Abstract

Comment on: Khoronenkova SV, et al. Mol Cell 2012; 45:801-13.

Keywords: ATM, DNA damage, p53, phosphorylation, PPM1G, protein stability, signal transduction, USP7/HAUSP

The ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) protein kinase is widely accepted to play a key role in the DNA damage response, in particular in the signaling of radiation-induced DNA double-strand breaks.1,2 In this regard, ATM activates a number of cell cycle checkpoints to delay DNA replication and ensure the correct processing of the damaged DNA.3 This is achieved both directly, through phosphorylation of p53 at Ser15, and indirectly, via phosphorylation of Mdm2, Mdmx and Chk2, which subsequently control the cellular levels of the p53 tumor suppressor. Consequently, this causes activation of either a G1 cell cycle delay, to allow DNA repair processes to be completed before DNA replication, or the initiation of the apoptotic pathway in the case of excessive DNA damage. ATM also plays a key role in the activation of S-phase, as well as G2/M-phase arrest via phosphorylation of BRCA1, SMC1, FANCD2 and many other substrates (for review, see ref. 4) and was proved to be activated and thus regulate some of its targets in response to oxidative stress.5 In total, more than several hundred ATM substrates were identified in global proteome screening in cells subjected to IR, which include a number of transcription factors, proteins that sense and transmit DNA damage signals as well as those that mediate chromatin remodeling, DNA replication, mitosis and other cellular processes6

Despite the extensive research performed in the field of discovering new ATM substrates and their functions, there are still more intriguing discoveries to come. In this context, Khoronenkova et al.7 recently proposed a mechanism as to how the IR-induced DNA damage signal is quantitatively transmitted downstream from ATM in order to coordinate a p53-dependent DNA damage response and thus provided a new insight into our understanding of the regulation of p53 stability in response to acute DNA damage. In this work, the Dianov lab used an elegant biochemical approach to identify the in vivo modulators of the deubiquitylation enzyme USP7, also known as HAUSP, under endogenous as well as acute DNA damage load. This protein is known to deubiquitylate and thus stabilize the E3 ligase Mdm2, which controls the cellular levels of the p53 protein. Additionally, USP7 plays a major role in regulating genome stability and cancer prevention by controlling many other key proteins involved in the cellular DNA damage response, including FOXO4, PTEN and claspin,8 and deletion of USP7 has been shown to result in early embryonic lethality, mainly due to increased p53 levels.9 Despite the importance of this protein in cellular functioning, the mechanism as to how USP7 levels are regulated and the identity of the DNA damage-inducible regulatory pathways for this protein were unknown.

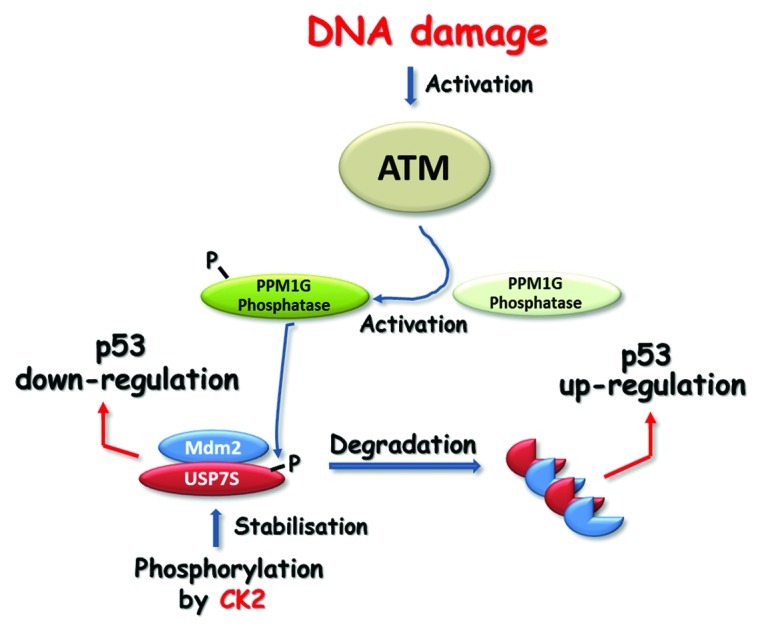

Khoronenkova et al., using fractionation of cellular extracts, USP7 protein and phosphospecific antibodies, purified and further identified by mass spectrometry a protein kinase and phosphatase involved in control of phosphorylation of the serine 18 residue of USP7. Phosphorylation by the protein kinase CK2 was proved to maintain the stability of the USP7 protein by preventing its ubiquitylation and subsequent proteasomal degradation. The majority of cellular USP7 was consequently shown to be phosphorylated, and, thus, the protein was demonstrated to be relatively stable under endogenous conditions. Since USP7 is known as a major regulator of Mdm2 and, consequently, p53 levels, the authors hypothesized that in order to accumulate p53 protein, USP7 needs to be destabilized in response to acute DNA damage stress. This hypothesis proved to be correct, as quite substantial destabilization of USP7 was observed at an early stage of the cellular response to IR-induced DNA damage. The authors demonstrated that USP7 degradation is initiated by the PPM1G protein phosphatase, which is activated by ATM-dependent phosphorylation in response to DNA damage. This leads to Mdm2 downregulation and consequent upregulation of the p53 protein (Fig. 1), suggesting an important role for PPM1G in DNA damage signal transduction. PPM1G-depleted cells, due to their inability to sense even endogenous DNA damage, were unable to accomplish the repair of DNA damage before entering S-phase and were shown to accumulate unrepaired DNA strand breaks. These cells were therefore discovered to behave similar to p53-null cells in that they first enter DNA replication without a cell cycle delay for DNA repair, and only then do they induce a backup mechanism and block replication in a p53-independent, but DNA damage-dependent, mechanism in the second G1 phase.

Figure 1. The majority of cellular USP7S is stabilized by CK2-dependent phosphorylation. USP7S deubiquitylates and stabilizes Mdm2, which leads to p53 ubiquitylation and downregulation. In response to DNA damage, activated ATM phosphorylates and activates PPM1G, which, in turn, dephosphorylates USP7S, thus promoting its degradation. Inactivation of USP7S results in Mdm2 self-ubiquitylation and degradation that leads to p53 upregulation.

Nevertheless, it should be stressed that as long as USP7 controls a variety of substrates, the performed study is not limited to the Mdm2-p53 axis only. In fact, this study opens up a multitude of tools and ideas that can be used to further investigate USP7-dependent cellular responses to DNA damage.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/20800

References

- 1.Jackson SP. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:687–96. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.5.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiloh Y. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11:71–7. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(00)00159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abraham RT. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2177–96. doi: 10.1101/gad.914401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavin MF, et al. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:931–42. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.8.4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ditch S, et al. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuoka S, et al. Science. 2007;316:1160–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1140321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khoronenkova SV, et al. Mol Cell. 2012;45:801–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicholson B, et al. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2011;60:61–8. doi: 10.1007/s12013-011-9185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cummins JM, et al. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:689–92. doi: 10.4161/cc.3.6.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]