Abstract

Background

Pre-menstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is commonly studied in white women; consequently, it is unclear whether the prevalence of PMDD varies by race. Although a substantial proportion of black women report symptoms of PMDD, the Biocultural Model of Women’s Health and research on other psychiatric disorders suggest that black women may be less likely than white women to experience PMDD in their lifetimes.

Method

Multivariate multinomial logistic regression modeling was used with a sample of 2590 English-speaking, pre-menopausal American women (aged 18–40 years) who participated in the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys in 2001–2003. The sample consisted of 1672 black women and 918 white women. The measure of PMDD yields a provisional diagnosis of PMDD consistent with DSM-IV criteria.

Results

Black women were significantly less likely than white women to experience PMDD [odds ratio (OR) 0.44, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.25–0.79] and pre-menstrual symptoms (OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.47–0.88) in their lifetimes, independently of marital status, employment status, educational attainment, smoking status, body mass index, history of oral contraceptive use, current age, income, history of past-month mood disorder, and a measure of social desirability. The prevalence of PMDD was 2.9% among black women and 4.4% among white women.

Conclusions

This study showed for the first time that black women were less likely than white women to experience PMDD and pre-menstrual symptoms, independently of relevant biological, social-contextual and psychological risk factors. This suggests that PMDD may be an exception to the usual direction of racial disparities in health. Further research is needed to determine the mechanisms that explain this health advantage.

Keywords: Epidemiology, minority health, premenstrual dysphoric disorder

Introduction

Pre-menstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), a psychiatric diagnosis included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV; APA, 1994), affects approximately 6% of women in the community (Cohen et al. 2002; Wittchen et al. 2002), and is characterized by severe affective and somatic symptoms that occur in the days preceding the onset of menses (APA, 1994). Most of these data are drawn from white participants; consequently, the potentially unique experiences of ethnic minority women are unexplored.

Studies of Nigerian university students document the presence of PMDD among a substantial proportion of black women (Adewuya et al. 2008; Issa et al. 2010). However, epidemiological investigations in the USA have included only a small percentage of blacks (Rivera-Tovar & Frank, 1990; Cohen et al. 2002; Gehlert et al. 2009), which precludes the estimation of PMDD prevalence among American black women. According to the United States Census projections, the black population will more than double in size by 2050 and comprise 16% of the total population (Day, 1996). Consequently, black women will soon represent a large segment of the female population at risk for PMDD. Since little is known about the occurrence of PMDD in this population, the Office for Women’s Health Research identified the examination of PMDD among black women as a research priority (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999).

While a substantial proportion of black women will experience PMDD in their lifetimes, they may be less likely than white women to experience PMDD for several reasons. First, blacks are consistently less likely than whites to suffer from other psychiatric disorders, including mood, anxiety and substance-abuse disorders (Breslau et al. 2005; Tiwari & Wang, 2006; Williams et al. 2007). Out of four studies, two demonstrated that blacks were significantly less likely than whites to report pre-menstrual symptoms (Deuster et al. 1999; Sternfeld et al. 2002; Masho et al. 2005; Gold et al. 2007). To our knowledge, race differences in PMDD have not been documented in the existing literature.

Second, the Biocultural Model of Women’s Health (Melby et al. 2005) implicates culture as a major determinant of health and illness (in addition to biological, psychological and social-contextual factors). This perspective has been particularly relevant in the field of menopausal research, where studies have demonstrated that the type and frequency of menopausal symptoms vary among different racial and ethnic groups (Avis et al. 2001). Moreover, culture is associated with attitudes toward menopausal symptoms and perceptions of impairment. Blacks generally espouse more positive attitudes toward menopause than whites (Standing & Glazer, 1992; Pham et al. 1997), and do not see their symptoms as impairing or disruptive to their functioning (Im et al. 2010a, b).

If the patterns observed with respect to menopausal symptoms are also true of PMDD, these culturally determined views could contribute to lower rates of PMDD in blacks, compared with whites. For example, in Western culture menstruation is overwhelmingly viewed as an aversive event (Figert, 2005); these negative expectations and attitudes are hypothesized to contribute to the perception and severity of PMDD symptoms among Western women. Blechman (1988) suggested that white women, in contrast to ethnic minority women, may be more vigilant for indicators of the onset of the aversive event, menses, and thus more likely to construe pre-menstrual changes negatively in accordance with Western cultural beliefs. In support of this explanation, a British study of white, Asian and Afro-Caribbean women showed significantly higher rates of pre-menstrual symptom reporting among white women (van den Akker et al. 1995). Researchers hypothesized that greater attention to pre-menstrual symptoms increased white women’s anxiety, depression and stress, further exacerbating pre-menstrual changes in this population. In contrast to whites, Asian and Afro-Caribbean women were less influenced by Western attitudes toward menstruation, and subsequently perceived pre-menstrual changes to be less distressing (van den Akker et al. 1995).

Third, the Biocultural Model of Women’s Health suggests that the socio-contextual qualities specific to black culture may buffer against the negative health effects of chronic and acute stress, which have been implicated in the etiology of PMDD and premenstrual symptoms (Beck et al. 1990; Warner & Bancroft, 1990; Fontana & Palfai, 1994; Golding et al. 2000; Hourani et al. 2004; Perkonigg et al. 2004). The extensive social support networks and protective aspects of ethnic identity that characterize black culture (Sellers et al. 2003; Clay et al. 2008) may buffer the deleterious health impact of stress. Several studies have demonstrated that the presence of these factors is negatively associated with the prevalence of other psychiatric disorders among black women (Clay et al. 2008; Almeida et al. 2010). In addition, black women may relieve stress through spirituality and participation in religious activities, outlets that are more prevalent in this population compared with other ethnic groups (Taylor et al. 2007). Evidence from the menopausal literature supports this explanation; a black participant in a qualitative study on menopause noted, ‘As African American women [… y]ou just take life as it comes and do what you have to do. If you are having troubles or problems, you should just pray about it and keep going’ (Im et al. 2010a). Since spirituality and religious participation are associated with better mental health outcomes in the black community (Levin et al. 1995; van Olphen et al. 2003; Moreira-Almeida et al. 2006), these practices may also contribute to lower rates of PMDD among black women.

In conclusion, the consistent black–white differences in the prevalence of other psychiatric disorders, evidence demonstrating that blacks were less likely than whites to report experiencing pre-menstrual symptoms, and the cultural and social-contextual mechanisms suggested by the Biocultural Model of Women’s Health, led us to hypothesize that the prevalence of PMDD and pre-menstrual symptoms would be significantly lower among black women, compared with white women.

Method

Participants

The women in our study participated in two of the National Institutes of Health-funded Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES): the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R; Kessler & Merikangas, 2004), which oversampled black participants, and the National Survey of American Life (NSAL; Jackson et al. 2004), which was composed almost entirely of black participants. Data from the NCS-R and NSAL may be analysed as a single large sample population using weighting variables calculated by the survey designers (Heeringa et al. 2004). The CPES include English-speaking, non-institutionalized adults (aged ≥18 years). Respondents were 1742 C. E. Pilver et al. selected for inclusion in the CPES through a multistage probability sampling strategy to achieve nationally representative samples and adequate numbers of racial/ethnic minorities. Respondents were sampled from 252 primary sampling units in the contiguous USA. English language proficiency was a requirement for inclusion for the NSC-R and the NSAL. Participants were provided with a letter explaining the purpose of the survey prior to the interview (Kessler et al. 2004). Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were told that they would be participating in a survey about ‘people’s health and health issues’ (Pennell et al. 2004). Interviews were conducted in person or by telephone (when requested) from 2001 to 2003 by extensively trained lay interviewers who utilized computer-assisted interviewing techniques; response rates ranged from 71% to 81% (Pennell et al. 2004). The details of survey methodology have been described at length elsewhere (Heeringa et al. 2004; Pennell et al. 2004).

Inclusion criteria for our study were as follows: self-identified as black or white; completed the PMDD module; reported having regular periods; and between the ages of 18 and 40 years to increase the possibility that women were pre-menopausal and not yet peri-menopausal. From 8939 female participants in the NCS-R and NSAL, we excluded 860 women who did not self-identify as black or white. We then excluded 1547 women from the NCS-R1,† and 519 white women from the NSAL who did not receive the PMDD module to reduce study costs. A total of 213 women who did not provide valid data to determine their PMDD case status were also excluded; race was not significantly associated with missing PMDD case status. We excluded 2093 post-menopausal women, 221 women whose periods had stopped temporarily for reasons other than pregnancy (e.g. the possible onset of menopause or dieting), and nine women who did not indicate whether they continued to have monthly periods. We then excluded 887 women who were older than age 40 years. Our final sample included 2590 participants.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of our sample. The majority of our sample is Caucasian (80.6%), employed (73.7%), well-educated (11.7% with less than high school education), married (49.0%), never smokers (58.3%) and current or former users of birth control (80.2%). Only 5.0% of participants had a DSM-IV diagnosed mood disorder in the past month. The average age of the sample was 28.9 years (S.E.=0.30, range 18–40) years. The average participant had a household income over four times the poverty threshold for their household size (mean=4.6, S.E.=0.14, range 0–17). The rate of missing data was very low in the sample (<1% for most covariates) and not significantly associated with race.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study participants

| Sample characteristics | na (%b) |

|---|---|

| Race | |

| Black | 1672 (19.45) |

| White | 918 (80.55) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 1898 (73.72) |

| Unemployed | 261 (5.19) |

| Not in labor force | 428 (21.09) |

| Educational attainment | |

| Less than high school | 395 (11.71) |

| High school graduate | 839 (27.67) |

| Some college | 818 (35.17) |

| College or above | 538 (25.46) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 1035 (49.01) |

| Previously married | 374 (10.33) |

| Never married | 1181 (40.65) |

| Smoking status | |

| Current | 615 (26.84) |

| Former | 267 (14.82) |

| Never | 1707 (58.34) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | |

| <18.5 | 82 (5.13) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 1027 (51.91) |

| >25 | 1398 (42.96) |

| Mood disorder | |

| Yes | 141 (5.00) |

| No | 2449 (95.00) |

| History of oral contraceptive use | |

| Ever user | 2018 (80.20) |

| Never user | 572 (19.80) |

| Mean age, years (standard error) | 28.85 (0.30) |

| Mean income (standard error) | 4.60 (0.14) |

n=2590, numbers may not sum to total because of missing data.

Weighted %.

Measures

The CPES utilized a modified version of the World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI), version 3.0 (Pennell et al. 2004). Individual survey modules contained questions that correspond to the DSM-IV criteria, and diagnostic algorithms developed by the survey designers yield valid and reliable diagnoses of Axis I disorders (Kessler & Ustün, 2004; Pennell et al. 2004). The WMH-CIDI also includes modules for demographic cultural, and health information.

Predictor variable

‘Race’ is a two-level nominal variable constructed from the question ‘How would you describe your race/ancestry?’ Afro-Caribbean and African American respondents were classified as blacks and Non-Latina white respondents were classified as whites.

Dependent variable

‘PMDD status’ is the dependent variable in our analysis with three mutually exclusive levels of response: PMDD, pre-menstrual symptoms, and the absence of pre-menstrual symptoms.

The lifetime prevalence of PMDD was assessed with the WMH-CIDI ‘Premenstrual Syndrome’ module, which is based on DSM-IV criteria for PMDD (APA, 1994). Before starting the Premenstrual Syndrome module, women were told ‘This part of the interview is about women’s health issues’ (WHO, 1990). Women who met the case definition for PMDD reported (1) experiencing depressed mood, anxiety or irritability in the week prior to her period (2) in at least seven of 12 menstrual cycles at the point in her life when symptoms were at their worst, (3) that these mood changes were worse than normal most of the time, (4) and symptoms such as difficulty concentrating, tiredness, change in appetite or change in sleep were present. She also had to report (5) interference in work, social life or personal relationships, or (6) impairment in daily activities because of these problems. Women with pre-menstrual symptoms had at least one of the first four symptoms but did not meet the case definition for PMDD. Women without symptoms were categorized as having an absence of symptoms.

Covariates

We included correlates of pre-menstrual symptoms and PMDD (Deuster et al. 1999; Cohen et al. 2002; Halbreich et al. 2003) as well as factors suggested by the Biocultural Model of Women’s Health (Melby et al. 2005). These include smoking status (current smoker, ex-smoker, or never smoker), current age (range 18–59 years), body mass index (BMI <18.5, 18.5–24.9, ≥25 kg/m2), history of oral contraceptive use (never users or ever users), marital status (married, previously married, never married), employment status (employed, not employed, or not in the labor force), educational attainment (less than high school, high school diploma, some college, or college and above), income (range 0–18; this value is calculated by dividing the total family income by the poverty threshold for a family of that size; US Census Bureau, 2009), and diagnosis of a mood disorder in the past-month (yes or no; includes bipolar depression dysthymia, hypomania, major depressive disorder, major depressive episode, and mania). We also controlled for socially desirable reporting using a 10-item scale developed by Crowne & Marlowe (range 0–10) (Crowne & Marlowe, 1960).

Statistical analysis

Data management and selected model diagnostics were completed with SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., USA). SUDAAN utilized Taylor series linearization procedures (Research Triangle Institute, USA) to account for the clustering and weighting of the CPES survey data. The appropriate CPES weighting variable was included in all analyses.

Using SUDAAN procedures, we produced weighted, unadjusted prevalence estimates for PMDD status. First, we evaluated the bivariate relationships between PMDD status, race and control covariates. The Wald χ2 test and Wald F test were used to evaluate the statistical significance of associations between categorical and continuous variables, respectively. We then constructed unadjusted and multivariate-adjusted multinomial logistic regression models for hypothesis testing. The predictor variable and the covariates entered the adjusted model in a single step. The Wald χ2 test was used to evaluate the general association between the independent variables and PMDD status. The statistical significance of individual parameter estimates was evaluated with two-sided t tests.

We evaluated the fit and assumptions of our multinomial regression models using several statistical techniques (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2006). We adjusted for multiple comparisons using Benjamini and Hochberg’s false discovery rate formula (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995).

Results

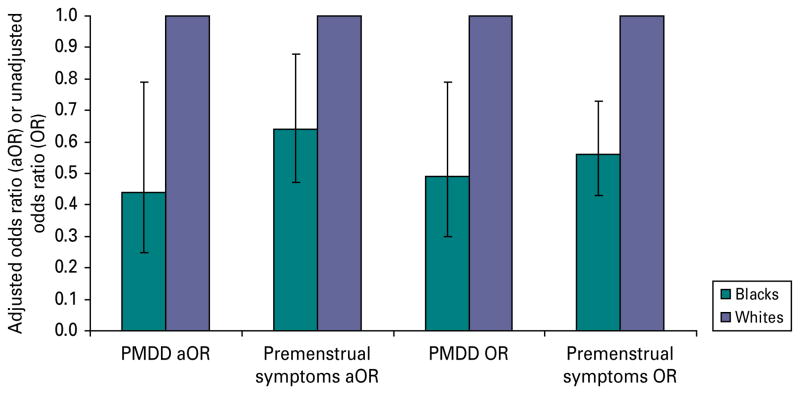

The lifetime prevalence of PMDD was 4.1% in our sample. The lifetime prevalence of PMDD was greater among whites (4.4%) compared with blacks (2.9%). Similarly, the lifetime prevalence of any pre-menstrual symptoms was also greater among whites (56.0%) compared with blacks (43.0%). As predicted, the overall relationship between race and PMDD status was statistically significant in unadjusted (p<0.001) and adjusted (p<0.001) multinomial logistic regression analysis. Blacks were significantly less likely than whites to experience PMDD [odds ratio (OR) 0.44, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.25–0.79] and pre-menstrual symptoms (OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.47–0.88) in their 1744 C. E. Pilver et al. lifetimes after statistical control for employment status, educational attainment, marital status, smoking status, oral contraceptive use, BMI, diagnosis of a mood disorder, current age, income and social desirability (Fig. 1). To explore the contribution of these demographic variables, we compared the unadjusted parameter estimates with the adjusted parameter estimates for race. The unadjusted and adjusted parameter estimates were very similar (adjusted OR – unadjusted OR/unadjusted OR <15%), indicating that these demographic factors were not confounding the relationship between race and PMDD status.

Fig. 1.

Pre-menstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) and pre-menstrual symptoms in black compared to white women. We statistically controlled for race/ethnicity, marital status, employment status, educational attainment, smoking status, body mass index, oral contraceptive use, current age, income, past month mood disorder and social desirability in the multivariate-adjusted multinomial logistic regression model. Bar values are adjusted odds ratios (aOR) or unadjusted odds ratios (OR), with 95% confidence intervals represented by error bars.

Educational attainment, smoking status, history of oral contraceptive use, marital status, BMI, income and age were significantly associated with either PMDD status (Table 2) or race in bivariate analyses (Table 3) and were thus included in covariates in all multivariate analyses. Regression diagnostics revealed no problems with model assumptions or fit.

Table 2.

Bivariate associations between study characteristics and PMDD status

| Sample characteristics | No symptoms | Pre-menstrual symptoms | PMDD | pc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racea | <0.001 | |||

| Black | 920 (24.79) | 699 (15.64) | 53 (13.84) | |

| White | 323 (75.21) | 538 (84.36) | 57 (86.16) | |

| Employment statusa | 0.371 | |||

| Employed | 896 (69.95) | 927 (76.70) | 75 (73.36) | |

| Unemployed | 137 (5.67) | 113 (4.70) | 11 (6.71) | |

| Not in labor force | 207 (24.38) | 197 (18.61) | 24 (19.93) | |

| Educational attainmenta | 0.002 | |||

| Less than high school | 212 (13.43) | 165 (10.25) | 18 (12.75) | |

| High school graduate | 437 (29.43) | 370 (25.89) | 32 (32.57) | |

| Some college | 371 (38.15) | 409 (33.29) | 38 (28.81) | |

| College or above | 223 (18.98) | 293 (30.57) | 22 (25.87) | |

| Marital statusa | 0.088 | |||

| Married | 458 (45.73) | 530 (51.64) | 47 (48.90) | |

| Previously married | 178 (8.44) | 176 (11.31) | 20 (17.28) | |

| Never married | 607 (45.84) | 531 (37.06) | 43 (33.82) | |

| Smoking statusa | 0.048 | |||

| Current | 233 (23.82) | 338 (28.25) | 44 (39.79) | |

| Former | 104 (13.04) | 145 (16.28) | 18 (14.32) | |

| Never | 905 (63.15) | 754 (55.47) | 48 (45.88) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2a | 0.202 | |||

| <18.5 | 28 (4.46) | 51 (5.82) | 3 (2.97) | |

| 18.5–24.9 | 447 (49.49) | 507 (54.54) | 43 (42.63) | |

| >25 | 689 (46.05) | 647 (39.64) | 62 (54.40) | |

| Mood disordera | 0.082 | |||

| Yes | 51 (4.00) | 74 (5.33) | 16 (11.04) | |

| No | 1192 (96.00) | 1163 (94.67) | 94 (88.96) | |

| History of oral contraceptive usea | <0.001 | |||

| Ever user | 924 (75.54) | 995 (82.91) | 99 (93.28) | |

| Never user | 319 (24.46) | 242 (17.09) | 11 (6.72) | |

| Mean age, years (standard error)b | 27.79 (0.42) | 29.58 (0.40) | 30.25 (0.87) | 0.002 |

| Mean income (standard error)b | 4.30 (0.16) | 4.84 (0.20) | 4.63 (0.35) | 0.053 |

PMDD, Pre-menstrual dysphoric disorder.

n and % (weighted) for categorical variables, n=2590. Numbers may not sum to total due to missing data.

Continuous variables.

p Value is for Wald χ2 for categorical variables and Wald F test for continuous variables.

Table 3.

Bivariate associations between study characteristics and race

| Sample characteristic | Black | White | pc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employment statusa | <0.001 | ||

| Employed | 1225 (71.75) | 673 (74.20) | |

| Unemployed | 208 (12.36) | 53 (3.45) | |

| Not in labor force | 237 (15.89) | 191 (22.35) | |

| Educational attainmenta | <0.001 | ||

| Less than high school | 307 (20.06) | 88 (9.69) | |

| High school graduate | 602 (37.75) | 237 (25.24) | |

| Some college | 495 (29.12) | 323 (36.63) | |

| College or above | 268 (13.07) | 270 (28.45) | |

| Marital statusa | <0.001 | ||

| Married | 519 (33.02) | 516 (52.88) | |

| Previously married | 264 (13.59) | 110 (9.55) | |

| Never married | 889 (53.39) | 292 (37.58) | |

| Smoking statusa | <0.001 | ||

| Current | 308 (20.17) | 307 (28.45) | |

| Former | 108 (6.62) | 159 (16.80) | |

| Never | 1255 (73.21) | 452 (54.75) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2a | <0.001 | ||

| <18.5 | 38 (3.37) | 44 (5.54) | |

| 18.5–24.9 | 545 (35.16) | 482 (55.88) | |

| >25 | 1020 (61.47) | 378 (35.58) | |

| Mood disordera | 0.142 | ||

| Yes | 73 (3.90) | 68 (5.26) | |

| No | 1599 (96.10) | 850 (94.74) | |

| History of oral contraceptive usea | 0.200 | ||

| Ever user | 1258 (77.79) | 760 (80.79) | |

| Never user | 414 (22.21) | 158 (19.21) | |

| Mean age, years (standard error)b | 28.76 (0.26) | 28.87 (0.36) | 0.799 |

| Mean income (standard error)b | 3.22 (0.08) | 4.94 (0.19) | <0.001 |

n and % (weighted) for categorical variables, n=2590. Numbers may not sum to total due to missing data.

Continuous variables.

p Value is for Wald χ2 for categorical variables and Wald F test for continuous variables.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that black women were significantly less likely than white women to experience PMDD in their lifetimes. The effects of employment status, educational attainment, smoking status, oral contraceptive use, BMI, current age, income, diagnosis of a mood disorder and social desirability on PMDD status were statistically controlled for in order to obtain the independent effect of race in multivariate regression analysis. In addition to our main findings with respect to PMDD, we also found that the lifetime prevalence of pre-menstrual symptoms was significantly lower among blacks, compared with whites. These results supported our hypothesis, and extend prior findings that blacks are at lower risk for other psychiatric disorders, compared with whites.

We adopted several methodological approaches to go beyond prior PMDD research. First, we explicitly examined racial patterns in the lifetime prevalence of PMDD using a large nationally representative population sample. No studies of American women have comprehensively examined whether black women experience PMDD differently from white women. Second, we applied the Biocultural Model of Women’s Health as a theoretical framework to guide our covariate selection for multivariate analyses. Few studies have adopted multivariate approaches, and those that have often failed to properly control for many of the established risk factors for PMDD. Furthermore, the Biocultural Model of Women’s Health suggested a wider range of covariates from the biological, social-contextual and psychological spheres than have been previously considered in a single study.

Third, our study sample, from the CPES, was a randomly selected, nationally representative population sample with adequate numbers of black participants. The results from this general population sample are more readily generalizable than those from many previous studies of American women, which utilized small, racially homogeneous samples (Cohen et al. 2002), convenience samples (Fontana & Palfai, 1994) or were inadequately sized for racial comparisons (Gehlert et al. 2009). The oversampling of minorities in the CPES made it uniquely suited for our analysis. To our knowledge, PMDD has not been analysed in the CPES prior to this investigation.

Fourth, we utilized an accepted measure of PMDD that is consistent with DSM-IV diagnostic criteria and has been successfully applied in multiple studies (Stein et al. 2002; Wittchen et al. 2002; Pezawas et al. 2003; Perkonigg et al. 2004). Fifth, we took several steps to minimize the possibility of reporting bias. For instance, the study sample was restricted to pre-menopausal women who reported having regular menstrual cycles. Consequently, memories of current or recent pre-menstrual symptoms were likely to be more readily accessible. Furthermore, with the relatively young age of this sample (age 18–40 years) it was also unlikely that participants were experiencing menopausal symptoms which they might have misreported as pre-menstrual symptoms. We also controlled for the presence of a DSM-IV diagnosed mood disorder in the past month to adjust for the possible influence of current mental states on symptom reporting. Finally, we used the Crowne–Marlowe scale to control for the reporting of socially desirable responses, ensuring that our observed effects were, in fact, attributable to race. The inclusion of this measure was a unique strength of our study, as no other examinations of PMDD have controlled for social desirability bias.

These findings must be considered in the context of design issues of the CPES. First, a traditional drawback of the cross-sectional design of the CPES is that exposures and outcomes are measured at the same point in time, making temporality difficult to establish. However, temporality was not a concern in this analysis because the predictor variable, race, was a fixed exposure that preceded disease development.

A second limitation of the CPES was that the survey instrument, the WMH-CIDI, assessed PMDD with retrospective symptom reporting. According to the DSM-IV, a diagnosis of PMDD must be considered provisional if it was based on retrospective reports, rather than being confirmed with prospective reports over two consecutive symptomatic menstrual cycles. Daily ratings of pre-menstrual symptoms would be more desirable from a methodological standpoint but would have been extremely burdensome with such a large sample, leaving retrospective reports as the only viable option. Future research should employ both retrospective and prospective measures. Despite its provisional diagnosis, the WMH-CIDI module has successfully produced population prevalence estimates of PMDD (Stein et al. 2002; Wittchen et al. 2002; Pezawas et al. 2003; Perkonigg et al. 2004) in several studies, and its content corresponds to the PMDD diagnostic criteria outlined in DSM-IV.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that black women were significantly less likely than white women to experience PMDD in their lifetimes. For many health outcomes blacks are at a disadvantage compared with whites. Our study suggested the opposite: black women may have an advantage. Future research should aim to identify the factors that may contribute to this advantage, and determine if the nature of this association is a causal one. Potential mechanisms, according to our theoretical model, may be cultural, as well as biological and psychological. If causal mechanisms are identified that are modifiable and applicable to women regardless of their race, this research would provide a basis for developing interventions and treatments for a condition that has an impact on millions of American women.

Acknowledgments

The authors recognize Dr Haiqun Lin, Dr Kimberly Ann Yonkers, Dr Jhumka Gupta and Dr Elizabeth Bertone-Johnson for providing helpful feedback on drafts of this paper. This research was funded by the National Institute on Aging grant 5 T32 AG000153.

Footnotes

The notes appear after the main text.

The NCS-R survey was administered in two parts. Part 1 was given to all 9282 participants, and included the core diagnostic assessment. Part 2, which contained the Premenstrual Syndrome module, was administered to only 5692 participants. This was done to reduce respondent burden and minimize study costs. Participants diagnosed with a threshold or subthreshold disorder in part 1, as well as a probability sample of persons without a psychiatric disorder, completed part 2 of the survey (Kessler et al. 2004).

Declaration of Interest

None.

References

- Adewuya A, Loto O, Adewumi T. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder amongst Nigerian university students: prevalence, comorbid conditions, and correlates. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2008;11:13–18. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0213-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida J, Subramanian SV, Kawachi I, Molnar BE. Is blood thicker than water? Social support, depression and the modifying role of ethnicity/nativity status. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2010 doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.092213. Published online: 7 July 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Avis N, Stellato R, Crawford S, Bromberger J, Ganz P, Cain V, Kagawa-Singer M. Is there a menopausal syndrome? Menopausal status and symptoms across racial/ethnic groups. Social Science and Medicine. 2001;52:345–356. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck L, Gevirtz R, Mortola J. The predictive role of psychosocial stress on symptom severity in premenstrual syndrome. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1990;52:536–543. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199009000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Blechman EA. The premenstrual experience. In: Blechman EA, Brownell KD, editors. Handbook of Behavioural Medicine for Women. Pergamon; New York: 1988. pp. 80–91. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Kendler K, Su M, Gaxiola-Aguilar S, Kessler R. Lifetime risk and persistence of psychiatric disorders across ethnic groups in the United States. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:317–327. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay O, Roth D, Wadley V, Haley W. Changes in social support and their impact on psychosocial outcome over a 5-year period for African American and White dementia caregivers. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;23:857–862. doi: 10.1002/gps.1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L, Soares C, Otto M, Sweeney B, Liberman R, Harlow B. Prevalence and predictors of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) in older premenopausal women. The Harvard Study of Moods and Cycles. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2002;70:125–132. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00458-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowne DP, Marlowe D. A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1960;24:349–354. doi: 10.1037/h0047358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JC. US Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports, P25–1130. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1996. Population projections of the United States by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin: 1995 to 2050; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Deuster P, Adera T, South-Paul J. Biological, social, and behavioral factors associated with premenstrual syndrome. Archives of Family Medicine. 1999;8:122–128. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figert A. Premenstrual syndrome as scientific and cultural artifact. Integrated Physiological and Behavioral Science. 2005;40:102–113. doi: 10.1007/BF02734245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana A, Palfai T. Psychosocial factors in premenstrual dysphoria: stressors, appraisal, and coping processes. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1994;38:557–567. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehlert S, Song I, Chang C, Hartlage S. The prevalence of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in a randomly selected group of urban and rural women. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:129–136. doi: 10.1017/S003329170800322X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold E, Bair Y, Block G, Greendale G, Harlow S, Johnson S, Kravitz H, Rasor M, Siddiqui A, Sternfeld B, Utts J, Zhang G. Diet and lifestyle factors associated with premenstrual symptoms in a racially diverse community sample: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Journal of Women’s Health (Larchmont) 2007;16:641–656. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding J, Taylor D, Menard L, King M. Prevalence of sexual abuse history in a sample of women seeking treatment for premenstrual syndrome. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;21:69–80. doi: 10.3109/01674820009075612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbreich U, Borenstein J, Pearlstein T, Kahn L. The prevalence, impairment, impact, and burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMS/PMDD) Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28 (Suppl 3):1–23. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa S, Wagner J, Torres M, Duan N, Adams T, Berglund P. Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:221–240. doi: 10.1002/mpr.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hourani L, Yuan H, Bray R. Psychosocial and lifestyle correlates of premenstrual symptoms among military women. Journal of Women’s Health (Larchmont) 2004;13:812–821. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2004.13.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im E, Lee B, Chee W, Dormire S, Brown A. A national multiethnic online forum study on menopausal symptom experience. Nursing Research. 2010a;59:26–33. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181c3bd69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im E, Lee S, Chee W. Black women in menopausal transition. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2010b;39:435–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2010.01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa B, Yussuf A, Olatinwo A, Ighodalo M. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder among medical students of a Nigerian university. Annals of African Medicine. 2010;9:118–122. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.68354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J, Torres M, Caldwell C, Neighbors H, Nesse R, Taylor R, Trierweiler S, Williams D. The National Survey of American Life: a study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:196–207. doi: 10.1002/mpr.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Berglund P, Chiu W, Demler O, Heeringa S, Hiripi E, Jin R, Pennell B, Walters E, Zaslavsky A, Zheng H. The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:69–92. doi: 10.1002/mpr.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Merikangas K. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): background and aims. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:60–68. doi: 10.1002/mpr.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Ustün T. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin J, Chatters L, Taylor R. Religious effects on health status and life satisfaction among black Americans. Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1995;50:S154–S163. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.3.s154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masho S, Adera T, South-Paul J. Obesity as a risk factor for premenstrual syndrome. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005;26:33–39. doi: 10.1080/01443610400023049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melby M, Lock M, Kaufert P. Culture and symptom reporting at menopause. Human Reproduction Update. 2005;11:495–512. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmi018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira-Almeida A, Neto F, Koenig H. Religiousness and mental health: a review. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 2006;28:242–250. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462006000300018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennell B, Bowers A, Carr D, Chardoul S, Cheung G, Dinkelmann K, Gebler N, Hansen S, Pennell S, Torres M. The development and implementation of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, the National Survey of American Life, and the National Latino and Asian American Survey. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:241–269. doi: 10.1002/mpr.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkonigg A, Yonkers K, Pfister H, Lieb R, Wittchen H. Risk factors for premenstrual dysphoric disorder in a community sample of young women: the role of traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:1314–1322. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezawas L, Wittchen H, Pfister H, Angst J, Lieb R, Kasper S. Recurrent brief depressive disorder reinvestigated: a community sample of adolescents and young adults. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33:407–418. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham K, Grisso J, Freeman E. Ovarian aging and hormone replacement therapy. Hormonal levels, symptoms, and attitudes of African-American and white women. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997;12:230–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.012004230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Tovar A, Frank E. Late luteal phase dysphoric disorder in young women. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147:1634–1636. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.12.1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers R, Caldwell C, Schmeelk-Cone K, Zimmerman M. Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:302–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standing T, Glazer G. Attitudes of low-income clinic patients toward menopause. Health Care For Women International. 1992;13:271–280. doi: 10.1080/07399339209516002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein M, Höfler M, Perkonigg A, Lieb R, Pfister H, Maercker A, Wittchen H. Patterns of incidence and psychiatric risk factors for traumatic events. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2002;11:143–153. doi: 10.1002/mpr.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternfeld B, Swindle R, Chawla A, Long S, Kennedy S. Severity of premenstrual symptoms in a health maintenance organization population. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;99:1014–1024. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)01958-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick B, Fidell L. Using Multivariate Statistics. Allyn & Bacon; Boston, MA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R, Chatters L, Jackson J. Religious and spiritual involvement among older African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: findings from the National Survey of American Life. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2007;62:S238–S250. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.4.s238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari S, Wang J. The epidemiology of mental and substance use-related disorders among white, Chinese, and other Asian populations in Canada. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;51:904–912. doi: 10.1177/070674370605101406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. [Accessed 10 November 2010];How the Census Bureau measures poverty. 2009 ( http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/about/overview/measure.html)

- US Department of Health and Human Services; US Public Health Service. Executive Summary. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity. US Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- van den Akker O, Eves F, Service S, Lennon B. Menstrual cycle symptom reporting in three British ethnic groups. Social Science and Medicine. 1995;40:1417–1423. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00265-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Olphen J, Schulz A, Israel B, Chatters L, Klem L, Parker E, Williams D. Religious involvement, social support, and health among African-American women on the east side of Detroit. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18:549–557. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21031.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner P, Bancroft J. Factors related to self-reporting of the pre-menstrual syndrome. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;157:249–260. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Composite International Diagnostic Interview. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Williams D, González H, Neighbors H, Nesse R, Abelson J, Sweetman J, Jackson J. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:305–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H, Becker E, Lieb R, Krause P. Prevalence, incidence and stability of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in the community. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:119–132. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]