Abstract

Objective

Since clinical and biological research and optimal clinical practice require stability of diagnoses over time, we determined stability of ICD-10 psychotic-disorder diagnoses, and sought predictors of diagnostic instability.

Methods

Patients (N=500) hospitalized for first-psychotic illnesses were diagnosed by ICD-10 criteria at baseline and 24 months, based on extensive prospective assessments, to evaluate the longitudinal stability of specific categorical diagnoses, and predictors of diagnostic change.

Results

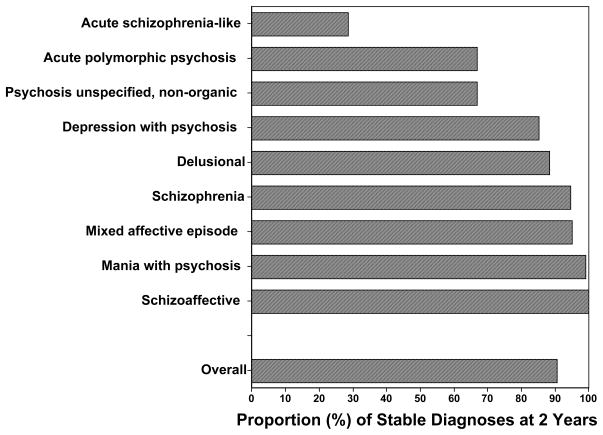

Diagnostic-stability averaged 90.4%, ranking: schizoaffective disorder (100%) > mania with psychosis (99.0%) > mixed-affective episode (94.9%) > schizophrenia (94.6%) > delusional disorder (88.2%) > severe, psychotic, depressive episode (85.2%) > acute psychosis with/without schizophrenia symptoms = unspecified psychosis (all 66.7%) ≫ acute schizophrenia-like psychosis (28.6%). Diagnoses changed by 24 months of follow-up, to: schizoaffective disorders (37.5%), bipolar disorder (25.0%), schizophrenia (16.7%) or unspecified non-organic psychosis (8.3%), mainly through emerging affective features. By logistic-regression, diagnostic-change was associated with Schneiderian first-rank psychosis symptoms at intake > lack of premorbid substance use.

Conclusions

We found some psychotic-disorder diagnoses to be more stable by ICD-10 than DSM-IV criteria in the same patients, with implications for revisions of both diagnostic systems.

Keywords: diagnosis, stability, first-episode, follow-up, ICD-10, prediction, psychosis

“The truth of aesthetically satisfying and didactically convenient classifications can be tested only in the actual application of them.”

Karl Jaspers 1

Introduction

The importance of establishing sound, categorical or syndromal, clinical diagnoses of major psychiatric disorders with both cross-sectional validity and stability over time has long been recognized as clinically crucial and essential for progress in neurobiological as well as clinical research.1–3 International taxonomies represented by the World Health Organization’s (International Classification of Diseases [ICD of WHO]) and American Psychiatric Association’s (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM of APA]) systems involve standardized and operationalized descriptive criteria, and a longitudinal perspective.4,5 More objective, biologically-based methods to support psychiatric diagnoses continue to be sought, but are unlikely soon to displace clinical, descriptive, phenomenological diagnosis, or limit the need for biologists and nosologists to collaborate.6

Diagnosis of psychotic disorders may be especially unstable, owing to: [a] insufficient and potentially unreliable information, especially if elicited only from patients; [b] fluctuating manifestations or detection of psychopathology over time, and later emergence or change of initially unclear symptoms;7,8 [c] symptom-modifying effects of treatment, substance-abuse, co-morbid psychiatric or medical disorders, and prolonged disability or institutional care;8 premorbid temperamental characteristics or personality disorders,9 and developmental factors related to age;10,11 as well as [d] standardized diagnostic schemes of potentially limited validity,4,5 with simplified or arbitrary criteria for particular features, symptom-duration, and functional impairment that belie the richness, complexity, fluidity, and nuances of illness phenomena arising early in most disorders.11–19 In addition, some diagnostic concepts remain inadequately validated and may simply be unreliable, notably including transient acute-psychotic disorders and schizoaffective syndromes, or may be applied differently to particular clinical, ethnic, sex or age-groups, highlighting the need to consider cultural variations in psychopathological presentations and illness-stability over time.20–23

Given clinical and research requirements for more reliable diagnoses despite limited information and typically brief observation times, it is highly desirable that initial standardized, syndromal diagnoses remain longitudinally stable or follow predictable courses. It is therefore important to test diagnostic stability by systematic and prospective, long-term assessments, if only to document levels of longitudinal congruence of specific diagnoses and to identify early predictors of later diagnostic change. Several modern studies have considered the stability of some psychotic disorders followed from onset,11,14,18,24–38 but few have considered predictors of particular diagnostic changes over a wide spectrum of disorders.26,31,32,35–38 Specifically, studies of longitudinal stability of specific ICD-10 psychotic-disorder diagnoses include acute and transient psychotic disorder [ATPD] subtypes among acute polymorphic psychotic disorders [APPD],39–44 schizophrenia,45,46 or mood disorders.47–49 However, we found only two studies that investigated diagnostic stability over time in the broad range of ICD-10 functional psychoses, and neither explored factors predicting diagnostic change or stability over time.25,28

Based on these considerations and our previous findings on diagnostic stability and its predictors among DSM-IV psychotic disorders,38 we again evaluated diagnostic stability over two years, of a broad range of initially considered psychotic disorders based on ICD-10 criteria, among 517 patients enrolled in the McLean-Harvard International First-Episode Project. We hypothesized that stability of some initial ICD-10 diagnoses would vary over time, and that early clinical factors might predict later diagnostic instability. As secondary aims, we considered how initial affective and psychotic components of illnesses changed over time, and whether new diagnoses were more likely to emerge through newly-prominent affective versus non-affective features.

Methods

Subjects and diagnostic assessments

Subjects were among the first 517 patients entering the McLean-Harvard International First-Episode Project based at McLean Hospital and the University of Parma in 1989–2003. Project protocols were reviewed annually and approved by the McLean Hospital IRB and Ethical Committee of the University of Parma Medical Center, through 2008. For inclusion, all subjects presented in a first-lifetime episode of affective (manic, mixed, or depressive) or non-affective psychotic illness, and gave written informed consent for participation and anonymous, aggregate reporting of findings. Intake exclusion criteria were: [a] acute intoxication or withdrawal associated with drug or alcohol abuse, or any delirium; [b] previous psychiatric hospitalization, unless for detoxification; [c] documented mental retardation (WAIS-tested IQ <70) or other organic mental disorder; [d] index syndromal illness present >6 months, or any previous syndromal episode; or [e] prior total treatment with an antipsychotic agent for ≥4 weeks, or an antidepressant or mood-stabilizer for ≥3 months.

Diagnoses for analyses based on ICD-10 criteria, were made by a highly trained diagnostician with years of clinical-research experience (PS), employing historical prospective methods 50 and kept blinded to initial (baseline) and follow-up consensus and SCID-based diagnoses. All information on illness antecedents, prodromes, onset, presentation, and course was derived from medical records (including clinical narratives of hospital-course, and notes from initial and follow-up assessments, semi-structured interviews with patients, families and treating or primary-care clinicians) as well as research records (including psychopathological rating scales, and data derived from standardized clinical interviews including the SCID 51)—all with diagnostic formulations excluded for this study. This information was reviewed to define the most appropriate ICD-10 diagnosis in each case at baseline and again at two years. These 1000 assessments were made in random-order by the same expert-investigator (PS) over several months, with 3–6 weeks between individual assessments, making recollection bias unlikely. In addition, as a test of reliability of the assessments, we drew a random sample of 50 patients with two, categorical, ICD-10 diagnoses, and found agreement in 46 (92.0%), even without correcting for effects of natural diagnostic change over time. Diagnostic procedures of the First-Episode project for other studies applied DSM-IV criteria or updated diagnoses according to current DSM classifications based on SCID-P evaluations at baseline and at 24-months.37,38 We also estimated age-at-onset of primary illnesses, timing of premorbid features, and the presence and timing of lifetime co-morbid psychiatric or substance-use disorders (SCID-based), as well as general medical, neurological, and personality disorders determined clinically and recorded systematically according to DSM-IV requirements. Primary diagnoses met current ICD-10 criteria in 2008, based on the 1992 Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines,4 which were compared to DSM-IV-TR diagnoses.38 Clinical assessment methods have been detailed previously.37,38

Data analyses

We compared subjects with ICD-10-based, categorical diagnoses considered stable versus changed by 24 months to assess associated patient-characteristics, using one-way ANOVA (F) for continuous variables, and contingency tables (χ2 or Fisher exact-p) for categorical factors, with defined degrees-of-freedom (df). We entered measures with at least suggestive differences (p<0.10) in initial bivariate comparisons, stepwise, into a logistic regression model to identify factors independently associated with diagnostic change, reported as Odds Ratios (OR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI). Averages are means with standard deviations (±SD). Analyses were based on commercial statistical programs (Stata-9®, Stata Corp., College Station, TX; Statview-5®, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Subject characteristics and initial diagnoses

Of 517 first-episode psychotic subjects assessed, 17 (3.3%) were lost to follow-up, leaving 500 (96.7%) for two (baseline and 2-year) diagnostic assessments (100%). Most subjects were men (55.0%) and estimated age-at-onset over the range of first-psychotic syndromes averaged (± SD) 31.7±13.7 years. Patients enrolled at McLean Hospital (n=406, 81.2%) and the University of Parma Medical Center (n=94, 18.8%), followed identical protocols. Initial diagnoses included affective-psychotic syndromes (mixed-affective episode, mania with psychotic symptoms, severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms; n=309, 61.8%), and non-affective disorders (schizophrenia, APPD, delusional disorder, unspecified non-organic psychosis, and acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder; n=143, 28.6%), as well as schizoaffective disorders (n=48, 9.6%; Table 1). Among schizophrenia diagnoses at baseline (n= 56/500; 11.2%), the undifferentiated type was most prevalent (n= 22, 39.3%), hebephrenic (n=15, 26.8%) and paranoid types (n=11, 19.6%) intermediate, and catatonic (n= 4, 7.1%) and simple (n=1, 1.8%) types, uncommon.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 500 first-episode ICD-10 psychotic disorder patients

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Subjects {N [%]) | |

| All cases | 500 (100%) |

| Men | 275 (55.0%) |

| Women | 225 (45.0%) |

| Age at onset (years) by initial ICD-10 diagnosis | |

| Overall | 31.7 ± 13.7 |

| Delusional | 41.4 ± 15.9 |

| Psychotic depression | 37.8 ± 18.2 |

| Unspecified non-organic psychosis | 35.4 ± 13.0 |

| Acute polymorphic without schizophrenic symptoms | 33.3 ± 16.4 |

| Manic or mixed-affective episodes | 31.5 ± 13.2 |

| Acute polymorphic with schizophrenic symptoms | 28.8 ± 10.8 |

| Acute schizophrenia-like psychosis | 28.0 ± 7.1 |

| Schizophrenia | 27.9 ± 8.9 |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 27.5 ± 10.3 |

| DSM-IV co-morbidities | |

| Substance use disorders | |

| All types | 256 (51.2%) |

| Alcohol | 228 (89.1%) |

| Drugs | 155 (60.5%) |

| Both | 126 (49.2%) |

| Axis II personality disorders | 115 (23.0%) |

| Cluster A | 39 (33.9%) |

| Cluster B | 55 (47.8%) |

| Cluster C | 21 (18.3%) |

| Anxiety disorders | 86 (17.2%) |

| Phobias | 35 (41.9%) |

| PTSD | 29 (33.7%) |

| Panic disorder | 26 (30.2%) |

| OCD | 25 (29.1%) |

| GAD | 9 (10.5%) |

| Prevalence of initial ICD-10 diagnoses (%, by rank) | |

| Mixed-affective episode | 156 (31.2%) |

| Mania with psychosis | 99 (19.8%) |

| Schizophrenia | 56 (11.2%) |

| Depression with psychosis | 54 (10.8%) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 48 (9.6%) |

| Acute polymorphic psychosis with schizophrenic symptoms | 27 (5.4%) |

| Acute polymorphic psychosis without schizophrenic symptoms | 21 (4.2%) |

| Delusional disorder | 17 (3.4%) |

| Unspecified non-organic psychosis | 15 (3.0%) |

| Acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder | 7 (1.4%) |

| Changed initial diagnoses (%, by rank) | |

| Acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder | 5/7 (71.4%) |

| Acute polymorphic psychosis with schizophrenic symptoms | 9/27 (33.3%) |

| Acute polymorphic psychosis without schizophrenic symptoms | 7/21 (33.3%) |

| Unspecified non-organic psychosis | 5/15 (33.3%) |

| Depression with psychosis | 8/54 (14.8%) |

| Delusional disorder | 2/17 (11.8%) |

| Schizophrenia | 3/56 (5.4%) |

| Mixed-affective episode | 8/156 (5.1%) |

| Mania with psychosis | 1/99 (1.0%) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 0/48 (0.0%) |

Overall diagnostic stability averaged 90.4% (452/500). Drugs abused by 155/500 patients included: cocaine (30.9%), hallucinogens (28.5%), heroin (18.4%), methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“ecstasy,” 14.5%), sedatives or hypnotics (14.0%), and stimulants (14.0%).

At baseline, SCID-P based lifetime co-morbid diagnoses included: substance-use disorders (51.2%) and anxiety disorders (17.2%), and clinically determined Axis II lifetime co-morbidity with personality disorders recorded according to DSM-IV requirements reached 23.0% (Table 1). Substance-use disorders were associated (in descending incidence) with the following initial ICD-10 diagnoses: mixed affective episode (69.2%), mania with psychosis (57.6%), schizoaffective disorder (56.3%), severe depression with psychosis (51.8%), acute schizophrenia-like disorder (42.9%), schizophrenia (33.9%), unspecified non-organic psychosis (33.3%), APPD without symptoms of schizophrenia (23.8%), delusional disorder (11.8%), or APPD with symptoms of schizophrenia (11.1% of cases; χ2 [df=9] = 73.9 p<0.0001).

Based on initial diagnoses, mean onset-age was 31.7 years, and onset-age ranked by diagnosis as: delusional disorder (41.4) > severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms (37.8) > unspecified non-organic psychosis (35.4) > APPD without symptoms of schizophrenia (33.3) > mania with psychotic symptoms (31.5) = mixed-affective episode (31.5) > APPD with symptoms of schizophrenia (28.8) ≥ acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder (28.0) ≥ schizophrenia (27.9) ≥ schizoaffective disorder (27.5 years; Table 1).

Changes in diagnosis at two-year follow-up

Initial ICD-10 diagnoses changed in 48/500 cases (9.6%), with a positive predictive value of initial diagnoses of 90.4%.52 This overall stability contrasts with 75.3% found with DSM-IV consensus diagnoses of the same cases.38 Positive predictive value was 1.2-times greater among subjects with ICD-10 schizoaffective (48/48, 100.0%) or major affective episodes with psychotic features (292/309, 94.5%) than those diagnosed with ICD-10 non-affective psychoses (112/143, 78.3%; χ2 [df=2] = 35.1, p<0.0001; Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Changes in ICD-10 diagnosis: First-episode psychotic disorders

| Initial diagnosis (n [%]) | Follow-Up Diagnoses (n [%]) |

|---|---|

| Acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder (7 [1.4%]) | Acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder (2 [28.6%]) Schizophrenia (4 [57.1%]) Recurrent depressive disorder (1 [14.3%])a |

| Unspecified non-organic psychosis (15 [3.0%]) | Unspecified non-organic psychosis (10 [66.7%]) Schizoaffective disorder (3 [20.0%]) Bipolar affective disorder (1 [6.7%])a Delusional disorder (1 [6.7%]) |

| Acute polymorphic psychosis with schizophrenic symptoms (27 [5.4%]) | Acute polymorphic psychosis with schizophrenic symptoms (18 [66.7%]) Bipolar affective disorder (3 [11.1%]) a Schizophrenia (3 [11.1%]) Recurrent depressive disorder (1 [3.7%])a Mania with psychosis (1 [3.7%])b Depression with psychosis (1 [3.7%])b |

| Acute polymorphic psychosis without schizophrenic symptoms (21 [4.2%]) | Acute polymorphic psychosis without schizophrenic symptoms (14 [66.7%]) Unspecified non-organic psychosis (4 [19.0%]) Bipolar affective disorder (2 [9.5%])a Delusional disorder (1 [4.8%]) |

| Depression with psychosis (54 [10.8%]) | Any depressive disorder (46 [85.2%])c

Recurrent depressive disorder (31 [57.4%])a Depression with psychosis (15 [27.8%])b Bipolar affective disorder (6 [11.1%])a Schizoaffective disorder (1 [1.9%]) Schizophrenia (1 [1.9%]) |

| Delusional disorder (17 [3.4%]) | Delusional disorder (15 [88.2%]) Schizoaffective disorder (2 [11.8%]) |

| Schizophrenia (56 [11.2%]) | Schizophrenia (53 [94.6%]) Schizoaffective disorder (3 [5.4%]) |

| Mixed-affective episode (156 [31.2%]) |

Any mixed or bipolar (148 [94.9%])c Bipolar affective disorder (126 [80.8%])a Mixed-affective episode (22 [14.1%])b Schizoaffective disorder (8 [5.1%]) |

| Mania with psychosis (99 [19.8%]) | Any manic or bipolar (98 [99.0%])c

Bipolar affective disorder (84 [84.8%])a Mania with psychosis (14 [14.1%])b Schizoaffective (1 [1.0%]) |

| Schizoaffective disorder (48 [9.6%]) | Schizoaffective disorder (48 [100%]) |

Listed in rank-order of worst-to-best diagnostic stability among N=500 patients with initial and 2-year ICD-10 diagnoses. Boldface indicates proportion of initial diagnoses remaining unchanged (positive predictive power).

Recurrent illnesses;

single-episode in two years of follow-up;

total of single plus recurrent episodes.

Table 3.

Categorical outcomes of ICD-10 diagnoses during follow-up

| New Categories | From Non-Affective | From Affective | From Schizoaffective | From All Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| To affective | 10/16 (62.5%) | 6/16 (37.5%) | 0 (0.00%) | 16/48 (33.3%) |

| To non-affective | 13/14 (92.9%) | 1/14 (7.1%) | 0 (0.00%) | 14/48 (29.2%) |

| To schizoaffective | 8/18 (44.4%) | 10/18 (55.6%) | 0 (0.00%) | 18/48 (37.5%) |

| All changes | 31/143 (21.7%) | 17/309 (5.5%) | 0/48 (0.00%) | 48/500 (9.6%) |

| Stable diagnoses | 112/143 (78.3%) | 292/309 (94.5%) | 48/48 (100%) | 452/500 (90.4%) |

| Baseline Totals | 143/143 (100%) | 309/309 (100%) | 48/48 (100%)) | 500/500 (100%) |

Diagnostic changes (9.6% of all cases) are specified in Table 2. Initially, there were 309 diagnoses of affective psychoses (61.8%), 143 of non-affective disorders (28.6%), and 48 of schizoaffective disorder (9.6%). At follow-up, the distribution was: affective (308; 61.6%), non-affective (126; 25.2%), and schizoaffective (66; 13.2%), indicating a 1.4-fold increase of schizoaffective diagnoses, a 0.2% decrease of affective disorder diagnoses, and 3.4% loss among non-affective diagnoses (χ2 [df=4] = 771, p<0.0001).

Most changes involved later-diagnosed schizoaffective disorders (18 cases, 37.5% of the 48 revised diagnoses: 8 from initial non-affective categories, and 10 initially affective cases including 8 initial mixed-episode diagnoses, one initially considered mania and another initially diagnosed as severe depression). New schizoaffective diagnoses involved emerging affective features in previously non-affective conditions, 1.8-times more often than the opposite (8/143 [5.6%] versus 10/309 [3.2%]; χ2 [df=2] = 771, p<0.0001).

The second-most prevalent changed diagnosis was bipolar affective disorder (12/48 [25.0%]: 6 initially diagnosed severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms, 3 APPD with symptoms of schizophrenia, 2 APPD without symptoms of schizophrenia, and 1 initial unspecified non-organic psychosis). Third were new diagnoses of schizophrenia (8/48 changes, or 16.7%: 4 initially considered acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder, 3 initial APPD with symptoms of schizophrenia, and 1 with apparent severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms). Fourth were shifts to unspecified non-organic psychosis (4/48 = 8.3%, all from APPD without symptoms of schizophrenia). These four final categories accounted for 42/48, or 87.5% of new ICD-10 psychotic-disorder diagnoses.

The remaining 6 new diagnoses (12.5%) included 2 cases of recurrent depressive disorder (one each from acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder and APPD with symptoms of schizophrenia), 2 delusional disorder (one each from unspecified non-organic psychosis, and APPD without schizophrenia symptoms), as well as one case each of mania with psychotic symptoms and severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms, both being initially diagnosed as APPD with symptoms of schizophrenia.

Initial ICD-10 diagnoses of both mania with psychotic symptoms and mixed-affective episode held up best (99.0% [98/99] and 94.9% [148/156]), as only 1.0% (1/99) and 5.1% (8/156), respectively, changed to schizoaffective disorder at 2-year follow-up. These results were similar to our previous analyses of DSM-IV diagnoses.38 Also among affective-disorder diagnoses, 85.2% (46/54) of cases initially considered to have a severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms remained stable, and 8 changed (6 to bipolar affective disorder, 1 each to schizoaffective disorder or schizophrenia). Among non-affective diagnoses, schizophrenia persisted in 94.6% of patients (with only 3 changes to schizoaffective disorder, including 2 from paranoid and 1 from undifferentiated subtypes), and delusional disorder remained stable in 88.2% of cases. Most short-duration or initially nonspecific syndromes, not surprisingly, changed to various alternatives, with moderate retention rates for APPD with and without symptoms of schizophrenia (66.7%) as well as unspecified non-organic psychosis (66.7%), and low persistence of initial acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder diagnoses (28.6%; Figure).

Figure.

Diagnostic stability of initial ICD-10 diagnoses (with prevalence [%] from Table 1) in 500 first-episode psychotic disorder patients at first-lifetime hospitalization, ranked by diagnostic stability (% remaining unchanged) for the same subjects at 24 months follow-up. Note that diagnostic stability ranged from 100% for schizoaffective disorders (48 cases) to 28.6% for acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder (7 cases initially).

Of 48 total diagnostic changes, 31 (64.6%) involved diagnoses initially considered non-affective (31/143 = 21.7%; Tables 2 and 3), of whom, 8/31 (25.8%) shifted to schizoaffective disorders (from initial unspecified non-organic psychosis [n=3], schizophrenia [n=3], or delusional disorder [n=2]). Changes to alternative non-affective categories occurred in 13/31 (41.9%) of initially non-affective cases (4 from acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder to schizophrenia, 3 from APPD with symptoms of schizophrenia to schizophrenia, 5 from APPD without symptoms of schizophrenia to unspecified non-organic psychosis [n=4] or delusional disorder [n=1], and 1 from unspecified non-organic psychosis to delusional disorder). There were 10/31 shifts (32.3%) to new affective diagnoses (from APPD with symptoms of schizophrenia to bipolar affective disorder [n=3], mania with psychotic symptoms [n=1], recurrent depressive disorder [n=1], or severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms [n=1], from APPD without symptoms of schizophrenia to bipolar affective disorder [n=2], from acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder to recurrent depressive disorder [n=1], and from unspecified non-organic psychosis to bipolar affective disorder [n=1]).

There were only 17/48 (35.4%) changes of initial affective-disorder diagnoses (of 309 initial affective cases, or 5.5%), including 10/17 (58.8%) new schizoaffective diagnoses arising from: initial diagnoses of mixed-affective episode (n=8), mania or severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms (n=1 each). Shifts within affective categories (n=6) all involved new diagnoses of bipolar affective disorder from initial severe depression, owing to later manic (n=4) or mixed (n=2) episodes. The one new non-affective diagnosis was of schizophrenia, following an initial ICD-10 diagnosis of severe depressive episode.

Initial diagnosis as predictor of final diagnoses

Bayesian analyses 52 of final versus initial diagnoses (not shown) indicate that schizoaffective disorder (100%), mania with psychotic symptoms (99.0%), mixed-affective episode (94.9%), and schizophrenia (94.6%), delusional disorder (88.2%), and severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms (85.2%), had relatively high levels of diagnostic stability or positive predictive value (>85%). In contrast, initial ICD-10-based acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder (28.6%), and diagnoses of unspecified non-organic psychosis and APPD with and without symptoms of schizophrenia (three categories, 66.7%) had lower predictive value (Table 2). Specificity (1.0 minus the false-positive rate) in all categories was ≥83% except for the acute and transient (50%) or unspecified psychotic disorders (64.3%). Sensitivity (1.0 minus the false-negative rate) exceeded 86% in all but 2 categories: acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder, and APPD with and without symptoms of schizophrenia (100%); bipolar affective disorder (95%); severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms (94.1%); schizophrenia (86.9%); and delusional disorder (86.7%), but not unspecified non-organic psychosis (71.4%) and schizoaffective disorder (72.7%).

Predictors of diagnostic instability

Initial bivariate regression modeling indicated that subjects with changed (n=48) versus stable (n=452) ICD-10 diagnoses ranked by statistical significance, as: [a] 4.7 years younger at onset, [b] more likely to present initial Schneiderian first-rank symptoms (FRS 53) of any type (audible thoughts, arguing, commenting, or imperative hallucinated voices; thought-withdrawal, broadcasting or insertion; external influences on bodily functions, arousal, sensations or volition; and delusional perception or attribution of abnormal meanings to real perceptions), [c] experiencing more initial auditory hallucinations, [d] less likely to have a previous substance-use disorder diagnosis, and [e] more likely to present with initial Schneiderian FRS of influence or hallucinations (Table 4A).

Table 4.

Factors associated with ICD-10 diagnostic stability

| A. Bivariate analyses: Factors favoring diagnostic change | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Stable Diagnoses | Changed Diagnoses | F or χ2 | p-value |

| Onset age | 32.8±14.5 | 28.1±9.6 | 10.2 | 0.0015 |

| Any first-rank symptoms | 77.1% | 95.8% | 9.1 | 0.0025 |

| Auditory hallucinations | 44.1% | 64.6% | 7.2 | 0.0072 |

| Any substance-use disorder | 52.8% | 35.4% | 5.2 | 0.021 |

| First-rank influence feelings | 17.7% | 31.3% | 5.2 | 0.023 |

| First-rank hallucinations | 43.8% | 58.3% | 3.7 | 0.05 |

|

B. Multivariate analysis: Factors favoring diagnostic change

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Odds Ratio [95% CI] | χ2 | p-value |

| Any First-Rank symptoms | 6.55 [1.56–27.5] | 6.60 | 0.010 |

| Lack of any substance-use disorder | 1.94 [1.04–3.62] | 4.30 | 0.038 |

Data are percentages of subjects with stated features, or means ± SD; continuous variables are tested with ANOVA (F [df=1; 499]); categorical variables were tested with contingency tables (χ2 [df=1]), with factors in descending order by p-values. Other factors not associated with diagnostic stability included: [a] sex; [b] onset gradual versus acute or subacute; [c] months from initial symptoms to first syndromal illness; [d] specific types of Schneiderian first-rank symptoms other than hallucinations and feelings of influence; [e] visual, olfactory, gustatory, tactile, or somatosensory hallucinations; [f] Capgras misidentification features; [g] cycloid features; [h] other pre-psychotic anxiety disorders or PTSD; [i] personality disorder or cluster-type; [j] previous eating disorder; [k] significant medical, neurological, or surgical co-morbidity, including head-injury, epilepsy, migraine, or allergy, during outpost or prodromal phases; [l] early learning disorder; or [m] study-site.

Logistic regression model based on factors suggested in preliminary bivariate contrasts shown in A: factors favoring diagnostic change are ranked by descending p-values.

Two of these factors were independently associated with diagnostic change in multivariate logistic regression modeling, with factors ranking (by statistical significance) as: [a] any Schneiderian FRS at presentation > [b] lack of an earlier substance-use disorder diagnosis (Table 4B). Other demographic and clinical factors not associated with diagnostic changes included: sex; onset-type; latency of first-episode symptoms to full syndrome; specific Schneiderian FRS other than auditory hallucinations and experiences of influence; non-FRS visual, olfactory, gustatory, tactile, or somatosensory hallucinations; Capgras misidentification features; cycloid features; various pre-psychotic co-morbid DSM psychiatric disorders (including cyclothymia, dysthymia, post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD], other anxiety disorders, eating disorders, or Axis II personality disorders, including clusters A–C), as well as medical or neurological illnesses or early learning disability, and study-site (see Table 4 footnote).

Correlation of ICD-10 versus DSM-IV diagnoses

Based on categories considered comparable in the two leading, modern diagnostic systems, estimates of diagnostic stability were highly correlated. However, for nearly all categories of psychotic-disorder diagnoses, stability of ICD-10 diagnoses was consistently higher than with DSM-IV criteria (Table 5). A noteworthy exception was bipolar disorder, which yielded the same, highest stability of any diagnosis (96.5%). The greatest difference in diagnostic stability was found at the low end, between ICD-10 schizophrenia-like disorders (28.6%) and DSM-IV schizophreniform disorders (10.5% stability), although these diagnoses may not be directly comparable.

Table 5.

Comparisons of ICD-10 and DSM-IV diagnostic stability (%) of psychotic disorders

| Category | ICD-10 | DSM-IV | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia-like or Schizophreniform | 28.6 | 10.5 | 2.7 |

| Psychosis NOS | 66.7 | 51.5 | 1.3 |

| Acute or Brief | 66.7 | 61.1 | 1.1 |

| Major depression with psychosis | 85.2 | 70.1 | 1.2 |

| Delusional disorder | 88.2 | 72.7 | 1.2 |

| Schizophrenia | 94.6 | 75.0 | 1.3 |

| Bipolar disorder | 96.5 | 96.5 | 1.0 |

| Overall | 90.4 | 75.3 | 1.2 |

The diagnostic systems yield highly correlated stability estimates (r = 0.97 [7 diagnoses], p=0.0004), but consistently higher stability (by 10%–270%) with ICD-10 criteria (slope= 1.16 [95% CI: 0.90–1.67]), including the identical, high, values for bipolar disorder.

Discussion

Study strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include prospective and systematic follow-up of a large cohort of 500 first-episode patients assigned categorical, syndromal diagnoses using standardized and reliable methods with a broad range of both ICD-10 affective and non-affective psychotic disorders, based on initial hospitalization and repeated, prospective, systematic, clinical and rating-scale based assessments over 24 months of follow-up, evaluated with formal SCID-P assessments at baseline and 24 months. During follow-up, there was only 3.3% loss due to consistent and intensive pursuit of all subjects. Study-limitations include assignment of ICD diagnostic categories at baseline and 24 months by one expert diagnostician, using extensive, prospectively acquired data, held blind to consensus DSM-IV diagnoses and interpretations of SCID assessments, and considering cases in random-order over many weeks. In addition, there were relatively small samples (n<30) in several categories at intake (especially acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder, unspecified non-organic psychosis, and APPD with and without schizophrenia-like symptoms), reflecting their limited prevalence. Such power-limitations precluded statistical analysis of predictive factors for specific diagnostic changes, and overall analyses reported may not apply to all disorders. Also, these findings for initially hospitalized patients in first psychotic episodes may not apply to samples obtained in other settings (outpatient clinics, community samples, or others).

Stability of specific initial diagnoses

Overall, diagnostic stability of first-episode ICD-10 psychotic disorders in the first two years of follow-up from initial major episodes (90.4%) was significantly greater than previously reported for DSM-IV categories in the same patient-sample (75.3%).38 This superior stability was sustained for all seven psychotic-disorder diagnoses considered to be similar in both classification systems (Table 5). A second main finding was that all 48 initial ICD-10 schizoaffective diagnoses remained stable for two years. In addition, mania with psychotic symptoms remained stable in 99.0% of 99 cases; only one case of mania later changed to schizoaffective disorder, and 14 (14.1%) initially manic patients did not experience a major recurrence within two years. Of 156 cases diagnosed initially as mixed-affective episode, 94.6% remained stable; all 8 changes (5.1%) involved later-emerging psychotic features, with new schizoaffective diagnoses. Another 14.1% had no further episodes within 24 months (Figure, Table 2). Previous studies have reported prevalence of single-episode manic or mixed-states at 0%–55% of cases (usually ≤8%).54,55 Schizophrenia was the fourth-most stable diagnosis (94.6% of 56 unchanged); all changes (5.4%) involved new schizoaffective diagnoses, mostly from the paranoid subtype. Only 4 ICD-10 psychotic-disorder diagnoses (schizoaffective disorder, mania with psychotic symptoms, mixed affective episode, and schizophrenia) remained stable for two years in ≥95% of cases.

The uncommon ICD-10 diagnosis delusional disorder (3.4%) remained stable in 88.2% of cases (Table 2). Such conditions often evolve into schizophrenia or schizoaffective diagnoses, with emergence of hallucinations or formal thought disorder, or of affective features,29 although their relationship to schizophrenias and paraphrenias has been ambiguous for a century.2 Severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms (54 cases) was similarly stable (85.2%), shifting to bipolar affective disorder as later manic or mixed episodes arose (6/8 changes), or to one each of new schizoaffective or schizophrenia diagnoses. Also, among 46 subjects initially diagnosed with severe depressive episode at both intake and two years later, 15 (32.6%) had only a single episode.

Of initial acute polymorphic psychotic disorder (APPD) diagnoses with and without symptoms of schizophrenia (n=32 initially), 33.3% changed to other categories (Tables 1 and 2, Figure). Diagnostic instability was anticipated among psychotic disorders expected to be acute, time-limited, and prognostically favorable, particularly acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder. Initially, this diagnosis was uncommon (n=7 cases), and 71.4% changed to other diagnoses, particularly schizophrenia (Table 2). Diagnostic-instability rates of ICD-10 acute and transient psychotic disorders (ATPD; n=55 or 11.0%, including APPD [n=48] and acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder [n=7]) averaged 46.0% overall, and 33.3% of APPD underwent diagnostic changes. These disorders, in the same patients, may compare best to DSM-IV categories of schizophreniform (89.5%) and brief psychotic disorders (38.9% involved changed diagnoses; 64.2% overall).38 Accordingly, ICD-10 diagnoses of ATPD, particularly the APPD subtypes, may be somewhat more stable, and potentially more reliable and valid constructs than DSM-IV schizophreniform and brief psychotic disorder. Several studies 21,25,39,41,43,44 investigated the incidence, characteristics, and diagnostic stability of ICD-10 acute, transient psychoses, alone or within the broad range of first-episode functional psychoses, generally finding low to moderate overall stability rates (34.4%–57.9%), though relatively high positive predictive power was found among such diagnoses in developing countries (64.4%–73.3%),28,40,42 particularly for the APPD subtypes.40

The present and previous findings 38 indicate limitations of both ICD-10 and DSM-IV diagnostic categories, particularly in attempting to account for acute, non-affective, remitting psychoses.56 Notably, several criteria, including 1–3 months duration required for acute psychoses in both systems, the schizophrenia Criteria-A required for DSM-IV schizophreniform disorder, and lack of negative symptoms for DSM-IV brief psychotic disorder, all seem limited, arbitrary, and fail to capture the complexity of many psychotic disorders. As acute onset is not a criterion for DSM-IV brief psychotic or schizophreniform disorders, but ICD-10 considers onset-type to be crucial, remitting psychoses with non-acute onset and typical cases of schizophrenia and other persistent psychoses, as well as non-affective acute remitting psychoses, may be misclassified, especially by DSM-IV criteria. As highlighted in ICD-10, initial acute-versus-non-acute onset and a remitting-versus-chronic course, as well as prolonged stability during follow-up may be relatively robust criteria for differentiating psychotic-disorder subtypes.56 Also, the relatively high instability of undifferentiated/unspecified psychoses may reflect their possible status as prodromes of more stable conditions such as schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder.57

The present finding of diagnostic stability of ICD-10 APPD diagnoses with and without symptoms of schizophrenia (both 66.7%) might be related partly to the higher prevalence of cycloid features at presentation (64.3% and 66.7%) among longitudinally stable cases of APPD than for other categories (0%–50% stability; not shown), including schizophrenia (1.6%) and schizoaffective disorders (9.1%). Some recent reports comment on the presence of cycloid phenomena, including rapidly-changing moods and activity levels, delusions, confusion or perplexity, anxiety or ecstasy, not only to distinguish APPD from chronic psychotic illnesses, but also to predict a more favorable course and outcome.41,58–60

Diagnostic stability of schizoaffective disorder

Schizoaffective disorder is of particular interest owing to variance in both concepts and criteria. With ICD-10 criteria, its prevalence increased from 9.6% to 13.2% within two years, and it accounted for 37.5% of new diagnoses; moreover, this diagnosis remained stable in 100% of the 48 patients initially so-diagnosed, to represent the most stable ICD-10 psychotic disorder diagnosis (Table 2). In contrast, based on DSM-IV criteria, schizoaffective disorder was rare initially.38 Such striking differences probably reflect: [a] allowance in ICD-10 of broad temporal relations between schizophrenia-like (psychotic) and affective symptoms;4 [b] narrow definitions of psychotic phenomena in DSM-IV Criterion-B; and [c] the required meeting of criteria for a major mood episode in DSM-IV.5 John Kasanin’s 61 concept of the schizoaffective syndrome as the acute admixture or rapid succession of schizophrenia-like and mood features anticipated the ICD-10 concept,4 whose essential criterion is prominence of both affective and psychotic symptoms in the same episode or within a few days. The more restrictive DSM-IV 5 Criterion-B required for schizoaffective disorder (“during the same period of illness there have been delusions or hallucinations for ≥2 weeks in the absence of prominent mood symptoms”) extends the requirement of “an uninterrupted period of illness of at least 1 month, during which at some time there is a 1–2-week major mood episode as well as symptoms meeting DSM-IV Criterion-A for schizophrenia,” and narrowly limits potential psychotic phenomena to the occurrence of delusions or hallucinations alone.

Later emergence of affective features led 5.6% of initial ICD-10 non-affective cases to be diagnosed later as schizoaffective, whereas 3.2% initially considered affective-disorders later manifested sustained psychotic features, indicating that new affective features were the more likely route to ICD-10 schizoaffective diagnoses (Table 3), similar to DSM-IV criteria.38 In other studies, relative contributions of late affective versus psychotic features were not specified.18,25–27,62 From a clinical and nosologic viewpoint, later emergence of affective components within initially psychotic conditions might reflect the phenomenological nature of acute psychoses in which affective expression is overwhelmed by pervasive positive psychotic symptoms, or affective features are quantitatively or temporally insufficient to meet diagnostic criteria for an affective psychotic disorder.21,25,39–44 In addition, from the perspective of clinical psychopathology, as pointed out by Kurt Schneider,53 subsequent appearance of affective components in initial non-affective psychotic states might be triggered by the profound existential catastrophe of first-rank symptoms (FRS), which undermine the unity of the self as the center of thought, perception, volition, bodily experience and action, and its impact on the basic affective substratum.

Also, only 6.4% of initial ICD-10 schizophrenia cases were later considered schizoaffective (Table 2), perhaps as a manifestation of early-illness fluidity 7–11 and a need for 12–24 months of observation for confident diagnosis of schizophrenia.63,64 In contrast, almost all DSM-IV schizoaffective cases were not diagnosed before 2 years of follow-up.38 Indeed, schizoaffective disorder, as currently conceived in the US, is similar to schizophrenia in severity, chronicity, and disability, high rates of co-morbidity and relatively young onset.14,24 This concept differs sharply from Kasanin’s 61 original concept of acute admixtures of features, and other recent formulations that include both an episodic course 31 and a favorable long-term outcome.22

Comparisons with earlier studies

Several prospective studies considered stability of first-episode psychotic-illness diagnoses, although large, broad samples followed-up for a year or longer,14,18,25,26,30–32,34,35,38 and evaluations of factors associated with diagnostic stability are rare.26,31,32,35,38 Several studies specifically considered longitudinal stability of individual, ICD-10 acute psychotic-disorder diagnoses,39–44 schizophrenia,45,46 mania or severe depression with psychotic features,47–49 but only two 25,28 considered diagnostic stability over time in a broad range of functional psychoses, and neither explored factors predicting stability.25,28

These studies 25,28 averaged with our findings (Table 2) indicated that ICD-10 schizophrenia was a particularly stable initial diagnosis (92.2±9.2%), mania with psychotic symptoms similarly stable (90.8±8.4%), delusional disorder and severe depressive episode with psychotic features less stable (75.4±21.2%), ATPD moderately unstable (63.7±32.6%), and the pool of unspecified acute psychoses even less stable (40.1±24.1% of cases remaining stable for at least one year). Compared with our findings of 100% longitudinal diagnostic stability among initial ICD-10 schizoaffective cases (Table 2), one comparable study found that only 20% of cases initially considered schizoaffective (2.9%) remained so at 36 months,25 and the other did not identify any subject as schizoaffective at baseline or at 12-months.28

Predictive factors

Factors associated with diagnostic instability included any type of Schneiderian FRS 53 at presentation and lack of previous substance-use disorders (Table 4B). Comparable studies are rare, and none used ICD-10 criteria. Schwartz et al.26 found that diagnostic change between 6 and 24 months to DSM-IV schizophrenia or schizoaffective categories was associated with: poor adolescent adjustment, lack of early substance-abuse, psychosis lasting ≥3 months before hospitalization, more initial negative symptoms, prolonged hospitalization, and antipsychotic treatment at discharge. For Schimmelmann et al.31 higher initial global impression (CGI) and lower premorbid functional (GAF) scores predicted shifts from DSM-IV schizophreniform disorder to schizophrenia or schizoaffective diagnoses. Whitty et al.32 associated diagnostic change generally with less education, milder initial DSM-IV psychopathology, and co-morbid substance-abuse. Relationships of substance-use disorders to risk or timing of new psychotic disorder diagnoses remain particularly unclear, as the evidence is inconsistent.26,32,33,65

Subramaniam and colleagues 35 found duration of untreated psychosis to be the only significant predictor of diagnostic shifts towards a DSM-IV “schizophrenia-spectrum.” Fraguas et al.36 reported that diagnostic concordance of 54.2% between baseline and 1-year diagnoses rose to 95.7% by 2-years, highlighting the importance of prolonged follow-up to stable diagnosis. Our previous study 38 with the same 500-patient-sample diagnosed by DSM-IV criteria, found that diagnostic instability was predicted by initial non-affective diagnoses and auditory hallucinations, younger age at syndromal-onset, male sex, and gradual onset.

The finding that Schneiderian FRS predicted diagnostic instability while also representing important anchors for the relatively stable ICD-10 diagnosis of schizophrenia, seems paradoxical. It may be that FRS are also core descriptive features for ATPD, especially its highly unstable subtypes, namely acute schizophrenia-like, and APPD with schizophrenia symptoms. Peter Berner 66 hypothesized that FRS emerging during acute psychosis may represent continuously fluctuating impulses, drives, emotions, feelings, and mood states (the so called “dynamic instability”) that disrupt basic, innate behavioral schemes, ideas, mental images, and personal values (“structural components”). Since specific interactions between dynamic and structural components might facilitate emergence of mainly affective, non-affective, or schizoaffective psychoses, FRS might well be associated with diagnostic changes that reflect the premorbid psychobiological substratum from which psychotic illnesses develop.

Associations of early features with later diagnoses encourage further study of the potential predictive value of early phenomenology,21 to guide earlier diagnosis and therapeutic interventions aimed at limiting morbidity and disability, as well as to limit adverse effects and costs of unnecessary treatments.67,68 However, challenges of evaluating early or premorbid phenomena are great, especially in young patients. Early symptoms can obscure or delay diagnosis of psychotic disorders, particularly when prominent nonspecific features suggest neurotic, personality, conduct, cognitive, or substance-use disorders.14,16,17,21,24,26,33,69–75

Conclusions

Our findings underscore the wide diversity of diagnostic stability among initial ICD-10 psychotic-disorder diagnoses, based on two years of observation from onset. They suggest four major nodes of stability: [a] very high stability (95%–100%) in ICD-10 schizoaffective disorder, mania with psychotic symptoms, mixed affective episode, and schizophrenia > [b] moderately high stability (85%–88%) in delusional disorder and severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms > [c] limited stability (67%) in APPD and unspecified non-organic psychosis ≫ [d] low stability (29%%) of acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder. ICD-10 schizoaffective disorder and mania with psychotic symptoms were particularly stable diagnoses, and somewhat more robust as initial diagnoses than mixed-affective episode, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorders. Early allocation of individual patients to a particular diagnosis or to such diagnostic nodes might usefully consider the details of early psychopathology as well as presenting clinical features, including their timing and plasticity over time.

Most diagnostic changes were to schizoaffective diagnoses, usually anticipated by initial mixed-affective episodes or later-emerging affective components of initially non-affective psychotic illnesses, and typically with unfavorable outcomes. This category challenges the standard psychotic versus affective Kraepelinian dichotomy underlying both DSM-IV and ICD-10, and requires further study. Despite the higher sensitivity and stability of an ICD-10 schizoaffective diagnosis than the corresponding DSM-IV category in this same cohort of 500 patients,38 the diagnosis of schizoaffective disorders in general may require more than 12 months of follow-up, and may include acute and episodic, as well as chronic forms.

In light of the high diagnostic stability of ICD-10 ATPD and its polymorphic subtypes, we also recommend critical re-evaluation of the DSM-IV categories of “schizophreniform,” “brief psychotic” disorders, and related concepts. Developing improved diagnostic criteria for such supposedly good-prognosis and time-limited disorders may require integrating categorical and dimensional approaches, with consideration of early features, type of onset, as well as long-term outcomes.1,76–80 Finally, we specifically encourage continued efforts to devise diagnostic methods and criteria to identify patients with psychotic disorders of favorable course as early as possible, if only to avoid unnecessarily pessimistic prognoses and overuse of antipsychotic medications and other costly or risky interventions.67,81

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from NARSAD (to PS); by NIH grants MH-04844, MH-10948 and a grant from the Atlas Foundation (to MT); by grants MH-47370 and MH-73049, and from the Bruce J. Anderson Foundation, and the McLean Private Donors Research Fund (to RJB); and by the Spanish Ministry of Education & Science and CIBERSAM (to EV). Statistical advice was provided by Theodore Whitfield, D.Sc., and the late John Hennen, Ph.D. Dr. Francesca Stefani provided valuable assistance with data collections in Parma.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Salvatore, Ms. Khalsa, and Drs. Perez Sanchez-Toledo, Zarate and Maggini have no relevant disclosures. Dr. Baldessarini has recently been a consultant or research collaborator with Auritec, Biotrofix, Eli Lilly, IFI, Janssen, JDS-Noven, Luitpold, NeuroHealing, Novartis and Pfizer Corporations, but is not a member of speakers’ bureaus, nor does he or any family member hold equity positions in pharmaceutical or biomedical companies. Dr. Tohen was an employee and stockholder of Eli Lilly & Co to 2008, as is his wife currently. Dr. Vieta consults to or receives research support from Astra-Zeneca, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Eli Lilly, Forrest, Glaxo-SmithKline, Janssen-Cilag, Jazz, Merck, Novartis, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Servier Corporations.

References

- 1.Jaspers K. In: General Psychopathology (1913) Hoenig J, Hamilton MW, editors. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1997. pp. 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kraepelin E. Psychiatrie: Ein Lehrbuch für Studierende und Ärzte (1913) In: Barclay RM, translator. Textbook of Psychiatry for students and physicians. Vol. 1913. Leipzig: JA Barth; Edinburgh: E & S Livingstone; 1919. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robins E, Guze SB. Establishment of diagnostic validity in psychiatric illness: application to schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1970;126:983–997. doi: 10.1176/ajp.126.7.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision (ICD-10): Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: WHO; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Press; 2000. text revision (DSM-IV-TR) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldessarini RJ. American biological psychiatry and psychopharmacology 1944–1994. In: Menninger RW, Nemiah JC, editors. American Psychiatry After World War II (1944–1994) Vol. 16. Washington, DC: APA Press; 2000. pp. 371–412. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fennig S, Kovasznay B, Rich C, et al. Six-month stability of psychiatric diagnoses in first-admission patients with psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1200–1208. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGorry PD. The influence of illness duration on syndrome clarity and stability in functional psychosis: does the diagnosis emerge and stabilize with time? Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 1994;28:607–619. doi: 10.1080/00048679409080784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kramer MD, Krueger RF, Hicks BM. The role of externalizing and internalizing liability factors in accounting for gender differences in the prevalence of common psychopathological syndromes. Psychol Med. 2008;38:51–61. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Werry TS, Taylor E. Schizophrenic and allied disorders. In: Rutter M, Taylor E, Hersov L, editors. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: Modern Approaches. 3. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1994. pp. 594–615. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valevski A, Ratzoni G, Sever J, et al. Stability of diagnosis: 20-year retrospective cohort study of Israeli psychiatric adolescent inpatients. J Adolescence. 2001;24:625–633. doi: 10.1006/jado.2001.0423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kendler KS. Toward a scientific psychiatric nosology: strengths and limitations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:969–973. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810220085011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kendler KS, Walsh D. Structure of psychosis: syndromes and dimensions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:508–509. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.6.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McClellan J, McCurry C. Early onset psychotic disorders: diagnostic stability and clinical characteristics. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;8 (1 Suppl):113–119. doi: 10.1007/pl00010686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollis C. Adult outcomes of child- and adolescent-onset schizophrenia: diagnostic stability and predictive validity. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1652–1659. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peralta V, Cuesta MJ. Can schizophrenia be diagnosed in the initial prodromal phase? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:664–665. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.7.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drake RJ, Dunn G, Tarrier N, et al. Evolution of symptoms in the early course of non-affective psychosis. Schizophrenia Res. 2003;63:171–179. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00334-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarbin H, von Knorring AL. Diagnostic stability in adolescent onset psychotic disorders. Eur Child Adoles Psychiatry. 2003;12:15–22. doi: 10.1007/s00787-003-0300-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peralta V, Cuesta MJ. Nosology of psychotic disorders: comparison among competing classification systems. Schizophrenia Bull. 2003;29:413–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Susser E, Fennig S, Jandorf L, et al. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and course of brief psychoses. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1743–1748. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.12.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh SP, Burns T, Amin S, et al. Acute and transient psychotic disorders: precursors, epidemiology, course and outcome. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:452–459. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.6.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jäger M, Bottlender R, Strauss A, et al. Fifteen-year follow-up of ICD-10 schizoaffective disorders compared with schizophrenia and affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109:30–37. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-690x.2004.00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vollmer-Larsen A, Jacobsen TB, Hemmingsen R, et al. Schizoaffective disorder: reliability of its clinical diagnostic use. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113:402–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McClellan JM, Werry JS, Ham M. Follow-up study of early onset psychosis: comparison between outcome diagnoses of schizophrenia, mood disorders, and personality disorders. J Autism Devel Disord. 1993;23:243–262. doi: 10.1007/BF01046218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amin S, Singh SP, Brewin J, et al. Diagnostic stability of first-episode psychosis: comparison of ICD-10 and DSM-III-R systems. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:537–543. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz JE, Fennig S, Tanenberg-Karant M, et al. Congruence of diagnoses two years after a first-admission diagnosis of psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:593–600. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Veen ND, Selten JP, Schols D, et al. Diagnostic stability in a Dutch psychosis incidence cohort. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:460–464. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.6.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amini H, Alaghband-Rad J, Omid A, et al. Diagnostic stability in patients with first-episode psychosis. Australasian Psychiatry. 2005;13:388–392. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1665.2005.02199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baldwin P, Browne D, Scully PJ, et al. Epidemiology of first-episode psychosis. Schizophrenia Bull. 2005;31:624–638. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rufino AC, Uchida RR, Vilela JA, et al. Stability of the diagnosis of first-episode psychosis made in an emergency setting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:189–193. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schimmelmann BG, Conus P, Edwards J, et al. Diagnostic stability 18 months after treatment initiation for first-episode psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1239–1246. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitty P, Clarke M, McTigue O, et al. Diagnostic stability four years after a first episode of psychosis. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1084–1088. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.9.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caton CL, Hasin DS, Shrout PE, et al. Stability of early-phase primary psychotic disorders with concurrent substance use and substance-induced psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:105–111. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.015784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rahm C, Cullberg J. Diagnostic stability over 3 years in a total group of first-episode psychosis patients. Nord J Psychiatry. 2007;61:189–193. doi: 10.1080/08039480701352454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Subramaniam M, Pek E, Verma S, et al. Diagnostic stability 2 years after treatment initiation in the early psychosis intervention programme in Singapore. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2007;41:495–500. doi: 10.1080/00048670701332276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fraguas D, de Castro MJ, Medina O, et al. Does diagnostic classification of early-onset psychosis change over follow-up? Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2008;39:137–145. doi: 10.1007/s10578-007-0076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tohen M, Zarate CA, Jr, Hennen J, et al. McLean-Harvard First-Episode Mania Study: prediction of recovery and first recurrence. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:2099–2107. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salvatore P, Baldessarini RJ, Tohen M, et al. McLean-Harvard International First-Episode Project: Two-year stability of DSM-IV diagnoses in 500 first-episode psychotic disorder patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:458–466. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jørgensen P, Bennedsen B, Christensen J, et al. Acute and transient psychotic disorder: 1-year follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;96:150–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb09920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sajith SG, Chandrasekaran R, Sadanandan Unni KE, et al. Acute polymorphic psychotic disorder: stability over 3 years. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;105:104–109. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marneros A, Pillmann F, Haring A, et al. What is schizophrenic in acute and transient psychotic disorder? Schizophrenia Bull. 2003;29:311–323. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thangadurai P, Gopalakrishnan R, Kurian S, et al. Diagnostic stability and status of acute and transient psychotic disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:293. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jäger M, Riedel M, Möller HJ. [Acute and transient psychotic disorders (ICD-10: F23). Empirical data and implications for therapy] Nervenärzt. 2007;78:745–752. doi: 10.1007/s00115-006-2211-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Castagnini A, Bertelsen A, Berrios GE. Incidence and diagnostic stability of ICD-10 acute and transient psychotic disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49:255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deister A, Marneros A. Long-term stability of subtypes in schizophrenic disorders: a comparison of four diagnostic systems. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993;242:184–190. doi: 10.1007/BF02189961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Remschmidt H, Martin M, Fleischhaker C, et al. Forty-two years later: the outcome of childhood-onset schizophrenia. J Neural Trans. 2007;114:505–512. doi: 10.1007/s00702-006-0553-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kessing LV. Diagnostic stability in depressive disorder as according to ICD-10 in clinical practice. Psychopathology. 2005;38:32–37. doi: 10.1159/000083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kessing LV. Diagnostic stability in bipolar disorder in clinical practice as according to ICD-10. J Affect Disord. 2005;85:293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baca-Garcia E, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Basurte-Villamor I, et al. Diagnostic stability and evolution of bipolar disorder in clinical practice: prospective cohort study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;115:473–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brill N, Levine SZ, Reichenberg A, Lubin G, et al. Pathways to functional outcomes in schizophrenia: role of premorbid functioning, negative symptoms and intelligence. Schizophr Res. 2009;110:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baldessarini RJ, Finklestein S, Arana GW. Predictive power of diagnostic tests and the effect of prevalence of illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:569–573. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790050095011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schneider K. In: Clinical Psychopathology. Hamilton MW, translator. New York: Grune and Stratton; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Angst J, Sellaro R. Historical perspectives and natural history of bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:445–457. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00909-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-Depressive Illness. 2. New-York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mojtabai R, Susser ES, Bromet EJ. Clinical characteristics, 4-year course, and DSM-IV classification of patients with non-affective acute remitting psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:2108–2115. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Correll CU, Smith CW, Auther AM, et al. Predictors of remission, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder in adolescents with brief psychotic disorder or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified considered at very high risk for schizophrenia. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2008;18:475–490. doi: 10.1089/cap.2007.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marneros A, Pillmann F, Haring A, et al. Is the psychopathology of acute and transient psychotic disorder different from schizophrenic and schizoaffective disorders? Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20:315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pillmann F, Haring A, Balzuweit S, et al. Concordance of acute and transient psychoses and cycloid psychoses. Psychopathology. 2001;34:305–311. doi: 10.1159/000049329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pillmann F, Marneros A. Longitudinal follow-up in acute and transient psychotic disorders and schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;187:286–287. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kasanin J. Acute schizoaffective psychoses (1933) Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151 (6 Suppl):144–154. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.6.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Addington J, Chaves A, Addington D. Diagnostic stability over one year in first-episode psychosis. Schizophrenia Res. 2006;86:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rey ER, Bailer J, Brauer W, et al. Stability trends and longitudinal correlations of negative and positive syndromes within three-year follow-up of initially hospitalized schizophrenics. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;90:405–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reichemberg A, Rieckmann N, Harvey PD. Stability in schizophrenia symptoms over time: findings from the Mount Sinai Pilgrim Psychiatric Center Longitudinal Study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114:363–372. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baethge C, Hennen J, Khalsa HM, et al. Sequencing of substance use and affective morbidity in 166 first-episode bipolar I disorder patients. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:738–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berner P. Delusional atmosphere: Br. J Psychiatry. 1991;14:88–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McGorry PD. Evaluating the importance of reducing the duration of untreated psychosis. Austral NZ J Psychiatry. 2000;34 (Suppl):145–149. doi: 10.1080/000486700236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van Rossum I, Haro JM, Tenback D, et al. Stability and treatment outcome of distinct classes of mania. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23:360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bromet EJ, Naz B, Fochtmann LJ, et al. Long-term diagnostic stability and outcome in recent first-episode cohort studies of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull. 2005;31:639–649. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fennig S, Bromet EJ, Craig T, et al. Psychotic patients with unclear diagnoses: descriptive analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183:207–213. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199504000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Klosterkötter J, Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, et al. The European Prediction of Psychosis Study (EPOS): integrating early recognition and intervention in Europe. World Psychiatry. 2005;4:161–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Addington J, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, et al. North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study: a collaborative multisite approach to prodromal schizophrenia research. Schizophrenia Bull. 2007;33:665–672. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Picker H, et al. Basic symptoms in early psychotic and depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;51 (Suppl):31–37. doi: 10.1192/bjp.191.51.s31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, et al. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:28–37. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nelson B, Yung AR, Bechdolf A, et al. Phenomenological critique and self-disturbance: implications for ultra-high risk (“prodrome”) research. Schizophrenia Bull. 2008;34:381–392. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Peralta V, Cuesta MJ. Underlying structure of diagnostic systems of schizophrenia: comprehensive polydiagnostic approach. Schizophrenia Res. 2005;79:217–219. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Allardyce J, Suppes T, Van Os J. Dimensions and the psychosis phenotype. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2007;16 (Suppl 1):S34–S40. doi: 10.1002/mpr.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Häfner H. [Is the schizophrenia diagnosis still appropriate?] Psychiatr Prax. 2007;34:175–180. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-952032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vieta E, Phillips ML. Deconstructing bipolar disorder: critical review of its diagnostic validity and a proposal for DSM-V and ICD-11. Schizophrenia Bull. 2007;33:886–892. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Krueger RF, Markon KE. Understanding Psychopathology: melding behavior genetics, personality, and quantitative psychology to develop an empirically based model. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2008;15:113–117. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2006.00418.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Leonhard K. In: Classification of Endogenous Psychoses and their Differentiated Etiology. 2. Beckmann H, editor. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1999. [Google Scholar]