Abstract

Membrane proteins (MPs) are often desirable targets for antibody engineering. However, the majority of antibody engineering platforms depend implicitly on aqueous solubility of the target antigen which is, at best, problematic for MPs. Recombinant, soluble forms of MPs have been successfully employed as antigen sources for antibody engineering, but heterologous expression and purification of soluble MP fragments remains a challenging and time-consuming process. Here we present a more direct approach to aid in the engineering of antibodies to MPs. By combining yeast surface display technology directly with whole cells or detergent-solubilized whole-cell lysates, antibody libraries can be screened against MP antigens in their near-native conformations. We also describe how the platform can be adapted for using MP-containing cell lysates for antibody characterization and antigen identification. This collection of compatible methods serves as a basis for antibody engineering against MPs and it is predicted that these methods will mature in parallel with developments in membrane protein biochemistry and solubilization technology.

Keywords: antibody, scFv, yeast surface display, biopanning, cell lysate, membrane protein

1. INTRODUCTION

Membrane resident receptors comprise the majority of all proteins targeted by FDA-approved drugs and experimental therapeutics entering clinical trials [1]. A current trend in drug development is a push toward biopharmaceuticals, notably fully human monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) [2–4], that can be used to target such MPs. Generation of lead MAbs is most often based on platform technologies, including the immunization of transgenic animals or the screening of large, recombinant antibody libraries [5]. These platforms oftentimes rely on one critical element for generating and characterizing MAbs: a soluble form of the protein target [6, 7]. The “drug” effect of an MAb consists of binding to an epitope on its protein target. This binding can lead to a desired compromise in the target’s activity (often influencing downstream cellular and/or systemic events) [8, 9], or can initiate localized delivery of a drug payload [10, 11]. It is therefore paramount that antibodies bind target protein epitopes in their native conformations [12, 13]. These requirements for soluble and native-like MPs are particularly limiting given the nature of membrane proteins. Full-length membrane proteins are poorly soluble without the combination hydrophobic-hydrophilic interactions presented by lipids, and once introduced to a purely aqueous environment, membrane proteins are prone to misfolding, aggregation, and denaturation [14]. Soluble, recombinant peptides (usually comprised of extracellular domains or fragments) produced in microbial or mammalian hosts may lack the proper post-translational modifications, are time-consuming to produce and purify, and may ultimately present a different target than what exists in vivo [15]. Whole cells, and detergent-soluble cell lysates are a direct, powerful solution to this problem, provided that they can be integrated into popular antibody discovery platforms. Indeed, as antibody engineering technology has matured, many examples have emerged with whole cells playing the role of antigen.

XenoMouse technology and phage display, two widely used platforms for antibody discovery, incorporate whole cells as a means of generating antibodies against membrane proteins. The research and development leading to panitumimab (Vectibix) [16, 17] provides an instructional review of the XenoMouse platform where the engineered animals were immunized by direct injection of antigen-expressing cells. Additional flexibility was enabled through the development of HEK293 expression vectors, capable of accepting a variety of membrane proteins [18]. Phage display, being an in vitro platform, is highly adaptable to the use of whole cells. Studies have succeeded in identifying reactive peptides and antibodies to many cells and tissues including: brain and kidney [19], lung [20], heart [21], and breast tissue [22]. Recent years have also seen the first in vivo phage selection performed in humans [23]. These results briefly highlight the use of whole cells in the prevailing antibody discovery platforms. The technology used for antibody discovery and production, however, has progressed dramatically, leading to alternative cell-surface display technologies [24]. One of these, yeast surface display (YSD), has gained in popularity among academic researchers and has recently been commercialized [25]. Here we describe powerful YSD methods using whole cells (yeast biopanning) or detergent-solubilized cell lysates as sources of MP for antibody engineering.

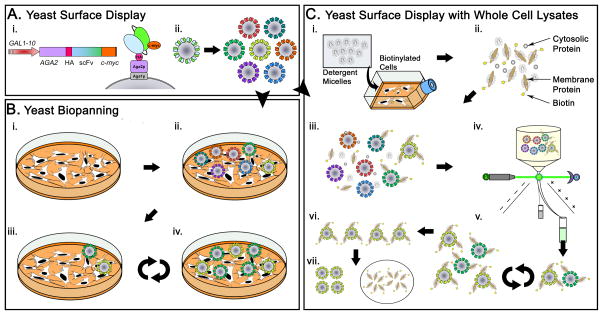

Yeast-display is among the many cell-surface display systems for protein engineering and as will be described in this review, possesses advantages for antibody engineering against membrane proteins [24, 26]. Much like phage display, yeast are engineered to express peptides or antibody fragments on their surface while harboring the genetic information via a plasmid inside the cell (Figure 1A). Being eukaryotes, yeast also have an endoplasmic reticulum equipped with specific enzymes and chaperones that lead to high fidelity folding and expression of mammalian antibody fragments. Enhanced protein folding, when combined with the ability to generate very large (~1010 clones) libraries [27] (Figure 1A-ii) leads to a powerful platform for the identification of novel antibodies [28]. Importantly, yeast display also allows the use of fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (Figure 1C-iv) which affords an impressive combination of quantitative screening and throughput. Modern FACS instruments support rates in excess of 25,000 events per second, allowing even large libraries to be screened quickly and precisely. In the typical embodiment however, YSD requires the use of a soluble antigen (Figure 1C-ii). Two methods have recently been developed to overcome this limitation. First, our lab demonstrated a yeast “biopanning” method where yeast displayed single chain variable fragments (scFv) were selected by successive rounds of incubation on mammalian cell monolayers [29] (Figure 1A, B). Yeast biopanning was later used to isolate a number of unique scFv that bind plasma membrane (PM) proteins of a rat brain endothelial cell line (RBE4), and in some instances, internalized into the RBE4 cells [30]. A second YSD-based method using whole cell contacting approaches incorporated lymphoid-derived cells to screen a library of T-cell receptors against native peptide-MHC ligands [31]. Enrichment of high affinity pMHC binders was aided by separation of yeast-lymphoid cell complexes by density gradient centrifugation. Although incorporation of whole cells overcame the need for a soluble antigen, neither approach took advantage of FACS for high-throughput, quantitative screening as mentioned earlier. Our laboratory overcame this limitation through the use of detergent solubilized whole cell lysates and demonstrated YSD-based screening using the cell lysates as a soluble antigen source [32] (Figure 1A,C). This method allows the high-throughput screening of YSD libraries against MP antigens, while avoiding the problem of MP aggregation and eliminating the need for heterologous production of truncated MPs. We have also demonstrated the use of lysate-based YSD to identify and characterize targeted membrane proteins [33], often one of the most challenging aspects of validating new antibody-antigen combinations. Below, we detail these methods for YSD-based selection and characterization of antibodies against antigens located in the cell membrane, and highlight the various advantages and challenges of such approaches.

Figure 1.

The two components of any yeast surface display screen are yeast-displayed antibody (A-scFv) and an antigen (B-cells or C-cell lysates). The yeast surface display vector directs galactose inducible display of the antibody construct as well as HA and c-myc expression level tags, with high valency on the yeast surface (A-i). Recombinant libraries (nonimmune, immune, mutagenic or a parental clone) are cultured and surface expression is induced (A-ii). In yeast biopanning, monolayers of whole cells act as the antigen (B-i). Induced yeast are incubated on the monolayers (B-ii) and non-specifically bound yeast are removed by washing (B-iii). A library may be enriched for binding yeast through repeated application of this process (B-iv). Cell lysates act as a soluble source of antigen, allowing yeast antibody libraries to be sorted by flow cytometry. Cells are lysed and membrane proteins are solubilized by the addition of a detergent based lysis buffer (C-i). The membrane proteins may be specifically biotinylated prior to lysis as an aid in identifying MP-binding yeast clones. Detergent-solubilized MPs in the form of cell lysate (C-ii) are mixed with scFv-displaying yeast (C-iii), and the resulting mixture is sorted using FACS (C-iv). Repeating this procedure leads to the enrichment of yeast clones that bind a desired antigen (C-v). Membrane proteins may be eluted from the yeast surface in a process termed yeast-display immunoprecipitation (YDIP,C-vi). Separation of the eluted proteins by SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting or mass spectrometry comprises a direct method of antigen characterization (C-vii).

2. OVERVIEW: YEAST SURFACE DISPLAY USING CELLS AND CELL LYSATES

Methods for screening YSD libraries against whole cells or cell lysates simply merge this new means of antigen presentation with many classical YSD techniques. Since its inception [26], yeast-surface display has proven a robust platform for engineering antibodies [34]. The yeast component of YSD are yeast cells displaying antibody fragments (typically single chain variable fragments, scFv) as surface fusions to the Aga1p-Aga2p mating protein complex (Figure 1A-ii). Heterologous display is accomplished using centromere-based, low copy number plasmids under auxotrophic selection [35]. The relevant DNA expression cassette is depicted in Figure 1A-i, and the display construct is under control of the GAL1-10 inducible promoter. Thus, introduction of galactose in the culture medium leads to the display of 104–105 scFv on the yeast surface. As shown in Figure 1A-ii the antibody-bearing yeast may either be clonal or comprise a library of unique clones, depending on the nature of the experimental goals. Libraries are often generated by PCR-based random mutagenesis of a parental clone [36] or by PCR cloning from an in vivo source [37, 38]. Once surface display of the scFv has been achieved, the yeast are ready for screening against cells or cell lysates.

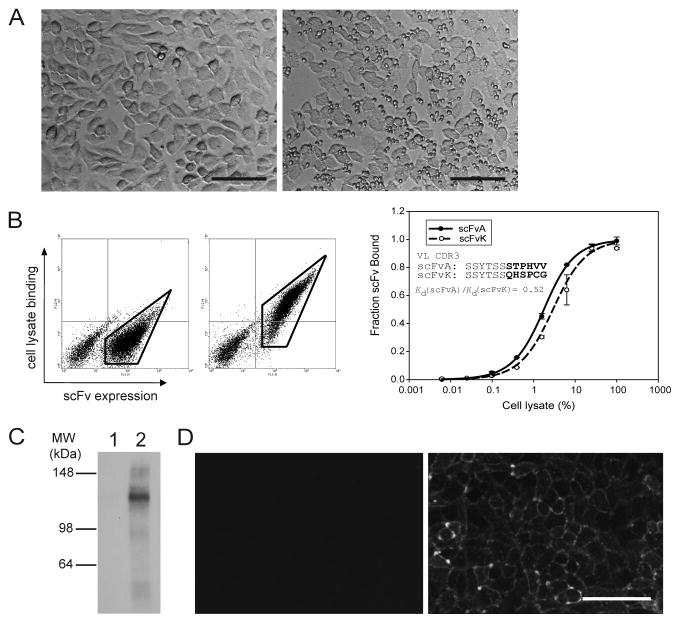

Use of whole cells as an antigen source or “biopanning” is depicted in Figure 1B. The antibody-bearing yeast pool is incubated (Figure 1B-ii) on mammalian cell monolayers (Figure 1B-i). Repeated and controlled, washing of the monolayers removes any yeast which are not specifically bound as a result of the surface-displayed scFv (Figure 1B-iii, Figure 2A). Recovery of the bound yeast is followed by multiple cycles of enriched library regrowth, incubation and washing to isolate specific clones that bind to the cells (Figure 1B-iv).

Figure 2.

Compatibility of yeast biopanning and cell lysate-based methods in screening and characterizing antibodies. (A) Phase contrast image of rat brain endothelial cells after biopanning with yeast expressing non-specific (left, irrelevant scFv) or specific (right, clone scFvA) scFvs. Note the accumulation of binding yeast on top of the cell monolayer in the right panel. Scale bars indicate 50 μm. (B) scFv-target protein interaction can be assessed by FACS using cell lysate. The same scFvA-displaying yeast cells shown in (A) are incubated with biotinylated cell lysate of the target cells. Specific lysate binding is detected for scFvA-displaying yeast (middle panel) but not for control scFv-expressing yeast (left panel). Enclosed regions in left and middle panels are examples of gated c-myc+ populations used to calculate relative binding affinities as described in Section 4.6(f). Right panel: Relative affinities of scFvA and scFvK, which has an identical sequence as scFvA except for 6 amino acids in light-chain CDR3 (inset), by titrating the target cell lysate (shown in terms of percent of a cell lysate containing approximately 2 mg of total protein). Error bars represent standard deviations from two independent measurements. Adapted from ref. [33] (C) Yeast cells expressing scFvs isolated from biopanning can be used to immunoprecipitate and visualize the target antigen by Western blotting. Biotinylated antigen immunoprecipitated from cell lysate with non-specific (lane 1) or specific (lane 2) scFvA-expressing yeast is probed with an anti-biotin antibody to show the molecular weight and the purity of the immunoprecipitated antigen. (D) scFvs can be solubly expressed by yeast to confirm target cell binding. Both the non-specific scFv control (left) and specific scFvA (right) were expressed as soluble protein, purified and used in immunocytochemistry. Scale bar indicates 50 μm.

Cell lysates also enable robust, high-throughput screening of yeast libraries while offering a key tool for antigen characterization (Figure 1C). Importantly, cell lysates-based methods are often compatible with biopanning, in that clones isolated from biopanning can be characterized using cell lysates (Figure 2). The cell lysate (Figure 1C-ii) is created by solubilizing mammalian cells with a detergent-containing buffer (Figure 1C-i). When using cell lysates as an antigen source, a means for detecting antigen binding is required. Biotinylation of live cells (Figure 1C-i) is one approach that can be used to label proteins such that they can be detected when bound by yeast surface-displayed scFv. As discussed later in section 4.2, biotinylation of cellular proteins can also be tuned to meet screening objectives. Induced yeast are then incubated with the cell lysate (Figure 1C-iii) and screened by FACS (Figure 1C-iv). Again, antigen binding clones are recovered and the process repeated for multiple cycles to enrich the population for a desired characteristic (Figure 1C-v). An added benefit of using YSD in combination with cell lysates is the opportunity for antigen identification and characterization. Membrane proteins bound to the yeast surface can be eluted using a low-pH buffer, or ionic detergent (Figure 1C-vi); the eluted membrane proteins are suitable for electrophoresis, Western blotting, and mass spectrometry. This technique, termed yeast display immunoprecipitation (YDIP) may be used with any yeast clone, whether derived from biopanning (Figure 1B, Figure 2B) or flow cytometric screening (Figure 1C, Figure 2C). Thus, cell lysates serve to unify YSD screening approaches for MPs.

A detailed protocol outlining the engineering of human antibodies was published [39], and it’s flexibility is well documented [40]. Rather than reviewing the yeast-surface display literature, we will instead focus on specific areas of the YSD system critical for working with cells and cell lysates as antigen sources. Some general keys to the methodology include monitored yeast growth and induction, appropriate YSD controls, and the physical effects of detergent on yeast cells.

2.1. Yeast growth and induction

Reproducible levels of surface display are critical for library screening and are especially key for comparing the relative properties of multiple antibodies. This task is most easily accomplished by adding an additional growth period prior to induction, leading to well-matched growth and induction phases across all cultures or libraries to be compared. Yeast are grown in dextrose-based SD-CAA media and subsequently, scFv expression is induced in galactose-containing SG-CAA media (See section 3.1 for reagent recipes). Overnight yeast cultures (3 mL in SD-CAA) can be started from plated colonies, frozen stocks, or liquid cultures. The following day (12–18 hours later), the culture density is determined by measuring optical density (OD) at 600 nm. Using these starter cultures, new 3 mL SDCAA cultures are then initiated at 0.3 OD600 (~3×106 yeast/mL), and grown for approximately 4 hours, or until the culture reaches 1.0 +/− 0.2 OD600 (~1×107 yeast/mL). These 1.0 OD600 cultures are then induced for scFv display by culturing the yeast in SG-CAA media. Induction temperatures may range from 20–37°C with 20°C being the most commonly used as it tends to maximize the amount and quality of heterologous expression, particularly scFv [41]. In our hands, optimal induction and display of most scFv takes 16–20 hours at 20°C. As a rule of thumb, the yeast should approximately double in OD600 over the induction period and display 104 – 105 scFvs per cell. However, it should be noted that surface display level is also a function of protein-specific factors such as thermal stability and can vary significantly among identical constructs with small differences in their sequences [42]. If desired, the expression level of scFvs can be readily quantified using antibodies against epitope tags (Figure 1A-i) and the Quantum Simply Cellular ™ kit from Bang’s Labs (Fishers, IN).

2.2. Appropriate YSD controls

When screening a yeast-surface display library, in addition to having an irrelevant scFv to serve as a negative control, it is highly desirable to have a positive control strain that binds an accessible protein epitope on the target cell surface. For example, in the case of biopanning (section 3), we have shown that yeast cells displaying anti-fluorescein scFv 4-4-20 can be efficiently enriched against chemically fluoresceinated target cells [29]. Since the fluoresceination reaction occurs at lysine residues that are exposed to the solution, any target cell of interest can be tested using the anti-fluorescein displaying yeast as a positive control. An appropriate positive control allows for critical experimental feedback on, among many parameters: wash stringency, detergent perturbations to the antibody-antigen interaction, gating/compensation during FACS, and signal-to-noise ratio of fluorescence data [29, 30, 32]. One cautionary note on positive controls in yeast surface display: frequently the library being screened can become “contaminated” by the positive control yeast, because of sample carryover on the flow cytometer. Once this occurs, a typical library will very quickly lose diversity, becoming enriched in control yeast. Thus, it’s highly recommended to subclone any control constructs into a yeast strain or plasmid bearing a different auxotrophic marker [35]. If contamination or carryover were to occur, that standard passaging of the library between screening rounds would be sufficient to clear the library as the necessary nutritional supplements for control yeast are not present.

2.3. Effects of detergents on yeast cells

Finally, it is important to note some observations resulting from the use of detergents in YSD screening. The methods involving detergent solubilized cell-lysates necessitate the use of detergents in the binding and wash buffers, to both solubilize the target antigen(s) and also to overcome non-specific binding. It is known that non-ionic detergents are capable of permeabilizing yeast cells at concentrations <0.1% (v/v) [43, 44], with various effects on cell growth. Importantly, yeast are not lysed, the surface expression of scFv is preserved, and the binding interaction is well maintained in the presence of detergent. Previously, we measured the effect of detergent on antibody-antigen binding, and found that the measured affinity of scFv D1.3 for hen-egg lysozyme varied as little as three-fold over a wide range of detergents [32]. One additional technical manifestation of detergent-based buffers in YSD screening is an observable loss of yeast cells during washing steps, particularly when using smaller numbers of yeast during clonal scFv characterization (Section 4.6(b)). When switching from a detergent containing buffer to buffer alone, the yeast do not pellet well during centrifugation. The risk of aspirating the yeast pellet increases, and even with the utmost care, the amount of yeast after each wash observably shrinks. This effect can be simply countered by starting with 2–4 times more yeast in the characterization process (Section 4.6(b)) keeping in mind that the volume of antigen (at a fixed concentration) must be increased proportionally. As a rule of thumb, it is necessary to collect at least 10,000 events (yeast) for thorough analysis of binding events. Careful technique combined with proper induction of yeast display and the right positive control will yield reliable results and enable the selection of antibodies against membrane proteins.

3. YEAST BIOPANNING

Yeast biopanning is analogous to phage biopanning methods in that antibodies that bind to extracellular epitopes of adherent target cells can be isolated from YSD antibody libraries (Figure 1B). Therefore, the wide variety of target cell types that have been screened using phage display methods could also be used as antigen sources in yeast biopanning experiments. Recently, yeast biopanning has been successfully employed by several laboratories to screen or identify membrane protein binders including scFvs [30], integrins [45], and adhesion molecules derived from pathogens [46, 47]. Although similar in format to phage biopanning, yeast biopanning provides several advantages over phage display based methods. The harsh (potentially denaturing) wash steps commonly used in phage methods [48] are not necessary due to the low non-specific binding of yeast cells to mammalian cells [30]. Second, since a typical yeast cell displays 104 – 105 antibody copies, avidity effects allow the recognition of rare antigens and increased possibility of recovering lower affinity lead molecules characteristic of non-immune antibody libraries [30, 49]. Moreover, the eukaryotic processing machinery of yeast has been shown to allow larger diversity of a given library to be functionally expressed in a direct comparison with the phage display version [28]. Taken together, these features should lead to efficient discovery of novel antibody-target combinations. On the other hand, phage biopanning has been used to isolate antibodies in vivo by perfusion with phage particles and to screen antibodies that lead to endocytosis by collecting intracellular phage, which would be difficult using the yeast biopanning approach. All of these factors should be considered before selecting a display platform and designing the experiment. The reagents and procedures that follow have been extended based on our previous publications [29, 30].

3.1. Materials

EBY100 yeast display strain (Invitrogen C839-00)

Non-immune human scFv yeast library (available from Pacific Northwest National Laboratories), or any other antibody library of interest.

6-well and 96-well TC-treated polystyrene plates (BD Falcon)

Poly-L-Lysine (Sigma-Aldrich P4707)

Collagen, type I, from rat tail (Sigma-Aldrich C7661)

Zymoprep II yeast miniprep kit (Zymo Research)

10mM PBS pH 7.4 (137mM NaCl, 2.7mM KCl). For PBSCM, supplement PBS with 0.9mM CaCl2 and 0.49mM MgCl2.

Wash buffer (PBSCMA) – Supplement PBSCM with 1g/L bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, purified, essentially protease free). Store at 4°C.

SD-CAA - 20.0 g/L dextrose, 6.7 g/L yeast nitrogen base, 5.0 g/L casamino acids, 10.19 g/L Na2HPO4•7H2O, 8.56 g/L NaH2PO4•H2O. Add kanamycin (50 μg/mL) when indicated below.

SG-CAA - SD-CAA replacing dextrose with 20 g/L galactose.

SD-CAA plates - autoclave 10.19 g/L Na2HPO4•7H2O, 8.56 g/L NaH2PO4•H2O, 15 g agar in 900 mL deionized water and cool to about 50 °C. Add 20.0 g/L dextrose, 6.7 g/L yeast nitrogen base, 5.0 g/L casamino acids in 100 mL deionized water by filtration, mix and pour.

Restriction enzyme BstNI (New England Biolabs)

3.2. Cell lines and cell culture

The target cells should be adherent and grown in 6-well plates, which provide optimal washing conditions. The plate surfaces are normally coated with matrices such as collagen or poly-L-lysine to improve cell health and adhesion. The initial seeding density of target cells can vary, but should be aimed to produce a 70–80% confluent monolayer on the day of screening. For example, cell lines such as the RBE4 rat brain endothelial cells are seeded to 25% confluence two days prior to screening. The upper limit of yeast cells that can be screened is 5×107 per cm2 of cultured target cells [29]. It is also important to oversample the yeast display library 10-fold to ensure the isolation of rare antibody clones. Thus, for the first round of screening, at least 100 cm2 of target cells (approximately 10 wells in 6-well plates) are required to oversample a yeast display library with a diversity of 5×108.

3.3. Yeast culture

Inoculate yeast into SD-CAA medium and grow overnight at 30°C, 260rpm in a rotary incubator. For clonal yeast, a single colony from a plate is appropriate for 3 mL of media. For combinatorial libraries, use liquid yeast culture containing 10 to 100 times the library size, inoculated at a concentration of ≤1×107 yeast/mL (1×106 is preferable if equipment allows). The concentration of yeast cells in a liquid culture is determined by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) (diluted appropriately to stay within the instrument’s linear range), with a reading of 1 OD600 being approximately 1×107 yeast per mL.

After overnight growth (12–18 hours), the culture should have expanded to 5–10 OD600. Passage the yeast by diluting into fresh SD-CAA medium at 0.3 OD600.

Grow at 30°C, 260rpm until the culture reaches 1.0 OD600.

-

Pellet the yeast by centrifuging the SD-CAA culture at 2,500g for 5min. Pour off or aspirate the spent SD-CAA media. Initiate induction by resuspending the yeast at in an identical volume of SG-CAA media. Transfer cultures to a growth chamber at 20°C, 260rpm, and induce for 16–20hrs. Yeast are now ready for any of the selection or characterization processes described below.

NOTE – See section 2.1 for rationale underlying these culture parameters. Additional details regarding culture, induction, and maintenance of yeast display antibody libraries can be found in [39].

3.4. Binding detection

Similar to panning of phage on cell monolayers, yeast biopanning is a unified binding and enrichment process as the yeast-displayed antibodies are physically bound to the antigen of interest. Verification or quantification of binding to cells is conducted via light microscopy and should be readily distinguishable, since non-specific binding of yeast to mammalian cells is nearly absent (Figure 2A). For quantitative comparison between samples, yeast cells bound to target cells can be scraped off and plated on selective medium such as SD-CAA for colony counting.

3.5. Yeast biopanning procedure

Yeast cells expressing the scFv library are collected at 10-fold excess of the library size (5×109 yeast if the library size is 5×108). The density of yeast cells is determined by measuring absorbance at 600 nm (OD600 of 1.0 corresponds to roughly 1×107 yeast cells per mL).

Yeast cells are pelleted by centrifugation at 2,500g for 5 min and washed twice in PBSCMA by resuspending the pellet in fresh buffer after each spin.

Wash the target cells three times with PBSCMA.

-

Add yeast cells in PBSCMA dropwise to the target cells (5×108 or less yeast cells per well of a 6-well plate) to ensure even distribution. The plates are incubated without shaking at 4°C for 2 hours to allow yeast-target cell binding.

NOTE – When biopanning against a less homogeneous or less dense culture such as primary cultures, the yeast-target cell contact can be facilitated by rotating the plate gently and increasing the incubation time. If cells of interest detach at 4°C, room temperature or even 37°C incubation can be used.

After incubation, non-binding yeast cells are removed by aspirating the supernatant.

-

1 mL of PBSCMA is added dropwise, to each well of target cells. The plate is then gently rocked twenty five times and rotated five times.

NOTE – The number of times performing plate rocking and rotation should be adhered to precisely as they govern the stringency of the washing step and the enrichment efficiency of the screen. One can optimize these parameters in their own hands using the anti-fluorescein (4-4-20) displaying yeast and fluoresceinated mammalian cells as a positive control and the anti-lysozyme (D1.3) displaying yeast as a negative control as described in ref. [29].

Remove the wash buffer by aspiration.

Repeat steps (e) and (f) for a total of two washes.

-

To complete the washing, add 1 mL wash buffer, rotate the plate ten times, and finally, aspirate the buffer.

NOTE – When rotating the plate, it is more efficient to tilt the plate while rotating rather than keeping it horizontal. The shear force created by the liquid movement removes unbound yeast cells.

After the washing steps, 1 mL of PBSCMA is added to each well and yeast cells bound to target cells are collected by scraping off the plate using a cell scraper.

-

Pool cells from all the wells together, centrifuge cells at 2,500g for 10 min, resuspend in 5 mL SD-CAA supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/mL) and grow at 30°C overnight. When the yeast culture reaches OD600 of 1.0, the yeast cells are diluted once more in 5 mL SD-CAA and cultured until OD600 reaches 1.0 to completely eliminate mammalian cell debris.

NOTE – Before the pooled mixture is cultured in SD-CAA, a small fraction can be plated at multiple dilutions (1:10, 1:100, etc.) on SD-CAA plate to determine the total number of recovered yeast cells. This number is the estimated maximum diversity of the recovered pool. For the first round of screening, the plating step should be omitted to prevent the loss of rare clones. When passaging the recovered yeast culture, make sure to collect at least 10-fold more than the maximum diversity of the pool, to prevent loss of clones.

The above procedure (a-k) is repeated to further enrich the binding yeast population. In each round, prepare sufficient target cells to screen a 10-fold excess of yeast collected in the previous round. Also, the panning density is lowered to 5×106 yeast/cm2 after the first round. For example, if the number of yeast cells isolated in the previous round is 1×107, prepare (10*1×107)/5×106 = 20 cm2 of target cells.

Once the recovery of the binding yeast levels off from round to round (3–7 rounds in our experience), binding clones are isolated. Individual binding clones can be confirmed by performing the high throughput characterization detailed in Section 3.6 below. For confirmed binding clones, the scFv-encoding plasmid can be recovered using the Zymoprep II (Zymo Research) yeast miniprep kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

To confirm the binding attributes are based on scFv function and not spurious yeast mutations, pick several scFv-encoding plasmids, transform into yeast surface display parent strain EBY100 and induce expression. Assess the binding to the target cell using the above biopanning procedure and light microscopy (Figure 2A).

After confirming the binding, the plasmids are sequenced. For the non-immune human scFv display library, we have successful used so-called “Gal1-10” (5′-CAACAAAAAATTGTTAATATACCT-3′) and “alpha terminator” primers (5′-GTTACATCTACACTGTTGTTAT-3′) for standard dideoxy sequencing.

3.6. High throughput characterization of selected clones

To identify binding clones rapidly, yeast clones from an enriched binding pool are singly inoculated into 96-well plates. To test for scFv-mediated binding, one colony is inoculated into two wells, one containing 200 μL SG-CAA (induced) and 200 μL SD-CAA (uninduced) in another. The plate is incubated without shaking at 30°C for 24 hours to allow yeast growth and induction of scFv expression.

In another 96-well plate seed the target cells so that they will reach confluence in 24 hours.

Since yeast multiply faster in SD-CAA compared to the SG-CAA induction medium, mix yeast cells grown in 96-well plates by pipetting to resuspend yeast, then remove 160 μL (yeast plus media) from the uninduced (SD-CAA) columns to balance the number of yeast cells to that of the induced (SG-CAA) columns. Centrifuge the plate at 2,500 g for 5 min to pellet yeast, gently remove media. Add 150 μL wash buffer and resuspend yeast cells. The target cells grown in 96-well plate are also washed with wash buffer.

Transfer yeast cells from the 96-well plate to corresponding wells in the target cell plate and incubate 2 hours at 4°C.

Remove supernatant from each well, add 150 μL wash buffer to one side of well and remove from the other side to the well. This technique creates enough shear force to wash away non-specifically bound yeast cells.

Repeat (e) two more times, for a total of three washes.

-

Assess yeast cell binding under light microscopy (see Figure 2A for typical binding pattern). For specific binders, only the induced well should show binding.

NOTE – To rapidly assess the diversity of isolated binding antibody DNA sequences, BstNI digestion is used. Antibody encoding genes can be directly amplified from yeast colonies grown on agar plates using PCR. Pipette 1 – 2 μL of yeast cells from colonies freshly grown on an agar plate and transfer into 30 μL 0.2% (w/w) SDS in deionized water, vortex, freeze at −80°C for 2 minutes and heat at 95°C for 2 minutes. Repeat the freeze/thaw once more to ensure complete yeast lysis. Use 1 μL of the lysed yeast cells for whole-cell PCR. The PCR reaction mix should contain 0.4% (w/v) Triton X-100 to prevent enzyme denaturation by SDS. For the non-immune human scFv library, primers PNL6 Forward (5′-GTACGAGCTAAAAGTACAGTG-3′) and PNL6 Reverse (5′-TAGATACCCATACGACGTTC-3′) can be used to amplify the scFv gene. 20 μL of the PCR product is digested using BstNI at 60°C for 14 hours, then separated on a 3% agarose gel to assess the digestion pattern. The remaining PCR products can be used for sequencing clones with unique digestion patterns.

4. YEAST SURFACE DISPLAY WITH WHOLE-CELL LYSATES

The use of detergent-solubilized cell lysates as an antigen source allows one to leverage the full spectrum of YSD-based screening techniques against MP targets and provides an important tie to the yeast biopanning methods just discussed. Importantly, detergent lysis of whole cells leads to the solubilization of MPs in full-length, near-native, and often active forms [50–52]. Furthermore, cell lysates are used directly, with very little manipulation, eliminating the need for heterologous MP expression or purification. Lysates are sufficiently concentrated to avoid antigen depletion effects, such as what is encountered in library on library screening [53]. Thus the abilities of classical YSD (e.g. quantitative screening, affinity maturation, and stability engineering [39]) are immediately realized for the new class of MP antigens. In contrast to panning approaches, YSD with a soluble antigen allows one to measure relative antibody affinity with the scFv still tethered to the yeast surface. This greatly speeds the time to isolation of desirable clones from a given library. Moreover, if the library being screened is non-immune, YSD combined with cell lysates possesses an additional advantage: antigen identification. As described above (and shown in figure 1C), YDIP involves the capture and subsequent elution of a soluble or MP antigen using a clonal pool of antibody-displaying yeast. Once isolated via YDIP, the antigen may be characterized and identified via SDS-PAGE and mass-spectrometry. In a recently published study detailing the cell lysate-based YSD methods, our lab successfully isolated scFvs against membrane proteins from the RBE4 rat brain endothelial cell line [32]. We further specifically identified an anti-transferrin receptor (TfR) antibody from the MP-specific antibody pool with a secondary screen uniquely enabled by the YSD approach. In addition, scFvs were secreted in soluble form, purified, and binding to RBE4 cell monolayers was preserved. The following protocols detail cell lysate creation, troubleshooting, YSD screening for scFvs against membrane proteins, and a recap of antigen characterization by YDIP [33].

4.1. Materials

EZ-Link™ Sulfo-NHS-LC Biotin (Thermo-Fisher - Pierce)

10mM PBS, PBSCM from section 3.1 above. For PBSCMG, supplement PBSCM with 100mM Glycine·HCl. For PBSA, supplement PBS with 1 g/L bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Detergent wash buffer (PBSD) – PBS supplemented with the same concentration and type of detergent selected for creation of cell lysates (section 4.3)

Poly-L-Lysine (Sigma-Aldrich P4707)

Collagen, type I, from rat tail (Sigma-Aldrich C7661)

Sterile Cell Scraper (Becton-Dickinson #353086)

T25 and T75, TC-treated polystyrene cell culture flasks (Becton-Dickinson #353014, #353135)

Triton-X100 (Sigma-Aldrich)

n-Octyl-β-D-Glucopyranoside (Affymetrix – Anatrace)

CHAPS (Fisher Scientific)

EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich)

Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich P8340), or complete, mini, EDTA-free tablets (Roche #1836170)

Biotin (Fisher Scientific)

Mouse anti-c-myc antibody (9E10, Covance) – 1:100 dilution for FACS

Rabbit anti-c-myc polyclonal antibody (Thermo-Fisher P24484) – 1:1000 dilution for FACS

Goat anti-mouse IgG-Alexa488 conjugate (αM488, Invitrogen) – 1:500 dilution for FACS

Goat anti-rabbit IgG-allophycocyanin conjugate (Invitrogen) – 1:500 dilution for FACS

Streptavidin-phycoerythrin conjugate (SA-PE, Sigma) – 1:80 dilution for FACS

Mouse anti-biotin antibody (BTN.4, Pierce) – 1:50 dilution for FACS

15 and 50 mL conical tubes (BD Biosciences)

3% v/v formaldehyde in 10 mM PBS, pH 7.4

YDIP Elution buffer – 200mM glycine-HCl, pH 2.0

Trichloroacetic acid (Fisher Scientific)

4.2. Detection of YSD-bound membrane proteins using selective biotinylation

Recombinant antibody library screening against cells or cell lysates opens the possibility of discovering antibodies against previously unknown antigens, or selecting novel antibodies against a known membrane protein, which have unique properties (e.g. binding affinity, epitope selectivity, or signal amplification/inhibition). It follows that the detection scheme is dictated by knowledge of the antigen or lack thereof. The detection method is a key to any screen, and should be tested with the proper controls.

A strategy, that allows detection of targeted membrane proteins, particularly when searching for antibodies against unknown cell-surface targets, is cell surface-specific protein biotinylation (cells depicted in Figure 1C-i). The technique of surface biotinylation has been used extensively in proteomics to selectively purify and analyze membrane proteins [54–56]. Biotinylation reagents (EZ-link, Thermo-Fisher) come in a variety of forms, categorized by their reactivity with different organic moieties (amines, carbohydrates, sulfhydryl groups, etc.), and under the correct reaction conditions, covalently attach a single biotin molecule to available reactive groups. A common reagent in membrane proteomics is Sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin. The N – Hydroxysulfosuccinimide (NHS) ester derivatization renders the reagent water soluble (and thus membrane impermeable and selective for plasma membrane (PM) proteins) while the long-chain (LC) spacer arms reduce steric hindrance of biotin targeted labeling reagents. The NHS chemistry is reactive with primary amines, leading to the biotinylation of lysine residues and, if accessible, the amino-terminus of membrane proteins.

-

Biotinylation of membrane proteins is conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions with minor modifications. Cells at 70–80% confluence (generally >90% viability) are used to avoid biotinylating dead cells and cell debris.

NOTE – Adherent cell lines work best as they are more amenable to washing and biotinylation procedures described earlier (coatings described earlier may be used to increase adherence). Suspension lines can be used provided the cells are handled very gently during washing and centrifugation.

NOTE – T-flasks with a surface area of >75cm2 are necessary to obtain the desired number of cells and give sufficient clearance for the mechanical detachment of cells described in section 4.3. Cell number and viability are determined by Trypan blue exclusion; typical counts for a T75 at 75% confluence are 2×107 viable cells with >90% viability.

-

Weigh out Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin into a 1.5 mL microfuge tube.

NOTE – a typical working concentration is 0.5 mg/mL and approximately 5 mL of working reagent are needed for each 2.5×107 cells to be biotinylated.

Dissolve the biotinylation reagent in 1 mL of ddH2O and then dilute to working concentration in PBSCM.

Wash cells three times PBSCM to remove reactive components in the media and serum.

-

Apply the diluted biotinylation reagent for 30 minutes at room temperature. Total biotinylation times of more than 60 minutes are not recommended because, as cells begin to die and lyse, there is a potential for increased biotinylation of non-membrane proteins which can add significant background to the antibody screens.

NOTE – Time and temperature of the biotinylation reaction should be considered based on the nature of membrane proteins under study. Many membrane receptors, for example, undergo endocytosis followed by degradation or recycling to the cell surface [57, 58]. Additionally, at anytime there may be a large intracellular receptor pool, inaccessible to biotinylation [59]. One can take advantage of receptor turnover by performing biotinylation at physiological temperature (37°C), or suppress internalization by biotinylating at 4°C. Membrane protein turnover has a temporal component as well [60], with surface residence time ranging from minutes to hours. The turnover rate is often controlled by cytoplasmic proteins or extracellular ligands [61], thus allowing the manipulation of membrane protein location (and biotinylation) by genetic mutations, or the addition of small-molecule inhibitors/inducers.

-

Excess biotinylation reagent will remain unreacted in solution and must be quenched by adding a buffer containing excess reactive groups. For the NHS class of reagents, this is accomplished by washing the cells twice with PBSCMG.

NOTE – The danger of unreacted biotinylation reagent is that it could react with yeast surface proteins leading to false positive results, or with intracellular mammalian proteins upon cell lysis losing the plasma membrane selectivity. An alternate method of quenching is to add TRIS buffer to a final concentration of 50mM after step 4.3(e) below.

4.3. Preparation of detergent solubilized cell lysates

The ability of detergents to solubilize a given membrane protein varies, thus detergent selection is a critical parameter in the creation of whole-cell lysates. The literature on detergent solubility of membrane proteins is extensive due to the frequent use of detergents in membrane protein crystallization [62], expression [63], purification [64], and analysis [56, 65–67]. Proper selection of a detergent remains an empirical process: select a small subset of detergents based on literature [68] and screen the resulting cell lysates [69] using traditional proteomics tools such as immunoprecipitation, electrophoresis, western-blotting, and mass spectrometry. Our work has highlighted Triton X-100, CHAPS, Octyl glucoside, as useful reagents in the general solubilization of plasma membrane proteins for FACS-based screening [32]. Generally, non-ionic and zwitterionic detergents tend to preserve non-covalent interactions whereas ionic detergents such as SDS disrupt such interactions and lead to protein denaturation [52, 70, 71]. This property of non-ionic and zwitterionic detergents is reflected in the literature on purification of functional membrane proteins [72, 73]. Along with membrane protein functionality, the detergent chosen can also affect the multimeric association state of a given membrane protein [74–77].

-

Beginning from 4.2 (f), wash the biotinylated cells once with PBS.

NOTE – For best results, the remaining steps should be performed at 4°C or with the cells resting on a wet ice (all reagents ice-cold as well)

-

Prepare cell lysis buffer, 1.0 mL per T75 flask (if necessary, scale up proportionally by vol/cm2).

NOTE – Cell lysis buffer is PBS supplemented with detergent, EDTA, and protease inhibitors. PBS is mixed with the desired amount and type of detergent, supplemented with 2mM EDTA and frozen (−20°C) in 1.0 mL aliquots. Protease inhibitor is also stored at −20°C, as a 100x stock solution in 100 μL aliquots. The complete lysis buffer is made by thawing a 1.0 mL aliquot of PBS/detergent/EDTA and adding 100 μL of thawed protease inhibitor cocktail.

Add the cell lysis buffer to the cells and rotate the flask to coat the cells (Figure 1C-i).

Tilt the flask to one side, and using a sterile cell scraper, thoroughly scrape the cells into the lysis buffer. Tilt the flask in the opposite direction, letting the lysis buffer run to the opposite side, and scrape again. Repeat this process three times.

Allow the flask to rest with one corner elevated so that the cell suspension drains into the bottom. The solution should be visually cloudy with lysed cells. Collect the cell lysate using a micropipette, and transfer to a clean 1.5 mL microfuge tube (Figure 1C-ii).

Incubate at 4°C, rotating for 15 minutes.

Centrifuge at 4°C, 18,000g in a microfuge for 30 minutes. Insoluble proteins and cell debris will form a small pellet in the bottom of the tube.

-

Collect the supernatant, being careful not to disturb the pellet, and store at 4°C until use. For best results, cell lysates should be used as soon as possible after creation.

NOTE – Detergent solubilized membrane proteins may aggregate or denature over time [62]. Anecdotally, we were able to freeze freshly made RBE4 cell lysates at −20°C and later use them in the FACS experiments outlined below. However, HEK293 lysates lost all binding activity with positive control YSD anti-transferrin receptor antibodies after freezing, and signal deteriorated within 48hrs when stored at 4°C (unpublished data).

4.4. FACS-based screening of YSD libraries using whole-cell lysates

-

For FACS, yeast cells expressing the scFv library are collected in 10-fold excess of the library size, pelleted by centrifugation at 2,500g for 5 min, and washed twice in PBSA by resuspending the pellet in fresh buffer.

NOTE – To facilitate the screening process with antibody libraries with >109 diversity, MACS (Magnetic-activated cell sorting) can be used for the initial round of screening. Detailed protocols to screen a human non-immune scFv library using soluble antigens have been previously published [38, 39, 78]. These procedures can be adapted to MP-targeted antibody screening simply by replacing the antigen solution with cell lysates.

NOTE – All of the following washing and labeling steps were performed at 4°C.

-

Incubate yeast with PM-biotinylated cell lysate (explained in sections 4.2 and 4.3), supplemented with 1 mM biotin, rotating overnight (Figure 1C-iii).

NOTE – Excess free biotin is added to avoid selection of biotin binding scFvs. As a starting point, use 1 mL of cell lysates made from at least 5×107 mammalian cells (>2 mg/mL total protein concentration) to incubate with 1×107 yeast cells. This is a conservative estimate, assuming 5×107 cells in 1 mL total volume, proteins expressed at 104 copies per cell would have a concentration of ~1 nM. Here, the concentration of protein, not the absolute amount, is key; antigen depletion is not a concern since the library contains many members with unique antigen specificities, but the frequency of each individual member is low in early screening rounds. Given the size of combinatorial libraries, we typically incubate 5×109 yeast cells in 7 – 8 mL of cell lysate. Assuming 2mg/mL lysate concentration, 14 – 16 mg of total protein is needed in the first round to maximize the diversity of the isolated scFvs. Lowering the volume or diluting the cell lysates will bias the selection towards antibodies with high affinity or those that bind to abundant antigens.

-

Wash the incubated yeast twice with PBSD (1 mL per 5×107 yeast), then once with PBSA, aspirating to remove wash buffer.

NOTE – At this point, the yeast may be aspirated very easily. Refer to section 2.3 for the physical effects of detergents on yeast cells.

Mix the yeast with primary detection reagents (recognizing biotin and c-myc, respectively) diluted in PBSA (50 μL volume per 106 yeast cells), and incubate on ice for 30 minutes.

Wash the yeast twice with PBSA, aspirating to finish

-

Mix the yeast with secondary detection reagents (fluorescently labeled antibodies) diluted in PBSA (50 μL volume per 106 yeast cells), and incubate on ice for 30 minutes.

NOTE – Detection of biotinylated membrane proteins is usually accomplished by avidin/neutravidin/streptavidin conjugated to a fluorescent probe (e.g. streptavidin-PE), and detection of scFv displaying yeast accomplished with anti-c-myc antibodies (Figure 1A and Figure 2B). As with all YSD screening, there exists the potential to isolate scFv that bind these primary labeling reagents rather than biotinylated antigen [79]. This problem can be solved by alternating primary detection reagents with each screening round. Our lab has used an anti-biotin antibody as an alternative to SA-PE. We have also used a polyclonal rabbit anti-c-myc as an alternative to the monoclonal mouse 9E10. Allophycocyanin (or Alexa647) and Alex488 conjugated secondary antibodies work nicely together since their emission spectra are not convoluted by the flow cytometer and thus the signals do not require compensation. See material list above for detection reagent details.

-

Yeast are sorted on the flow cytometer (e.g. BD FACSAria), directly into sterile SD-CAA medium. Recovered yeast cells are grown overnight at 30°C in SD-CAA supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/mL) until the OD600 reaches 1.0 (Figure 1C-iv).

NOTE – Ref. [80] provides a discussion of optimal gating strategies for recoveries yeast by FACS h. The entire process in this section is repeated to enrich for yeast-displayed scFvs with desired characteristics (Figure 1C-v).

4.5. Screening for a pre-determined membrane target

The membrane binding pools isolated using protocol in section 4.4 can be further screened to identify antibodies against a specific target. In principle, this procedure can also be combined with the clones isolated from yeast biopanning described in section 3.5. To screen for antibodies recognizing a known MP of interest, a second monoclonal antibody against the target is required. Since this antibody is used to detect the presence of antigen-scFv binding, the scFvs isolated from the screen will have different binding epitopes than the monoclonal antibody used for detection. Therefore, the detection antibody should be cautiously chosen so that it does not mask the epitope of interest. An example would be to use an antibody that recognizes the target MP cytosolic domain while searching for antibodies against the target MP extracellular domain [32]. In this way one could raise a panel of scFv recognizing a known MP target using cell lysates as antigen sources.

The membrane binding pool isolated from one or two rounds of MACS, FACS or biopanning is first incubated with freshly prepared PM-biotinylated cell lysate, overnight at 4°C. As in section 4.4, use 1 mL of cell lysates (>2 mg/mL total protein concentration) to incubate 107 yeast cells.

Wash the incubated yeast twice with PBSD (1 mL per 5×107 yeast), then once with PBSA, aspirating to finish.

Incubate with a monoclonal antibody against the target MP antigen, diluted in PBSA (50 μL volume per 106 yeast cells) for 30 minutes on ice.

Wash the yeast twice with PBSA, aspirating to finish

Mix the yeast with SA-PE and a secondary detection reagent (fluorescently labeled against the primary antibody from part (c) ) diluted in PBSA (50 μL volume per 106 yeast cells), and incubate on ice for 30 minutes.

Sort yeast using FACS as in section 4.4, making sure to gate the population that is labeled with both SA-PE (lysate binding) and αM488 (target MP antigen). This will avoid isolating clones that bind to secondary reagents, since alternating the secondary reagent as described in the notes of 4.4(g), is not feasible in many cases.

4.6. Characterization of antibody-antigen binding using cell lysates

In this protocol, serial dilutions of cell lysates are used to characterize the antibody binding affinity directly on the surface of yeast. Although this protocol is most useful to determine the relative affinities of two or more antibody clones that bind to a single target antigen as shown in Figure 2B, absolute affinities can be determined by measuring the target antigen concentration in cell lysates using methods such as ELISA or quantifying the expression level of target antigen using commercially available kits such as the Quantum Simply Cellular ™ kit from Bang’s Labs (Fishers, IN). However, as long as the antibodies bind to the same antigen, one can compare the affinities of a series of antibodies simply by using dilutions of cell lysates, eliminating the need for heterologous expression or purification of membrane protein antigens or the scFvs themselves [33].

Dilutions of the biotinylated cell lysates (> 2 mg/mL total protein concentration) are prepared in PBSD. Since the antigen concentration is unknown in many cases, make dilutions by adding an appropriate amount of buffer to 0.5 mL of cell lysate. For example, to prepare 10-fold diluted solution, add 4.5 mL of PBSD. See ref. [39] for a guideline on preparing serial dilutions for a equilibrium binding titration measurement. At minimum, a buffer only control should be included to control for cellular autofluorescence as well as any detergent-promoted binding of antibody reagents. A more rigorous approach would be to use a yeast-displayed scFv having no reactivity towards cell lysate.

-

Approximately 5×105 yeast cells displaying scFv clones are aliquoted into 15 mL or 50 mL conical tubes containing serial dilutions of the cell lysate, and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with rotation.

NOTE – All of the subsequent washing and labeling steps are performed at 4°C

Centrifuge the yeast at 2,500g for 10 min and resuspend the pellet in 1 mL PBSD. Transfer to a clean microfuge tube.

Wash the yeast once with PBSA and then incubate with 50 μL of mouse anti-c-myc antibody for 30 minutes.

Wash the yeast once in PBSA and incubate with αM488 and SA-PE secondary antibodies, in 50 μL PBSA, for 20 minutes.

Analyze the samples at each lysate dilution using a flow cytometer (e.g. Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur) by collecting fluorescence data on the relevant channels for at least 10,000 yeast events. Visualize log-normal fluorescence data using a bivariate plot of scFv expression (c-myc+) versus cell lysate binding (biotin+) (Figure 2B, left and middle Panels). Draw a logical gate around the c-myc+ events and quantify the geometric mean fluorescence values in the biotin+ direction of the gated, lysate-binding population (MFIdisp) (Figure 2B, gated population in middle panel). Similarly analyze the negative control samples (lysate buffer only or irrelevant scFv) and determine the MFIneg (Figure 2B, gated population in left panel). Calculate the fluorescence due to binding as MFIbind = MFIdisp − MFIneg.

-

Use the calculated MFIbind versus experimental lysate concentration ([%L]) data to fit the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd in units of % lysate) and MFIrange according to the following monovalent binding model: MFIbind= (MFIrange × [%L])/([%L] + Kd). The fitted parameter MFIrange is the difference between the MFI at ligand saturation and MFIneg. Fitting is readily accomplished using a non-linear regression routine (such as the one included in GraphPad Prism®) to minimize the sum-of-squares errors as a function of the fit parameters, the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd), and MFIrange. To compare the relative binding capacity of several scFvs that bind to the same target, simply compare the Kd values derived from the above analysis. To plot data in the typical “fraction bound” format, simply divide the experimentally derived MFIbind by MFIrange. Figure 2B, right panel, shows some representative results from this analysis. References [81] and [39] contain additional details on the modeling and analysis of this type of data.

NOTE – The equilibrium binding affinities computed in the above analysis are strictly “apparent” owing to potential avidity affects with multimeric antigens and more general detergent affects on the binding equilibrium between scFvs and antigens. Importantly, one can still elucidate relative affinities for a subset of scFvs, which is valuable for identifying clones of interest to be used in YDIP (section 4.7 below) or for subcloning, purification, and validation as soluble scFv proteins.

4.7. Identification of target membrane proteins using YDIP

Since antibodies isolated from whole cell or cell lysate-based methods can bind to any accessible membrane protein, it is critical to identify and characterize the target antigen. Yeast surface display provides another unique solution to this problem since yeast cells expressing scFvs can be used as affinity reagents to capture and isolate target antigens by a method termed yeast display immunoprecipitation (YDIP) [33]. Importantly, the experimental conditions used for antibody screening described in sections 4.2 - 4.4. such as the choice of detergent, can be used without further optimization, greatly facilitating the target characterization process [32]. Moreover, this protocol can also be applied to antibody clones isolated by biopanning described in section 3.5. to identify the target antigens [30, 33]. This section describes the protocol for YDIP followed by target antigen identification using mass spectrometry.

-

3×109 yeast cells, grown and induced from a single colony (displaying an scFv clone) are collected by centrifugation at 2,500g for 10 minutes. The yeast cells are washed once with 5 mL of PBSA and fixed by incubation in 10 mL of 3% v/v formaldehyde in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature.

NOTE – Formaldehyde fixation reduces contamination with yeast proteins in the final elution product.

Fixed yeast cells are washed with 5 mL of PBSA and divided into eight reactions using 1.5 mL microfuge tubes.

-

1 mL cell lysate (containing ~ 2mg of total protein) is added to each tube and incubated overnight at 4°C with rotation. (Figure 1C-vi).

NOTE – In this case, it is not necessary for the cells to be biotinylated before creating the cell lysate.

Yeast cells are pelleted by centrifugation at 18,000g for 1 minute and each tube is washed three times in 1 mL of wash buffer.

NOTE – Make sure to aspirate all buffer after each wash to ensure removal of non-specific proteins in the lysate.

To elute the antigen from yeast cells, 70 μL of YDIP elution buffer is added in four of the eight tubes of pelleted yeast cells and vortexed for 30 seconds to completely resuspend the pellet. The elution mixture is incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. (Figure 1C-vii).

Centrifuge at 18,000g for 1 minute then, carefully collect the supernatant and serially transfer to the other four tubes with pelleted YDIP yeast cells.

To concentrate the antigen, all 4 product pools created each by serial elution of two tubes are pooled together (~ 280 μL). The combined elution product is precipitated at 4°C for 2 hrs by the addition of trichloroacetic acid to a final concentration of 13% (w/v).

Collect protein by centrifuging at 12,000g for 15 min at 4°C. The pelleted protein is then dissolved in 2X Laemmli sample buffer [82] for separation by SDS-PAGE (8% separation gel). If the cell lysate has been biotinylated, anti-biotin antibody (BTN.4) can be used for Western blotting to determine antigen size (Figure 2C).

The gel is stained using colloidal coomassie [83] to visualize the eluted proteins.

In-gel digestion is performed using standard protocols [84] to sequence the digested peptide from the target antigen using tandem mass spectrometry.

5. SUMMARY AND OUTLOOK

The above methods constitute a powerful and flexible set of tools for researchers looking to isolate and engineer antibodies against MPs. We took a modular approach, building in additional functionality to deal with MPs into the well established, YSD-based antibody engineering platform. As technology for the isolation and characterization of MPs continues to advance, we expect the utility of this system to expand. In particular, the development of novel detergents [85–88] should allow the extension of our methods to previously untenable targets like G-Protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and ion channels. Also potentially useful are recent studies in site-specific protein tagging [89–91], and the development of heterologous mammalian expression systems [92–94] for complex plasma membrane proteins. In conclusion, we anticipate the approaches detailed here will help fill an important technological void by increasing researchers’ capabilities for engineering antibodies against membrane-resident antigens.

Acknowledgments

This methodological developments detailed in this report were supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants NS052649, EY018506, and NS071513.

Abbreviations

- MAb

monoclonal antibody

- scFv

single chain variable fragment

- MP

membrane protein

- OD

optical density

- YSD

yeast surface display

- PM

plasma membrane

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- MACS

magnetic-activated cell sorting

- YDIP

yeast display immunoprecipitation

- SA-PE

Streptavidin-Phycoerythrin

- TfR

Transferrin Receptor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Yildirim MA, et al. Drug-target network. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(10):1119–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reichert JM. Antibody-based therapeutics to watch in 2011. MAbs. 2011;3(1) doi: 10.4161/mabs.3.1.13895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reichert JM. Antibodies to watch in 2010. MAbs. 2010;2(1):84–100. doi: 10.4161/mabs.2.1.10677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reichert JM. Monoclonal Antibodies as Innovative Therapeutics. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. 2008;9:423–430. doi: 10.2174/138920108786786358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson AL, Dhimolea E, Reichert JM. Development trends for human monoclonal antibody therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9(10):767–774. doi: 10.1038/nrd3229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoogenboom HR. Selecting and screening recombinant antibody libraries. Nat Biotech. 2005;23(9):1105–1116. doi: 10.1038/nbt1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trepel M, Pasqualini R, Arap W. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press; 2008. Chapter 4: Screening Phage-Display Peptide Libraries for Vascular Targeted Peptides; pp. 83–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cattaneo A. Tanezumab, a recombinant humanized mAb against nerve growth factor for the treatment of acute and chronic pain. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2010;12(1):94–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiner GJ. Rituximab: mechanism of action. Semin Hematol. 2010;47(2):115–23. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alley SC, Okeley NM, Senter PD. Antibody-drug conjugates: targeted drug delivery for cancer. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2010;14(4):529–537. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.06.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polson AG, et al. Anti-CD22-MCC-DM1: an antibody-drug conjugate with a stable linker for the treatment of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Leukemia. 2010;24(9):1566–73. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta A, et al. Conformation state-sensitive antibodies to G-protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(8):5116–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609254200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu X, et al. Rational Design of Envelope Identifies Broadly Neutralizing Human Monoclonal Antibodies to HIV-1. Science. 2010;329(5993):856–861. doi: 10.1126/science.1187659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White SH, Wimley WC. Membrane Protein Folding and Stability: Physical Principles. Annual Review of Biophysics and Biomolecular Structure. 1999;28(1):319–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lundstrom K, et al. Structural genomics on membrane proteins: comparison of more than 100 GPCRs in 3 expression systems. Journal of Structural and Functional Genomics. 2006;7(2):77–91. doi: 10.1007/s10969-006-9011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green LL. Antibody engineering via genetic engineering of the mouse: XenoMouse strains are a vehicle for the facile generation of therapeutic human monoclonal antibodies. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1999;231(1–2):11–23. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(99)00137-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jakobovits A, et al. From XenoMouse technology to panitumumab, the first fully human antibody product from transgenic mice. Nat Biotech. 2007;25(10):1134–1143. doi: 10.1038/nbt1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dreyer AM, et al. An efficient system to generate monoclonal antibodies against membrane-associated proteins by immunisation with antigen-expressing mammalian cells. BMC Biotechnol. 2010;10(1):87. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-10-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasqualini R, Ruoslahti E. Organ targeting In vivo using phage display peptide libraries. Nature. 1996;380(6572):364–366. doi: 10.1038/380364a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valadon P, et al. Screening phage display libraries for organ-specific vascular immunotargeting in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(2):407–412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506938103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zahid M, et al. Identification of a Cardiac Specific Protein Transduction Domain by In Vivo Biopanning Using a M13 Phage Peptide Display Library in Mice. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(8):e12252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Essler M, Ruoslahti E. Molecular specialization of breast vasculature: A breast-homing phage-displayed peptide binds to aminopeptidase P in breast vasculature. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(4):2252–2257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251687998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krag DN, et al. Selection of Tumor-binding Ligands in Cancer Patients with Phage Display Libraries. Cancer Research. 2006;66(15):7724–7733. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore SJ, Olsen Mark J, Cochran Jennifer R, Cochran Frank V. Cell surface Display Systems for Protein Engineering. In: Park SJ, Cochran Jennifer R, editors. Protein Engineering and Design. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2009. pp. 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dove A. Antibody production branches out. Nat Meth. 2009;6(11):851–856. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boder ET, Wittrup KD. Yeast surface display for screening combinatorial polypeptide libraries. Nat Biotech. 1997;15(6):553–557. doi: 10.1038/nbt0697-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benatuil L, et al. An improved yeast transformation method for the generation of very large human antibody libraries. Protein Engineering Design and Selection. 2010;23(4):155–159. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzq002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowley DR, et al. Antigen selection from an HIV-1 immune antibody library displayed on yeast yields many novel antibodies compared to selection from the same library displayed on phage. Protein Engineering Design and Selection. 2007;20(2):81–90. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzl057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang XX, Shusta EV. The use of scFv-displaying yeast in mammalian cell surface selections. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2005;304(1–2):30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang XX, Cho YK, Shusta EV. Mining a yeast library for brain endothelial cell-binding antibodies. Nat Meth. 2007;4(2):143–145. doi: 10.1038/nmeth993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richman SA, et al. Development of a novel strategy for engineering high-affinity proteins by yeast display. Protein Engineering Design and Selection. 2006;19(6):255–264. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzl008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho YK, Shusta EV. Antibody library screens using detergent-solubilized mammalian cell lysates as antigen sources. Protein Engineering Design and Selection. 2010;23(7):567–577. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzq029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho YK, et al. A yeast display immunoprecipitation method for efficient isolation and characterization of antigens. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2009;341(1–2):117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gai SA, Wittrup KD. Yeast surface display for protein engineering and characterization. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2007;17(4):467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sikorski RS, Hieter P. A System of Shuttle Vectors and Yeast Host Strains Designed for Efficient Manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122(1):19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hackel BJ, Kapila A, Dane Wittrup K. Picomolar Affinity Fibronectin Domains Engineered Utilizing Loop Length Diversity, Recursive Mutagenesis, and Loop Shuffling. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2008;381(5):1238–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weaver-Feldhaus JM, et al. Yeast mating for combinatorial Fab library generation and surface display. FEBS Lett. 2004;564(1–2):24–34. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00309-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feldhaus MJ, et al. Flow-cytometric isolation of human antibodies from a nonimmune Saccharomyces cerevisiae surface display library. Nat Biotech. 2003;21(2):163–170. doi: 10.1038/nbt785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chao G, et al. Isolating and engineering human antibodies using yeast surface display. Nat Protocols. 2006;1(2):755–768. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pepper LR, et al. A Decade of Yeast Surface Display Technology: Where Are We Now? Combinatorial Chemistry & High Throughput Screening. 2008;11(2):127–134. doi: 10.2174/138620708783744516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang D, Gore PR, Shusta EV. Increasing yeast secretion of heterologous proteins by regulating expression rates and post-secretory loss. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2008;101(6):1264–1275. doi: 10.1002/bit.22019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shusta EV, et al. Yeast polypeptide fusion surface display levels predict thermal stability and soluble secretion efficiency. J Mol Biol. 1999;292(5):949–56. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laouar L, Lowe KC, Mulligan BJ. Yeast responses to nonionic surfactants. Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 1996;18(6):433–438. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miozzari GF, Niederberger P, Hütter R. Permeabilization of microorganisms by Triton X-100. Analytical Biochemistry. 1978;90(1):220–233. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu X, et al. Combinatorial libraries against libraries for selecting neoepitope activation-specific antibodies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107(14):6252–6257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914358107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moelleken K, Hegemann JH. The Chlamydia outer membrane protein OmcB is required for adhesion and exhibits biovar-specific differences in glycosaminoglycan binding. Molecular Microbiology. 2008;67(2):403–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06050.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mölleken K, Schmidt E, Hegemann JH. Members of the Pmp protein family of Chlamydia pneumoniae mediate adhesion to human cells via short repetitive peptide motifs. Molecular Microbiology. 2010;78(4):1004–1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tur MK, et al. Selection of scFv phages on intact cells under low pH conditions leads to a significant loss of insert-free phages. Biotechniques. 2001;30(2):404–8. 410, 412–3. doi: 10.2144/01302rr04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ackerman M, et al. Highly avid magnetic bead capture: An efficient selection method for de novo protein engineering utilizing yeast surface display. Biotechnology Progress. 2009;25(3):774–783. doi: 10.1002/btpr.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perdue JF, et al. The biochemical characterization of detergent-solubilized insulin-like growth factor II receptors from rat placenta. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1983;258(12):7800–7811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seligman PA, Schleicher RB, Allen RH. Isolation and characterization of the transferrin receptor from human placenta. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1979;254(20):9943–9946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin S-H, Guidotti G. Chapter 35 Purification of Membrane Proteins. In: Richard RB, Murray PD, editors. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press; 2009. pp. 619–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bowley DR, et al. Libraries against libraries for combinatorial selection of replicating antigen-antibody pairs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(5):1380–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812291106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Altin JG, Pagler EB. A One-Step Procedure for Biotinylation and Chemical Cross-Linking of Lymphocyte Surface and Intracellular Membrane-Associated Molecules. Analytical Biochemistry. 1995;224(1):382–389. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hurley WL, Finkelstein E, Holst BD. Identification of surface proteins on bovine leukocytes by a biotin-avidin protein blotting technique. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1985;85(1):195–202. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(85)90287-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jang JH, Hanash S. Profiling of the cell surface proteome. Proteomics. 2003;3(10):1947–1954. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lao BJ, et al. Inhibition of transferrin iron release increases in vitro drug carrier efficacy. Journal of Controlled Release. 2007;117(3):403–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van Gelder W, et al. Iron Uptake in Blood-Brain Barrier Endothelial Cells Cultured in Iron-Depleted and Iron-Enriched Media. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1998;71(3):1134–1140. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71031134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raub TJ, Newton CR. Recycling kinetics and transcytosis of transferrin in primary cultures of bovine brain microvessel endothelial cells. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 1991;149(1):141–151. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041490118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilson MH, Limbird LE. Mechanisms Regulating the Cell Surface Residence Time of the α2A-Adrenergic Receptor. Biochemistry. 2000;39(4):693–700. doi: 10.1021/bi9920275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dinneen JL, Ceresa BP. Continual Expression of Rab5(Q79L) Causes a Ligand-Independent EGFR Internalization and Diminishes EGFR Activity. Traffic. 2004;5(8):606–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9219.2004.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Privé GG. Detergents for the stabilization and crystallization of membrane proteins. Methods. 2007;41(4):388–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Klammt C, et al. Evaluation of detergents for the soluble expression of α-helical and β-barrel-type integral membrane proteins by a preparative scale individual cell-free expression system. FEBS Journal. 2005;272(23):6024–6038. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Macdonald JL, Pike LJ. A simplified method for the preparation of detergent-free lipid rafts. J Lipid Res. 2005;46(5):1061–7. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D400041-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schuck S, et al. Resistance of cell membranes to different detergents. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(10):5795–5800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631579100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lingwood D, Simons K. Detergent resistance as a tool in membrane research. Nat Protocols. 2007;2(9):2159–2165. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Braun R, et al. Two-dimensional electrophoresis of membrane proteins. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2007;389(4):1033–1045. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1514-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Linke D. Chapter 34 Detergents: An Overview. In: Richard RB, Murray PD, editors. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press; 2009. pp. 603–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hjelmeland LM, Chrambach A, William BJ. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press; 1984. Chapter 16: Solubilization of functional membrane proteins; pp. 305–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]