Abstract

Although gastric acid aspiration causes rapid lung inflammation and acute lung injury, the initiating mechanisms are not known. To determine alveolar epithelial responses to acid, we viewed live alveoli of the isolated lung by fluorescence microscopy, then we microinjected the alveoli with HCl at pH of 1.5. The microinjection caused an immediate but transient formation of molecule-scale pores in the apical alveolar membrane, resulting in loss of cytosolic dye. However, the membrane rapidly resealed. There was no cell damage and no further dye loss despite continuous HCl injection. Concomitantly, reactive oxygen species (ROS) increased in the adjacent perialveolar microvascular endothelium in a Ca2+-dependent manner. By contrast, ROS did not increase in wild-type mice in which we gave intra-alveolar injections of polyethylene glycol (PEG)-catalase, in mice overexpressing alveolar catalase, or in mice lacking functional NADPH oxidase (Nox2). Together, our findings indicate the presence of an unusual proinflammatory mechanism in which alveolar contact with acid caused membrane pore formation. The effect, although transient, was nevertheless sufficient to induce Ca2+ entry and Nox2-dependent H2O2 release from the alveolar epithelium. These responses identify alveolar H2O2 release as the signaling mechanism responsible for lung inflammation induced by acid and suggest that intra-alveolar PEG-catalase might be therapeutic in acid-induced lung injury.

Keywords: calcium, hydrogen peroxide, nitric oxide synthase 2, nitric oxide, reactive oxygen species, catalase, flash photolysis, resealing, clodronate

the gastric and the pulmonary epithelial surfaces are potentially exposed to highly concentrated HCl. The gastric epithelium secretes the acid at pH 1–2; the pulmonary epithelium encounters the acid following aspiration of gastric contents. Although a 200-μm-thick mucus layer protects the gastric epithelium from acid injury (4), the much thinner layer of surfactant (6) is likely to provide relatively little protection to alveoli. Large aspirations cause severe lung inflammation, leading to acute lung injury (ALI) that associates with high mortality and morbidity (21). Mild aspirations prime the lung for secondary pneumonitis (30, 34). No specific treatment is available for acid-induced ALI.

An unsolved problem in the understanding of acid-induced ALI relates to the question of how the injury initiates following the first contact of acid with the alveolar membrane. Particularly lacking is the absence of studies defining the immediate alveolar response to the acid contact. Although animal studies confirm that airway instillation of highly concentrated acid (pH <2) causes ALI, these studies have largely focused on lung responses occurring well after the injury has already taken place (10, 15, 36, 37). Importantly, no clear understanding exists on how alveolar contact with HCl initiates a full-blown innate immune response that tends to be similar to the acute immune responses initiated by receptor-mediated mechanisms such as by bacterial endotoxin (7, 33).

Here we addressed the immediate responses of alveoli following contact with concentrated acid, by means of live optical imaging (18). We assessed damage to the alveolar membrane in terms of dye leakage from the alveolar epithelial cytosol. Our findings provide novel evidence that the first-contact effect of concentrated HCl is to induce membrane pores and Ca2+ entry in the alveolar epithelium. We show for the first time that, although membrane repair mechanisms sealed the pores, protecting the alveolar epithelium from disruptive effects of acid, the pores initiated proinflammatory signaling in adjoining blood vessels.

METHODS

Fluorescent dyes and reagents.

2′,7′-Bis(2-carboxyethyl)-5 (and 6)-carboxyfluorescein-AM (BCECF-AM), calcein red-orange AM, fura 2-AM, fluo 4-AM, o-nitrophenyl EGTA-AM (NP-EGTA-AM), 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCF), and N-(3-triethylammoniumpropyl)-4-[4-(dibutyl-amino)stytyl]pyridinium dibromide FM1-43 were from Molecular Probes. Anti-mouse NADPH oxidase (Nox 2) antibody (Ab) was from BD Bioscience, and anti-mouse F4/80 was from eBioscience. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran of molecular mass 4 kDa (FD4) and 250 kDa (FD250), thrombin, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME), and polyethylene glycol (PEG)-catalase were from Sigma-Aldrich. Saponin was from Calbiochem-Novabiochem. Solutions were prepared in HEPES buffer (in mM: 150 Na+, 5 K+, 1 Ca2+, 1 Mg2+, 20 HEPES, and 10 glucose).

For vascular perfusates, 4% dextran-70 and 1% FBS were added. Inclusion of 4% dextran (70 kDa) in HEPES buffer maintains colloid osmotic pressure of 20 cmH2O (26). The pH was set at 7.4. For acid microinfusion, buffer was titrated with HCl to indicated pH values. To establish Ca2+-free conditions, we used Ca2+-free HEPES-buffered Ringer solution containing 5 mM EDTA.

Lung preparation.

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Center and Columbia University Medical Center. Using our reported methods (19, 20), lungs were isolated from Sprague-Dawley rats (Taconic Farms) and Swiss Webster wild-type mice (Jackson Laboratory). The Nox2−/− mice as well as their age-matched controls were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). For intratracheal acid instillation, 2 ml/kg HCl were injected through an airway cannula followed by a brief inflation.

Real-time lung imaging.

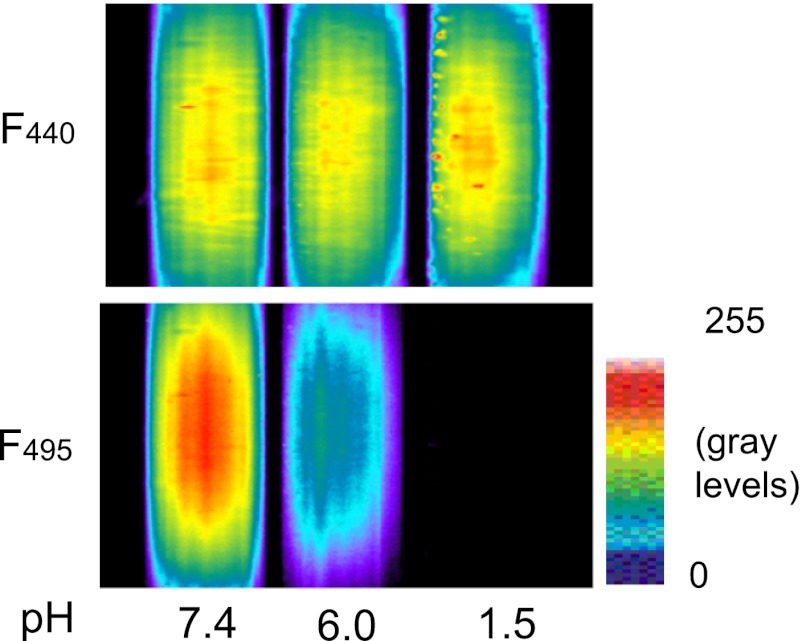

Lungs were positioned under either an Olympus AX 70 microscope for wide-field epifluorescence imaging, a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta Confocal microscope, or a Nikon E 600/Bio-Rad 2100 MP system for two-photon imaging. To label the alveolar epithelium, alveoli were micropunctured to load fluorophores (20). For intramicrovascular infusion, fluorophores were either delivered through a vascular microcatheter (19) or added to the perfusate. Image acquisition was controlled by MCID (Imaging Research), MetaFluor (Molecular Devices), Zeiss LSM, and Bio-Rad Lasersharp software. For alveolar micropuncture and microinfusion, we used our previously reported methods (3, 13). To view the alveolar epithelium, we loaded the alveolar cytosol with the fluorescent dye BCECF (5 μM) by means of a 20-min intra-alveolar microinfusion. Cytosolic fluorescence was determined as the pH-independent BCECF fluorescence excited at 440 nm (27) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of pH on 2′,7′-bis(2-carboxyethyl)-5 (and 6)-carboxyfluorescein (BCECF) fluorescence. Images show pseudocolored fluorescence of BCECF excited at 440 (F440, top) and 495 (F495, bottom) nm. BCECF (3 μM, each) was dissolved in buffer of indicated pH and held in glass pipettes. Note, F440 is pH-independent.

Ca2+ imaging.

Ca2+ imaging and analysis methods have been reported (25). Fura 2-AM (10 μM) was given for 30 min by intramicrovascular infusion. Fura 2 was excited at 340 and 380 nm, and cytosolic Ca2+ was determined from the computer-generated 340:380 ratio. In uncaging experiments, fluo 4 (10 μm) was loaded for 40 min, and the fluorescence was excited at 495 nm.

Reactive oxygen species imaging.

DCF (5 μM) was added to the lung perfusate at least 30 min before the experiment and maintained during imaging to account for DCF leaking from microvascular endothelial cells (25). Excitation was at 495 nm every 20–60 s to prevent photoactivation of DCF (25). PEG-catalase (100 U/ml) was given by a 20-min intra-alveolar microinfusion immediately before the experiment or added to the lung perfusion 30 min before the experiment and then maintained during the experiment.

Dextran imaging.

FITC-dextran (3 mg/ml) with a molecular size of 4 (FD4) or 250 (FD250) kDa was given by alveolar micropuncture as a 5-min coinjection with acid.

Photoexcited Ca2+ uncaging.

We photolytically uncaged NP-EGTA in a circle of ∼70 μm diameter as reported (13) in NP-EGTA-loaded (100 μM) alveoli. Uncaging occurred in 20–30 s.

In situ immunofluorescence.

For Nox2 immunostaining, we superfused isolated lungs with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, gave 5 min intra-alveolar microinfusions of saponin (0.1%), and then microinfused anti-mouse Nox2 Ab (BD Bioscience) and Alexa 488 conjugated IgG (1:200, each) each followed by buffer wash. For staining of alveolar macrophages, anti-mouse F4/80 Ab was microinfused in unfixed alveoli for 30 min, followed by buffer wash.

Lung transfection.

The cytosolic catalase construct was provided by Dr. J. A. Melendez (Albany Medical College) (5) and subcloned into the pBI-CMV bidirectional vector for DsRed (Clontech). We complexed plasmid (2.5 μg/μl) with unilamellar liposomes (20 μg/μl, 100 nm pore size, DOTAP; Avanti Lipids) in sterile PBS to a final concentration of 0.5 μg oligonucleotide/μl and instilled 50 μl/animal in airways of anesthetized mice. We excised the lungs 48 h later for imaging.

EVLW and lung blood content.

Mice were anesthetized in an isoflorane chamber, followed by an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (80–100 mg/kg) and xylazine (5–10 mg/kg). The trachea was exposed through a midline neck incision then cannulated with a PE-90 tube, and 2 ml/kg acid (pH 1.5) or buffer (pH 7.4) was instilled. Animals were maintained anesthetized and allowed to breathe spontaneously for 2 h. We then determined the blood-free EVLW content by the method of Selinger and colleagues (29).

Statistics.

All data are represented as means ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaStat (Systat Software). Comparisons between the groups were tested using ANOVA on ranks by Dunn's method. Repeated measurements were tested using the Mann-Whitney Rank Sum Test. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Membrane resealing after acid injury.

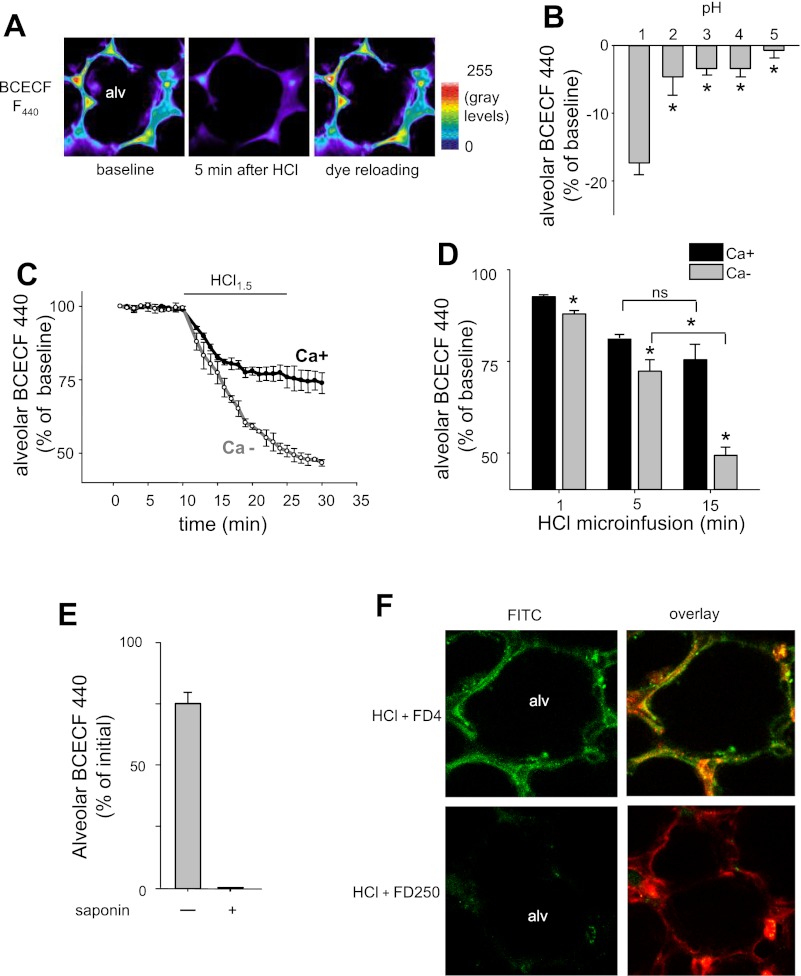

A 5-min intra-alveolar microinfusion of HCl at pH 1.5 (hereafter referred to as “alveolar HCl infusion”) decreased alveolar fluorescence of BCECF within 5 min (Fig. 2A). HCl at pH >2 caused no major effect (Fig. 2B). Twenty minutes after the alveolar HCl infusion, microinjection of BCECF reinstated alveolar fluorescence to baseline levels and remained locked in the cytosol (Fig. 2A) for a further 20 min (data not shown). These findings indicate that, although the HCl infusion caused immediate membrane injury, resulting in loss of the intracellular dye, the membrane repaired quickly and spontaneously such that the epithelium could be reloaded with the cytosolic dye that remained locked in the cytosol.

Fig. 2.

Effect of HCl on alveolar epithelial cells. Alv, alveolar lumen. A: images in pseudocolor show pH-independent BCECF F440 in the alveolar epithelium. Image in middle was acquired 5 min after alveolar HCl infusion of pH 1.5. Image on right was obtained by reloading the alveolus with BCECF 30 min after the HCl infusion. Replicated 4 times. B: response of alveolar BCECF F440 to 5-min microinfusions of HCl at indicated pH. Means ± SE; n = 3 lungs; *P < 0.05. C and D: group data show alveolar epithelial BCECF F440 in response to 15 min alveolar HCl of pH 1.5 in 1 mM Ca2+-containing (Ca+) or Ca2+-free (Ca−) buffer. Means ± SE; n = 3 lungs; *P < 0.05 vs. Ca+. Brackets compare 5 vs. 15 min for Ca2+-free or -containing microinfusions, respectively. ns, Not significant. E: residual BCECF F440 in the cytosol of alveolar epithelial cells after a 20-min alveolar HCl infusion at pH 1.5. Saponin (0.1%) was given at the end of the HCl infusion. F: two-photon images of single alveoli (alv) taken 5 min after alveolar HCl infusion at pH 1.5 containing fluorescent dextran of molecular mass 4 kDa (FD4) and 250 kDa (FD250). Images on left show dextran fluorescence (green), and images on right show overlay with alveolar epithelial cytosolic calcein red-orange fluorescence (red), indicating cytosolic uptake of FD4. Replicated 3 times.

To determine the effect of sustained acid contact with the alveolus, we imaged alveoli during a continuous 20-min microinfusion of HCl. This prolonged microinfusion decreased cytosolic BCECF fluorescence by 25% of initial within 5 min (Fig. 2, C and D). However, subsequently, no further fluorescence decrease occurred even though we maintained the HCl infusion (Fig. 2, C and D). The residual cytosolic fluorescence at the end of the HCl infusion was due to retained dye and not autofluorescence, since membrane permeabilization by intra-alveolar injection of saponin released the residual dye and abolished cytosolic fluorescence (Fig. 2E). These findings suggest that, although membrane injury occurred after the first contact with acid, the ensuing membrane repair was sufficiently robust that the continued presence of HCl did not induce further injury. By contrast, when we gave a 20-min alveolar HCl infusion in Ca2+-free buffer, the dye loss occurred progressively during the HCl infusion (Fig. 2, C and D). At the end of the infusion, the dye loss was two times greater for the Ca2+-free than the Ca2+-containing buffer solution. These findings indicate that Ca2+-free conditions inhibited the repair response to acid-induced membrane injury.

Membrane pore formation.

To determine the size of the membrane leak, we gave 5-min alveolar infusions of HCl together with the fluorescent dextrans, FD4 or FD250. FD4, but not FD250, increased epithelial fluorescence, indicating that FD4 entered the epithelial cytosol through HCl-induced membrane pores and was then locked in the cytosol after the membrane resealed (Fig. 2F). FD4 in pH-neutral buffer did not enter the alveolar epithelium and could be completely washed out from the alveolar space (data not shown).

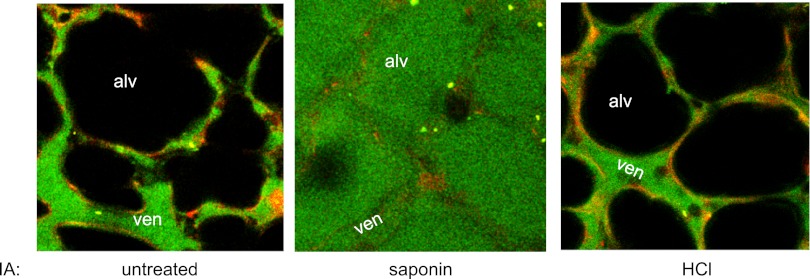

Next, we determined whether the membrane pore formation due to the alveolar HCl infusion induced alveolar edema, as detected by the alveolar appearance of FD4 that we added to the lung perfusion. In untreated alveoli, FD4 fluorescence did not increase in the alveolar lumen after a 20-min perfusion with the fluorescent tracer (Fig. 3), indicating that FD4 was incapable of crossing from microvessels to the alveoli under noninjured conditions. Alveolar injection of the detergent saponin increased the fluorescence within 10 min (Fig. 3), indicating that when we disrupted the alveolar membrane with a strong detergent, FD4 fluorescence increased in the alveolus resulting in alveolar edema. By contrast, a 20-min alveolar HCl infusion failed to increase alveolar fluorescence of FD4 (Fig. 3), indicating that the membrane pore formation caused by alveolar HCl was itself not sufficient to induce alveolar edema. The saponin and HCl infusions were given by an identical protocol and reached the same numbers of alveoli; hence, the difference in the edema response was not due to differences in the alveolar surface areas affected by the infusions. These findings suggested that the lung's inflammatory response to alveolar acid resulted from secondary effects of the transient alveolar injury caused by acid contact with the epithelium.

Fig. 3.

Detection of alveolar edema. Two-photon images of single alveoli (alv) and perialveolar venules (ven). IA, intra-alveolar infusion of saponin (0.1%) or HCl at pH 1.5. Red fluorescence indicates calcein red in the microvascular endothelial cytosol. Green fluorescence is of 4 kDa fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran circulating in the perfusion buffer. Replicated 4 times.

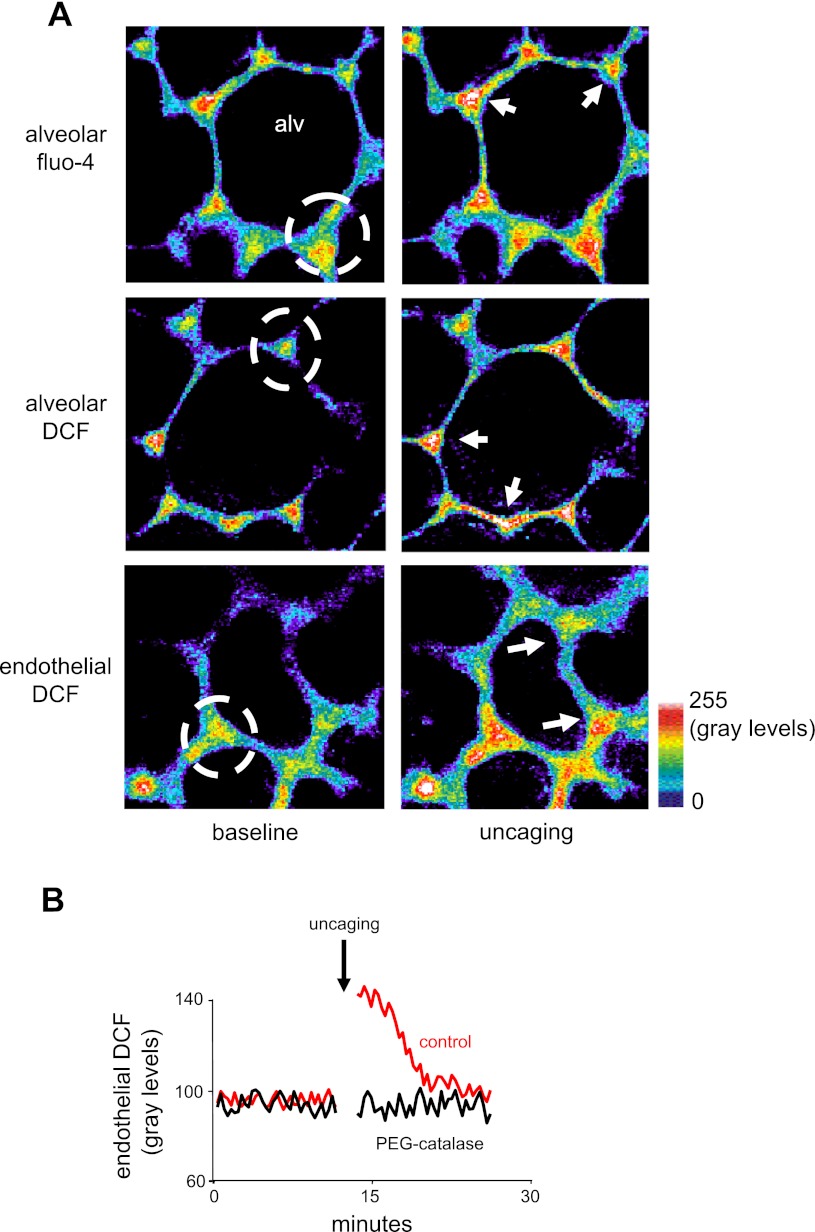

Alveolo-capillary signaling.

To determine the role of alveolar epithelial Ca2+ as a possible factor in these effects, we loaded the alveolar epithelium with the Ca2+ cage, NP-EGTA. In addition, in separate experiments, we loaded the alveolar epithelium or the microvascular endothelium with Ca2+- and reactive oxygen species (ROS)-sensitive dyes (18). Next, we uncaged Ca2+ in the alveolar epithelium by targeting flash photolysis to specific alveolar regions (13).

Uncaging in the alveolar epithelium increased ROS in both the epithelium and the adjoining microvascular endothelium (Fig. 4, A and B). Uncaging in the microvascular endothelium, not loaded with the Ca2+-cage, did not increase ROS (data not shown), ruling out the possibility that the uncaging-induced microvascular ROS increase was a nonspecific effect of dye leakage across the alveolar membrane. PEG-catalase scavenges extracellular H2O2 (31). Microvascular infusion of PEG-catalase completely inhibited the uncaging-induced microvascular ROS increase (Fig. 4B). This finding indicates that the uncaging caused alveolar H2O2 release, which diffused to the adjoining microvessels.

Fig. 4.

Effect of alveolar Ca2+ on endothelial reactive oxygen species (ROS). Alv, alveolar lumen. A: images of alveoli (top and middle) and perialveolar microvessels (bottom) loaded with the indicated dyes. The alveoli were also coloaded with the Ca2+ cage o-nitrophenyl EGTA (NP-EGTA). Images show fluorescence gray levels in pseudocolor before (baseline) and after (uncaging) localized photo excitation. Dashed circle indicates area of uncaging. Fluorescence increased at sites that were directly photo excited as well as at sites (arrows) outside the region of photo excitation. Replicated 3 times each. B: traces show time course of endothelial 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCF) responses to Ca2+ uncaging (arrow) in adjoining alveolar epithelial cells. Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-catalase was perfused in the microvasculature. Replicated 5 times each.

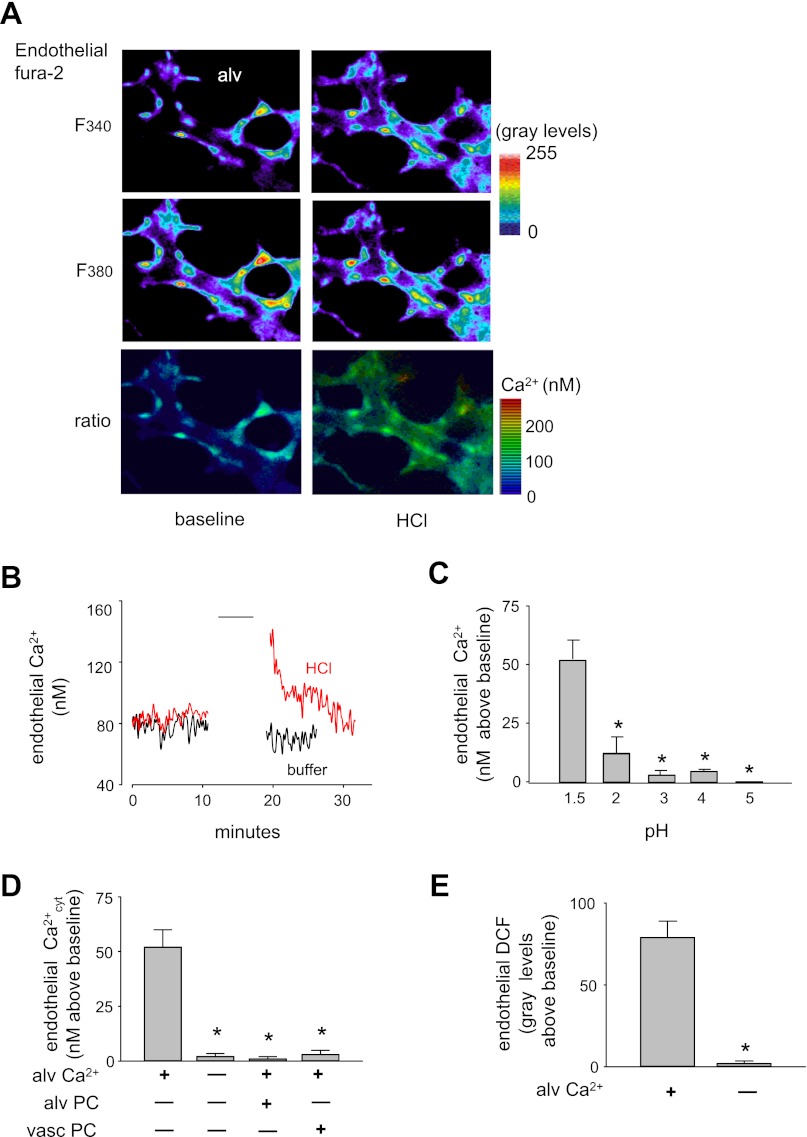

In microvessels loaded with the Ca2+ dye fura 2, an alveolar HCl infusion caused rapid endothelial Ca2+ increases (Fig. 5, A and B). Similar to the dye leak response, HCl at pH >2 caused markedly diminished Ca2+ responses (Fig. 5C). Alveolar HCl infusion under Ca2+-free conditions failed to induce the Ca2+ and ROS responses in the capillary endothelium (Fig. 5, D and E). Infusion of PEG-catalase in alveoli or in microvessels each blocked the microvascular Ca2+ response to alveolar HCl (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Effect of alveolar HCl infusions on endothelial Ca2+ responses in perialveolar microvessels. Alveolar HCl infusions were given at pH 1.5 except for C. A: images show pseudocolored fluorescence of fura 2 in endothelial cells of a perialveolar venule excited at 340 and 380 nm (F340, F380). Pseudocolors of the F340/F380 ratio indicate endothelial Ca2+ concentration. Replicated 4 times. B: tracings show endothelial Ca2+ response time course to acid or buffer given for 5 min (line). Replicated 4 times. C: effect of 5 min alveolar HCl infusions at different pH on endothelial Ca2+ response. Means ± SE, n = 3 lungs, *P < 0.05 against first bar. D and E: effects of Ca2+-free or Ca2+-containing alveolar HCl infusions on microvascular Ca2+ (D) or ROS (E) response. PEG-catalase (PC) was given by 20-min alveolar (alv) infusion or microvascular (vasc) perfusion. Means ± SE; n = 4 lungs each bar; *P < 0.05 against first bar.

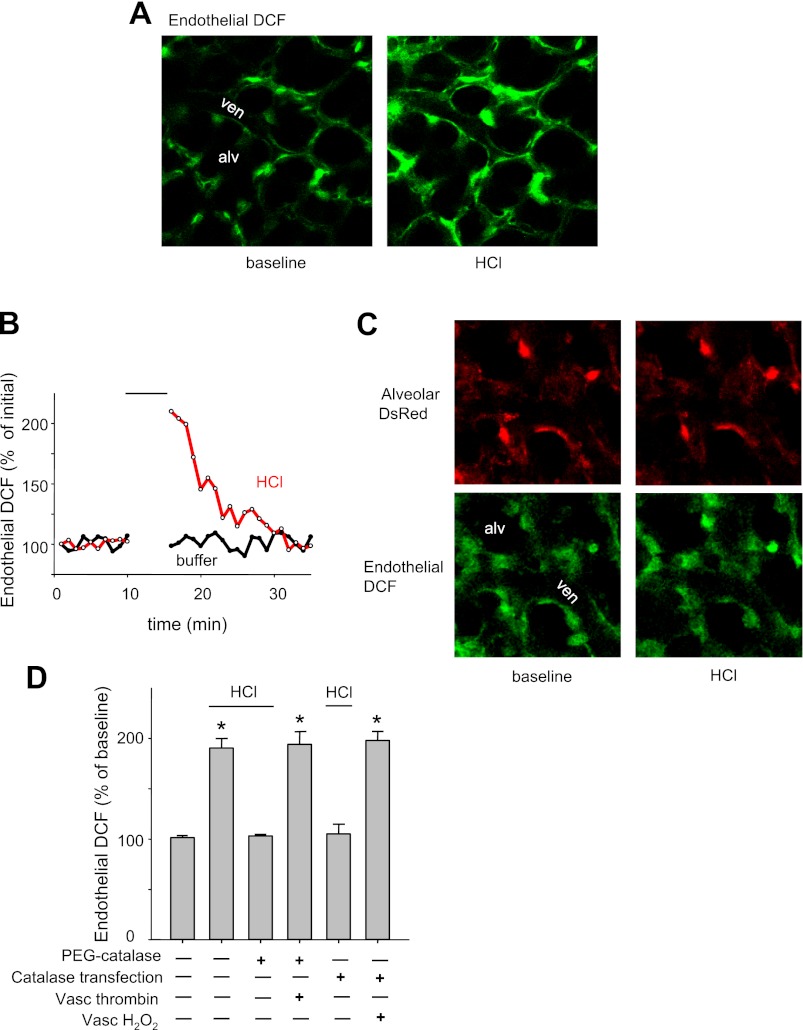

Consistent with these findings, alveolar HCl infusion caused an immediate but transient increase in microvascular ROS (Fig. 6, A and B). To identify the ROS species, we overexpressed alveolar catalase to scavenge H2O2. Lung transfection with a DsRed-expressing catalase construct revealed extensive DsRed fluorescence in the alveolar epithelium (Fig. 6C), confirming successful expression of the construct. Catalase overexpression in the alveolar epithelium did not affect the microvascular increase of DCF fluorescence following vascular H2O2 infusion (Fig. 6D), further affirming that the overexpression was restricted to the alveolus. In untransfected lungs, the absence of DsRed fluorescence was evident as black images (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Effect of intra-alveolar HCl on microvascular ROS response. ven, Venular lumen; alveolar HCl infusions were given at pH 1.5. A: images show endothelial DCF fluorescence of a microvascular network under baseline conditions and immediately after alveolar HCl infusion. Replicated 3 times. B: tracings show endothelial DCF response to 5-min alveolar infusions of indicated agents. Replicated 3 times. C: images of alveoli transfected with catalase construct encoding DsRed (top). Endothelial DCF response to alveolar HCl infusion is blocked (bottom). Replicated 3 times. D: endothelial DCF fluorescence in untreated mice and mice transfected with cytosolic catalase by intratracheal instillation. PEG-catalase was alveolar microinfused for 20 min, immediately before HCl. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 100 μM) and thrombin (10 U/ml) were added to the perfusate. First bar: 5 min intra-alveolar buffer-microinfusion. Lines indicate where alveolar HCl was infused. Means ± SE; n = 3 lungs; P < 0.05 against buffer infusion.

In catalase-overexpressing alveoli, alveolar HCl infusion did not increase microvascular DCF fluorescence (Fig. 6, C and D). Furthermore, this negative response to alveolar HCl was also replicated in alveoli in which we preinfused PEG-catalase (Fig. 6D). As positive control for the PEG-catalase experiments, we showed that intravascular thrombin was capable of increasing microvascular ROS (Fig. 6D), ruling out the possibility that the inhibition due to PEG-catalase was because of nonspecific factors. Taken together, these findings indicate that the increase of microvascular DCF fluorescence was due to alveolar H2O2 release.

Macrophage role.

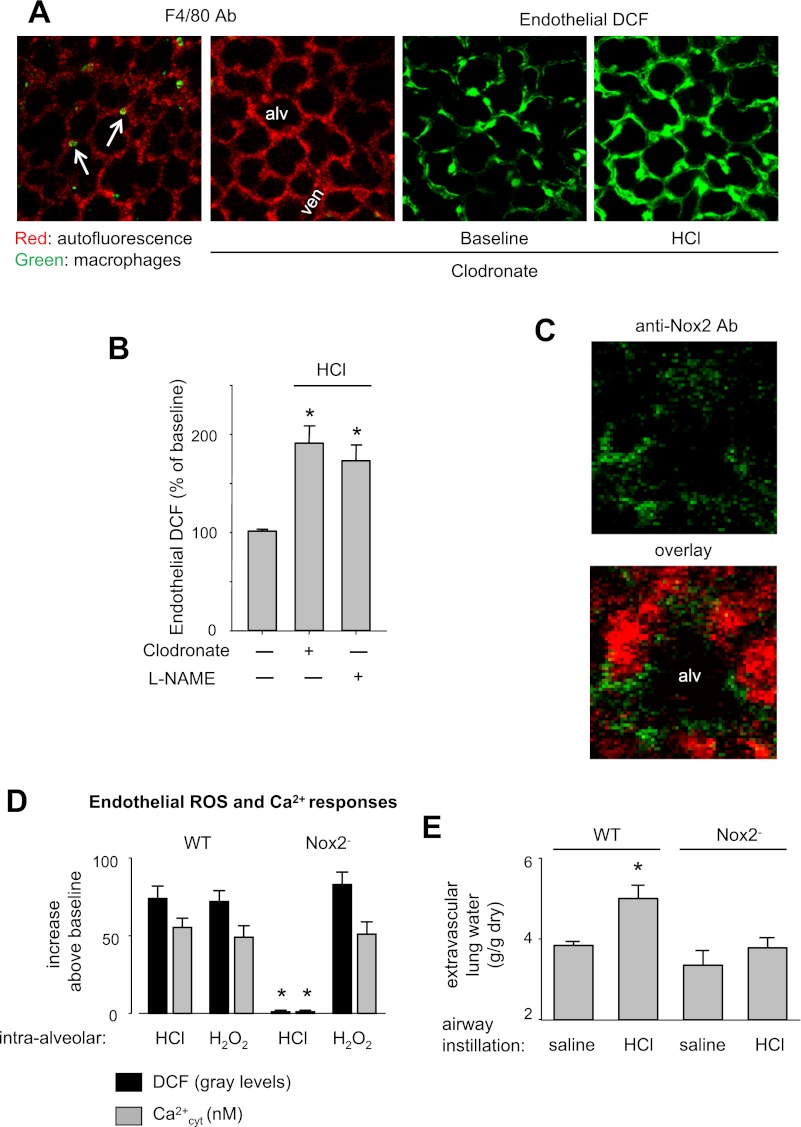

Because alveolar macrophages are implicated in acid-induced ALI (15), we depleted lung macrophages in mice by intra-tracheal instillation of clodronate-containing liposomes (11). To determine macrophage numbers by immunofluorescence of the macrophage-specific Ab F4/80 (35), we microinfused alveoli with the Ab. In untreated lungs, in each field of view we detected 7–8 macrophages/20 alveoli (Fig. 7A). Because clodronate treatment could cause patchy macrophage depletion, in the clodronate-treated group, we selected alveolar regions that were completely devoid of F4/80 fluorescence, and hence of macrophages (Fig. 7A). Microinjection of HCl in these macrophage-depleted alveoli induced increases of microvascular ROS (Fig. 7, A and B), suggesting that the ROS response was not due to alveolar macrophages.

Fig. 7.

Source of ROS. Alveolar HCl infusions were given at pH 1.5; Nox2−, NADPH oxidase knockout mice. A: images of a control lung (image on left) and a lung 24 h postairway instillation of clodronate-containing liposomes. Arrows point to F4/80-stained alveolar macrophages. Absence of macrophages after clodronate treatment is shown by lack of F4/80 antibody (Ab) staining (second from left). Images on right in green show endothelial DCF response to alveolar HCl infusion. Replicated 3 times. B: endothelial DCF response to 5-min microinfusions of acid (line) or buffer (first bar). Clodronate was given 24 h before the experiment, and NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME, 10 μM) was given by a 20-min intra-alveolar microinfusion immediately before the HCl infusion. Means ± SE; n = 3 lungs each; *P < 0.05 vs. buffer infusion. C: confocal images of a single alveolus (alv) show autofluorescence (red) and Nox2 expression (green) on the alveolar wall of wild-type (WT) mice. Replicated 3 times. D: responses shown are for 5-min intra-alveolar microinfusions of HCl or H2O2 (100 μM). n = 3 lungs each bar; P < 0.05 vs. WT. E: determinations made 2 h after intratracheal instillation of saline or HCl of pH 1.5 (2 ml/kg) in anesthetized mice. Means ± SE; n = 4 lungs each; *P < 0.05 vs. WT saline.

Nox2 role.

In situ immunofluorescence confirmed expression of Nox2 in alveolar epithelium of wild-type mice (Fig. 7C). Following alveolar HCl infusion, ROS and Ca2+ increases in the microvascular endothelium did not occur in Nox2-deficient mice (Fig. 7D). For positive control, we confirmed that alveolar injection of H2O2 was capable of increasing DCF fluorescence in the capillary endothelium of Nox2-deficient mice (Fig. 7D), ruling out the possibility that methodological errors accounted for the inhibitory responses.

Alveolar HCl injection did not affect BCECF fluorescence in the microvascular endothelium (data not shown). Thus, the pore-forming effect of alveolar HCl infusion was confined to the alveolus. Furthermore, the NOS inhibitor l-NAME did not affect the microvascular ROS response to alveolar acid (Fig. 7B), indicating that NO was not responsible for the increase of DCF fluorescence. Taken together, our findings indicate that Nox2 was the H2O2 source. Additionally, intratracheal HCl increased extravascular lung water in wild-type, but not in Nox2, knockout mice (Fig. 7E), consistent with the notion that ROS mediated the lung injury.

DISCUSSION

It is generally surmised that the ALI that follows acid aspiration results from acid-induced disruption of alveolar membranes. However, our findings indicate that direct contact of concentrated acid with alveoli itself does not lead to alveolar disruption because the alveolar epithelium rapidly self-repairs membrane pores formed as a consequence of the acid contact. The pores allowed cellular entry of FD4, but excluded entry of the much larger FD250, which has a molecular diameter of 23 nm (2), indicating that the pores were of molecular scale. The membrane resealing was robust since we could reload cytosolic dye in the postrepair phase in alveoli that had previously undergone the acid-induced pore formation and repair responses. To our knowledge, these findings are the first evidence that a major effect of the first contact of concentrated HCl with alveolar epithelium is the induction of transient pore formation and increased small solute permeability in the apical membrane.

This effect was not itself sufficient to induce alveolar edema, as we show in our studies in which tracer dextran introduced in perialveolar microvessels failed to reach the alveolus. However, the pore formation induced proinflammatory responses, as evident in the increased microvascular ROS. Hence, the pore formation initiated paracrine signaling between the alveolar epithelium and the microvascular endothelium. Catalase overexpression in the alveolar epithelium, or PEG-catalase infusion given in the alveoli or by perfusion, each blocked the increase of microvascular ROS, implicating H2O2 in the paracrine effect.

Alveoli express Nox2 (1) and generate ROS by Ca2+-dependent mechanisms (12). Accordingly, we could not elicit the microvascular ROS increase in mice lacking Nox2. Furthermore, depletion of extracellular Ca2+ in alveoli inhibited the acid-induced increase of microvascular ROS, implicating Ca2+ entry through the acid-induced membrane pores as the critical mechanism that induced the alveolar H2O2 release, which then diffused to adjoining microvessels.

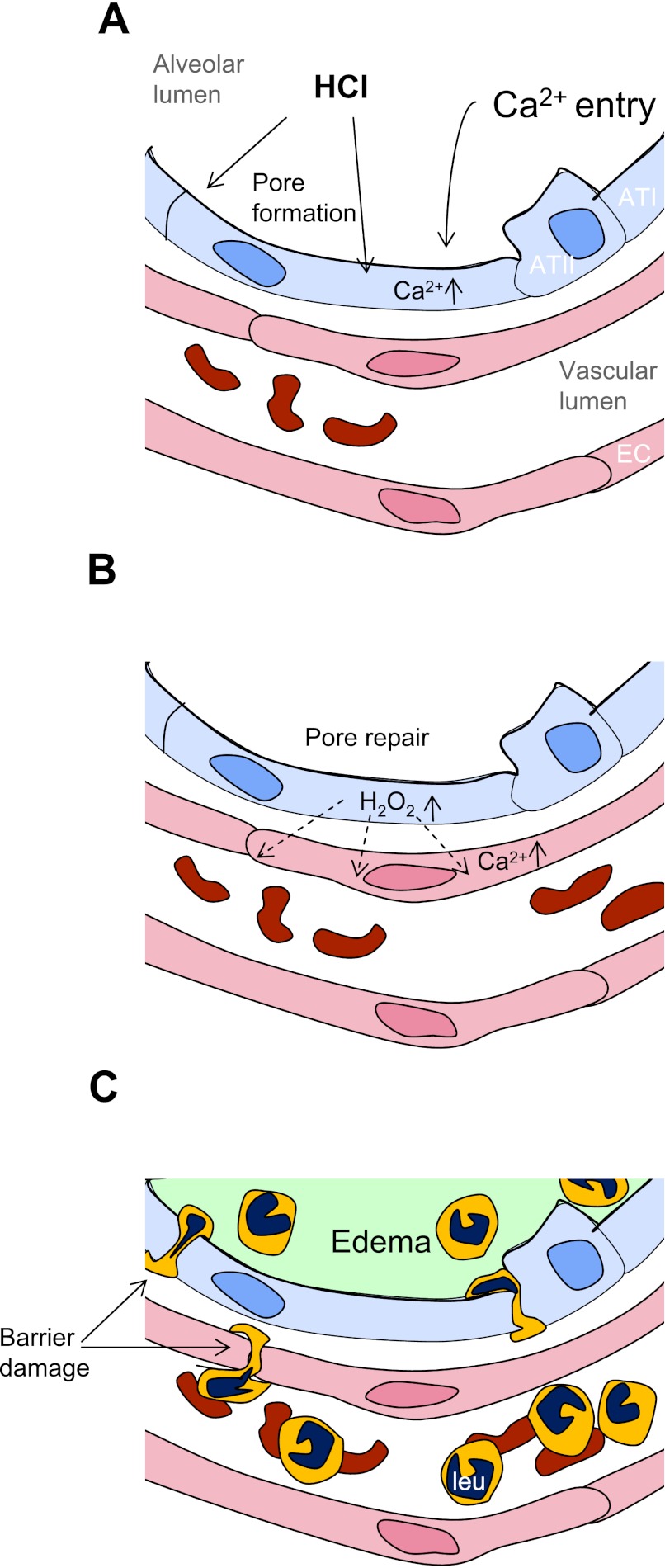

As we show in previous reports (14, 16, 25), an increase of lung microvascular H2O2 is a proinflammatory event that increases endothelial Ca2+, expression of leukocyte adhesion receptors, and leukocyte recruitment (16, 19, 25). Here, the paracrine diffusion of H2O2 from alveoli to microvessels also increased microvascular Ca2+, indicating that proinflammatory conditions were established in the microvasculature. The alveolar edema occurred with a delay of hours presumably because of the time taken to develop microvascular inflammatory responses, including leukocyte recruitment (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Sequence of events in acid-induced lung inflammation. ATI, alveolar type I cell; ATII, alveolar type II cell; EC, endothelial cell; leu, leukocyte. A: HCl contact with the alveolar epithelium causes pore formation and Ca2+ entry, increasing cytosolic Ca2+. B: pores reseal and the epithelium releases H2O2, which diffuses to the microvascular endothelium and increases endothelial Ca2+. C: endothelial Ca2+ increases initiate leukocyte recruitment and pulmonary edema formation.

Our findings suggest that chemical injury to the alveolar epithelial membrane recapitulates membrane resealing mechanisms previously identified only with mechanical damage (9, 23, 24, 32). Although damaged cell membranes are known to reseal, the reported data are due to relatively large mechanical disruptions caused by the insertion of mechanical probes of diameter 1–2 μm (8, 32). We affirm that membrane resealing processes are Ca2+ dependent and probably result from insertion of cytosolic vesicles at damaged sites (8).

We report here novel evidence that the alveolar epithelium in situ generates oxidative responses to acid contact. Alveolar macrophages have been implicated as a source of ROS in acid injury (15). However, here the ROS signaling was independent of macrophages since we replicated the findings in macrophage-depleted lungs. Our uncaging findings are the first evidence that alveolar epithelial cells are capable of Ca2+-dependent ROS generation that leads to rapid proinflammatory Ca2+ increases in the microvasculature. Taking all findings together, we propose that Ca2+ entry in the acid-permeabilized alveolar epithelium causes ROS production, leading to proinflammatory paracrine effects of H2O2. The extent to which signals upstream or downstream of the H2O2 production play a role in the inflammatory response needs further consideration.

Some procedural issues require consideration. We directly infused acid in the alveolus, whereas entry of aspirated acid occurs at the trachea. We confirmed that HCl instilled intratracheally reaches the lung periphery (data not shown); hence, direct introduction of acid in the alveolus models acid aspiration. In fact, the similarity is indicated by the pH dependence of the permeability effect. Here, the full effect occurred at pH <1.5, a mild effect was evident at pH of 2–3, while no effect occurred at pH >4. A similar concentration-dependent effect has been reported in that acid-induced ALI occurs only at pH <2 (22), affirming the relevance of our findings to the global acid effect in lung.

DCF fluorescence may result from light-induced photo-oxidation during image acquisition. Photo-activated release of a free radical from DCF may form superoxide on being oxidized by oxygen back to the parent dye (28). We ruled out these potential artifacts since baseline fluorescence did not increase progressively, as would be the case if light-induced DCF oxidation occurs continuously. Fluorescence of DCF might unspecifically increase due to NO generation. However, the acid-induced increase in microvascular DCF fluorescence was completely inhibited in the presence of PEG-catalase and not changed in the presence of l-NAME. These findings indicate that NO does not induce the acid-induced DCF response.

In summary, we show here that the contact with concentrated acid forms membrane pores in the alveolar epithelium. Although the pores reseal, they induce a sequence of events in which Ca2+ enters the cell, releases H2O2, which diffuses to the adjoining microvessels, inducing proinflammatory responses (Fig. 8). We recognize that, in the clinical syndrome of aspiration-induced ALI, the aspirated fluid is complex, especially since it includes particulate matter (17), and is therefore likely to induce complex alveolar effects. Although in our approach we consider the effects of acid alone, we suggest that, to the extent that aspirated fluid reaches alveoli at high acidity, our findings might be relevant to the aspiration syndrome. To this extent, therapeutic strategies for aspiration ALI might consider inhibiting the induced paracrine signaling between alveoli and blood vessels. Our findings support such a strategy in that the application of PEG-catalase effectively inhibited the paracrine effect. In conclusion, we show that the alveolar epithelial membrane provides a robust, resealing barrier against the toxicity of concentrated acid. The extent to which these resealing properties resist alveolar damage in other settings of lung injury requires further consideration.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-36024, HL-69514, HL-64896, and HL-78645.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: K.W., E.M., and M.N.I. performed experiments; K.W., E.M., and M.N.I. analyzed data; K.W., E.M., and J.B. interpreted results of experiments; K.W. and E.M. prepared figures; K.W. and J.B. drafted manuscript; K.W. and J.B. edited and revised manuscript; K.W., E.M., M.N.I., and J.B. approved final version of manuscript; J.B. conception and design of research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Jens Lindert assisted with the experiments.

Note: Dr. Jens Lindert was originally the first author but was removed from the author list by the corresponding author because he did not participate in the revision of the manuscript or approve the final version. All attempts to contact Dr. Lindert during the revision process have been unsuccessful.

REFERENCES

- 1. Archer SL, Reeve HL, Michelakis E, Puttagunta L, Waite R, Nelson DP, Dinauer MC, Weir EK. O2 sensing is preserved in mice lacking the gp91 phox subunit of NADPH oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 7944– 7949, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Armstrong JK, Wenby RB, Meiselman HJ, Fisher TC. The hydrodynamic radii of macromolecules and their effect on red blood cell aggregation. Biophys J 87: 4259– 4270, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ashino Y, Ying X, Dobbs LG, Bhattacharya J. [Ca2+]i oscillations regulate type II cell exocytosis in the pulmonary alveolus. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 279: L5– L13, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Atuma C, Strugala V, Allen A, Holm L. The adherent gastrointestinal mucus gel layer: thickness and physical state in vivo. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 280: G922– G929, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bai J, Rodriguez AM, Melendez JA, Cederbaum AI. Overexpression of catalase in cytosolic or mitochondrial compartment protects HepG2 cells against oxidative injury. J Biol Chem 274: 26217– 26224, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bastacky J, Lee CY, Goerke J, Koushafar H, Yager D, Kenaga L, Speed TP, Chen Y, Clements JA. Alveolar lining layer is thin and continuous: low-temperature scanning electron microscopy of rat lung. J Appl Physiol 79: 1615– 1628, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beutler B, Rietschel ET. Innate immune sensing and its roots: the story of endotoxin. Nat Rev Immunol 3: 169– 176, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bi GQ, Alderton JM, Steinhardt RA. Calcium-regulated exocytosis is required for cell membrane resealing. J Cell Biol 131: 1747– 1758, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fisher JL, Levitan I, Margulies SS. Plasma membrane surface increases with tonic stretch of alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 31: 200– 208, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Folkesson HG, Matthay MA, Hebert CA, Broaddus VC. Acid aspiration-induced lung injury in rabbits is mediated by interleukin-8-dependent mechanisms. J Clin Invest 96: 107– 116, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Frank JA, Wray CM, McAuley DF, Schwendener R, Matthay MA. Alveolar macrophages contribute to alveolar barrier dysfunction in ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 291: L1191– L1198, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Granfeldt D, Samuelsson M, Karlsson A. Capacitative Ca2+ influx and activation of the neutrophil respiratory burst. Different regulation of plasma membrane- and granule-localized NADPH-oxidase. J Leukoc Biol 71: 611– 617, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ichimura H, Parthasarathi K, Lindert J, Bhattacharya J. Lung surfactant secretion by interalveolar Ca2+ signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 291: L596– L601, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ichimura H, Parthasarathi K, Quadri S, Issekutz AC, Bhattacharya J. Mechano-oxidative coupling by mitochondria induces proinflammatory responses in lung venular capillaries. J Clin Invest 111: 691– 699, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Imai Y, Kuba K, Neely GG, Yaghubian-Malhami R, Perkmann T, van Loo G, Ermolaeva M, Veldhuizen R, Leung YH, Wang H, Liu H, Sun Y, Pasparakis M, Kopf M, Mech C, Bavari S, Peiris JS, Slutsky AS, Akira S, Hultqvist M, Holmdahl R, Nicholls J, Jiang C, Binder CJ, Penninger JM. Identification of oxidative stress and Toll-like receptor 4 signaling as a key pathway of acute lung injury. Cell 133: 235– 249, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kiefmann R, Rifkind JM, Nagababu E, Bhattacharya J. Red blood cells induce hypoxic lung inflammation. Blood 111: 5205– 5214, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Knight PR, Rutter T, Tait AR, Coleman E, Johnson K. Pathogenesis of gastric particulate lung injury: a comparison and interaction with acidic pneumonitis. Anesth Analg 77: 754– 760, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kuebler WM, Parthasarathi K, Lindert J, Bhattacharya J. Real-time lung microscopy. J Appl Physiol 102: 1255– 1264, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kuebler WM, Parthasarathi K, Wang PM, Bhattacharya J. A novel signaling mechanism between gas and blood compartments of the lung. J Clin Invest 105: 905– 913, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lindert J, Perlman CE, Parthasarathi K, Bhattacharya J. Chloride-dependent secretion of alveolar wall liquid determined by optical-sectioning microscopy. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 36: 688– 696, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marik PE. Aspiration pneumonitis and aspiration pneumonia. N Engl J Med 344: 665– 671, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Matute-Bello G, Frevert CW, Martin TR. Animal models of acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L379– L399, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McNeil PL, Steinhardt RA. Plasma membrane disruption: repair, prevention, adaptation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 19: 697– 731, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oeckler RA, Hubmayr RD. Cell wounding and repair in ventilator injured lungs. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 163: 44– 53, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Parthasarathi K, Ichimura H, Quadri S, Issekutz A, Bhattacharya J. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species regulate spatial profile of proinflammatory responses in lung venular capillaries. J Immunol 169: 7078– 7086, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ragette R, Fu C, Bhattacharya J. Barrier effects of hyperosmolar signaling in microvascular endothelium of rat lung. J Clin Invest 100: 685– 692, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rink TJ, Tsien RY, Pozzan T. Cytoplasmic pH and free Mg2+ in lymphocytes. J Cell Biol 95: 189– 196, 1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rota C, Fann YC, Mason RP. Phenoxyl free radical formation during the oxidation of the fluorescent dye 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein by horseradish peroxidase. Possible consequences for oxidative stress measurements. J Biol Chem 274: 28161– 28168, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Selinger SL, Bland RD, Demling RH, Staub NC. Distribution volumes of [131I]albumin, [14C]sucrose, and 36Cl in sheep lung. J Appl Physiol 39: 773– 779, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shigemitsu H, Afshar K. Aspiration pneumonias: under-diagnosed and under-treated. Curr Opin Pulm Med 13: 192– 198, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shuvaev VV, Muzykantov VR. Targeted modulation of reactive oxygen species in the vascular endothelium. J Control Release 153: 56– 63, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Steinhardt RA, Bi G, Alderton JM. Cell membrane resealing by a vesicular mechanism similar to neurotransmitter release. Science 263: 390– 393, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Togbe D, Schnyder-Candrian S, Schnyder B, Doz E, Noulin N, Janot L, Secher T, Gasse P, Lima C, Coelho FR, Vasseur V, Erard F, Ryffel B, Couillin I, Moser R. Toll-like receptor and tumour necrosis factor dependent endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. Int J Exp Pathol 88: 387– 391, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. van Westerloo DJ, Knapp S, van't Veer C, Buurman WA, de Vos AF, Florquin S, van der Poll T. Aspiration pneumonitis primes the host for an exaggerated inflammatory response during pneumonia. Crit Care Med 33: 1770– 1778, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. von Garnier C, Filgueira L, Wikstrom M, Smith M, Thomas JA, Strickland DH, Holt PG, Stumbles PA. Anatomical location determines the distribution and function of dendritic cells and other APCs in the respiratory tract. J Immunol 175: 1609– 1618, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Weiser MR, Pechet TT, Williams JP, Ma M, Frenette PS, Moore FD, Kobzik L, Hines RO, Wagner DD, Carroll MC, Hechtman HB. Experimental murine acid aspiration injury is mediated by neutrophils and the alternative complement pathway. J Appl Physiol 83: 1090– 1095, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zarbock A, Distasi MR, Smith E, Sanders JM, Kronke G, Harry BL, von Vietinghoff S, Buscher K, Nadler JL, Ley K. Improved survival and reduced vascular permeability by eliminating or blocking 12/15-lipoxygenase in mouse models of acute lung injury (ALI). J Immunol 183: 4715– 4722, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]