPS (100 μg/kg) or vehicle (saline). Two hours after the intraperitoneal injection, gastric emptying of a nonnutrient viscous solution (1.5 ml/oral gavage of 1.5% methyl cellulose mixed with 0.05% phenol red) was determined as previously described (45) in all rats that were euthanized by decapitation 20 min after oral gavage. The percent emptying of the solution from the stomach during the 20-min period was calculated according to the following equation: % emptying = 1 − (absorbance of test sample/absorbance of standard) × 100 (45). The dose and route of astressin2-B administration was based on our previous studies showing full prevention of intravenous Ucn 2 and partial restraint-induced delayed gastric emptying in rats (44).

Statistical Analyses

In all studied samples, the band intensity of each targeted PCR product was normalized to its corresponding ARP, the reference gene, and results were expressed in corrected arbitrary units. Levels of Ucns and CRF2b receptor mRNA in the GC mucosa were compared with those in the S+M in naïve rats by Student's t-test. Changes in CRF2a mRNA levels induced by LPS at 6 h postinjection compared with intraperitoneal vehicle were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, and post hoc comparisons were performed by Dunnett's multiple-comparison test. In the 24-h time course study, the normalized values were expressed as percent of naïve control, which was defined as 100%, and data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with LPS treatment and time as fixed factors followed by post hoc comparisons using Bonferroni's method. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Gastric emptying data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Dunnett's post hoc comparison test.

RESULTS

Ucn and CRF Receptor Gene Expression in the GC of Naïve Rats

GC mucosa vs. S+M layers.

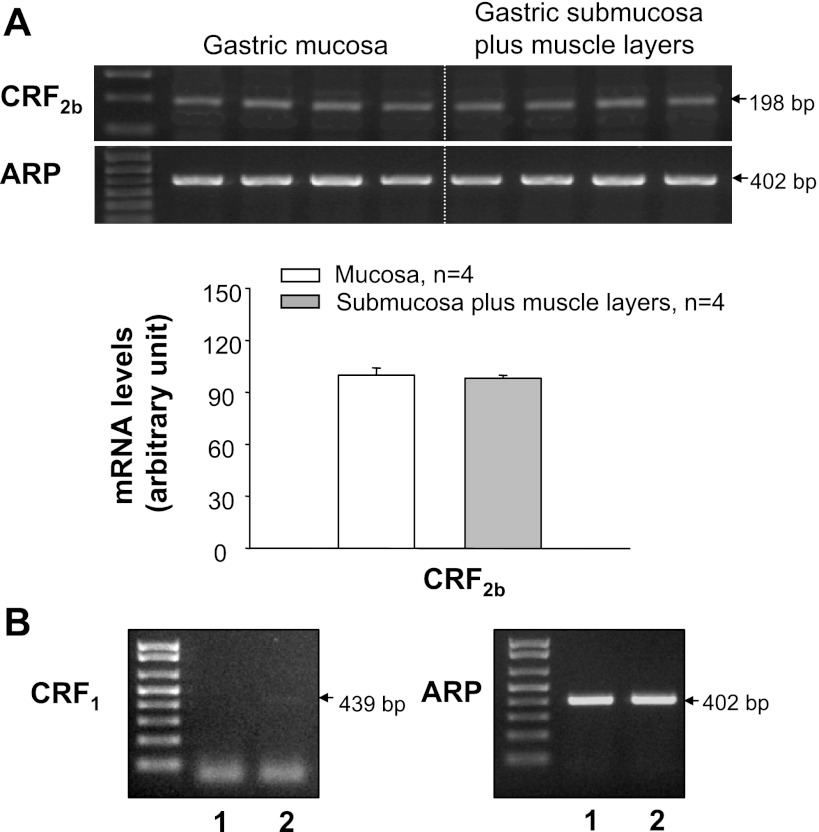

A band with similar intensity for the PCR product of ARP at the predicted size was detected in the GC tissues separated into mucosa and S+M layers in all samples, confirming RNA quality (Fig. 1A). Using primers specific for rat Ucns and CRF receptors, we showed that Ucn 1 and Ucn 3 mRNA levels were significantly higher in the GC mucosa than in S+M, whereas there was no significant difference between the two layers for Ucn 2 mRNA levels (Fig. 1, A and B). CRF2b transcript was detected in both the GC mucosa and S+M with similar gene expression levels (Fig. 2A). Compared with CRF2b, CRF1 transcript was detected, with a much weaker band in the GC S+M, and no gene expression was found in the mucosa from the samples pooled from four rats (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 1.

Urocortin (Ucn) 1, Ucn 2, and Ucn 3 gene expression in the gastric corpus mucosa and submucosa plus muscle (S+M) layers of naïve rats. A: gel image of RT-PCR products showing predicted Ucn 1 (356 bp), Ucn 2 (367 bp), Ucn 3 (516 bp), and housekeeping gene acidic ribosomal protein (ARP) (402 bp). B: semiquantitative analysis of Ucns in gastric mucosa and S+M layers. Values are expressed as the corrected mRNA levels in arbitrary units, and each column represents the mean ± SE of 4 rats. *P < 0.05, significant difference between mucosa and S+M layers.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) receptor gene expression in the rat gastric corpus mucosa and S+M layers of naïve rats. A: top, gel images of RT-PCR products showing the predicted band of CRF2b detected in both mucosa and S+M with similar expression levels. Bottom, semiquantitative analysis. Values are expressed as corrected mRNA levels in arbitrary units, and each column represents the mean ± SE of 4–5 rats. B: gel images of RT-PCR showing that the CRF1 band with very low intensity was only found in S+M but not in the mucosa in the gastric corpus samples pooled from 4 rats (lane 1, mucosa; lane 2, S+M).

GC various layers obtained by LCM.

With the use of LCM, the surface epithelia, neck zone, glandular middle portion, glandular basal portion, submucosa, and circle and longitudinal muscle layers were separately obtained from the vertical sections (Fig. 3C) of the whole-thickness GC (Fig. 3A), leaving the untargeted tissues attached to the glass slide (Fig. 3B). As a result, the morphology of the transferred tissues was preserved and could be readily visualized under a microscope (Fig. 3C). PCR products of the housekeeping gene ARP were detected with the predicted size and similar intensity in all layers (Fig. 3D), indicating the high-quality and consistency of cDNA made from the total RNA originating from LCM-dissected GC samples. The negative control showed no discernible PCR signal, indicating no genomic or other DNA contamination in the cDNA (data not shown). Ucn 1 and Ucn 3 transcripts were positively identified from the glandular middle portion, submucosa, muscle layers, epithelia, and neck zone, albeit a faint band was found in the glandular basal portion for Ucn 1 (Fig. 3D). Strong bands for Ucn 2 PCR product were found mainly in the glandular middle portion and muscle layers (Fig. 3D). CRF2b mRNA was detected in all layers, showing a general expression pattern similar to those of Ucn 1 and Ucn 3 (Fig. 3D). All PCR products were sequenced and found to be identical to the corresponding known sequences of rat Ucn 1, Ucn 2, Ucn 3, and CRF2b, except for CRF1 mRNA, which was undetectable in these samples (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Laser capture microdissection (LCM) of freshly frozen vertical sections (8 μm) of gastric corpus stained with hematoxylin and eosin in naïve rats. The surface epithelia, neck zone, glandular middle portion, glandular basal portion, submucosa, and circle and longitudinal muscle layers were collected separately from the whole-thickness tissue sections; untargeted tissues remained attached to the glass slide. A: before transfer. B: after transfer. C: transferred tissue samples. Bar = 100 μm. D: gel images of RT-PCR products for Ucn 1, Ucn 2, Ucn 3, CRF2b, and ARP in 7 laser-captured samples from the gastric corpus. LCM samples were pooled from 2 rats.

In the flat sections of GC across myenteric plexus, the cytoplasm of individual myenteric neurons stained with cuprolinic blue were clearly defined, with the blue-stained Nissl substance forming a ring around the unstained nucleus while the dendrites and processes of the neurons lacked staining (Fig. 4A). With the use of LCM, the cuprolinic blue-stained cells were precisely captured (Fig. 4, B and C). The PCR product for PGP 9.5 was detected from the captured myenteric cells, confirming their neuronal identities. GC myenteric neurons display bands of the predicted PCR products for Ucn 1, Ucn 2, Ucn 3, CRF1, and CRF2b (Fig. 4D). As positive controls, the PCR products for CRF1 in cerebral cortex, CRF2b in heart, and Ucn 1, Ucn 2, and Ucn 3 in the GC were clearly detected at their expected sizes (Fig. 4E). The negative control showed no band (data not shown). All PCR products were sequenced and found to be identical to the corresponding known sequences of rat Ucn 1, Ucn 2, Ucn 3, and CRF1 and CRF2b receptors.

Fig. 4.

LCM of freshly frozen flat sections (8 μm) across the gastric corpus myenteric plexus stained with cuprolinic blue in naïve rats. Individual myenteric neurons were clearly defined with blue staining while dendrites and processes of the neurons lacked staining. With the use of LCM, the cuprolinic blue-stained cells were precisely captured. A: before transfer. B: after transfer. C: transferred tissue samples. Bar = 100 μm. D: RT-PCR analysis showing that transcripts of Ucn 1, Ucn 2, Ucn 3, CRF1, and CRF2b were detected in gastric myenteric neurons expressing protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5). E: positive controls showing Ucn 1, Ucn 2, and Ucn 3 in the rat gastric corpus, CRF1 in the rat cerebral cortex, and CRF2b in the rat heart. The negative control showed no band (data not shown). LCM samples were pooled from 2 rats.

Regulation of Ucn 1, Ucn 2, Ucn 3, and CRF2b Isoform Gene Expression in the GC by LPS

Ucn 1, Ucn 2, and Ucn 3 mRNA levels remained stable in the gastric mucosa and S+M layers at 1, 2, 6, 9, and 24 h postintraperitoneal injection of vehicle, and values were similar to those of naïve rats (Fig. 5). In the mucosa, LPS (100 μg/kg ip) induced a significant time-related (2–9 h) increase in mRNA levels of Ucn 1 (55–46%), Ucn 2 (77–102%), and Ucn 3 (38% at 6 h), whereas there were no significant changes at 1 and 24 h post-LPS injection compared with values in the respective intraperitoneal vehicle groups (Fig. 5, A–C). Likewise, in the S+M, there was no significant change at 1 h post-LPS injection, and then mRNA levels rose significantly compared with time-related vehicle to 75–119% at 2–24 h for Ucn 1, 73% at 6 h for Ucn 2, and 50–40% at 2–9 h for Ucn 3, with peak values occurring at 6 h. Thereafter, values declined back to the control except for Ucn 1 mRNA (Fig. 5, D–F). A two-way ANOVA indicates a main effect of intraperitoneal injection of LPS over vehicle on the GC expression of Ucn 1 in the mucosa [F(1,48)=6.5, P < 0.05] and S+M [F(1,48)=38.7, P < 0.001], Ucn 2 in the mucosa [F(1,48)=5.2, P < 0.05] and Ucn 3 in the S+M [F(1,48)=10.7, P < 0.01]. There was also a main effect of time on the expression of Ucn 1 [F(5,48)=3.7, P < 0.01], Ucn 2 [F(5,48)=5.7, P < 0.001], and Ucn 3 [F(5,48)=5.3, P < 0.001] in the mucosa and Ucn 1 [F(5,48)=4.4, P < 0.01] and Ucn 3 [F(5,48)=3.5, P < 0.01] in the S+M. Two-way interactions involving intraperitoneal injection of LPS × time were also significant for gene expression of Ucn 1 [F(5,48)=3.1, P < 0.05] in the S+M, Ucn 2 [F(5,48)=2.9, P < 0.05] in the mucosa [F(5,48)=3.8, P < 0.01] and the S+M, and Ucn 3 [F(5,48)=2.6, P < 0.05] in the mucosa.

Fig. 5.

Time course of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced upregulation of Ucn 1, Ucn 2, and Ucn 3 gene expression in the rat gastric corpus mucosa and S+M layers. Groups of rats (n = 4–5) were injected ip (0.3 ml) with saline or LPS (100 μg/kg) and euthanized at various time intervals. Naïve rats (n = 4) were used as control at time 0. The gel images of PCR products were semiquantified by densitometry. The results were normalized to the housekeeping gene ARP and expressed as a percent of control, which was defined as 100%. Each column represents the mean ± SE of 4–5 rats as indicated. P < 0.05 compared with the control group (*) and with the respective vehicle group (#). A–C: mucosa. D–F: S+M layers. A and D: Ucn 1. B and E: Ucn 2. C and F: Ucn 3.

In contrast to Ucns, CRF2b mRNA levels were significantly decreased by 57 and 70% in the mucosa at 6 and 9 h (Fig. 6A) and by 38, 53, 55, and 43% in M+S at 1, 2, 6, and 9 h, respectively, after LPS injection compared with time-related vehicle groups (Fig. 6B). Saline injection did not significantly alter CRF2b mRNA levels in the GC mucosa (Fig. 6A) or S+M (Fig. 6B) when monitored at 1, 2, 6, 9, and 24 h postinjection when compared between the different time periods and the noninjected group. At 24 h post-LPS injection, CRF2b mRNA levels in the mucosa were back to those of the intraperitoneal vehicle-injected group (Fig. 6A) while being still significantly inhibited in the S+M layers (Fig. 6B). A two-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect of LPS over vehicle for CRF2b in the corpus mucosa [F(1,48) = 4.4, P < 0.05] and S+M [F(1,46) = 41.7 P < 0.001] and also a main effect of time in the S+M [F(5,48) = 20.9, P < 0.001]. The interaction between LPS × time was also significant for CRF2b in the mucosa [F(5,48) = 3.4, P < 0.01] and the S+M [F(5,48) = 8.6, P < 0.01].

Fig. 6.

Time course of LPS-induced downregulation of CRF2b gene expression in both mucosa and S+M layers. Data were collected from the same experiment as described in Fig. 5. Each column represents the mean ± SE of 4–5 rats as indicated. P < 0.05 compared with the control group (*) and with the respective vehicle group (#). A: mucosa. B: S+M layers.

CRF2a Gene Expression in the Rat Stomach and Regulation by LPS

CRF2a mRNA levels in the esophagus and various regions of the stomach.

The PCR product for CRF2a at the expected size of 353 bp was detected in all regions of the stomach; however, levels were 6.2-, 6.3-, and 10-fold lower in the GC, antrum, and pylorus than in the distal esophagus/LES, respectively (Fig. 7A). In addition, another product at 483 bp was found on the gel with stronger intensity compared with that at 353 bp (Fig. 7A). This product was identified and confirmed by sequencing as one of the novel CRF2a splice variants (CRF2a-3) that we previously identified in rat esophagus (67). The level of CRF2a-3 gene expression is similar among the GC, antrum, and pylorus and significantly higher than in the distal esophagus (2.6-fold) and LES (1.5-fold). Levels of CRF2a-3 compared with wild-type CRF2a were significantly higher in the GC (5.4-fold), antrum (5.3-fold), and pylorus (10-fold) and significantly lower in the distal esophagus (3.1-fold) and LES (1.8-fold) (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

Expression patterns of CRF receptor subtypes in the rat upper gut. A–C: top, gel images of RT-PCR amplified CRF receptor transcripts. Bottom: semiquantitative analysis. The values are expressed as corrected arbitrary units, and each column represents the mean ± SE of 4 rats. A: CRF2a. The band for CRF2a at the expected size of 353 bp was detected in the distal esophagus (E), lower esophagus sphincter (LES), and various regions of the stomach, including gastric corpus (GC), antrum (A), and pylorus (Py). In addition, a larger band of 483 bp in size was found with stronger intensity compared with that at 353 bp. This product was confirmed by sequencing as a splicing variant of CRF2a and CRF2a-3 previously found in rat esophagus (67). P < 0.05 compared with CRF2a value in E (*), with CRF2a-3 values in E (&), and with CRF2a values in E, LES, GC, A, and Py (@). B: CRF2b. P < 0.05 compared with the values in E (*) and with the values in GC (#). C: CRF1. P < 0.05 compared with the values in E (*) and compared with the values in GC (#).

CRF2b mRNA levels in the esophagus and various regions of the stomach.

CRF2b mRNA levels were significantly 4.8-fold lower in the GC and 2-fold lower in the antrum and pylorus compared with those in the distal esophagus/LES (Fig. 7B). Comparison within the various gastric regions showed that CRF2b mRNA levels in the antrum and pylorus were 3.2-fold higher than in the corpus (Fig. 7B). CRF1 mRNA is expressed in both the antrum and pylorus with a significantly higher level than either the esophagus or GC where it was undetectable, and low expression was found in the LES (Fig. 7C).

Regulation of CRF2a gene expression in the GC by LPS.

We then assessed the influence of LPS on CRF2a isoforms at 6 h post-LPS injection corresponding to maximal changes observed in CRF2b gene expression (Fig. 6). CRF2a mRNA was decreased by 84% in the mucosa (Fig. 8, A and C) and 90% in the S+M of the GC (Fig. 8, B and D), whereas CRF2α-3 was significantly increased by 40% in the mucosa (Fig. 8, A and C) and 118% in the M+S of GC (Fig. 8, B and D).

Fig. 8.

Expression of CRF2a and CRF2a-3 in gastric corpus mucosa and S+M layers and LPS induced regulation of CRF2a and CRF2a-3 gene expression at 6 h postinjection. A and C: gastric corpus mucosa. B and D: gastric corpus S+M layers. Rats were injected ip (0.3 ml) with saline or LPS (100 μg/kg) and euthanized 6 h thereafter. CRF2a and CRF2a-3 in the rat gastric corpus were inversely regulated by LPS. The results were normalized to the housekeeping gene ARP and expressed as percent of CRF2a-3 in the vehicle group (100%) in the mucosa. Each column represents the mean ± SE of 5 rats. P < 0.05 compared with CRF2a (*), with CRF2a-3 (#) in the vehicle group in the mucosa, with CRF2a (@), and with CRF2a-3 (+) in S+M in the vehicle group.

Effects of CRF2 Receptor Blockade on LPS-Induced Delayed Gastric Emptying

In subcutaneous vehicle-pretreated rats, LPS (100 μg/kg ip) decreased gastric emptying of a viscous solution compared with subcutaneous vehicle + intraperitoneal vehicle (LPS: 39.3 ± 4.3% vs. vehicle: 67.5 ± 7.9%, P < 0.001) as monitored during the 120 to 140 min period postintraperitoneal injection (Fig. 9). Pretreatment with astressin2-B (100 μg/kg sc 15 min before LPS) further enhanced LPS-induced delayed gastric emptying (18.2 ± 3.2% vs. vehicle/vehicle: 67.1 ± 4.6%, P < 0.001; vs. vehicle/LPS: 39.3 ± 4.3%, P < 0.001) (Fig. 9). Astressin2-B in the intraperitoneal vehicle-treated group did not influence basal gastric emptying (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

The CRF2 antagonist astressin2-B enhanced LPS-induced delayed gastric emptying. Overnight-fasted rats were injected sc (0.3 ml) with astressin2B (100 μg/kg) or vehicle (distilled water) 15 min before ip injection of LPS (100 μg/kg) or saline. Rats received an orogastric gavage of a nonnutrient solution (1.5 ml) 2 h after ip injection, and gastric emptying was assessed 20 min later. Each bar represents the mean ± SE of 6 rats. P < 0.001 vs. sc vehicle/ip vehicle (***), vs. sc astressin2B/ip vehicle (###), and vs. sc vehicle/ip LPS (+++).

DISCUSSION

The present study provides evidence that transcripts for the three Ucns and multiple CRF2 isoforms are expressed in various laser-captured layers of the rat GC, most prominently in the myenteric neurons, whereas gastric CRF1 mRNA levels are low or undetectable. In addition, we identified the presence of CRF2a and more abundantly CRF2a-3, an intron 3-containing splice variant in the GC, antrum, and pylorus. Of significance was the regulation of Ucns/CRF2 gene expression in both the GC mucosa and S+M layers induced by a low dose of LPS, leading to the upregulation of all three Ucn ligands and downregulation of both wild-type CRF2b and CRF2a receptors in a time-dependent manner. Interestingly, the splice variant corresponding to the CRF2a-3 isoform was inversely upregulated. Last, we showed that blockade of CRF2 receptor potentiates the delayed gastric emptying induced by LPS.

Distribution of Ucns in the GC of Naïve Rats

Thus far, knowledge on the gene expression of Ucns in the rodent stomach has been limited, and not all three Ucns have been concurrently assessed. In the whole rat stomach, Ucn 1 transcript expression was detected by hybridization histochemistry, RNase protection assay, or RT-PCR in most studies (5, 7, 30) except one (22). Ucn 2 mRNA was consistently found in mice and rat whole stomach or rat antrum by RT-PCR analysis (12, 49, 68). In the present study, we provide evidence that Ucn 1 mRNA is expressed in the rat GC mucosa at a more prominent level than in the S+M layers. We also found Ucn 2 mRNA levels were equally distributed in the mucosal and submucosal muscle layers of the GC, expending a previous report showing similar Ucn 2 mRNA levels in both mucosa and muscle layers in the rat antrum (49). Ucn 3 mRNA was similarly expressed in GC as Ucn 1, albeit more prominently in the mucosa vs. the submucosal muscle layers. Ucn 3 gene expression has been shown previously in the rat and mice pancreas (39, 40). Here we provide the first evidence of its expression in the rat stomach. In humans, the expression of Ucn 1 was demonstrated by RT-PCR analysis of biopsies from human antrum mucosa (9) and that of Ucn 2 and Ucn 3 by PCR analysis of human cDNA from the whole stomach (27). Collectively, these data demonstrate that all three Ucns are expressed in both rat and human stomach, and their distributions include both the mucosa and S+M layers in the GC.

To better define the distribution of Ucn expression in the layer components of the GC, LCM combined with subsequent RT-PCR analysis revealed that Ucn 1 and Ucn 3 were widely expressed in all GC layers. The glandular middle portion of the mucosa expressed the highest levels of three Ucns, and Ucn 1 and Ucn 2 mRNA were also found prominently in muscle layers while Ucn 3 mRNA was also remarkably expressed in the neck zone. Furthermore, we characterized the mRNA expression of Ucns in laser-captured GC myenteric neurons identified by their prominent coexpression with the neuronal marker PGP 9.5 (36). The sequencing of PCR products ascertains that their identities matched to the known sequences of rat Ucn 1, Ucn 2, and Ucn 3. Previous detection of Ucns at the peptide level indicates that the whole stomach contains higher levels of Ucn 1 compared with other viscera as monitored by radioimmunoassay (46). In addition, cellular localization of Ucn 1 immunoreactivity was found in the parietal cells of rat GC and human gastric mucosa (9, 35), which is consistent with high gene expression observed in the glandular midportion of Ucn 1. In rat gastric antrum, Ucn 1 immunoreactivity is present in enterochromaffin cells and a subpopulation of myenteric neurons (49). The widespread distribution of Ucn 1 mRNA in various layers of the GC mucosa as well as in myenteric neurons coupled with reports on Ucn 1 immunoreactivity in gastric epithelial, endocrine, and neuronal cells in rats are indicative of gene transcription and protein synthesis and processing. Based on gastric Ucn 1 gene/protein expression, it can be speculated that Ucn 2 and Ucn 3 may be also expressed at the protein level in the various GC layers in which gene expression was detected.

Distribution of CRF2 Receptor Isoforms in the Rat Stomach

In view of an initial report of the predominance of CRF2b in the rat periphery (41), other CRF2 isoforms in the various layers of the GC have not been delineated so far. Here we showed an equal distribution of CRF2b in the mucosa and S+M layers as expected. In addition, we detected CRF2a-related transcripts in the rat GC with a higher expression in the S+M layers than that in the mucosa. This may reflect a preferential expression of CRF2a in myenteric neurons contained in the S+M layers. Indeed, it was previously established that, in rats, CRF2a is exclusively expressed in brain neurons, in contrast to the CRF2b isoform, which is the predominant form in nonneuronal brain and peripheral tissues (41). However, we found that the gene expression of the CRF2a-3 splice variant previously identified to contain an unspliced intron 3 (Genbank accession no. EF078963) and thus encoding a 144-amino-acid truncated receptor lacking all seven transmembrane domains (67) is prominently expressed in the gastric mucosa and S+M layers, reaching levels 16- and 4.1-fold higher than that of CRF2a, respectively. These data highlight the importance of probe specificity and selection in PCR analysis to distinguish wild-type vs. truncated forms of CRF2a splice variants. There is increasing evidence that truncated CRF receptors, while losing signaling or binding properties, may alter the functions of endogenous ligands or signaling by the wild-type receptors (14, 70). The abundant expression of CRF2a-3 mRNA in the GC may be indicative of a similar modulatory role that warrants investigations.

LCM study revealed that CRF2b mRNA is found in all GC layers in a distributive pattern similar to that of Ucn 1. In the myenteric neurons in particular, we identified the mRNA expression of CRF2b and a low level of CRF1 receptor mRNA. This provides evidence that CRF2b, initially thought to be expressed mainly in nonneuronal structures in the brain and periphery (41), can be found also in peripheral neurons. We further confirmed this finding under the same conditions by showing the expression of CRF1 in the rat cerebral cortex and CRF2b in the heart and esophagus, consistent with differential high expression of these receptors in these respective tissues (31, 63, 67). At the protein level, CRF2 immunoreactivity was detected in the submucosal blood vessels and entire length of the oxyntic gland, including parietal cells, as indicated by the colocalization with H-K-ATPase (11) as well as in myenteric neurons and in nerve fibers running parallel to smooth muscles in rat antrum (49).

The expression of CRF2 receptor isoforms CRF2b, CRF2a, and CRF2α-3 mRNA is not limited to the GC but is also widespread in the upper gut as shown by the simultaneous assessment in the whole thickness of the antrum, pylorus, esophagus, and LES. However, the CRF2b mRNA was detected at the highest levels in the esophagus compared with various regions of the stomach. Conversely, CRF2α-3 was low in the esophagus and prominently expressed at similar levels in whole thickness of GC, antrum, and pylorus with levels 5.4-, 5.3-, and 10-fold higher than the CRF2a, which had a low expression. This inverse relationship within the CRF2a transcript pool becomes apparent following the activation of CRF2a gene promoter by LPS, likely reflecting the state of alternative splicing to control mRNA processing. The ubiquitous expression of gastric CRF2a and CRF2b transcripts in the upper gut contrasts with that of CRF1 mRNA, which was detected in the antrum and pylorus at low levels and barely detectable in the GC and esophagus, consistent with our previous findings in the esophagus (67). The demonstration that Ucns/CRF2 are the dominant signaling pathway components expressed in the rat stomach extends to rodent a few reports in human stomach indicating that the Ucn/CRF2 system is prominently expressed in contrast to a subdued CRF/CRF1 system (9, 10). These data provide anatomical and molecular support for a local action of Ucns/CRF2 in the stomach through an autocrine/paracrine regulatory loop.

Regulation of GC Ucn/CRF2 System by Low Dose of Endotoxin

Next, we established whether the GC Ucn/CRF2 gene expression can be regulated by an immune stressor. Our data showed that LPS injected intraperitoneally at 100 μg/kg elicited a significant time-dependent increase in mRNA levels of Ucn 1, Ucn 2, or Ucn 3 in both mucosa and S+M layers with a sustained elevation of Ucn 1 mRNA maintained at 24 h postinjection in the S+M layers, whereas Ucn 2 and Ucn 3 were back to control levels. These results provide the first evidence that Ucn ligands are regulated in the stomach under conditions of immune challenge induced by a low dose of LPS (18). Clinical studies indicate that Ucn 1 immunoreactivity was higher in gastric mucosal biopsies from patients with gastritis associated with Heliobacter pylori (9), suggestive of upregulation during conditions of inflammation. Likewise, in experimental animals, these data extend to the stomach the increased Ucn 1 mRNA levels elicited by a low dose of LPS previously found in the rat and mice heart and thymus unlike the spleen where levels were decreased (30, 50). Several possible mechanisms may be involved in the upregulation of gastric Ucn gene expression in response to intraperitoneal LPS in rats that remained to be elucidated. LPS increases corticosterone release under these conditions (30, 58, 61), which has been reported to be involved in the LPS-induced upregulation of Ucn 1 gene expression in the rat thymus (30). Such pathway may be relevant in view of the similar kinetic of peak upregulation occurring at 6 h post-LPS injection observed in both the thymus (30) and the stomach (present study). However, other reports showed that glucocorticoids downregulated Ucn 2 expression in the skin and upregulated its expression in the hypothalamus or brain stem (12, 13), supporting a tissue-specific glucocorticoid regulation of Ucn 2 as reported for Ucn 1 (30) that needs to be delineated specifically in the stomach. Other mechanisms may involve LPS-related release of cytokines and oxidative stress as demonstrated in Ucn 1 and Ucn 2 gene upregulation by LPS in HL-1 cardiomyocytes (28).

By contrast to endogenous CRF2 ligands, CRF2b mRNA level was significantly decreased in the mucosa and S+M as monitored 2, 6, and 9 h after LPS injection, with a recovery to the control level by 24 h only in the mucosa. Likewise, in other viscera, previous studies show that LPS injected intraperitoneally at a similar dose markedly decreased CRF2b mRNA levels in the heart of rats and mice with a parallel time course as observed in our study (23, 31). In a rat model of chemically induced colitis, a similar synchronous decrease of CRF2 mRNA expression with the Ucn 2 peak was found in the colon (8). Mechanisms of modulation of CRF2b expression in the stomach following intraperitoneal LPS need to be defined and may involve several indirect endocrine and immune mediators released by LPS as established in the rodent heart (2, 15, 31, 50). Indeed, the administration of corticosterone, adrenocorticotropin hormone, and several classes of cytokines such as interleukin-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interleukin-6 downregulated CRF2b expression in rodent heart, indicative of a multifactorial regulation of CRF2b in this viscera (2, 15, 31, 50). However, only Ucn 1 decreases CRF2 mRNA levels in the rat heart both in vivo and in vitro (2, 15, 31) in keeping with ligand-induced downregulation of G protein receptors (53). In the present study, the parallel time-related upregulation of Ucns and downregulation of CRF2b gene expression in the GC post-LPS injection may be indicative of potential ligand-receptor reciprocity or interaction. The decrease in CRF2b mRNA levels over time may reflect the suppression of the receptor synthesis, consequently diminishing the number of the receptors contributing to ligand-binding sites, thus restricting subsequent pleiotropic actions of Ucns on the stomach.

Of interest, CRF2a-3 and CRF2a wild type were reciprocally regulated by LPS when monitored at 6 h postinjection in the GC. Like CRF2b, CRF2a was dramatically decreased by LPS in the mucosa and S+M of GC while CRF2a-3 was significantly increased in the mucosa and more prominently in the M+S of GC. Differential downregulation of CRF2b mRNA and upregulation of the new insertion variant CRF2b isoform in the hearts of mice exposed to chronic variable stress was also reported and found to act as a dominant-negative regulator of CRF2b surface expression (56). The finding of a novel CRF2a variant in the stomach, CRF2a-3, that is distinctively expressed and regulated may provide additional targets as either soluble or coreceptor, and yet unrecognized modulation of Ucns action in the stomach.

Functional Role of Ucn/CRF2 Activation in the Gastric-Emptying Alterations Induced by LPS

LPS injected at the same dose upregulating gastric Ucn gene expression delayed gastric emptying by 42% as assessed 2 h post-LPS injection. These data are consistent with previous reports showing a long-lasting reduction of gastric transit of liquid or solid induced by peripheral injection of LPS at similar or lower doses in rats (6, 19, 64). Under these conditions, peripheral injection of the long-lasting CRF2 receptor antagonist astressin2-B (52) further enhanced the inhibitory effect of LPS by 31%. These data are indicative that activation of CRF2 receptors by Ucns plays a role in restraining the inhibitory action of LPS on gastric emptying. This may be mediated by counteracting inflammatory mediators shown to underlie LPS-induced inhibition of gastric emptying, namely the increase in TNF-α-nitric oxide production (29, 51). In support of this assertion, several in vivo and in vitro studies indicate that Ucns exert a CRF2-mediated attenuation of the early phase of LPS-induced inflammatory response by inhibiting TNF-α and interleukin-1 release (1, 59, 60, 66).

In conclusion, the present study delineates for the first time the broad distribution of CRF2b receptor expression and all three Ucn ligands at the mRNA level in the rat GC layers, including myenteric neurons, whereas CRF1 receptor expression was low, emphasizing the prominence of Ucns/CRF2 signaling in the stomach. On the other hand, CRF2a, the major form of CRF2 in human and the one thought to be exclusively expressed in the rodent central nerve system, is nonetheless expressed at a lower level in the rat stomach. Moreover, an even higher level of the truncated CRF2a-3 splice variant was also found in the stomach. The long-lasting upregulation of the Ucns associated with the reciprocal downregulation of CRF2 receptor induced by LPS provides support for the responsiveness of the Ucn/CRF2 signaling system in the stomach to immune challenge. The activation of Ucns/CRF2 signaling plays a role in restraining LPS-induced inhibition of gastric emptying as measured 2 h post-LPS injection, which may be secondary to Ucn reduction of the LPS early phase of the inflammatory response (1, 59, 60, 66). The sustained decreases in both CRF2b and CRF2a mRNA levels and increase in aberrantly spliced CRF2a-3 would result in a reduction in the number of CRF2 receptors, restricting subsequent ligand actions to restore homeostasis.

GRANTS

This research was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) R01 Grant DK-33061, a Veteran Administration (VA) Research Career Scientist Award, a VA Merit Review Award, and Center NIDDK Grant DK-41301 (Animal Core) (Y. Taché).

DISCLOSURE

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. David Scott and George Sachs for providing the LCM facility and helpful advice, Dr. Jean Rivier (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA) for the generous supply of astressin2-B, and Honghui Liang for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Agnello D, Bertini R, Sacco S, Meazza C, Villa P, Ghezzi P. Corticosteroid-independent inhibition of tumor necrosis factor production by the neuropeptide urocortin. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 275: E757–E762, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Asaba K, Makino S, Nishiyama M, Hashimoto K. Regulation of type-2 corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor mRNA in rat heart by glucocorticoids and urocortin. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 36: 493–497, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Asakawa A, Inui A, Ueno N, Makino S, Fujino MA, Kasuga M. Urocortin reduces food intake and gastric emptying in lean and ob/ob obese mice. Gastroenterology 116: 1287–1292, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Basa NR, Wang L, Arteaga JR, Heber D, Livingston EH, Taché Y. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide shifts fasted plasma ghrelin to postprandial levels in rats. Neurosci Lett 343: 25–28, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bittencourt JC, Vaughan J, Arias C, Rissman RA, Vale WW, Sawchenko PE. Urocortin expression in rat brain: evidence against a pervasive relationship of urocortin-containing projections with targets bearing type 2 CRF receptors. J Comp Neurol 415: 285–312, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Calatayud S, Barrachina MD, Garcia-Zaragoza E, Quintana E, Esplugues JV. Endotoxin inhibits gastric emptying in rats via a capsaicin-sensitive afferent pathway. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 363: 276–280, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang J, Adams MR, Clifton MS, Liao M, Brooks JH, Hasdemir B, Bhargava A. Urocortin 1 modulates immunosignaling in a rat model of colitis via corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 2. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 300: G884–G894, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chang J, Hoy JJ, Idumalla PS, Clifton MS, Pecoraro NC, Bhargava A. Urocortin 2 expression in the rat gastrointestinal tract under basal conditions and in chemical colitis. Peptides 28: 1453–1460, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chatzaki E, Charalampopoulos I, Leontidis C, Mouzas IA, Tzardi M, Tsatsanis C, Margioris AN, Gravanis A. Urocortin in human gastric mucosa: relationship to inflammatory activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88: 478–483, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chatzaki E, Lambropoulou M, Constantinidis TC, Papadopoulos N, Taché Y, Minopoulos G, Grigoriadis DE. Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) receptor type 2 in the human stomach: protective biological role by inhibition of apoptosis. J Cell Physiol 209: 905–911, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chatzaki E, Murphy BJ, Wang L, Million M, Ohning GV, Crowe PD, Petroski R, Taché Y, Grigoriadis DE. Differential profile of CRF receptor distribution in the rat stomach and duodenum assessed by newly developed CRF receptor antibodies. J Neurochem 88: 1–11, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen A, Blount A, Vaughan J, Brar B, Vale W. Urocortin II gene is highly expressed in mouse skin and skeletal muscle tissues: localization, basal expression in corticotropin-releasing factor receptor (CRFR) 1- and CRFR2-null mice, and regulation by glucocorticoids. Endocrinology 145: 2445–2457, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen A, Vaughan J, Vale WW. Glucocorticoids regulate the expression of the mouse urocortin II gene: a putative connection between the corticotropin-releasing factor receptor pathways. Mol Endocrinol 17: 1622–1639, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen AM, Perrin MH, Digruccio MR, Vaughan JM, Brar BK, Arias CM, Lewis KA, Rivier JE, Sawchenko PE, Vale WW. A soluble mouse brain splice variant of type 2α corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) receptor binds ligands and modulates their activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 2620–2625, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Coste SC, Heldwein KA, Stevens SL, Tobar-Dupres E, Stenzel-Poore MP. IL-1alpha and TNFalpha down-regulate CRH receptor-2 mRNA expression in the mouse heart. Endocrinology 142: 3537–3545, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Czimmer J, Million M, Taché Y. Urocortin 2 acts centrally to delay gastric emptying through sympathetic pathways while CRF and urocortin 1 inhibitory actions are vagal dependent in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 290: G511–G518, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fekete EM, Zorrilla EP. Physiology, pharmacology, and therapeutic relevance of urocortins in mammals: ancient CRF paralogs. Front Neuroendocrinol 28: 1–27, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Givalois L, Dornand J, Mekaouche M, Solier MD, Bristow AF, Ixart G, Siaud P, Assenmacher I, Barbanel G. Temporal cascade of plasma level surges in ACTH, corticosterone, and cytokines in endotoxin-challenged rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 267: R164–R170, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goebel M, Stengel A, Wang L, Reeve J, Jr, Taché Y. Lipopolysaccharide increases plasma levels of corticotropin-releasing hormone in rats. Neuroendocrinology 93: 165–173, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gourcerol G, Wang L, Wang YH, Million M, Taché Y. Urocortins and cholecystokinin-8 act synergistically to increase satiation in lean but not obese mice: involvement of corticotropin-releasing factor receptor-2 pathway. Endocrinology 148: 6115–6123, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Habib KE, Weld KP, Rice KC, Pushkas J, Champoux M, Listwak S, Webster EL, Atkinson AJ, Schulkin J, Contoreggi C, Chrousos GP, McCann SM, Suomi SJ, Higley JD, Gold PW. Oral administration of a corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor antagonist significantly attenuates behavioral, neuroendocrine, and autonomic responses to stress in primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 6079–6084, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harada S, Imaki T, Naruse M, Chikada N, Nakajima K, Demura H. Urocortin mRNA is expressed in the enteric nervous system of the rat. Neurosci Lett 267: 125–128, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hashimoto K, Nishiyama M, Tanaka Y, Noguchi T, Asaba K, Hossein PN, Nishioka T, Makino S. Urocortins and corticotropin releasing factor type 2 receptors in the hypothalamus and the cardiovascular system. Peptides 25: 1711–1721, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hauger RL, Grigoriadis DE, Dallman MF, Plotsky PM, Vale WW, Dautzenberg FM. International Union of Pharmacology. XXXVI. Current status of the nomenclature for receptors for corticotropin-releasing factor and their ligands. Pharmacol Rev 55: 21–26, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Heinrichs SC, Koob GF. Corticotropin-releasing factor in brain: a role in activation, arousal, and affect regulation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 311: 427–440, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Holst MC, Powley TL. Cuprolinic blue (quinolinic phthalocyanine) counterstaining of enteric neurons for peroxidase immunocytochemistry. J Neurosci Methods 62: 121–127, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hsu SY, Hsueh AJ. Human stresscopin and stresscopin-related peptide are selective ligands for the type 2 corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor. Nat Med 7: 605–611, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ikeda K, Tojo K, Inada Y, Takada Y, Sakamoto M, Lam M, Claycomb WC, Tajima N. Regulation of urocortin I and its related peptide urocortin II by inflammatory and oxidative stresses in HL-1 cardiomyocytes. J Mol Endocrinol 42: 479–489, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Inada T, Hamano N, Yamada M, Shirane A, Shingu K. Inducible nitric oxide synthase and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in delayed gastric emptying and gastrointestinal transit induced by lipopolysaccharide in mice. Braz J Med Biol Res 39: 1425–1434, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kageyama K, Bradbury MJ, Zhao L, Blount AL, Vale WW. Urocortin messenger ribonucleic acid: tissue distribution in the rat and regulation in thymus by lipopolysaccharide and glucocorticoids. Endocrinology 140: 5651–5658, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kageyama K, Gaudriault GE, Bradbury MJ, Vale WW. Regulation of corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 2 beta messenger ribonucleic acid in the rat cardiovascular system by urocortin, glucocorticoids, and cytokines. Endocrinology 141: 2285–2293, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kageyama K, Li C, Vale WW. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 2 messenger ribonucleic acid in rat pituitary: localization and regulation by immune challenge, restraint stress, and glucocorticoids. Endocrinology 144: 1524–1532, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kihara N, Fujimura M, Yamamoto I, Itoh E, Inui A, Fujimiya M. Effects of central and peripheral urocortin on fed and fasted gastroduodenal motor activity in conscious rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 280: G406–G419, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kishimoto T, Pearse RV, Lin CR, Rosenfeld MG. A sauvagine/corticotropin-releasing factor receptor expressed in heart and skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 1108–1112, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kozicz T, Arimura A. Distribution of urocortin in the rat's gastrointestinal tract and its colocalization with tyrosine hydroxylase. Peptides 23: 515–521, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Krammer HJ, Karahan ST, Rumpel E, Klinger M, Kuhnel W. Immunohistochemical visualization of the enteric nervous system using antibodies against protein gene product (PGP) 9.5. Anat Anz 175: 321–325, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Langhans W. Bacterial products and the control of ingestive behavior: clinical implications. Nutrition 12: 303–315, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Langhans W. Anorexia of infection: current prospects. Nutrition 16: 996–1005, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li C, Chen P, Vaughan J, Blount A, Chen A, Jamieson PM, Rivier J, Smith MS, Vale W. Urocortin III is expressed in pancreatic beta-cells and stimulates insulin and glucagon secretion. Endocrinology 144: 3216–3224, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li C, Chen P, Vaughan J, Lee KF, Vale W. Urocortin 3 regulates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and energy homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 4206–4211, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lovenberg TW, Chalmers DT, Liu C, De Souza EB. CRF2α and CRF2β receptor mRNAs are differentially distributed between the rat central nervous system and peripheral tissues. Endocrinology 136: 4139–4142, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Martinez V, Rivier J, Taché Y. Peripheral injection of a new corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) antagonist, astressin, blocks peripheral CRF-and abdominal surgery-induced delayed gastric emptying in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 290: 629–634, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Martinez V, Wang L, Million M, Rivier J, Taché Y. Urocortins and the regulation of gastrointestinal motor function and visceral pain. Peptides 25: 1733–1744, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Million M, Maillot C, Saunders PR, Rivier J, Vale W, Taché Y. Human urocortin II, a new CRF-related peptide, displays selective CRF2-mediated action on gastric transit in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 282: G34–G40, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nozu T, Martinez V, Rivier J, Taché Y. Peripheral urocortin delays gastric emptying: role of CRF receptor 2. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 276: G867–G875, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Oki Y, Iwabuchi M, Masuzawa M, Watanabe F, Ozawa M, Iino K, Tominaga T, Yoshimi T. Distribution and concentration of urocortin, and effect of adrenalectomy on its content in rat hypothalamus. Life Sci 62: 807–812, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Perrin M, Donaldson C, Chen R, Blount A, Berggren T, Bilezikjian L, Sawchenko P, Vale W. Identification of a second corticotropin-releasing factor receptor gene and characterization of a cDNA expressed in heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 2969–2973, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Perrin MH, Vale WW. Corticotropin releasing factor receptors and their ligand family. Ann NY Acad Sci 885: 312–328, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Porcher C, Peinnequin A, Pellissier S, Meregnani J, Sinniger V, Canini F, Bonaz B. Endogenous expression and in vitro study of CRF-related peptides and CRF receptors in the rat gastric antrum. Peptides 27: 1464–1475, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pournajafi NH, Tanaka Y, Dorobantu M, Hashimoto K. Modulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor type 2 mRNA expression by CRH deficiency or stress in the mouse heart. Regul Pept 115: 131–138, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Quintana E, Hernandez C, Alvarez-Barrientos A, Esplugues JV, Barrachina MD. Synthesis of nitric oxide in postganglionic myenteric neurons during endotoxemia: implications for gastric motor function in rats. FASEB J 18: 531–533, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rivier J, Gulyas J, Kirby D, Low W, Perrin MH, Kunitake K, DiGruccio M, Vaughan J, Reubi JC, Waser B, Koerber SC, Martinez V, Wang L, Taché Y, Vale W. Potent and long-acting corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) receptor 2 selective peptide competitive antagonists. J Med Chem 45: 4737–4747, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Smit MJ, Roovers E, Timmerman H, van d V, Alewijnse AE, Leurs R. Two distinct pathways for histamine H2 receptor down-regulation. H2 Leu124 → Ala receptor mutant provides evidence for a cAMP-independent action of H2 agonists. J Biol Chem 271: 7574–7582, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Stengel A, Taché Y. Corticotropin-releasing factor signaling and visceral response to stress. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 235: 1168–1178, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Suto G, Kiraly A, Plourde V, Taché Y. Intravenous interleukin-1-beta-induced inhibition of gastric emptying: involvement of central corticotropin-releasing factor and prostaglandin pathways in rats. Digestion 57: 135–140, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sztainberg Y, Kuperman Y, Issler O, Gil S, Vaughan J, Rivier J, Vale W, Chen A. A novel corticotropin-releasing factor receptor splice variant exhibits dominant negative activity: a putative link to stress-induced heart disease. FASEB J 23: 2186–2196, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Takahashi K, Totsune K, Murakami O, Shibahara S. Urocortins as cardiovascular peptides. Peptides 25: 1723–1731, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Takemura T, Makino S, Takao T, Asaba K, Suemaru S, Hashimoto K. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical responses to single vs. repeated endotoxin lipopolysaccharide administration in the rat. Brain Res 767: 181–191, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Torricelli M, Voltolini C, Bloise E, Biliotti G, Giovannelli A, De Bonis M, Imperatore A, Petraglia F. Urocortin increases IL-4 and IL-10 secretion and reverses LPS-induced TNF-alpha release from human trophoblast primary cells. Am J Reprod Immunol 62: 224–231, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tsatsanis C, Androulidaki A, Dermitzaki E, Gravanis A, Margioris AN. Corticotropin releasing factor receptor 1 (CRF1) and CRF2 agonists exert an anti-inflammatory effect during the early phase of inflammation suppressing LPS-induced TNF-alpha release from macrophages via induction of COX-2 and PGE2. J Cell Physiol 210: 774–783, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Turnbull AV, Lee S, Rivier C. Mechanisms of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis stimulation by immune signals in the adult rat. Ann NY Acad Sci 840: 434–443, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Turnbull AV, Rivier C. Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and endocrine response to stress: CRF receptors, binding protein, and related peptides. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 215: 1–10, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Van Pett K, Viau V, Bittencourt JC, Chan RK, Li HY, Arias C, Prins GS, Perrin M, Vale W, Sawchenko PE. Distribution of mRNAs encoding CRF receptors in brain and pituitary of rat and mouse. J Comp Neurol 428: 191–212, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wang L, Basa NR, Shaikh A, Luckey A, Heber D, St Pierre DH, Taché Y. LPS inhibits fasted plasma ghrelin levels in rats: role of IL-1 and PGs and functional implications. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 291: G611–G620, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wang L, Stengel A, Goebel M, Martinez V, Gourcerol G, Rivier J, Taché Y. Peripheral activation of corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 2 inhibits food intake and alters meal structures in mice. Peptides 32: 51–59, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wang MJ, Lin SZ, Kuo JS, Huang HY, Tzeng SF, Liao CH, Chen DC, Chen WF. Urocortin modulates inflammatory response and neurotoxicity induced by microglial activation. J Immunol 179: 6204–6214, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wu SV, Yuan PQ, Wang L, Peng YL, Chen CY, Taché Y. Identification and characterization of multiple corticotropin-releasing factor type 2 receptor isoforms in the rat esophagus. Endocrinology 148: 1675–1687, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yamauchi N, Otagiri A, Nemoto T, Sekino A, Oono H, Kato I, Yanaihara C, Shibasaki T. Distribution of urocortin 2 in various tissues of the rat. J Neuroendocrinol 17: 656–663, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Yin Y, Dong L, Yin D. Peripheral and central administration of exogenous urocortin 1 disrupts the fasted motility pattern of the small intestine in rats via the corticotrophin releasing factor receptor 2 and a cholinergic mechanism. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 23: e79–e87, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zmijewski MA, Slominski AT. Emerging role of alternative splicing of CRF1 receptor in CRF signaling. Acta Biochim Pol 57: 1–13, 2010 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]