Abstract

Recipients of solitary liver and kidney transplantations are living longer, increasing their risk of long-term complications such as recurrent hepatitis C virus (HCV) and drug-induced nephrotoxicity. These complications may require retransplantation. Since the adoption of the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD), the number of simultaneous liver-kidney transplants (SLK) has increased. However, there are no standardized criteria for organ allocation for SLK candidates. The aims of this study are to retrospectively compare recipient and graft survival for liver transplant alone (LTA) to SLK, kidney after liver transplantation (KALT) and liver after kidney transplantation (LAKT) and identify independent risk factors that affect recipient and graft survival. The United Network for Organ Sharing/Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (UNOS/OPTN) database was queried for adult LTA (66,026), SLK (2,327), KALT (1,738) and LAKT (242) from 1988 to 2007. After adjusting for potential confounding demographic and clinical variables, there was no difference in recipient mortality between LTA and SLK (p=0.024). However, there was a 15% decreased risk of graft loss in SLK compared to LTA [Hazard Ratio (HR) = 0.85, p<0.0001]. Recipient and graft survival in SLK was higher compared to both KALT (p<0.0001) and LAKT (p<0.0001). Recipient age ≥65 years, male, black, and HCV/diabetes mellitus (DM) status as well as donor age ≥60 years, serum creatinine ≥2 mg/dL, cold ischemia time (CIT) >12 hours and warm ischemia time (WIT) >60 minutes were all identified as independent negative predictors of recipient mortality and graft loss. Although the recent increase in SLK performed each year effectively decreases the number of potential donor kidneys available to patients with ESRD awaiting kidney transplantation, SLK in patients with ESLD and ESRD is justified due to lower risk of graft loss in SLK compared to LTA as well as superior recipient and graft survival compared to serial liver-kidney transplantation.

INTRODUCTION

Improvement in post-transplant management, particularly immunosuppressive therapy, has led to a dramatic increase in patient survival following solid organ transplantation. Specifically, immunosuppressive therapy with the calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) cyclosporine and tacrolimus has enhanced survival after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLTX).1,2 Despite their associated improved survival, CNIs are inherently nephrotoxic, and often cited as the main cause of chronic renal failure (CRF) following OLTX.3–7 In the first six months following OLTX, CNIs have been associated with nearly a 30% decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR).3 Moreover, CNIs contribute to development of CRF in approximately 18% of OLTX patients after 13 years, including 9.5% who progress to end stage renal disease (ESRD).3 Because nephrotoxicity may lead to the discontinuation of CNIs, less effective immunosuppressive agents are used, which may result in more frequent liver and renal graft dysfunction. For these reasons, CNI toxicity and the acceleration of underlying liver and renal disease may necessitate subsequent liver and/or kidney retransplantation.

Since the implementation of the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) in 2002 as an objective allocation system, priority has shifted to end-stage liver disease (ESLD) patients with renal insufficiency. This shift in priority has led to a rapid albeit unintentional increase in the number of simultaneous liver-kidney transplants (SLK). Specifically, since 2001, not only did the number of SLK increase by more than 300%, but the proportion of SLK to overall number of OLTX more than doubled from 2.38% in 2001 to 5.5% in 2006.8 Although significant renal impairment had previously been considered a contraindication for OLTX, SLK has become a well-established therapeutic option for endstage renal and liver disease since the first SLK performed by Margreiter et al in 1984.9 Few studies have analyzed liver graft survival following SLK compared to liver transplant alone (LTA); however, there is an increasing number of studies that have reviewed renal graft survival, which have produced mixed results.10–16 There is compelling evidence supporting the theory for an immunoprotective role assumed by the transplanted liver in preventing renal allograft rejection in SLK from the same donor, but there is no definitive evidence demonstrating improved recipient or graft survival. Despite the significant increase in the number of SLK performed each year, there are currently no standardized criteria for organ allocation in SLK candidates. The current national organ shortage coupled with the increasing demand for liver and kidney transplantation as well as the increasing number of patients undergoing transplantation magnify the need for robust data on outcomes of SLK to appropriately allocate scarce resources and to optimize post-transplant care.

The principal aim of this study was to compare recipient and liver graft survival in recipients of LTA to those who underwent SLK, kidney after liver transplant (KALT) and liver after kidney transplant (LAKT) based on the UNOS/Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) database. A secondary aim of this study was to identify independent risk factors that affect recipient and graft survival.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The UNOS/OPTN database was queried for all first-time adult LTA, SLK, KALT, and LAKT from January 1, 1988 to December 31, 2007 with at least 2 years of follow-up. Pediatric recipients and recipients of other organs were excluded from the analysis. SLK was defined as any combination of liver and kidney transplantation occurring 2 days or less from the date of the initial transplantation. Serial transplantations were defined as any combination of liver and kidney transplantation occurring after 2 days from the initial transplantation. Various recipient and donor demographic and clinical characteristics were identified, which included recipient age, sex, ethnicity, hepatitis C virus (HCV) and diabetes mellitus (DM) status, pre-transplant serum creatinine, indication for liver transplant, time on waitlist, time between serial transplants, cold ischemia time (CIT), warm ischemia time (WIT) as well as donor age, ethnicity and graft type. Patients were identified from the liver file and then matched to the kidney file to ensure accuracy.

Cox regression models were used to estimate recipient and graft survival rates to construct Kaplan-Meier (KM) survival curves for both recipient and graft survival. Survival was calculated from the time of liver transplant. A time-dependent covariate Cox proportionalhazards regression model was used in the KALT arm to reflect that patients were in the LTA arm until they had a kidney transplant at which time they moved from the LTA arm to the KALT arm. Multivariate Cox regression models were used to assess the association of recipient mortality and graft loss with different demographic and clinical variables. All patient deaths were considered graft failure regardless of graft status at the time of patient death. Therefore, graft failure was defined as patient death with the original graft or retransplantation of the original graft, whichever came first. Cumulative incidence probabilities were calculated for both death, defined as the probability of death with the first liver transplant still functioning prior to time ‘t’, and retransplantation, defined as the probability of receiving a new liver prior to time ‘t’. In the setting of a large national database, p-value <0.01 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software, version 9.2. This protocol was reviewed and approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Recipient Demographics

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the four transplantation groups are shown in Table 1. A total of 70,333 liver transplants were analyzed, which included LTA (n=66,026), SLK (n=2,327), KALT (n=1,738) and LAKT (n=242). Nearly 50% of all liver transplants were between the ages of 50 and 64; however, the largest age group for KALT was 35–49 years (45.4%). Male recipients were more common throughout each of the transplant groups, comprising 62.8% of total liver transplants. With regard to ethnicity, Caucasian recipients were more common throughout each of the transplant groups, comprising 76.7% of total liver transplants. Although the majority of all transplant recipients were HCV-negative (38.7%), 30.5% were HCV-positive while 30.8% had no available HCV status. Similarly, the majority of all transplant recipients were DM-negative (63.7%), 15.2% were DM-positive and 21.2% had no available DM status. HCV with cirrhosis was the most common indication for liver transplant throughout each transplant subgroup comprising 24.5% of total liver transplants. Nearly all organs were obtained from deceased donors (96.7%). A large majority of transplant recipients were on the liver waitlist less than 1 year ranging from 80.6% (LAKT) to 83.4% (KALT). Similarly, many transplant recipients were on the kidney waitlist less than 1 year ranging from 45.9% (LAKT) to 73.8% (SLK). The majority of serial transplants were completed more than 5 years after the initial organ transplant, namely 56.3% for KALT and 53.3% for LAKT. A serum creatinine level of <2 mg/dL at time of transplant was present in as many as 86.9% of LTA recipients and as few as 13.2% of SLK recipients. On the other hand, 75% of KALT recipients had a pre-transplant serum creatinine <2 mg/dL while 69% of LAKT recipients had a pre-transplant serum creatinine of ≥2 mg/dL.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics for LTA, SLK, KALT and LAKT.

| CHARACTERISTIC | LTA (n = 66,026) |

SLK (n = 2,327) |

KALT (n = 1,738) |

LAKT (n = 242) |

TOTALS (n = 70,333) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGE, n (%) | ||||||

| 18–34 | 5,206 (7.9) | 143 (6.2) | 194 (11.2) | 39 (16.1) | 5,582 (7.9) | |

| 35–49 | 22,698 (34.4) | 629 (27.0) | 789 (45.4) | 95 (39.3) | 24,211 (34.4) | |

| 50–64 | 32,447 (49.1) | 1,346 (57.8) | 703 (40.5) | 98 (40.5) | 34,594 (49.2) | |

| ≥ 65 | 5,675 (8.6) | 209 (9.0) | 52 (3.0) | 10 (4.1) | 5,946 (8.5) | |

| SEX, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 41,349 (62.6) | 1,525 (65.5) | 1,146 (65.9) | 156 (64.5) | 44,176 (62.8) | |

| Female | 24,677 (37.4) | 802 (34.5) | 592(34.1) | 86 (35.5) | 26,157 (37.2) | |

| ETHNICITY, n (%) | ||||||

| Caucasian | 50,826 (77.0) | 1,555 (66.8) | 1,367 (78.7) | 176 (72.7) | 53,924 (76.7) | |

| Hispanic | 7,164 (10.9) | 356 (15.3) | 172 (9.9) | 14 (5.8) | 7,706 (11.0) | |

| Black | 4,816 (7.3) | 288 (12.4) | 136 (7.8) | 36 (14.9) | 5,276 (7.5) | |

| HCV STATUS, n (%) | ||||||

| HCV-positive | 20,216 (30.6) | 756 (32.5) | 417 (24.0) | 80 (33.1) | 21,469 (30.5) | |

| HCV-negative | 25,466 (38.6) | 1,123 (48.3) | 510 (29.3) | 112 (46.3) | 27,211 (38.7) | |

| unknown | 20,344 (30.8) | 448 (19.3) | 811 (46.7) | 50 (20.7) | 21,653 (30.8) | |

| DM STATUS, n (%) | ||||||

| DM-positive | 9,550 (14.5) | 753 (32.4) | 300 (17.3) | 55 (22.7) | 10,658 (15.2) | |

| DM-negative | 42,594 (64.5) | 1,295 (55.7) | 722 (41.5) | 162 (66.9) | 44,773 (63.7) | |

| unknown | 13,882 (21.0) | 279 (12.0) | 716 (41.2) | 25 (10.3) | 14,902 (21.2) | |

| HCV-positive/DM-positive, n (%) | 3,334 (5.1) | 298 (12.8) | 110 (6.3) | 21 (8.7) | 3,763 (5.4) | |

| HCV-positive/DM-negative, n (%) | 16,104 (24.4) | 440 (18.9) | 278 (16.0) | 55 (22.7) | 16,877 (24.0) | |

| HCV-negative/DM-positive, n (%) | 4,683 (7.1) | 382 (16.4) | 138 (7.9) | 22 (9.1) | 5,225 (7.4) | |

| HCV-negative/DM-negative, n (%) | 19,679 (29.8) | 703 (30.2) | 331 (19.0) | 85 (35.1) | 20,798 (29.6) | |

| HCV/DM unknown, n (%) | 22,226 (33.7) | 504 (21.7) | 881 (50.7) | 59 (24.4) | 23,670 (33.7) | |

| INDICATION FOR LIVER TX, n (%) | ||||||

| HCV with cirrhosis | 16,088 (24.4) | 634 (27.3) | 411 (23.7) | 77 (31.8) | 17,210 (24.5) | |

| EtOH cirrhosis | 9,361 (14.2) | 389 (16.7) | 274 (15.8) | 4 (1.7) | 10,028 (14.3) | |

| Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC) | 4,476 (6.8) | 47 (2.0) | 125 (7.2) | 1 (0.4) | 4,649 (6.6)* | |

| Alcoholic cirrhosis with HCV | 3,993 (6.1) | 113 (4.9) | 90 (5.2) | 1 (0.4) | 4,197 (6.0) | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and cirrhosis | 3,208 (4.9) | 70 (3.0) | 28 (1.6) | 6 (2.5) | 3,312 (4.7) | |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) | 4,100 (6.2) | 61 (2.6) | 103 (5.9) | 3 (1.2) | 4,267 (6.1) | |

| Cryptogenic cirrhosis | 3,302 (5.0) | 167 (7.2) | 122 (7.0) | 7 (2.9) | 3,598 (5.1) | |

| TIME ON WAITING LIST, n (%) | ||||||

| < 1 year | ||||||

| for liver transplant | 53,550 (81.1) | 1,918 (82.4) | 1,449 (83.4) | 196 (80.6) | 57,112 (81.2) | |

| for kidney transplant | 0 | 1,717 (73.8) | 1,014 (58.3) | 111 (45.9) | 2,842 (4.0) | |

| 1–3 years | ||||||

| for liver transplant | 10,082 (15.3) | 320 (13.7) | 245 (14.0) | 38 (15.3) | 10,682 (15.2) | |

| for kidney transplant | 0 | 142 (6.1) | 481 (27.7) | 78 (32.2) | 701 (1.0) | |

| > 3 years | ||||||

| for liver transplant | 2,394 (3.6) | 91 (3.9) | 46 (2.6) | 11 (4.1) | 2,539 (3.6) | |

| for kidney transplant | 0 | 21 (0.9) | 14 (0.8) | 5 (2.1) | 40 (0.1) | |

| missing | n/a | 447 (19.2) | 229 (13.2) | 48 (19.8) | 724 (1.0) | |

| TIME BETWEEN SERIAL TRANSPLANTS, n (%) | ||||||

| < 1 yrs | N/A | N/A | 177 (10.2) | 24 (9.9) | 201 (0.3) | |

| 1–5 yrs | N/A | N/A | 582 (33.5) | 89 (36.8) | 671 (1.0) | |

| > 5 yrs | N/A | N/A | 979 (56.3) | 129 (53.3) | 1,108 (1.6) | |

| DONOR TYPE, n (%) | ||||||

| deceased donor | 63,729 (96.5) | 2,319 (99.7) | 1,699 (97.8) | 238 (98.4) | 67,985 (96.7) | |

| living donor | 2,297 (3.5) | 8 (0.3) | 39 (2.2) | 4 (1.7) | 2,348 (3.3) | |

| SERUM CREATININE (mg/dL) | ||||||

| < 2.0 | 57,377 (86.9) | 306 (13.2) | 1,301 (74.9) | 71 (29.3) | 59,055 (84.0) | |

| ≥ 2.0 | 7,997 (12.1) | 2,003 (86.1) | 418 (24.1) | 167 (69.0) | 10,585 (15.0) | |

| missing | 652 (1.0) | 18 (0.8) | 19 (1.1) | 4 (1.7) | 693 (1.0) | |

| DONOR AGE | ||||||

| < 60 | 57,959 (87.8) | 2,194 (94.3) | 1,575 (90.6) | 223 (92.2) | 61,951 (88.1) | |

| ≥ 60 | 8,040 (12.2) | 133 (5.7) | 162 (9.3) | 19 (7.0) | 8,354 (11.9) | |

| missing | 27 (0.04) | 0 | 1 (0.06) | 0 | 28 (0.04) | |

| DONOR RACE | ||||||

| Caucasian | 49,452 (74.9) | 1,611 (69.2) | 1,347 (77.5) | 183 (75.6) | 52,593 (74.8) | |

| Black | 7,854 (11.9) | 302 (13.0) | 195 (11.2) | 31 (12.8) | 8,382 (11.9) | |

| Hispanic | 6,771 (10.3) | 325 (14.0) | 147 (8.5) | 21 (8.7) | 7,264 (10.3) | |

| Other | 1,949 (3.0) | 89 (3.8) | 49 (2.8) | 7 (2.9) | 2,094 (3.0) | |

| COLD ISCHEMIA TIME (CIT) | ||||||

| < 6 hrs | 13,946 (21.1) | 606 (26.0) | 248 (14.3) | 43 (17.8) | 14,843 (21.1) | |

| 6–12 hrs | 36,225 (54.9) | 1,267 (54.5) | 990 (57.0) | 144 (59.5) | 38,626 (54.9) | |

| > 12 hrs | 8,657 (13.1) | 190 (8.2) | 346 (19.9) | 21 (8.7) | 9,214 (13.1) | |

| missing | 7,198 (10.9) | 264 (11.4) | 154 (8.9) | 34 (14.1) | 7,650 (10.9) | |

| WARM ISCHEMIA TIME (WIT) | ||||||

| < 30 mins | 5,837 (8.8) | 288 (12.4) | 123 (7.1) | 28 (11.6) | 6,276 (8.9) | |

| 30–60 mins | 33,186 (50.3) | 1,060 (45.6) | 916 (52.7) | 114 (47.1) | 35,276 (50.2) | |

| > 60 mins | 10,734 (16.3) | 221 (9.5) | 447 (25.7) | 31 (12.8) | 11,433 (16.3) | |

| missing | 16,269 (24.6) | 758 (32.6) | 252 (14.5) | 69 (28.5) | 17,348 (24.7) | |

PSC includes total liver transplants secondary to Crohn’s disease [n=622 (0.9%)], ulcerative colitis [n=1,826 (2.6%)], no bowel disease [n=1,241 (1.8%)], and other [n=960 (1.4%)].

Donor Demographics

Donor age less than 60 years was commonly seen throughout all liver transplant groups, which accounted for 88.1% of total liver transplants. Caucasian was the commonest donor ethnicity of all the liver transplant groups, which accounted for 74.8% of total transplants. CIT between 6 and 12 hours and WIT between 30 and 60 minutes were of the majority in each transplant group accounting for 54.9% and 50.2% of all liver transplants, respectively.

Transplant Type

As shown in Figure 1, there was a steady increase in the number of SLK from 1988 with a distinct deviation between SLK and KALT after adoption of the MELD score in 2002. Accordingly, there was a 233% increase in the number of SLK, which coincided with a 74% decrease in KALT from 2001 to 2007.

Figure 1.

Recipient Mortality

After controlling for potential confounding demographic and clinical variables in the multivariate model, independent predictors of overall recipient mortality were identified and are listed in Table 2. Compared to Caucasians, African Americans had a 29% increased risk of mortality, whereas Hispanics had a 9% decreased risk of mortality. Longer time on waiting list was more protective with a decrease in mortality by 17% for those on the waiting list longer than 3 years compared to those on the list less than 1 year. Female gender was also protective with a decreased risk of mortality by 5%. The risk of mortality increased with age as recipients older than age 65 had an 86% increased risk of mortality compared to recipients’ ages 18 to 34. Transplant recipients with serum creatinine ≥2.0 mg/dL at time of transplant had a 41% increased risk of mortality than those with serum creatinine <2.0 mg/dL. HCV and DM status were also found to be independent predictors of recipient mortality. Specifically, compared to HCV-negative/DM-negative recipients, there was a 44%, 32%, and 72% increased risk of recipient mortality for HCV-positive/DM-negative, HCV-negative/DM-positive, and HCV-positive/ DM-positive recipients, respectively. Donor variables such as age greater than 60, Hispanic donor, CIT >6 hours, and WIT >30 minutes were also found to be independent predictors of overall recipient mortality.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for recipient mortality in all liver transplants.

| Recipient Mortality | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

| Sex (vs. male) |

|||

| Female | 0.95 | 0.92–0.97 | <0.0001 |

| Age (vs. 18–34 yrs) |

|||

| 35–49 yrs | 1.11 | 1.06–1.17 | <0.0001 |

| 50–64 yrs | 1.37 | 1.31–1.44 | <0.0001 |

| ≥65 yrs | 1.86 | 1.75–1.97 | <0.0001 |

| Race (vs. Caucasian) |

|||

| Black | 1.29 | 1.24–1.35 | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic | 0.91 | 0.88–0.95 | <0.0001 |

| HCV/DM status (vs. HCV-negative/DM-negative) |

|||

| HCV positive/DM positive | 1.72 | 1.63–1.82 | <0.0001 |

| HCV positive/DM negative | 1.44 | 1.39–1.50 | <0.0001 |

| HCV negative/DM positive | 1.32 | 1.25–1.39 | <0.0001 |

| Time on waiting list (vs. <1 yr) |

|||

| 1–3 yrs | 0.91 | 0.88–0.94 | <0.0001 |

| >3 yrs | 0.83 | 0.77–0.90 | <0.0001 |

| Donor type (vs. living donor) |

|||

| deceased | 1.03 | 0.95–1.12 | 0.431 |

| Transplant subgroups (vs. LTA) |

|||

| SLK | 0.92 | 0.86–0.99 | 0.024 |

| KALT <3 months | 2.32 | 1.74–3.10 | <0.0001 |

| KALT 3–6 months | 3.04 | 1.52–6.08 | 0.0017 |

| KALT 6–12 months | 0.85 | 0.47–1.54 | 0.589 |

| KALT >12 months | 1.40 | 1.28–1.52 | <0.0001 |

| LAKT | 1.43 | 1.20–1.72 | 0.0001 |

| Donor age (vs. <60 yrs) |

|||

| ≥60 yrs | 1.40 | 1.35–1.45 | <0.0001 |

| Donor Race (vs. Caucasian) |

|||

| Black | 1.04 | 1.00–1.08 | 0.0468 |

| Hispanic | 1.08 | 1.04–1.13 | 0.0001 |

| Other | 1.13 | 1.05–1.21 | 0.0008 |

| Serum creatinine at time of transplant (vs. <2.0 mg/dL) |

|||

| ≥2.0 mg/dL | 1.41 | 1.36–1.46 | <0.0001 |

| Cold ischemia time (CIT) (vs. <6 hrs) |

|||

| 6–12 hrs | 1.08 | 1.04–1.11 | <0.0001 |

| >12 hrs | 1.20 | 1.15–1.25 | <0.0001 |

| Warm ischemia time (WIT) (vs. <30 mins) |

|||

| 30–60 mins | 1.10 | 1.05–1.15 | <0.0001 |

| >60 mins | 1.25 | 1.18–1.31 | <0.0001 |

Although approaching statistical significance, there was no increased risk of overall recipient mortality in SLK compared to LTA (Hazard Ratio [HR]=0.92, p-value=0.024; Table 2). On the other hand, there was a 43% increased risk of recipient mortality in LAKT compared to LTA (HR=1.43, p-value=0.0001). Although there was no increased risk of recipient survival following KALT between 6 and 12 months compared to LTA, there were considerable increases in recipient mortality in all other KALT subgroups compared to LTA.

The unadjusted KM survival curve for overall recipient survival is shown in Figure 2. The survival curve for LTA is significantly higher compared to all other transplant subgroups (p<0.0001). The survival curve for SLK is significantly higher compared to both KALT (p<0.0001) and LAKT (p=0.003). There was no difference between KALT compared to LAKT (p=0.6409). Similar trends were present after adjusting for potential confounding demographic and clinical variables, except there was no statistically significant difference in overall recipient mortality between LTA and SLK (p=0.024).

Figure 2.

To further subdivide the relatively heterogenous KALT group, the group was separated based upon timing of kidney transplant in relation to preceding liver transplant. Specifically, KALT was divided into KALT <3 months (kidney transplant less than 3 months after liver transplant, n=72), KALT 3–6 months (n=12), KALT 6–12 months (n=30), and KALT >12 months (n=1,624). The unadjusted KM survival curves for overall recipient survival for these KALT subgroups compared to SLK is shown in Figure 3. Similar to Figure 2 where SLK recipient survival was significantly higher than overall KALT, SLK survival was significantly higher than each KALT subgroup except KALT 6–12 months (p=0.8419). There was no statistical difference in survival curves between the different KALT subgroups except for KALT <3 months compared to KALT >12 months (p=0.0029). Similar trends were present after adjusting for potential confounding variables.

Figure 3.

The overall recipient survival rates for each transplant group 1, 3, 5, and 10 years after transplant are shown in Table 3. LTA recipients had significantly higher overall survival rates throughout the 10-year post-transplant period compared to SLK, LAKT, and overall KALT (p≤0.005), except compared to LAKT at 10 years (p=0.0139). Specifically, LTA had 1-, 3-, 5- and 10-year survival rates of 84.4%, 75.4%, 68.4% and 51.4%, respectively. However, survival rates for LTA compared to the KALT subgroups showed that LTA was significantly higher only compared to KALT <3 months at 1-year post transplants (p<0.0001) and <3 and >12 months for 3, 5, and 10 years post transplant (p≤0.0002). Although significantly lower, SLK survival rates were similar to those of LTA with a 1-, 3-, 5-, and 10-year survival rate of 81.8%, 71.7%, 64.1%, and 46.5%, respectively. Similar to LTA, SLK survival rates were significantly higher than only KALT <3 months (1, 3, 5, and 10 years; p≤0.0003) and KALT >12 months (3, 5, and 10 years; p≤0.0028). On average, LAKT survival rates were approximately 10% worse than SLK (p<0.0001). KALT >12 months, which accounted for 93.4% of total KALT, had 1, 3, 5, and 10 year survival rates of 75.5%, 53.9%, 46.1%, and 30.5%, respectively, which is higher compared to the 1, 3, 5, and 10 year survival rates for KALT <3 months of 36.5% (p<0.0001), 31.3% (p=0.0078), 28.1% (p=0.0228), and 24.6% (p=0.3808), respectively. On the other hand, recipients of KALT <3 months, which accounted for 4.1% of total KALT recipients, had the lowest 1-, 3-, 5-, and 10-year recipient survival rates of 36.5%, 31.1%, 28.1%, and 24.6%, respectively.

Table 3.

Recipient survival rates for LTA, SLK, KALT (overall), and LAKT (main transplant groups) and KALT <3, 3–6, 6–12, and >12 months at 1, 3, 5, and 10 years after transplantation.

| Overall Recipient Survival | 1 year | 3 year | 5 year | 10 year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transplant groups | S (%) | 95% CI | S (%) | 95% CI | S (%) | 95% CI | S (%) | 95% CI |

| LTA | 84.4a | 84.1–84.7 | 75.4c | 75.1–75.8 | 68.4c | 68.0–68.8 | 51.4f | 50.9–51.9 |

| SLK | 81.8a | 80.1–83.3 | 71.7c | 69.8–73.6 | 64.1c | 61.8–66.3 | 46.5c | 43.0–49.8 |

| LAKT | 71.0b | 64.9–76.3 | 61.2b | 54.7–67.1 | 54.2b | 47.3–60.6 | 40.4g | 31.7–49.0 |

| KALT (overall) | 33.4s | 21.7–45.4 | 25.4s | 16.5–35.4 | 22.0s | 14.4–30.5 | 14.7s | 9.7–20.6 |

| KALT <3 months | 36.5d | 23.3-49.7 | 31.1d | 19.4–43.5 | 28.1e | 17.1–40.2 | 24.6i | 14.2–36.4 |

| KALT 3–6 months | 68.0n | 35.6–86.6 | 52.0n | 22.9–74.9 | 52.0n | 22.9–74.9 | 22.6n | 2.9–53.6 |

| KALT 6–12 months | 89.3k | 70.3–96.4 | 82.8l | 64.6–92.2 | 78.1l | 57.2–89.6 | 55.6m | 28.5–76.0 |

| KALT >12 months | 75.5m | 58.3–86.4 | 53.9h | 41.8–64.6 | 46.1i | 35.9–55.8 | 30.5j | 23.8–37.4 |

S survival estimator

CI confidence interval

significant compared to all other main transplant groups and KALT <3 months

significant compared to all other main transplant groups and KALT <3 and 6–12 months

significant compared to all other main transplant groups and KALT <3 and >12 months

significant compared to all other main transplant groups and KALT 6–12 and >12 months

significant compared to all other main transplant groups and KALT 6–12 months

significant compared to SLK, KALT (overall) and KALT <3 and >12 months

significant compared to SLK and KALT (overall)

significant compared to LTA, SLK, KALT <3 and 6–12 months

significant compared to LTA, SLK, and KALT 6–12 months

significant compared to LTA and SLK

significant compared to LAKT and KALT <3 months

significant compared to LAKT, KALT <3 and >12 months

significant compared to only KALT <3 months

not significant [p≥0.01] compared to any other transplant group

significant [p<0.01] compared to all other transplant groups

Graft Loss

The HRs for graft loss are shown in Table 4, which are similar to those for recipient mortality (Table 2) relative to recipient variables, such as gender, ethnicity, pre-transplant serum creatinine, time on waitlist, and HCV/DM status as well as donor variables, such as age, CIT and WIT. Unlike recipient mortality, recipient age was not predictive of increased graft loss until the age of 65. Although donor type was not associated with an increased risk of recipient mortality, deceased donor was associated with a 10% reduction in the risk of graft loss compared to living donor. As compared to Caucasian donors, African American donors inferred a 9% increased risk of graft loss, which was absent in the multivariate analysis of recipient mortality. Similar patterns of increased risk of graft loss were also seen in LAKT and KALT subgroups compared to LTA. Similar to recipient mortality, when compared to LTA, KALT >12 months increased the risk of graft loss by 39%. Furthermore, LAKT assumed a 34% increased risk of graft loss when compared to LTA. However, unlike recipient mortality, SLK had a decreased risk of graft loss by 15% compared to LTA (HR=0.85, p<0.0001). As was the case in recipient mortality, donor age greater than 60 years, Hispanic donor, serum creatinine ≥2 mg/dL, CIT >12 hours, and WIT >60 minutes were also found to be independent risk factors for graft loss.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for graft loss in all liver transplants.

| Graft Loss | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

| Sex (vs. male) |

|||

| Female | 0.96 | 0.93–0.98 | 0.0002 |

| Age (vs. 18–34 yrs) |

|||

| 35–49 yrs | 0.95 | 0.91–0.99 | 0.0278 |

| 50–64 yrs | 1.06 | 1.01–1.11 | 0.0159 |

| ≥65 yrs | 1.32 | 1.25–1.39 | <0.0001 |

| Race (vs. Caucasian) |

|||

| Black | 1.28 | 1.23–1.33 | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic | 0.92 | 0.88–0.95 | <0.0001 |

| HCV/DM status (vs. HCV-negative/DM-negative) |

|||

| HCV positive/DM positive | 1.57 | 1.49–1.66 | <0.0001 |

| HCV positive/DM negative | 1.36 | 1.32–1.41 | <0.0001 |

| HCV negative/DM positive | 1.24 | 1.18–1.31 | <0.0001 |

| Time on waiting list (vs. <1 yr) |

|||

| 1–3 yrs | 0.91 | 0.88–0.94 | <0.0001 |

| >3 yrs | 0.84 | 0.78–0.90 | <0.0001 |

| Donor type (vs. living donor) |

|||

| deceased | 0.90 | 0.83–0.97 | 0.004 |

| Transplant subgroups (vs. LTA) |

|||

| SLK | 0.85 | 0.79–0.92 | <0.0001 |

| KALT <3 months | 1.60 | 0.91–2.81 | 0.1065 |

| KALT 3–6 months | 2.97 | 0.75–11.77 | 0.1214 |

| KALT 6–12 months | 0.81 | 0.37–1.81 | 0.6131 |

| KALT >12 months | 1.39 | 1.25–1.54 | <0.0001 |

| LAKT | 1.34 | 1.12–1.61 | 0.0012 |

| Donor age (vs. <60 yrs) |

|||

| ≥60 yrs | 1.51 | 1.46–1.56 | <0.0001 |

| Donor Race (vs. Caucasian) |

|||

| Black | 1.09 | 1.05–1.13 | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic | 1.07 | 1.03–1.11 | 0.0010 |

| Other | 1.12 | 1.04–1.20 | 0.0017 |

| Serum creatinine at time of transplant (vs. <2.0 mg/dL) |

|||

| ≥2.0 mg/dL | 1.35 | 1.31–1.39 | <0.0001 |

| Cold ischemia time (CIT) (vs. <6 hrs) |

|||

| 6–12 hrs | 1.11 | 1.07–1.14 | <0.0001 |

| >12 hrs | 1.28 | 1.23–1.33 | <0.0001 |

| Warm ischemia time (WIT) (vs. <30 mins) |

|||

| 30–60 mins | 1.09 | 1.04–1.14 | 0.0002 |

| >60 mins | 1.24 | 1.18–1.30 | <0.0001 |

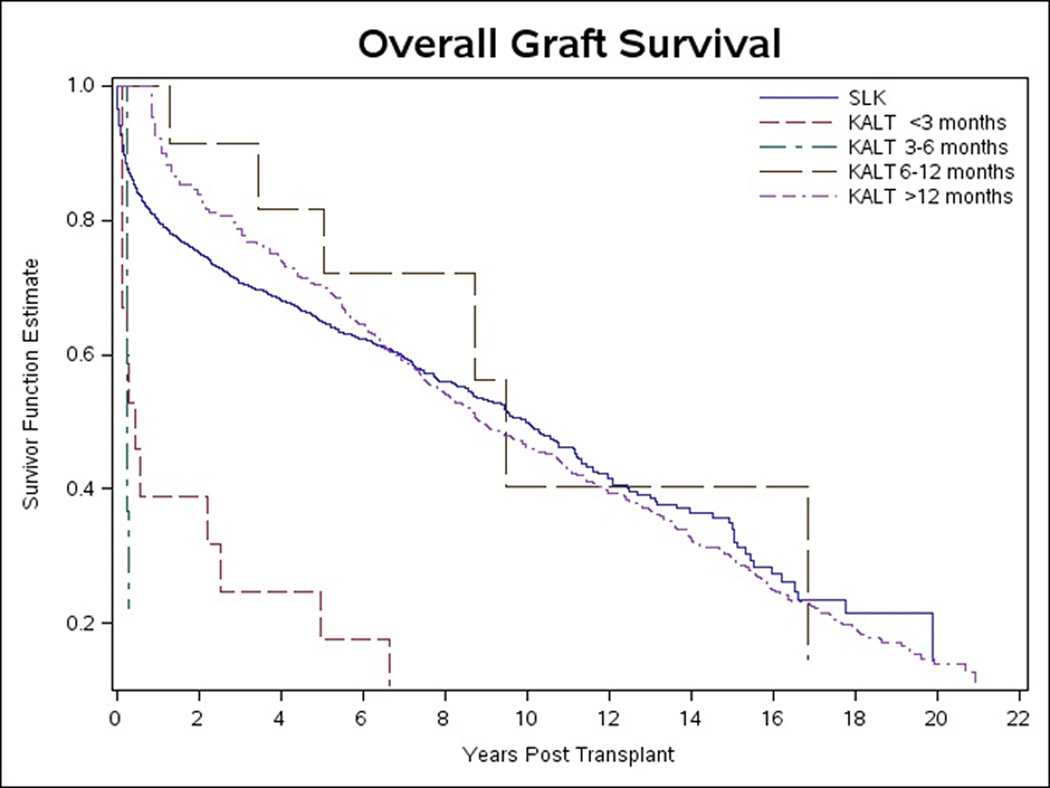

The unadjusted KM survival curve for overall graft survival is shown in Figure 4. Similar to overall recipient survival (Figure 2), the overall graft survival curve for LTA and SLK are each significantly higher compared to both KALT and LAKT (p<0.0001). Unlike overall recipient survival, the overall graft survival for LAKT is significantly higher than KALT (p<0.0001). Although there is no difference between the survival curve for LTA and SLK in the unadjusted model (p=0.2747), after adjusting for potential confounding demographic and clinical variables, overall graft survival was significantly higher in the SLK group compared to the LTA group (p<0.0001)

Figure 4.

The unadjusted KM survival curve for overall graft survival of the KALT subgroups compared to SLK is shown in Figure 5. SLK graft survival curve was significantly higher compared to KALT <3 months (p<0.0001) and KALT >12 months (p<0.0001). Similar trends were present after adjusting for potential confounding variables, except SLK was significantly higher than only KALT >12 months (p<0.0001).

Figure 5.

The graft survival rates for each transplant group 1, 3, 5, and 10 years after transplant are shown in Table 5. Although the graft survival rates follow a similar trend compared to recipient survival, there was no difference between LTA and SLK (1-yr p=0.5091, 3-yr p=0.3345, 5-yr p=0.7144, and 10-yr p=0.7561). Similar to recipient survival, graft survival in SLK was significantly higher compared to both overall KALT and LAKT for each of the same time periods. KALT >12 months (the largest KALT subgroup) was significantly higher than LTA, SLK, and LAKT only at 3-years post transplant (p<0.0001). Otherwise, KALT >12 months was significantly higher than only LAKT, KALT <3 and 3–6 months at 1 year (p≤0.0061), LAKT and KALT <3 months at 5 years (p≤0.009), and KALT <3 and 6–12 months at 10 years (p=0.0042). Although KALT 3–6 months had the lowest graft survival rates, these were rarely significant. KALT <3 months, on the other hand, had the lowest significant graft survival rates. Specifically, KALT <3 had 1-, 3-, 5-, and 10-year graft survival rates of 38.8%, 24.8%, 17.8%, and 10.8%, respectively.

Table 5.

Graft survival rates for LTA, SLK, KALT (overall), and LAKT (main transplant groups) and KALT <3, 3–6, 6–12, and >12 months at 1, 3, 5, and 10 years after transplantation.

| Overall Graft Survival | 1 year | 3 year | 5 year | 10 year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transplant groups | S (%) | 95% CI | S (%) | 95% CI | S (%) | 95% CI | S (%) | 95% CI |

| LTA | 80.4a | 80.1–80.7 | 71.7a | 71.4–72.1 | 65.4a | 65.0–65.8 | 50.5b | 50.0–51.0 |

| SLK | 79.9a | 78.2–81.5 | 70.8d | 68.8–72.6 | 65.0a | 62.7–67.2 | 50.0b | 46.6–53.3 |

| LAKT | 68.4i | 62.1–73.9 | 58.5g | 51.9–64.5 | 53.3h | 46.5–59.7 | 38.0b | 50.0–51.0 |

| KALT (overall) | 36.3e | 12.4–61.2 | 31.0e | 11.1–53.6 | 27.6e | 10.2–48.4 | 18.2e | 7.2–33.1 |

| KALT <3 months | 38.8i | 11.7–65.9 | 24.8l | 5.8–50.5 | 17.8l | 3.2–42.0 | 10.8l | 1.2–32.8 |

| KALT 3–6 months | 22.3p | 0.2–70.6 | 22.3o | 0.2–70.6 | 22.3q | 0.2–70.6 | 22.3q | 0.2–70.6 |

| KALT 6–12 months | 100.0 | n/a | 91.3s | 52.5–98.7 | 81.7m | 44.3–95.1 | 81.7k | 44.3–95.1 |

| KALT >12 months | 92.2s | 71.8–98.0 | 78.6j | 76.9–80.3 | 70.1r | 57.9–79.4 | 46.3n | 38.4–53.8 |

S survival estimator

CI confidence interval

significant compared to LAKT, KALT (overall), and KALT <3 months

significant compared to LAKT, KALT (overall), KALT <3 and 3–6 months

significant compared to LAKT, KALT (overall), KALT <3, 6–12, and >12 months

significant compared to LAKT, KALT (overall), KALT <3, and >12 months

significant compared to LTA and SLK

significant compared to LTA, SLK, KALT <3 and 6–12 months

significant compared to LTA, SLK, KALT <3, 6–12, and >12 months

significant compared to LTA, SLK, KALT 6–12 and >12 months

significant compared to LTA, SLK, and KALT >12 months

significant compared to all other main transplant groups and KALT <3 months

significant compared to all other main transplant groups, KALT <3 and >12 months

significant compared to all other main transplant groups, KALT 6–12 and >12 months

significant only compared to KALT <3 months

significant only compared to KALT <3 and 6–12 months

significant only compared to KALT 6–12 months

significant only compared to KALT >12 months

not significant (p≥0.01) compared to any other transplant group

significant compared to LAKT and KALT <3 months

significant compared to LAKT, KALT <3 and 3–6 months

The cumulative incidence probabilities for death with the original graft prior to liver retransplantation and liver retransplantation are listed in Table 6 and displayed as Figures 6 and 7, respectively. There was a slightly higher probability of death prior to retransplantion in SLK compared to LTA recipients (p<0.0001). On the other hand, LTA had a significantly higher probability for recipient death prior to retransplantation compared to overall KALT (p<0.0001). LAKT recipients had higher probabilities for recipient death prior to retransplantation than both LTA (p<0.0001) and SLK (p=0.0021). Although the incidence of recipient death for SLK was only slightly higher than LTA, the incidence of liver retransplantation was nearly 50% higher in LTA (p<0.0001). The incidence of liver retransplantation in KALT recipients accounted for approximately 50% of graft loss, which was statistically higher compared to only SLK (p=0.0066).

Table 6.

Cumulative incidence probabilities for death and liver retransplantation.

| LTA | SLK | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | death (%) | retransplant (%) | graft survival (%) | death (%) | retransplant (%) | graft survival (%) |

| 3 months | 10 | 6 | 84 | 9 | 3 | 88 |

| 6 months | 10 | 6 | 84 | 13 | 3 | 84 |

| 1 year | 13 | 7 | 80 | 16 | 4 | 80 |

| 2 years | 18 | 7 | 75 | 22 | 4 | 74 |

| 5 years | 27 | 8 | 65 | 31 | 4 | 65 |

| 10 years | 41 | 9 | 50 | 45 | 5 | 50 |

| 15 years | 57 | 12 | 31 | 64 | 5 | 31 |

| 20 years | 67 | 14 | 19 | 82 | 6 | 12 |

| KALT | LAKT | |||||

| Time | death (%) | retransplant (%) | graft survival (%) | death (%) | retransplant (%) | graft survival (%) |

| 3 months | 7 | 36 | 57 | 19 | 3 | 78 |

| 6 months | 16 | 47 | 37 | 23 | 4 | 73 |

| 1 year | 16 | 48 | 36 | 27 | 5 | 68 |

| 2 years | 20 | 49 | 31 | 32 | 5 | 63 |

| 5 years | 22 | 50 | 28 | 42 | 5 | 53 |

| 10 years | 32 | 50 | 18 | 55 | 7 | 38 |

| 15 years | 38 | 51 | 11 | 64 | 10 | 26 |

| 20 years | 44 | 51 | 5 | 64 | 10 | 26 |

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

DISCUSSION

We report here the long-term follow-up of 70,333 liver transplant recipients; to our knowledge the largest retrospective review of recipient and graft survival of LTA, SLK and serial liver-kidney transplants.

Simultaneous Liver-Kidney Transplantation

The 1- and 5-year recipient and graft survival rates demonstrated in our study are similar to those presented in previous studies (see table 7) including the largest previous study of 1,136 SLK recipients by Simpson et al.12 Although the recipient survival rates for SLK at 1, 3, 5, and 10 years post-transplant in our study were on average 4% worse than LTA, there was no increased risk of overall recipient mortality in SLK compared to LTA in our multivariate analysis model. Although there was no difference in graft survival rates between LTA and SLK at 1, 3, 5, and 10 years post transplant, the risk of graft loss was significantly decreased in SLK recipients compared to LTA recipients.

Table 7.

Previously reported survival outcomes for SLK.

| Author | Number of patients (n) |

Recipient Survival (%) |

Liver Graft Survival (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLK | 1-year | 5-year | 1-year | 5-year | |

| Jeyarajah, et al 199717 | 29 | 78.6 (2-yr) | 48.1 | 62.7 (2-yr) | 41.2 |

| Becker, et al 200315 | 38 | 73.7 | 64.1 | 68c | 56c |

| Creput, et al 200310 | 45 | 85 | 82 (2-yr) | ||

| Fong, et al 200311 | 800 | 74c | 64 | ||

| Simpson, et al 200612 | 1,136 | 80c | 65c | ||

| Ruiz, et al 200618 | 99 | 76 | 70 | 70 | 65 |

| Locke, et al 200814 | 1,032 | 82 | 79.6 | ||

| Schmitt, et al 200919 | 959 | 79.4a, 81.0b | 69 a, c 65 b, c (3-yr) | ||

| Van Wagner, et al 200920 | 38d | 73.7 | 68.1 | 73.7 | 53.0 |

| Martin, et al (current study) | 2,327 | 81.8 | 64.1 | 79.9 | 65.0 |

HD cohort,

non-HD cohort,

estimated from corresponding survival curve,

all patients were HCV-positive

Many previous studies have also shown a reduced incidence of renal allograft rejection following SLK compared to KALT.10–12 In the largest such study by Simpson et al, it was hypothesized that the liver allograft provides a form of renal graft immunoprotection via immunogenetic identity following SLK, which is absent in KALT.12 In the same study, there was no difference in recipient or renal graft survival between SLK and KALT. Although the recipient survival rates for SLK in their study are closely matched to those calculated in our study, we found that survival following SLK is significantly better than KALT.

Although prior studies have evaluated kidney graft survival in SLK, few have reported liver graft survival. Of those who reviewed kidney graft survival, the main cause of mortality and subsequent graft failure was severe infectious complications.10 Decreased survival in SLK versus LTA may be due to the inherent severity of illness in recipients with ESLD and ESRD as evident by higher MELD scores at the time of transplantation and the associated subsequent risks and complications immediately following transplantation.

Prior to the first SLK performed in 1984 by Margreiter et al9, significant renal impairment was considered a contraindication for OLTX. Due to allocation of organs based on MELD score, which is heavily impacted by renal disease, liver transplant candidates are now given priority for renal dysfunction. The rationale for SLK is easily justified in patients with ESLD in the setting of ESRD requiring chronic renal replacement therapy (RRT). However, the matter is more complicated in patients with ESLD who develop acute renal failure when the duration or potential reversibility of the renal failure is uncertain as is often the case in hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) type II. HRS is generally not considered an indication for SLK due to the well-documented reversibility of the renal failure after OLTX.21,22 It has also been shown that kidneys transplanted from donors with HRS results in good renal function.23 However, there is currently no consensus as to the duration of HRS or RRT after which renal dysfunction is not reversible. The lack of this consensus sets the stage for the debate between proceeding with upfront SLK versus LTA with the potential need for sequential renal transplant.

The advantages of SLK appear to outweigh the disadvantages. As previously mentioned, one main advantage of SLK is the enhanced outcomes compared to KALT and LAKT likely due to the apparent immunoprotection afforded to the kidney from the transplanted liver. Secondly, a well-functioning kidney allows optimal dosing of necessary immunosuppressants. Lastly, several studies have confirmed the presence of immune-complex mediated glomerulonephropathy (GN) in HCV-positive patients undergoing OLTX even in the absence of clinical signs or symptoms.24–27 In HCV recipients in particular, the underlying renal disease is surely exacerbated following OLTX, which would otherwise be preserved in SLK.

The need for better standardization of organ allocation in SLK candidates is perhaps best illustrated by the large disparity in the number of SLK performed throughout US transplant centers with SLK accounting for just over 6% of total OLTX in 2007 according to UNOS/OPTN data compared to a rate as high as 45% in some transplant centers.28 Furthermore, in a separate review of UNOS/OPTN data, a renal diagnosis was missing or “not specified” in nearly 40% of SLK recipients.29 Also, in a study of 1,032 SLK recipients between 2002 and 2006, only 318 (30.8%) were on chronic hemodialysis (HD),14 suggesting that nearly 70% of the kidneys given to SLK recipients were placed too early. These examples alone are clear evidence that allocation of renal allografts in SLK candidates requires closer monitoring. Lack of standardized criteria for allocation of renal grafts to SLK candidates has the potential to adversely impact those awaiting kidney transplants in the MELD era. It follows that efforts should be made to optimize both organ utilization and outcomes in liver candidates with impaired renal function.

Two national, multidisciplinary consensus conferences were recently held to review current data and recommend to UNOS a standard listing criteria for SLK.28,30 These meetings were instrumental in the recent UNOS Policy proposal 3.5.10 (http://unos.org/PublicComment/pubcommentPropSub_237.pdf), which set forth minimum criteria for candidates listed for SLK. In brief, the first part of the proposal (3.5.10.1), recommends SLK listing of liver candidates based on CKD stage 4 or 5, acute renal failure (ARF) with GFR <25 mL/min for 6 consecutive weeks (regardless of need for RRT), and metabolic diseases, namely hyperoxaluria. The second part of the proposal (3.5.10.2) was established to clarify listing requirements for sequential kidney after liver transplantation, which is recommended for LTA recipients who remain HD-dependent for 3 months after OLTX.

Sequential Liver-Kidney Transplantation

The management of OLTX recipients who develop post-OLTX ESRD often includes KALT. Unfortunately, only a few relatively small studies have reviewed survival outcomes of serial liver-kidney transplantation with numbers ranging from 9 to 352 recipients (Table 8), the largest of which reported a reported 1- and 5-year recipient survival following KALT of 91% and 64%, respectively.12 This is in contrast to the current study which reports a 1- and 5-year recipient survival following KALT of 33.4% and 22.0%, respectively, which is considerably lower than previously reported data. However, we have included a much larger number of patients (1,738 KALT and 242 LAKT) and thus, our data may represent a more accurate picture of serial liver-kidney transplantation outcomes.

Table 8.

Previously reported survival outcomes for serial liver-kidney transplantations.

| Author | Number of patients (n) |

Patient Survival (%) |

Liver Graft Survival (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KALT | LAKT | 1-year | 5-year | 1-year | 5-year | |

| Molmenti, et al 200142 | 17 | 88 | 71 (3-year) | 88 | 61 (3-year) | |

| Gonwa, et al 20013 | 16 | 95d | 62 | |||

| Becker, et al 200315 | 5 | 4 | 80a, 50b | 80a, 25b (4-year) | ||

| Simpson, et al 200612 | 352 | 91c | 64c | |||

| Martin, et al (current study) | 1,738 | 242 | 33.4a, 71.0b | 22.0a, 54.2b | 36.3a, 68.4b | 27.6a, 53.3b |

KALT,

LAKT,

estimated from corresponding survival curve,

all patients were HCV-positive

Varying degrees of renal insufficiency are common both before and after liver transplantation. According to a well-cited retrospective review of the UNOS database by Ojo et al in 2003, 27% of liver transplant recipients had abnormal renal function (GFR<60 mL/min) at the time of transplantation with 2.2% requiring HD.32 A more recent review by Eason et al in 2008 reported that 8.2% of all OLTX patients required HD at time of transplantation.28 Furthermore, studies have shown that 22% of OLTX recipients develop CRF within 5 years of transplantation,33 of which 2% to 10% of cases progress to ESRD by 10 years after transplantation.3 Of the OLTX recipients who develop ESRD, the 6-year survival after onset of ESRD has been reported only as high as 27% for those maintained on HD compared to 71.4% for those who subsequently underwent KALT.3 In a similar study by Paramesh et al, of 186 OLTX recipients who developed ARF requiring HD, 43 recipients (23%) developed ESRD after a mean of 5.6 years.34 Of these 43 recipients, 8 (18.6%) underwent subsequent KALT with a 10-year recipient survival of 71% compared to 21% for those who developed ESRD and maintained on HD. This is in clear contrast compared to the 14.7% 10-year recipient survival for KALT observed in our study.

We identified multiple demographic and clinical characteristics that negatively impact both recipient and graft survival, namely recipient age, ethnicity, HCV/DM status, and pretransplant serum creatinine as well as donor age, ethnicity, WIT, and CIT. An increased risk of recipient mortality was seen in recipients greater than 65 years of age. Although recipient age is not considered an absolute contraindication for OLTX, there are conflicting outcome studies in the current literature regarding the impact of recipient age on liver transplantation. One such study by Herrero et al concluded that recipients older than 60 years had a significantly lower survival compared to matched controls younger than 60 years.35 This is in contrast to much of the recent literature that fails to demonstrate an increased risk of recipient mortality or graft failure in elderly recipients undergoing OLTX,36–38 except in cases of “high risk” elderly patients with poor hepatic synthetic function, elevated bilirubin, or pretransplant hospital admission, who had significantly lower survival rates than “sicker” younger patients or “less-ill” older patients.38

Donor age, much like recipient age, has led to mixed results regarding its impact on recipient and graft survival.39–42 Unfortunately, most of these studies were retrospective chart reviews with relatively small sample sizes. Interestingly, one prospective study, which did not analyze recipient or graft survival, observed an increased number of hospitalizations and longer length of initial stay in recipients 60 years or older compared to recipients less than 60 years.43

Our study also shows that both black recipients and donors infer an increased risk of recipient and graft mortality. This is in contrast to a recent study by Asrani et al that demonstrated donor race, namely African American and Asian/Pacific Islander, was not associated with graft survival after OLTX.44 Although our study did not assess donor-recipient race mismatch, a significant interaction between donor and recipient race was noted on a recent study by Layden et al.45 Specifically, black recipients with Caucasian donors had a 66% higher risk of recipient mortality compared to Caucasian recipients with Caucasian donors. However, neither the survival of Caucasian recipients with black donors nor black recipients with black donors was significantly different compared to Caucasian recipients with Caucasian donors.

Similar to prior studies, our results demonstrate a strong negative impact of both HCV and DM on recipient and graft survival.46–51 Our results also demonstrate a profound negative impact of serum creatinine on both recipient and graft survival that is consistent with previously reported data.30,52,53 Lastly, our findings regarding the impact of WIT and CIT on recipient and graft survival are comparable to previously published data. Specifically, WIT more than 45 minutes and CIT more than 12 hours were associated with a significant increase in graft dysfunction.54 Furthermore, a recent large meta-analysis demonstrated significantly worse patient and graft survival associated with CIT more than 10 and 12.5 hours, respectively.55

LIMITATIONS

Our study suffers from the limitations inherent in a retrospective analysis of the UNOS database, namely the inability to validate the data provided as well as to control the immunosuppressive therapies and all the non-documented other potential interventions used. In an effort to overcome these limitations, a p-value of <0.01 was considered statistically significant to allow for a more strict assessment of statistical significance when using a large national database. Based on the available UNOS data, we were able to only identify the presence or absence of HCV and DM and not the length of either disease, their severity or their respective overall diabetic control, namely glycosylated hemoglobin or insulin versus dietary control. Furthermore, HCV and DM status were not recorded by UNOS until April 1, 1994, some 6 years into our study and in part explains the relatively large number of missing values in Table 1. In addition, we stratified the results based on the level of renal impairment using only serum creatinine levels and not the need for or duration of HD. Despite our intentions to include HD in our analysis, too many missing data prevented an accurate analysis of the impact of HD on recipient and graft survival. Similarly, our study does not make the distinction between preand post-MELD era outcomes.

There is also discrepancy in the number of SLK defined in the UNOS database compared to the number of SLK defined in our study. Although a large majority of the patients listed by UNOS as having SLK received a liver and kidney on the same day, 255 patients received the organs 1 day apart while 5 patients received the organs 2 days apart. No liver or kidney transplants were performed after 2 days from the initial date of transplantation if they were listed by UNOS as undergoing SLK. Similarly, of those not listed by UNOS as undergoing SLK, 204 patients received a kidney 1 day after a liver and 5 patients received a kidney 2 days after a liver. These 209 patients were added to the SLK group rather than the KALT group. In addition, of those not listed as undergoing SLK, 52 patients received a liver 1 day after a kidney and 1 patient received a liver 2 days after a kidney. These 53 patients were also added to the SLK group rather than the LAKT group. For these reasons, we defined SLK as any combination of liver-kidney transplantation occurring 2 days or less from the original transplant.

In reality, the true prevalence of renal insufficiency in patients with ESLD is unknown. Given that most liver transplant candidates have decreased creatinine production, poor nutritional status, low muscle mass, weight loss, and edema, the use of serum creatinine alone results in an overestimation of GFR.56 Although the 6-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study equation was found to be the most accurate equation estimating GFR (compared to the Cockcroft-Gault and Nankivell formulas), all equations consistently overestimated kidney function in patients with a GFR <40mL/min as measured by I125 iothalamate.57 In addition, although GFR measurements are the current gold standard, they are both expensive and time consuming, which is why serum creatinine continues to be used by most studies examining kidney function. In fact, the diagnostic criteria for HRS according to the International Ascites Club include a serum creatinine of >1.5mg/dL.58 Therefore, the use of serum creatinine is an inherent limitation in most studies. If cost continues to limit the use of GFR measurements, then more studies are needed to evaluate the potential role for alternatives to serum creatinine, such as cystatin C. Cystatin C, which is a protein that is produced at a constant rate and is freely filtered and neither secreted nor reabsorbed, has been shown to be more accurate than serum creatinine in estimating renal function in patients with advanced liver disease as serum levels are independent of gender, muscle mass, and age.59

CONCLUSION

This is the largest retrospective review of recipient and graft survival of LTA, SLK and serial liver-kidney transplants. We provide a succinct review and compelling evidence to support the use of SLK as an effective and appropriate therapy in patients with ESLD with proven irreversible or chronic ESRD. Although the recent increase in SLK performed each year effectively decreases the number of potential donor kidneys available to patients with ESRD awaiting kidney transplantation, SLK in patients with ESLD and ESRD is justified due to lower risk of graft loss in SLK compared to LTA as well as superior recipient and graft survival compared to serial liver-kidney transplantation. With the apparent and perhaps inevitable trend of increasing SLK, prospective outcome studies are needed to further optimize organ allocation in liver transplant candidates with renal insufficiency. Efforts need to be routine in identifying liver transplant candidates with irreversible renal insufficiency that would best benefit from SLK.

Acknowledgements

The authors formally thank Katarina Linden and Denise Tripp for their assistance in acquiring the necessary data from UNOS/OPTN for the completion of this study. Statistical analysis was supported by grant 1UL1RR031973 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program of the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) in association with the National Institute of Health (NIH).

Abbreviations

- ARF

acute renal failure

- CI

confidence interval

- CIT

cold ischemia time

- CNIs

calcineurin inhibitors

- CRF

chronic renal failure

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- ESLD

end stage liver disease

- ESRD

end stage renal disease

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- GN

glomerulonephropathy

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HD

hemodialysis

- HR

hazard ratio

- HRS

hepatorenal syndrome

- KALT

kidney after liver transplantation

- KM

Kaplan Meier

- LAKT

liver after kidney transplantation

- LTA

liver transplant alone

- MELD

model for end-stage liver disease

- MDRD

Modification of Diet in Renal Disease

- MPGN

membranoproliferative glomerulonephropathy

- OLTX

orthotopic liver transplantation

- PBC

primary biliary cirrhosis

- PSC

primary sclerosing cholangitis

- PTDM

post-transplant diabetes mellitus

- RRT

renal replacement therapy

- SLK

simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation

- UNOS/OPTN

United Network for Organ Sharing/Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- WIT

warm ischemia time

REFERENCES

- 1.Jain A, Reyes J, Kashyap R, et al. Long-term survival after liver transplantation in 4000 consecutive patients at a single center. Ann Surg. 2000 Oct;232(4):490–500. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200010000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Multicenter FK-506 Liver Study Group. A comparison of tacrolimus (FK 506) and cyclosporine for immunosuppression in liver transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1994 Oct 27;331(17):1110–1115. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410273311702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonwa TA, Mai ML, Melton LB, et al. End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLTX) using calcineurin-based immunotherapy. Transplantation. 2001 Dec 27;72(12):1934–1939. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200112270-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher NC, Nightingale PG, Gunson BK, et al. Chronic renal failure after liver transplantation: A retrospective analysis. Transplantation. 1998 Jul 15;66(1):59–66. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199807150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klintmalm GB, Gonwa TA. Nephrotoxocity associated with cyclosporine and FK506. Liver Transpl Surg. 1995 Sep;1(5 Suppl 1):11–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jindal RM, Popescu I. Renal dysfunction associated with liver transplantation. Postgrad Med. 1995;71:513–524. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.71.839.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis CL, Gonwa TA, Wilkinson AH. Indentification of patients best suited for combined liver-kidney transplantation: Part II. Liver Transpl. 2002 Mar;8(3):193–211. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.32504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chava SP, Singh B, Zaman MB, et al. Current indications for combined liver and kidney transplantation in adults. Transplant Rev (Orlando) 2009 Apr;23(2):111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Margreiter R, Kramer R, Huber C, et al. Combined liver and kidney transplantation. Lancet. 1984 May 12;1(8385):1077–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91486-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creput C, Durrbach A, Samuel D, et al. Incidence of renal and liver rejection and patient survival rate following combined liver and kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2003 Mar;3(3):348–356. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fong TL, Bunnapradist S, Jordan SC, et al. Analysis of the United Network for Organ Sharing database comparing renal allografts and patient survival in combined liver-kidney transplantation with the contralateral allografts in kidney alone or kidney-pancreas transplantation. Transplantation. 2003 Jul 27;76(2):348–353. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000071204.03720.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simpson N, Cho YW, Cicciarelli JC, et al. Comparison of renal allograft outcomes in combined liver-kidney tranplantation versus subsequent kidney transplantation in liver transplant recipients: Analysis of UNOS database. Transplantation. 2006 Nov 27;82(10):1298–1303. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000241104.58576.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogers J, Bueno J, Shapiro R, et al. Results of simultaneous and sequential pediatric liver and kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2001 Nov 27;72(10):1666–1670. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200111270-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Locke JE, Warren DS, Singer AL, et al. Declining outcomes in simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation in the MELD era: Ineffective usage of renal allografts. Transplantation. 2008 Apr 15;85(7):935–942. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318168476d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Becker T, Nyibata M, Lueck R, et al. Results of combined and sequential liver-kidney transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2003 Oct;9(10):1067–1078. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katznelson S, Cecka JM. The liver neither protects the kidney from rejection nor improves kidney graft survival after combined liver and kidney transplantation from the same donor. Transplantation. 1996 May 15;61(9):1403–1405. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199605150-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeyarajah DR, Gonwa TA, McBride M, et al. Hepatorenal syndrome: Combined liver kidney transplants versus isolated liver transplant. Transplantation. 1997 Dec 27;64(12):1760–1765. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199712270-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruiz R, Hunitake H, Wilkinson AH, et al. Long-term analysis of combined liver and kidney transplantation at a single center. Arch Surg. 2006 Aug;141(8):735–741. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.8.735. discussion 741-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmitt TM, Kumer SC, Al-Osaimi A, et al. Combined liver-kidney and liver transplantation in patients with renal failure outcomes in the MELD era. Transpl Int. 2009 Sep;22(9):876–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Wagner LB, Baker T, Ahya SN, et al. Outcomes of patients with hepatitis C undergoing simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation. J Hepatol. 2009 Nov;51(5):874–880. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wood RP, Ellis D, Starzel TE. The reversal of the hepatorenal syndrome in four pediatric patients following successful orthotopic liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 1987 Apr;205(4):415–419. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198704000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwatsuki S, Popovtzer MM, Goldstein G, et al. Recovery from “hepatorenal syndrome” after orthotopic liver transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1973 Nov 29;289(22):1155–1159. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197311292892201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koppel MH, Coburn JW, Mims MM, et al. Transplantation of cadaveric kidneys from patients with hepatorenal syndrome: evidence for the functional nature of renal failure in advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med. 1969 Jun 19;280(25):1367–1371. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196906192802501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGuire BM, Julian BA, Bynon S, et al. Brief Communication: Glomerulonephritis in patients with hepatitis C cirrhosis undergoing liver transplantation. Ann Intern Med. 2006 May 16;144(10):735–741. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morales JM, Pascual-Capdevila J, Campistol JM, et al. Membranous glomerulonephritis associated with hepatitis C virus infection in renal transplant patients. Transplantation. 1997;63(11):1634–1639. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199706150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cosio FG, Roche Z, Agarwal A, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C in patients with idiopathic glomerulopathies in native and transplant kidneys. Am J Kid Dis. 1996;28(5):752–758. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(96)90260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim JY, Akalin E, Dikman S, et al. The variable pathology of kidney disease after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2010 Jan 27;89(2):215–221. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181c353e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eason JD, Gonwa TA, Davis CL, et al. Proceedings of consensus conference on simultaneous liver kidney transplantation (SLK) Am J Transplant. 2008 Nov;8(11):2243–2251. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonwa TA, McBride MA, Anderson K, et al. Continued influence of preoperative renal function on outcome of orthotopic liver transplant (OLTX) in the US: Where will MELD lead us? Am J Transpl. 2006;6:2651–2659. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis CL, Feng S, Sung R, et al. Simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation: Evaluation to decision making. Am J Transplant. 2007 Jul;7(7):1702–1709. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molmenti EP, Jain AB, Shapiro R, et al. Kidney transplantation for end-stage renal failure in liver transplant recipients with hepatitis C viral infection. Transplantation. 2001 Jan 27;71(2):267–271. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200101270-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ojo AO, Held PJ, Port FK, et al. Chronic renal failure after transplantation of a nonrenal organ. N Engl J Med. 2003 Sep 4;349(10):931–940. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharma P, Welch K, Eidstadt R, et al. Renal outcomes after liver transplantation in the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease era. Liver Transpl. 2009 Sep;15(9):1142–1148. doi: 10.1002/lt.21821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paramesh AS, Roayaie S, Doan Y, et al. Post-liver transplant acute renal failure: factors predicting development of end-stage renal disease. Clin Transplant. 2004;18:94–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1399-0012.2003.00132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herrero JI, Lucena JF, Quiroga J, et al. Liver transplant recipients older than 60 years have lower survival and higher incidence of malignancy. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:1407–1412. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6143.2003.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levy MF, Somasundar PS, Jennings LW, et al. The elderly liver transplant recipient: A call to caution. Ann Surg. 2001;233(1):107–113. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200101000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aduen JF, Sujay B, Dickson RC, et al. Outcomes after liver transplant in patients ages 70 years or older compared with those younger than 60 years. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(11):973–978. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60667-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lipshutz GS, Hiatt J, Ghobrial, et al. Outcome of liver transplantation in septuagenarians. Arch Surg. 2007;142(8):775–784. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.8.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fruhauf NR, Fischer-Frohlich CL, Kutschmann M, et al. Joint impact of donor and recipient parameters on the outcome of liver transplantation in Germany. Transplantation. 2011;92(12):1378–1384. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318236cd2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alamo JM, Barrera L, Marin LM, et al. Results of liver transplantation with donors older than 70 years: A case-control study. Transplant Proc. 2011;43(6):2227–2229. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Faber W, Seehofer D, Puhl G, et al. Donor age does not influence 12-month outcome after orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2011;43(10):3789–3795. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sampedro B, Cabezas J, Febrega E, et al. Liver transplantation with donors older than 75 years. Transplant Proc. 2011;43(3):679–682. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cortes L, Campillo A, Fiteni I, et al. Liver transplanted patients with donors older than 60 years require more hospital resources. Transplant Proc. 2011;43(3):735–736. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asrani SK, Lim YS, Therneau TM, et al. Donor race does not predict graft failure after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2010 Jun;138(7):2341–2347. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Layden JE, Cotler SJ, Grim SA, et al. Impact of donor and recipient race on survival after hepatitis C-related liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2012;93:444–449. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182406a94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Forman LM, Lewis JD, Berlin JA, et al. The association between hepatitis C infection and survival after orthotopic liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2002 Apr;122(4):889–896. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baid S, Cosimi AB, Farrell ML, et al. Posttransplant diabetes mellitus in liver transplant recipients: risk factors, temporal relationship with hepatitis C virus allograft hepatitis, and impact on mortality. Transplantation. 2001 Sep 27;72(6):1066–1072. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200109270-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.John PR, Thuluvath PJ. Outcome of liver transplantation in patients with diabetes mellitus: A case-control study. Hepatology. 2001 Nov;34(5):889–895. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.29134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shields PL, Tang H, Neuberger JM, et al. Poor outcome in patients with diabetes mellitus undergoing liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1999 Aug 27;68(4):530–535. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199908270-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmitt TM, Kumer SC, Al-Osaimi A, et al. Combined liver-kidney and liver transplantation in patients with renal failure outcomes in the MELD era. Transpl Int. 2009 Sep;22(9):876–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Menon KVN, Nyberg SL, Harmsen WS, et al. MELD and other factors associated with survival after liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(5):819–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nair S, Verma S, Thuluvath PJ. Pretransplant renal function predicts survival in patients undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2002;35:1179–1185. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gonwa TA, McBride MA, Anderson K, et al. Continued influence of preoperative renal function on outcome of orthotopic liver transplant (OLTX) in the US: Where will MELD lead us? Am J Transplant. 2006 Nov;6(11):2651–2659. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Totsuka E, Fung JJ, Hakamada, et al. Synergistic effect of cold and warm ischemia time on postoperative graft function and and outcome in human liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2004 Sep;36(7):1955–1958. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stahl JE, Kreke JE, Schaefer AJ, et al. Consequences of cold-ischemia time on primary nonfunction and patient and graft survival in liver transplantation: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2008 Jun 25;3(6):e2468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bloom RD, Reese PP. Chronic kidney disease after nonrenal solid-organ transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007 Dec;18(12):3031–3041. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007040394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gonwa TA, Jenning L, Mai ML, et al. Estimation of glomerular filtration rates before and after orthotopic liver transplantation: Evaluation of current equations. Liver Transpl. 2004 Feb;10(2):301–309. doi: 10.1002/lt.20017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Salerno F, Gerbes A, Gines P, et al. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84:662–670. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.107789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Orlando R, Mussap M, Plebani M, et al. Diagnostic value of plasma cystatin C as a glomerular filtration marker in decompensated liver cirrhosis. Clin Chem. 2002;48:850–858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]