Abstract

Substrates used to culture human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) are typically 2-dimensional (2-D) in nature, with limited ability to recapitulate in vivo-like 3-dimensional (3-D) microenvironments. We examined critical determinants of hESC self-renewal in poly-d-lysine-pretreated synthetic polymer-based substrates with variable microgeometries, including planar 2-D films, macroporous 3-D sponges, and microfibrous 3-D fiber mats. Completely synthetic 2-D substrates and 3-D macroporous scaffolds failed to retain hESCs or support self-renewal or differentiation. However, synthetic microfibrous geometries made from electrospun polymer fibers were found to promote cell adhesion, viability, proliferation, self-renewal, and directed differentiation of hESCs in the absence of any exogenous matrix proteins. Mechanistic studies of hESC adhesion within microfibrous scaffolds indicated that enhanced cell confinement in such geometries increased cell-cell contacts and altered colony organization. Moreover, the microfibrous scaffolds also induced hESCs to deposit and organize extracellular matrix proteins like laminin such that the distribution of laminin was more closely associated with the cells than the Matrigel treatment, where the laminin remained associated with the coated fibers. The production of and binding to laminin was critical for formation of viable hESC colonies on synthetic fibrous scaffolds. Thus, synthetic substrates with specific 3-D microgeometries can support hESC colony formation, self-renewal, and directed differentiation to multiple lineages while obviating the stringent needs for complex, exogenous matrices. Similar scaffolds could serve as tools for developmental biology studies in 3-D and for stem cell differentiation in situ and transplantation using defined humanized conditions.—Carlson, A. L., Florek, C. A., Kim, J. J., Neubauer, T., Moore, J. C., Cohen, R. I., Kohn, J., Grumet, M., Moghe, P. V. Microfibrous substrate geometry as a critical trigger for organization, self-renewal, and differentiation of human embryonic stem cells within synthetic 3-dimensional microenvironments.

Keywords: fibrous scaffolds, poly-d-lysine, tissue engineering

Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) hold promise for regenerative medicine and drug discovery applications due to their pluripotency and capacity for indefinite self-renewal (1, 2). However, the mechanisms governing hESC self-renewal and differentiation are insufficiently understood, hindering our ability to efficiently and reproducibly expand and differentiate these cells (3). Undifferentiated hESCs are typically expanded and maintained on fibroblast feeder layers or Matrigel-coated dishes, which introduce variability into cultures and may cause hESCs to acquire nonhuman components, limiting applicability for future clinical applications (4). Recently, several successful approaches for defining the culture medium (5, 6) and/or substrates (6–9) for hESC expansion have been reported. It is well established that hESC self-renewal can be sensitively regulated by several aspects of the stem cell niche, including soluble factors, cell-cell contacts, and interactions with specific extracellular matrix (ECM) components (10). The role of geometric features of the 3-dimensional (3-D) hESC microenvironment has not been well appreciated for their ability to influence hESC behaviors in vitro. Most culture systems for hESCs to date involve 2-dimensional (2-D) substrates, which fail to adequately recapitulate the complex 3-dimensional (3-D) microenvironments these cells inhabit during embryonic development (11, 12).

A growing body of literature reports that cell behaviors are markedly influenced by 3-D substrate geometries, including adhesion, migration, morphogenesis, proliferation, gene expression, matrix remodeling, and differentiation (13–18). Several recent studies demonstrated hESC self-renewal (19–21) or differentiation (17, 22–25) in 3-D scaffolds that aimed to mimic different aspects of the stem cell niche. However, the role of 3-D scaffold geometry in directing hESC colony formation, self-renewal, and differentiation has yet to be investigated. In addition, the mechanisms governing hESC survival and self-renewal within 3-D substrates have not been studied.

In this study, we investigated the role of the geometry of synthetic scaffolds as a possible determinant of hESC survival, colony formation, and self-renewal within 3-D substrates. To this end, we screened synthetic 2-D films and 3-D biomaterial scaffolds with variable geometries based on tyrosine-derived polycarbonates (26, 27) and evaluated their ability to support hESC colony formation when pretreated with a variety of ECM proteins and other cell-attachment factors. We identified a fully synthetic condition—scaffolds with fibrous geometry treated with poly-d-lysine (PDL)—that supports hESC colony formation, proliferation, and self-renewal similar to Matrigel-treated controls, in addition to supporting in situ differentiation to neurons, hepatic lineage cells, and smooth muscle cells (SMCs). This is in striking contrast to the same polymers presented as 2-D films or 3-D macroporous scaffolds and treated with PDL, which, like most synthetic 2-D substrates, fail to support hESC survival. We found that synthetic fibrous scaffolds pretreated with PDL enable optimal cell confinement that drives cellular matrix deposition and hESC survival and self-renewal. A corollary of our study is that completely synthetic 3-D substrates with fibrous topography can compensate for the stringent matrix requirements for hESC self-renewal in 2-D systems. This could have important implications in developing fully synthetic and defined 3-D systems for clinically relevant hESC expansion and differentiation or for studying hESC responses to extracellular stimuli in a more in vivo-like microenvironment free of exogenous ECM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Polymer substrate fabrication and characterization

Three different configurations of polymer substrates were fabricated: 2-D polymer films, macroporous scaffolds with nonfibrous geometry, and microfibrous scaffolds. The base polymer was poly(desaminotyrosyl tyrosine ethyl ester carbonate) (pDTEc), which was synthesized by Isochem North America LLC (Princeton, NJ, USA), as described previously (26).

The 2-D pDTEc films (2-DFilms) were prepared by spin-coating, as described previously (28). Three-dimensional macroporous pDTEc (3-DPorous) scaffolds with bimodal pore size distribution were fabricated by salt leaching and rapid, selective solvent crystallization, as described previously (29). Two types of microfibrous scaffolds were fabricated with different fiber diameters by electrospinning, similar to previously described methods (27). Cell-impermeable 2-D fibrous pDTEc (2-DFibrous) scaffolds with small fibers and pores, named for their pseudo-3-D geometry, and cell-permeable 3-D fibrous pDTEc (3-DFibrous) scaffolds with large fibers and pores were fabricated. Briefly, pDTEc was dissolved in 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 11% w/v (2-DFibrous) or in dichloromethane (DCM) at 18% w/v (3-DFibrous). Polymer solutions were electrospun from a +18-kV (2-DFibrous) or +24-kV (3-DFibrous) spinneret to a −6-kV rotating mandrel collector at 3 ml/h over a distance of 18 cm. A 30-kV dual-polarity power supply (Gamma High Voltage Research, Inc., Ormond Beach, FL, USA) regulated the voltage, and a programmable syringe pump (KD Scientific, Holliston, MA, USA) delivered polymer solution to the spinneret. The electrospinning procedure produced scaffolds with thicknesses ranging from 250 to 500 μm. Scaffolds were sterilized with ethylene oxide gas (AN-74i; Anderson Products, Haw River, NC, USA), and degassed under vacuum. Surface morphology of as-spun electrospun scaffolds was observed on an AMRAY 1830 I scanning electron microscope (SEM; AMRAY, Inc, Bedford, MA, USA) and fiber diameter was quantified by measuring 100 individual fibers from each scaffold using U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). Pore diameter was quantified for hydrated scaffolds that were fluorescently labeled by adsorbing with 1 μg/ml Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated bovine serum albumin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). High-resolution images were taken using a Leica TCS-SP2 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), and pore area was quantified using ImagePro Plus 5.1 (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA). Quantitative data are presented as means ± 95% confidence interval.

Preparation and surface treatment of polymer substrates

Electrospun 2-DFibrous and 3-DFibrous scaffolds and salt-leached 3-DPorous scaffolds were hydrated in PBS, punched into 6-mm-diameter discs, and placed into individual wells of 96-well tissue culture plates. For differentiation studies, scaffolds were affixed to 12-mm glass coverslips with a medical-grade silicon adhesive (Factor II, Lakeside, AZ, USA), secured in wells of 24-well plates with silicon O-rings, and hydrated in PBS. Prior to cell seeding, some scaffolds were adsorbed with PDL (10 μg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich), Matrigel (1/10 of the recommended concentration for 2-D culture; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), poly-l-lysine (PLL; 10 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich), poly-l-ornithine (PLO; 10 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich), human plasma fibronectin (10 μg/ml; BD Biosciences), human placental laminin (10 μg/ml), type 1 collagen (10 μg/ml; BD Biosciences), type IV collagen (10 μg/ml BD Biosciences), or recombinant human vitronectin (10 μg/ml, PeproTech, Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). After pretreatment, scaffolds were washed with PBS and equilibrated in mTeSR1 medium (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) containing 10 μM Y-27632 (EMD Biosciences, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The 2-DFilm substrates were placed into wells of a 24-well tissue culture plate, secured with silicon O-rings, and treated with PDL or Matrigel.

hESC culture, seeding, and differentiation on polymer substrates

NIH-approved hESC lines WA01 (H1) and WA09 (H9) from the WiCell Research Institute (Madison, WI, USA) were maintained under feeder-free conditions on Matrigel-coated dishes (BD Biosciences) in mTeSR1 maintenance medium for hESCs (Stem Cell Technologies), as described previously (30). Cells were routinely passaged every 5–7 d using 1 mg/ml dispase (BD Biosciences). hESCs were seeded into 3-D polymer substrates or onto 2-D controls at 9 × 104 cells/cm2 for 3-D substrates or at 3.33 × 104 cells/cm2 for 2-D controls in mTeSR1 containing Y-27632 by passaging with Accutase, according to previous reports (31, 32). Medium was replaced with mTeSR1 without Y-27632 12–24 h after seeding, and then changed daily thereafter for self-renewal studies.

Directed differentiation of hESCs in situ within 3-DFibrous scaffolds was initiated following 7 d of undifferentiated culture in mTeSR1 by adapting previously reported protocols for differentiation to neuronal cells (33, 34), hepatic-like cells (35), and SMCs (36). To generate neuronal cells, medium was changed to N2-SFM containing DMEM/F12 supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 1% nonessential amino acids (NEAAs), 1% N2 supplement, and 0.5% penicillin/streptomycin (pen/strep) (all from Invitrogen) for 7 d, followed by NDM, consisting of neurobasal medium supplemented with 1× B27 without vitamin A (Invitrogen), 10 ng/ml brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF, PeproTech) and 0.5% pen/strep for 5 d. To generate hepatic-like cells, medium was changed to RPMI 1640 medium (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) supplemented with 1× B27 supplement, 100 ng/ml activin A, 10 ng/ml hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) (both from PeproTech), 50 ng/ml Wnt-3a (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA), and 1% pen/strep for 3 d, followed by DMEM/F12 supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 20% Knockout Serum Replacement (Invitrogen), 1% NEAAs, 0.1 μM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), 1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich), and 1% pen/strep for 5 d, and IMDM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 1% ITS supplement (Invitrogen), 0.5 μM dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 ng/ml oncostatin-M (R&D Systems), and 1% pen/strep for 5 d. To generate SMCs, medium was changed to DMEM/F12 supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen), 2 mM l-glutamine, 1% NEAAs, 10 μM all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA; Sigma-Aldrich), and 1% pen/strep for 12 d.

hESC viability, colony formation, and proliferation analysis

hESC viability in fibrous scaffolds or salt-leached scaffolds was evaluated in each of our substrates by detecting intracellular esterase activity using calcein-AM (Invitrogen). Cell-containing scaffolds were incubated in PBS containing 1 μM calcein-AM for 30 min at 37°C. After incubation, scaffolds were washed with PBS, placed (inverted) into wells of a 96-well glass-bottom plate, and imaged immediately. Imaging was performed using a Leica SP2 confocal microscope using tile-scanning mode to image entire scaffolds (fibrous scaffolds). All images are projections of 3-D z-stacks.

Colony formation for hESCs in fibrous scaffolds was evaluated quantitatively by counting the number of calcein-AM-positive colonies observed in scaffolds with each of the tested pretreatments. hESC proliferation in fibrous scaffolds was determined by quantifying DNA content of cell-scaffold constructs at several time points using a CyQuant cell proliferation assay kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Graphs represent means ± sd.

Immunocytochemistry

hESC-scaffold constructs were prepared for indirect immunofluorescence after 7, 14, or 19 d of culture by fixing with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) and permeabilizing and blocking in blocking buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) and 4% normal goat serum (Invitrogen) in PBS. Primary antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer and incubated at 4°C overnight. Primary antibodies used include mouse anti-octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (Oct4), anti-stage-specific embryonic antigen 4 (SSEA-4), anti-tumor rejection antigen 1-60 (Tra-1-60), anti-integrin β1, and rat anti-integrin α6 (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), mouse anti-α-fetoprotein (AFP), and anti-α-smooth muscle actin (αSM-actin) (Sigma-Aldrich), and rabbit anti-laminin (Sigma-Aldrich), anti-collagen type I (AbCam, Cambridge, MA, USA), anti-collagen type 4 (Chemicon International Inc., Temecula, CA, USA), and mouse anti-TUJ1 (Covance, Princeton, NJ, USA). Samples were washed in PBS, then incubated in Alexa-Fluor 488 or 594 goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) diluted in blocking buffer for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were washed again with PBS, counterstained with 1 μg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI; Invitrogen) and mounted onto glass microscope slides using ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen) for imaging. Confocal images were acquired by a Leica SP2 laser-scanning confocal microscope, using reflectance to visualize scaffold fibers. Unless otherwise noted, images shown are maximum intensity projections of z-stacks. Infiltration depth of hESCs within fibrous scaffolds was quantified by acquiring optical cross-sections using a galvanometer stage and measuring the maximum infiltration depth of individual colonies using ImageJ. Graphs represent means ± sd.

Real-time quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from hESCs cultured in scaffolds using the RNEasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions, including treatment with RNase-free DNase to remove genomic DNA. A high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) containing random primers was used to reverse transcribe 200 ng total RNA from each sample to cDNA. TaqMan gene expression master mix and TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems) were used for template amplification of 10 ng cDNA/reaction. qRT-PCR was carried out on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems). Relative gene expression was calculated using the ΔΔCT method, normalizing to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as the endogenous control and undifferentiated hESCs in standard 2-D culture (on Matrigel-coated dishes in mTeSR1 medium) after 7 d as the reference sample. Graphs represent means ± sd. TaqMan gene expression assays for POU domain, class 5, transcription factor 1 (POU5F1; Hs03005111_g1), NANOG (Hs02387400_g1), telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT; Hs00162669_m1), AFP (Hs00173490_m1), α-smooth muscle actin (ACTA2; Hs00426835_g1), MAP2 (Hs00258900_m1), and GAPDH (4326317E) (all from Applied Biosystems) were used in these studies.

Laminin-blocking studies

The role of endogenously produced laminin on hESC adhesion to 3-DFibrous scaffolds was determined by blocking binding to laminin and evaluating the effects on initial cell adhesion. hESCs were seeded onto 3-DFibrous scaffolds as described previously in mTeSR1 with Y-27632 and either an anti-laminin 1 + 2 antibody (10 μg/ml, Millipore) or IgG control (AbCam). Medium was replaced with mTeSR1 without Y-27632 and containing anti-laminin 1 + 2 or IgG control 12 h after seeding. After an additional 12 h, the number of live cells present was quantified using Alamar Blue (Invitrogen). Data are normalized to the IgG control for each substrate, and represent means ± sd.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's HSD post hoc test. Comparisons with P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Fabrication and characterization of fibrous scaffolds with variable architectures

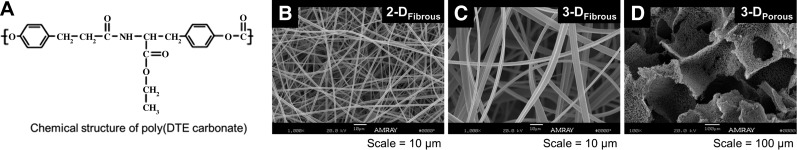

Polymer scaffolds fabricated from pDTEc (Fig. 1A) were found to yield variable architectures, as visualized by SEM (Fig. 1B–D). Quantitative characterization of electrospun scaffold configurations revealed significant differences in fiber diameter and pore diameter between the scaffold geometries, with fiber diameters of 1.09 ± 0.03 and 3.38 ± 0.17 μm, and effective pore diameters of 4.92 ± 0.1 and 13.9 ± 0.4 μm, for 2-DFibrous and 3-DFibrous scaffolds, respectively. Due to the differences in porosity, we expected the smaller-fiber scaffolds to be predominantly cell impermeable, and the larger-fiber scaffolds to be cell permeable. In contrast, the nonfibrous scaffold configurations (3-DPorous) had an average pore diameter of 247 ± 15 μm, which was much greater than that of the fibrous scaffolds.

Figure 1.

Fabrication and characterization of synthetic fibrous polymer scaffolds in different geometric configurations. Scaffolds were fabricated from pDTEc (A) into 2-DFibrous (B) and 3-DFibrous (C) configurations by electrospinning, and into 3-DPorous configurations by salt-leaching (D), yielding scaffolds with significantly different architectures.

Screen of matrix pretreatments and scaffold geometries that support hESC colony formation

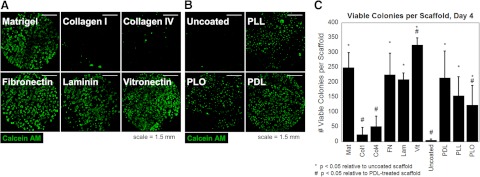

We examined a wide range of pretreatment conditions for fibrous scaffolds to assess the surface effects on hESC colony formation. As positive controls, natural ECM protein pretreatments, particularly, Matrigel, fibronectin, laminin, and vitronectin, supported enhanced levels of hESC colony formation, as assessed by calcein-AM staining and whole-scaffold confocal imaging, while collagen type I and collagen type IV did not support colony formation (Fig. 2A). A fully synthetic condition consisting of untreated polymer scaffolds supported minimal colony formation. In contrast, scaffolds treated with synthetic polycations PDL, PLL, and PLO supported extensive colony formation after 4 d of culture (Fig. 2B). Quantitative analysis of the number of viable colonies per scaffold after 4 d of culture revealed significantly enhanced colony formation in PDL-treated scaffolds relative to untreated or collagen-treated scaffolds, and no significant difference in the number of viable colonies between PDL and several natural matrices, including Matrigel (Fig. 2C). This suggests that synthetic fibrous substrates that are surface modified to be cationic may be sufficient to support hESC adhesion, survival, and colony formation in 3-D. Only substrates treated with PDL were retained for further studies, along with substrates treated with Matrigel as positive controls.

Figure 2.

Screen of natural and synthetic scaffold pretreatments. A, B) A variety of natural (A) and synthetic (B) pretreatments were adsorbed onto 3-DFibrous scaffolds to determine which would support hESC survival and colony formation. A) Natural ECM pretreatments Matrigel, fibronectin, laminin, and vitronectin supported extensive colony formation, as assessed by calcein-AM staining, while collagen type I and collagen type IV supported minimal hESC survival. B) Of the synthetic conditions, while uncoated scaffolds permitted minimal survival, we observed extensive colony formation in scaffolds treated with polycations PLL, PLO, and PDL. Images shown are of entire scaffolds. Scale bars = 1.5 mm. C) Quantification of the number of viable colonies per scaffold for each pretreatment reveals enhanced colony formation for PDL-treated scaffolds relative to untreated or collagen treated scaffolds, similar to Matrigel and other natural matrices. Graphs are means ± sd. Statistical significance was evaluated by ANOVA with a Tukey HSD post hoc test. *P < 0.05 vs. untreated scaffolds, #P < 0.05 vs. PDL.

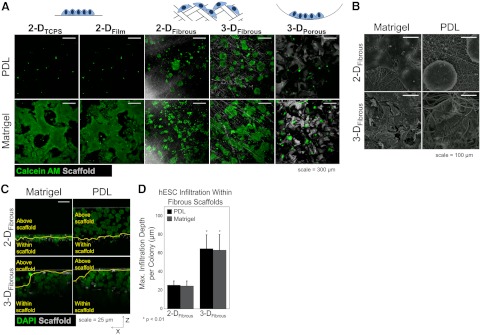

Next, we investigated whether a specific 3-D geometry was necessary for hESC retention on PDL-treated synthetic polymer substrates. We seeded hESCs onto pDTEc substrates in different 2-D and 3-D configurations to determine their ability to support hESC colony formation. We characterized the following substrates that were adsorbed with PDL or Matrigel: 2-D tissue culture polystyrene (2-DTCPS), 2-DFilm, 2-DFibrous, 3-DFibrous, and 3-DPorous (Fig. 3A). We found that all of the above substrates supported adhesion and colony formation when treated with Matrigel, as characterized by calcein-AM staining. However, only the 2-DFibrous and 3-DFibrous substrates supported hESCs in the absence of a matrix protein pretreatment, suggesting that the combination of high surface area and enhanced cell confinement afforded by fibrous polymer scaffolds is necessary for hESCs to adhere and form colonies. Thus, microfibrous substrate geometry is a key regulator of hESC survival and colony formation.

Figure 3.

Scaffold geometry regulates hESC colony formation in synthetic substrates. A) hESCs were seeded into polymeric substrates in a variety of configurations (2-DTCPS, 2-DFilm, 2-DFibrous, 3-DFibrous, 3-DPorous) to determine which geometries would support hESC colony formation under synthetic conditions. B) All geometric configurations supported hESCs when treated with Matrigel. However, only fibrous scaffold configurations, and not 2-D or 3-DPorous configurations, supported hESC colony formation when treated with PDL. The hESC colonies in scaffolds were visualized by SEM for PDL or Matrigel-treated 2-DFibrous and 3-DFibrous scaffolds, indicating infiltration only in 3-DFibrous scaffolds. C) The extent of 3-D colony organization was determined for 2-DFibrous and 3-DFibrous scaffolds when treated with PDL by quantifying the degree of infiltration within the fibrous scaffold structure. Nuclei were stained with DAPI and pseudo-colored green to aid in visibility. Yellow line on each image represents the top layer of scaffolds fibers (shown in white; horizontal white line is the coverslip used to hold the sample in place). Any nuclei below the yellow line are considered to have infiltrated within the scaffold. D) Quantitative measurements indicate that the more porous 3-DFibrous scaffolds supported significantly greater hESC infiltration than 2-DFibrous scaffolds, allowing for enhanced cell-cell and cell-matrix contact. Scale bars = 300 μm (A); 25 μm (B). Graphs are means ± sd. Statistical significance was evaluated by ANOVA with a Tukey HSD post hoc test. *P < 0.05.

We then investigated colony organization and infiltration within 2-DFibrous and 3-DFibrous scaffolds when treated with PDL or Matrigel. SEM images of hESCs on 2-DFibrous and 3-DFibrous scaffolds (Fig. 3B) suggest that hESCs remain primarily atop fibers when cultured on 2-DFibrous scaffolds, but infiltrate and organize around the scaffold fibers within 3-DFibrous scaffolds. Differences in colony morphology are observed for 2-DFibrous scaffolds with different pretreatments, in which colonies remain compact and spherical on PDL-treated scaffolds, but spread and flatten on Matrigel-treated scaffolds. However, these differences are not apparent in the 3-DFibrous scaffolds, which display similar colony morphologies and infiltration. We further evaluated the degree to which hESCs infiltrated and organized within the fibrous scaffold configurations by taking optical cross-sections of the cell-populated scaffolds (Fig. 3C) and quantified the infiltration depth below the top layer of scaffold fibers after 7 d of culture (Fig. 3D). For each image in Fig. 3B, the yellow line represents the top layer of fibers, with nuclei below the line considered to have infiltrated within the scaffold and nuclei above the line to be considered atop the fibers. These cross-sections confirm the differences in colony morphology observed between PDL and Matrigel-treated 2-DFibrous scaffolds and the similarities in morphology between both 3-DFibrous scaffold conditions. Quantification confirmed significantly enhanced infiltration into 3-DFibrous configurations relative to 2-DFibrous scaffolds regardless of pretreatment. Since this demonstrated enhanced 3-D organization within our 3-DFibrous scaffolds, we chose to use only this scaffold configuration for subsequent experiments.

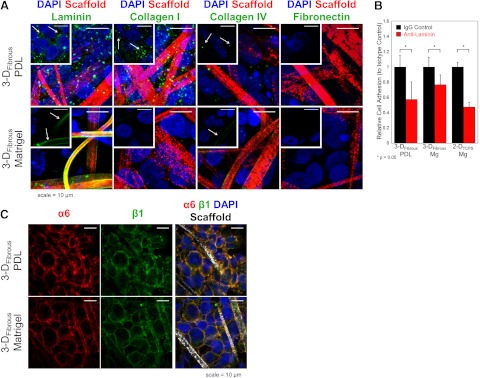

Substrate-mediated ECM production and its role in hESC adhesion to matrix-free 3-DFibrous scaffolds

We investigated the mechanisms by which hESCs maintained their phenotypes within the synthetic fibrous scaffolds and focused on the matrix remodeling of their microenvironment. We evaluated hESC ECM production by immunofluorescence studies of hESCs in PDL- or Matrigel-treated 3-DFibrous scaffolds for several key ECM proteins, including laminin, collagen type I, collagen type IV, and fibronectin, after 3 d of culture. hESCs in PDL-treated 3-DFibrous scaffolds produced significant levels of laminin and collagen type I, modest levels of collagen type IV, and minimal fibronectin (Fig. 4A). By contrast, hESCs in Matrigel-treated scaffolds produced minimal amounts of any of the ECM proteins screened (though extensive staining for laminin is seen on fibers, as this is a major component of Matrigel; Fig. 4A). Isotype controls were negative for both PDL- and Matrigel-treated scaffolds (not shown). This demonstrated that hESCs have the ability to populate fibrous microenvironments with endogenous matrix, and that this matrix deposition is differentially regulated based on the exogenous matrix cues already present.

Figure 4.

ECM production and remodeling by hESCs in synthetic fibrous scaffolds. A) hESCs produce high levels of laminin and collagen type I, and low levels of collagen type IV in PDL-treated 3-DFibrous scaffolds, but not in Matrigel-treated 3-DFibrous scaffolds, as indicated by immunocytochemistry. ECM deposition is observed surrounding cells in PDL-treated scaffolds, but is absent or localized only to fibers (which are adsorbed with laminin- and collagen IV-containing Matrigel) in Matrigel-treated scaffolds. Images are projections of z-stacks; insets are single confocal slices. B) hESC binding to laminin is critical for initial cell adhesion and survival, as indicated by functional blocking of adhesion to laminin, which reduces cell adhesion relative to controls, even in the absence of exogenous laminin (3-DFibrous PDL condition). Graphs represent means ± sd. Statistical significance was evaluated by ANOVA with a Tukey HSD post hoc test. *P < 0.05. C) In addition, hESCs highly express laminin binding integrins β1 and α6, with enhanced localization of staining along fibers in Matrigel-treated scaffolds relative to PDL-treated scaffolds. Images are single confocal slices. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Laminin is the most prevalent component of Matrigel, the current gold-standard ECM pretreatment for 2-D feeder-free culture of hESCs (6), and hESCs have been shown to highly express the laminin-binding integrin receptor pair α6β1 by numerous recent reports (37, 38). Thus, we hypothesized that hESC production and binding to laminin in PDL-treated scaffolds could be a key factor that permits hESCs to adhere and survive in the absence of exogenous ECM. We tested this hypothesis by functionally blocking laminin during the first 24 h of hESC seeding into PDL-treated 3-DFibrous scaffolds, Matrigel-treated 3-DFibrous scaffolds, and 2-DTCPS Matrigel-treated controls. We found that for all three conditions, inhibition of laminin significantly reduced the number of cells attached after 24 h, even in PDL-treated scaffolds that are free of exogenous ECM (Fig. 4B). This indicates that in 3-DFibrous scaffolds, antibody blocking of laminin during hESC seeding is sufficient to decrease attachment, even if exogenous laminin is deficient. In addition, we verified by immunocytochemistry that hESCs highly express integrins α6 and β1 in situ within 3-DFibrous scaffolds pretreated with either PDL or Matrigel (Fig. 4C), demonstrating the presence of the necessary integrin receptors for laminin engagement, regardless of the origin of laminin present. In addition, localization of integrin staining along scaffold fibers is pronounced in Matrigel-treated 3-DFibrous scaffolds relative to PDL-treated scaffolds, which is consistent with laminin being found predominantly along fibers in Matrigel-treated scaffolds, vs. laminin found throughout colonies in PDL-treated scaffolds.

Proliferation, self-renewal, and directed differentiation of hESCs in matrix-free fibrous scaffolds

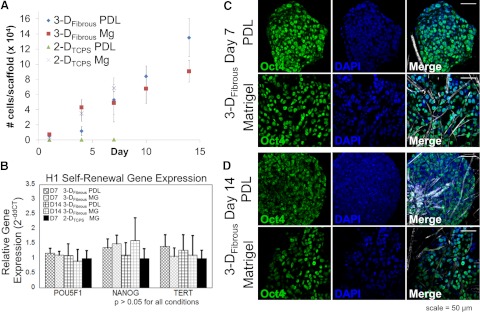

We sought to identify whether cells within the fibrous, synthetic substrates displayed other characteristic hESC behaviors, including proliferation, expression of self-renewal markers, and capacity for differentiation similar to Matrigel-treated substrates. We hypothesized that even in the absence of exogenous matrix, the enhanced 3-D organization, cell-cell contact, and cell-substrate contacts afforded by PDL-treated 3-DFibrous scaffolds would permit hESCs to retain these behaviors. We compared hESC self-renewal, proliferation, and differentiation over 14–19 d of culture within synthetic 3-DFibrous scaffolds, with Matrigel-treated scaffolds as controls. hESCs in PDL-treated scaffolds proliferated extensively, similar to 2-DTCPS and 3-DFibrous Matrigel-treated controls (Fig. 5A), and in contrast to 2-DTCPS PDL-treated substrates. Data for PDL and Matrigel-treated 2-DTCPS substrates was excluded beyond 7 d since there were either no cells remaining or cells had reached confluence, respectively. We also found that hESCs can self-renew for up to 14 d within PDL-treated 3-DFibrous scaffolds, similarly to Matrigel-treated 3-DFibrous scaffolds and 2-DTCPS substrates, based on gene expression of POU5F1, NANOG, and TERT (no statistical significant differences; P > 0.05; Fig. 5B), and expression of pluripotency marker Oct4 (Fig. 5C), as visualized by immunocytochemistry and confocal imaging. These behaviors were observed for both H1 (Fig. 5) and H9 (Supplemental Fig. S1) hESCs, demonstrating that these effects were not cell line-specific. In addition, both H1 and H9 cells expressed additional self-renewal surface markers Tra-1-60 and SSEA-4 within PDL-treated fibrous scaffolds (Supplemental Fig. S2).

Figure 5.

Fully synthetic PDL-treated 3-DFibrous fibrous scaffolds support hESC proliferation and self-renewal similar to Matrigel-treated scaffolds. H1 hESCs on matrix-free PDL-treated fibrous scaffolds display similar behaviors to hESCs Matrigel-treated fibrous scaffolds, including extensive proliferation (A) and similar expression levels of pluripotency genes via qRT-PCR (no statistically significant differences, ANOVA; B) and transcription factor Oct4 via immunocytochemistry for 7 d (C) and 14 d (D) of undifferentiated culture. Scale bars = 50 μm. Graphs represent means ± sd. Statistical significance was evaluated by ANOVA with a Tukey HSD post hoc test.

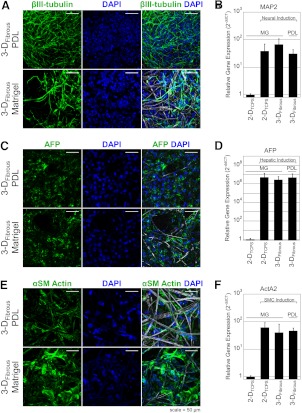

Following demonstration that hESCs remain undifferentiated in situ for up to 14 d, we investigated whether differentiation in situ could also be induced using soluble factors in the absence of exogenous ECM. By adapting previously described 2-D differentiation procedures to our 3-DFibrous scaffolds, we were able to successfully induce differentiation toward neuronal cells, hepatic-like cells, and SMCs, as demonstrated by confocal micrographs of βIII-tubulin, AFP, and αSM-actin expression (Fig. 6A, C, E) and elevated gene expression of Map2, AFP, and ActA2 (Fig. 6B, D, F) respectively. Images demonstrate extensive differentiation both on PDL- and Matrigel-treated 3-DFibrous scaffolds. In addition, qRT-PCR demonstrates significant up-regulation of differentiation markers in both PDL- and Matrigel-treated 3-DFibrous scaffolds for each lineage relative to undifferentiated controls. This demonstrates that directed differentiation to multiple lineages can be achieved in situ in the absence of exogenous ECM. In addition, differentiation to lineages of all three germ layers confirms the pluripotency of hESCs within these fibrous scaffolds.

Figure 6.

Fully synthetic PDL-treated 3-DFibrous fibrous scaffolds support directed differentiation of hESCs to multiple lineages, including neuronal cells, hepatic lineage cells, and SMCs. A, C, E) Confocal micrographs of βIII-tubulin (A), AFP (C), and αSM-actin (E) demonstrate in situ differentiation after 19 d of culture (7 d expansion, 12 d differentiation) in both PDL and Matrigel-treated 3-DFibrous scaffolds. B, D, F) Differentiation was evaluated quantitatively by qRT-PCR for Map2 (B), AFP (D), and ActA2 (F) for each lineage, demonstrating up-regulation of lineage markers for 2-DTCPS and both 3-DFibrous conditions relative to undifferentiated hESC controls. Graphs represent means ± sd.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the role of substrate topography on directed hESC self-renewal and differentiation. Our findings indicate that 3-D synthetic substrates exhibiting fibrous geometries are unique in terms of their support of the critical levels of adhesion and 3-D organization necessary for hESC survival, colony formation, and self-renewal. These effects appear to be in stark contrast to the hESC behaviors on 2-D and other 3-D, nonfibrous geometries. We report that the key mechanisms underlying hESC survival and colony formation in the fibrous substrates are cell organizational confinement and ECM matrix deposition.

The importance of the cell microenvironment in regulating stem cell differentiation has been well established (11, 39–41); however, the determinants of hESC adhesion and organization in 3-D synthetic substrates have yet to be elucidated. ECM ligand presentation and resultant cell-matrix interactions can vary significantly between 2-D substrates and substrates with various 3-D architectures (13, 41, 42). Scaffolds with nanofibrous or microfibrous architectures fabricated by electrospinning or other techniques are a versatile platform for stem cell culture and differentiation that have been extensively explored in recent years for their ability to mimic the topography of native ECM and influence cell behavior (43, 44), as recently reviewed by Lim and Mao (45), Cao et al. (46), and others. Electrospun scaffolds have been shown to support and enhance differentiation of hESCs to neurons (25, 47, 48) and osteoblasts (23), in addition to supporting undifferentiated culture of murine embryonic stem cells (mESCs; ref. 49) and feeder-based culture of hESCs (21). Our scaffold system consisting of PDL-treated synthetic microfibrous polymer scaffolds is distinguished from prior studies due to large fibers and porosities that allow for extensive infiltration and 3-D organization of hESCs in our 3-DFibrous condition, in contrast to most electrospun fibrous scaffolds that restrict cellular infiltration, as with our 2-DFibrous condition; the ability to support undifferentiated hESCs as well as in situ directed differentiation to multiple lineages within the same scaffold system; and the ability to support hESC survival, self-renewal, and differentiation in 3-D in the absence of exogenously incorporated ECM.

We fabricated fibrous scaffolds from synthetic, biodegradable polymers as model 3-D substrates for hESCs and screened a wide range of pretreatments used for cell culture to determine whether fibrous topography permits hESC survival and colony formation with pretreatments that do not support these behaviors in 2-D. Among the pretreatments tested, our most striking observation was that pretreatment with PDL, a synthetic polycation, supported extensive hESC survival and colony formation in 3-DFibrous substrates. This is in contrast to 2-DTCPS and 2-DFilm controls treated with PDL, which support initial hESC adhesion in the presence of the ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (32), but not colony formation and survival after Y-27632 is withdrawn. Thus, fully defined and synthetic 3-D substrates can support hESC colony formation in the absence of exogenous matrix cues.

Next, we sought to identify the key features of synthetic 3-D scaffolds requisite to support hESC colony formation and survival. We tested several parameters, including scaffold macroarchitecture (fibrous vs. nonfibrous geometries) and scaffold microarchitecture (fiber diameter) to define critical determinants necessary to support hESCs. We hypothesized that the 3-D organization provided by more cell-confining fibrous scaffolds would support increased cell-cell contacts and cell-matrix contacts compared to nonfibrous 3-D scaffolds, allowing enhanced survival and colony formation in the absence of exogenous ECM. Previous work with nonfibrous salt-leached scaffolds similar in geometry to our 3-DPorous conditions demonstrated that hESCs only attached to scaffolds treated with laminin, but not fibronectin or collagen (50). As expected, we found that PDL-treated 2-DTCPS, 2-DFilm, and nonfibrous 3-DPorous substrates do not support hESC adhesion, in contrast to controls treated with Matrigel. Further, we found that the synthetic PDL surface treatment of the polymer scaffolds promoted cell adhesion, but the underlying polymer composition of the fibrous scaffolds did not have unique effects in terms of dictating hESC colony formation. Additional studies of hESCs in PDL-treated fibrous scaffolds fabricated from poly(l-lactic acid) (PLLA; Supplemental Fig. S3A, B), a commercially available biodegradable polymer, revealed similar levels of colony formation and self-renewal marker expression to Matrigel-treated PLLA scaffolds (Supplemental Fig. S3C–E). In addition, fibrous scaffolds fabricated from a fast-degrading tyrosine-derived polycarbonate, poly(DTE-co-20%DT) (27), similarly supported hESC colony formation (data not shown), demonstrating that multiple members of our combinatorial library of tyrosine-derived polycarbonates are compatible with hESC cultures. This provides evidence that fibrous topography, rather than the polymer composition, is the key determinant of hESC colony formation in synthetic polymer substrates. Since both fibrous architectures tested supported hESC colony formation when treated with PDL, we chose to proceed with further studies into hESC self-renewal and differentiation with only our 3-DFibrous scaffold condition, due to enhanced cellular infiltration and 3-D organization within the scaffolds.

Despite the synthetic nature of fibrous scaffolds, we observed significant levels of matrix deposition from hESCs, which was hypothesized to be one of the key mechanisms for hESC long-term survival and self-renewal. hESCs in PDL-treated 3-DFibrous scaffolds deposited extensive amounts of laminin and collagen type I, along with modest amounts of collagen type IV. By contrast, hESCs in Matrigel-treated 3-DFibrous scaffolds demonstrated minimal production of any ECM proteins, suggesting that the initial hESC organization and substrate composition may influence the nature and location of the cell-deposited matrix. Several reports implicate specific ECM ligands in hESC adhesion and colony formation in 2-D (37, 38, 51). Thus, ECM production by hESCs, particularly of laminin, may be a major mechanism by which hESCs can be cultured in synthetically defined 3-DFibrous scaffolds in the absence of exogenous ECM. Laminin is the most prevalent component of Matrigel that also supports undifferentiated culture of hESCs on its own (51). In addition, characterization of hESCs in situ revealed that cells in both PDL and Matrigel-treated scaffolds highly express laminin-binding integrins α6 and β1, as demonstrated by immunocytochemistry. Thus, we further evaluated the importance of hESC binding to endogenously produced matrix within PDL-treated fibrous scaffolds by blocking adhesion to laminin using a functional blocking anti-laminin antibody. We found that functional blocking of laminin significantly reduced hESC adhesion to PDL-treated 3-DFibrous scaffolds, similar to Matrigel-treated controls. Since exogenous laminin is absent on PDL-treated substrates, the antibody-mediated inhibition of hESC adhesion suggests that both production and binding of hESCs to laminin is a key regulator of hESC adhesion and survival in the absence of exogenous ECM treatments.

After verifying the localization of the cell deposited ECM-based matrix in proximity to hESC colonies, we examined whether this matrix was sufficient to support hESC proliferation, self-renewal, and directed differentiation in the absence of exogenous ECM. We found that hESCs in PDL-treated fibrous scaffolds proliferated extensively and maintained an undifferentiated phenotype for 14 d based on immunocytochemistry against pluripotency markers Oct4, SSEA-4, and Tra-1-60, and gene expression of POU5F1, NANOG, and TERT, all of which are highly expressed in undifferentiated cells. This was observed for multiple hESC cell lines (H1 and H9) cultured under feeder-free conditions, with all markers being expressed to a similar degree to hESCs on Matrigel-treated 2-DTCPS or 3-DFibrous scaffolds. This suggests that the combination of PDL-treated synthetic scaffolds and hESC-remodeled matrix represent a sufficient niche to support self-renewal.

Finally, we tested whether directed differentiation of hESCs to multiple lineages could be achieved in situ using soluble inducing factors based on previously published reports for 2-D adherent differentiation to neuronal cells (33, 34), hepatic-lineage cells (35), and SMCs (36). We successfully generated βIII-tubulin+ neuronal cells, AFP+ hepatic lineage cells, and αSM-actin+ SMCs in situ, as verified by immunocytochemistry. In addition, differentiation was further confirmed using qRT-PCR. As expected, we observed slight differences in the effectiveness of in situ differentiation between Matrigel-treated 2-DTCPS, Matrigel-treated 3-DFibrous, and PDL-treated 3-DFibrous substrates for each target lineage. While we confirmed extensive differentiation relative to 2-DTCPS undifferentiated controls, additional studies and optimization would be required to maximize differentiation toward each lineage and effectively compare differentiation efficiencies on each substrate condition. A caveat of the current scaffold designs is that cells cannot be easily harvested from thick fibrous mats for repeated expansion, a limitation that could be overcome in the future through the use of scaffolds based on rapidly degrading members of the tyrosine-derived polycarbonate library (27, 52) or thinner mats of fibers that restrict the extensive cellular infiltration we observe in our 3-DFibrous scaffolds. In summary, we report that exogenous ECM is not necessary for induction of differentiation within 3-DFibrous scaffolds, indicating that this may be a promising platform for generating differentiated cells for in situ study or in vivo transplantation for potential regenerative medicine applications.

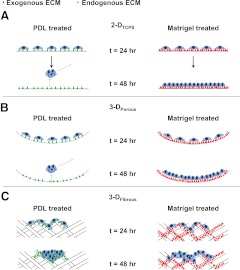

Based on our results demonstrating that fully synthetic 3-D microenvironments can support hESCs, we offer a conceptual model underlying hESC adhesion, survival, and colony formation within these synthetic 3-D microenvironments (Fig. 7). Our results suggest that cell-confining fibrous substrate geometry influences hESC survival based on two key mediators: deposition of ECM and reestablishment of proximal cell-cell contacts and multicellular organization following seeding as single cells. Within 3-D fibrous substrates (Fig. 7C), enhanced local surface area relative to 2-DTCPS and 3-DPorous substrates (Fig. 7A, B) allows aggregation of hESCs during seeding and greater surface area for matrix deposition, which allows hESCs to reestablish cell-cell contacts while providing sufficient accumulation of endogenously produced matrix to generate viable and adherent undifferentiated hESC colonies. Immunostaining for cell-cell adhesion protein E-cadherin reveals extensive establishment of cell-cell contacts within hESC colonies on both PDL- and Matrigel-treated 2-DFibrous and 3-DFibrous substrates, with tighter cell-cell contacts and less colony spreading observed in PDL-treated substrates (Supplemental Fig. S4). This mechanism supports the premise that hESCs may be cultured in synthetic substrates lacking exogenous ECM as long as appropriate scale and fibrous nature of geometric features are present. Such substrates can serve as an effective framework for future design of synthetic scaffolds for developmental biology studies of hESC behaviors in situ or for hESC expansion and differentiation relevant for drug discovery or clinical applications.

Figure 7.

Conceptual model of hESC colony formation on 3-DFibrous scaffolds in the absence of exogenous ECM. A, B) On planar 2-DTCPS (A) and nonfibrous 3-DPorous substrates (B), hESCs aggregate on Matrigel-treated surfaces, since the surface possess sufficient ECM (exogenous ECM, red triangles) to promote hESC adhesion and migration to reform cell-cell contacts after removal of ROCK-inhibitor Y-27632. On PDL-treated substrates that lack exogenous ECM, hESCs produce ECM (endogenous ECM, green) and establish proximal cell-cell contacts in place of forming extensive cell-matrix contacts and colony spreading. This results in the formation of tight aggregates of cells with weak cell-surface adhesion, which easily detach from the surface. C) In contrast, the fibrous 2-DFibrous and 3-DFibrous scaffolds support enhanced cell aggregation during seeding and enhanced surface area for ECM deposition, allowing hESCs to form both cell-cell and cell-matrix contacts in the absence of exogenous ECM, thus allowing colony formation and self-renewal.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we discovered that fibrous architecture of synthetic polymer scaffolds combined with PDL allows hESCs to engineer a self-contained microenvironment that supports their proliferation, self-renewal, and differentiation in combination with soluble cues. This opens up possibilities for design of 3-D biomaterials for hESC growth or differentiation with appropriate architectures and geometric features that bypass the need for incorporation of matrix proteins or feeder cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the New Jersey Commission on Science and Technology Stem Cell Core grant (principal investigators P.V.M. and M.G.), U.S. National Institutes of Health grant EB000146 (RESBIO: Integrated Resource for Polymeric Materials; principal investigators P.V.M. and J.K.), New Jersey Commission on Spinal Cord Research exploratory grant 10-3090-SCR-E-0 (principal investigator P.V.M.), and National Science Foundation Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship grant 0801620 (Stem Cell Science and Engineering; principal investigator P.V.M.).

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- 2-D

- 2-dimensional

- 2-DFibrous

- 2-dimensional fibrous pDTEc

- 2-DFilm

- 2-dimensional pDTEc film

- 2-DTCPS

- 2-dimensional tissue culture polystyrene

- 3-DFibrous

- 3-dimensional fibrous pDTEc

- 3-DPorous

- macroporous pDTEc

- αSM-actin

- α-smooth muscle actin

- ActA2

- α-smooth muscle actin

- AFP

- α-fetoprotein

- DAPI

- 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DCM

- dichloromethane

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- hESC

- human embryonic stem cell

- HFIP

- 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol

- mESC

- murine embryonic stem cell

- NEAA

- nonessential amino acid

- Oct4

- octamer-binding transcription factor 4

- PDL

- poly-d-lysine

- pDTEc

- poly(desaminotyrosyl tyrosine ethyl ester carbonate)

- PLL

- poly-l-lysine

- PLLA

- poly(l-lactic acid)

- PLO

- poly-l-ornithine

- POU5F1

- POU domain, class 5, transcription factor 1

- SEM

- scanning electron microscope

- SMC

- smooth muscle cell

- SSEA-4

- stage-specific embryonic antigen 4

- TERT

- telomerase reverse transcriptase

- Tra-1-60

- tumor rejection antigen 1-60

REFERENCES

- 1. Thomson J. A., Itskovitz-Eldor J., Shapiro S. S., Waknitz M. A., Swiergiel J. J., Marshall V. S., Jones J. M. (1998) Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science 282, 1145–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reubinoff B. E., Pera M. F., Fong C.-Y., Trounson A., Bongso A. (2000) Embryonic stem cell lines from human blastocysts: somatic differentiation in vitro. Nat. Biotech. 18, 399–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ariff Bongso C.-Y. F., Gauthaman Kalamegam, (2008) Taking stem cells to the clinic: major challenges. J. Cell. Biochem. 105, 1352–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McDevitt T. C., Palecek S. P. (2008) Innovation in the culture and derivation of pluripotent human stem cells. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 19, 527–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yao S., Chen S., Clark J., Hao E., Beattie G. M., Hayek A., Ding S. (2006) Long-term self-renewal and directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells in chemically defined conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 6907–6912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ludwig T. E., Levenstein M. E., Jones J. M., Berggren W. T., Mitchen E. R., Frane J. L., Crandall L. J., Daigh C. A., Conard K. R., Piekarczyk M. S., Llanas R. A., Thomson J. A. (2006) Derivation of human embryonic stem cells in defined conditions. Nat. Biotech. 24, 185–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brafman D. A., Chang C. W., Fernandez A., Willert K., Varghese S., Chien S. (2010) Long-term human pluripotent stem cell self-renewal on synthetic polymer surfaces. Biomaterials 31, 9135–9144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Villa-Diaz L. G., Nandivada H., Ding J., Nogueira-de-Souza N. C., Krebsbach P. H., O'Shea K. S., Lahann J., Smith G. D. (2010) Synthetic polymer coatings for long-term growth of human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotech. 28, 581–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Melkoumian Z., Weber J. L., Weber D. M., Fadeev A. G., Zhou Y., Dolley-Sonneville P., Yang J., Qiu L., Priest C. A., Shogbon C., Martin A. W., Nelson J., West P., Beltzer J. P., Pal S., Brandenberger R. (2010) Synthetic peptide-acrylate surfaces for long-term self-renewal and cardiomyocyte differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotech. 28, 606–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Watt F. M., Hogan B. L. M. (2000) Out of Eden: stem cells and their niches. Science 287, 1427–1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burdick J. A., Vunjak-Novakovic G. (2008) Engineered microenvironments for controlled stem cell differentiation. Tissue Eng. A 15, 205–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee J., Cuddihy M. J., Kotov N. A. (2008) Three-dimensional cell culture matrices: state of the art. Tissue Eng. B 14, 61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Berrier A. L., Yamada K. M. (2007) Cell–matrix adhesion. J. Cell. Physiol. 213, 565–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Doyle A. D., Wang F. W., Matsumoto K., Yamada K. M. (2009) One-dimensional topography underlies three-dimensional fibrillar cell migration. J. Cell Biol. 184, 481–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ranucci C. S., Kumar A., Batra S. P., Moghe P. V. (2000) Control of hepatocyte function on collagen foams: sizing matrix pores toward selective induction of 2-D and 3-D cellular morphogenesis. Biomaterials 21, 783–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu H., Lin J., Roy K. (2006) Effect of 3D scaffold and dynamic culture condition on the global gene expression profile of mouse embryonic stem cells. Biomaterials 27, 5978–5989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levenberg S., Huang N. F., Lavik E., Rogers A. B., Itskovitz-Eldor J., Langer R. (2003) Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells on three-dimensional polymer scaffolds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 12741–12746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bahney C. S., Hsu C.-W., Yoo J. U., West J. L., Johnstone B. (2011) A bioresponsive hydrogel tuned to chondrogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells. FASEB J. 25, 1486–1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gerecht S., Burdick J. A., Ferreira L. S., Townsend S. A., Langer R., Vunjak-Novakovic G. (2007) Hyaluronic acid hydrogel for controlled self-renewal and differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 11298–11303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li Z., Leung M., Hopper R., Ellenbogen R., Zhang M. (2010) Feeder-free self-renewal of human embryonic stem cells in 3D porous natural polymer scaffolds. Biomaterials 31, 404–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gauthaman K., Venugopal J. R., Yee F. C., Peh G. S. L., Ramakrishna S., Bongso A. (2009) Nanofibrous substrates support colony formation and maintain stemness of human embryonic stem cells. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 13, 3475–3484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ferreira L. S., Gerecht S., Fuller J., Shieh H. F., Vunjak-Novakovic G., Langer R. (2007) Bioactive hydrogel scaffolds for controllable vascular differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Biomaterials 28, 2706–2717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith L. A., Liu X., Hu J., Ma P. X. (2010) The enhancement of human embryonic stem cell osteogenic differentiation with nano-fibrous scaffolding. Biomaterials 31, 5526–5535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yang F., Cho S.-W., Son S. M., Hudson S. P., Bogatyrev S., Keung L., Kohane D. S., Langer R., Anderson D. G. (2010) Combinatorial extracellular matrices for human embryonic stem cell differentiation in 3D. Biomacromolecules 11, 1909–1914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shahbazi E., Kiani S., Gourabi H., Baharvand H. (2011) Electrospun nanofibrillar surfaces promote neuronal differentiation and function from human embryonic stem cells. Tissue Eng. A 17, 3021–3031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ertel S. I., Kohn J. (1994) Evaluation of a series of tyrosine-derived polycarbonates as degradable biomaterials. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 28, 919–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Meechaisue C., Dubin R., Supaphol P., Hoven V. P., Kohn J. (2006) Electrospun mat of tyrosine-derived polycarbonate fibers for potential use as tissue scaffolding material. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 17, 1039–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Treiser M. D., Yang E. H., Gordonov S., Cohen D. M., Androulakis I. P., Kohn J., Chen C. S., Moghe P. V. (2009) Cytoskeleton-based forecasting of stem cell lineage fates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 610–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu E., Treiser M. D., Johnson P. A., Patel P., Rege A., Kohn J., Moghe P. V. (2007) Quantitative biorelevant profiling of material microstructure within 3D porous scaffolds via multiphoton fluorescence microscopy. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 82B, 284–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ludwig T. E., Bergendahl V., Levenstein M. E., Yu J., Probasco M. D., Thomson J. A. (2006) Feeder-independent culture of human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Meth. 3, 637–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bajpai R., Lesperance J., Kim M., Terskikh A. V. (2008) Efficient propagation of single cells accutase-dissociated human embryonic stem cells. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 75, 818–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Watanabe K., Ueno M., Kamiya D., Nishiyama A., Matsumura M., Wataya T., Takahashi J. B., Nishikawa S., Nishikawa S., Muguruma K., Sasai Y. (2007) A ROCK inhibitor permits survival of dissociated human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotech. 25, 681–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nat R., Nilbratt M., Narkilahti S., Winblad B., Hovatta O., Nordberg A. (2007) Neurogenic neuroepithelial and radial glial cells generated from six human embryonic stem cell lines in serum-free suspension and adherent cultures. Glia 55, 385–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hu B.-Y., Zhang S.-C. (2010) Directed differentiation of neural-stem cells and subtype-specific neurons from hESCs. In Cellular Programming and Reprogramming Vol. 636, pp. 123–137, Humana Press, New York: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen Y.-F., Tseng C.-Y., Wang H.-W., Kuo H.-C., Yang V. W., Lee O. K. (2011) Rapid generation of mature hepatocyte-like cells from human induced pluripotent stem cells by an efficient three-step protocol. Hepatology 55, 1193–1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Huang H., Zhao X., Chen L., Xu C., Yao X., Lu Y., Dai L., Zhang M. (2006) Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into smooth muscle cells in adherent monolayer culture. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 351, 321–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meng Y., Eshghi S., Li Y. J., Schmidt R., Schaffer D. V., Healy K. E. (2010) Characterization of integrin engagement during defined human embryonic stem cell culture. FASEB J. 24, 1056–1065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Braam S. R., Zeinstra L., Litjens S., Ward-van Oostwaard D., van den Brink S., van Laake L., Lebrin F., Kats P., Hochstenbach R., Passier R., Sonnenberg A., Mummery C. L. (2008) Recombinant vitronectin is a functionally defined substrate that supports human embryonic stem cell self-renewal via αVβ5 integrin. Stem Cells 26, 2257–2265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sands R. W., Mooney D. J. (2007) Polymers to direct cell fate by controlling the microenvironment. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 18, 448–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dawson E., Mapili G., Erickson K., Taqvi S., Roy K. (2008) Biomaterials for stem cell differentiation. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 60, 215–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stevens M. M., George J. H. (2005) Exploring and engineering the cell surface interface. Science 310, 1135–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cukierman E., Pankov R., Stevens D. R., Yamada K. M. (2001) Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension. Science 294, 1708–1712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lim S. H., Liu X. Y., Song H., Yarema K. J., Mao H.-Q. (2010) The effect of nanofiber-guided cell alignment on the preferential differentiation of neural stem cells. Biomaterials 31, 9031–9039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tai B. C. U., Wan A. C. A., Ying J. Y. (2010) Modified polyelectrolyte complex fibrous scaffold as a matrix for 3D cell culture. Biomaterials 31, 5927–5935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lim S. H., Mao H.-Q. (2009) Electrospun scaffolds for stem cell engineering. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 61, 1084–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cao H., Liu T., Chew S. Y. (2009) The application of nanofibrous scaffolds in neural tissue engineering. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 61, 1055–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Carlberg B., Axell M. Z., Nannmark U., Liu J., Kuhn H. G. (2009) Electrospun polyurethane scaffolds for proliferation and neuronal differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Biomed. Mater. 4, 045004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mahairaki V., Lim S. H., Christopherson G. T., Xu L., Nasonkin I., Yu C., Mao H.-Q., Koliatsos V. E. (2011) Nanofiber matrices promote the neuronal differentiation of human embryonic stem cell derived-neural precursors in vitro. Tissue Eng. A. 17, 855–863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ouyang A., Ng R., Yang S. T. (2007) Long-term culturing of undifferentiated embryonic stem cells in conditioned media and three-dimensional fibrous matrices without extracellular matrix coating. Stem Cells 25, 447–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gao S. Y., Lees J. G., Wong J. C. Y., Croll T. I., George P., Cooper-White J. J., Tuch B. E. (2010) Modeling the adhesion of human embryonic stem cells to poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) surfaces in a 3D environment. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 92A, 683–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Miyazaki T., Futaki S., Hasegawa K., Kawasaki M., Sanzen N., Hayashi M., Kawase E., Sekiguchi K., Nakatsuji N., Suemori H. (2008) Recombinant human laminin isoforms can support the undifferentiated growth of human embryonic stem cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 375, 27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bourke S. L., Kohn J. (2003) Polymers derived from the amino acid -tyrosine: polycarbonates, polyarylates and copolymers with poly(ethylene glycol). Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 55, 447–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.