Abstract

Many proteins necessary for sound transduction have been discovered through positional cloning of genes that cause deafness1–3. In this study, we report that mutations of LRTOMT are associated with profound non-syndromic hearing loss at the DFNB63 locus on human chromosome 11q13.3-q13.4. LRTOMT has two alternative reading frames and encodes two different proteins, LRTOMT1 and LRTOMT2, that are detected by Western blot analyses. LRTOMT2 is a putative methyltransferase. During evolution, novel transcripts can arise through partial or complete coalescence of genes4. We provide evidence that in the primate lineage LRTOMT evolved from the fusion of two neighboring ancestral genes, which exist as separate genes (Lrrc51and Tomt) in rodents.

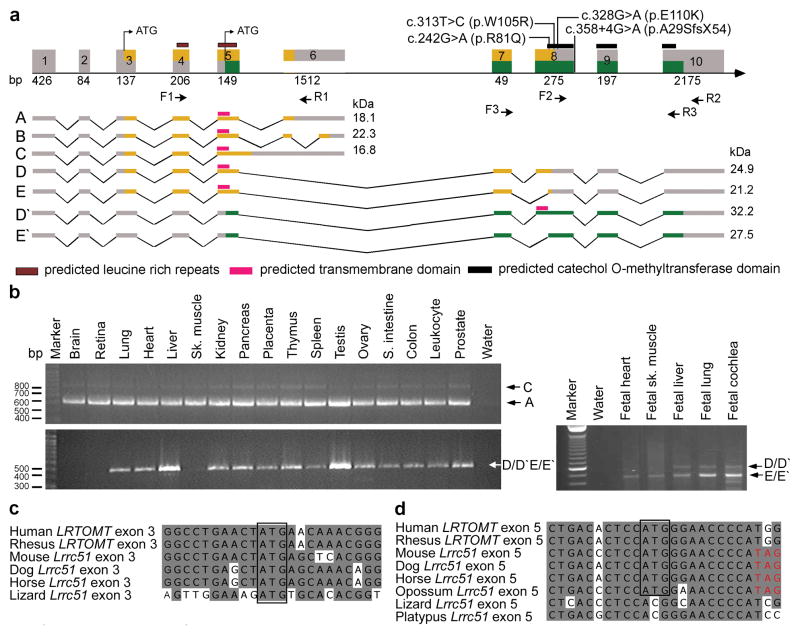

We mapped recessive deafness DFNB63 (OMIM 611451) segregating in eight families to a 2.04 cM interval on human chromosome 11q13.3-q13.4 (refs 5–7). This interval includes FGF3 and mutations of this gene cause a form of syndromic deafness (OMIM 610706) characterized by microtia, microdontia and inner ear agenesis8,9. Three of the eight families were found to co-segregate recessive mutations of FGF3 with all of the features of this syndrome. We used the meiotic recombinations from the five FGF3 mutation-negative families to refine the linkage interval of DFNB63 to 1.03 Mb (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). This interval has 26 annotated and predicted genes (NCBI build 36.1; http://genome.ucsc.org). Using genomic DNA from affected members, we sequenced the protein-coding and non-coding exons and approximately 100 bp flanking each exon of all 26 genes. We discovered four pathogenic mutations in an uncharacterized gene LRRC51, renamed LRTOMT (Fig. 1a and Table 1). Using primers designed to hybridize to LRRC51 exons annotated in build 36.1, we determined the complete exon content of LRTOMT by RT-PCR and 5’ and 3’ RACE analyses using adult human liver cDNA (Supplementary Fig. 2 online). We found a total of 10 exons comprising five different alternatively spliced transcripts of LRTOMT that are widely expressed (Fig. 1a and b). Surprisingly, exons 5, 7 and 8 are included in transcripts encoding two different proteins: LRTOMT1 and LRTOMT2. These exons are predicted to be translated in two alternative reading frames (dual reading frames) and encode either the C-terminus of LRTOMT1 or the N-terminus of LRTOMT2 (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 3 online). When translation of transcript D/D′ starts in exon 3 (Fig. 1c), the encoded protein has two leucine-rich repeats and is named LRTOMT1 (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 4 online). Translation beginning in exon 5 (Fig. 1d) produces LRTOMT2, which is predicted to have a catechol-O-methyltransferase domain. Depending on the use of an alternative acceptor splice site in exon 8, LRTOMT2 can have a predicted transmembrane helix as well (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 5 online). In silico analyses predict that 7% of alternatively spliced human genes have at least one exon that is translated in different reading frames10–14. However, there are few well-studied examples of dual reading frame transcripts of genes in higher organisms13,15.

Figure 1.

LRTOMT has alternative reading frames, and mutations cause nonsyndromic deafness. (a) LRTOMT has ten exons encoding multiple isoforms. Exons 5, 7 and 8 have dual reading frames. The two different reading frames of LRTOMT are colored orange and green. LRTOMT has two predicted translation start-codons, one in exon 3 and the second in exon 5. Grey boxes denote UTRs, and arrows show the location of primer-pairs for expression analyses. Isoforms A to E of LRTOMT1 have one predicted transmembrane domain (TM) and two leucine-rich repeats. Transcripts D′ and E′ are identical in sequence to D and E, respectively, but encode an entirely different protein, LRTOMT2, when translation starts in exon 5 and stops in exon 10. LRTOMT2 isoform D′ has a predicted catechol-O-methyltransferase domain and a TM. (b) PCR analyses of cDNAs from adult and fetal human tissues using primer-pairs shown in panel a. Transcripts A and C are amplified using primers F1 and R1 and are detected in all adult tissues tested. The transcripts D/D′ and E/E′ were detected either using RT-PCR primers F2 and R2 (adult tissues) or primers F3 and R3 (fetal tissues). (c-d) ClustalW alignments of nucleotide sequences of LRTOMT exons 3 and 5 and Lrrc51. Conserved translation start-codons of LRTOMT1 and LRTOMT2 are boxed. (d) If translation begins with the conserved ATG in exon 5 of mouse, dog, horse and opossum, there is an inframe translation stop-codon (TAG, red font).

Table 1.

| Family | Ethnicity | Gene | Mutation (nt) LRTOMT2a | Mutation (aa) LRTOMT2 | Mutation (nt) LRTOMT1a | Mutation (aa) LRTOMT1 | Allele frequencyb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TR57 | Turkish | LRTOMT | c.358+4G>A | p.A29SfsX54 | c.761+4G>A | p.G163VfsX4 | 0/176 |

| FT1A-G | Tunisian | LRTOMT | c.242G>A | p.R81Q | c.645G>A | p.A215A | 0/190 |

| FT2 | Tunisian | LRTOMT | c.313T>C | p.W105R | c.716T>C | 3’ UTR | 0/180 |

| PKDF702 | Pakistani | LRTOMT | c.328G>A | p.E110K | c.731G>A | 3’ UTR | 0/364 |

| PKDF537 | Pakistani | * |

Nucleotide changes are numbered according to the first coding ATG (Accession numbers EU627069, EU627070).

Ethnically matched hearing subjects.

In family PKDF537, no pathogenic mutations were found either in the coding region of FGF3, LRTOMT or in 25 evolutionary conserved regions in the introns of LRTOMT, suggesting that the mutation might be in a nonconserved region of an intron, in a distant regulatory element, or in another gene in the DFNB63 interval. Alternatively, the hearing loss segregating in this large family may have been spuriously linked to chromosome 11q13.3 despite a LOD score of 6.98.

The homozygous mutation (c.358+4G>A) in hearing-impaired individuals of family TR57 alters the splice donor site of exon 8 of LRTOMT (Fig. 1a, Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 6 on line). RT-PCR analysis of LRTOMT revealed that exon 8 was absent in lymphoblastoid RNA transcripts of affected individuals (Supplementary Fig. 6b online). The absence of exon 8 results in a reading frameshift and a premature downstream translation stop codon (p.A29SfsX54) within the mRNA encoding LRTOMT2. Affected individuals of families FT1A-G, FT2 (Supplementary Fig. 1 online) and PKDF702 (ref 6) are homozygous for transition mutations c.242G>A (p.R81Q), c.313T>C (p.W105R), and c.328G>A (p.E110K), respectively (Fig. 1a, Table 1, and Supplementary Fig. 6 online). All three amino acid substitutions in LRTOMT2 are nonconservative16, are predicted to alter the catechol-O-methyltransferase domain of LRTOMT2 (Fig. 1a), and the wild type residues are evolutionarily conserved down to fugu (Supplementary Fig. 5 online). All four mutations of LRTOMT co-segregate with deafness in these families, carriers have normal hearing, and none of the four mutations was detected in ethnically matched normal-hearing subjects (Table 1).

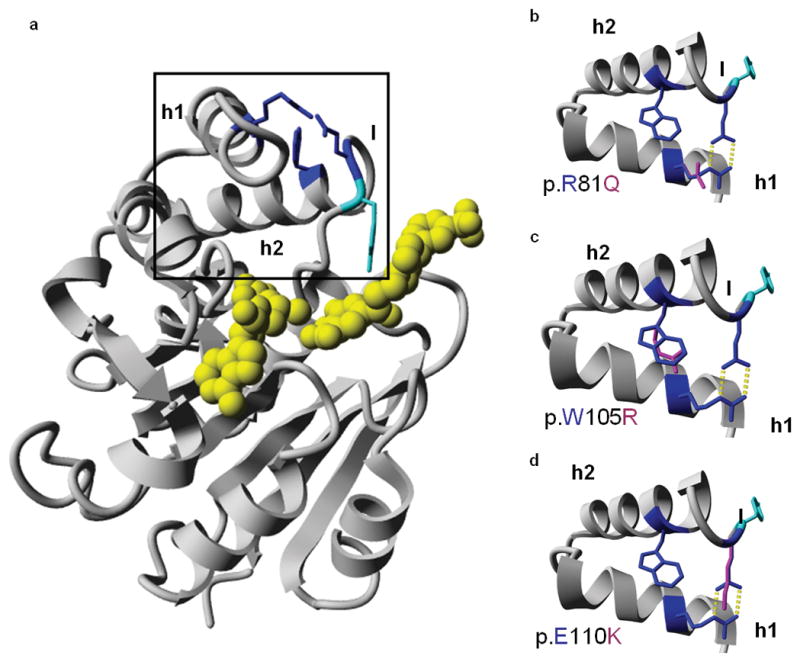

Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT, EC 2.1.1.6) catalyzes the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosyl-L-methionine (AdoMet) to a hydroxyl group of catechols17. The crystal structure of rat COMT (39% identity and 60% similarity to LRTOMT2 for 212 amino acids) was used to model the catechol-O-methyltransferase domain of human LRTOMT2 for prediction of the effect of the missense mutations on this domain (Fig. 2). The three mutated residues are in helix 1 (p.R81Q), in helix 2 (p.W105R), and in the loop that follows helix 2 (p.E110K), and thus not in the hypothetical substrate-binding pockets. However, this loop is predicted to be important for the groove that binds the putative methyl acceptor17. The p.R81 and p.E110 residues are predicted to form a salt bridge and hydrogen bonds between helix 1 and the loop, while p.W105 is predicted to make hydrophobic interactions in the core between the helices (Fig. 2b-d). These residues may therefore be important for protein stability and could indirectly affect the substrate-binding region17.

Figure 2.

Molecular model and predicted effects of missense mutations. (a) Molecular model of the catechol-O-methyltransferase domain of LRTOMT2, residues 79-290. The mutated residues are depicted in blue. The predicted ligands are colored yellow, and the tyrosine residue (p.Y111) that lines the hydrophobic groove of the ligand binding site is shown in cyan. The region enlarged in b-d is boxed. (b-d) Missense mutations of LRTOMT2. The region of helices 1 and 2 and part of the flanking loops is enlarged. Wild type residues p.R81, p.W105 and p.E110 are depicted in blue, mutated residues in pink. Hydrogen bonds are represented by yellow dotted lines. (b) The p.R81 and p.E110 residues form a salt bridge between helix 1 and the loop following helix 2. The p.Q81 residue cannot form this salt bridge as it is not positively charged. Also, the formation of hydrogen bonds is impaired due to the smaller size of glutamine as compared to arginine. (c) The p.W105 residue is predicted to make hydrophobic interactions due to its big side chain. Most of these interactions would be lost by the p.W105R substitution. (d) Mutation p.E110K is predicted to lead to the loss of hydrogen bonds and a salt bridge. There would likely be repulsion between the side chains p.K110 and p.R81 since both are positively charged. h1, helix 1; h2, helix 2; l, loop

Deafness may be due to the predicted destabilizing effects of all four mutations on the catechol-O-methyltransferase domain of LRTOMT2, but we cannot exclude the possibility that it is due to alterations of LRTOMT1 isoforms D and E. While two of the mutations are located in the 3’UTR of mRNA encoding LRTOMT1 isoforms D and E, and a third is predicted to result in a synonymous substitution (p.A215A), all three could affect mRNA stability or regulation in ways that are difficult to predict. The splice site mutation is predicted to cause a frameshift mutation in mRNAs for both LRTOMT2 and LRTOMT1 (Table 1).

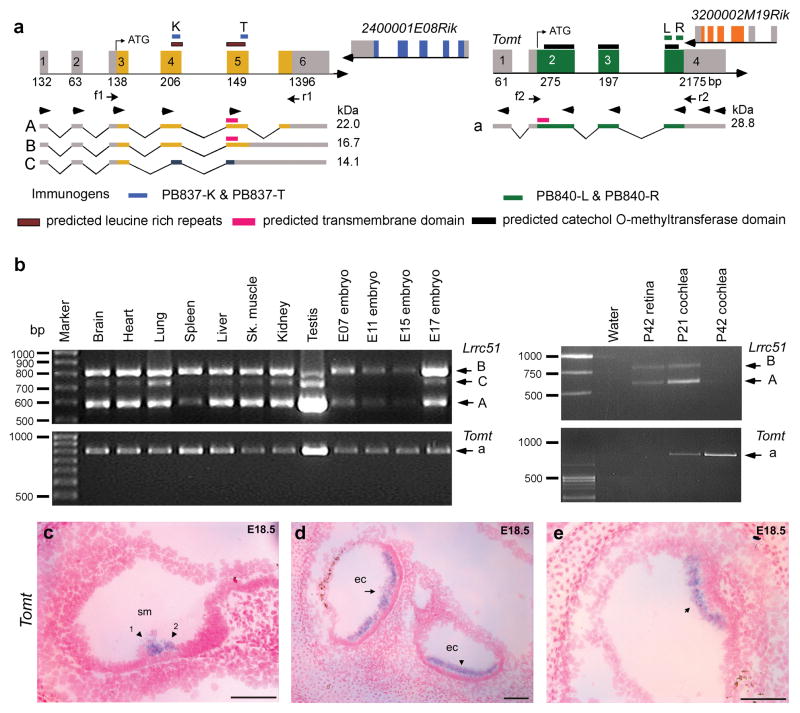

An animal model of LRTOMT would be valuable in evaluating the pathophysiology of these mutations. However, in rodents, there are two separate genes designated Lrrc51 and Tomt (Fig. 3a), which together are orthologous to primate LRTOMT. We were unable to detect fusion transcripts of mouse or rat Lrrc51 and Tomt by RT-PCR analysis of brain, liver and heart cDNA (Fig. 3a) using eight different 5’ and 3’ RACE primers as well as all possible combinations of five forward primers in Lrrc51 and six reverse primers in Tomt (arrowheads, Fig. 3a). LRTOMT fusion transcripts could be readily amplified from human liver and heart cDNAs (Fig. 1a and b).

Figure 3.

Mouse Lrrc51 and Tomt (a) Chromosomal region 7qE3 is syntenic to human chromosome 11q13.3. Unlike humans, mouse has two separate genes, Lrrc51 and Tomt encoding LRRC51 and TOMT, respectively. Translation of Tomt mRNA starts in exon 2. This ATG of LRTOMT is conserved in primates and located in human exon 8 (Supplementary Fig. 2d online). Right pointing arrowheads in exons 1–5 of Lrrc51 indicate forward RT-PCR primers used in all possible combinations with reverse primers (left pointing arrowheads) in Tomt and cDNAs from mouse brain, liver and heart. No mouse fusion transcripts were recovered (data not shown). Arrows (f1, r1 and f2, r2) indicate primer-pairs for expression profiling in b. (b) PCR analyses of Lrrc51 and Tomt transcripts show ubiquitous expression. (c-e) Tomt sense and antisense cRNA probes were hybridized to sagittal sections of whole mouse embryos from embryonic day 12.5 to 18.5. No signal was detected using the control sense probe (data not shown). (c) At E18.5 specific staining is visible in the region of the sensory cells of the cochlea where outer hair cells (arrowhead 1) and inner hair cells (arrowhead 2) are located. (d) At E18.5 in the utricle (arrow) and saccule (arrowhead), a clear signal can be observed in the region of the sensory cells. (e) In E18.5 sensory epithelium of the cristae ampullaris, Tomt mRNA was detected (arrow). No other tissues showed staining for Tomt at E18.5. Scale bars, 100 μm. sm, scala media; ec, endolymph compartment.

Five different primates express transcripts that include nearly all of the exons of LRTOMT as well as a separate transcript equivalent to rodent Lrrc51 (Supplementary Fig. 7 online). Inspection of the mouse genome reveals that, in a hypothetical fusion transcript between Lrrc51 and Tomt, if the first translation start codon (ATG in exon 5) were to be used in rodents, an inframe translation stop codon would be present four codons downstream (Fig. 1d). A fusion protein between LRRC51 and TOMT in rodents is also unlikely because the first exon of Tomt does not have an inframe consensus splice acceptor site (Supplementary Fig. 2c online).

Mouse Lrrc51 has six exons and is predicted to encode LRRC51, a 253 residue protein that has two leucine-rich repeats (Fig. 3a). The four exons of mouse Tomt are predicted to encode TOMT (258 residues), which has one transmembrane helix and a catechol-O-methyltransferase domain (Fig. 3a). An amino acid sequence comparison between mouse LRRC51 and human LRTOMT1 shows 85% identity (93% similarity; Supplementary Fig. 4 online). A comparison between mouse TOMT and isoform D′ (residues 34 to 291) of human LRTOMT2 shows 91% amino acid identity (92% similarity; Supplementary Fig. 5 online). RT- PCR and sequence analyses of cDNAs from mouse embryos and adult tissues showed wide expression of Lrrc51 and Tomt (Fig. 3b).

We next examined embryonic expression of mouse Lrrc51 and Tomt using in situ hybridization. Lrrc51 mRNA is expressed in the developing choroid plexus from embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5) onwards and in the epithelium of the developing airway tract from E14.5 onwards (data not shown), and it is detected in the postnatal inner ear by RT-PCR (Fig. 3b). Tomt expression was not detected anywhere in the embryo at E12.5, while at E14.5 a specific signal is apparent in the developing inner ear. At E16.5, there is expression in the utricle and saccule (data not shown). Detailed images of the cochlear and vestibular epithelia at E18.5 show that Tomt is expressed specifically in the region of the sensory cells of the cochlea, utricle, saccule and crista ampullaris (Fig. 3c–e).

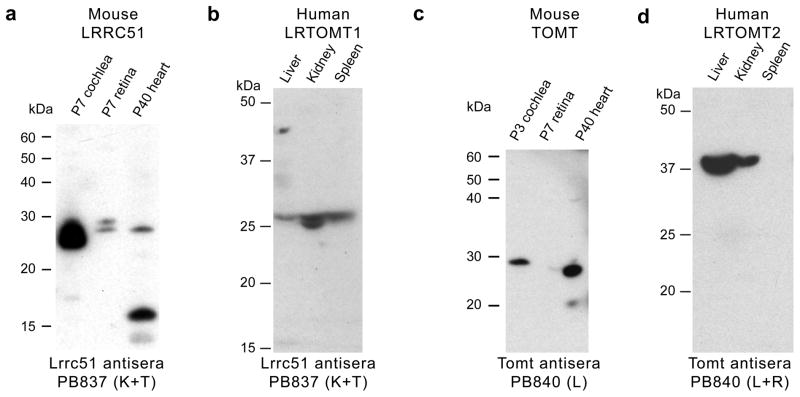

In Western blot analyses of protein extracts from P7 mouse cochlea, retina and P40 heart, antisera against LRRC51 detected two bands (Fig. 4a). Similar size proteins were found for LRTOMT1 in human liver, kidney and spleen (Fig. 4b). Antisera directed against mouse TOMT showed one major band of approximately 28–30 kDa in the cochlea and heart (Fig. 4c), similar to the deduced size of 28.8 kDa from the amino acid sequence of mouse TOMT isoform a (Fig. 3a). Using protein from human liver and kidney, antisera to mouse TOMT recognized a 38 kDa LRTOMT2 (Fig. 4d), which we hypothesize is isoform D′ (32.2 kDa deduced). Taken together, RT-PCR, RACE, and Western blot analyses are consistent with the annotation of mouse Lrrc51 and Tomt as separate genes encoding two different proteins and human LRTOMT as a larger fusion gene with transcripts that are indeed translated in two different reading frames giving rise to LRTOMT1 and LRTOMT2, which have no sequence similarity to one another.

Figure 4.

Western blot analyses of mouse LRRC51 and TOMT, and human LRTOMT1 and LRTOMT2. (a) Western blot analyses using anti-mouse LRRC51, PB837 (K+T) antisera and protein extracts from 7 day old (P7) mouse cochlea and retina (50 μg protein/lane) showed two bands of a size somewhat larger than the predicted sizes for LRRC51 protein isoforms A and B, while in P40 heart, the lower molecular weight isoform was detected along with a ~16 kDa band that might represent isoform C. (b) In human tissue, PB837 (K+T) detected proteins also of a size somewhat larger than predicted for human LRTOMT1 (isoform A, B and C). (c) Western blotting of anti-mouse TOMT (PB840-L) using affinity-purified antisera and mouse cochlear protein extracts (P3; 50 μg/lane) showed one band of about the expected size. In protein extracts from P40 heart, one ~28 kDa band of the expected deduced size (28.8 kDa) was detected. (d) Western blot analysis of protein from human tissues using anti-mouse TOMT antibodies (PB840 L+R) showed a signal in liver and kidney at ~37 kDa, slightly larger than the predicted size of 32.2 kDa for LRTOMT2 (isoform D′).

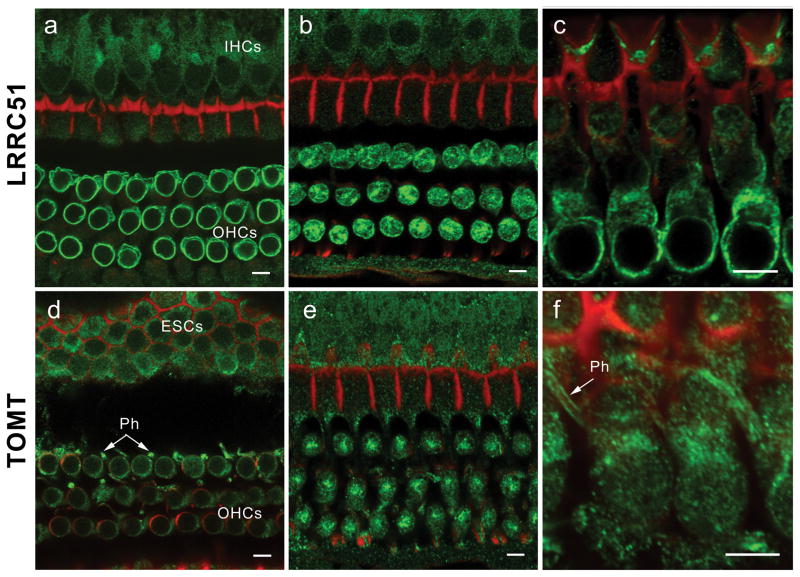

To determine the cellular and subcellular localization of LRRC51 and TOMT, we performed immunofluorescence confocal microscopy on mouse inner ear. LRRC51 immunoreactivity was detected with both antisera PB837-K and PB837-T in the cytoplasm of vestibular hair cells and supporting cells (data not shown) as well as in inner (IHC) and outer hair cells (OHCs) of the organ of Corti (Fig. 5a-c). In OHCs, immunoreactivity of LRRC51 was most prominent along the basolateral wall and distributed throughout the cytoplasm. OHCs have a high density of voltage-sensitive prestin motors in their lateral plasma membranes18,19 that power somatic electromotility20 and a complex cortical lattice connected to the plasma membrane by pillars21–23. LRRC51 may have a special function as a component of the OHC lateral wall.

Figure 5.

Immunolocalization of LRRC51 and TOMT in the P30 mouse inner ear (a) Anti-LRRC51 antiserum PB837 (green) immunostained the basolateral wall of the outer hair cells (OHCs), producing an annular fluorescence pattern in the optical cross-section of whole mount organ of Corti at the level of OHC nuclei. (b) Optical cross-section at the level below the cuticular plate of OHCs. Immunoreactivity to PB837-T antibody is observed at the lateral wall and in the cytoplasm of OHCs with a concentration at the site corresponding to the smooth endoplasmic reticulum. A weaker signal can also be observed in cytoplasm of inner hair cells (IHCs). (c) Longitudinal view of OHC bodies stained with PB837-K antibody highlighting the basolateral wall of OHCs. OHC nuclei are not stained. (d) Confocal images of the optical cross-section of the whole mount organ of Corti at the level of OHC nuclei immunostained with anti-mouse TOMT antibody. Cytoplasmic staining around the nuclei is seen, which is more evident in (e). Immunoreactivity is also observed in the cytoplasm of external sulcus cells (ESCs) and in phalanges (Ph) of outer phalangeal cells. (e) Optical cross-section at the level above the nuclei of OHCs. Immunoreactivity to PB840-L antibody in outer and inner hair cell bodies is concentrated under the cuticular plate of OHCs where smooth endoplasmic reticulum is located. (f) Longitudinal view of OHC bodies showing TOMT concentrated in the cytoplasm of OHCs above the nuclei. An arrow indicates staining of the phalanges (Ph) of outer phalangeal cells. The red signals represent rhodamine-phalloidin staining of F-actin. Scale bars, 5 μm.

TOMT was detected in the cytoplasm of IHCs and OHCs and their supporting cells (Fig. 5d-f) as well as in vestibular hair cells and their supporting cells (data not shown) in adult mouse. In the OHCs of the organ of Corti, TOMT was concentrated under the cuticular plate in a manner similar to LRRC51. TOMT immunoreactivity was also observed in outer phalangeal (Deiters) cells, in particular along the length of plasma membrane of their phalangeal processes. The homology between LRTOMT2 and COMT and the conservation of the majority of the amino acids that are involved in substrate binding17,24 suggest that LRTOMT2 might function as a catechol-O-methyltransferase25. Residual methyltransferase activity in COMT-deficient mice was hypothesized to be derived from an as yet unidentified methyltransferase26, which might be TOMT. Identification of LRTOMT, which encodes both a leucine rich protein and a methyltransferase opens an exciting new field for genetic and physiological studies of the inner ear.

LRTOMT is the first example, to our knowledge, of a human gene that exhibits transcription mediated gene fusion and has dual reading frames, although the latter phenomenon is predicted to be common10, and may have implications for understanding hereditary disorders. In some cases, unrecognized alternative reading frames may account for pleiotropy as well as phenotypic variation among alleles of other genes.

The selective pressures and adaptive benefits, if any, that give rise to a fusion gene such as LRTOMT are yet to be determined. Transcription-induced chimerism of two neighboring genes can generate bifunctional, multi-domain proteins10. An additional benefit may be tight co-expression of functionally related proteins11, which might be true for LRTOMT1 and LRTOMT2, since the mouse orthologs, LRRC51 and TOMT, are both expressed in hair cells. Because Lrrc51 and Tomt are separate transcription units it will be a challenge to model DFNB63 mutations of LRTOMT in the mouse.

METHODS

Subjects and clinical evaluations

Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at the National Center of Excellence in Molecular Biology, Lahore, Pakistan (FWA00001758) and the NIDCD/NINDS at the National Institutes of Health, USA (OH-93-N-016) approved this study. Approval was also obtained from the ethics committees of the medical faculty of the Karadeniz Technical University in Trabzon, Turkey, the Radboud University Nijmegen in The Netherlands and the University Hospital of Sfax in Tunisia. Written informed consent was obtained from all adult participants and from parents of subjects younger than 18 years of age. The Pakistani, Turkish and Tunisian families and some of the clinical data were previously reported5–7. Unpublished Tunisian families segregating nonsyndromic deafness linked to markers on chromosome 11q13.2-q13.3 are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 (online).

Several participating family members underwent otoscopic examination, pure-tone audiometry and vestibular function testing as previously described5–7. MRI or CT-scan analyses were performed to examine inner ear structure of two affected individuals and one normal hearing individual of Pakistani families segregating recessive mutations of FGF3 or LRTOMT.

Genetic Linkage and Mutation Analysis Studies

Protocols for linkage analyses were described previously5–7. All exons and intron-exon boundaries of 26 candidate genes in the refined DFNB63 interval were amplified under standard PCR conditions. Sequences of primers used for the amplification of LRTOMT are given in Supplementary Table 1 (online) and sequence analysis was performed using an ABI 3730 instrument as described earlier27–28. Control DNAs from 88 to 182 normal-hearing Pakistani, Tunisian or Turkish individuals were used to determine mutant allele frequencies (Table 1).

cDNA cloning and sequence analysis

PCR-ready adult human liver cDNA (Ambion) was used for cloning full-length isoforms of LRTOMT. Poly(A)+ RNA was isolated (Poly(A)Pure, Ambion) from postnatal day 1 (P1) to P5 inner ear tissue dissected from 50 C57BL/6J mice and cDNA was synthesized using an oligo-dT primer and PowerScript reverse transcriptase (Clontech). We used premade adult mouse brain, heart, liver and rat brain cDNAs and Marathon-Ready cDNAs (Clontech). For chimpanzee, rhesus, baboon and lemur, the isoforms of LRTOMT were evaluated using cDNAs prepared from total RNA isolated from brain tissue obtained from the Southwest National Primate Research Center and the Duke Lemur Center. Rhesus brain PCR-ready cDNA was also obtained from CytoMol. All PCR products were subcloned and both strands were fully sequenced. The sequences of primers used to PCR amplify cDNA for LRTOMT, Lrrc51, and Tomt from human, chimpanzee, rhesus, baboon, lemur, and rat tissues are provided in Supplementary Table 2 (online).

RT-PCR analysis

Lymphoblast cell lines were established by EBV transformation of peripheral-blood cells from deaf Turkish subjects and control individuals. Total RNA from these cells was isolated using the RNeasy Midi Kit (Qiagen). Subsequently, cDNA synthesis was performed according to standard procedures using random hexamers. PCR reactions were performed with gene-specific primers designed from sequences in exons 7 and 10 (Supplementary Table 2 online). To evaluate splicing of exon 8 of LRTOMT, PCR fragments were isolated from agarose gel and the sequence was verified. For multiple tissue PCR analyses, we used cDNA panels (Clontech) synthesized using the tissues from humans 19 to 69 years old and from mice 8 to 12 weeks old. RNA from human fetal heart, skeletal muscle, liver and lung was obtained from Clontech. cDNA from human fetal cochlear RNA (16 to 22 weeks gestation) was synthesized as described28.

Molecular modeling

The crystal structure of rat COMT was used as a template (pdb-code 1h1d) to build a model of the catechol-O-methyltransferase domain of the human LRTOMT2 (Fig. 2). The WHAT IF-server (http://swift.cmbi.ru.nl) was used for modeling. Energy minimization and analysis were done with Yasara (http://www.yasara.org). For the modeled region (residues 79-290) of LRTOMT2, there is 39% sequence identity with rat COMT. The alignment and a rotating figure of the model is available on http://www.cmbi.ru.nl/~hvensela/catechol.

Digoxigenin cRNA in situ hybridization

Sense and antisense probes for RNA in situ hybridization correspond to the 3’ ends of murine Tomt and Lrrc51. PCR reactions to amplify cDNA were carried out on mouse total brain cDNA using primers given in Supplementary Table 2 (online). Amplimerswere cloned in both orientations into pCR2.1 using the TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen) and sequenced with T7 and M13 primers. Subsequently, PCR reactions were performed with T7 and M13 vector primers using the pCR2.1 constructs as a template.Digoxigenin (DIG)-cRNA probes were generated by using these PCR products, and in situ hybridizations were performed as described previously28. The use of animals was performed under the approval of the animal experiment committee of Utrecht University.

Antibodies, Immunocytochemistry, and Western blot analysis

LRRC51 (PB837-K and PB837-T) and TOMT (PB840-L & PB840-R) antisera were raised in rabbit against the following synthetic peptides (Princeton BioMolecules): KRMGIKPKKVRAKQD (PB837-K), TGLRPVRHSKSGKSLT (PB837-T), IPRLRAQHQLNRADL (PB840-L) and RPRYYLRDLQLLEAHAL (PB840-R) (Genbank accession number pending). Antisera were affinity purified using AminoLink columns (Pierce Biotechnology) with beaded agarose to which we coupled the corresponding synthetic peptide used as the immunogen. A fluorescein-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody was obtained from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech. Specificities of antibodies were determined by Western blot analyses and peptide blocking experiments (Supplementary Fig. 8 online). No signal was detected when the primary antibody was preincubatedfor 2 hr at room temperature with an excess of the immunizingpeptide. Immunocytochemistry was performed as described previously29.

For Western blot analyses, cochlea, retina and heart from C57BL/6J mice (7 and 40 days old) were sonicated in ice-cold protease inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem Biosciences). Protein was extracted by boiling for 5 min in SDS-PAGE sample buffer (0.125M Tris-HCl, 20% glycerol, 4% SDS, 0.005% bromophenol blue). A 50 μg protein sample was separated on a 10% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore) for Western blot analyses as described30. Novex Sharp protein standard cat # LC5800 (Invitrogen) and Precision Plus Protein Prestained Standards Cat# 161-0375 (Bio Rad) were used for mouse and human tissue blots, respectively. For animal experiments approval was obtained by the NINDS/NIDCD Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol 1263-06).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the families for their participation in this study, which was supported by NIDCD/NIH, Intramural Research fund ZO1DC00035-06 and ZO1DC00035-06 to TBF, ZO1DC000060 and ZO1DC000064 to AJG, and funds from the European Commission FP6 Integrated Project EUROHEAR contract number LSHG-CT-20054-512063:2, the Heinsius Houbolt Foundation and by the Karadeniz Technical University Research Fund contract numbers 2002.114.001.3 and 2006.114.001.1. In Tunisia work was also funded by Le Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur, de la Recherche Scientifique et de la Technologie, Tunisia. In Pakistan the Higher Education Commission and the Ministry of Science and Technology in Islamabad, Pakistan supported this project. We thank Barbara Ploplis, Mahmood Ansari, Ayala Lagziel, Erich Boger, Shin-ichiro Kitajiri, Erwin van Wijk, Theo Peters, and Henk Spierenburg for their technical help and Gert Vriend, Frans Cremers, Han Brunner, and Cor Cremers for discussions. We also thank Jonathan Bird, Dennis Drayna, Miriam Meisler, and Susan Sullivan for advice and comments in preparing the manuscript. We thank the Southwest National Primate Research Center, San Antonio, TX for providing brain tissue samples from chimpanzee and baboon, and the Duke Lemur Center, Durham, NC for brain tissue samples from a lemur.

Footnotes

Gene Accession numbers

LRTOMT, GenBank accession numbers EU627066-EU627093

Tomt, GenBank accession number NM_001081679

Lrrc51, GenBank accession number BC025128

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Z.M.A., T.B.F., S.M., E.K., and H.K. conceived and directed the project; Z.M.A. performed linkage, RT-PCR, Westerns and mutational analyses, and cloned isoforms, provided bioinformatic evaluations, prepared figures and co-wrote the manuscript; S.M. enrolled Tunisian families, performed linkage analyses, mutational screening, molecular modeling and helped write the manuscript; E.K. enrolled family TR57 and Turkish controls, performed linkage analysis in family TR57, screened for mutations and did expression profile analysis in human fetal tissues; I.A.B. conducted immunocytochemistry, interpreted results and helped write the manuscript; M.A.M. enrolled Tunisian families and performed genetic linkage and mutational screening; R.W.J.C. performed in situ hybridizations and mutation analysis of candidate genes in the Turkish family; S.R. ascertained Pakistani families, helped with RT-PCR analyses and editing the manuscript; M.H.A. enrolled Tunisian families and performed genetic linkage analyses; H.V. conducted the molecular modeling and helped with the writing; M.N.K. performed mutational analyses; T.A. enrolled Tunisian families and performed genetic linkage analyses; B.V.D.Z. prepared the cRNA in situ hybridization probes and performed hybridizations; S.Y.K. mapped DFNB63 and ascertained Pakistani families; L.A. performed molecular modeling; S.A.R. obtained clinical data for FGF3 and DFNB63 families; R.J.M. evaluated experimental designs and data, and helped write the manuscript; A.J.G. planned clinical evaluation and evaluated the data, and edited the manuscript; I.C. enrolled and examined Tunisian families; R.Ç. performed audiological testing of family TR57; J.O. helped with mutational analyses of TR57; A.K. supervised the work at the Karadeniz Technical University in Trabzon; G.A. directed clinical evaluations in Tunisia; Sh.R. directed all work in Pakistan; T.B.F. directed work at the NIDCD, helped with data interpretation and co-wrote the manuscript; H.A. directed work in Tunisia; H.K. directed work at Radboud University Nijmegen, helped with data interpretation and co-wrote the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Thomas B Friedman, Email: friedman@nidcd.nih.gov, directeur.general@cbs.rnrt.tn.

Hannie Kremer, Email: H.Kremer@antrg.umcn.nl.

References

- 1.Friedman TB, Griffith AJ. Human nonsyndromic sensorineural deafness. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2003;4:341–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.4.070802.110347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant L, Fuchs PA. Auditory transduction in the mouse. Pflugers Arch. 2007;454:793–804. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0253-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morton CC, Nance WE. Newborn hearing screening--a silent revolution. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2151–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasek S, Risler JL, Brezellec P. Gene fusion/fission is a major contributor to evolution of multi-domain bacterial proteins. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1418–23. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalay E, et al. A novel locus for autosomal recessive nonsyndromic hearing impairment, DFNB63, maps to chromosome 11q13.2–q13.4. J Mol Med. 2007;85:397–404. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan SY, et al. Autosomal recessive nonsyndromic deafness locus DFNB63 at chromosome 11q13.2–q13.3. Hum Genet. 2007;120:789–93. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0275-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tlili A, et al. Localization of a novel autosomal recessive non-syndromic hearing impairment locus DFNB63 to chromosome 11q13.3–q13.4. Ann Hum Genet. 2007;71:271–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2006.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gregory-Evans CY, et al. SNP genome scanning localizes oto-dental syndrome to chromosome 11q13 and microdeletions at this locus implicate FGF3 in dental and inner-ear disease and FADD in ocular coloboma. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:3482–93. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tekin M, et al. Homozygous mutations in fibroblast growth factor 3 are associated with a new form of syndromic deafness characterized by inner ear agenesis, microtia, and microdontia. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:338–44. doi: 10.1086/510920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akiva P, et al. Transcription-mediated gene fusion in the human genome. Genome Res. 2006;16 :30–6. doi: 10.1101/gr.4137606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung WY, Wadhawan S, Szklarczyk R, Pond SK, Nekrutenko A. A first look at ARFome: dual-coding genes in mammalian genomes. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e91. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapranov P, Willingham AT, Gingeras TR. Genome-wide transcription and the implications for genomic organization. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:413–23. doi: 10.1038/nrg2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang H, Landweber LF. A genome-wide study of dual coding regions in human alternatively spliced genes. Genome Res. 2006;16:190–6. doi: 10.1101/gr.4246506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parra MK, Tan JS, Mohandas N, Conboy JG. Intrasplicing coordinates alternative first exons with alternative splicing in the protein 4.1R gene. Embo J. 2008;27:122–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quelle DE, Zindy F, Ashmun RA, Sherr CJ. Alternative reading frames of the INK4a tumor suppressor gene encode two unrelated proteins capable of inducing cell cycle arrest. Cell. 1995;83:993–1000. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bordo D, Argos P. Suggestions for "safe" residue substitutions in site-directed mutagenesis. J Mol Biol. 1991;217:721–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90528-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonifacio MJ, et al. Kinetics and crystal structure of catechol-o-methyltransferase complex with co-substrate and a novel inhibitor with potential therapeutic application. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:795–805. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.4.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dallos P, Fakler B. Prestin, a new type of motor protein. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:104–11. doi: 10.1038/nrm730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liberman MC, et al. Prestin is required for electromotility of the outer hair cell and for the cochlear amplifier. Nature. 2002;419:300–4. doi: 10.1038/nature01059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frolenkov GI, Atzori M, Kalinec F, Mammano F, Kachar B. The membrane-based mechanism of cell motility in cochlear outer hair cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1961–8. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.8.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holley MC, Ashmore JF. Spectrin, actin and the structure of the cortical lattice in mammalian cochlear outer hair cells. J Cell Sci. 1990;96 ( Pt 2):283–91. doi: 10.1242/jcs.96.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holley MC, Kalinec F, Kachar B. Structure of the cortical cytoskeleton in mammalian outer hair cells. J Cell Sci. 1992;102 ( Pt 3):569–80. doi: 10.1242/jcs.102.3.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishida Y, Fujimoto T, Takagi A, Honjo I, Ogawa K. Fodrin is a constituent of the cortical lattice in outer hair cells of the guinea pig cochlea: immunocytochemical evidence. Hear Res. 1993;65:274–80. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90220-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lautala P, Ulmanen I, Taskinen J. Molecular mechanisms controlling the rate and specificity of catechol O-methylation by human soluble catechol O-methyltransferase. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:393–402. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.2.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu BT. Catechol-O-Methyltransferase (COMT)-mediated methylation metabolism of endogenous bioactive catechols and modulation by endobiotics and xenobiotics: importance in pathophysiology and pathogenesis. Curr Drug Metab. 2002;3:321–49. doi: 10.2174/1389200023337586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gogos JA, et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase-deficient mice exhibit sexually dimorphic changes in catecholamine levels and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9991–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed ZM, et al. Mutations of the protocadherin gene PCDH15 cause Usher syndrome type 1F. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:25–34. doi: 10.1086/321277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collin RW, et al. Mutations of ESRRB encoding estrogen-related receptor beta cause autosomal-recessive nonsyndromic hearing impairment DFNB35. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:125–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belyantseva IA, et al. Myosin-XVa is required for tip localization of whirlin and differential elongation of hair-cell stereocilia. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:148–56. doi: 10.1038/ncb1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed ZM, et al. PCDH15 is expressed in the neurosensory epithelium of the eye and ear and mutant alleles are responsible for both USH1F and DFNB23. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:3215–23. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.