Abstract

We have shown that adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells from placental ischemia (reduction in uteroplacental perfusion, RUPP) rats causes hypertension and elevated inflammatory cytokines during pregnancy. In this study we tested the hypothesis that adoptive transfer of RUPP CD4+ T cells was associated with endothelin-1 activation as a mechanism to increase blood pressure during pregnancy. CD4+ T cells from RUPP or normal pregnant (NP) rats were adoptively transferred into NP rats on gestational day 13. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was analyzed on gestational day 19, and tissues were collected for endothelin-1 analysis. MAP increased in placental ischemic RUPP rats versus NP rats (124.1 ± 3 vs. 96.2 ± 3 mmHg; P = 0.0001) and increased in NP recipients of RUPP CD4+ T cells (117.8 ± 2 mmHg; P = 0.001 compared with NP). Adoptive transfer of RUPP CD4+ T cells increased placental preproendothelin-1 mRNA 2.1-fold compared with NP CD4+ T cell rats and 1.7-fold compared with NP. Endothelin-1 secretion from endothelial cells exposed to NP rat serum was 52.2 ± 1.9 pg·mg−1·ml−1, 77.5 ± 4.3 pg·mg−1·ml−1 with RUPP rat serum (P = 0.0003); 47.2 ± .16 pg·mg−1·ml−1 with NP+NP CD4+ T cell serum, and 62.2 ± 2.1 pg·mg−1·ml−1 with NP+RUPP CD4+ T cell serum (P = 0.002). To test the role of endothelin-1 in RUPP CD4+ T cell-induced hypertension, pregnant rats were treated with an endothelin A (ETA) receptor antagonist (ABT-627, 5 mg/kg) via drinking water. MAP was 92 ± 2 mmHg in NP+ETA blockade and 108 ± 3 mmHg in RUPP+ETA blockade; 95 ± 5 mmHg in NP+NP CD4+ T cells+ETA blockade and 102 ± 2 mmHg in NP+RUPP CD4+ T cells+ETA blockade. These data indicate the importance of endothelin-1 activation to cause hypertension via chronic exposure to activated CD4+ T cells in response to placental ischemia.

Keywords: pregnancy, T helper cells, placental ischemia

preeclampsia, a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, clinically characterized by new onset maternal hypertension and proteinuria after 20 wk gestation, typically affects 2–7% of pregnancies in the United States and contributes to almost 20% of maternal deaths in the United States (18, 22). Hypertension in pregnancy, which occurs in response to placental ischemia, is associated with endothelial dysfunction, elevated circulating and placental inflammatory cytokines, and, in some cases, intrauterine growth restriction (2, 4, 7, 12). One hallmark of endothelial dysfunction is activation of the endothelin-1 (ET-1) pathway. Elevation of the vasoconstrictor peptide ET-1 and activation of the endothelin A (ETA) receptor mediates vasoconstriction and elevated blood pressure. This serves as one mechanism of hypertension in response to placental ischemia that is hypothesized to play a role in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia (5, 22–24). A reduction in uteroplacental perfusion (RUPP), thought to be an initiating event in preeclampsia, contributes to wide-spread dysfunction of the maternal vascular endothelium during pregnancy (5, 23, 24). Serum from women with preeclampsia and serum from animal models of placental ischemia induced-hypertension cause endothelial activation/dysfunction, thereby suggesting the importance of circulating factors stimulated in response to placental ischemia to impact the maternal vasculature (15, 21, 25, 29). In recent years, much obstetric research has focused on identifying components of the immune system that are activated and play a role in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. We now know that preeclampsia is associated with elevated inflammatory cytokines, activation of T lymphocytes, and B lymphocyte secreting antibodies that activate receptors that are important in regulating sodium and water homeostasis, such as the angiotensin II type I receptor (9, 14, 15, 26, 29).

Our laboratory recently reported that placental ischemia (RUPP) increases circulating CD4+ T cells that secrete significantly more tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and the anti-angiogenic factor soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1) compared with normal pregnant (NP) rats (29). In addition, adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells from RUPP rats into NP rats increased blood pressure and is associated with an increase in inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α, interleukin-6, interleukin-17, and sFlt-1, similar to that seen with the RUPP model (29). Most recently, we demonstrated agonistic autoantibodies to the angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1-AA) to be increased in response to adoptive transfer of RUPP CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, the hypertension in this model is attenuated by either AT1 receptor blockade or B cell depletion in NP recipient rats (30). This study demonstrates the importance of CD4+ T cells in response to placental ischemia to cause elevations in blood pressure potentially by stimulating the AT1-AA from NP recipient rats. We have previously shown the importance of the AT1-AA to mediate blood pressure increases during pregnancy by stimulating production of ET-1 and activation of the ETA receptors (8). Furthermore, we have shown the importance of endogenous AT1-AA in RUPP rats to stimulate ET-1 activation as one mechanism of causing hypertension in response to placental ischemia (30). In addition, we have shown an important role for TNF-α to stimulate ET-1 as one mechanism of hypertension in response to RUPP during pregnancy (13).

Therefore, the current study was designed to determine a role for ET-1 activation as a potential mechanism of hypertension in response to adoptive transfer of RUPP-stimulated CD4+ T cells. We postulate that in the setting of placenta ischemia, B and T lymphocytes increase circulating and/or placental levels of inflammatory cytokines, sFlt-1, or the AT1-AA as mechanisms of ET-1 activation (11, 13, 15, 16, 24, 29). These individual mechanisms act in concert to mediate renal dysfunction and increase blood pressure during pregnancy (11). Therefore, the first objective of the current study was to determine whether local ET-1 mRNA and vascular ET-1 were stimulated in NP recipient rats of RUPP CD4+ T cells. To achieve this goal we repeated adoptive transfer studies of RUPP CD4+ T cells into NP recipient rats following the previously described method and determined ET-1 mRNA transcript and secretion (29). The second objective was to determine whether ET-1 elevated in this model mediates the hypertension. This objective was achieved by comparing control blood pressures with those in experimental groups treated chronically with the selective ETA receptor antagonist ABT-627.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All studies were performed in 250 g timed-pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN). Animals were housed in a temperature-controlled room with a 12 h:12 h light-dark cycle. All experimental procedures in this study were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for use and care of animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Protocol 1: reduction of uterine perfusion pressure.

On gestational day 14 under isoflurane anesthesia NP rats underwent a RUPP with the application of a constrictive silver clip (0.203 mm) to the aorta superior to the iliac bifurcation performed while ovarian collateral circulation to the uterus was reduced with restrictive clips (0.100 mm) to the bilateral uterine arcades at the ovarian end (6, 15, 29).

Adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells into NP recipient rats.

At gestational day 13, 1 × 106 CD4+ T cells/100 μl saline were administered to NP rats via intraperitoneal injection (29). Briefly, spleens from NP and RUPP rats were isolated at the time of euthanasia on gestational day 19 and immediately placed in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.0. Spleens were homogenized with RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and filtered through a 100-μm cell strainer to obtain single cell suspensions. CD4+ T lymphocytes were isolated from the splenocytes via magnetic separation using CD4+ Dynabeads according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, splenocytes were incubated with 1.85 mg of biotinylated CD4 per 5 × 106 cells on ice for 30 min. The cells were centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 RPM, and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was resuspended with 1 ml of RPMI and incubated with Dynabeads for 30 min on ice. The Eppendorf containing the cell-Dynabead mix was placed in a magnet for 1 min, and the CD4− cells were collected. One milliliter of RPMI was added to the cell pellet and the collection of CD4− cells was repeated. Cell release buffer, provided by the manufacture, was added to the cell pellet and mixed for 30 min at room temperature. The Eppendorf containing the cell-Dynabead mix was placed on a magnet for 1 min and the CD4+ cells were released from the beads into the RPMI and collected. Once released from the Dynabeads, CD4+ T cells were washed in PBS and cultured in RPMI 1640 containing HEPES (25 mM), glutamine (2 mM), Pen/Strep (100 U/ml), 1.022 ng/ml IL-2 (1), and 4 ng/ml IL-12 (3) for 24 h at 5% CO2 at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere. After centrifugation, cell pellets were washed with saline and adjusted to 1 × 106 cells/100 μl saline for injection into recipient NP rats (29).

Determination of MAP in control and NP recipient rats.

Under isoflurane anesthesia on day 18 of gestation, carotid arterial catheters were inserted for mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) measurements. The catheters inserted are V3 tubing (SCI) that is tunneled to the back of the neck and exteriorized. On day 19 of gestation arterial blood pressure was analyzed after the rats were placed in individual restraining cages. Arterial pressure was monitored with a pressure transducer (Cobe III Transducer CDX Sema) and recorded continuously after a 1-h stabilization period. The four groups examined were as follows: NP rats, NP rats injected with NP CD4+ T cells (NP + NP CD4+ T cells), RUPP rats, and NP rats injected with CD4+ RUPP T cells (NP + RUPP CD4+ T cells). Because adoptive transfer of NP or RUPP CD4+ T cells into virgin rats has been shown to not increase blood pressure, these groups were not examined in the current study (29).

Determination of placental and renal preproendothelin mRNA levels.

The placenta, cortex, and medulla of the kidneys were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Total RNA was extracted using the Qiagen kit after the tissue was crushed in liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle. The isolation procedure was then performed as outlined in the instructions provided by the manufacturer. cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of RNA with Bio-Rad Iscript cDNA reverse transcriptase and real-time PCR was performed using the Bio-Rad Sybre Green Supermix and iCycler. The following primer sequences provided by Life technologies were used for PPET as previously described: forward 1, ctaggtctaagcgatccttg, and reverse 1, tctttgtctgcttggc (8, 10, 15). Levels of mRNA were calculated using the mathematical formula for 2−ΔΔCt (2avg. Ct gene of interest − avg Ct beta actin) recommended by Applied Biosystems (Applied Biosystems User Bulletin, No. 2, 1997).

Endothelial cell endothelin-1 production.

The experimental protocol to determine whether adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells from RUPP rats would cause an increase in vascular (human umbilical vein endothelial cells, HUVEC) secretion of ET-1, therefore, the HUVEC bioassay was performed as previously shown (13, 15, 25). HUVEC passages 2–3 were cultured in 50:50 DMEM/M199 (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and 1% antimycotic-antibiotic solution (Invitrogen) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2-20% O2-75% N2 at 37°C. Once 70% confluence was obtained, cells were incubated with serum-free media for 48 h. After 48 h in serum-free media, cells were washed and exposed to experimental media (500 μl of serum from experimental rats + 500 μl serum-free cell culture media/well) for a period of 24 h. All experiments were done in duplicate wells with n = 3–6 rats per group. After the 24-h incubation period with experimental media, the experimental medium was removed, the cells were washed with 2 ml of Hanks' balanced salt solution (Invitrogen), and 1.5 ml/well of fresh serum-free media were placed on the cells. After 6 h, 1 ml of medum was collected and 1 ml of serum-free medium was added to replenish the total media volume. At 18 h, 1 ml of medium was removed to determine whether ET-1 secretion increased with time. At this point cells were trypsinized and collected for total protein measurement to normalize ET-1 secretion (13, 15, 25).

Determination of endothelin concentration.

Endothelin was determined using 100 μl of collected HUVEC media and measured using the ET-1 Quantikine ELISA kit from R&D systems (8, 10, 15). According to the manufacturer reports the assay displayed a sensitivity of 0.023 to 0.102 pg/ml, inter-assay variability of 8.9%, and intra-assay variability of 3.4%.

Protocol 2: effect of ETA receptor antagonist on CD4+ RUPP T cell-induced hypertension.

This protocol was performed to determine whether ETA receptor-blockade attenuated CD4+ RUPP T cell-induced hypertension during pregnancy. CD4+ T cells from RUPP rats were adoptively transferred to NP rats on day 13 of gestation. On day 14 of gestation rats were orally treated (drinking water) with the ETA receptor antagonist (ABT-627, 5 mg/kg) until day 19 of gestation. NP and RUPP rats served as controls. Arterial pressure was determined among NP + ETA, RUPP + ETA, NP + NP CD4+ T cells + ETA, and NP + RUPP CD4+ T cells + ETA on day 19 of gestation (10, 11). Arterial pressure was determined in all groups of pregnant rats at day 19 of gestation as previously described in protocol 1.

Statistical analysis.

All data are expressed as means ± SE. Differences between control and experimental groups were analyzed via one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and post-hoc analyses were obtained through Bonferroni post hoc test. Student's t-test was used to compare groups treated with the ETA antagonist to their respective untreated groups. All reported P values are indicative of post hoc analysis with the exception of the renal cortical and medullary values, which are representative of the overall effect of treatment group by ANOVA. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Protocol 1: effect of adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells into NP recipients' on MAP.

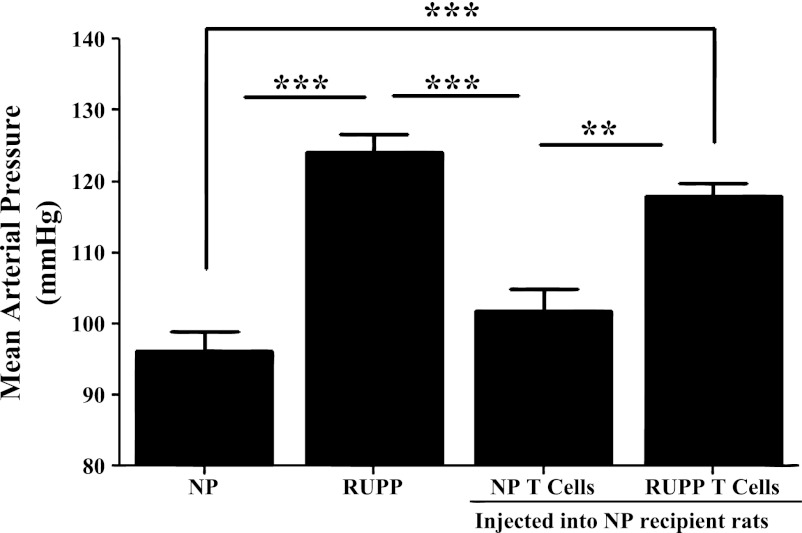

As seen with previous studies, (13, 15, 29) animals in the RUPP group (n = 18) had significant increases in MAP compared with NP rats (n = 15) (124.1 ± 3 RUPP vs. 96 ± 3 mmHg NP; P = 0.0001) and NP + NP CD4+ T cell rats (n = 7; 101.9 ± 3 mmHg; P = 0.0001; Fig. 1). Adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells from RUPP rats into NP rats resulted in significant increases in arterial pressure (n = 6; 117.8 ± 2 mmHg) compared with NP controls (P = 0.0001) and compared with NP + NP CD4+ T cell recipient rats (n = 7; P = 0.0013; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Adoptive transfer of reduction in uteroplacental perfusion (RUPP) CD4+ T cells into normal pregnant (NP) rats increases blood pressure. Blood pressure results (mmHg) in NP (n = 15), RUPP (n = 18), NP + NP CD4+ T cells (n = 7), and NP + RUPP CD4+ T cells (n = 6) on day 19 of gestation are shown. Placental ischemia in the RUPP rat significantly increase mean arterial pressure (MAP) compared with NP and NP + NP CD4+ T cell rats. NP recipients of RUPP CD4+ T cells had significantly increased MAP compared with NP + NP CD4+ T cell rats and NP rats. **P < 0.005. ***P < 0.0005.

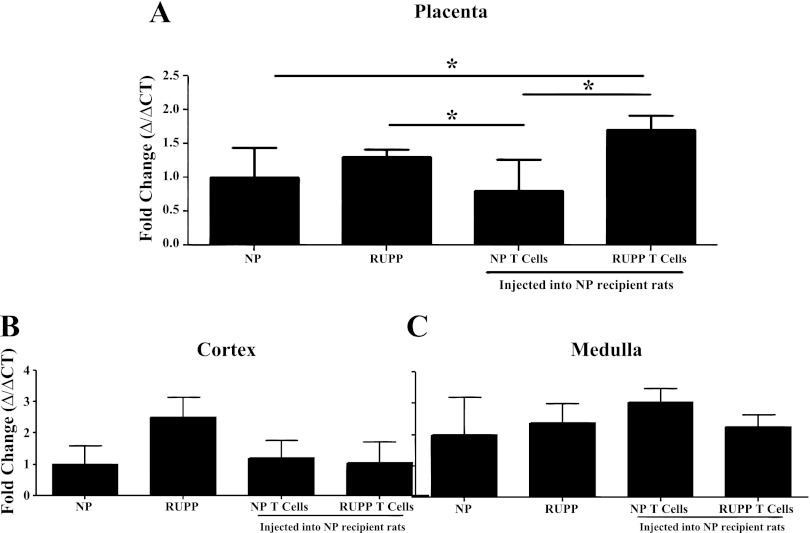

Adoptive transfer of RUPP CD4+ T cells increases placental production of tissue endothelin.

Utilizing real-time PCR, we have previously shown that renal and placental preproendothelin is increased in RUPP rats compared with NP rats (10). Therefore, via real-time PCR we measured preproendothelin in placenta and renal cortex and medulla of NP controls, RUPPs, and NP recipients of NP CD4+ T cells and RUPP CD4+ T cells. Preproendothelin was increased 1.7-fold in the placenta from NP + RUPP CD4+ T cells rats (n = 12) compared with NP rats (n = 8; P = 0.03), 2.1-fold compared with NP recipients of NP CD4+ T cells (n = 6; P = 0.02), and 1.2-fold compared with RUPP rats (n = 8; P = 0.66, Fig. 2A). In keeping with previous studies, preproendothelin was increased in RUPP rats 1.3-fold compared with NP rats (P = 0.06) and to NP recipients of NP CD4+ T cells (P = 0.02, Fig. 2A). Interestingly, there were no significant increases in mRNA preproendothelin expression in the renal cortex (P = 0.293) or the medulla (P = 0.364) due to the RUPP procedure or adoptive transfer of RUPP CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2, B and C).

Fig. 2.

Adoptive transfer of RUPP CD4+ T cell increased placental endothelin-1 (ET-1) mRNA transcript. ET-1 transcript was quantitated by real-time PCR in placentas (A), renal cortex (B), and medulla (C) from NP (n = 8), RUPP (n = 8), NP + NP CD4+ T cells (n = 6), and NP + RUPP CD4+ T cells (n = 12). Placental ischemia in the RUPP rat significantly increased placental ET-1 mRNA transcript compared with NP + NP CD4+ T cell rats. Adoptive transfer of RUPP CD4+ T cells into NP recipients significantly increased placental mRNA ET-1 compared with NP rats and NP + NP CD4+ T cell rats. *P < 0.05.

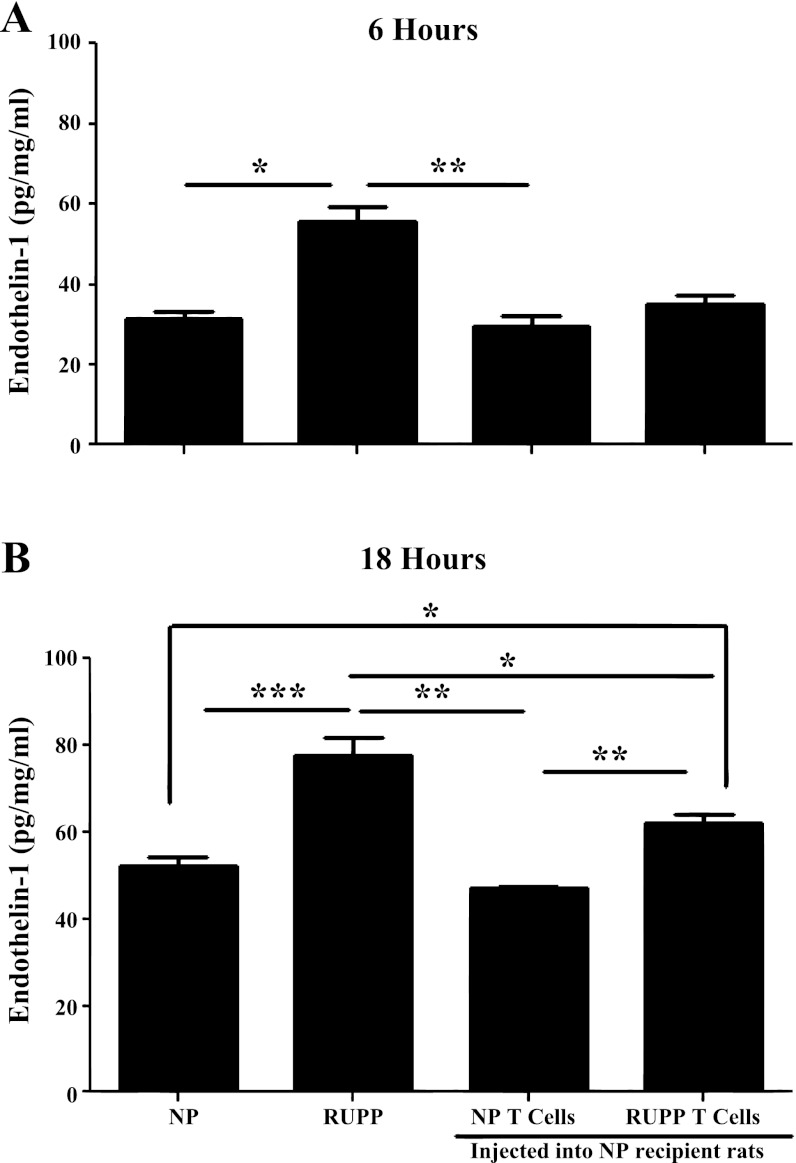

HUVEC ET-1 secretion is increased in response to adoptive transfer of RUPP CD4+ T cells.

Previous studies have demonstrated a twofold increase in ET-1 secretion from endothelial cells in response to serum from RUPP rats compared with serum from NP rats (8, 15). To examine the role of adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells in mediating endothelial activation and dysfunction, we exposed HUVECs to serum collected from control NP and RUPP rats and serum from rats adoptively transferred CD4+ T cells. Samples were collected at 6 and 18 h postexposure to rat serum. At 6 h, ET-1 response to serum from RUPP rats (n = 6) is significantly increased compared with the ET-1 response of HUVECs to serum from NP rats (n = 6; P = 0.028) and NP + NP CD4+ T cell rats (n = 3, P = 0.002; Fig. 3). The ET-1 response to serum from NP recipients of RUPP CD4+ T cells was not significantly increased at 6 h compared with NP rats (P = 0.27) or NP + NP CD4+ T cell rats (P = 0.17; Fig. 3). Importantly, at 18 h, serum from adoptive transfer recipient rats of RUPP CD4+ T cells significantly increased the ET-1 response compared with NP rats (P = 0.017) and NP + NP CD4+ T cell rats (n = 3; P = 0.002; Fig. 3). The ET-1 response from RUPP serum remained significantly increased compared with NP rats (P = 0.0003), NP + NP CD4+ T cell rats (P = 0.002), and NP + RUPP CD4+ T cell rats (P = 0.05; Fig. 3). These results indicate RUPP CD4+ T cells stimulated in response to placental ischemia induce endothelial cell secretion of ET-1, which may increase MAP via activation of the ETA receptor.

Fig. 3.

Adoptive transfer of RUPP CD4+ T cells increased endothelial ET-1 secretion from cultured endothelial cells. ET-1 secretion from human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) incubated with RUPP (n = 6) serum after 6 h is significantly higher than ET-1 secretion from HUVECs incubated with serum from NP (n = 6) or NP + NP CD4+ T cell rats (n = 3) (A). However, after 18 h (B), ET-1 secretion from HUVECs incubated with RUPP serum is significantly higher than ET-1 secretion from HUVECs incubated with serum from other groups. ET-1 secretion from HUVECs incubated with serum from NP + RUPP CD4+ T cells (n = 3) is significantly higher than ET-1 secretion from HUVECs incubated with serum from NP or NP recipients of NP CD4+ T cell rats after 18 h. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005; ***P < 0.0005.

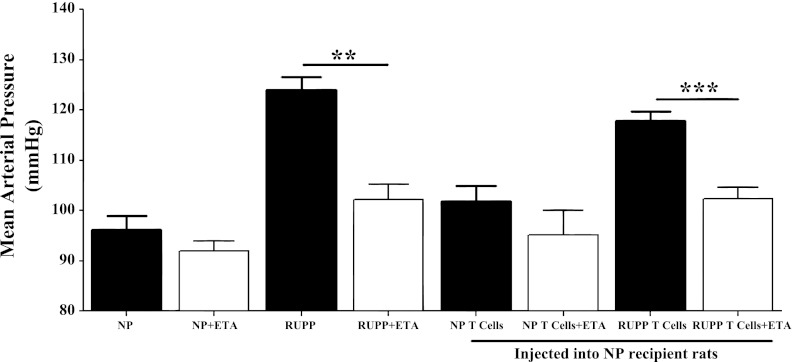

Protocol 2: effect of ETA receptor antagonist on RUPP CD4+ T cell-induced hypertension.

This protocol was performed to examine the effect of ETA receptor activation with hypertension in response to CD4+ T cells stimulated during placental ischemia. The selective ETA receptor antagonist (ABT-627) was administered for 5 days to NP and RUPP control rats along with adoptive transfer recipient rats of CD4+ T cells from either NP or RUPP rats. In keeping with previous studies, administration of an ETA receptor antagonist attenuated placenta ischemic-induced hypertension in the RUPP rats (n = 4; 102.3 ± 3 mmHg) compared with untreated RUPP rats (P = 0.001) and reached levels comparable to NP controls (P = 0.29, Fig. 4 10). Additionally, the hypertensive response due to adoptive transfer of RUPP CD4+ T cells was attenuated due to ETA receptor blockade (n = 7) compared with untreated NP recipients of RUPP CD4+ T cells (102.3 ± 2 vs. 117.8 ± 2 mmHg; P = 0.0003; Fig. 4). Whereas ETA receptor blockade did not fully attenuate the hypertensive response due to adoptive transfer of RUPP CD4+ T cells, the MAP was comparable to untreated NP recipients of NP CD4+ T cells (P = 0.91), untreated NP controls (P = 0.18), and RUPP rats treated with an ETA antagonist (P = 0.99; Fig. 4). MAP in NP recipients of NP CD4+ T cells treated with an ETA receptor antagonist (n = 5) was comparable to untreated NP + NP CD4+ T cell rats (95.2 ± 4.7 vs. 102 ± 3 mmHg, P = 0.244) and NP control rats (P = 0.857, Fig. 3).

Fig. 4.

Administration of endothelin A (ETA) receptor. Antagonist attenuates increases in blood pressure due to adoptive transfer of RUPP CD4+T cells are shown. Blood pressure results (mmHg) in NP, RUPP, NP + NP CD4+ T cells, and NP + RUPP CD4+ T cells on day 19 of gestation are also shown (protocol 1). Black bars are representative of MAP from protocol 1; white bars are representative of MAP from protocol 2. Protocol 2: NP+ ETA (n = 4), RUPP+ ETA (n = 4), NP + NP CD4+ T cells+ ETA (n = 75), and NP + RUPP CD4+ T cells+ ETA (n = 7). Hypertension is attenuated after an ETA receptor antagonist is administered to RUPP rats (compared with untreated RUPP rats) or NP recipient rats of RUPP CD4+ T cells (compared with untreated RUPP CD4+ T cell rats). **P < 0.05; ***P < 0.0005.

DISCUSSION

Alterations in endothelial cell function by circulating agents produced by the ischemic placenta have been proposed to be early steps in the evolution of developing preeclampsia. Several studies have been performed to demonstrate that sera from preeclamptic women and animal models of preeclampsia cause endothelial cell activation (21, 25). Studies from our laboratory have demonstrated several culprits stimulated in response to placental ischemia to subsequently activate the ET-1 system as an important mechanism of hypertension during pregnancy (8, 10, 11, 17, 27). We recently reported that infusion of rat AT1-AA into NP rats increases blood pressure, the anti-angiogenic factor sFlt-1, and sEndoglin and increased local transcription of the potent vasoconstrictor peptide ET-1 (19, 20). Furthermore, AT1-AA-induced hypertension was attenuated by ETA receptor blockade. Subsequently, we evaluated the importance of endogenously generated AT1-AA in mediating hypertension in response to placental ischemia by administering Rituximab, a B lymphocyte-depleting agent that significantly blunted hypertension, AT1-AA secretion, and ET-1 production in RUPP placental ischemic rats (15).

Most recently we have demonstrated a role for CD4+ T cells to cause increased blood pressure and decreased glomerular filtration rate, accompanied by elevated TNF-α and sFLt-1 and AT1-AA in NP recipient rats of RUPP CD4+ T cells (29, 30). Furthermore, previous studies have shown an important role for ETA receptor blockade in attenuating hypertension in response to placental ischemia and administration of TNF-α, sFlt-1, and AT1-AA (8, 10, 11, 17). Therefore, a logical extension of our studies was to determine a role for the ET-1 system to mediate hypertension in response to CD4+ T cells stimulated by placental ischemia. In the current study we examined ET-1 in response to RUPP CD4+ T cells and tested the importance of ET-1 to activate ETA receptors as a mechanism of hypertension during pregnancy by administrating an ETA receptor antagonist to NP recipient rats of RUPP CD4+ T cells. Figure 2A demonstrates that placental ET-1 mRNA is elevated in response to RUPP CD4+ T cells in NP recipient rats. Surprisingly, there were no increases in the ET-1 mRNA in neither the renal cortices nor the medulla of NP recipients of RUPP CD4+ T cells. We next utilized our endothelial cell bioassay to determine whether circulating factors were released in response to adoptive transfer of RUPP CD4+ T cells to stimulate vascular ET-1 as has been previously shown in RUPP controls and in preeclamptic women (21, 25, 28). Importantly, we demonstrate in Fig. 3 that over time soluble factors in the serum of NP recipients of RUPP CD4+ T cells stimulates vascular endothelial cells to secrete ET-1 to the same degree as serum from RUPP control placental ischemic rats. These data suggest that the serum from NP recipients of RUPP CD4+ T cells may be less potent or aggressive in activating endothelial cells to secrete ET-1 compared with serum from rats with placental ischemia. Finally, Fig. 4 illustrates the importance of these elevations in ET-1 to mediate the blood pressure response to CD4+ T cells stimulated during placental ischemia. Administration of the ETA receptor antagonist to NP recipient rats significantly blunts hypertension seen in response to RUPP CD4+ T cells. It is important to point out that whereas hypertension in response to adoptive transfer of RUPP CD4+ T cells was blunted in response to the ETA blockade, it did not completely prevent the increase in blood pressure. This suggests that ET-1 activation is not the only mechanism responsible for a rise in blood pressure due to adoptive transfer of RUPP CD4+ T cells. Thus the important findings of the present study are that endothelial cell and local ET-1 activation accompanies CD4+ T cell-induced hypertension in response to placental ischemia during pregnancy.

In previous studies we have shown that administration of TNF-α into NP rats directly simulates endothelial cell ET-1 secretion and stimulates hypertension and tissue ET-1 in pregnant rats (10). In addition TNF-α-induced hypertension is attenuated with an ETA receptor antagonist. We had previously examined the role of endogenous TNF-α to mediate hypertension via ET-1 activation (13). By administering a single injection of Etanercept to RUPP rats, both hypertension and tissue ET-1 were suppressed. Furthermore, we examined endothelial cell activation in the presence of serum from TNF-α-suppressed RUPP rats and serum from RUPP rats with Etanercept exogenously added to the experimental media. In both in vitro studies HUVEC-secreted ET-1 was decreased to levels significantly less than the ET-1 secreted in response to control RUPP serum. In addition, we have shown that one mechanism of sFlt-1-induced hypertension is via upregulation of ET-1 mechanisms and activation of the ETA receptor (17). Importantly, TNF-α and sFlt-1 are significantly upregulated in this model of RUPP CD4+ T cell-induced hypertension (29). The current study, however, did not address the role of TNF-α nor sFlt-1-mediated ET-1 to cause hypertension in response to RUPP CD4+ T cells. This remains, therefore, an important unanswered question in this field of research.

Perspectives and Significance

Although the data presented in this study demonstrate that CD4+ T cells are important in mediating hypertension during pregnancy and that activation of the endothelin system is involved, there are still a number of unanswered questions in this field of investigation. Despite the attenuation of MAP due to antagonism of the ETA receptor in NP + RUPP CD4+ T cells rats, the role of activated T helper 1 cells and specific subsets in mediating impaired renal hemodynamics, proteinuria, or AT1-AA during pregnancy is unclear. It is important to understand the role of endogenous CD4+ T cells to stimulate AT1-AA and/or ET-1 as mechanisms of hypertension in response to placental ischemia. Therefore, important experiments, such as blocking T cell activation or suppressing CD4+ T cells in response to placental ischemia and determining the fate of the adoptively transferred cells are underway in our laboratory and will be necessary to extend our understanding of how these immune mechanisms lead to the pathophysiology associated with preeclampsia.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 1F32HL-108558-01A1, and NIHT32 Grants 1T32HL-105324 1R01HD-067541-01A1, and HL-51971, and by American Heart Association Grant SDG 0835472N.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: K.W., S.R.N., J.H., J.M., and B.L. performed experiments; K.W., S.R.N., J.H., J.M., and B.L. analyzed data; K.W. and B.L. prepared figures; K.W. drafted manuscript; K.W., J.M., J.N.M., M.Y.O., and B.L. approved final version of manuscript; J.N.M., M.Y.O., and B.L. edited and revised manuscript; B.L. conception and design of research; B.L. interpreted results of experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1. Boyman O, Sprent J. The role of interleukin-2 during homeostasis and activation of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 12: 180–190, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Conrad K, Benyo D. Placental cytokines and the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol 37: 240–249, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gee K, Guzzo C, Che Mat N, Ma W, Kumar A. The IL-12 family of cytokines in infection, inflammation and autoimmune disorders. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 8: 40–52, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Granger J. Inflammatory cytokines, vascular function, and hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 286: R989–R990, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Granger J, Alexander B, Bennett W, Khalil R. Pathophysiology of pregnancy-induced hypertension. Am J Hypertens 14: 178S–185S, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Granger J, LaMarca B, Cockrell K, Sedeek M, Balzi C, Chandler D, Bennett W. Reduced uterine perfusion pressure (RUPP) model for studying cardiovascular-renal dysfunction in response to placental ischemia. Methods Mol Med 122: 383–392, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gruslin A, Lemyre B. Pre-eclampsia: fetal assessment and neonatal outcomes. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 25: 491–507, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. LaMarca B, Alexander B, Gilbert J, Ryan M, Sedeek M, Granger J. Pathophysiology of hypertension in response to placental ischemia during pregnancy: a central role for endothelin? Gend Med 5: S133–S138, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. LaMarca B, Brewer J, Wallace K. IL-6 induced pathophysiology during pre-eclampsia: potential therapeutic role for magnesium sulfate? Int J Interferon Cytokine Mediator Res 3: 59–64, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. LaMarca B, Cockrell K, Sullivan E, Bennett W, Granger J. Role of endothelin in mediating tumor necrosis factor-induced hypertension in pregnant rats. Hypertension 46: 82–86, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. LaMarca B, Parrish M, Ray L, Murphy S, Roberts L, Glover P, Wallukat G, Wenzel K, Cockrell K, Martin J, Ryan M, Dechend R. Hypertension in response to autoantibodies to the angiotensin II type I receptor (AT1-AA) in pregnant rats: a role of endothelin-1. Hypertension 54: 905–909, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. LaMarca B, Ryan M, Gilbert J, Murphy S, Granger J. Inflammatory cytokines in the pathophysiology of hypertension during preeclampsia. Curr Hypertens Rep 9: 480–485, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. LaMarca B, Speed J, Fournier L, Babcock S, Berry H, Cockrell K, Granger J. Hypertension in response to chronic reductions in uterine perfusion in pregnant rats: effect of tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade. Hypertension 52: 1161–1167, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. LaMarca B, Wallace K, Granger J. Role of angiotensin II type I receptor agonistic autoantibodies (AT1-AA) in preeclampsia. Curr Opin Pharmacol 11: 175–179, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lamarca B, Wallace K, Herse F, Wallukat G, Martin JJ, Weimer A, Dechend R. Hypertension in response to placental ischemia during pregnancy: role of B lymphocytes. Hypertension 57: 864–871, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lamarca B, Wallukat G, Llinas M, Herse F, Dechend R, Granger J. Autoantibodies to the angiotensin type I receptor in response to placental ischemia and tumor necrosis factor alpha in pregnant rats. Hypertension 52: 1168–1172, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Murphy S, LaMarca B, Cockrell K, Granger J. Role of endothelin in mediating soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 induced hypertension in pregnant rats. Hypertension 55: 394–398, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Noris M, Perico N, Remuzzi G. Mechanisms of disease: pre-eclampsia. Nat Clin Prac Nephrol 1: 98–114, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Parrish M, Murphy S, Rutland S, Wallace K, Wenzel K, Wallukat G, Keiser S, Ray L, Dechend R, Martin J, Granger J, LaMarca B. The effect of immune factors, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and agonistic autoantibodies to the angiotensin II type I receptor on soluble fms-like tyrosine-1 and soluble endoglin production in response to hypertension during pregnancy. Am J Hypertens 23: 911–916, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Parrish M, Ryan M, Glover P, Brewer J, Ray L, Dechend R, Martin JJ, LaMarca B. Angiotensin II type 1 autoantibody induced hypertension during pregnancy is associated with renal endothelial dysfunction. Gend Med 8: 184–188, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roberts J, Edep M, Goldfien A, Taylor R. Sera from preeclamptic women specifically activate human umbilical vein endothelial cells in vitro: morphological and biochemical evidence. Am J Reprod Immunol 27: 101–108, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Roberts J, Lain K. Recent Insights into the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Placenta 23: 359–372, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roberts J, Pearson G, Cutler J, Lindheimer M. Summary of the NHLBI working group on research on hypertension during pregnancy. Hypertension 41: 437–445, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roberts J, Taylor R, Goldfien A. Clinical and biochemical evidence of endothelial cell dysfunction in the pregnancy syndrome preeclampsia. Am J Hypertens 4: 700–708, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roberts L, LaMarca B, Fournier L, Bain J, Cockrell K, Granger J. Enhanced endothelin synthesis by endothelial cells exposed to sera from pregnant rats with decreased uterine perfusion. Hypertension 47: 615–618, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sharma A, Satyam A, Sharma J. Leptin, IL-10 and inflammatory markers (TNF–alpha, IL-6 and IL-8) in preeclamptic, normotensive pregnant and healthy non-pregnant women. Am J Reprod Immunol 58: 21–30, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tam Tam K, George E, Cockrell K, Arany M, Speed J, Martin JJ, Lamarca B, Granger J. Endothelin type A receptor antagonist attenuates placental ischemia-induced hypertension and uterine vascular resistance. Am J Obstet Gynecol 204: e1–e4, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Taylor R, Varma M, Teng N, Roberts J. Women with preeclampsia have higher plasma endothelin levels than women with normal pregnancies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 71: 1675–1677, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wallace K, Richards S, Dhillion P, Weimer A, Edholm E, Bengten E, Wilson M, Martin JJ, Lamarca B. CD4+ T Helper cells stimulated in response to placental ischemia mediate hypertension during pregnancy. Hypertension 57: 949–955, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wallace K, Richards S, Weimer A, Dhillion P, Wallukat G, Wenzel K, Martin JJ, Dechend R, Lamarca B. T Lymphocyte induced AT1-AAs cause hypertension in response to placental ischemia. FASEB J 25: 1030.–1011., 2011 [Google Scholar]