Abstract

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a lifelong progressive disease with high morbidity and mortality worldwide. Whereas cardiovascular complications are well-known for DM, increasing evidence indicates that diabetics are predisposed to cancer. Understanding of molecular pathomechanisms of cancer in DM is of great importance. Dysregulation of glucose/insulin homeostasis leads to increased production of Reactive Oxygen/Nitrogen Species (ROS/RNS) and consequent damage to chromosomal/mitochondrial DNA, a frequent finding in DM. Long-term accumulation of modified/damaged DNA is well-acknowledged as triggering cancer. DNA-repair is a highly energy consuming process provoking increased mitochondrial activity. Particularly dangerous is a provoked activity of damaged mitochondria leading to a “vicious circle” lowering energy supply and potentiating ROS/RNS production. Mitochondrial dysfunction may be implicated in pathomechanisms of diabetes-related cancer. High risk for infectious disorders and induced viral proto-oncogenic activity may further contribute to cancer provocation. Much attention should be focused on preventive measures in diabetic healthcare, in order to restrict severe diabetes-related complications.

Keywords: Cancer in diabetes, Prognostic risk factors, Preventive diagnostics, Targeted preventive measures, Stress/viral etiology, Advanced technologies

Diabetes mellitus as general risk factor for cancer

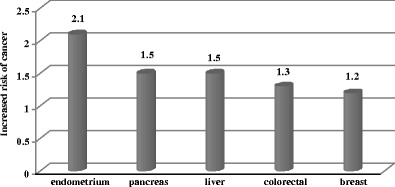

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a group of metabolic disorders, mainly characterized by impaired glucose metabolism and consequent hyperglycemia as the common feature. Whereas cardiovascular complications are well described for DM [1], it is a relatively new consideration that diabetic patients are highly predisposed to cancer. In spite of some ethnic-, gender-, and age-specific differences, significantly increased risk of liver, pancreas, bladder and digestive tract cancer types is generally recognized for DM-patients (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

General predisposition of diabetics to single cancer types: breast [2], endometrial [3], colorectal [4], pancreas [5], and liver [6] cancers

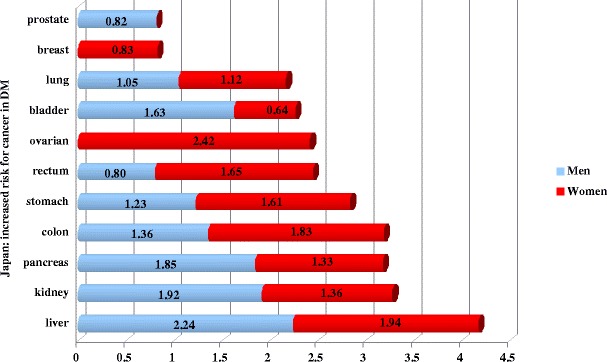

Many population studies indicate an increased risk for almost all kinds of cancer in DM with particular ethnic- as well as gender-dependent preferences (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Population studies in Japan as an example of cancer predisposition of diabetics in years 1990–2003 [7]

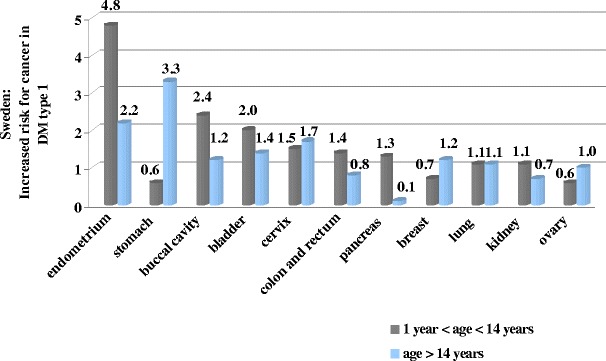

With respect to single DM-types, population studies have been carried out in different countries showing geographic particularities in cancer incidence. Thus, long-term monitoring of a cancer-specific incidence in the subpopulation of type 1 diabetics was performed in Sweden during 1965–1999 [8]. It is noteworthy that particular risk in childhood was demonstrated for endometrial, buccal-cavity, bladder as well as cervix cancer types (Fig. 3). In adulthood, the highest risk has been registered for cancer of stomach, endometrium, cervix, and bladder.

Fig. 3.

Specific cancer incidence with respect to age in Swedish diabetics type 1 registered in years 1965–1999 [8]

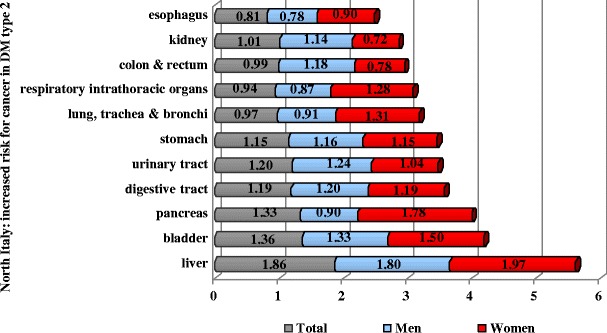

Similar studies carried out for type 2 diabetes demonstrate liver, pancreas and bladder cancer to be the leading types (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Cancer risk for type 2 diabetics in North Italy in years 1987–1996 [9]

Cancer-related mortality in diabetics

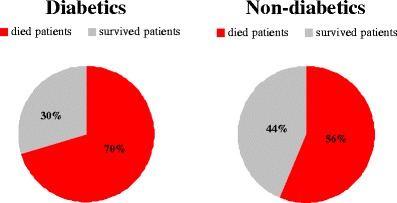

According to the current worldwide statistics, every 10 s one patient dies due to DM-related consequences: DM is currently the fourth leading cause of death [10]. Furthermore, accumulating data demonstrate that, once appeared, cancer outcomes have worse prognosis for diabetics compared to non-diabetic oncologic patients (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Mortality by cancer in diabetic versus non-diabetic patients registered in Netherlands in years 1995–2002 [11]

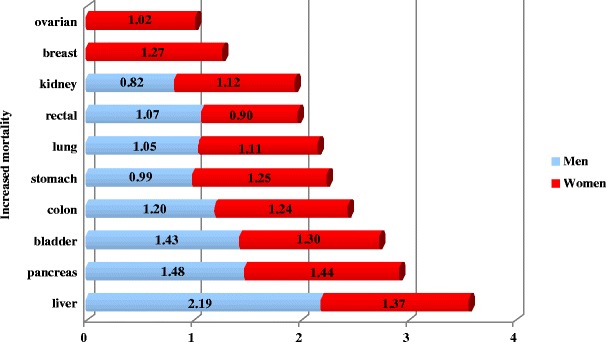

This general figures are well-supported by data collected in USA to treatment of single cancer types as represented in Fig. 6. These data clearly indicate less success in treatment of cancer for DM-patients.

Fig. 6.

Increased mortality of diabetics versus non-diabetics for single cancer types as documented for patients treated in USA in years 1982–1998 [12]

The hindered treatment of oncologic diseases in diabetes care is, however, not the only reason of significantly increased cancer-related mortality of diabetics. Recent studies indicate that diabetics are generally predisposed to cancer development [2–9, 11–22]. Here we overview subcellular and molecular mechanisms that can contribute to cancer-provocation in diabetics.

Subcellular and molecular mechanisms in DM-predisposition to cancer

Mitochondrial dysfunction

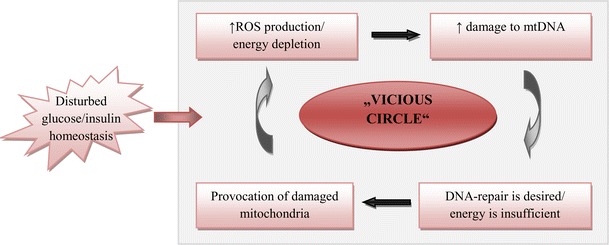

Increased oxidative stress has been implicated in molecular pathomechanisms of DM and majority of chronic diseases developed secondary to diabetes [23–25]. Several studies demonstrated the excessive production of ROS to be the common feature of both diabetes types [10, 22, 26–28]. Disturbed glucose/insulin homeostasis initiates overall cellular stress leading to ir/reversible damage to subcellular structures [28, 29].

Oxidative damage to DNA is well documented for cells isolated from diabetics [30]. These findings indicate an imbalance between the increased production of ROS and decreased DNA-repair capacity. Depending on a quality of cell-cycle controlling machinery, this imbalance can lead either to extensive apoptotic cell lost or proliferation of damaged cells [31]. Whereas the first process causes mainly tissue-degeneration, the latter predisposes to cancer development. Both degenerative alterations in damaged organs and predisposition to cancer have been reported for DM-patients.

Extensive damage to DNA as well as mutations has been demonstrated also for mitochondria in DM-patients [28, 32, 33]. Mitochondrial genetic background as well as mitochondrial stress-response is considered as an important contributor in predisposition to cancer in diabetics [32, 34, 35]. Electron transfer chain (ETC) is the main energy source essential for performance of all cellular functions. Particularly, DNA-repair is a highly energy-consuming machinery, the efficiency of which obligatory depends on the quality of mitochondria. Mitochondrial DNA variations may affect a highly sensitive balance between ETC-efficiency and production of ROS in favor of the latter increasing, therefore, mutagenic effects of ROS and decreasing energy production. This is so called “vicious circle” resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction (Fig. 7). As for mitochondrial protein repertoire, both quantitative and qualitative changes in ND1-ND6 (NADH-dehydrogenases of the ETC-complex I) have been shown to contribute to the “vicious circle” resulting in premature aging and plenty of pathologies including neurodegeneration and cancer [36]. In diabetics, the mitochondrial “vicious circle” has been implicated specifically in individual predisposition to breast cancer [37].

Fig. 7.

Mitochondrial “vicious circle” causes a dangerous imbalance between highly increased production of ROS on one side and low energy production on the other side. Highly increased damage to chrDNA and mtDNA, remarkably decrease repair capacity as well as compromise cell-cycle control are direct consequences of stress-provoked mitochondrial dysfunction [22, 26, 28, 33, 36]

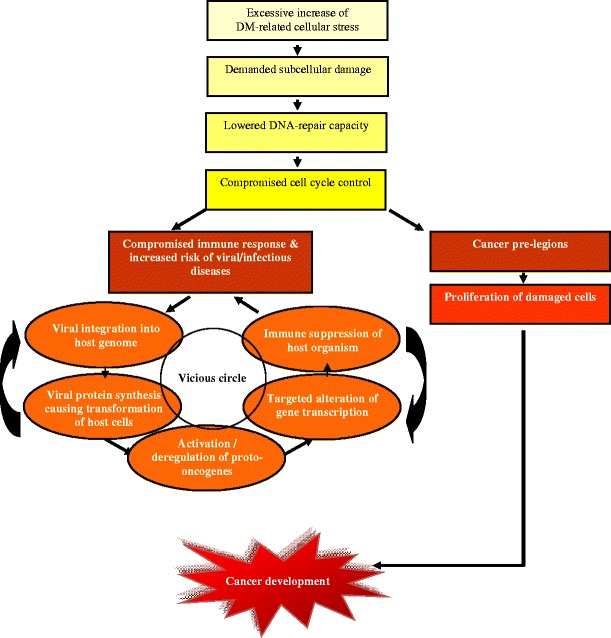

Concept of viral etiology in DM-provoked cancer

Patients with diabetic history are at increased risk of infection [38–40]. There is a growing body of evidence for compromised immune response in this patient cohort as a consequence of metabolic syndrome [41–43]. This imbalance can lead to highly increased incidence of viral infection potentiating cancer risk in diabetics [43–46].

Currently it is already well-acknowledged that more than 15 % of viral infections are able to cause cancer in humans [47]. Thus, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is attributed to 80 % of all human cancers and was proposed to play a central role in molecular pathomechanisms of breast cancer [48–50]. Integration of viral particles in human genome frequently results in activation of several proto-oncogenes, which in turn trigger tumorigenic mechanisms in affected cells [22, 48, 51–53]. Thus, a viral activation of proto-oncogene c-MYC is well described in literature [48]. Thereby, a targeted integration of viral particles in human genome plays the crucial role for consequent cancer development [47, 48, 54]. In this context, HPV demonstrates clear preference for its integration sites, mainly in regions situated closely to c-MYC coding sequences [48]. Once activated, c-MYC protein suppresses the cell-cycle controlling activity of P53, and allows, therefore, the development of new tumorigenic phenotype of transformed human cells [22, 48, 52]. In consensus, the activated synthesis of viral proteins E6, E7, E1 and E2 has been shown to be involved in cancer-related cell transformation [48, 55]. Most relevant mechanisms for viral etiology of cancer predisposition, particularly, in DM-pathology are summarized in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Clue to viral etiology in DM-provoked cancer: “vicious circle” is the particularity of metabolic syndrome with high risk of cancer development [22, 26, 28, 33, 36, 38–45, 51–56]

The overall concept of cancer-predisposition in diabetics

Taking together the above given facts, we conclude that diabetics may be highly predisposed to cancer development specifically due to following contributors [57]:

strong stress factors (excessive metabolic alterations, disturbed glucose/insulin homeostasis, hormonal deregulation, insufficient detoxification) with consequently excessive production of ROS

mitochondrial dysfunction with consequent low energy production, insufficient repair capacity and accumulating damage to both chromosomal and mitochondrial DNA

high risk for infectious disorders with consequently induced viral proto-oncogenic activity as well as activity of particular pathogenic bacterial forms such as Helicobacter pylori.

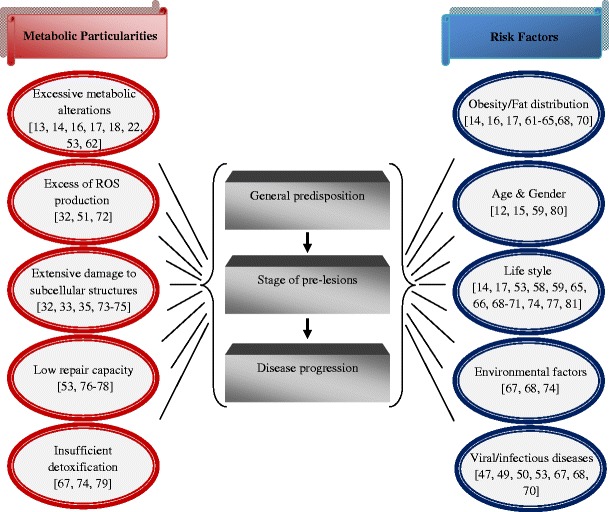

Adequacy of stress response, repair capacity as well as immune defence are highly individual for each patient and strongly depend on risk factors such as genetic background, age, environmental factors, nutrition, body culture, life style, etc. (Fig. 9). Thus, varying breast cancer risk in different ethnic and social groups is well documented [16, 58–60]. Breast fat deposits and distribution increase risk for breast cancer in female and even in male patients [16, 61–65]. In contrast, breast cancer development is significantly reduced in people with regular physical activity [66]. Alcohol abuse and tobacco consumption are further contributors which remarkably increase risk of cancer development [17, 20, 67–71].

Fig. 9.

Particularities of metabolic syndrome and factors contributing to cancer development. Corresponding references are given

Outlook

Current biotechnology possesses sufficient power to estimate the severity of damage to subcellular structures, individual stress reactions and repair capacity. For example, by stress proteome profiling in peripheral leukocytes and blood plasma, individual stress reactions can be well estimated. Advanced predictive diagnostic approaches are currently close to clinical application and allow to select groups of risk and to estimate a predisposition to severe complications in diabetics [34, 82–84].

Much attention should be focused on preventive measures in diabetic healthcare, in order to restrict or even avoid severe secondary complications, such as cancer [85]. Potential groups of risk should be informed about good lifestyle choices. Nowadays, it is increasingly clear that a well-balanced individually created diet is considered as an effective preventive measure and treatment of majority of chronic complications in diabetics [86–88].

References

- 1.Mozaffari MS, Abdelsayed R, Schaffer SW. Diabetic complications: pathogenic mechanisms and prognostic indicators. In: Golubnitschaja O, editor. Predictive diagnostics and personalized treatment: dream or reality? New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larsson SC, Mantzoros CS, Wolk A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:856–62. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friberg E, Orsini N, Mantzoros CS, et al. Diabetes mellitus and risk of endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1365–74. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0681-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1679–87. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang F, Gupta S, Holly EA. Diabetes mellitus and pancreatic cancer in a population-based case-control study in the San Francisco Bay Area, California. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2006;15:1458–63. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adami HO, McLaughlin J, Ekbom A, et al. Cancer risk in patients with diabetes mellitus. Cancer Causes Control. 1991;2:307–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00051670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inoue M, Iwasaki M, Otani T, et al. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of cancer: results from a large-scale population-based cohort study in Japan. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1871–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zendehdel K, Nyrén O, Ostenson CG, et al. Cancer incidence in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus: a population-based cohort study in Sweden. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1797–800. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verlato G, Zoppini G, Bonora E, et al. Mortality from site-specific malignancies in type 2 diabetic patients from Verona. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1047–51. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kowluru RA, Chan PS. Oxidative stress and diabetic retinopathy. Exp Diabetes Res. 2007;2007:43603. doi: 10.1155/2007/43603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poll-Franse LV, Houterman S, Janssen-Heijnen ML, et al. Less aggressive treatment and worse overall survival in cancer patients with diabetes: a large population based analysis. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1986–92. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coughlin SS, Calle EE, Teras LR, et al. Diabetes mellitus as a predictor of cancer mortality in a large cohort of US adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:1160–7. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jee SH, Ohrr H, Sull JW, et al. Fasting serum glucose level and cancer risk in Korean men and women. JAMA. 2005;293:194–202. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xue F, Michels KB. Diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and breast cancer: a review of the current evidence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:823–35. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.3.823S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swerdlow AJ, Laing SP, Qiao Z, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in patients with insulin-treated diabetes: a UK cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:2070–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rose DP, Haffner SM, Baillargeon J. Adiposity, the metabolic syndrome, and breast cancer in African-American and white American women. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:763–77. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mori M, Saitoh S, Takagi S, et al. A review of cohort studies on the association between history of diabetes mellitus and occurrence of cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2000;1:269–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung YW, Han DS, Park KH, et al. Insulin therapy and colorectal adenoma risk among patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus: a case-control study in Korea. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:593–7. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsson SC, Orsini N, Brismar K, et al. Diabetes mellitus and risk of bladder cancer: a meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2819–23. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0468-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suba Z, Ujpál M. Disorders of glucose metabolism and risk of oral cancer. Fogorv Sz. 2007;100:250–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wideroff L, Gridley G, Mellemkjaer L, et al. Cancer incidence in a population-based cohort of patients hospitalized with diabetes mellitus in Denmark. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1360–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.18.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vairaktaris E, Kalokerinos G, Goutzanis L, et al. Diabetes alters expression of p53 and c-myc in different stages of oral oncogenesis. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:1465–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drechsler K, Fikenzer S, Sechtem U, et al. The Euro Heart Survey - Germany: diabetes mellitus remains unrecognized in patients with coronary artery disease. Clin Res Cardiol. 2008;97:364–70. doi: 10.1007/s00392-008-0643-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hofmann MA, Schiekofer S, Isermann B, et al. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from patients with diabetic nephropathy show increased activation of the oxidative-stress sensitive transcription factor NF-kappaB. Diabetologia. 1999;42:222–32. doi: 10.1007/s001250051142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bierhaus A, Schiekofer S, Schwaninger M, et al. Diabetes-associated sustained activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor-kappaB. Diabetes. 2001;50:2792–808. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.12.2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmeira CM, Rolo AP, Berthiaume J, et al. Hyperglycemia decreases mitochondrial function: the regulatory role of mitochondrial biogenesis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;225:214–20. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baynes JW. Role of oxidative stress in development of complications in diabetes. Diabetes. 1991;40:405–12. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.40.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ricci C, Pastukh V, Mozaffari M, et al. Insulin withdrawal induces apoptosis via a free radical-mediated mechanism. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;85:455–64. doi: 10.1139/Y07-029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hou N, Torii S, Saito N, et al. Reactive oxygen species-mediated pancreatic beta-cell death is regulated by interactions between stress-activated protein kinases, p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatases. Endocrinology. 2008;149:1654–65. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frustaci A, Kajstura J, Chimenti C, et al. Myocardial cell death in human diabetes. Circ Res. 2000;87:1123–32. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.12.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Golubnitschaja O. Diabetes mellitus. In: Golubnitschaja O, editor. Predictive diagnostics and personalized treatment: dream or reality? New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohta S. A multi-functional organelle mitochondrion is involved in cell death, proliferation and disease. Curr Med Chem. 2003;10:2485–94. doi: 10.2174/0929867033456440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rolo AP, Palmeira CM. Diabetes and mitochondrial function: role of hyperglycemia and oxidative stress. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;212:167–78. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Golubnitschaja O. Clinical proteomics in application to predictive diagnostics and personalized treatment of diabetic patients. Curr Proteomics. 2008;5:35–44. doi: 10.2174/157016408783955092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu L, Hu Y, Chen B, et al. Mitochondrial polymorphisms as risk factors for endometrial cancer in southwest China. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:1661–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alexeyev MF, Ledoux SP, Wilson GL. Mitochondrial DNA and aging. Clin Sci. 2004;107:355–64. doi: 10.1042/CS20040148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bai RK, Leal SM, Covarrubias D, et al. Mitochondrial genetic background modifies breast cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4687–94. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bener A, Micallef R, Afifi M, et al. Association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and Helicobacter pylori infection. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2007;18:225–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Movahed MR, Hashemzadeh M, Jamal MM. Increased prevalence of infectious endocarditis in patients with type II diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complicat. 2007;21:403–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ojetti V, Migneco A, Silveri NG, et al. The Role of H. pylori Infection in Diabetes. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2005;1:343–7. doi: 10.2174/157339905774574275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foss NT, Foss-Freitas MC, Ferreira MA, et al. Impaired cytokine production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes Metab. 2007;33:439–43. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hopps E, Camera A, Caimi G. Polimorphonuclear leukocytes and diabetes mellitus. Minerva Med. 2008;99:197–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barnea M, Madar Z, Froy O. Glucose and insulin are needed for optimal defensin expression in human cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;367:452–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ali SS, Ali IS, Aamir AH, et al. Frequency of hepatitis C infection in diabetic patients. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2007;19:46–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sangiorgio L, Attardo T, Gangemi R, et al. Increased frequency of HCV and HBV infection in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000;48:147–51. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8227(99)00135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Banerjee S, Banerjee M. Hepatitis C and diabetes mellitus. J Indian Med Assoc. 2006;104:86–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shera KA, Shera CA, McDougall JK. Small tumor virus genomes are integrated near nuclear matrix attachment regions in transformed cells. J Virol. 2001;75:12339–46. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.24.12339-12346.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Popescu NC, Zimonjic DB. Chromosome-mediated alterations of the MYC gene in human cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2002;6:151–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2002.tb00183.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Villiers EM, Sandstrom RE, zur Hausen H et Presence of papillomavirus sequences in condylomatous lesions of the mamillae and in invasive carcinoma of the breast. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:1–11. doi: 10.1186/bcr940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lawson JS, Günzburg WH, Whitaker NJ. Viruses and human breast cancer. Future Microbiol. 2006;1:33–51. doi: 10.2217/17460913.1.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hemann MT, Narita M. Oncogenes and senescence: breaking down in the fast lane. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1–5. doi: 10.1101/gad.1514207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ben-Yosef T, Yanuka O, Halle D, et al. Involvement of Myc targets in c-myc and N-myc induced human tumors. Oncogene. 1998;17:165–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pontén J, Guo Z. Precancer of the human cervix. Cancer Surv. 1998;32:201–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnson CN, Levy LS. Matrix attachment regions as targets for retroviral integration. Virol J. 2005;2:68. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-2-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hebner CM, Laimins LA. Human papillomaviruses: basic mechanisms of pathogenesis and oncogenicity. Rev Med Virol. 2006;16:83–97. doi: 10.1002/rmv.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Golubnitschaja O. Cell cycle checkpoints: the role and evaluation for diagnosis of senescence, cardiovascular, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases. Amino Acids. 2007;32:359–71. doi: 10.1007/s00726-006-0473-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cebioglu M, Schild HH, Golubnitschaja O. Diabetes mellitus as risk factor for cancer: stress or viral etiology? Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2008;8:76–87. doi: 10.2174/187152608784746501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Berger FG. The interleukin-6 gene: a susceptibility factor that may contribute to racial and ethnic disparities in breast cancer mortality. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;88:281–5. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-0726-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pietro PF, Medeiros NI, Vieira FG, et al. Breast cancer in southern Brazil: association with past dietary intake. Nutr Hosp. 2007;22:565–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fejerman L, Ziv E. Population differences in breast cancer severity. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:323–33. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Celis JE, Moreira JM, Cabezón T, et al. Identification of extracellular and intracellular signaling components of the mammary adipose tissue and its interstitial fluid in high risk breast cancer patients: toward dissecting the molecular circuitry of epithelial-adipocyte stromal cell interactions. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:492–522. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500030-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xue Y, Guo XT, Liu WC. Clinical research advancement on male breast cancer. Ai Zheng. 2007;26:1148–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Benchellal Z, Wagner A, Harchaoui Y, et al. Male breast cancer: 19 case reports. Ann Chir. 2002;127:619–23. doi: 10.1016/S0003-3944(02)00816-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Riedl M, Kotzmann H, Luger A. Growth hormone in the elderly man. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2001;151:426–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abu-Abid S, Szold A, Klausner J. Obesity and cancer. J Med. 2002;33:73–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kruk J. Physical activity in the prevention of the most frequent chronic diseases: an analysis of the recent evidence. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2007;8:325–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Irigaray P, Newby JA, Clapp R, et al. Lifestyle-related factors and environmental agents causing cancer: an overview. Biomed Pharmacother. 2007;61:640–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Danaei G, Vander Hoorn S, Lopez AD, et al. Causes of cancer in the world: comparative risk assessment of nine behavioural and environmental risk factors. Lancet. 2005;366:1784–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67725-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P. Risk factors for pancreatic cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2005;95:649–56. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hart AR, Kennedy H, Harvey I. Pancreatic cancer: a review of the evidence on causation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:275–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hermansen K, Jørgensen K, Schmidt EB, et al. Alcohol and lifestyle diseases. Ugeskr Laeg. 2007;169:3404–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dröge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:47–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gago-Dominguez M, Jiang X, Castelao JE. Lipid peroxidation, oxidative stress genes and dietary factors in breast cancer protection: a hypothesis. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:201. doi: 10.1186/bcr1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saikali J, Picard C, Freitas M, et al. Fermented milks, probiotic cultures, and colon cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2004;49:14–24. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc4901_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bonassi S, Znaor A, Norppa H, et al. Chromosomal aberrations and risk of cancer in humans: an epidemiologic perspective. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2004;104:376–82. doi: 10.1159/000077519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Loizidou MA, Michael T, Neuhausen SL, et al. Genetic polymorphisms in the DNA repair genes XRCC1, XRCC2 and XRCC3 and risk of breast cancer in Cyprus. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112:575–9. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9881-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mahabir S, Wei Q, Barrera SL, et al. Dietary magnesium and DNA repair capacity as risk factors for lung cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:949–56. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yu D, Zhang X, Liu J, et al. Characterization of functional excision repair cross-complementation group 1 variants and their association with lung cancer risk and prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2878–86. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Munday R, Zhang Y, Fahey JW, et al. Evaluation of isothiocyanates as potent inducers of carcinogen-detoxifying enzymes in the urinary bladder: critical nature of in vivo bioassay. Nutr Cancer. 2006;54:223–31. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5402_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moenkemann H, Vriese AS, Blom HJ, et al. Early molecular events in the development of the diabetic cardiomyopathy. Amino Acids. 2002;23:331–6. doi: 10.1007/s00726-001-0146-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Howard RA, Freedman DM, Park Y, et al. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and the risk of colon and rectal cancer in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:939–53. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9159-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gahan PB. Circulating nucleic acids in plasma and serum: roles in diagnosis and prognosis in diabetes and cancer. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2008;8:100–8. doi: 10.2174/187152608784746484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Golubnitschaja O. Advanced technologies for prediction of secondary complications in diabetes mellitus. In: Golubnitschaja O, editor. Predictive diagnostics and personalized treatment: dream or reality? New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cebioglu M, Schild HH, Golubnitschaja O. Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for cancer: is predictive diagnosis possible? In: Golubnitschaja O, editor. Predictive diagnostics and personalized treatment: dream or reality? New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Golubnitschaja O. Advanced diabetes care: three levels of prediction, prevention & personalized treatment. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2010;6:42–51. doi: 10.2174/157339910790442637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Page NM, Kemp CF, Butlin DJ, et al. Placental peptides as markers of gestational disease. Reproduction. 2002;123:487–95. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1230487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schweigert FJ. Nutritional proteomics: methods and concepts for research in nutritional science. Ann Nutr Metab. 2007;51:99–107. doi: 10.1159/000102101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mathers JC, Hesketh JE. The biological revolution: understanding the impact of SNPs on diet-cancer interrelationships. J Nutr. 2007;137:253S–8S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.1.253S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]