Abstract

Neuropathic pain in animals results in increased IL-1β expression in the damaged nerve, the dorsal root ganglia, and the spinal cord. Here, we discuss our results showing that this cytokine is also overexpressed at supraspinal brain regions, in particular in the contralateral side of the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex and in the brainstem, in rats with neuropathic pain-like behavior. We show that neuropathic pain degree and development depend on the specific nerve injury model and rat strain studied, and that there is a correlation between hippocampal IL-1β expression and tactile sensitivity. Furthermore, the correlations between hippocampal IL-1β and IL-1ra or IL-6 observed in control animals, are disrupted in rats with increased pain sensitivity. The lateralization of increased cytokine expression indicates that this alteration may reflect nociception. The potential functional consequences of increased IL-1β expression in the brain during neuropathic pain are discussed.

Keywords: chronic pain, Interleukin-1, hippocampus, lateralization

Introduction

According to the American Academy of Pain Medicine,1 seven- and fourfold more Americans suffer from chronic pain than from stroke or diabetes, respectively. Not less impressive are the statistics provided by a recent research report,2 which estimates that more than 1.5 billion people worldwide suffer from chronic pain, and that approximately 3–4.5% of the global population are afflicted with neuropathic pain, resulting in concerted efforts by the scientific community to tackle this health problem. The approaches range from the identification of the molecules that might be involved in the persistence of pain and to the emotional experience associated with it. Preceded by a few short general comments, we refer here to recent studies, mainly derived from our laboratories, focusing on a very specific question: namely, whether brain-borne IL-1β could be one of the factors involved in neuropathic chronic pain, an aspect that, at present, can only be explored in animal models.

Neuropathic pain in animal models

Neuropathic pain is a persistent type of pain that usually results from injury or disease of the nervous system. Neuropathic pain was originally classified as central or peripheral depending on whether the primary insult is on the peripheral or the central nervous system. In humans, central neuropathic pain is found, for example, in spinal cord injury and multiple sclerosis, while common causes of peripheral neuropathic pain are infection with herpes zoster, nutritional deficiencies, compression of a peripheral nerve by a tumor, or physical trauma to a nerve trunk. This separation, however, does not seem to be tenable at present because of the pathophysiological mechanisms involved. A discussion of these complex mechanisms is beyond the scope of this article, and the reader is referred to excellent reviews on this topic.3–5

The most common models to study neuropathic pain in animals are based on manipulations on a peripheral nerve, either by a chronic constriction injury (CCI) or a spare nerve injury (SNI). In the CCI model, one sciatic nerve is exposed above the trifurcation and ligated with knots. In the SNI model, one sciatic nerve is exposed at the level of its trifurcation, each of the tibial and common peroneal nerves are completely severed in between, and the sural nerve is left intact. It has been reported that SNI results in irreversible damage of the sciatic nerve while the effects of CCI are at least in part reversible.6,7 Hyperalgesia, which implies an extreme reaction to a moderate stimulus, and allodynia, a withdrawal response to non-noxious tactile or thermal stimulus that normally does not provoke pain, are among the behavioral parameters that are evaluated as indication of pain in these models. In most studies of this type, the response observed at the side contralateral to that in which the nerve was injured or sham-operated animals are used as control.

IL-1β can induce pain

A review of the literature makes it difficult to fix the historical point of, not only when, but also which, was the first cytokine discovered. Cytokines seem to have been rediscovered, with new functions being reported in the last years, depending on the particular field of research. It is likely that at least one of the first cytokines discovered was IL-1.8 In relation to pain, Ferreira and colleagues showed more than 20 years ago that IL-1β can act as a potent hyperalgesic agent.9 In these experiments, IL-1β was injected intraplantarally or intraperitoneally, and the authors proposed that the cytokine acts at peripheral levels. This result has been confirmed by other groups.10 Recent reviews and references on how cytokines can induce pain acting at peripheral levels can be found in 11,12. However, more recently, it has also been shown that, although animals that lack IL-1β signaling show reduced mechanical allodynia, the cytokine is necessary to recover sciatic nerve functions.13

Other cytokines that have been consistently demonstrated to be involved in neuropathic pain are TNF-β and IL-6 (for review see Ref. 3 and 14).

Peripheral nerve injury induces IL-1β expression at local and spinal cord levels

Sciatic nerve transection and CCI result in increased local IL-1 expression in the damaged nerve, the dorsal root ganglia, and the spinal cord (see Refs. 15–17, 19, and for review, see Refs. 14 and 12. One intriguing fact is that some groups have reported that IL-1β is also expressed in the contralateral, nonoperated rat sciatic nerve.20,21 In a model of sciatic nerve microcrush lesions, it has been shown that IL-1 expression and recovery of locomotor function is MyD88-dependent.22 This finding is interesting in this context because this adaptor protein mediates, although not exclusively, the known proinflammatory effects of IL-1.

IL-1β expression at supraspinal levels during chronic pain

There is ample evidence that neuropathic pain behavior in rodents is accompanied by reorganization of peripheral and spinal cord nociceptive processing, giving rise to central sensitization.23 However, cytokine expression in pain states has rarely been studied above the spinal cord. We started our studies on the possible expression of IL- 1β in selected brain regions because of evidence showing that this cytokine is involved in the modulation of nociceptive information,24 and investigation of the hypothesis that supraspinal circuitry plays a role in the transition from acute to chronic pain.25,26 Restricting the discussion to the central nervous system (CNS), the pharmacological studies available indicated that central administration of IL-1β can induce analgesia or hyperalgesia depending on the brain region involved and on the dose injected: lower doses cause hyperalgesia and higher doses are analgesic.24,27 However, at that time, there were no reports on possible changes in endogenous IL-1β expression at supraspinal levels during chronic neuropathic pain.

We first examined IL-1β mRNA expression in the brainstem, thalamus, and prefrontal cortex in the two models of neuropathic pain mentioned above, 10 and 24 days after nerve injury, in male Wistar–Kyoto rats.28 One reason to choose these regions is the anatomy of nociceptive transmission. The thalamus is the main termination site for the spinothalamic pathway, and the brainstem contains structures for ascending nociceptive pathways and important descending modulatory structures. Another reason is that metabolic abnormalities and decreased gray matter density have been reported in the prefrontal cortex and thalamus of patients with chronic back pain.29,30 Neuropathic pain-like behavior was monitored by tracking tactile thresholds. Neither significant changes in threshold sensitivity nor in IL-1β expression in the brain regions mentioned were detected in CCI-injured rats. In contrast, SNI-injured animals showed a robust and substained decrease in tactile thresholds of the injured foot, and increased IL-1β expression was observed in the brainstem and in the prefrontal cortex contralateral to primarily the injury side ten days after injury. Only a modest increase in IL-1β expression was observed in the thalamus/striatum in the side contralateral to the injury on day 24. Interestingly, a positive correlation between threshold sensitivity in the injured paw and IL-1 expression on the ipsilateral side of the prefrontal cortex was detected in SNI-rats, while no correlation was present in sham-operated or untouched control animals. These results were the first indication that neuro-immune activation in neuropathic pain conditions includes supraspinal brain regions, and suggested that IL- 1β modulation of supraspinal circuitry of pain may be involved in neuropathic conditions.28

We then explored whether IL-1β expression was altered also in the hippocampus during chronic neuropathic pain. Several reasons motivated us to include this region. The first was that the hippocampus has been proposed as one of the critical limbic components involved in the transition from acute to chronic pain.25,26 Second, the hippocampus interacts with the prefrontal cortex, a region in which, as mentioned above, we had detected increased IL-1β expression during neuropathic pain, and that therefore may be correlated with a potential expression of this cytokine in the hippocampus. Furthermore, there was evidence of abnormal hippocampal function (for review, see Ref. 31) and impaired neurogenesis32,33 in chronic pain. Another line of evidence, related to long-term potentiation (LTP) and learning, has indicated that the hippocampus may be a potential region in which IL-1β could be altered during neuropathic pain. A recent study found that neuropathic animals exhibit working memory deficits and decreased LTP, although the changes were not related to the pain behavior of the animals.34 On the other hand, we have shown that in vivo and in vitro LTP induction in the hippocampus results in a long lasting increase in IL-1β expression, and that blockade of IL-1 signaing impairs the maintenance of LTP.35 It has also been shown that IL-1 can affect learning of hippocampus-dependent tasks.36–38 Finally, another group showed that the expression of IL-1β is decreased in the hippocampus hours after peripheral nerve injury.39 In our view, however, the extent to which the changes described reflected general stress or effects of pain remained unclear. Furthermore, our main purpose was to explore alterations in IL-1 expression that could occur during the more chronic phase of neuropathic pain, and not early immediate effects that could be evoked soon after nerve injury. In any case, taken together, the evidence summarized indicated the possibility that IL-1β expression in the hippocampus could be affected during chronic neuropathic pain. To address this hypothesis, we chose again the two models of neuropathic pain mentioned above because they display different degrees of pain behavior in response to nerve injury.6,40 We also included two different rat strains (Wistar–Kyoto and Sprague–Dawley) since it is known that there is a large variation in neuropathic pain behavior not only between inbred and outbred strains, but also even between substrains.41,42 Based on the results showing changes in IL-1β gene expression in the prefrontal cortex contralateral to the injury side, we first concentrated in the evaluation of this cytokine in the contralateral side of the hippocampus at different times after nerve injury. We found that, in fact, both injury models resulted in pain-like behaviors that differed in intensity and duration in the two rat strains, and the changes in IL-1β gene expression in the hippocampus agreed with these diiferences.43

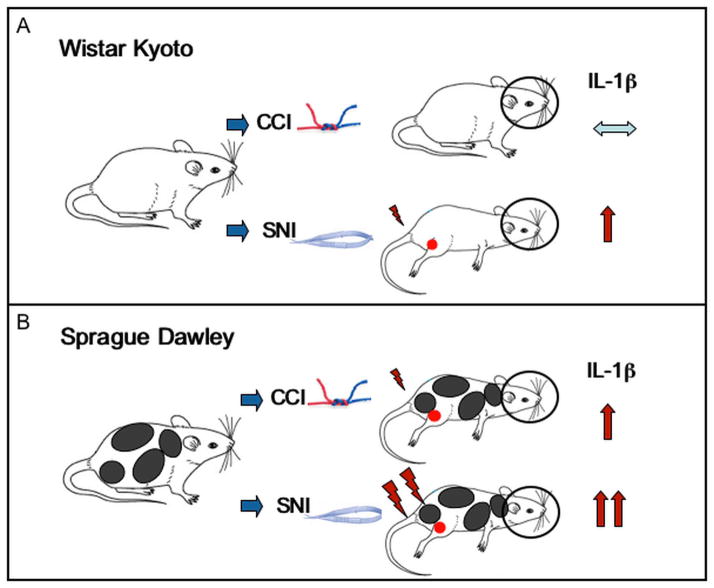

CCI, which did not produce any significant effect on tactile thresholds in Wistar–Kyoto rats, failed to induce significant changes in hippocampal IL-1β expression as compared to the sham-operated controls. However, SNI resulted in elevated mechanical hypersensititvity in this strain, and IL-1β mRNA levels were significantly increased 10 and 24 days after injury in the contralateral hippocampus. In Sprague–Dawley rats, both injury models resulted in significantly decreased tactile thresholds. Interestingly, while the allodynia was maintained for more than two months in the animals that had undergone SNI, the decreased threshold sensititvity following CCI was nearly recoved by this time. In line with these behavioral effects, IL-1β mRNA expression in the contralateral hippocampus was significantly increased two weeks after surgery in both pain models, but remained significantly elevated up to two months only in rats with SNI. These results are schematically summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

IL-1β expression in the contralateral hippocampus depends on the pain model and rat strain. (A) In Wistar–Kyoto rats, while CCI did not produce any significant effect on tactile thresholds and no significant changes in hippocampal IL-1β expression, SNI resulted in elevated mechanical hypersensititvity and significantly increased IL-1β mRNA levels in the contralateral hippocampal side. (B) In Sprague–Dawley rats, both injury models resulted in significantly decreased tactile thresholds. CCI-induced decreased threshold sensititvity recoved gradually, while allodynia was maintained for more than two months in the animals that had undergone SNI. The temporal expression on IL-1β mRNA in the contralateral hippocampus agreed with these behavioral effects.

Also in the hippocampus, the changes were restricted to the contralateral hippocampus, and no significant changes were detected in the side of the hippocampus ipsilateral to the nerve injury. This clear hemispheric lateralization of cytokine expression following SNI or CCI indicate that the changes in cytokine expression are not due a stress response, since the latter is expected to result in bilateral effects. Our results apparently contradict those reported by Al-Amin et al.,44 showing bilateral increases in hippocampal IL-1β levels and even more expression in the ipsilateral than in the contralateral side in the CCI model. However, differences in the experimental design (in the mentioned publication, the animals received daily i.p. injections of a vehicle), animal sex, and the intensity of the pain manifestation could account for this discrepancy.

Supporting a link between the pain-like behavior, as reflected by the tactile threshold, and IL-1β overexpression in the contralateral hippocampus, a linear correlation between both variables was observed in both strains and for both nerve injury models. Allodynia, when present, was only manifested in the hind paw ipsilateral to the peripheral nerve injury.

Another interesting observation that derived from these studies was that the effect of SNI and CCI on the endogenous IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL1ra) and IL-6 expression in the hippocampus was different in Sprague–Dawley as compared to that in Wistar–Kyoto rats. IL-6 was only increased in Wistar–Kyoto rats with SNI ten days after surgery, and no significant changes were detected for this cytokine in Sprague–Dawley rats in any of the two models. No significant changes in IL-1ra were observed in Wistar–Kyoto rats with CCI or SNI, but the IL-1 antagonist was significantly increased in Sprague–Dawley rats in both injury models (for details about these results, see Ref. 43). Interestingly, IL-1β mRNA levels in the hippocampus of sham-operated Sprague–Dawley rats positively correlated with those of IL-1ra and IL-6. The fact that these correlations were not observed in animals with peripheral nerve injury indicates that the interactions between these cytokine are disrupted in the hippocampus of animals with chronic pain.

In summary, this study showed that: (1) the degree and development of neuropathic pain are correlated with specific nerve injury models and rat strains; (2) hippocampal IL-1β expression is correlated with pain behavior; (3) the alterations in cytokine expression are restricted to brain regions contralateral to the injury side; and (4) neuropathic pain seems to disrupt a network of cytokine interactions in the hippocampus. These results are schematically shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

IL-1β expression in the contralateral hippocampus correlates with the intensity of pain-like behavior, but not with IL-6 or IL-1ra. (A) IL-1β overexpression in the hippocampus correlates with pain-like behavior, as reflected by the tactile thresholds, in both strains and for both nerve injury models. (B) The changes in IL-1β expression are restricted to the contralateral side of the hippocampus. (C) While IL-1β expression positively corrrelated with IL-6 and IL-1ra expression in the contralateral hippocampus of sham-operated rats, these correlations are lost in animals in which the left sciatic nerve was injured.

The different intensity and duration of the nerve injuries in the pain-like behavior of Wistar–Kyoto and Sprague–Dawley rats proved to be a good choice for our purposes. At the same time, the results highlight the importance of considering not only the species, but also the strain and model of injury when studying chronic pain. More importantly, however, they point to the difficulty of extrapolating results from animal experiments to humans with chronic neuropathic pain.

What are the functional consequences of increased IL-1β expression in the brain during neuropathic pain?

The findings discussed above indicate a causal relation between neuropathic pain-like behavior and expression of IL-1β in the brain regions studied, implying synaptic reorganization of these regions. However, a positive relation between threshold sensitivity and brain-borne cytokine expression does not allow for concluding whether the animals showed increased allodynia because IL-1β, or, conversely, if increased cytokine expression results in increased pain-like behavior. Studies showing that pain behavior is attenuated in animals in which IL-1 signalling is permanently impeded45,46 cannot answer this question. We are aware of only one publication using neuropathic pain models in which IL-1 was neutralized directly in the brain and where the functional consequence of IL-1 neutralization on mechanical allodynia was tested. In this study, injection of an anti–IL-1 antibody in the Red nucleus significantly attenuated mechanical allodynia, but this was not paralleled by changes in IL-1β immunoreactivity in the hippocampus.47 Studies in which IL-1 was neutralized by peripheral or intrathecal administration of IL-1ra45,48 show that this treatment attenuates the allodynic response to peripheral nerve injury. However, direct proof that brain-borne IL-1 plays a functional role during pain could only be obtained by blocking its effects in defined brain regions in which the cytokine is overexpressed, and at defined times after injury. In addition to the intrinsic experimental difficulties, this would also affect several neuroendocrine, metabolic, and immune parameters (for review, see Ref. 49).

As mentioned, IL-1β is involved in the regulation of synaptic plasticity and memory processes.35–37,50–52 Thus, it is conceivable that changes in IL-1 overexpression in the brain would have functional consequences for the deficits in cognitive functions reported in patients and animals with chronic pain.34,53–55 However, we are not aware of any study at present that has directly approached these possible links. Recently published evidence that acute interference of IL-1 signals in the brain reduces the depressive-like symptoms observed during SNI56 indicates that overexpression of IL-1 in the hippocampus may be relevant for these symptoms.

It is clear that much more needs to be done to clarify the pathophysiological links between brain-borne IL-1, chronic neuropathic pain, and brain functions. Adding to this already complicated scenario, it seems necessary to stress again that we have concentrated here on discussing only IL-1β; however, this cytokine is part of a complex network composed of other cytokines as well, such as IL-6 and TNF-β, which are known to be also involved in neuropathic pain behavior.

Acknowledgments

The studies described in this article were funded by NIH NINDS RO1 NS057704 (AVA), and NINDS RO1 NS064091 (MM).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.http://www.painmed.org/patientcenter/facts_on_pain.aspx.

- 2.Global Industry Analysts, I. R. 2011 Jan 10; http://www.prweb.com/pdfdownload/8052240.pdf.

- 3.Myers RR, Campana WM, Shubayev VI. The role of neuroinflammation in neuropathic pain: mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Drug Discov Today. 2006;11:8–20. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03637-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pace MC, et al. Neurobiology of pain. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:8–12. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmermann M. Pathobiology of neuropathic pain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;429:23–37. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01303-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett GJ, Xie YK. A peripheral mononeuropathy in rat that produces disorders of pain sensation like those seen in man. Pain. 1988;33:87–107. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim KJ, Yoon YW, Chung JM. Comparison of three rodent neuropathic pain models. Exp Brain Res. 1997;113:200–206. doi: 10.1007/BF02450318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinarello CA. A clinical perspective of IL-1beta as the gatekeeper of inflammation. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:1203–1217. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferreira SH, et al. Interleukin-1 beta as a potent hyperalgesic agent antagonized by a tripeptide analogue. Nature. 1988;334:698–700. doi: 10.1038/334698a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zelenka M, Schafers M, Sommer C. Intraneural injection of interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha into rat sciatic nerve at physiological doses induces signs of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2005;116:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sommer C, Kress M. Recent findings on how proinflammatory cytokines cause pain: peripheral mechanisms in inflammatory and neuropathic hyperalgesia. Neurosci Lett. 2004;361:184–187. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ren K, Torres R. Role of interleukin-1beta during pain and inflammation. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nadeau S, et al. Functional recovery after peripheral nerve injury is dependent on the. proinflammatory cytokines IL-1beta and TNF: implications for neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2011;31:12533–12542. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2840-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uceyler N, Sommer C. Cytokine regulation in animal models of neuropathic pain and in human diseases. Neurosci Lett. 2008;437:194–198. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeLeo JA, Colburn RW, Rickman AJ. Cytokine and growth factor immunohistochemical spinal profiles in two animal models of mononeuropathy. Brain Res. 1997;759:50–57. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shamash S, Reichert F, Rotshenker S. The cytokine network of Wallerian degeneration: tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1alpha, and interleukin-1beta. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3052–3060. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03052.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee HL, et al. Temporal expression of cytokines and their receptors mRNAs in a neuropathic pain model. Neuroreport. 2004;15:2807–2811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rotshenker S, Aamar S, Barak V. Interleukin-1 activity in lesioned peripheral nerve. J Neuroimmunol. 1992;39:75–80. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(92)90176-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okamoto K, et al. Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine gene expression in rat sciatic nerve chronic constriction injury model of neuropathic pain. Exp Neurol. 2001;169:386–391. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleinschnitz C, et al. Contralateral cytokine gene induction after peripheral nerve lesions: dependence on the mode of injury and NMDA receptor signaling. Brain Research Mol Brain Res. 2005;136:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruohonen S, et al. Contralateral non-operated nerve to transected rat sciatic nerve shows increased expression of IL-1beta, TGF-beta1, TNF-alpha, and IL-10. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;132:11–17. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00281-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boivin A, et al. Toll-like receptor signaling is critical for Wallerian degeneration and functional recovery after peripheral nerve injury. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12565–12576. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3027-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woolf CJ, Salter MW. Neuronal plasticity: increasing the gain in pain. Science. 2000;288:1765–1769. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bianchi M, Dib B, Panerai AE. Interleukin-1 and nociception in the rat. J Neurosci Res. 1998;53:645–650. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980915)53:6<645::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Apkarian AV. Pain perception in relation to emotional learning. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008;18:464–468. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Apkarian AV, Hashmi JA, Baliki MN. Pain and the brain: specificity and plasticity of the brain in clinical chronic pain. Pain. 2011;152:S49–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hori T, et al. Pain modulatory actions of cytokines and prostaglandin E2 in the brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:269–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Apkarian AV, et al. Expression of IL-1beta in supraspinal brain regions in rats with neuropathic pain. Neurosci Lett. 2006;407:176–181. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Apkarian AV, et al. Chronic back pain is associated with decreased prefrontal and thalamic gray matter density. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10410–10415. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2541-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grachev ID, Fredrickson BE, Apkarian AV. Abnormal brain chemistry in chronic back pain: an in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Pain. 2000;89:7–18. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00340-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu MG, Chen J. Roles of the hippocampal formation in pain information processing. Neurosci Bull. 2009;25:237–266. doi: 10.1007/s12264-009-0905-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duric V, McCarson KE. Persistent pain produces stress-like alterations in hippocampal neurogenesis and gene expression. J Pain. 2006;7:544– 555. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.01.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Terada M, et al. Suppression of enriched environment-induced neurogenesis in a rodent model of neuropathic pain. Neurosci Lett. 2008;440:314–318. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ren WJ, et al. Peripheral Nerve Injury Leads to Working Memory Deficits and Dysfunction of the Hippocampus by Upregulation of TNF-alpha in Rodents. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;36:979–992. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schneider H, et al. A neuromodulatory role of interleukin-1beta in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7778–7783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Avital A, et al. Impaired interleukin-1 signaling is associated with deficits in hippocampal memory processes and neural plasticity. Hippocampus. 2003;13:826–834. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Depino AM, et al. Learning modulation by endogenous hippocampal IL-1: blockade of endogenous IL-1 facilitates memory formation. Hippocampus. 2004;14:526–535. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yirmiya R, Winocur G, Goshen I. Brain interleukin-1 is involved in spatial memory and passive avoidance conditioning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2002;78:379–389. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2002.4072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uceyler N, Tscharke A, Sommer C. Early cytokine gene expression in mouse CNS after peripheral nerve lesion. Neurosci Lett. 2008;436:259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Decosterd I, Woolf CJ. Spared nerve injury: an animal model of persistent peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain. 2000;87:149–158. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00276-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lovell JA, et al. Strain differences in neuropathic hyperalgesia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;65:141–144. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoon YW, et al. Different strains and substrains of rats show different levels of neuropathic pain behaviors. Exp Brain Res. 1999;129:167–171. doi: 10.1007/s002210050886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.del Rey A, et al. Chronic neuropathic pain-like behavior correlates with IL-1β expression and disrupts cytokine interactions in the hippocampus. Pain. 2011;152:2827–2835. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Amin H, et al. Chronic dizocilpine or apomorphine and development of neuropathy in two animal models II: effects on brain cytokines and neurotrophins. Exp Neurol. 2011;228:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gabay E, et al. Chronic blockade of interleukin-1 (IL-1) prevents and attenuates neuropathic pain behavior and spontaneous ectopic neuronal activity following nerve injury. Eur J Pain. 2011;15:242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolf G, et al. Impairment of interleukin-1 (IL-1) signaling reduces basal pain sensitivity in mice: genetic, pharmacological and developmental aspects. Pain. 2003;104:471–480. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Z, et al. Interleukin-1 beta of Red nucleus involved in the development of allodynia in spared nerve injury rats. Exp Brain Res. 2008;188:379–384. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1365-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Milligan ED, et al. Spinal glia and proinflammatory cytokines mediate mirror-image neuropathic pain in rats. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1026–1040. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-01026.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Besedovsky HO, del Rey A. Central and peripheral cytokines mediate immune-brain connectivity. Neurochem Res. 2011;36:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bellinger FP, Madamba S, Siggins GR. Interleukin 1 beta inhibits synaptic strength and long-term potentiation in the rat CA1 hippocampus. Brain Res. 1993;628:227–234. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90959-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Katsuki H, et al. Interleukin-1 beta inhibits long-term potentiation in the CA3 region of mouse hippocampal slices. Eur J Pharmacol. 1990;181:323–326. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90099-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yirmiya R, Goshen I. Immune modulation of learning, memory, neural plasticity and neurogenesis. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:181–213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Apkarian AV, et al. Chronic pain patients are impaired on an emotional decision-making task. Pain. 2004;108:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hu Y, et al. Amitriptyline rather than lornoxicam ameliorates neuropathic pain-induced deficits in abilities of spatial learning and memory. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010;27:162–168. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e328331a3d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ji G, et al. Cognitive impairment in pain through amygdala-driven prefrontal cortical deactivation. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5451–5464. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0225-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Norman GJ, et al. Stress and IL-1beta contribute to the development of depressive-like behavior following peripheral nerve injury. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:404–414. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]