Abstract

Blood vessels are formed during development and tissue repair through a plethora of modifiers that coordinate efficient vessel assembly in various cellular settings. Here we used the yeast 2-hybrid approach and demonstrated a broad affinity of connective tissue growth factor (CCN2/CTGF) to C-terminal cystine knot motifs present in key angiogenic regulators Slit3, von Willebrand factor, platelet-derived growth factor-B, and VEGF-A. Biochemical characterization and histological analysis showed close association of CCN2/CTGF with these regulators in murine angiogenesis models: normal retinal development, oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR), and Lewis lung carcinomas. CCN2/CTGF and Slit3 proteins worked in concert to promote in vitro angiogenesis and downstream Cdc42 activation. A fragment corresponding to the first three modules of CCN2/CTGF retained this broad binding ability and gained a dominant-negative function. Intravitreal injection of this mutant caused a significant reduction in vascular obliteration and retinal neovascularization vs. saline injection in the OIR model. Knocking down CCN2/CTGF expression by short-hairpin RNA or ectopic expression of this mutant greatly decreased tumorigenesis and angiogenesis. These results provided mechanistic insight into the angiogenic action of CCN2/CTGF and demonstrated the therapeutic potential of dominant-negative CCN2/CTGF mutants for antiangiogenesis.—Pi, L., Shenoy, A. K., Liu, J., Kim, S., Nelson, N., Xia, H., Hauswirth, W. W., Petersen, B. E., Schultz, G. S., Scott, E. W. CCN2/CTGF regulates neovessel formation via targeting structurally conserved cystine knot motifs in multiple angiogenic regulators.

Keywords: retinal neovascularization, tumorigenesis, oxygen-induced retinopathy

Blood vessels are formed through coordinated actions mediated by pro- and antiangiogenic factors during development and wound healing. In disease states, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) may mediate adaptive transcriptional responses and activate proangiogenic factors, such as VEGF-A, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-B, and TGF-β (1). A persistent imbalance between anti- and proangiogenic factors causes aberrant neovascularization as the common pathway to blindness in ocular diseases and contributes to pathogenesis of very deadly conditions, including cancer progression. Antiangiogenic therapy targeted to key angiogenic factors has been used for many clinical treatments (2). Comprehensive understanding of the fundamental process of neovessel growth is necessary for developing effective therapeutic strategies against pathological angiogenesis.

ECM has been known to carry structural and signaling entities required for any tissue repair and vascular remodeling. The cysteine-rich 61/connective tissue growth factor (CTGF)/nephroblastoma (CCN) protein family represents a novel class of extracellular signaling modulators that coordinate a diverse variety of biological processes, including cardiovascular and skeletal development during embryogenesis, as well as inflammation, wound healing, and tissue repair in adulthood (3). CCN proteins share mosaic tandem modular structures and elicit cell-specific responses through binding of many ECM proteins, cell surface proteins, and growth factors. We have found that CTGF, also termed CCN2, acts as a proadhesive molecule situated in the provisional matrix of regenerating livers and promotes cell adhesion and migration by linking cells and ECM through binding of integrin and fibronectin (4). CCN2/CTGF is highly up-regulated during tissue repair, but abnormal amplification of CCN2/CTGF-dependent signals results in regeneration failure and scar formation in various kinds of fibrotic disorders (5, 6).

CCN2/CTGF was originally identified from conditioned medium of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in 1991 (7), but its function in blood vessel formation, a critical event during tissue repair, has not been fully understood. CCN2/CTGF seems to be a potent angiogenic inducer, at least partly through engagement of integrins, in the mouse models of corneal angiogenesis and tumorigenesis (8, 9), although this molecule is able to interact with VEGF-A and prevents VEGF-A/receptor recognition, leading to decreased VEGF signaling for antiangiogenesis (10). CCN2/CTGF-knockout mice display impaired angiogenesis in bone growth plates (11). Recently, we demonstrated that CCN2/CTGF is specifically expressed in retinal vascular beds and plays an important role for vessel growth during early retinal development. Intravitreal injection of excessive CCN2/CTGF protein promotes the fibrovascular reaction in murine retinal ischemia after laser injury (12). In an effort to understand the molecular mechanism underlying CCN2/CTGF action, here we attempted to identify its signal partners using yeast 2-hybrid cDNA analysis. The functional relationship between CCN2/CTGF and its binding candidates was further characterized in mouse angiogenesis models during normal retinal development, oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR), and Lewis lung carcinomas (LLCs). We asked whether disruption of CCN2/CTGF binding to its signal partners by a mutant with the first three modules (CCN2/CTGFI–III) could affect the pathological angiogenesis in ischemic retinas and hypoxic LLC tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast 2-hybrid analysis

The cDNA library screening and yeast 2-hybrid analyses were described previously (4). The C-terminal cystine knot (CT) motifs were fused with the DNA binding domain (BD) of GAL4 in pPC97 vector. Full-length rat CCN2/CTGF cDNA and its deletion mutants were fused with the GAL4 activation domain (AD) in pPC86 vector. Primer sets for DNA amplification of all plasmids in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used for PCR amplification and plasmid production

| Plasmid name | Vector | Primer name | Primer sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| AD:CCN2/CTGF | pPC86 | P0 | 5′-gtcgacGCCTGCCACCGGCCAGGACT-3′ |

| P4 | 5′-gcggccgcCTTACGCCATGTCTCCATACATCTTCCTGT-3′ | ||

| AD:CCN2/CTGFI | pPC86 | P0 and P1 | 5′-gcggccgcTTAACACGGACCCACCGAAGACACA-3′ |

| AD:CCN2/CTGFI,II | pPC86 | P0 and P2 | 5′-gcggccgcTTAGTGTCTTCCAGTGGTAGGCAG-3′ |

| AD:CCN2/CTGFI-III | pPC86 | P0 and P3 | 5′-gcggccgcTTACCTCTAGGTCAGGCTTCACAGGG-3′ |

| AD:CCN2/CTGFII-IV | pPC86 | P5 and P4 | 5′-gtcgacaTGTGTCTTCGGTGGGTCCGTGTACCG-3′ |

| AD:CCN2/CTGFIII,IV | pPC86 | P6 and P4 | 5′-gtcgacaGTCGACTGCCTACCGACTGGAAGACACATTTGG-3′ |

| AD:CCN2/CTGFIV | pPC86 | P7 and P4 | 5′-gtcgacACCCTGTGAAGCTGACCTAGAGGAAAACA-3′ |

| AD:CCN2/CTGFII | pPC86 | P5 and P2 | |

| AD:CCN2/CTGFIII | pPC86 | P6 and P2 | |

| AD:CCN2/CTGFII,III | pPC86 | P5 and P3 | |

| CCN2/CTGFI:3xFLAG | pIRES2 | P8 | 5′-ctcggatccGACCATGCTCGCCTCCGTCG-3′ |

| P9 | 5′-tagtcgacGACGGACCCACCGAAGACACA-3′ | ||

| CCN2/CTGFI,II:3xFLAG | pIRES2 | P8 and P10 | 5′-tagtcgacGTCTTCCAGTCGGTAGGCAG-3′ |

| CCN2/CTGFI–III:3xFLAG | pIRES2 | P8 and P11 | 5′-tagtcgacCTCTAGGTCAGCTTCACAGGG-3′ |

| CTGF:3xFLAG | pIRES2 | P8 and P12 | 5′-tagtcgacCGCCATGTCTCCATACATCTTCCT-3′ |

| BD:Slit3-CT | pPC97 | P13 | 5′-aaggtcgacCGAGCCCTACTGCCTGTGCCAG-3′ |

| P14 | 5′-tagcggccgcAGGAACACGCGAGGCAGCCGCA-3′ | ||

| BD:vWF-CT | pPC97 | P15 | 5′-gaggtcgacCTTCGATGAACGCAAGTGTCTGGCT-3′ |

| P16 | 5′-tagcggccgcTTGCCACAATTACGGGGAGAACA-3′ | ||

| BD:CCN2/CTGF-CT | pPC97 | P7 and P4 | |

| BD:PDGF-B-CT | pPC97 | P17 | 5′-gaggtcgacCTTGGCTCGTGGAAGAAGGAGCCT-3′ |

| P18 | 5′-tagcggccgcGGGTCACAGGCCGTGCAGC-3′ | ||

| BD:VEGF-A-CT | pPC97 | P19 | 5′-aggtcgacCCAGGCTGCACCCACGACAG-3′ |

| P20 | 5′-tagcggccgcTTACCGCCTTGGCTTGTCACATCT-3′ | ||

| MBP:Slit3-CT | pMAL | P13 and P14 | |

| MBP:vWF-CT | pMAL | P15 and P16 | |

| MBP:CCN2/CTGF-CT | pMAL | P7 and P4 |

Primer ends carrying restriction enzyme sites are shown in lowercase.

Protein expression, purification, and immunoprecipitation

The cDNA fragments corresponding to the rat CCN2/CTGF and its mutants were inserted at SalI and NotI sites of a modified pIRE2-GFP vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). 3xFLAG epitope was added before the stop codon of each protein. For the generation of CCN2/CTGF:myc, the full-length cDNA from the pIRE2 plasmid was in-frame fused to the 5′ myc epitope sequence at BamHI and SalI restriction enzyme sites in pCMV-Tag 5A vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). Murine VEGF-A with myc epitope on a pcDNA3 vector was a gift from Dr. Jason Butler (Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA). Human PDGF-B in pCMV-SPORT6 vector was from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL, USA). Human Slit3 cDNA was derived from a plasmid from Kazusa DNA Reseach Institute (Kisarazu, Japan) and inserted into KpnI and XhoI sites of pEF6/V5-His-Topo vector (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA). In immunoprecipitation assays, conditioned media from CHO cells expressing VEGF-A, PDGF-B, Slit3:V5, 3xFLAG-tagged CCN2/CTGF, or its deletion mutants were adjusted to contain 1× Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and 150 mM NaCl). Total LLC tumor homogenates were also extracted using TBS buffer supplemented with 0.5% Triton-100 and proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and 50–100 μl of M2 antibody-conjugated agarose (Sigma-Aldrich) was incubated with conditioned medium or LLC tumor protein lysates. Immunocomplexes were washed in TBS buffer, eluted in 0.1 M glycine (pH 3.5), boiled in the Laemmli sample buffer, resolved in SDS-PAGE gels, and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. In addition, a mouse monoclonal myc antibody clone 9E10 and protein A/G beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) were used to immunoprecipitate myc-tagged CCN2/CTGF from LLC cell lines in a similar way except for additional chemical cross-linking with 2 mM dithiobis(succinimidyl) propionate (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) before cell lysis. RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1.0% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0) was used for total protein extraction and washing. Immunocomplexes were resolved in SDS-PAGE gels under reducing conditions. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated myc antibody (Invitrogen), HRP-conjugated V5 antibody (Invitrogen), rabbit PDGF-B antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), rabbit Slit3 antibody (Abcam), HRP-conjugated M2 antibody (Sigma), and HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) were used as primary and secondary antibodies, respectively, during immunoblotting.

Purification of 3xFLAG-tagged CCN2/CTGF and mutants using M2 conjugated agarose from conditioned CHO cell medium was reported previously (4).

For purification of Slit3 protein, the 293FT-Slit3V5-6xHis/dsRed cell line that stably expressed a high level of this protein was generated using a lentiviral delivery system as follows. A lentiviral construct was generated by cloning Slit3 cDNA and V5-6xHis sequence into XhoI and PmeI sites of pLVX-Puro vector (Clontech). The IRES-dsRed sequence was coexpressed in the construct to facilitate visualization. The resulting plasmid containing a lentiviral backbone (0.7 μl) was cotransfected into 293FT cells with 0.7 μg of enveloping plasmid pMD2.G and 0.7 μg of packaging plasmid psPAX2 containing a gag/pol sequence. Stable 293FT cell lines were established after 3-wk selection in DMEM with 10% FBS and 5 μg/ml puromycin. The 293FT-Slit3V5-6xHis/dsRed cell line was identified based on bright red fluorescence observed under a microscope and the high level of Slit3 protein detected in Western blot analysis. In a large-scale preparation, 1 × 1010 293FT-Slit3V5-6xHis/dsRed cells grown in T225 flasks were incubated with a high salt solution containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 1 M NaCl, and protease inhibitor cocktail. Solubilized proteins in supernatant were concentrated in Amicon Ultra-15 centricons with a 100-kDa cutoff (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and equilibrated with binding buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4 and 300 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) containing 20 mM imidazole before binding on a His60 nickel gravity column (Clontech); 50 and 250 mM imidazole in binding buffer was used for washing and elution, respectively. The quality of the purified protein was verified by silver staining using a SilverQuest staining kit (Invitrogen).

For preparation of maltose-binding protein (MBP) fusion proteins, the CT motifs tested were inserted at SalI and NotI sites before the 3′ of MBP in a modified pMAL vector. Fusion proteins were induced in Escherichia coli DE3 strain with 0.4 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, purified using amylose beads (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) with column buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 200 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA, and eluted with 10 mM maltose. In pull-down assays, the mixtures of 5 μg of MBP fusion CT motifs, 3xFLAG-tagged CCN2/CTGF, or mutant proteins in TBS buffer were incubated with 50 μl of M2-conjugated agarose. Bound proteins were washed and prepared for Western blotting analysis similar to the immunoprecipitation assay mentioned above except that HRP-conjugated MBP antibody (New England Biolabs) was used for immunodetection.

Solid-phase protein-binding assay

Solid-phase protein-binding assays were described previously (4) with the following modification. Microplates were coated with purified 3xFLAG-tagged CCN2/CTGF protein, blocked with TBS-T (TBS with 0.05% Tween 20 and 1% BSA) buffer, and incubated with mixtures of purified V5-6xHis-tagged Slit3 protein with or without purified 3xFLAG-tagged CCN2/CTGFI–III protein. Unbound protein was removed by extensive washing with TBS-T. Bound Slit3 protein was detected with V5 antibody-conjugated HRP (Invitrogen) and tetramethylbenzidine as the substrate (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) followed by reading of the optical density at 450 nm by an automated microplate reader.

Tube formation assay

HUVECs were cultured in Medium 200 with growth factor supplement (Invitrogen), and 2 × 104 serum-starved cells in 100 μl of plain medium containing the tested proteins were inoculated into 96-well growth factor-reduced Matrigel plates (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Tube formation was photographed by a phase-contrast microscope at ×10 view at 6 h after seeding. Total tube length was quantified with ImageJ software (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Cell division cycle 42 GTP-binding protein (Cdc42)-GTPase assay

HUVECs were grown to 95% confluence on 10-cm plates and stimulated with the tested proteins for 20 min, followed by washing with PBS and extracting in lysis buffer (125 mM HEPES, pH 7.5; 750 mM NaCl; 5% Nonidet P-40; 50 mM MgCl2; 5 mM EDTA; and 10% glycerol). Active Cdc42 in total cell lysates was pulled down based on its binding to the p21-binding domain of p21-activated protein kinase in a form of a glutathione S-transferase fusion and detected with mouse monoclonal Cdc42 antibody in a GTPase assay kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA, USA).

OIR murine model and intravitreal injections of recombinant CCN2/CTGFI–III protein

All animal protocols were approved by the University of Florida Animal Care and Usage Committee. CCN2/CTGFp-EGFP [stock Tg(CCN2/CTGF-EGFP)156Gsat] transgenic mice on a C57BL/6 genetic background were generated as described previously (12). OIR was induced in neonatal mice according to an established protocol (13). Postnatal day (P) 7 mouse pups with nursing dams were exposed to 75 ± 2% oxygen for 5 d in a sealed incubator. The pups at P12 were returned to normoxia. Immediately after returning to room air, right eyes of the mice were injected intravitreally with 2 μg of recombinant CCN2/CTGFI–III protein diluted in 0.5 μl of PBS. Left eyes in the same animals were injected with an equal volume of PBS as controls. Repeat injections were done at P14 through a previously unmanipulated section of the limbus. Animals were sacrificed at P17 with a lethal dose of 0.6 mg/g Avertin (Sigma-Aldrich). Fixed eyes were stained with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated Griffonia simplicifolia isolectin IB4 (GSI; Invitrogen) for vascular endothelium before retinal flat-mounting. Confocal images were taken at ×5 view. Computer-aided quantification of retinal neovascularization and obliteration was performed according to the published method using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA; ref. 14). In brief, avascular zones and total retinal areas in the central retina were delineated. Vascular obliteration was calculated as a percentage of the total retinal area. Neovascular tufts were also selected based on their tortuous morphology and strong GSI staining. All selected neovascular areas were summed and divided by the total retinal area. Neovascularization was expressed as a percentage of total retinal area.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNAs were extracted from retinas of normal and oxygen-treated neonates in the OIR model at desired time points using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Quantitative RT-PCR analyses of the CCN2/CTGF gene and semiquantitative RT-PCR analyses of Slit3, Rounabout 1 (Robo1), Robo4, and Actin genes were performed under the same conditions as described previously (12) except for the following primer sets: Slit3, 5′-GCGGCGGATGGCTTCACGGACTAT-3′ and 5′-ACGAGGTGCGCATCAACAACGAG-3′; Robo1, 5′-CCACTTTCAGGCCCGCATACTCC-3′ and 5′-ACATGCCCCACCCACCAGACA-3′; and Robo4, 5′-CCGTCACTAGGCTTCTGGAG-3′ and 5′-TGGTTGTGGAGAGTCTGCTG-3′.

Hypoxia treatment and Western blot analysis for HIF-1α

LLC cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS. Cells were harvested for RNA and protein extraction after a 12-h exposure in a hypoxia chamber (BD Biosciences). Total proteins were extracted in RIPA buffer with proteinase inhibitors and resolved in 8% SDS-PAGE gels. A mouse HIF-1α antibody (BD Biosciences), mouse actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), and HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG were used for Western blot analysis.

Murine LLC model and production of recombinant adenovirus and lentivirus to alter CCN2/CTGF function

For knocking down CCN2/CTGF expression in LLC cells, 21 nucleotide sequences were chosen from rat CCN2/CTGF cDNA (GenBank accession no. AB023068.1) and designed for short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) using small interfering RNA Wizard software (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA). shRNAs of CCN2/CTGF sequence 1 (shCTGF1; 5′-AAGACCTGTGCCTGCCATTACAACTCTTGATTGTAATGGCAGGCACAGGTGAGGT-3′), CCN2/CTGF sequence 2 (shCTGF2; 5′-AAAGAGTGGAGCGCCTGTTCTAACTCTTGATTAGAACAGGCGCTCCACTCTGAG-3′), and scramble shRNA sequence (5′-AAGCATATGTGCGTACCTAGCATCTCTTGAATGCTAGGTACGCACATATGCGAGGT-3′) were cloned to the 3′ end of the H1 promoter in psiRNA-hH1GFPzeo vector (InvivoGen). The H1 promoter and shRNA regions were cloned into the PacI site of the pAdEasy-1 adenoviral vector and expressed in AD293 cells (Stratagene). Titers of 1.7 × 1011 plaque forming units (PFU)/ml were achieved after ultracentrifugation on a CsCl gradient. For the assessment of knockdown efficiency, LLC cells were infected with the recombinant viruses in 10 multiplicity of infection. Two days later, infected cells were cultured in the hypoxic chamber for 12 h. Total protein lysates in RIPA buffer were extracted from hypoxic LLC cells and subjected to Western blot analysis using a rabbit CCN2/CTGF antibody (Abcam) and the mouse actin antibody as a loading control. In tumor growth assays, 2 × 106 LLC cells were subcutaneously implanted into 6- to 8-wk-old mice, and 1 × 109 PFU of recombinant shCTGF1 or scramble adenovirus was injected into palpable LLC tumors (∼20 mm3) twice at 3 and 4 d postimplantation. Tumor volumes were determined by measuring tumor sizes with calipers and were calculated using the formula (mm3) = 0.52 × length × width2. To determine the microvascular density (MVD), the vessels stained with Meca-32 antibody were counted within 5 random ×400 fields. Any highlighted endothelial cell or cluster that was separate from the adjacent microvessels was considered a single and countable microvessel. The mean value of the counts was taken as the MVD.

For lentiviral preparation, FLAG-tagged CCN2/CTGF or 3xFLAG-tagged CCN2/CTGFI–III sequence was cloned into NheI and SalI sites of PTY-IRES-eGFP vector, in which a single bicistronic mRNA with GFP was expressed under the control of elongation factor 1α promoter. Viruses were produced after cotransfection of lentiviral backbone and packaging plasmids into 293FT cells. Infected LLC cells were collected after FACS analysis based on the intensity of GFP fluorescence, and 0.5 × 106 sorted cells were subcutaneously implanted into flanks of 6-wk-old mice. Tumor growth and the MVD were determined as mentioned above.

Immunofluorescent staining and laser scanning confocal microscopy

Tumors and eyes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde with PBS overnight and cryoprotected with 20% sucrose in PBS followed by OCT embedding. Sections (6–10 μm) were blocked in PBS/10% horse serum/0.1% Tween-20 and stained with the following antibodies: chicken anti-GFP (Abcam), mouse anti-Meca-32 (BD Biosciences), rabbit anti-von Willebrand factor (vWF; Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA), rabbit anti-CCN2/CTGF, α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) with Cy3 conjugation (Sigma-Aldrich), goat anti-Slit3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and rabbit anti-PDGF-B (Abcam). Secondary antibodies included Alexa Fluor 488- or 594-conjugated donkey antibodies (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA). Confocal microscopy was performed with a Leica TCS SP2 system with accompanying SlideBook software (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± sd unless indicated otherwise. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) was evaluated using Student's t test and ANOVA.

RESULTS

Binding of CCN2/CTGF and the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant to CT motifs of multiple angiogenic regulators

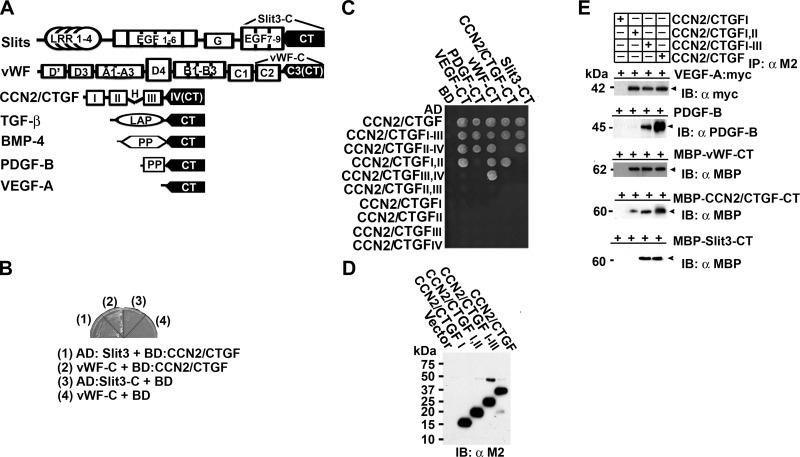

We screened a yeast 2-hybrid cDNA library specific for rat regenerating livers using CCN2/CTGF as bait. Sequence analysis revealed the existence of CT motifs in two different preys. As shown in Fig. 1A, B, one prey (designated as Slit3-C) contained cDNA sequences coding for the 7th–9th epidermal growth factor repeats and the CT motif of Slit3 (GenBank AB011531), which is a neuronal guidance cue and a novel angiogenic factor (15). The second clone (designated as vWF-C) contained a cDNA fragment that encoded the C2 domain and the CT motif of vWF (GenBank XM_342759), which is a well-known endothelial cell marker critical for platelet adhesion during vascular injury and angiogenesis (16, 17). Of interest, Slit3, its homolog Slit2, vWF, CCN2/CTGF itself, and several known CCN2/CTGF binding proteins, such as VEGF-A, TGF-β, and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-4, are key angiogenic regulators and belong to the same cystine knot superfamily (10, 18–20). The angiogenic factor PDGF-B is also a potential interactor in this superfamily, because CCN2/CTGF was initially purified from anti-PDGF IgG affinity chromatography (7). Despite the very divergent primary sequences, crystal structure analyses of some members reveal a striking similarity in their tertiary structure, termed cystine knot, which contains 3 intertwined disulfide bridges formed by 6 conserved cysteine residues. The sections of polypeptides that occur between the two disulfide bonds form a loop through which a third disulfide bond penetrates, forming a rotaxene substructure (18). CT motifs that are primary sequences for cystine knots are located at very C termini of all the members and share a consensus sequence C1-(X)nC2-X-G-X-C3-(X)n-[C]C4XP-Xn-C5-X-C6 (C1-6, 6 conserved cysteines; X, residues except C; G, glycine; P, proline) as shown in Supplemental Fig. S1.

Figure 1.

CCN2/CTGF and the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant bind to CT motifs of multiple angiogenic regulators. A) Schematic representation of CCN2/CTGF and its known or potential interactors with CT motifs. LRR, leucine-rich repeat; EGF, epidermal growth factor repeats; G, a laminin G domain. A mature vWF subunit contains D′, D3, A1, A3, D4, B1, B2, B3, C1, and C2 domains. H represents a hinge region between modules II and III of CCN2/CTGF. Latency-associated peptide (LAP) in TGF-β and propeptides (PP) in BMP-4 and PDGF-B are cleaved to release mature polypeptides that mainly consist of CT motifs. B) BD-fused CCN2/CTGF protein enabled the growth of CG1945 yeast cells on selective medium (synthetic dropout medium with 5 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole lacking histidine, leucine, and tryptophan) when being cotransformed with AD-fused Slit3-C and vWF-C, the 2 preys identified in a yeast 2-hybrid cDNA library screening. C) Yeast growth assay detected interaction in growing CG1945 cells that were cotransformed with BD-fused CT motifs of angiogenic regulators and AD-fused CCN2/CTGF or its mutants on selective medium. D) Western blot analysis detected 3xFLAG-tagged CCN2/CTGF and its mutants in conditioned CHO cell medium. E) The CCN2/CTGF and CCN2/CTGFI–III proteins were specifically associated with all CT motifs tested, whereas the CCN2/CTGFI,II and CCN2/CTGFI mutants bound to some or none of the CT motifs in immunoprecipitation/pull-down assays. Relative amounts of the CCN2/CTGF and its mutants used in the assays are shown in (D. IB, immunoblotting; IP, immunoprecipitation.

These observations led us to hypothesize that CCN2/CTGF recognized CT motifs present in multiple angiogenic regulators. To test this hypothesis, we fused CCN2/CTGF and deletion mutants with transcriptional factor GAL4 AD domain. CT motifs of proposed interactors were fused with GAL4 BD domain. Yeast cells survived on selective medium in the growth assays when interaction occurred and brought GAL4 BD and AD domains to a close proximity that transcriptionally activated His3 reporter gene and synthesized histidine. In this way, we found that CCN2/CTGF and the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant carrying the first 3 modules bound all the CT motifs, despite the fact that CCN2/CTGFI,II, CCN2/CTGFIII,IV, and CCN2/CTGFII–IV mutants bound only some of the CT motifs (Fig. 1C; Supplemental Fig. S2A). In contrast, none of the single modules in CCN2/CTGF nor CCN2/CTGFII,III alone was able to bind any CT motif. To verify the broad binding activity of CCN2/CTGF, we expressed 3xFLAG-tagged CCN2/CTGFI (aa 1–107), CCN2/CTGFI,II (aa 1–184), CCN2/CTGFI–III (aa 1–245), and the full-length CCN2/CTGF proteins in CHO cells (Fig. 1D). CT motifs of Slit3, vWF, and CCN2/CTGF itself were fused with MBP, expressed in E. coli, and used for pull-down assays. Because CT motifs constitute the main part of the growth factor core domains of VEGF-A and mature PDGF-B (21), we transfected the two growth factors in CHO cells expressing CCN2/CTGF or its mutants and used conditioned medium for immunoprecipitation assays. As shown in Fig. 1E, CCN2/CTGF and CCN2/CTGFI–III proteins were specifically associated with all CT motifs tested, whereas the CCN2/CTGFI,II and CCN2/CTGFI mutants bound to only some or none of the CT motifs in immunoprecipitation/pull-down assays. These results confirmed that CCN2/CTGF was able to bind various CT motifs, and its first 3 modules were responsible for the broad binding activity of CCN2/CTGF.

CCN2/CTGF bound to and worked in concert with Slit3 to promote in vitro angiogenesis and downstream Cdc42 activation, whereas the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant inhibited angiogenic actions mediated by CCN2/CTGF and Slit3

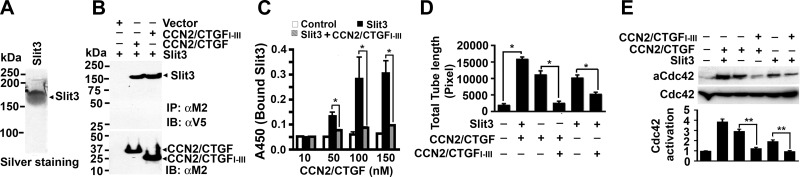

Slit protein is a large ligand for Robo receptors and activates downstream signals such as small GTPase proteins Rho, Rac, or Cdc42, leading to directed cell migration (22). The Slit/Robo pathway has been identified as a new player in angiogenesis. In particular, Slit3 has been reported as a potent angiogenic factor in vitro and in vivo (15, 23). Mice deficient for Slit3 develop altered genesis of the diaphragm and kidney as well as disrupted angiogenesis during embryogenesis (15, 23). To investigate the mutual effect of CCN2/CTGF and Slit3 on angiogenesis, we used our established system to purify 3xFLAG-tagged CCN2/CTGF and CCN2/CTGFI–III proteins by affinity chromatography (4) and developed a new system that allowed us to produce recombinant V5-6xHis-tagged Slit3 protein from conditioned medium of the 293FT-Slit3V5-6xHis/dsRed stable cell line using immobilized metal affinity chromatography, as shown in the silver staining of Fig. 2A. Slit3 protein (∼160 kDa) was able to bind CCN2/CTGF and CCN2/CTGFI–III proteins from cotransfected CHO cells, but not from cells expressing empty vector (Fig. 2B), indicating that Slit3 bound to CCN2/CTGF and CCN2/CTGFI–III protein in tissue culture conditions.

Figure 2.

CCN2/CTGF works in concert with Slit3 to promote in vitro angiogenesis and downstream Cdc42 activation, whereas the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant inhibits the angiogenic actions mediated by CCN2/CTGF and Slit3. A) Silver staining of recombinant Slit3 protein that was tagged with V5-6xHis epitopes and purified from Ni2+ affinity chromatography. B) Slit3 was immunoprecipitated from conditioned media expressing CCN2/CTGF or CCN2/CTGFI–III protein but not from those expressing empty vector. An equal amount of Slit3 protein was input in the assay (not shown). IB, immunoblotting; IP, immunoprecipitation. C) Dose-dependent binding between Slit3 (25 nM) and CCN2/CTGF proteins (10-150 nM) was disrupted in the presence of 0.5 μM CCN2/CTGFI–III protein in solid-phase protein-binding assays. Mock controls gave only background signals in the assays. Data are presented as means ± sd in triplicate wells. *P < 0.01. D) In vitro angiogenesis assays showed total tubule length (in pixels) of HUVECs after stimulation by recombinant CCN2/CTGF (13 nM), Slit3 (1.5 nM), or a mixture of CCN2/CTGF (6.5 nM) and Slit3 (0.8 nM) in the presence or absence of 50 nM CCN2/CTGFI–III protein. Data are presented as means ± sd in triplicate. *P < 0.01. E) Top panel: pull-down assays detected active Cdc42 (aCdc42) protein in HUVECs stimulated by tested proteins in concentration and combination similar to D. Bottom panel: Western blot analysis showed the input of total Cdc42 protein in the assays. Graph panel: the relative level of aCdc42 in relation to that of total Cdc42 proteins was quantified by densitometry analysis. Data are means ± sd from 3 independent experiments. **P < 0.05.

To test whether CCN2/CTGFI–III protein has any effect on CCN2/CTGF and Slit3 interaction, we performed a solid-phase protein-binding assay and measured the amount of Slit3 protein bound to immobilized CCN2/CTGF protein in the presence or absence of CCN2/CTGFI–III protein. As shown in Fig. 2C, Slit3 bound to CCN2/CTGF in a dose-dependent manner, whereas only background binding was observed in the vehicle control. However, when 0.5 μM CCN2/CTGFI–III protein was added in the assay, Slit3 binding to CCN2/CTGF-coated plates was dramatically decreased. Only 12-13% of Slit3 protein remained bound to microplates that were coated with 100 and 150 nM CCN2/CTGF proteins, indicating potent inhibitory activity of the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant on Slit3 and CCN2/CTGF interaction.

Using these purified proteins, we quantitatively determined the effects of recombinant Slit3, CCN2/CTGF, and CCN2/CTGFI–III proteins on in vitro angiogenesis based on tubule structures formed by HUVECs in Matrigel. Quantitative analysis showed that total tubule length in HUVECs exposed to both Slit3 and CCN2/CTGF was 1.4- and 1.6-fold more than that stimulated by CCN2/CTGF or Slit3 alone (Fig. 2D). The small GTPase Cdc42, a downstream molecule of CCN2/CTGF and Slit3 signaling (22, 24), was activated to a greater extent in HUVECs that were exposed to both Slit3 and CCN2/CTGF compared with those exposed to individual protein alone (Fig. 2E). Interestingly, addition of the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant blocked 82 and 48% tube formation mediated by CCN2/CTGF and Slit3, respectively (Fig. 2D). The presence of the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant also greatly blocked Cdc42 activation induced by CCN2/CTGF and Slit3 (Fig. 2E). These observations indicated that CCN2/CTGF worked in concert with Slit3 to promote endothelial tube formation and Cdc42 activation, whereas the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant seemed to gain a dominant-negative function and blocked in vitro angiogenesis mediated by CCN2/CTGF and Slit3.

Slit3 and CCN2/CTGF were colocalized during murine retinal angiogenesis

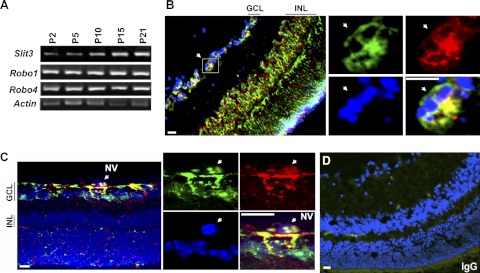

Retinal angiogenesis occurs during the first 3 postnatal weeks in mice. The superficial vascular plexus grows within the ganglion cell layer (GCL) and reaches the periphery of the retina in the first week. Subsequent sprouting from the superficial layer results in the formation of the deep plexus during P7–P15 and the formation of the intermediate plexus during P12–P25 in the inner nuclear layer (INL). We first performed semiquantitative RT-PCR and monitored the temporal and spatial expression patterns of Slit3 and Slit2 and their receptors Robo1 and Robo4 during the time course of retinal angiogenesis. As shown in Fig. 3A, Slit3 mRNA was gradually increased compared with the Actin control. Slit2 mRNA was also gradually up-regulated in a pattern similar to that for Slit3 (Supplemental Fig. S2B). In contrast, Robo1 mRNA did not change very much, and Robo4 mRNA was only induced from P2 to P5 and decreased after that. Real-time quantitative PCR analysis of P7–P21 retinas detected a constant increase of CCN2/CTGF (Fig. 4A), consistent with our previous report (12) and indicating a similar sustained induction pattern among CCN2/CTGF, Slit3, and Slit2 during normal retinal development.

Figure 3.

Slit3 is induced and colocalized with CCN2/CTGF during postnatal retinal development and in the OIR model. A) Real-time semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of Slit3, Robo1, and Robo4 genes during the time course of retinal development. Actin was used as the loading control. B, C) Double immunofluorescent staining for CCN2/CTGF (green) and Slit3 (red) on normal P21 retinas (B) and P17 retinas from mice that were exposed to 75% oxygen at P7–P12 (C). GCL and INL are indicated. Insets with four panels at right show the same areas in the GCL, indicated by a white arrow for CCN2/CTGF (green), Slit3 (red), DAPI (blue), and merged images at high magnification. NV, neovascular cells on preretinal vitreous regions in the OIR model. D) IgG control staining. Scale bars = 25 μm.

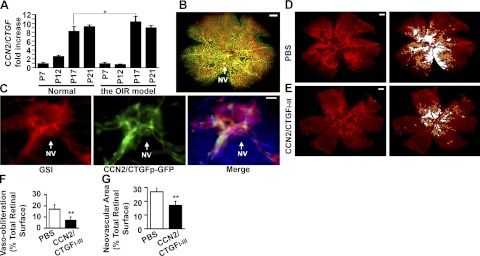

Figure 4.

CCN2/CTGF is highly expressed in the neovascular tuft of the OIR model and intravitreal injection of the CCN2/CTGFI–III protein inhibits vaso-obliteration and neovascularization. A) Real-time quantitative PCR analysis detected the levels of CCN2/CTGF mRNA in some critical time points during normal retinal development and the OIR model. The relative CCN2/CTGF level in each group was normalized with Actin mRNA and compared with those of P7. Data represent means ± sd in triplicate. *P < 0.01. B) Visualization of GFP (green)- and GSI-stained blood vessels (red) in whole mounts of CCN2/CTGFp-GFP retinas from oxygen-exposed P18 eyes. NV, neovascular tufts. C) Visualization of GSI-stained vessels, GFP, and merge in large magnification of the same area indicated by white arrow in B. DAPI was used to stain nuclei. D, E) Representative flat mount preparations of GSI-stained P17 retinas from OIR eyes that were injected with PBS (D) or 2 μg of CCN2/CTGFI–III protein (E). Right panels show areas of vasoobliteration (white) and neovascularization (yellow), as determined by computer-assisted image analyses. F, G) Quantification analyses of vasoobliteration (F) and neovascularization (G) areas in P17 retinas from OIR eyes that received intravitreal injection of PBS or recombinant CTGFI–III proteins. **P < 0.05 (n=9). Scale bars = 0.5 mm (B, D, E); 25 μm (C).

We then performed double-immunofluorescent staining of CCN2/CTGF and Slit3 proteins on retinal cross sections. P10 and P21 that represent the early and end time points of retinal angiogenesis were chosen. As shown in Fig. 3B and Supplemental Fig. S3, abundant CCN2/CTGF and Slit3 proteins were specifically stained in vascularized GCL of P10 and P21 retinas during normal development, as well as P17 retinas in the OIR model. Strong staining of the two proteins was also found in vascularized INL of P21 retinas, whereas minimal staining was seen in avascular INL of P10 retinas. The P17 retinas that were exposed to oxygen in the OIR model had colocalization between CTGF and Slit3 proteins not only in the GCL but also in preretinal cells, which were known to grow above the internal limiting membrane as part of neovascular tufts toward the intravitreous (Fig. 3C). The immunofluorescent staining was specific because little background was found in the IgG control (Fig. 3D). These results supported a close functional relationship between the two proteins during retinal angiogenesis.

CCN2/CTGF was expressed in neovascular tufts and intravitreal injection of the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant inhibited retinal neovascularization in the OIR model

The murine OIR model closely mimics the pathological course in retinopathy of prematurity, a prevalent cause of visual impairment in premature infants, and has been widely used to test the pro- or antiangiogenic activities of many factors in preclinical studies. OIR involves hyperoxia and hypoxia phases. The first phase is characterized by a remission of vascular growth and loss of existing vasculature as a result of exposure to 75% oxygen from P7 to P12. In the second phase, hypoxia as a consequence of animal return to room air after P12 in avascular retinas induces the expression of angiogenic factors leading to proliferative neovascularization. Real-time quantitative PCR analysis detected 0.8-, 10.5-, and 9.1-fold changes of CCN2/CTGF mRNA in retinas of oxygen-treated mice at P12, P17, and P21, respectively, in comparison with normal P7 retinas in the OIR model. In contrast, there were 2.6-, 8.3-, and 9.4-fold increases of CCN2/CTGF mRNA in normal retinas of P12, P17, and P21 mice (Fig. 4A). Thus, CCN2/CTGF fluctuated greatly in the OIR model, whereas its expression was constantly elevated during normal retinal angiogenesis.

We treated transgenic mice expressing GFP under the control of the CCN2/CTGF promoter (CCN2/CTGFp-GFP) in the OIR model and further tested whether CCN2/CTGF was expressed in pathological neovascular tufts in P18 retinal flat mounts. As shown in Fig. 4B, C, we found that CCN2/CTGF-expressing cells as indicated by the GFP reporter were extensively distributed in retinal vascular beds and tightly associated with neovascular tufts that were characterized by tortuous structures and strong staining with GSI. These observations indicated active involvement of CCN2/CTGF in OIR.

We took a further pharmacological approach and tested whether intravitreal injection of the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant in the early hypoxia stage affected the development of OIR. Retinas with maximal neovascularization at P17 were analyzed after GSI staining. As shown in Fig. 4D, E, PBS-treated collateral retinas developed numerous tortuous vascular tufts in the midperiphery halfway between the central retina and the more vascularized peripheral retina. In contrast, retinas that received intravitreal injection of 2 μg of CCN2/CTGFI–III protein had fewer avascular areas and less neovascular tufts. Quantitative analyses demonstrated that avascular areas were 16.8 ± 4.0% of total retinal surfaces in PBS-treated eyes and decreased to 7.4 ± 2.4% in CCN2/CTGFI–III treated eyes (Fig. 4F). Neovascularization areas were 27.3 ± 3.0% of total retinal surfaces in PBS-treated eyes and reduced to 17.3 ± 3.0% in CCN2/CTGFI–III treated eyes (Fig. 4G). It seemed that intravitreal injection of the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant caused a 56% reduction in vascular obliteration and a 37% decrease in retinal neovascularization vs. saline injection, indicating that this mutant inhibited the formation of pathological neovascular tufts and simultaneously promoted physiological revascularization in hypoxic P17 retinas.

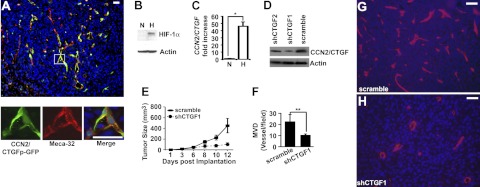

CCN2/CTGF was expressed in tumor endothelial cells, induced in hypoxic tumor cells, and important for LLC tumorigenesis and angiogenesis

We explored the role of CCN2/CTGF in pathological angiogenesis using the second mouse model based on the fact that most solid tumors develop regions of hypoxia and induce blood vessel growth through the recruitment of host vessels as they grow to certain sizes. To test whether CCN2/CTGF was expressed in host-derived tumor vessels, we implanted syngeneic LLC cells subcutaneously in flanks of CCN2/CTGFp-GFP transgenic mice. Using Meca-32 antibody for endothelial cells and GFP reporter for CCN2/CTGF expression, we stained intratumoral vessels and found a strong promoter activity of CCN2/CTGF in Meca-32+ endothelial cells (Fig. 5A). In addition, we tested whether LLC cells could be another source of CCN2/CTGF using an in vitro hypoxia culture system. Based on the fact that the transcriptional factor HIF-1α subunit is normally degraded by the proteasome machinery but becomes stabilized under hypoxia, we validated the in vitro hypoxia culture system by detecting the accumulation of HIF-1α protein under hypoxia in Western blot analysis (Fig. 5B). Real-time quantitative PCR analysis showed a 48-fold increase of CCN2/CTGF mRNA in response to hypoxia (Fig. 5C), indicating CCN2/CTGF induction in hypoxic LLCs. To test whether CCN2/CTGF expression was necessary for LLC tumorigenesis, we designed two shRNAs corresponding to CCN2/CTGF coding sequences 955-979 and 606-624 (shCTGF1 and shCTGF2) and delivered them into LLCs using adenovirus systems. As shown in Fig. 5D, shCTGF1 effectively knocked down the level of CCN2/CTGF protein compared with shCTGF2 and scramble controls in hypoxic LLC cells. Moreover, tumors expressing shCTGF1 grew slower than those of scramble controls (Fig. 5E) and shCTGF2 (data not shown) in growth curve analyses. Further immunofluorescent staining for the endothelial marker Meca-32 revealed that shCTGF1 tumors had 10.6 ± 0.8 microvessels/field, whereas scramble tumors developed 22.8 ± 6.2 microvessels/field at d 12 postimplantation, suggesting 1.2-fold less MVD in shCTGF1 tumors than in scramble controls (Fig. 5F–H). These results demonstrated an importance of expression in LLC tumorigenesis.

Figure 5.

CCN2/CTGF is expressed in tumor endothelial cells and hypoxic LLC cells, whereas knockdown of CCN2/CTGF by shRNA affects LLC tumorigenesis. A) Dual staining of GFP and Meca-32 on sections of tumors that were grown on CCN2/CTGFp-GFP transgenic mice. Insets at bottom show high-magnification views of boxed area. B) Western blot analysis detected stabilized HIF-1α protein in hypoxic LLC cells. N, normoxia; H, hypoxia. C) CCN2/CTGF induction in the hypoxic LLCs in real-time quantitative PCR analysis. Relative level of CCN2/CTGF mRNA under hypoxia was normalized with Actin and compared with those of normoxia. Data represent means ± sd in triplicate. *P < 0.01. D) Western analyses detected the levels of CCN2/CTGF protein in hypoxic LLCs infected with recombinant adenoviruses expressing shCTGF1, shCTGF2, and scramble. Actin was used for the loading controls in B and D. E) Growth curve analysis of indicated tumors (n=3). Bars indicate means ± se. F) Quantitative analysis shows decreased MVD in shCTGF1 tumors compared with that in scramble controls. Meca-32+ microvessels per field at ×400 view were counted. **P < 0.01. G, H) Representative images show the Meca-32 staining on sections of tumors infected with recombinant adenoviruses for scramble (G) and shCTGF1 (H). DAPI was used to stain nuclei. Scale bars = 20 μm.

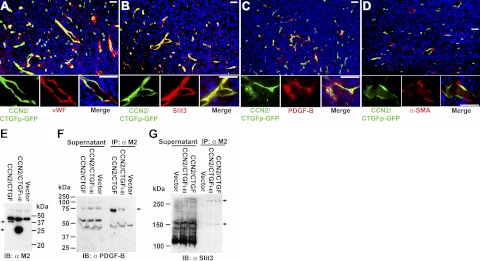

CCN2/CTGF was not expressed in α-SMA+ pericytes, but coexpressed with multiple angiogenic regulators in endothelial cells and CCN2/CTGF protein directly bound to Slit3 and PDGF-B in LLC tumors

To determine whether CCN2/CTGF was associated with angiogenic regulators with CT motifs in vivo, we performed immunofluorescent staining of vWF, PDGF-B, and Slit3 on sections of LLC tumors that were implanted into CCN2/CTGFp-GFP mice. As shown in Fig. 6A–C, all three proteins were stained strongly around intratumoral vessels and colocalized with GFP signal, indicating that CCN2/CTGF was coexpressed with them in the same types of microvascular cells. Endothelial cells and pericytes are two major types of microvascular cells. However, pericytes expressing α-SMA were not positive for GFP signal, indicating that intratumoral endothelial cells were the major source of CCN2/CTGF in LLCs. This observation was consistent with our results in Fig. 5A and literature results regarding the endothelial production of vWF, PDGF-B, and Slit3 (15, 17, 21).

Figure 6.

CCN2/CTGF is coexpressed with multiple angiogenic regulators in α-SMA− cells and binds to Slit3 and PDGF-B in LLC tumors. Experiment shown is representative of 2 performed. A–D) Double immunofluorescent staining for vWF (A), Slit3 (B), PDGF-B (C), and α-SMA (D) antibodies on tumors from CCN2/CTGFp-GFP mice. Insets show high-magnification views of the same areas. Scale bars = 20 μm. E) Western blot analysis detected FLAG-tagged CCN2/CTGF and 3xFLAG-tagged CCN2/CTGFI–III proteins in indicated tumors. NS, nonspecific band. F, G) PDGF-B antibody (F) and Slit3 antibody (G) detected immunoreactive bands from supernatants and immunoprecipitates of indicated tumors in the assays. Arrows indicate products specific for tumors expressing CCN2/CTGF and CCN2/CTGFI–III. IB, immunoblotting; IP, immunoprecipitation.

To provide direct evidence of in vivo binding, we used a lentiviral delivery system and ectopically expressed empty vector, FLAG-tagged CCN2/CTGF, and 3xFLAG CCN2/CTGFI–III proteins in primary LLC tumors (Fig. 6E). Immunocomplexes were pulled down from supernatants of total protein lysates using M2 antibody-conjugated agarose. As shown in Fig. 6F, two kinds of PDGF-B immunoreactive products (∼45 and ∼75 kDa) were detected in the immunoprecipitation assays. Although bands with similar sizes of the two products were present in supernatants of all three types of tumors, the 75-kDa product seemed to be specific for CCN2/CTGF- and CCN2/CTGFI–III-expressing tumors because it was not pulled down from control tumors expressing empty vector. We took a similar approach to determine Slit3 binding to CCN2/CTGF and its mutant. As shown in Fig. 6G, two products that were immunoreactive to rabbit Slit3 antibody were detected from immunocomplexes that were pulled down from CCN2/CTGF and CCN2/CTGFI–III tumors. One product (∼160 kDa) might be the full-length Slit3 with expected size and the other product (>250kDa) might be a large Slit3 complex. Although other products with different size were immunoreactive to the Slit3 antibody in supernatants of all three types of tumors, none of them was detected in immunoprecipitates. These results indicate that CCN2/CTGF and CCN2/CTGFI–III proteins were associated with both PDGF-B and Slit3 as large complexes in primary LLC tumors.

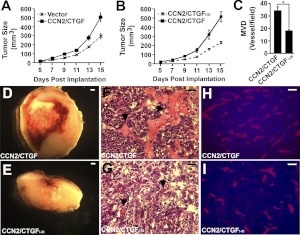

Ectopic expression of CCN2/CTGF and CCN2/CTGFI–III gave rise to distinct LLC tumorigenesis and angiogenesis

To further elucidate the function of CCN2/CTGF and its deletion mutant in LLC tumorigenesis, we compared the growth and angiogenesis of tumors that contained empty vector, FLAG-tagged CCN2/CTGF, and 3xFLAG-tagged CCN2/CTGFI–III. The CCN2/CTGF tumors appeared to grow faster than vector control tumors after d 7 postimplantation in the growth assay, indicating a protumorigenic activity of CCN2/CTGF (Fig. 7A). However, CCN2/CTGFI–III did not exhibit such action, because tumors bearing this mutant grew significantly slower than the CCN2/CTGF tumors (Fig. 7B). Morphological comparison analysis and hematoxylin and eosin staining showed large areas of hemorrhage and necrosis in central areas of almost all the CCN2/CTGF tumors at d 15 postimplantation, whereas the CCN2/CTGFI–III tumors only developed modest necrosis and hemorrhage at the same endpoints (Fig. 7D–G). Moreover, Meca-32 staining for blood vessels detected 34.5 ± 2.8 microvessels/field in CCN2/CTGF tumors and 18.3 ± 0.6 microvessels/field in CCN2/CTGFI–III tumors (Fig. 7C, H, I), suggesting decreased MVD in CCN2/CTGFI–III tumors. These results indicated that CCN2/CTGFI–III was devoid of protumorigenic and proangiogenic activities of CCN2/CTGF in LLCs.

Figure 7.

Ectopic expression of the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant reduces CCN2/CTGF-mediated LLC tumorigenesis and angiogenesis. A, B) Growth-curve analyses of tumors infected with indicated recombinant lentiviruses; n = 4 (A); n = 8 (B). Bars indicate means ± se. C) Quantification analysis shows the MDV of CCN2/CTGFI–III and CCN2/CTGF tumors. *P < 0.01. D–I) Representative images show morphological comparison (D, E), hematoxylin and eosin staining (F, G), and Meca-32 staining (H, I) of indicated tumors. Arrows in D and E indicate blood vessels with erythrocytes that do not contain nuclei. Scale bars = 0.1 mm (D, E); 20 μm (F–I).

To test whether this mutant affected CCN2/CTGF binding to its partners in the LLC model, we established an LLC cell line that overexpressed 3xFLAG-tagged CCN2/CTGFI–III and a control cell line that only expressed lentiviral vector after flow cytometric sorting based on coexpressed GFP marker (Supplemental Fig. S4A–C). We further introduced CCN2/CTGF:myc protein into these cells as shown in Supplemental Fig. S4D. Immunoprecipitation assays were performed to examine whether overexpression of this mutant influenced PDGF-B and Slit3 association with CTGF/CCN2 in LLC cells. As shown in Supplemental Fig. S4E, a complex (∼75 kDa) that was immunoreactive to PDGF-B was precipitated with myc antibody from vector LLC cells, whereas little of this complex was immunoprecipitated from CCN2/CTGFI–III LLC cells. The endogenous level of Slit3 was very low in cultured LLC cells. To facilitate the detection of bound Slit3, we cotransfected Slit3:V5 and CCN2/CTGF:myc into the two types of LLC cells. The immunoprecipitation assay using the myc antibody also detected little Slit3:V5 in immunocomplexes from cells that expressed the mutant protein (Supplemental Fig. S4F). These results showed that overexpression of the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant in LLCs greatly inhibited the formation of CCN2/CTGF complexes with PDGF-B and Slit3. Consistent with these observations, the mutant cell line developed significantly smaller tumors than the vector cell line when the cells were implanted into two flanks of the same cohort of mice (Supplemental Fig. S4G). These data confirmed the dominant-negative function of CCN2/CTGFI–III in LLC tumorigenicity.

DISCUSSION

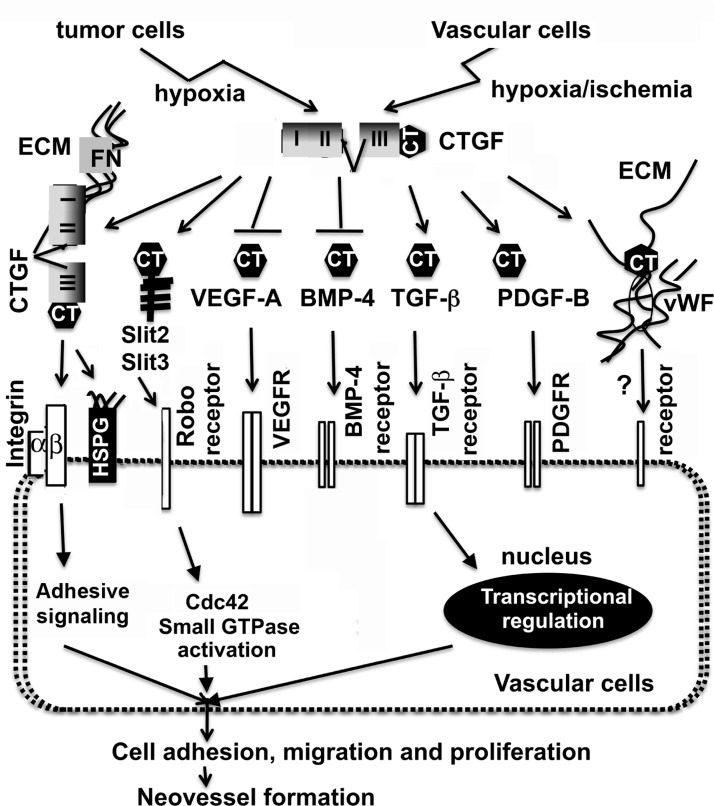

This article presents a unique function of CCN2/CTGF on extracellular signaling through its broad affinity to a series of angiogenic regulators with common CT motifs. A mutant containing the first 3 modules of CCN2/CTGF possessed this broad binding ability, gained a dominant-negative effect on in vitro angiogenesis, inhibited oxygen-induced retinal neovascularization, and lost the protumorigenic and proangiogenic function of CCN2/CTGF in LLC tumors.

Some new findings emerged through vascular-specific expression of CCN2/CTGF in retinas during development, in response to hyperoxic injury and ischemia/hypoxia as well as in LLC tumorigenesis. In normal retinal development, CCN2/CTGF was constantly increased, and CCN2/CTGF protein was localized in GCL and INL where the retinal vasculature was located. In contrast, a fluctuation of CCN2/CTGF expression was found in the OIR model. CCN2/CTGF was decreased concomitantly with hyperoxia-induced regression of the superficial vascular layer and suppression of the deep vascular layer in central areas of P12 retinas in the OIR model. A subsequent increase of CCN2/CTGF was correlated with maximal retinal neovascularization at P17, consistent with the identification of CCN2/CTGF as one of up-regulated genes from a comprehensive gene expression profile study (25). The active involvement of CCN2/CTGF in vascular remodeling was further supported by strong expression of CCN2/CTGF in elongated vascular cells within neovascular loci of ischemic retinas from P18 transgenic reporter mice. Unexpectedly, CCN2/CTGF was prominently expressed in endothelial cells but not pericytes in LLC tumors, even though active pericytes are found to express CCN2/CTGF in tissue culture conditions and fibrotic lesions (26, 27). Tumor vessels are dilated and tortuous, with endothelial hyperplasia as well as reduced polarization and attachment in pericytes. Considering that overexpression of CCN2/CTGF induces deadhesion and apoptosis in aortic smooth muscle cells and retinal pericytes (28, 29), we speculated that CCN2/CTGF induced apoptosis in pericytes/vascular smooth muscle cells but simultaneously stimulated endothelial cell activation and survival in LLC tumors, although further studies are needed to test this hypothesis.

The cystine knot superfamily consists of several subfamilies of growth factors (TGF-β, BMPs, VEGFs, and PDGFs), guidance cue Slits, and adhesion molecule vWF. The majority of the members of the cystine knot superfamily could bind to their receptors on the cell surface, leading to activation of downstream intracellular effectors controlling cell behavior and fates. So far, CT motifs are found in genomes of nematode, Drosophila, and other higher species but not in the unicellular yeast, indicating its evolvement from extracellular signaling molecules of multicellular organisms (19). Almost all CT motifs bound to CCN2/CTGFI–III and CCN2/CTGFII-IV mutants, indicating the importance of modules II and III for the broad binding affinity. Module II is the von Willebrand factor type C (VWC) domain and module III is the thrombospondin (TSP) domain, both of which have been reported to mediate oligomerization. We believe that this oligomerization controls the activity or bioavailability of the CT motif-containing ligands and their signal pathways based on the following observations. First, CCN2/CTGF weakly binds to TGF-β1 and potentiates the effects of limiting amounts of TGF-β1, indicating that CCN2/CTGF functions as a chaperone to modify the conformation or solubility of TGF-β1 and facilitates presentation to its cognate receptors (20). Second, CCN2/CTGF strongly binds BMP-2, -4, and -7 and antagonizes their biological activities and signaling in several biological systems (20, 30). Third, CCN2/CTGF sequesters VEGF-A by forming an inactive complex with VEGF-A and prevents VEGF-A signaling (10). Besides the TSP motif, the VWC module could be another VEGF-A binding site because the CCN2/CTGFI,II mutant (1–184 aa) carrying the first two modules and the hinge region of CCN2/CTGF was able to bind VEGF-A in this study. Moreover, 3 new CCN2/CTGF binding proteins of the cystine knot superfamily (vWF, Slit3, and PDGF-B) were identified. Although the binding kinetics between these angiogenic regulators and CCN2/CTGF remain to be determined in the future, several pieces of evidence support the fact that CCN2/CTGF regulates their activities and bioavailability. For example, the levels of PDGF and PDGF receptors are dramatically decreased in developing lung of CCN2/CTGF-knockout mice (31). Hall-Glenn et al. (32) show that CCN2/CTGF potentiates PDGF-B signaling and is essential for pericyte adhesion and endothelial basement membrane formation during angiogenesis. We found that CCN2/CTGF and Slit3 worked in concert to promote in vitro angiogenesis and downstream Cdc42 signaling. Slit3 and CCN2/CTGF were colocalized in angiogenic sites of developing retinas and physically bound each other during LLC tumorigenesis. Module III (TSP domain) seemed to be necessary for both PDGF-B and Slit3 binding because the CCN2/CTGFI,II mutant lacking this module was insufficient for binding even in sensitive yeast two-hybrid analysis of this study. vWF is a large multimetric protein with a well-known function in platelet adhesion during vascular injury. This study showed that vWF bound to both the N- and C-terminal halves of CCN2/CTGF in yeast. Both CCN2/CTGF and vWF were also coexpressed in tumor endothelial cells at angiogenic sites, indicating that the two adhesive molecules might synergize to induce cell attachment in ECM during angiogenesis and vascular injury. Figure 8 summarizes the potential angiogenic actions of CCN2/CTGF. Besides its roles as an extracellular signal modulator for CT motif-bearing ligands, CCN2/CTGF has been known to mediate adhesive signaling and promote angiogenesis through binding to the ECM protein fibronectin, cell surface receptors heparin sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs), and integrins. Considering that angiogenesis requires the interplay between integrins and growth factor receptors, it is plausible that the broad binding ability of CCN2/CTGF enables this molecule to integrate various angiogenic signals that affect intracellular effectors, leading to fine-tune regulation of vascular cell adhesion, migration, and proliferation in a contextual dependent manner.

Figure 8.

Model of the potential roles of CCN2/CTGF during angiogenesis. In response to hypoxia/ischemia, CCN2/CTGF is induced in vascular cells and tumor cells. The secreted product can promote angiogenesis in part by mediating adhesive signaling and binding to the ECM protein fibronectin and cell surface receptors integrins and HSPGs. In addition, CCN2/CTGF recognizes CT motifs that are conserved in a series of angiogenic regulators. CCN2/CTGF can inhibit VEGF-A and BMP-4 signaling, but promote the signaling elicited by TGF-β and PDGF-B. Its concerted action with Slit3 potentiates the activation of the downstream small GTPase Cdc42. Although its mutual effect with adhesion molecule vWF is still unknown, modulation of the above key pathways will affect intracellular effectors, leading to the regulation of vascular cell adhesion, migration, and proliferation. Considering that cross-talk between integrins and growth factor receptors is critical for angiogenesis, it is likely that the broad binding ability of CCN2/CTGF enables this molecule to integrate various angiogenic signals and contributes to fine-tune regulation of blood vessel growth in a contextual dependent manner.

Slit proteins were originally identified as neuronal guidance cues involved in axon pathfinding and branching as well as neuronal cell migration. The presence of commonalities in both neural and vascular growth has led to extended investigation about the roles of Slits in angiogenesis. Many studies have been focused on Slit2. Purified recombinant Slit2 protein promotes both in vitro and in vivo angiogenesis. However, in the presence of other regulators such as ephrin-A1, Slit2 switches from proangiogenesis to antiangiogenesis, at least through inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2-dependent activation of Akt and Rac GTPase (33). In addition, Slit2 can activate the Robo4 receptor and suppress VEGF-induced endothelial cell migration, assembly, and permeability (34). Slit2 and Slit3 share ∼60% homology. The two Slit proteins not only interacted with CCN2/CTGF and its mutants in the yeast two-hybrid analyses but also increased at the mRNA levels in a similar pattern during postnatal retinal development. Perhaps, Slit3 shares the same mechanism as Slit2 with both proangiogenic and antiangiogenic potentials in vivo. Given the fact that intraocular injection of exogenous Slit2 inhibited neovascularization and vascular leak in mouse models (34), Slit3 may be antiangiogenic in retinal neovascularization and tumor angiogenesis. This possibility does not conflict with our observations about the concerted interaction of CCN2/CTGF with Slit3 to promote angiogenesis because the overall outcome of neovessel formation is a balance of proangiogenic and antiangiogenic factors.

One interesting outcome of our study design is that the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant gained antiangiogenic potential in vitro and in vivo. There are several possible explanations to account for the ability of CCN2/CTGFI–III to reduce pathological angiogenesis in hypoxic retinas and LLC tumors. First, the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant did not contain a CT motif, a binding site for important signaling molecules such as ECM protein fibronectin, cell surface receptors HSPGs, and integrins. Consequently, the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant may become less associated with ECM and cells and more soluble in serum and body fluid compared with intact CCN2/CTGF. Second, Slit3, PDGF-B, vWF, and CCN2/CTGF itself are important angiogenic regulators and have been shown to be up-regulated in OIR, tumorigenesis, and many other diseases. The broad binding ability of the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant may deprive the retinas of these angiogenic factors critical for multiple angiogenic pathways, thereby inhibiting pathological angiogenesis. Thus, unlike CCN2/CTGF, which acts as an adhesive molecule to recruit and enrich angiogenic regulators on ECM and the cell surface, the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant may bind multiple angiogenic factors and affect their biological activities and bioavailability, leading to decreased angiogenic signals. In agreement with this concept, CCN5 lacks this CT motif and is a heparin-induced growth arrest specific gene in vascular smooth muscle cells (35). Modules I, II, and III between CCN2/CTGF and CCN5 share 45% identity and 26 conserved cysteine residues (36). Recently, CCN5 has been shown to mediate a dominant-negative function of CCN2/CTGF in murine cardiac fibrosis models (37). Last, the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant directly interacts with VEGF-A, the angiogenic master regulator, both in vitro and in vivo (10). VEGF-A has been shown to be required for pathological but not physiological angiogenesis (38). Perhaps, the dominant-negative effect of the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant outweighs proangiogenic activity of VEGF-A, resulting in more physiological angiogenesis and less pathological angiogenesis in the OIR model. It will be intriguing to test whether the CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant could be effectively useful for antiangiogenic therapy in future clinical studies.

Cross-talk among the various molecular and cellular components of the angiogenic microenvironment and the establishment of gradients between this region and the local vasculature are critical determinants of the extent and pattern of angiogenesis. This study demonstrated CCN2/CTGF as a critical extracellular modulator of angiogenesis by binding to a group of key angiogenic regulators with conserved CT motifs, probably through oligomerization of modules II and III. This novel action of CCN2/CTGF may lead to several modulatory effects such as protection binding proteins from proteolytic destruction, sequestering factors in ECM at the sites of an injury, and stabilizing or destabilizing angiogenic ligand/receptor interactions. Our finding is consistent with the first structural determinants of CCNs using small-angle X-ray scattering, in which CCN proteins exist in the ECM as long extended scaffolds able to move and flex to allow multiple modules to bind a ligand (39). The CCN2/CTGFI–III mutant with a broad binding activity and a potent antiangiogenic activity shows therapeutic potential that may affect multiple key angiogenic pathways. Further understanding of the binding of CCN2/CTGF and its bioactive isoforms/mutants with angiogenic regulators of the cystine knot superfamily may hold promise as a strategy of rational therapeutic design for the prevention or treatment of aberrant angiogenesis in cancer and vascular and fibrotic disorders of many organs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Emina Huang, Long Dang, Robert Fisher, and Tom Shupe for manuscript discussion. The authors also thank Dr. Wen-Yuan Song (University of Florida) for providing the pPC97, pPC96, and pMAL vectors.

The authors acknowledge the U.S. National Institutes of Health (grants HL070738 and EY018158 to E.W.S.; T32 DK074367 to L.P.; EY005587 to G.S.S.; and EY021721 to W.W.H.) and Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc. for partial support of this work. W.W.H. and the University of Florida have a financial interest in the use of adeno-associated virus therapies and own equity in a company (AGTC Inc.) that might, in the future, commercialize some aspects of this work.

The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- AD

- activation domain

- BD

- binding domain

- BMP

- bone morphogenetic protein

- CCN

- cysteine-rich 61/connective tissue growth factor/nephroblastoma

- Cdc42

- cell division cycle 42 GTP-binding protein

- CT

- C-terminal cystine knot

- CTGF

- connective tissue growth factor

- GCL

- ganglion cell layer

- GSI

- Griffonia simplicifolia isolectin IB4

- HIF

- hypoxia inducible factor

- HRP

- horseradish peroxidase

- HSPG

- heparin sulfate proteoglycan

- HUVEC

- human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- INL

- inner nuclear layer

- LLC

- Lewis lung carcinoma

- MBP

- maltose binding protein

- MVD

- microvascular density

- OIR

- oxygen-induced retinopathy

- P

- postnatal day

- PDGF

- platelet derived growth factor

- PFU

- plaque forming unit

- Robo

- Roundabout

- shCTGF1

- short hairpin RNAs of CCN2/CTGF sequence 1

- shCTGF2

- short hairpin RNAs of CCN2/CTGF sequence 2

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA

- SMA

- smooth muscle actin

- TBS

- Tris-buffered saline

- TSP

- thrombospondin

- vWF

- von Willebrand factor

- VWC

- von Willebrand factor type C

REFERENCES

- 1. Fong G. H. (2008) Mechanisms of adaptive angiogenesis to tissue hypoxia. Angiogenesis 11, 121–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Loges S., Roncal C., Carmeliet P. (2009) Development of targeted angiogenic medicine. J. Thromb. Haemost. 7, 21–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jun J. I., Lau L. F. (2011) Taking aim at the extracellular matrix: CCN proteins as emerging therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 10, 945–963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pi L., Ding X., Jorgensen M., Pan J. J., Oh S. H., Pintilie D., Brown A., Song W. Y., Petersen B. E. (2008) Connective tissue growth factor with a novel fibronectin binding site promotes cell adhesion and migration during rat oval cell activation. Hepatology 47, 996–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pi L., Oh S. H., Shupe T., Petersen B. E. (2005) Role of connective tissue growth factor in oval cell response during liver regeneration after 2-AAF/PHx in rats. Gastroenterology 128, 2077–2088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shi-Wen X., Leask A., Abraham D. (2008) Regulation and function of connective tissue growth factor/CCN2 in tissue repair, scarring and fibrosis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 19, 133–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bradham D. M., Igarashi A., Potter R. L., Grotendorst G. R. (1991) Connective tissue growth factor: a cysteine-rich mitogen secreted by human vascular endothelial cells is related to the SRC-induced immediate early gene product CEF-10. J. Cell Biol. 114, 1285–1294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Babic A. M., Chen C. C., Lau L. F. (1999) Fisp12/mouse connective tissue growth factor mediates endothelial cell adhesion and migration through integrin alphavbeta3, promotes endothelial cell survival, and induces angiogenesis in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 2958–2966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shimo T., Nakanishi T., Nishida T., Asano M., Sasaki A., Kanyama M., Kuboki T., Matsumura T., Takigawa M. (2001) Involvement of CTGF, a hypertrophic chondrocyte-specific gene product, in tumor angiogenesis. Oncology 61, 315–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Inoki I., Shiomi T., Hashimoto G., Enomoto H., Nakamura H., Makino K., Ikeda E., Takata S., Kobayashi K., Okada Y. (2002) Connective tissue growth factor binds vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and inhibits VEGF-induced angiogenesis. FASEB J. 16, 219–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ivkovic S., Yoon B. S., Popoff S. N., Safadi F. F., Libuda D. E., Stephenson R. C., Daluiski A., Lyons K. M. (2003) Connective tissue growth factor coordinates chondrogenesis and angiogenesis during skeletal development. Development 130, 2779–2791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pi L., Xia H., Liu J., Shenoy A. K., Hauswirth W. W., Scott E. W. (2011) Role of connective tissue growth factor in the retinal vasculature during development and ischemia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52, 8701–8710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smith L. E., Wesolowski E., McLellan A., Kostyk S. K., D'Amato R., Sullivan R., D'Amore P. A. (1994) Oxygen-induced retinopathy in the mouse. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 35, 101–111 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Connor K. M., Krah N. M., Dennison R. J., Aderman C. M., Chen J., Guerin K. I., Sapieha P., Stahl A., Willett K. L., Smith L. E. (2009) Quantification of oxygen-induced retinopathy in the mouse: a model of vessel loss, vessel regrowth and pathological angiogenesis. Nat. Protoc. 4, 1565–1573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang B., Dietrich U. M., Geng J. G., Bicknell R., Esko J. D., Wang L. (2009) Repulsive axon guidance molecule Slit3 is a novel angiogenic factor. Blood 114, 4300–4309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stel H. V., Sakariassen K. S., de Groot P. G., van Mourik J. A., Sixma J. J. (1985) Von Willebrand factor in the vessel wall mediates platelet adherence. Blood 65, 85–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Starke R. D., Ferraro F., Paschalaki K. E., Dryden N. H., McKinnon T. A., Sutton R. E., Payne E. M., Haskard D. O., Hughes A. D., Cutler D. F., Laffan M. A., Randi A. M. (2011) Endothelial von Willebrand factor regulates angiogenesis. Blood 117, 1071–1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McDonald N. Q., Hendrickson W. A. (1993) A structural superfamily of growth factors containing a cystine knot motif. Cell 73, 421–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vitt U. A., Hsu S. Y., Hsueh A. J. (2001) Evolution and classification of cystine knot-containing hormones and related extracellular signaling molecules. Mol. Endocrinol. 15, 681–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abreu J. G., Ketpura N. I., Reversade B., De Robertis E. M. (2002) Connective-tissue growth factor (CTGF) modulates cell signalling by BMP and TGF-beta. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 599–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Andrae J., Gallini R., Betsholtz C. (2008) Role of platelet-derived growth factors in physiology and medicine. Genes Dev. 22, 1276–1312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tanno T., Fujiwara A., Sakaguchi K., Tanaka K., Takenaka S., Tsuyama S. (2007) Slit3 regulates cell motility through Rac/Cdc42 activation in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. FEBS Lett. 581, 1022–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu J., Zhang L., Wang D., Shen H., Jiang M., Mei P., Hayden P. S., Sedor J. R., Hu H. (2003) Congenital diaphragmatic hernia, kidney agenesis and cardiac defects associated with Slit3-deficiency in mice. Mech. Dev. 120, 1059–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crean J. K., Furlong F., Finlay D., Mitchell D., Murphy M., Conway B., Brady H. R., Godson C., Martin F. (2004) Connective tissue growth factor [CTGF]/CCN2 stimulates mesangial cell migration through integrated dissolution of focal adhesion complexes and activation of cell polarization. FASEB J. 18, 1541–1543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sato T., Kusaka S., Hashida N., Saishin Y., Fujikado T., Tano Y. (2009) Comprehensive gene-expression profile in murine oxygen-induced retinopathy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 93, 96–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu S., Shi-wen X., Abraham D. J., Leask A. (2011) CCN2 is required for bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis in mice. Arthritis Rheum. 63, 239–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shiwen X., Rajkumar V., Denton C. P., Leask A., Abraham D. J. (2009) Pericytes display increased CCN2 expression upon culturing. J. Cell. Commun. Signal. 3, 61–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu H., Yang R., Tinner B., Choudhry A., Schutze N., Chaqour B. (2008) Cysteine-rich protein 61 and connective tissue growth factor induce deadhesion and anoikis of retinal pericytes. Endocrinology 149, 1666–1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hishikawa K., Oemar B. S., Tanner F. C., Nakaki T., Fujii T., Luscher T. F. (1999) Overexpression of connective tissue growth factor gene induces apoptosis in human aortic smooth muscle cells. Circulation 100, 2108–2112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maeda A., Nishida T., Aoyama E., Kubota S., Lyons K. M., Kuboki T., Takigawa M. (2009) CCN family 2/connective tissue growth factor modulates BMP signalling as a signal conductor, which action regulates the proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes. J. Biochem. 145, 207–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Baguma-Nibasheka M., Kablar B. (2008) Pulmonary hypoplasia in the connective tissue growth factor (Ctgf) null mouse. Dev. Dyn. 237, 485–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hall-Glenn F., De Young R. A., Huang B. L., van Handel B., Hofmann J. J., Chen T. T., Choi A., Ong J. R., Benya P. D., Mikkola H., Iruela-Arispe M. L., Lyons K. M. (2012) CCN2/connective tissue growth factor is essential for pericyte adhesion and endothelial basement membrane formation during angiogenesis. PLoS One 7, e30562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dunaway C. M., Hwang Y., Lindsley C. W., Cook R. S., Wu J. Y., Boothby M., Chen J., Brantley-Sieders D. M. (2011) Cooperative signaling between Slit2 and Ephrin-A1 regulates a balance between angiogenesis and angiostasis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 404–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jones C. A., London N. R., Chen H., Park K. W., Sauvaget D., Stockton R. A., Wythe J. D., Suh W., Larrieu-Lahargue F., Mukouyama Y. S., Lindblom P., Seth P., Frias A., Nishiya N., Ginsberg M. H., Gerhardt H., Zhang K., Li D. Y. (2008) Robo4 stabilizes the vascular network by inhibiting pathologic angiogenesis and endothelial hyperpermeability. Nat. Med. 14, 448–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lake A. C., Bialik A., Walsh K., Castellot J. J., Jr. (2003) CCN5 is a growth arrest-specific gene that regulates smooth muscle cell proliferation and motility. Am. J. Pathol. 162, 219–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brigstock D. R. (1999) The connective tissue growth factor/cysteine-rich 61/nephroblastoma overexpressed (CCN) family. Endocr. Rev. 20, 189–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yoon P. O., Lee M. A., Cha H., Jeong M. H., Kim J., Jang S. P., Choi B. Y., Jeong D., Yang D. K., Hajjar R. J., Park W. J. (2010) The opposing effects of CCN2 and CCN5 on the development of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 49, 294–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ishida S., Usui T., Yamashiro K., Kaji Y., Amano S., Ogura Y., Hida T., Oguchi Y., Ambati J., Miller J. W., Gragoudas E. S., Ng Y. S., D'Amore P. A., Shima D. T., Adamis A. P. (2003) VEGF164-mediated inflammation is required for pathological, but not physiological, ischemia-induced retinal neovascularization. J. Exp. Med. 198, 483–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Holbourn K. P., Malfois M., Acharya K. R. (2011) First structural glimpse of CCN3 and CCN5 multifunctional signaling regulators elucidated by small angle x-ray scattering. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 22243–22249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.