Abstract

Background:

The immunohistochemical features of fetal haemoglobin cells and their distribution patterns in solid tumours, such as colorectal cancer and blastomas, suggest that fetal haemopoiesis may take place in these tumour tissues. These locally highly concentrated fetal haemoglobin (HbF) cells may promote tumour growth by providing a more efficient oxygen supply.

Methods and results:

Biomarkers of HbF were checked in transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the urinary bladder, assessing this as a new parameter for disease management. Fetal haemoglobin was immunohistochemically examined in tumours from 60 patients with TCC of the bladder. Fetal haemoglobin erythrocytes and erythroblasts were mainly clonally distributed in proliferating blood vessels and not mixed with normal haemoglobin erythrocytes. The proportion of such HbF blood vessels could reach more than half of the total number of vessels. There were often many HbF erythroblasts distributed in one-cell or two-cell capillaries and present as 5–15% of cells in multi-cell vessels. This suggests a local proliferation of HbF-cell progenitors. Fetal haemoglobin cells were prominently marking lower grades of tumours, as 76% (n=21) of the patients with G1pTa were HbF+, whereas only 6.7% (n=30) of the patients with G3pT1-pT2a were HbF+.

Conclusion:

Our results suggest that HbF, besides being a potential new marker for early tumour detection, might be an essential factor of early tumour development, as in fetal life. Inhibiting HbF upregulation may provide a therapeutic target for the inhibition of tumour growth.

Keywords: HbF, fetal haemoglobin, bladder cancer, fetal haemopoiesis

Systemic, high, whole blood concentration of fetal haemoglobin (HbF) is a well-established feature of haematological and solid tumours (Sheridan et al, 1976; Wolk et al, 1988, Rautonen and Mari, 1990). However, there is evidence suggesting local proliferation of HbF cells in tumour tissues. This was serologically demonstrated in lymphoma, ovarian cancer, brain cancer and other cancers by a high plasma HbF concentration independent of the whole blood concentration (Wolk et al, 1999). The same was also immunohistochemically shown in colorectal tumours (Wolk et al, 2006), as well as in blastomas (Wolk et al, 2007), by high concentrations of HbF erythroid cells, distributed as separated clusters rather than mixed with the normal erythrocytes, in blood vessels. To investigate this trait further, we decided to examine HbF in transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the urinary bladder in relation to the grade and stage of the disease. Although new markers for TCC have been evaluated during the past decade in order to improve management, they have not replaced traditional methods of urine cytology, although this is limited by its low sensitivity (Mukhtar and Perry, 2011). The most promising of these new techniques involve specific protein immunoassay (Stoeber et al, 2002) or molecular (Miyake et al, 2010) and genomic (Wang et al, 2009) biomarkers and require complicated techniques, which are not yet compatible with clinical practice. Fetal haemoglobin, however, if proved a suitable marker for TCC, might be easily evaluated serologically in blood or urine and by immunohistochemistry in tumour biopsies.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The study was conducted in the Blizard Institute, Core Pathology Group, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, using archival and stored materials. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the East London and City Health Authority. Histopathological specimens from bladder TCC patients were selected from the archive of the Department of Histopathology, the Royal London Hospital. The grade and stage of tumours were derived from records and reviewed for the blocks studied. The study comprised 60 patients, of whom 9 were women. The patients’ age range was 43–97 years (median=76); the grade distribution was as follows: 21 patients=G1, 8=G2, 30=G3 and 1=in situ TCC. Five controls of non-malignant bladder tissues were examined in parallel. No chemotherapy treatment was given at least 6 months preceding excision of the specimens.

Immunohistochemical staining

We used the peroxidase-labelled avidin–biotin method (Hsu and Raine, 1984). Formalin-fixed, paraffin wax-embedded cross-sections were cut at 3 μm, dewaxed, and then blocked for endogeneous peroxidase with 3% H2O2 in water for 15 min, and washed for 5 min in water and then for 5 min in TBS (0.05 tris buffered saline) wash buffer (Dako A/S, Glostrup, Denmark). The following incubation steps were used: (1) blocking with normal rabbit serum, diluted 1 : 5 for 30 min; (2) incubation with primary antibody, that is, affinity-purified sheep anti-human HbF (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), diluted 1 : 400 for 60 min; (3) incubation with secondary antibody, i.e., biotinylated rabbit anti-sheep IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), diluted 1 : 150 for 30 min; (4) incubation with ready-to-use streptavidin–biotin complex (RTU Vectastain Elite ABC, Vector Laboratories) for 30 min; and (5) incubation with DAB solution (chromogen; DAB kit, Vector Laboratories) for 4 min. The sections were then washed for 5 min in running water, automatically counterstained with Gill's haematoxylin, blue-differentiated, dehydrated and mounted. Between steps (1) through (4), the sections were washed in TBS wash buffer for 5 min. Staining was confirmed by two controls, where in step (2) we used the same anti-human HbF absorbed with HbF as negative control and human HbF absorbed with normal haemoglobin (HbA) as positive control. Fetal haemoglobin and HbA were prepared from the corresponding red cell lysates, insolubilised by the aid of gluteraldehyde (Wolk and Kieselstein, 1983) and then two volumes of anti-HbF were shaken at room temperature for 12 h, with one volume of either of those absorbents. The supernatants were then saved for control staining in place of the primary antibody.

Results

The criteria for positivity were as follows: (1) proliferating fine vessels with 100% HbF blood cells, distributed throughout the section; and (2) larger blood vessels with >50% HbF blood cells. Negative cases were sections without HbF blood cells, or with occasional <1%–5% HbF blood cells. As shown in Table 1, the percentage of HbF+ tumours was much higher in the noninvasive, low-grade G1 group (76%) than in the high-grade G3 group (6.7% ), whereas in the G2 group it was intermediate (50%).

Table 1. Ratios of positive HbF (HbF+) and negative HbF (HbF−) patients in different grades of TCC (%).

|

HbF+

|

HbF− |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | Total no. of patients | Stage distribution | Total no. of patients | Stage distribution | ||||||||

| pTa | 1 | 1a | 2 | 2a | pTa | 1 | 1a | 2 | 2a | |||

| G1 | 16 (76) | 16 | 5 (24) | 5 | ||||||||

| G2 | 4 (50) | 2 | 2 | 4 (50) | 4 | |||||||

| G3 | 2 (6.7) | 1 | 1 | 28 (93.3) | 14 | 1 | 1 | 12 | ||||

Abbreviation: TCC=transitional cell carcinoma.

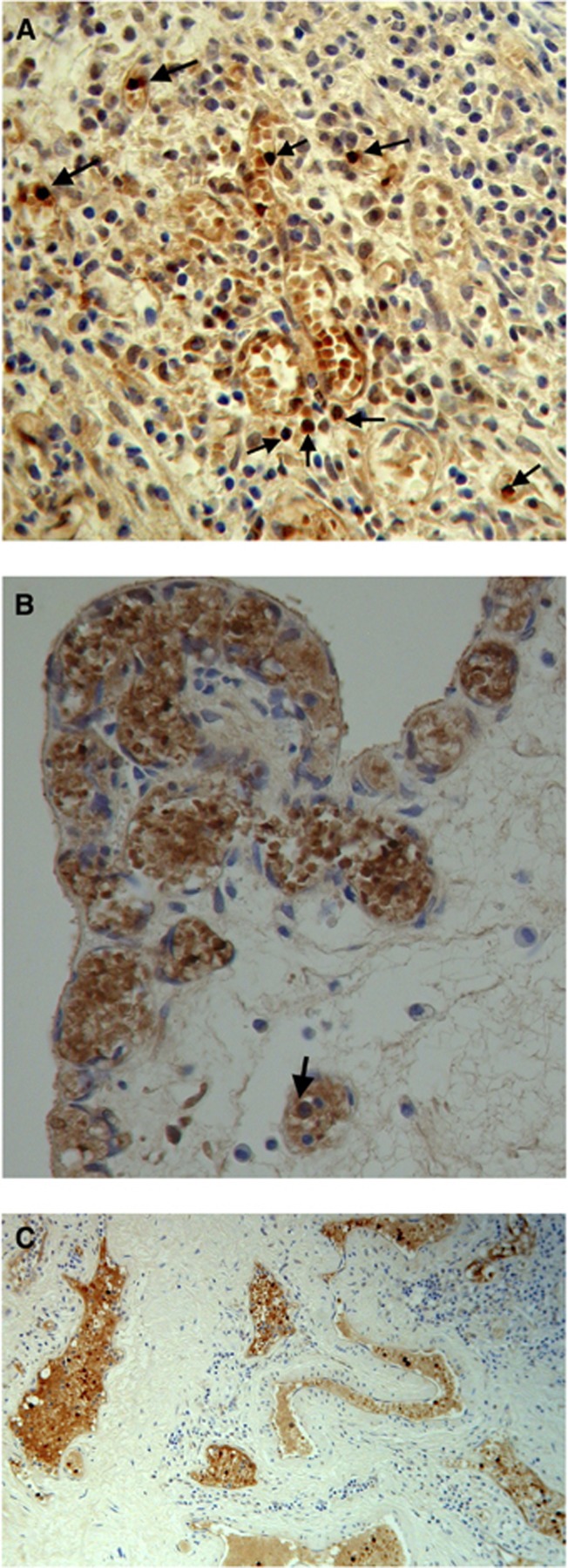

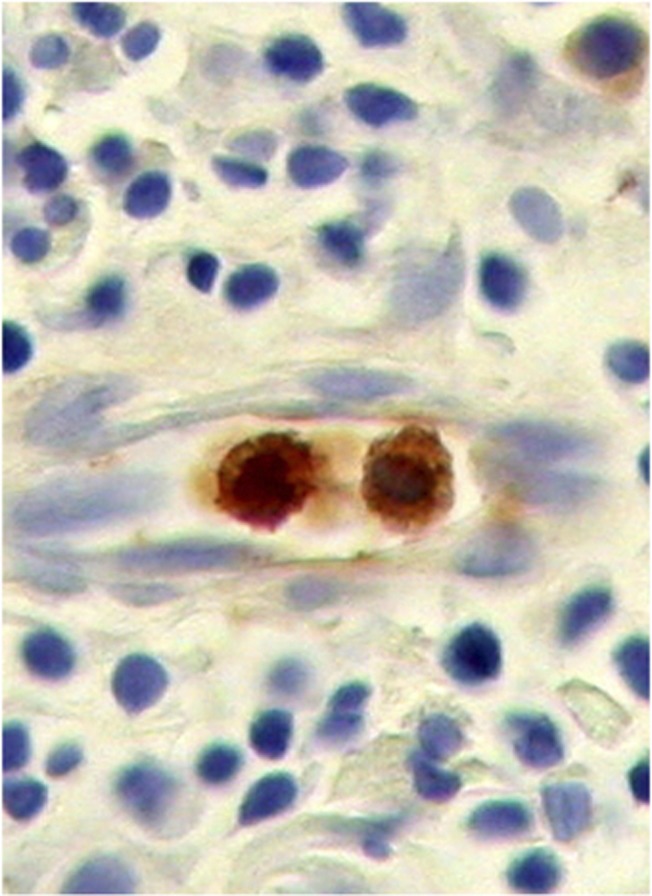

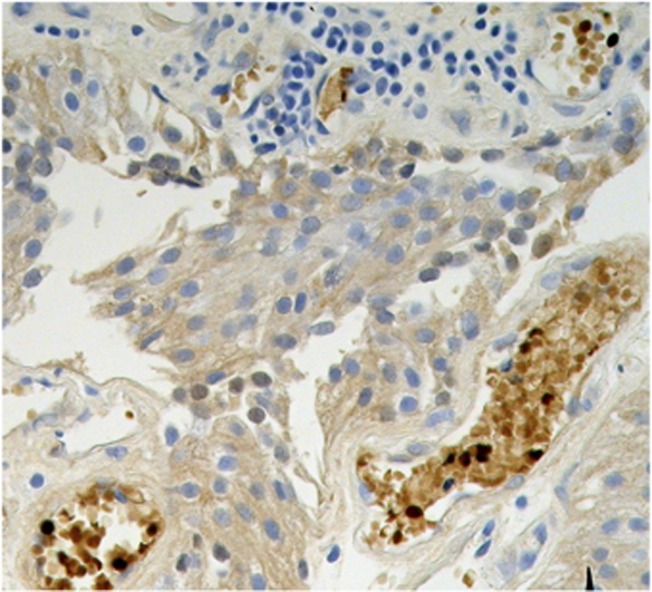

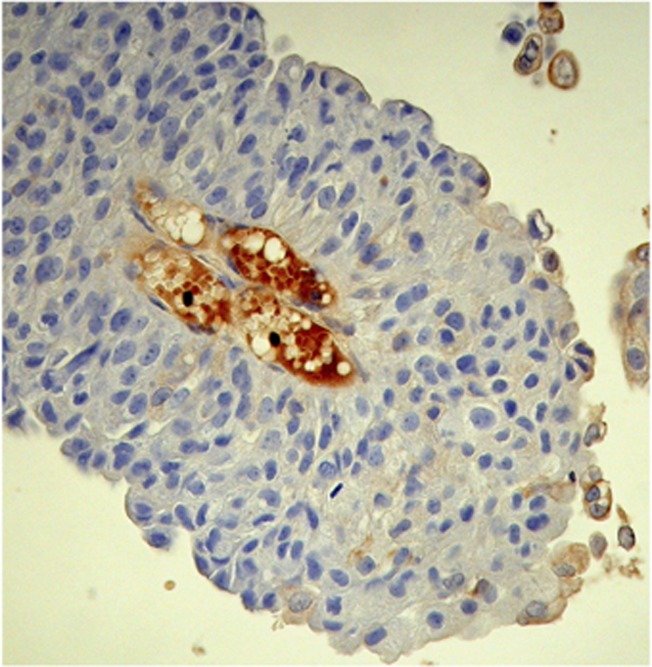

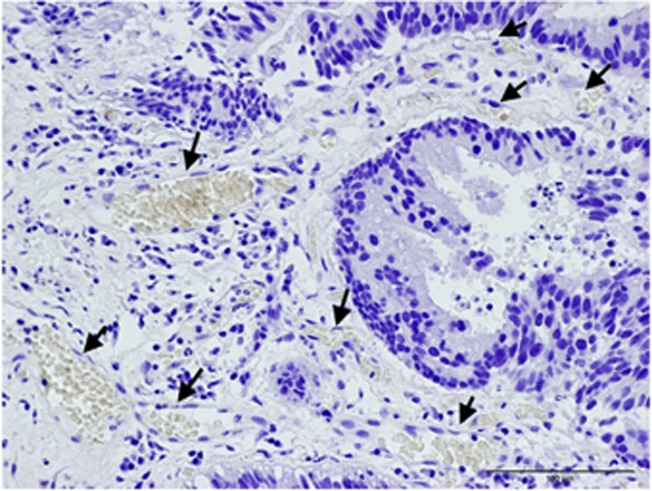

Fetal haemoglobin blood cell distribution is given in Table 2, in which a distinction is made between three kinds of blood vessels: (1) with adult haemoglobin (HbA) blood cells, (2) with a mixed population, including 10–40% HbF cells and (3) with predominantly HbF blood cells, >50% HbF cells. As shown in this table, the percentages of HbF+ vessels were, in most cases, over 50% (Figures 1A–C). Proliferation of HbF cells was indicated by nucleated (erythroblast and proerythroblast) cells filling one- or two-cell capillaries (Figure 2) or mixed with the HbF erythrocytes (Figures 1, 3 and 4). As shown in Table 2, the HbF blood vessels were distributed within the tumour (Figures 3 and 4) and in the lamina propria (Figures 1A–C), where the most intensive proliferation of fine blood vessels was noted. The HbF and the non-HbF blood vessels were distributed in separated areas throughout the sections. Proliferation of blood vessels with non-HbF blood cells, although present in low-grade G1 patients, was most prominent between the invasive tumour cells of high-grade G3 patients (Figure 5), where no vessels with HbF cells were observed.

Table 2. Distribution of blood vessels containing different proportion of HbF blood cells, in HbF+ TCC patients (%).

| Patient no. | Number of vessels with non-HbF cells | Number of vessels with mixed (HbF+ and HbF−) cells | Number of vessels with HbF+ cells | Proliferation of HbF cell vessels | HbF cell vessels between tumour cells | HbF cell vessels in lamina propria | Nucleated HbF cells | Pathological grade/stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 104 (19) | 150 (28) | 288 (53) | + | + | + | +(15) | G1pTa, no invasion |

| 2 | 22 (18) | 3 (2.4) | 98 (78.6) | + | + | + | +(5–10) | G1pTa, no invasion |

| 3 | 19 (12) | 47 (29) | 95 (59) | + | + | + | +(<5) | G1pTa, no invasion |

| 4 | 5 (7) | ND | 65 (93) | + | + | + | +(2–10) | G1pTa, no invasion |

| 5 | 32 (31) | 12 (11.5) | 60 (57.5) | + | + | + | +(10) | G1pTa, no invasion |

| 6 | 66 (39) | 56 (33) | 46 (31) | − | − | + | ND | G1pTa, no invasion |

| 7 | 5 (12) | 8 (19) | 30 (69) | + | − | + | +(>15) | G1pTa, no invasion |

| 8 | 27 (47) | ND | 30 (53) | − | + | − | ND | G1pTa, no invasion |

| 9 | 1 (3) | ND | 29 (97) | − | − | + | ND | G1pTa, no invasion |

| 10 | 6 (18) | ND | 28 (72) | + | + | − | +(14) | G1pTa, no invasion |

| 11 | 21 (51) | ND | 20 (49) | − | − | + | +(10–20) | G1pTa, no invasion |

| 12 | ND | ND | 19 (100) | + | + | − | +(7) | G1pTa, no invasion |

| 13 | 9 (30) | 9 (30) | 12 (40) | − | + | + | ND | G1pTa, no invasion |

| 14 | 2 (11) | 4 (22) | 12 (67) | − | + | − | ND | G1pTa, no invasion |

| 15 | 2 (22) | ND | 7 (78) | − | + | − | ND | G1pTa, no invasion |

| 16 | 18 (82) | ND | 4 (18) | − | + | − | ND | G1pTa, no invasion |

| 17 | 101 (33) | 50 (17) | 151 (50) | + | + | + | +(<5) | G2pTa, no invasion |

| 18 | 60 (33) | 42 (23) | 80 (44) | + | + | + | +(5) | G2pT1, inv lamina propria |

| 19 | ND | ND | 20 (100) | − | + | − | ND | G2pTa, no invasion |

| 20 | 70 (42) | 32 (19) | 65 (39) | + | + | − | +(10) | G2pT1, inv lamina propia |

| 21 | 6 (60) | ND | 4 (40) | − | − | + | ND | G3pT1, inv lamina propria |

| 22 | 4 (33) | ND | 8 (67) | − | − | + | ND | G3pT2a, inv lamina propria |

Abbreviations: HbF=fetal haemoglobin; ND=not detected; TCC=transitional cell carcinoma.

Figure 1.

Stages in proliferation of blood vessels with HbF cells in lamina propria of G1 TCC. Arrows indicating nucleated HbF progenitor cells: (A) clusters of HbF cells forming into fine vessels with many foci of nucleated HbF progenitor cells. (B) High density of small proliferating blood vessels. (C) Larger blood vessels spreading throughout the lamina propria.

Figure 2.

Small capillary with two HbF erythroblasts.

Figure 3.

Fetal haemoglobin cells, including nucleated (dark) cells, within tumour cells of G1 TCC.

Figure 4.

Fetal haemoglobin cells including nucleated (dark) cells, within tumour cells of G2 TCC.

Figure 5.

G3 TCC tumor with proliferating blood vessels (arrows) filled with normal Hb blood cells.

Five control biopsies from patients suspected of cancer, which were normal, were all without HbF blood cells.

Discussion

Local proliferation of HbF blood cell progenitors within the tumour is likely to be the main mechanism responsible for the high concentration of HbF blood cells. The histological picture shows multiple nucleated HbF cells (Figure 1, Table 2), sometimes filling up small capillaries (Figure 2), and proliferative patterns of fine to bigger blood vessels, filled predominantly with HbF cells apart from the normal Hb vasculature, probably due to the local fetal haemopoiesis in the tumour tissue. The extremely high concentration of blood vessels with HbF cells throughout TCC bladder tissue makes the bladder erythroid blood supply predominantly a fetal one. Owing to its high oxygen affinity, HbF might have a particular role in supporting cancer growth by providing an efficient oxygen delivery to the cells, as it does in fetal tissues during gestation (Carlson, 1988; Manca and Masala, 2008). Fetal haemoglobin (HbF) gene upregulation might thus be an important factor in supporting low-grade tumours, and it is possible that its inhibition may help to arrest the malignant process at an early stage. This is relevant to therapeutic strategies for tumours, aimed at angiogenesis, which is an important strategy in cancer therapy (Wu et al, 2008; Goel et al, 2011). We therefore suggest that the reduction of HbF cells inside tumour vasculature, along with inhibiting proliferation of the unique endothelial cells of the tumour, might be a useful approach.

Despite many studies having been conducted, the molecular mechanism of HbF regulation is not completely understood. However, in the silencing of γ-genes expression in normal adults, there is thought to be a fundamental role of DNA methylation (Lavelle, 2004; Saunthararajah et al, 2004; Sankaran, 2011). Consequent to methylation, there is induction of histone deacetylation of the chromatin, causing a closed chromatin configuration around the methylated sequences, which maintain silencing of those genes (Lavelle, 2004). Methods for restoring histone deacetylation might be useful in downregulation of HbF and reduction of HbF cell concentration in tumour tissues to normal levels. These might include reactivation of the enzymes DNA methyl transferase (DNMT) and histone de-acetylase (HDAC) in those erythroid cells progenitors, as inhibitors of these enzymes are used to upregulate HbF, therapeutically (Saunthararajah et al, 2004) for DNMT or experimentally (Witt et al, 2003) for HDAC. Reactivation of HbF has been shown to be mediated by certain signalling mechanisms that activate γ-globin genes via upregulation of transcription factors. These signalling mechanisms include activation of receptor tyrosine kinase CD117 (c-kit) on the surface of erythroid progenitor cells by stem cell factor (c-kit ligand), which has a key role in HbF reactivation in adult life (Wojda et al, 2003; Bhnu et al, 2004; Gabbianelli et al, 2010). Inhibitors of that signalling pathway, such as PD98059 (Bhnu et al, 2004), might be used to reduce the concentration of erythroid HbF cells where they may support cancer growth. Another approach to downregulation of HbF was shown in leukaemia cell lines, in which the concentration of HbF decreased to 15–5% of the control upon inhibition of the P-glycoprotein drug efflux pump (P-gp) (Fyrberg et al, 2011), indicating a link between P-gp and the induction of HbF.

The high incidence of blood vessels with predominant HbF erythroid cells in non-invasive low-grade tumours of the bladder suggests HbF as a potential prognostic marker in early stages of the disease. The use of HbF as such a marker requires larger-scale observation in TCC, as well as in other solid tumours. Evaluation of bladder HbF could be facilitated by measuring its concentration in plasma or urine, in order to avoid invasive procedures. We have previously shown that HbF is a potential systemic blood marker in these patients, as all 10 patients who were serologically examined had elevated concentrations of HbF in the blood (Wolk et al, 1988, 1991). It will be important to scrutinise the incidence and biological behaviour of a range of tumours, including bladder tumours, in light of the increasing use of drugs to induce HbF therapeutically.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the technical assistance of C Evagora, P levey, R Carrol and M Child from Queen Mary University of London ICMS/Pathology Group, The Royal London Hospital.

Footnotes

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bhnu NV, Trice TA, Lee YT, Miller JL (2004) A signaling mechanism for growth-related expression of fetal hemoglobin. Blood 103: 1929–1933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson BM (1988) The development of the circulatory system. In Patten's Foundations of Embryology, Dolinger E, Maisel J (eds). pp 594. McGraw-Hill: New York [Google Scholar]

- Fyrberg A, Peterson C, Kagedal B, Lotfi K (2011) Induction of fetal hemoglobin and ABCB1 gene exspression in 9-β-D-arabinofuranosylguanine-resistant MOLT-4 cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 68: 583–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbianelli M, Testa U, Morsilli O, Pelosi E, Saulle E, Petrucci E, Casteli G, Giovinazzi S, Mariani G, Fiori ME, Bonanno G, Massa A, Corce CM, Fontana L, Peschele C (2010) Mechanism of human Hb switching: a possible role of the kit receptor/miR 221-222 complex. Haematologica 95: 1253–1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel S, Duda DG, Xu L, Munn LL, Boucher Y, Fukumura D, Jain RK (2011) Normalization of the vasculature for treatment of cancer and other diseases. Physiol Rev 9: 1071–1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu Sb, Raine L (1984) The use of avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) in diagnostic and research pathology. In Advances in Immunochemistry, Delellis Ra (ed). pp 31–42. Mason: New York [Google Scholar]

- Lavelle DE (2004) The molecular mechanism of fetal hemoglobin reactivation. Semin Hematol 41(4, suppl 6): 3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manca L, Masala B (2008) Disorder of synthesis of human fetal hemoglobin. IUBMB Life 60: 94–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar S, Perry M JA (2011) Future prospects for bladder cancer biomarkers. Brit J Urol Int 108: 1336–1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake M, Sugano K, Sugino H, Imai K, Mutsumoto E, Maeda K, Fukozono S, Ichikawa H, Kawashima K, Hirabayashi K, KJodama T, Fujimoto H, Kakizoe T, Kanai Y, Fujimoto K, Hirao Y (2010) Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutation in voided urine is a useful diagnostic marker and significant indicator of tumor recurrence in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Cancer Sci 101: 250–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rautonen J, Mari AS (1990) Initial blood fetal hemoglobin concentration is elevated and is associated with prognosis in children with acute lymphoid or myeloid leukemia. Blut 61: 17–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaran VG (2011) Targeted therapeutic strategies for fetal hemoglobin induction. Heamatol Am Soc Heamatol Educ Program 2011: 459–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunthararajah Y, Lavelle D, DeSimone J (2004) DNA hypo-methylation agents and sickle cell disease. Brit J Haematol 126: 629–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan BL, Weatherhall DJ, Clegg JB, Prichard J, Wood WG, Challender ST, DUrrant IJ, McWhirter WR, Ali M, Partridge JW, Thompson EN (1976) The patterns of fetal haemoglobin production in leukaemia. Brit J Haematol 32: 487–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeber K, Swinn R, Prevost AT, de Clive-Lowe P, Halsall I, Dilworth SM, Marr J, Turner WH, Bullock N, Doble A, Hales CN, Williams GH (2002) Diagnosis of genito-urinary tract cancer by detection of minichromosome maintenance 5 protein in urine sediments. J Natl Cancer Inst 94: 1071–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Morris DS, Tonlis SA, Lonigro RJ, Tsodikov A, Mehra R, Giorando TJ, Kunjo LP, Lee CT, Weizer AZ, Chinaian AM (2009) Development of a multiplex quantitative PCR signature to predict progression in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cancer Res 69: 3810–3818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt O, Monkemeyer S, Roenndahl G, Erdlenbruch B, Reinhardt D, Kanbach K, Pekrun A (2003) Induction of fetal hemogloboin expression by the histone deacetylase inhibitor ampicin. Blood 101: 2001–2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojda U, Leigh KR, Njoroge JM, Jackson KA, Natarajan B, Stitely M, Miller JL (2003) Fetal hemoglobin modulation during human erythropoiesis: stem cell factor has “late” effects related to the expression pattern of CD117. Blood 101: 492–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk M, Kieselstein M (1983) Graded hemagglutination inhibition for quantification of human fetal hemoglobin. Clin Chem 29: 1372–1375 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk M, Kiesekstein M, Brufman G (1988) Evaluation of fetal hemoglobin in various malignancies with reference to the patients' age. Tumor Biol 9: 95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk M, Kieselstein M, Ben-Dor CG, Brufman G (1991) Fetal Hemoglobin screening in whole blood and in plasma of cancer patients. Tumor Biol 12: 45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk M, Newland AC, Dela Salle B, Peleg M, Brufman G (1999) Refinement of plasma fetal hemoglobin (HbF) measurements, as related to whole blood HbF, in cancer patients. J Tumor Marker Oncol 14: 115–124 [Google Scholar]

- Wolk M, Martin JE, Reinus C (2006) Development of fetal haemoglobin-blood cells (F cells) within colorectal tumour tissues. J Clin Pathol 59: 598–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk M, Martin JE, Nowicki M (2007) Foetal haemoglobin-blood cells (F-cells) as a feature of embryonic tumours (blastemas). Brit J Cancer 97: 412–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H-C, Huang C-T, Chang D-K (2008) Anti-angiogenic therapeutic drugs for treatment of human cancer. J Cancer Mol 4: 37–45 [Google Scholar]