Abstract

Identifying UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT)-selective probes (substrates that are primarily glucuronidated by a single isoform) is complicated by the enzymes' large overlapping substrate specificity. Here, regioselective glucuronidation of two flavonoids 3,3′,4′-trihydroxyflavone (33′4′THF) and 3,6,4′-trihydroxyflavone (364′THF) is used to probe the activities of hepatic UGT1A1. The glucuronidation kinetics of 33′4′THF and 364′THF was determined using 12 recombinant human UGT isoforms and pooled human liver microsomes (pHLM). The individual contribution of main UGT isoforms to the metabolism of the two flavonoids in pHLM was estimated using the relative activity factor approach. UGT1A1 activity correlation analyses using flavonoids-4′-O-glucuronidation vs. β-estradiol-3-glucuronidation (a well-recognized marker for UGT1A1) or vs. SN-38 glucuronidation were performed using a bank of HLMs (n=12) including three UGT1A1-genotyped HLMs (i.e., UGT1A1*1*1, UGT1A1*1*28 and UGT1A1*28*28). The results showed that UGT1A1 and 1A9, followed by 1A7, were the main isoforms for glucuronidating the two flavonoids, where UGT1A1 accounted for 92 ± 7 % and 91 ± 10 % of 4′-O-glucuronidation of 33′4′THF and 364′THF, respectively, and UGT1A9 accounted for most of the 3-O-glucuronidation. Highly significant correlations (R2 > 0.944, p < 0.0001) between the rates of flavonoids 4′-O-glucuronidation and that of estradiol-3-glucuronidation or SN-38 glucuronidation were observed across 12 HLMs. In conclusion, UGT1A1-mediated 4′-O-glucuronidation of 33′4′THF and 364′THF were highly correlated with glucuronidation of estradiol (3-OH) and SN-38. This study demonstrated for the first time that regioselective glucuronidation of flavonoids can be applied to probe hepatic UGT1A1 activity in vitro.

Keywords: Probe substrate, Flavonoids, UGTs, SN-38, Regioselectivity

Introduction

UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs)-mediated glucuronidation is a major phase II metabolic pathway that facilitates efficient elimination and detoxification of structurally diverse groups of xenobiotics (e.g., SN-38 and nitrosamines) and endogenous compounds (e.g., bilirubin and estradiol). UGT genetic deficiency and polymorphisms are associated with inherited physiological disorders, whereas inhibition of glucuronidation by the concomitant use of certain drugs is related to drug induced toxicities.1-3 On the other hand, extensive glucuronidation can be a barrier to oral bioavailability as rapid and extensive first-pass glucuronidation (or premature clearance by UGTs) of orally administered agents usually results in the poor oral bioavailability and/or lack of efficacies. 3,4

Human UGTs are classified into four families: UGT1, UGT2, UGT3, and UGT8.5 The most important drug-conjugating UGTs belong to UGT1 and UGT2 families. At present, 16 human UGT isoforms from UGT1A (9 members) and UGT2B (7 members) subfamilies are identified: 5 namely, UGT1A1, 1A3, 1A4, 1A5, 1A6, 1A7, 1A8, 1A9, 1A10, 2B4, 2B7, 2B10, 2B11, 2B15, 2B17 and 2B28. Their distribution (probed by mRNA level) in major metabolizing organs, as well as other organs/tissues were well studied.6,7 Compared to UGT1As, UGT2Bs are much more abundantly expressed in human liver. UGT2B4 has the highest expression, followed by UGT2B15. Among the UGT1A isoforms, UGT1A1, 1A4, 1A6 and 1A9 have moderate expression in the liver. 6

Within the 9 UGT1A isoforms, UGT1A1 is perhaps the most significant one for maintaining human health. Its genetic deficiency may impair the metabolism of bilirubin, resulting in severe hyperbilirubinemia disorders such as Crigler-Najjar Syndrome and Gilbert's syndrome.1, 8, 9 Moreover, UGT1A1 is mainly responsible for SN-38 clearance.10 SN-38 is the active metabolite of irinotecan (CPT-11), a widely used anticancer drug, especially for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Generic polymorphisms in UGT1A1 (e.g., UGT1A1*28 variant with low UGT1A1 expression) has been linked to irinotecan toxicity.11 The frequency of UGT1A1*28 allele (promoter (TA)6/7TAA mutation) varies by ethnic and racial origin, and is ∼10% in a white population.12 This high penetration rates necessitate the UGT1A1 genotyping of patients prior to the irinotecan treatment, a protocol recommended by the FDA. 11

Flavonoids are a class of natural polyphenols, consumption of which is linked to numerous health benefits such as antioxidant and anticancer.13 It is well-known that flavonoids are subjected to extensive glucuronidation, resulting in poor oral bioavailabilities.14,15 Although UGT1A isoforms showed vast overlapping substrate specificities (as evaluated by counting all metabolites), 16 - 19 regioselective glucuronidation of multi-hydroxyl flavonoids has been demonstrated to be highly isoform-dependent for many flavonoids.3 In the study of quercetin glucuronidation, 20 UGT1A3's highest glucuronidation preferred 3′-O-glucuronide, whereas UGT1A9 favored 3-O-glucuronidation.

Regioselectivity refers to the preference for formation of one glucuronide isomer over another, when a substrate possesses more than one possible glucuronidation site. Regioselectivity of various UGTs has been examined for a number of compounds such as estradiol, estrone, morphine and resveratrol. 21-23 Elucidation of UGTs regioselectivity would facilitate the understanding of UGT-substrates interaction with respect to binding property.24 In addition, typical generation of a particular glucuronide isomer from a substrate was used to probe UGT activity in human tissues in vitro. For example, β-estradiol 3-glucuronidation is considered an excellent marker of UGT1A1 activity, 25,26 and morphine 6-glucuronidation may be used as a selective probe for UGT2B7 activity.27

As stated by Court 25 and Miners et al.28, UGT-selective probes have many significant applications in the study of drug glucuronidation. For example, they can be used to (1) identify a specific functional UGT in human tissues; (2) predict possible UGT-mediated drug-drug interactions; and (3) elucidate the functional significance of genetic polymorphisms. In this paper, we characterized two flavonoids (3,3′,4′-trihydroxyflavone and 3,6,4′-trihydroxyflavone) as the UGT1A1 probes based on initial screening (i.e., selectivity evaluation by phenotyping each compound with a panel of recombinant UGT isoforms) of ∼ 67 flavonoid compounds derived from 5 subclasses (flavone, isoflavones, flavonone, chalcone and flavonols) (published and unpublished data). 16-19,24,29,30 The individual contributions of UGT1A1 and/or 1A9 to metabolism of the two flavonoids and SN38 in pooled human liver microsomes were estimated using enzyme kinetic experiments combined with the relative activity factor (RAF). The selectivity of UGT1A1 towards the flavonoids, estradiol and SN-38 were further evaluated in a bank of 12 HLMs based on activity correlation analysis.

Experimental Section

Materials

Twelve recombinant human UGT isoforms (Supersomes™, i.e., UGT1A1, 1A3, 1A4, 1A6, 1A7, 1A8, 1A9, 1A10, 2B4, 2B7, 2B15 and 2B17), pooled human liver microsomes (from 50 donors), 3 UGT1A1 genotyped human liver microsomes (i.e., UGT1A1*1*1 (Wild-type), UGT1A1*1*28 (allelic variant) and UGT1A1*28*28 (allelic variant), and rabbit anti-human UGT1A1 polyclonal antibody were purchased from BD Biosciences (Woburn, MA). A bank of individual human liver microsomes with diverse UGTs activities (n=8, designated as HLM-1, HLM-2,…, HLM-8 ) was purchased from Xenotech (Lenexa, KS). Rabbit anti-goat IgG-HRP was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Two flavonoids (see Fig.1 for chemical structures) (i.e., 3,3′,4′-trihydroxyflavone (33′4′THF), and 3,6,4′-trihydroxyflavone (364′THF)) were purchased from Indofine Chemicals (Somerville, NJ). 17β-estradiol (also referred as estradiol in this paper, see Fig.4 for chemical structure), β-estradiol-3-glucuronide, 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin (SN-38, see Fig.4 for chemical structure), SN-38-glucuronide, propofol, and propofol-glucuronide were obtained from Toronto Research Chemicals (North York, Ontario, Canada). Uridine diphosphoglucuronic acid (UDPGA), alamethicin, D-saccharic-1,4-lactone monohydrate, and magnesium chloride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Ammonium acetate was purchased from J.T. Baker (Phillipsburg, NT). All other materials (typically analytical grade or better) were used as received.

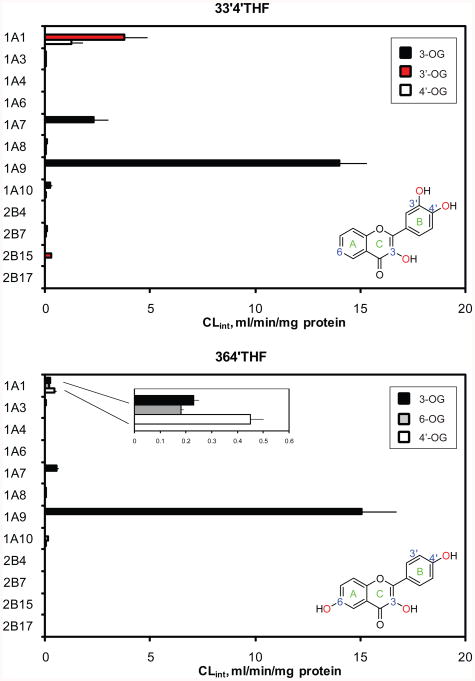

Figure.1.

Phenotyping of 33′4′THF (top) and 364′THF (bottom) using 12 recombinant UGTs, showing UGT1A1, 1A7 and 1A9 were the main isoforms glucuronidating both flavonoids. Intrinsic clearances (CLint = Vmax/Km) were obtained from kinetic determination. OG: O-glucuronide. Insets show corresponding chemical structures for each flavonoid probe.

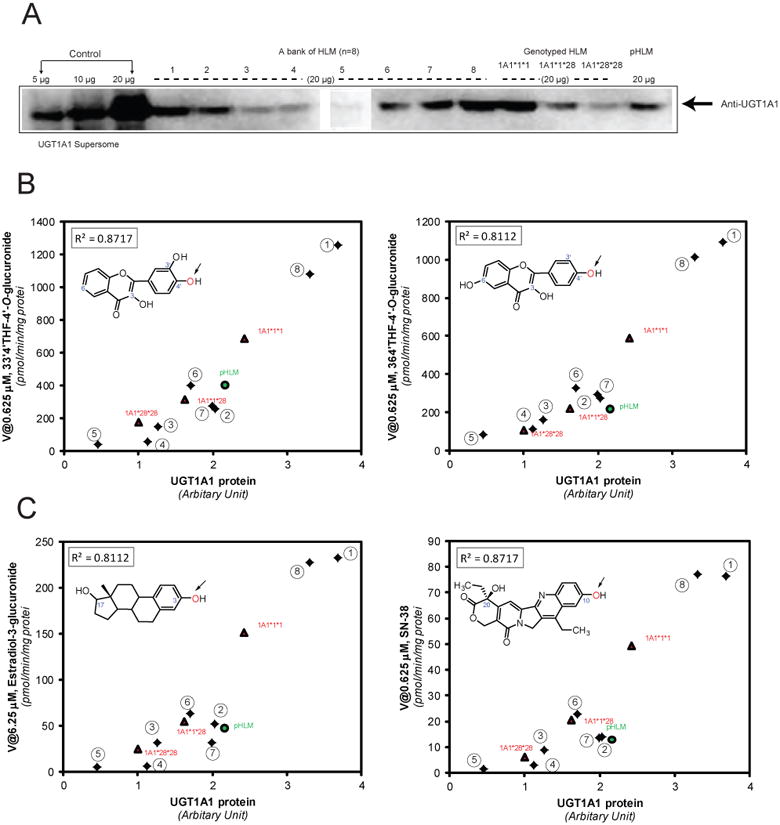

Figure.4.

Western blots of recombinant UGT1A1 and human liver microsomes (Panel A). Panels B-C: the correlation analyses (n=12) were performed between the UGT1A1 protein and 33′4′THF glucuronidation (4′-OH) (B, left), 364′THF glucuronidation (4′-OH) (B, right), estradiol glucuronidation (3-OH) (C, left), and SN-38 glucuronidation (C, right). The 8 individual HLMs from XenoTech were indicated in numbers. R2: Pearson correlation coefficient. In panel B-C, insets show corresponding chemical structures for each UGT1A1 substrate. The arrows indicate the sites of glucuronidation.

Immunoblotting

The recombinant UGT1A1 and human liver microsomes were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (10% acrylamide gels) and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Blots were probed with anti-UGT1A1 antibody (BD Biosciences, Woburn, MA), followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Membranes were analyzed on a FluorChem FC Imaging System (Alpha Innotech), and intensities of UGT bands were measured by densitometry using the AlphaEase software.

Glucuronidation Assay and Kinetics

The experimental procedures of glucuronidation assays were exactly the same as our previous publications.24,29,30 Glucuronide(s) formation was verified to be linear with respect to incubation time (5-60 min) and protein concentration (13-53 μg/ml). Glucuronidation rates were calculated as nmol glucuronide(s) formed per reaction time per protein amount (or nmol/min/mg protein), as the actual enzyme concentration is unknown. Enzyme kinetics parameters for glucuronidation were determined by measuring initial reaction rates at a series of substrate concentrations. All experiments were performed in triplicates.

UPLC analysis

The Waters ACQUITY™ UPLC (Ultra performance liquid chromatography) system was used to analyze a parent compound (or aglycone) and its respective glucuronide(s). Details of the analytical conditions are given in Table S1 (Supporting Information). The quantitation of estradiol-3-glucuronide, propofol glucuronide and SN-38 glucuronide was made with the authentic reference standards. While quantitation of the flavonoid glucuronides was based on the standard curve of the parent compound and further calibrated with the conversion factor (Table S1) using the same method that we have published earlier.24,29,30 Representative chromatograms and UV spectra were shown in Fig.S1 (Supporting Information).

Identification of the Structure of Flavonoid Glucuronide

Glucuronide structures were identified using 3 independent methods in a sequential process as summarized in our earlier publication.24,29-31 First, the glucuronides were hydrolyzed by β-D-glucuronidase to the aglycones. Second, the glucuronides were identified as mono-glucuronides which showed mass of (aglycone's mass+176) Da using UPLC/MS/MS. 176 Da is the mass of a single attached glucuronic acid.

Finally, the sites of glucuronidation were confirmed by the “UV spectrum maxima (λmax) shift method”.29-31 Substitution of 3-hydroxyl group led to a hypsochromic shift (i.e. to shorter wavelength) in band I (300∼380nm), the shift was in the order of 13 ∼ 30 nm, whereas glucuronidation of 4′-hydroxyl group produced a 5 ∼ 10 nm shift. In contrast, substitution of the hydroxyl group at position C6 or C3′ had minimal or no effect on the λmax of the UV spectrum (Table S2 & Fig.S1, Supporting Information).

Data analysis

Kinetic parameters were estimated by fitting the proper models (Michaelis-Menten, substrate inhibition or Hill equations) to the substrate concentrations and initial rates with a weighting of 1/y. Similar to glucuronidation rates, Vmax values were also determined as nmol glucuronide formed/min/mg Supersomes protein (or nmol/mg protein/min). Eadie-Hofstee plots were used as diagnostics for model selection. Data analysis was performed by Graph Pad Prism V5 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The goodness of fit was evaluated on the basis of R2 values, RSS (residual sum of squares), RMS (root mean square) and residual plots.

Maximal clearances (CLmax) were estimated using eq. 1,32,33 where Vmax is the maximal velocity rate, S50 is the substrate concentration resulting in 50% of Vmax, and n is the Hill coefficient:

| (eq.1) |

Correlation (Pearson) analysis was performed by GraphPad Prism V5 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

UGT1A1 and 1A9 Relative Activity Factor Determination

The relative activity factor (RAF) approach was used for scaling UGT activities obtained using cDNA-expressed enzymes to HLM. 34 RAFs (eq.2) here were defined as the HLM/recombinant enzyme activity (e.g., CLint, intrinsic clearance) ratio of a particular isoform toward a probe substrate.34

| (eq.2) |

The relative amount of specific substrate metabolism attributed to an individual UGT enzyme was estimated by multiplying glucuronidation parameters (i.e., CLint) observed with this enzyme by the corresponding RAF. In this study, we calculated RAFs for UGT1A1 and UGT1A9 using selective probe substrates for UGT1A1 and 1A9 (1A1: estradiol, 3-glucuronide; 1A9: propofol). Estradiol 3-glucuronidation is an excellent marker for UGT1A1, showing a good correlation with bilirubin glucuronidation.35 Propofol is considered as an appropriate probe substrate for UGT1A9 in human liver, insomuch as a concentration of ≤ 100 μM (lower than Km value) is used for activity measurement, because of the potential to be glucuronidated by other UGT isoforms. 25

Results

UGT Isoforms Involved in 33′4′THF and 364′THF Glucuronidation

As shown in Fig. 1, UGT1A1, 1A7 and 1A9 were the main isoforms glucuronidating both flavonoids. UGT1A9 showed the highest activities, followed by UGT1A1 and 1A7. In terms of the number of glucuronides formed, UGT1A7 and 1A9 only generated a single 3-O-glucuronide, demonstrating a strict 3-OH regioselectivity. By contrast, multiple glucuronide isomers were formed by UGT1A1 (two for 33′4′THF: 3′-O- and 4′-O-glucuronide; three for 364′THF: 3-O-, 6-O-, and 4′-O-glucuronide). UGT1A7 was not considered in further studies, because it expresses only in extrahepatic tissues (i.e., stomach or esophagus).6 We also determined the relative expression level between the 8 UGT1A isoforms by Western blot analysis using anti-UGT1A antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), as described previously.29,33 There was only <1.3-fold variability in the apparent expression of the UGT1A isoforms (Fig.S2, Supporting Information). Thus the UGT1A activity was not normalized using the relative expression. 33 It is acknowledged though that the inter-enzyme activity comparison between UGT1As and UGT2Bs might be affected by the actual enzyme levels which could not be determined due to the lack of a specific antibody for the majority of human UGT isoforms.

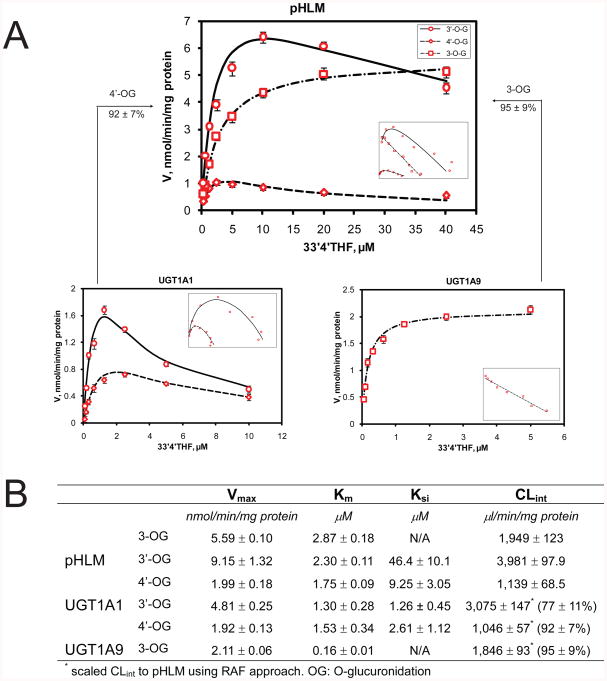

Contribution of UGT1A1 and 1A9 to Metabolism of 33′4′THF in pHLM

Glucuronidation kinetic profiles and constants derived from incubation of 33′4′THF with pHLM, UGT1A1 and UGT1A9 were shown in Fig.2. The intrinsic clearance (CLint) obtained with recombinant UGT1A1 and UGT1A9 were scaled to pHLM using the RAFs calculated from the UGT1A1-mediated 3-glucuronidation of estradiol (RAF = 0.83, Fig.S3A) and UGT1A9-mediated glucuronidation of propofol (RAF = 0.14, Fig. S3B). As can be seen in Fig.2, the scaled CLint of UGT1A1 and UGT1A9 represented 92 ± 7% (4′-O-glucuronidation) and 95 ± 9% (3-O-glucuronidation) of the CLint values in pHLM, respectively. In addition, UGT1A1 contributed a less percentage (77%) of 3′-O-glucuronidation in pHLM. The residual (approximately 23%) 3-O-glucuronide production in pHLM might be attributable to UGT2B15, which is second most abundant in human liver 6 and showed some 3-O-glucuronidation activity (Fig.1).

Figure.2.

Kinetic profiles (panel A) and parameters (panel B) of glucuronidation derived from incubation of 3,3′,4′-trihydroxyflavone (33′4′THF) with pooled human liver microsomes (pHLM), recombinant UGT1A1 and UGT1A9. Insets show corresponding Eadie-Hofstee plots for each kinetic profile. Circles and solid lines denote observed and predicted formation rates of flavonoid 3′-O-glucuronides, respectively; diamonds and dashed lines denote observed and predicted formation rates of flavonoid 4′-O-glucuronides, respectively; squares and dash-dotted lines denote observed and predicted formation rates of flavonoid 3-O-glucuronides, respectively. Predicted rates were from Michaelis-Menten or substrate inhibition models. Each data point represents the average of three replicates. Experimental details are presented under Experimental Section.

Contribution of UGT1A1 and 1A9 to metabolism of 364′THF in pHLM

Glucuronidation kinetic profiles and constants derived from incubation of 364′THF with pHLM, UGT1A1 and UGT1A9 were shown in Fig.3. The scaled CLint values of UGT1A1 and UGT1A9 accounted for 91 ± 10% (4′-O-glucuronidation) and 94 ± 7% (3-O-glucuronidation) of the CLint values in pHLM, respectively. Although 3-O-glucuronide was primarily generated by UGT1A9, a minor contribution (9%) from UGT1A1 was also observed. For 6-O-glucuronide formation, a large portion (68%) was attributed to UGT1A1. However, it remains to be identified as to the other contributor(s) responsible for the remaining 32% of 6-O-glucuronide formation.

Figure.3.

Kinetic profiles (panel A) and parameters (panel B) of glucuronidation derived from incubation of 3,6,4′-trihydroxyflavone (364′THF) with pooled human liver microsomes (pHLM), recombinant UGT1A1 and UGT1A9. Insets show corresponding Eadie-Hofstee plots for each kinetic profile. Diamonds and dashed lines denote observed and predicted formation rates of flavonoid 4′-O-glucuronides, respectively; triangle and dotted lines denote observed and predicted formation rates of flavonoid 6-O-glucuronides, respectively; squares and dash-dotted lines denote observed and predicted formation rates of flavonoid 3-O-glucuronides, respectively. Predicted rates were from Michaelis-Menten or substrate inhibition models. Each data point represents the average of three replicates. Experimental details are presented under Experimental Section.

Expression-activity correlation of UGT1A1 in Human Livers

The expression levels of UGT1A1 in 12 human liver microsomes were determined by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4A). In the product datasheet, it is described that the UGT1A1 antibody does not cross-react with UGT1A4, UGT1A6, UGT1A9, UGT1A10, and UGT2B15, which was also confirmed by Izukawa et al.7 We verified that the UGT1A1 antibody did not have co-reactivity with UGT1A9 (data not shown). The variability of UGT1A1 protein in HLMs was 8.2-fold (Fig.4). The UGT1A1 protein levels were significantly correlated with the UGT1A1 activities probed with 4′-O-glucuronidation of 33′4′THF and 364′THF (R2 > 0.811; p < 0.0001) (Fig.4B). Substantial correlations between the UGT1A1 protein and UGT1A1-mediated estradiol (3-OH) glucuronidation and SN-38 glucuronidation were also observed (R2 > 0.811; p < 0.0001) (Fig.4C).

UGT1A1 Activity correlation analysis

We chose estradiol and SN-38 glucuronidation rates for correlation analysis because estradiol is the most important female hormone, and also a prototypical substrate of human UGT1A1. In contrast, SN-38 is the active moiety for the widely used anticancer drug irinotecan, and UGT1A1 activities are inversely correlated to its intestinal toxicities.11

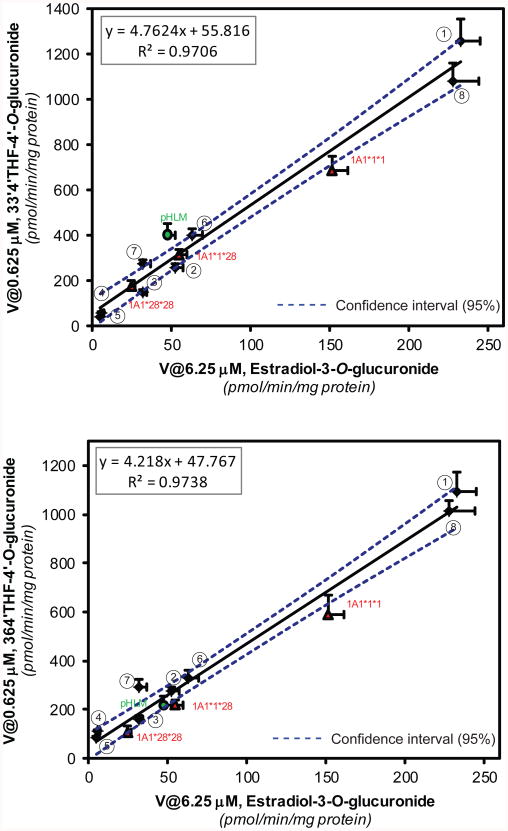

Highly significant correlations (R2 ≥ 0.970, p<0.0001) were observed between rates of estradiol-3-O-glucuronidation and rates of 4′-O-glucuronidation of 33′4′THF or 364′THF measured in a panel of HLMs (n=12) (Fig.5 and/or Table 1). Please note that the activity correlation here was made between reaction rates measured at substrate concentrations that were lower than or near Km (S50 for estradiol) values (for pHLM-mediated glucuronidation), which best approximate the intrinsic activity of a specific UGT isoform in HLMs.36

Figure.5.

UGT1A1 activity correlation (R2: Pearson correlation coefficient) between flavonoid-4′-O-glucuronidation (top: 33′4′THF; bottom: 364′THF) and estradiol-3-glucuronidation in a bank of HLMs (n=12). The 8 individual HLMs from XenoTech were indicated in numbers. The borders of the 95% confidence intervals were plotted as dashed lines.

Table.1.

Pearson correlation coefficients (R2) of glucuronidation reactions between 33′4′THF (4′-OH), 364′THF (4′-OH), estradiol (3-OH) and SN-38 in the bank of 12 HLMs. The confidence of these correlations was associated with a p value of < 0.0001.

| 33′4′THF V@ 0.625 μM | 33′4′THF V@ 1.25 μM | 33′4′THF V@2.5 μM | 364′THF V@0.625 μM | 364′THF V@1.25 μM | Estradiol V@6.25μM | Estradiol V@1.25μM | SN-38 V@0.625 μM | SN-38 V@1.25μM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33′4′THF V@1.25μM | 0.9903 | ||||||||

| 33′4′THF V@2.5μM | 0.9733 | 0.9866 | |||||||

| 364′THF V@0.625 μM | 0.9687 | 0.9796 | 0.9950 | ||||||

| 364′THF V@1.25μM | 0.8767# | 0.9145 | 0.9471 | 0.9535 | |||||

| Estradiol V@6.25μM | 0.9706* | 0.9743 | 0.9788 | 0.9738* | 0.9021 | ||||

| Estradiol V@1.25 μM | 0.9478 | 0.9506 | 0.9602 | 0.9582 | 0.8967 | 0.9926 | |||

| SN-38 V@0.625 μM | 0.9657* | 0.9687 | 0.9739 | 0.9775* | 0.9174 | 0.9936 | 0.9893 | ||

| SN-38 V@1.25 μM | 0.9687 | 0.9718 | 0.9789 | 0.9849 | 0.9224 | 0.9917 | 0.9862 | 0.9978 | |

| SN-38 V@2.5 μM | 0.9779 | 0.9820 | 0.9879 | 0.9892 | 0.9290 | 0.9907 | 0.9785 | 0.9953 | 0.9957 |

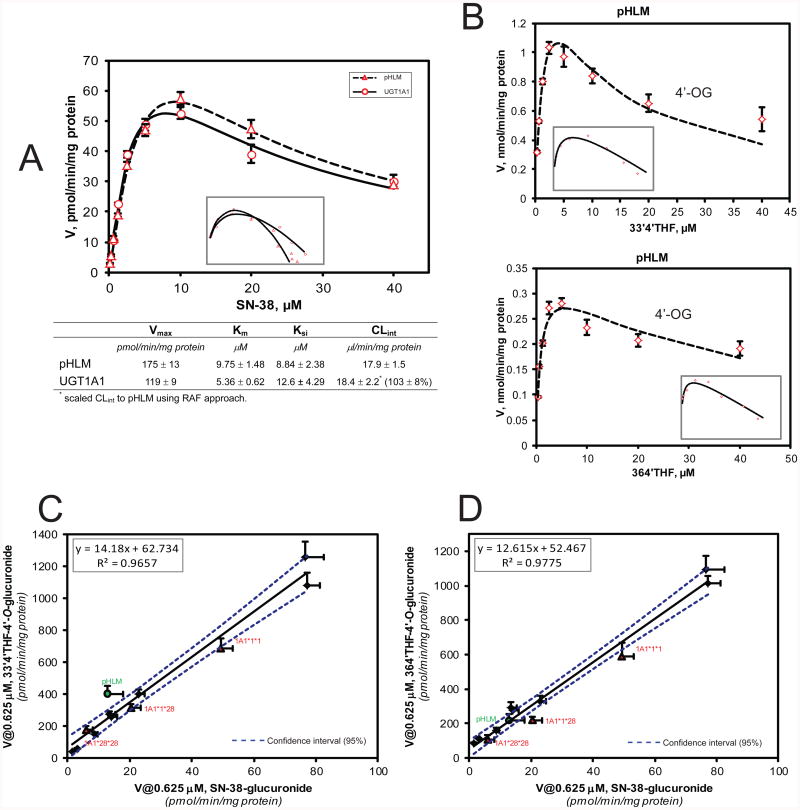

Glucuronidation of SN-38 in pHLM appeared to be fully (103 ± 8%) correlated with UGT1A1 activities (Fig.6A), based on the RAF approach. As expected, rates of SN-38 glucuronidation was highly correlated (R2 > 0.965, p < 0.0001) with rates of 4′-O-glucuronidation of 33′4′THF or 364′THF in the same 12 HLMs bank (Fig.6C/D and Table 1). Additionally, similar pattern of kinetic profile (substrate inhibition) was observed between 4′-O-glucuronidation of 33′4′THF or 364′THF and SN-38 glucuronidation (Fig.6B). To rule out the possibility that the observed correlations between the flavonoids and known UGT1A1 probes were due to the differences in the quality of the liver microsomes, we demonstrated that there was a lack of correlation (p > 0.5) between the flavonoid-4′-O-glucuronidation and testosterone-O-glucuronidation (a UGT2Bs probe 37 in the same set of 12 HLMs (Fig.S4, Supporting Information). Lastly, we confirmed that recombinant UGT1A9 had no measurable activity towards SN-38 at lower concentrations (0.625-5 μM), and limited activity (10 ± 0.8 pmol/min/mg protein, ∼5-folds less than that of UGT1A1) at a higher concentration of 10 μM, somewhat similar to the early observation.38 Considering the fact that the in vivo concentration of SN-38 is quite low (< 0.1 μM) after a standard therapy,39 we believe that UGT1A9's contribution to SN-38 glucuronidation is likely to be quite limited.

Figure.6.

Panel A: Kinetic profiles (top) and parameters (bottom) of glucuronidation derived from incubation of SN-38 with pooled human liver microsomes (pHLM) and recombinant UGT1A1. Panel B: Kinetic profile of 33′4′THF-4′-O-glucuronidation (top) and 364′THF-4′-O-glucuronidation (bottom) mediated by pHLM. Similar pattern of kinetic profile (substrate inhibition) was observed between flavonoids 4′-O-glucuronidation and that of SN-38 glucuronidation. Panel C/D: UGT1A1 activity correlation (R2: Pearson correlation coefficient) between flavonioid-4′-O-glucuronidation (C: 33′4′THF; D: 364′THF) and SN-38 glucuronidation in a bank of HLMs (n=12). The borders of the 95% confidence intervals were plotted as dashed lines. In Panels A-B, insets show corresponding Eadie-Hofstee plots for each kinetic profile.

Discussion

We have shown that 33′4′THF and 364′THF may be used as probe substrates for UGT1A1 because UGT1A1 displayed high degree of selectivity toward their 4′-O-glucuronidation, and rates of their 4′-O-glucuronidation are highly correlated with UGT1A1 expression and activities in human liver microsomes. The evidence is strong and includes four sets of independent results: (1) the probes were predominantly glucuronidated (at 4′-OH) by UGT1A1 based on phenotyping of commercially available recombinant UGTs; (2) metabolism (at 4′-OH) of the probes in human liver microsomes was mainly contributed by the targeted UGT isoform; (3) the selectivity of UGT1A1 towards the flavonoid probes (4′-O-glucuronidation) were comparable to the known selective substrates (estradiol and SN-38) derived from activity correlation analysis; and (4) The polymorphic variants (UGT1A1*28) with decreased UGT1A1 protein expression showed markedly lower UGT1A1 activity towards the probes. Therefore, the interference of other untested hepatic isoforms (e.g., UGT2B10) on the use of the two probes was presumed to be negligible, which was supported in part by the poor correlation between 4′-O-glucuronidation of these 2 flavonoids and that of testosterone, an important substrate of UGT2Bs.

Utilities of UGT-selective probes are multifaceted in the area of glucuronidation during the drug development process. 25,28 Firstly, they can be used to substantiate the identification of specific UGTs involved in glucuronidation of drug candidates in human tissues via activity correlation analysis. Secondly, UGT-selective probes can be used to evaluate and predict the role of particular UGTs in drug-drug interactions through enzyme induction or inhibition.26 Thirdly, glucuronidation measured using UGT-selective probe in tissues from different individuals can be used as a phenotype measure to elucidate the functional significance of genetic polymorphisms. 25 Fourthly, UGT probes can be used to screen the potential inhibitors of individual UGT enzymes.28 Finally, they can be used to establish selective functional assays to assess functionality of individual UGT isoforms (can be reflective of metabolic status) in vitro (e.g., hepatocytes), and provide guidance for clinical dosing regimen.26,40

Current available UGT1A1 probes are limited to three compounds: bilirubin, estradiol and etoposide. 28 Bilirubin and estradiol are endogenous compounds, whereas etoposide is cytotoxic, precluding their use in in vivo glucuronidation studies. In this regard, the flavonoid probes here hold greater potential for in vivo prediction of UGT1A1 activity, because they are exogenous and non-toxic.15 As a proof of principle, UGT1A1-selective probes (in vivo) would be of clinical value for predicting SN-38 glucuronidation and determining the proper dose and dosing regimen.11 SN-38 glucuronidation has been shown repeatedly to be an important factor for its gastrointestinal side effects; deficiency in UGT1A1 activity is correlated with more severe side effects in humans.11 It is acknowledged whether these 2 flavonoid probes can be used as a UGT1A1 selective probe in human remains uncertain until appropriate demonstration in vivo.

Interestingly, 3-O-glucuronidation rates of 33′4′THF and 364′THF are also well correlated with hepatic UGT1A9 activities as measured by the glucuronidation rates of propofol at 25 μM using the same set of HLMs (n=12). High significant correlation (R2 ≥ 0.944, p<0.0001) were observed between the glucuronidation of these two flavonoid probes at the 3-OH position and that of propofol (Fig.S5, Supporting Information). Attempt to quantify UGT1A9 using antibody against UGT1A9 obtained from Abnova (Taipei City, Taiwan) was unsuccessful, as the antibody cross-reacted with UGT1A1 (data not shown) and other UGT1A isoforms.7 Therefore, we could not determine the UGT1A9 levels in human liver microsomes. This technical difficulty means that we cannot determine unequivocally if 3-O-glucuronidation rates of 33′4′THF and 364′THF could be used as activity indicators for human UGT1A9, although it could be used as an indicator for glucuronidation rates of propofol, a clinically useful drug.

In addition to correlation analysis, we also used the Km values to determine if regiospecific glucuronidation was similar in expressed UGTs and HLMs. We found that Km values for recombinant UGT1A1 (4′-O-glucuronidation of 33′4′THF and 364′THF) were essentially identical to those for pooled HLM (Figs. 2 & 3), which indicated UGT1A1 was likely the predominant enzyme that catalyzed the 4′-O-glucuronidation. With this additional criterion, 4′-O-glucuronide of two flavonoids were considered the excellent markers for UGT1A1. By contrast, The Km values for recombinant UGT1A9 (3-O-glucuronidation of 33′4′THF and 364′THF) were, respectively, ∼17 (33′4′THF) and ∼ 2.5 (364′THF) times lower than those for pooled HLM (Figs. 2 & 3). The strikingly higher Km value of HLM than the target recombinant UGT, as also had been found for propofol (Fig.S3B) 41,42 could arise from the “membrane effect” (or “albumin effect”) proposed by Miners et al.28 It might also suggest that other UGT isoforms could contribute to the metabolism. 25 These isoforms most likely are UGT2B7 (for 33′4′THF) and UGT1A1 (for 364′THF), inferred from the reaction-phenotyping data (Fig.1). Hence, it is necessary to reduce the low background glucuronidation activities resulted from the off-target UGTs, and to use these flavonoid probes at lower concentrations (e.g., 0.625 μM for the flavonoid probes, much lower than their reported Km values in HLMs).

It is noteworthy that UGT1A1 expression-activity correlation did not hold between recombinant UGT1A1 and HLMs. Compared to pHLM, recombinant UGT1A1 had notably higher UGT1A1 expression in Western blot, but similar activities towards estradiol (3-glucuronide), 33′4′THF and 364′THF (4′-O-glucuronides) (Figs.2-3 and Fig.S3). The catalytic differences might be contributed by UGT protein-protein interactions (hetero-dimerization or hetero-oligomers) in HLMs.43,44 There are another two possibilities that cannot be ruled out: 1) protein separation and/or binding to the membrane during Western blotting were affected by the differences in the sample matrices; 2) over-expression of UGT1A1 in insect cells may lead to the accumulation of inactive enzyme. Further studies are warranted to address this discrepancy.

In conclusion, this study presented two flavonoids (4′-O-glucuronidation), whose regioselective glucuronidation can be used as in vitro selective probes for hepatic UGT1A1, and hold great promise for use as in vivo probes as well. The selectivity of UGT1A1 towards the proposed probes was systematically evaluated via studies including recombinant UGT phenotyping, individual UGT contribution estimation, and activity correlation analysis. UGT1A1 and 1A9 are the main isoforms responsible for glucuronidating 33′4′THF and 364′THF, but at different positions (1A1, 4′-OH; 1A9, 3-OH). Glucuronidation of these 2 flavonoid probes at 4′-OH position by UGT1A1 were well correlated with estradiol-3-glucuronidation (a well-recognized and widely used UGT1A1 probe) and SN-38 glucuronidation (drug's toxicity is associated with UGT1A1 function). The results indicated that 4′-O-glucuronidation of 33′4′THF and 364′THF is excellent markers for UGT1A1, and for UGT1A1-mediated glucuronidation of SN-38. Future work should assess the selectivity of these probes in in vivo glucuronidation studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM070737) to MH.

Abbreviations used

- UGTs

UDP-glucuronosyltransferases

- UPLC

ultra performance liquid chromatography

- MS

mass spectroscopy

- OG

O-glucuronide or O-glucuronidation

- THF

trihydroxyflavone

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- HLM

human liver microsomes

- pHLM

pooled human liver microsomes

- RAF

relative activity factor

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Tables S1 and S2; Figures S1, S2, S3, S4, S5 and S6. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Tukey RH, Strassburg CP. Human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases: metabolism, expression, and disease. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:581–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiang TK, Ensom MH, Chang TK. UDP-glucuronosyltransferases and clinical drug-drug interactions. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;106:97–132. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu B, Kulkarni K, Basu S, Zhang S, Hu M. First-pass metabolism via UDP-glucuronosyltransferase: a barrier to oral bioavailability of phenolics. J Pharm Sci. 2011 doi: 10.1002/jps.22568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao S, Hu M. Bioavailability challenges associated with development of anti-cancer phenolics. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2010;10:550–67. doi: 10.2174/138955710791384081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackenzie PI, Bock KW, Burchell B, Guillemette C, Ikushiro S, Iyanagi T, Miners JO, Owens IS, Nebert DW. Nomenclature update for the mammalian UDP glycosyltransferase (UGT) gene superfamily. Pharmacogenetics Genomics. 2005;15:677–685. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000173483.13689.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohno S, Nakajin S. Determination of mRNA expression of human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases and application for localization in various human tissues by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:32–40. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.023598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Izukawa T, Nakajima M, Fujiwara R, Yamanaka H, Fukami T, Takamiya M, Aoki Y, Ikushiro S, Sakaki T, Yokoi T. Quantitative analysis of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A and UGT2B expression levels in human livers. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:1759–68. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.027227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radominska-Pandya A, Czernik PJ, Little JM, Battaglia E, Mackenzie PI. Structural and functional studies of UDP-glucuronosyltransferases. Drug Metab Rev. 1999;31:817–899. doi: 10.1081/dmr-100101944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emoto C, Murayama N, Rostami-Hodjegan A, Yamazaki H. Methodologies for Investigating Drug Metabolism at the Early Drug Discovery Stage: Prediction of Hepatic Drug Clearance and P450 Contribution. Curr Drug Metab. 2010;11:678–85. doi: 10.2174/138920010794233503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujita K, Sparreboom A. Pharmacogenetics of irinotecan disposition and toxicity: a review. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2010;5:209–17. doi: 10.2174/157488410791498806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Dwyer PJ, Catalano RB. Uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A1 and irinotecan: practical pharmacogenomics arrives in cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4534–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beutler E, Gelbart T, Demina A. Racial variability in the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1 (UGT1A1) promoter: a balanced polymorphism for regulation of bilirubin metabolism? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8170–8174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crozier A, Jaganath IB, Clifford MN. Dietary phenolics: chemistry, bioavailability and effects on health. Nat Prod Rep. 2009;26:1001–43. doi: 10.1039/b802662a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeong EJ, Liu X, Jia X, Chen J, Hu M. Coupling of conjugating enzymes and efflux transporters: impact on bioavailability and drug interactions. Curr Drug Metab. 2005;6:455–68. doi: 10.2174/138920005774330657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu M. Commentary: bioavailability of flavonoids and polyphenols: call to arms. Mol Pharm. 2007;4:803–6. doi: 10.1021/mp7001363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joseph TB, Wang SW, Liu X, Kulkarni KH, Wang J, Xu H, Hu M. Disposition of flavonoids via enteric recycling: enzyme stability affects characterization of prunetin glucuronidation across species, organs, and UGT isoforms. Mol Pharm. 2007;4:883–894. doi: 10.1021/mp700135a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang L, Singh R, Liu Z, Hu M. Structure and Concentration Changes Affect Characterization of UGT Isoform-Specific Metabolism of Isoflavones. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:1466–1482. doi: 10.1021/mp8002557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang L, Ye L, Singh R, Wu B, Lv C, Zhao J, Liu Z, Hu M. Use of Glucuronidation Fingerprinting to Describe and Predict mono- and di- Hydroxyflavone Metabolism by Recombinant UGT Isoforms and Human Intestinal and Liver Microsomes. Mol Pharm. 2010;7:664–79. doi: 10.1021/mp900223c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou Q, Zheng Z, Xia B, Tang L, Lv C, Liu W, Liu Z, Hu M. Use of isoform-specific UGT metabolism to determine and describe rates and profiles of glucuronidation of wogonin and oroxylin A by human liver and intestinal microsomes. Pharm Res. 2010;27:1568–83. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0148-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen YK, Chen SQ, Li X, Zeng S. Quantitative regioselectivity of glucuronidation of quercetin by recombinant UDP-glucuronosyltransferases 1A9 and 1A3 using enzymatic kinetic parameters. Xenobiotica. 2005;35:943–954. doi: 10.1080/00498250500372172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lépine J, Bernard O, Plante M, Têtu B, Pelletier G, Labrie F, Bélanger A, Guillemette C. Specificity and regioselectivity of the conjugation of estradiol, estrone, and their catecholestrogen and methoxyestrogen metabolites by human uridine diphospho-glucuronosyltransferases expressed in endometrium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5222–32. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brill SS, Furimsky AM, Ho MN, Furniss MJ, Li Y, Green AG, Bradford WW, Green CE, Kapetanovic IM, Iyer LV. Glucuronidation of trans-resveratrol by human liver and intestinal microsomes and UGT isoforms. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2006;58:469–79. doi: 10.1211/jpp.58.4.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohno S, Kawana K, Nakajin S. Contribution of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 and 1A8 to morphine-6-glucuronidation and its kinetic properties. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:688–94. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.019281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu B, Morrow JK, Singh R, Zhang S, Hu M. 3D-QSAR Studies on UGT1A9-mediated 3-O-Glucuronidation of Natural Flavonols Using a Pharmacophore-based CoMFA Model. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;336:403–13. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.175356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Court MH. Isoform-selective probe substrates for in vitro studies of human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases. Methods Enzymol. 2005;400:104–16. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)00007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donato MT, Montero S, Castell JV, Gómez-Lechón MJ, Laboz A. Validated assay for studying activity profiles of human liver UGTs after drug exposure: inhibition and induction studies. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;396:2251–63. doi: 10.1007/s00216-009-3441-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stone AN, Mackenzie PI, Galetin A, Houston JB, Miners JO. Isoform selectivity and kinetics of morphine 3- and 6-glucuronidation by human udp-glucuronosyltransferases: evidence for atypical glucuronidation kinetics by UGT2B7. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31:1086–9. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.9.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miners JO, Mackenzie PI, Knights KM. The prediction of drug-glucuronidation parameters in humans: UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzyme-selective substrate and inhibitor probes for reaction phenotyping and in vitro-in vivo extrapolation of drug clearance and drug-drug interaction potential. Drug Metab Rev. 2010;42:189–201. doi: 10.3109/03602530903210716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu B, Xu B, Hu M. Regioselective Glucuronidation of Flavonols by Six Human UGT1A Isoforms. Pharm Res. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0418-5. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh R, Wu B, Tang L, Hu M. Uridine Diposphate Glucuronosyltransferases Isoform-Dependent Regiospecificity Of Glucuronidation Of Flavonoids. J Agric Food Chem. 2011 doi: 10.1021/jf1041454. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh R, Wu B, Tang L, Liu Z, Hu M. Identification of the Position of Mono-O-Glucuronide of Flavones and Flavonols by Analyzing Shift in Online UV Spectrum (λmax) Generated from an Online Diode-arrayed Detector. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:9384–95. doi: 10.1021/jf904561e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Houston JB, Kenworthy KE. In vitro-in vivo scaling of CYP kinetic data not consistent with the classical Michaelis-Menten model. Drug Metab Dispo s. 2000;28:246–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uchaipichat V, Mackenzie PI, Guo XH, Gardner-Stephen D, Galetin A, Houston JB, Miners JO. Human udp-glucuronosyltransferases: isoform selectivity and kinetics of 4-methylumbelliferone and 1-naphthol glucuronidation, effects of organic solvents, and inhibition by diclofenac and probenecid. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32:413–23. doi: 10.1124/dmd.32.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rouguieg K, Picard N, Sauvage FL, Gaulier JM, Marquet P. Contribution of the different UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) isoforms to buprenorphine and norbuprenorphine metabolism and relationship with the main UGT polymorphisms in a bank of human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38:40–5. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.029546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou J, Tracy TS, Remmel RP. Correlation between Bilirubin Glucuronidation and Estradiol-3-Gluronidation in the Presence of Model UGT1A1 Substrates/Inhibitors. Drug Metab Dispos. 2011;39:322–9. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.035030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang D, Zhang D, Cui D, Gambardella J, Ma L, Barros A, Wang L, Fu Y, Rahematpura S, Nielsen J, Donegan M, Zhang H, Humphreys WG. Characterization of the UDP glucuronosyltransferase activity of human liver microsomes genotyped for the UGT1A1*28 polymorphism. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35:2270–80. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.017806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sten T, Bichlmaier I, Kuuranne T, Leinonen A, Yli-Kauhaluoma J, Finel M. UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) 2B7 and UGT2B17 display converse specificity in testosterone and epitestosterone glucuronidation, whereas UGT2A1 conjugates both androgens similarly. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:417–23. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.024844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanioka N, Ozawa S, Jinno H, Ando M, Saito Y, Sawada J. Human liver UDP-glucuronosyltransferase isoforms involved in the glucuronidation of 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin. Xenobiotica. 2001;31:687–99. doi: 10.1080/00498250110057341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathijssen RH, van Alphen RJ, Verweij J, Loos WJ, Nooter K, Stoter G, Sparreboom A. Clinical pharmacokinetics and metabolism of irinotecan (CPT-11) Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2182–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonora-Centelles A, Donato MT, Lahoz A, Pareja E, Mir J, Castell JV, Gómez-Lechón MJ. Functional characterization of hepatocytes for cell transplantation: customized cell preparation for each receptor. Cell Transplant. 2010;19:21–8. doi: 10.3727/096368909X474267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soars MG, Ring BJ, Wrighton SA. The effect of incubation conditions on the enzyme kinetics of udp-glucuronosyltransferases. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31:762–7. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.6.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shimizu M, Matsumoto Y, Yamazaki H. Effects of propofol analogs on glucuronidation of propofol, an anesthetic drug, by human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Lett. 2007;1:77–9. doi: 10.2174/187231207779814355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fujiwara R, Nakajima M, Oda S, Yamanaka H, Ikushiro S, Sakaki T, Yokoi T. Interactions between human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 2B7 and UGT1A enzymes. J Pharm Sci. 2010;99:442–54. doi: 10.1002/jps.21830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fujiwara R, Nakajima M, Yamanaka H, Katoh M, Yokoi T. Interactions between human UGT1A1, UGT1A4, and UGT1A6 affect their enzymatic activities. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35:1781–7. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.016402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.