Abstract

Glaucoma is a major cause of vision loss worldwide with nearly 8 million people bilaterally blind from the disease. This number is estimated to increase over the next 10 years. The key to preventing blindness from glaucoma is effective diagnosis and treatment. The classical glaucoma treatment focuses on intraocular pressure (IOP) reduction. Better knowledge of the pathogenesis has opened up additional therapeutical approaches often called non-IOP lowering treatment. Whilst most of these new avenues of treatment are still in the experimental phase, others are already used by some physicians. These new therapeutic approaches allow a more personalised patient treatment. Non-IOP lowering treatment includes improvements of ocular blood flow, particularly blood flow regulation. This can be achieved by improving the regulation of ocular blood flow (improving autoregulation) by drugs such as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, magnesium or calcium channel blockers. It can also be improved by decreasing blood pressure over-dips. Blood pressure can be increased by an increase in salt intake or in rare cases by treatment with fludrocortisone. Experimentally, glaucomatous optic neuropathy can be prevented by inhibition of astrocyte activation, either by blockage of epidermal growth factor receptor or by counteracting Endothelin. Glaucomatous optic neuropathy can also be prevented by nitric oxide-2 synthase inhibition. Suppression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 inhibits apoptosis of retinal ganglion cells and tissue remodelling. Upregulation of heat shock proteins protects the retinal ganglion cells and the optic nerve head. Reduction of oxidative stress especially at the level of mitochondria also seems to be protective. This can be achieved by gingko, dark chocolate, polyphenolic flavonoids occurring in tea, coffee or red wine and anthocyanosides found in bilberries as well as by ubiquinone and melatonin. This review describes the individual mechanisms which may be targeted by non-IOP lowering treatment based on our pathogenic scheme.

Keywords: Preventive, Personalised, Glaucomatous optic neuropathy, Vascular regulation, Oxidative stress

Introduction

For the past century glaucoma has been considered a disease for which diagnosis and treatment was focussed mainly on intraocular pressure. Large studies such as ‘The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study’ or ‘The European Glaucoma Prevention Study’ recognised ocular hypertension as the most important factor for the development of primary open angle glaucoma. Because elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) was associated with the development of glaucoma, and reducing IOP, reduced the risk of visual field progression, IOP was considered a good surrogate for glaucoma treatment. The focus on IOP as the only risk factor, however, left several questions unanswered: Why do the majority of people with increased IOP not develop glaucomatous optic neuropathy (GON) (Fig. 1)? On the other hand, why do we see an increasing number of patients acquiring GON who have an IOP in the normal range? Why does reduction of IOP, whilst on the average improving prognosis, not stop progression in all patients? And why do some patients need a very low IOP, indeed sometimes an even unphysiological low IOP to stop progression of this disease? These questions can be answered when considering additional risk factors such as systemic hypotension or vascular dysregulation. The elucidation of these additional factors has lead to the investigation of non-IOP lowering treatment. Whether such treatment will be an adjunctive to the conventional IOP-lowering treatment (e.g. in patients with primary open angle glaucoma (POAG)) or whether it shall be used by itself (e.g. in patients with normal-tension glaucoma (NTG)) remains to be seen.

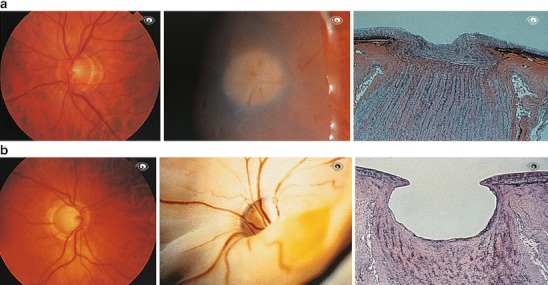

Fig. 1.

Normal optic disc. a Normal optic disc in a healthy person (left), in the eye of a cadaver (middle), and a histological section (right). b Glaucomatous atrophy of the optic disc. The eye of the patient is shown on the left, of a cadaver in the middle and a histological section in the right

Some IOP lowering glaucoma medications have additional effects. For example carbonic anhydrase inhibitors improve regulation of ocular perfusion. This review, however, will focus solely on drugs that do not reduce IOP. Furthermore, we will discuss prevention of GON and only marginally deal with the prevention of IOP increase.

For more details on the pathogenesis and risk factors in glaucoma we refer to the article by Flammer and Mozaffarieh [1]. Fact remains that glaucoma is a multifactorial disease in which the different risk factors known may finally damage through the same or similar pathomechanisms. In order to visualise the individual mechanisms that may be targeted by treatment we have recapitulated the figure of the pathogenic scheme by Flammer and Mozaffarieh (Fig. 2) [1]. The section numbers below correspond to the numbers in Fig. 1.

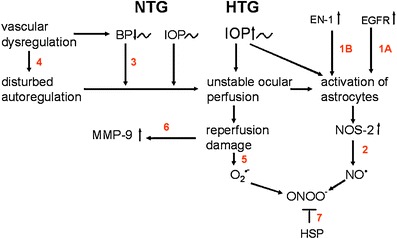

Fig. 2.

The pathogenetic scheme of GON. The pathogenetic scheme by Flammer and Mozaffarieh [1], depicts the individual mechanisms that may be targeted by non-IOP lowering treatment. The numbers in red correspond to the section numbers in the manuscript

Therapeutic targets

-

Inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) prevents the activation of astrocytes and improves ocular blood flow

- Combat of mechanical stress prevents the activation of astrocytes

The activation of the astrocytes in the optic nerve head (ONH) and retina plays an essential role in the pathogenesis of GON [2–4]. Both mechanical and ischemic stress can lead to activation of astrocytes. Once activated astrocytes upregulate the production of various molecules, including matrix metalloproteinases (MMP’s), nitric oxide synthase-2 (NOS-2), tumor necrosis factor- alpha (TNF- α), and Endothelin, thereby creating an altered microenvironment leading to tissue remodelling and axonal damage. Mechanical stress leads to stimulation of EGFR which, in turn, leads to activation of astrocytes and thereby to an upregulation of NOS-2. Blockage of EGFR, by a tyrosine kinase inhibitor therefore prevents the activation of astrocytes [5]. Interestingly, such a treatment not only inhibits the activation of astrocytes but also leads to a reduction of loss of retinal ganglion cells. This indirectly indicates that the activation of astrocytes is relevant in GON [2, 3, 6]. Whether this approach will lead to glaucoma treatment in humans can at the moment not be predicted.

- Inhibition of the effect of Endothelin-1 improves ocular blood flow

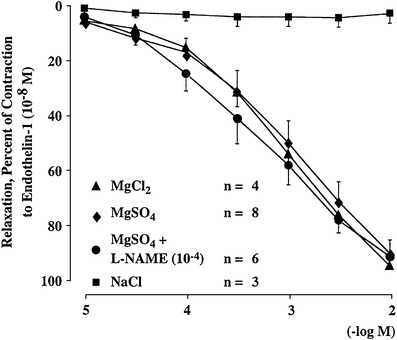

In glaucoma patients plasma concentration of Endothelin-1(EN-1) is increased [7]. Endothelin not only further reduces optic nerve head blood flow and impairs anterograde and retrograde axoplasmatic transport [8, 9], but also activates astrocytes [10]. This is further supported by the fact that patients with a vascular dysregulation more often have activated retinal astrocytes which can be visualised clinically [11, 12]. The effect of Endothelin can be partially blocked by a number of different drugs such as calcium channel blockers (CCB’s) including magnesium (a physiological CCB (Fig. 3)), dipyrimadole or Endothelin blockers [13–16]. Whether an inhibition of Endothelin indeed also inhibits the activation of astrocytes has not yet been studied.

- Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS-2) decreases damage

Nitric oxide (NO), also known as the “endothelium-derived relaxing factor”, is biosynthesised from arginine and oxygen by various nitric oxide synthase (NOS) enzymes. There are three basic forms of NOS: Neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS or NOS-1), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS or NOS-2) and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS or NOS-3).

Nitric oxide synthase -2 (NOS-2), leads to a marked production of nitric oxide. NOS-2 can be inhibited by the drug aminoguanidine, a nucleophilic hydrazine compound. Aminoguanidine is an oral insulin stimulant for type 2 diabetes mellitus. It further seems to prevent the formation of advanced glycation end products [17]. In addition, it is a relative specific inhibitor of NOS-2 which is why it was studied in experimental glaucoma. In experimental glaucoma aminoguanidine was capable of preventing the development of GON [18]. Such treatment appears very promising but clinical studies are not yet available.

Reduction of severe hypotension improves prognosis

Fig. 3.

Magnesium inhibits the effect of endothelin-1 (ET-1). Relaxing effect of increasing concentrations of MgSO4 and MgCl2 added to endothelial-precontracted porcine ciliary arteries (−10−8 M). NaCl, which has the same osmolarity as MgSO4, did not evoke a relaxation

Low blood pressure as well as nocturnal over dipping increases the probability of visual field deterioration [19, 20]. We can therefore assume that an increase in blood pressure in patients with hypotension may improve prognosis although interventional studies supporting this view are rare. Treatment of hypotension with vasoconstrictive drugs although increasing blood pressure may further reduce blood flow. Blood pressure, however, can be increased with an increase in salt intake (1–5 g daily) [21]. In severe cases the intake of the low–dosed fludrocortisone, (0.1 mg/2x per week) has been described [22]. Fludrocortisone treatment not only slightly increases blood pressure and reduces nocturnal dips but also improves the regulation of blood flow indirectly [22].

Improvement of vascular regulation (autoregulation) stabilises oxygen supply

Vascular dysregulation is a major risk factor for GON [23].Vascular regulation can be improved by various drugs. Among the IOP lowering drugs, only carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (in particular dorzolamide), have proven to both increase ocular blood flow (OBF) and improve the regulation of OBF [24], thereby decreasing the chance of reperfusion injury [25].

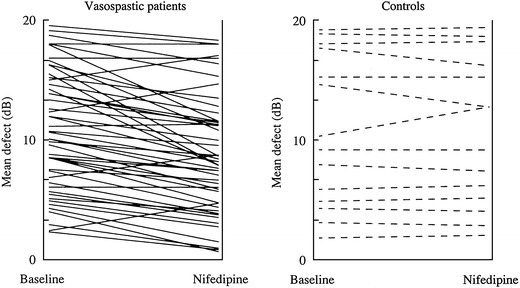

Parallel to an improvement in OBF, an improvement in visual field was observed (Fig. 4). Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAI), like acetazolamide, improve visual fields in glaucoma patients [26–28]. Similar effects have been observed for calcium channel blockers (CCB’s). An improvement in OBF and visual function was only observed in patients with a vascular dysregulation [29]. Accordingly, a positive response to OBF on carbon-dioxide breathing predicts the effect of CCB’s on OBF [30]. The effect of CCB’s on visual field have also been demonstrated in masked double blind studies [31]. Likewise, CCB’s decreased the OBF reducing effect of an Endothelin infusion in healthy volunteers [32]. Dipyridamol, a drug often used in the past as a platelet inhibitor, also inhibits the effect of Endothelin [33], and improves OBF [34]. Unfortunately the long-term role of dipyrimadole on glaucoma patients has not yet been studied. Among the systemic treatments, magnesium is a weak but harmless drug that inhibits the effect of Endothelin partially [13] and improves OBF [15].

Fig. 4.

Short-term effect of nifedipine. Mean defect of visual field test (Octopus program G1) at baseline and 60 min after intake of 20 mg sustained- release nifedipine in a) improvement in patients with digital vasospasm, and b) no change in patients without digital vasospasm. When treatment was continued for 12 months, the improvement in the group with vasospasm was still detectable (not shown here)

Omega-3-fatty acids (Omega 3-FA’s) have a number of different effects including the modulation of intracellular calcium ion release and thereby the stabilisation of circulation [35]. Omega 3-FA’s also increase the production of uncoupling proteins and thereby improve ATP independent heat production which is most probably impaired in patients with vascular dysregulation [36, 37].

Cacao beans from the seed of Theobroma Cacao contain a subclass of flavonoids, flavan-3-ols, which have been reported to augment endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), and thereby nitric oxide (NO). This improves endothelium dependent vasorelaxation [38]. Unfortunately the use of cacoa beans has not yet been studied in the context of glaucoma.

Reduction of oxidative stress improves prognosis

Free radicals are involved in a number of inflammatory and degenerative diseases. Accordingly, oxidative stress is involved in the pathogenesis of GON where free radicals cause a damage to retinal ganglion cells and their axons [39, 40]. In addition, oxidative stress leads to degeneration of trabecular meshwork (TM) [41, 42] and thereby alterations in the aqueous outflow pathway (Fig. 5), leading to increased IOP which, in turn, also damages retinal ganglion cells. The target of oxidative stress relevant in the development of GON are most probably the mitochondria [43]. It is therefore desirable to have a drug protecting the mitochondria, in particular the mitochondria of the optic nerve head [43]. This can unfortunately not be achieved by an increase intake of vitamins such as vitamin C or vitamin E. Only molecules reaching the inner membrane of the mitochondria can be of potential use. Ginkgo contains a number of substances, including polyphenolic flavonoids, that have been proven to protect the mitochondria from oxidative stress and thereby protect the retinal ganglion cells [44–47]. Moreover, ginkgo has been shown to improve visual fields in a long term double masked placebo-controlled study [48]. Efficacy and safety reports have suggested a daily dose of 120 mg to be sufficient and acceptable [49].

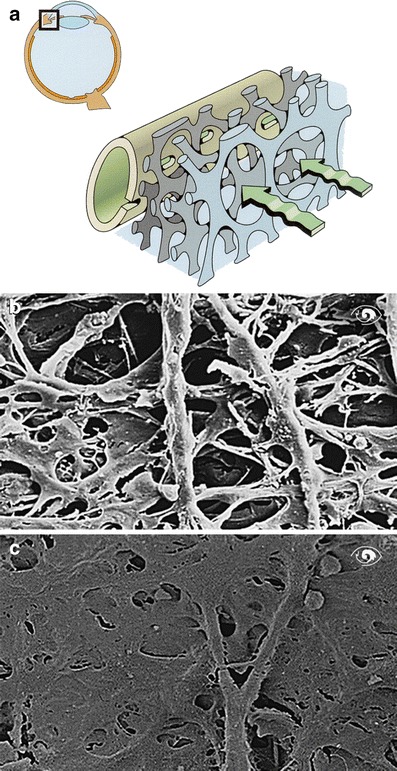

Fig. 5.

a Drainage of aqueous humor. Aqueous humor (green) drains through the trabecular meshwork into Schlemm’s canal. b Trabecular meshwork of a healthy individual. c Trabecular meshwork of a glaucoma patient

There are a number of other naturally occurring substances that could theoretically be beneficial but have not been studied for glaucoma [50–52]. Polyphenolic flavonoids have strong antioxidant capacity due to their free radical scavenging properties. Both green and black tea, are rich sources of flavonoids such as catechin (C), epicatechin (EC), epigallocatechin (EGC) [53, 54]. Coffee also has good antioxidant properties due to polyphenolic compounds. In addition, coffee contains the molecule 3-methyl-1,2-cyclopentanedione (MCP) which has been shown to be a selective scavenger of the peroxynitrite [55]. Other naturally occurring compounds containing polyphenols include dark chocolate [56] and red wine [57].

Anthocyanins, rich in foods such as bilberry, are another class of substances with antioxidant properties. In addition to polyphenolic rings, anthocyanins possess a positively charged oxygen atom in their central ring which enables them to readily scavenge electrons [58].

Ubiquinone, Coenzyme Q 10, is a coenzyme for the inner mitochondrial enzyme complexes involved in energy production within the cell with strong antioxidant properties. Coenzyme Q10 has been demonstrated to prevent lipid peroxidation and DNA damage induced by oxidative stress [59]. Ubiquinone has been studied well in dermatology but unfortunately studies of its use in glaucoma are lacking and therefore currently limit the use of this agent.

Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxyryptamine) is an indoleamine, secreted by the pineal gland, which exerts antioxidant properties. Melatonin has been shown to neutralise free radicals [60]. In the retina, melatonin reduces the elevation of cGMP by suppressing nitric oxide synthase (NOS) activity and thereby levels of nitric oxide (NO) indicating a neuroprotective role. In addition, melatonin stimulates a number of antioxidative enzymes [61].

Inhibition of metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) reduces retinal ganglion loss and tissue remodelling

MMP-2 and MMP-9 are upregulated in astrocytes of glaucoma patients [62]. MMP-9 is also upregulated in the circulating lymphocytes of glaucoma patients [63]. These MMP’s, in particular MMP-9, are involved in both retinal ganglion cell loss and in tissue remodelling. MMP-9 can be inhibited pharmacologically by GM6001, also known as Ilomastat (N-[(2R)-2-(hydroxamidocarbonylmethyl)-4-methylpentanoyl]-L-tryptophan methylamide). Studies reveal that inhibition of MMP-9 with GM6001 prevents retinal ganglion cell loss in an animal model [64]. Moreover, MMP-9 knock out mice do not show apoptosis of retinal ganglion cells even when the optic nerve is ligated [65]. MMP-9 most probably plays a role in the pathogenesis of GON.

Stimulation of heat shock protein production (HSP) protects proteins

Heat shock proteins (HSP’s) are produced by different cells when subjected to stress (e.g. elevated temperatures or oxidative stress). The upregulation of these proteins is a protective mechanism as they act as molecular chaperones protecting the three-dimentional structure of other proteins. In a rat model, pharmacologically induced upregulation of HSP’s, by the systemic administration of the compound geranylgeranylacetone (GGA), protected retinal ganglion cells from glaucomatous damage [66]. Whether treatment with this drug or the natural stimulation of HSP’s (eg. by sauna baths) is beneficial in humans, needs to be studied.

Concluding remarks

Predictive medicine is expected to be most effective when applied to multifactorial disease such as glaucoma. We still do not know the exact mechanisms that lead to damage of the trabecular meshwork and thereby to an increase in IOP, nor do we know the exact mechanisms leading to GON . Obviously there are a number of factors and mechanisms involved. The different risk factors known, may finally lead to damage the same or similar pathomechanisms to GON.

Therapeutically, we can either eliminate or mitigate risk factors or target defined pathogenic steps. Risk factors that can be influenced include increased IOP, low blood pressure and vascular dysregulation. Blood pressure dips can be avoided by intake of salt or fludrocortisone [22]. Vascular regulation can be improved locally by carbonic anhydrase inhibitors [24], systemically with magnesium [13, 15] or with low doses of calcium channel blockers [67]. Oxidative stress at the level of mitochondria can be reduced by the intake of gingko biloba [44, 45]. Whether such treatment will be an adjunctive to the conventional IOP-lowering treatment (e.g. in patients with POAG) or whether it shall be used by itself (e.g. in patients with NTG) remains to be seen.

Pathogenic steps that can be targeted include activation of astrocytes, upregulation of NOS-2 or MMP’s. The very different risk factors finally damage the optic nerve head in a very similar fashion. At the moment any type of clinical or experimental treatment is based on the prevention of GON. A restoration of damaged function is at the moment not possible at all. Already, many of these new treatment strategies have proven to be beneficial in humans [68]. For those remaining, further rigorous investigation is deserved to open up a new therapeutic era in glaucoma.

References

- 1.Flammer J, Mozaffarieh M. What is the present pathogenetic concept of glaucomatous optic neuropathy? Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52(Suppl 2):S162–73. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernandez MR, Agapova OA, Yang P, Salvador-Silva M, Ricard CS, Aoi S. Differential gene expression in astrocytes from human normal and glaucomatous optic nerve head analyzed by cDNA microarray. Glia. 2002;38:45–64. doi: 10.1002/glia.10051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang X, Neufeld AH. Activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor in optic nerve astrocytes leads to early and transient induction of cyclooxygenase-2. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2035–41. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hashimoto K, Parker A, Malone P, Gabelt BT, Rasmussen C, Kaufman PS, Hernandez MR. Long-term activation of c-Fos and c-Jun in optic nerve head astrocytes in experimental ocular hypertension in monkeys and after exposure to elevated pressure in vitro. Brain Res. 2005;1054:103–15. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu B, Chen H, Johns TG, Neufeld AH. Epidermal growth factor receptor activation: an upstream signal for transition of quiescent astrocytes into reactive astrocytes after neural injury. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7532–40. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1004-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neufeld AH, Liu B. Glaucomatous optic neuropathy: when glia misbehave. Neuroscientist. 2003;9:485–95. doi: 10.1177/1073858403253460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emre M, Orgul S, Haufschild T, Shaw SG, Flammer J. Increased plasma endothelin-1 levels in patients with progressive open angle glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:60–3. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.046755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stokely ME, Yorio T, King MA. Endothelin-1 modulates anterograde fast axonal transport in the central nervous system. J Neurosci Res. 2005;79:598–607. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taniguchi T, Shimazawa M, Sasaoka M, Shimazaki A, Hara H. Endothelin-1 impairs retrograde axonal transport and leads to axonal injury in rat optic nerve. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2006;3:81–8. doi: 10.2174/156720206776875867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prasanna G, Krishnamoorthy R, Clark AF, Wordinger RJ, Yorio T. Human optic nerve head astrocytes as a target for endothelin-1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:2704–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grieshaber MC, Terhorst T, Flammer J. The pathogenesis of optic disc splinter haemorrhages: a new hypothesis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84:62–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2005.00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grieshaber MC, Orgul S, Schoetzau A, Flammer J. Relationship between retinal glial cell activation in glaucoma and vascular dysregulation. J Glaucoma. 2007;16:215–9. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31802d045a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dettmann ES, Luscher TF, Flammer J, Haefliger IO. Modulation of endothelin-1-induced contractions by magnesium/calcium in porcine ciliary arteries. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1998;236:47–51. doi: 10.1007/s004170050041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaspar AZ, Flammer J, Hendrickson P. Influence of nifedipine on the visual fields of patients with optic-nerve-head diseases. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1994;4:24–8. doi: 10.1177/112067219400400105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaspar AZ, Gasser P, Flammer J. The influence of magnesium on visual field and peripheral vasospasm in glaucoma. Ophthalmologica. 1995;209:11–3. doi: 10.1159/000310566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gasser P, Flammer J. Short- and long-term effect of nifedipine on the visual field in patients with presumed vasospasm. J Int Med Res. 1990;18:334–9. doi: 10.1177/030006059001800411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brownlee M, Vlassara H, Kooney A, Ulrich P, Cerami A. Aminoguanidine prevents diabetes-induced arterial wall protein cross-linking. Science. 1986;232:1629–32. doi: 10.1126/science.3487117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neufeld AH, Sawada A, Becker B. Inhibition of nitric-oxide synthase 2 by aminoguanidine provides neuroprotection of retinal ganglion cells in a rat model of chronic glaucoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9944–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaiser HJ, Flammer J. Systemic hypotension: a risk factor for glaucomatous damage? Ophthalmologica. 1991;203:105–8. doi: 10.1159/000310234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tokunaga T, Kashiwagi K, Tsumura T, Taguchi K, Tsukahara S. Association between nocturnal blood pressure reduction and progression of visual field defect in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma or normal-tension glaucoma. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2004;48:380–5. doi: 10.1007/s10384-003-0071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pechere-Bertschi A, Nussberger J, Biollaz J, Fahti M, Grouzmann E, Morgan T, Brunner HR, Burnier M. Circadian variations of renal sodium handling in patients with orthostatic hypotension. Kidney Int. 1998;54:1276–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gugleta K, Orgul S, Stumpfig D, Dubler B, Flammer J. Fludrocortisone in the treatment of systemic hypotension in primary open-angle glaucoma patients. Int Ophthalmol. 1999;23:25–30. doi: 10.1023/A:1006434231844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flammer J, Haefliger IO, Orgul S, Resink T. Vascular dysregulation: a principal risk factor for glaucomatous damage? J Glaucoma. 1999;8:212–9. doi: 10.1097/00061198-199906000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagel E, Vilser W, Lanzl I. Dorzolamide influences the autoregulation of major retinal vessels caused by artificial intraocular pressure elevation in patients with POAG: a clinical study. Curr Eye Res. 2005;30:129–37. doi: 10.1080/02713680490904133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flammer J, Orgul S, Costa VP, Orzalesi N, Krieglstein GK, Serra LM, Renard JP, Stefansson E. The impact of ocular blood flow in glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2002;21:359–93. doi: 10.1016/S1350-9462(02)00008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flammer J, Drance SM. Reversibility of a glaucomatous visual field defect after acetazolamide therapy. Can J Ophthalmol. 1983;18:139–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flammer J, Drance SM. Effect of acetazolamide on the differential threshold. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101:1378–80. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1983.01040020380007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paterson G. Effect of intravenous acetazolamide on relative arcuate scotomas and visual field in glaucoma simplex. Proc R Soc Med. 1970;63:865–9. doi: 10.1177/003591577006300902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guthauser U, Flammer J, Mahler F. The relationship between digital and ocular vasospasm. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1988;226:224–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02181185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pillunat LE, Lang GK, Harris A. The visual response to increased ocular blood flow in normal pressure glaucoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 1994;38(Suppl):S139–47. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(94)90058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitazawa Y, Shirai H, Go FJ. The effect of Ca2(+) -antagonist on visual field in low-tension glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1989;227:408–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02172889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strenn K, Matulla B, Wolzt M, Findl O, Bekes MC, Lamsfuss U, Graselli U, Rainer G, Menapace R, Eichler HG, Schmetterer L. Reversal of endothelin-1-induced ocular hemodynamic effects by low-dose nifedipine in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;63:54–63. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer P, Flammer J, Luscher TF. Effect of dipyridamole on vascular responses of porcine ciliary arteries. Curr Eye Res. 1996;15:387–93. doi: 10.3109/02713689608995829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaiser HJ, Stumpfig D, Flammer J. Short-term effect of dipyridamole on blood flow velocities in the extraocular vessels. Int Ophthalmol. 1995;19:355–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00130854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Engler MB. Vascular relaxation to omega-3 fatty acids: comparison to sodium nitroprusside, nitroglycerin, papaverine, and D600. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 1992;6:605–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00052562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cha SH, Fukushima A, Sakuma K, Kagawa Y. Chronic docosahexaenoic acid intake enhances expression of the gene for uncoupling protein 3 and affects pleiotropic mRNA levels in skeletal muscle of aged C57BL/6NJcl mice. J Nutr. 2001;131:2636–42. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.10.2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hun CS, Hasegawa K, Kawabata T, Kato M, Shimokawa T, Kagawa Y. Increased uncoupling protein2 mRNA in white adipose tissue, and decrease in leptin, visceral fat, blood glucose, and cholesterol in KK-Ay mice fed with eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids in addition to linolenic acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;259:85–90. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karim M, McCormick K, Kappagoda CT. Effects of cocoa extracts on endothelium-dependent relaxation. J Nutr. 2000;130:2105S–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.8.2105S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flammer J. Glaucomatous optic neuropathy: a reperfusion injury. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 2001;218:290–1. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-15883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tezel G. Oxidative stress in glaucomatous neurodegeneration: mechanisms and consequences. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2006;25:490–513. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sacca SC, Pascotto A, Camicione P, Capris P, Izzotti A. Oxidative DNA damage in the human trabecular meshwork: clinical correlation in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:458–63. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.4.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tamm ER, Russell P, Johnson DH, Piatigorsky J. Human and monkey trabecular meshwork accumulate alpha B-crystallin in response to heat shock and oxidative stress. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:2402–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abu-Amero KK, Morales J, Bosley TM. Mitochondrial abnormalities in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2533–41. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eckert A, Keil U, Kressmann S, Schindowski K, Leutner S, Leutz S, Muller WE. Effects of EGb 761 Ginkgo biloba extract on mitochondrial function and oxidative stress. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003;36(Suppl 1):S15–23. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eckert A, Keil U, Scherping I, Hauptmann S, Muller WE. Stabilization of mitochondrial membrane potential and improvement of neuronal energy metabolism by Ginkgo Biloba Extract EGb 761. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1056:474–85. doi: 10.1196/annals.1352.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ritch R. Potential role for Ginkgo biloba extract in the treatment of glaucoma. Med Hypotheses. 2000;54:221–35. doi: 10.1054/mehy.1999.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sener G, Sener E, Sehirli O, Ogunc AV, Cetinel S, Gedik N, Sakarcan A. Ginkgo biloba extract ameliorates ischemia reperfusion-induced renal injury in rats. Pharmacol Res. 2005;52:216–22. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quaranta L, Bettelli S, Uva MG, Semeraro F, Turano R, Gandolfo E. Effect of Ginkgo biloba extract on preexisting visual field damage in normal tension glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:359–62. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01745-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bars PL, Kastelan J. Efficacy and safety of a Ginkgo biloba extract. Public Health Nutr. 2000;3:495–9. doi: 10.1017/s1368980000000574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mozaffarieh M, Grieshaber MC, Orgul S, Flammer J. The potential value of natural antioxidative treatment in glaucoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53:479–505. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mozaffarieh M, Flammer J. A novel perspective on natural therapeutic approaches in glaucoma therapy. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2007;12:195–8. doi: 10.1517/14728214.12.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mozaffarieh M, Flammer J. Is there more to glaucoma treatment than lowering IOP? Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52(Suppl 2):S174–9. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramassamy C. Emerging role of polyphenolic compounds in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases: a review of their intracellular targets. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;545:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wei H, Zhang X, Zhao JF, Wang ZY, Bickers D, Lebwohl M. Scavenging of hydrogen peroxide and inhibition of ultraviolet light-induced oxidative DNA damage by aqueous extracts from green and black teas. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26:1427–35. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(99)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim AR, Zou Y, Kim HS, Choi JS, Chang GY, Kim YJ, Chung HY. Selective peroxynitrite scavenging activity of 3-methyl-1, 2-cyclopentanedione from coffee extract. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2002;54:1385–92. doi: 10.1211/002235702760345473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miller KB, Stuart DA, Smith NL, Lee CY, McHale NL, Flanagan JA, Ou B, Hurst WJ. Antioxidant activity and polyphenol and procyanidin contents of selected commercially available cocoa-containing and chocolate products in the United States. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:4062–8. doi: 10.1021/jf060290o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haufschild T, Kaiser HJ, Preisig T, Pruente C, Flammer J. Influence of red wine on visual function and endothelin-1 plasma level in a patient with optic neuritis. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:825–6. doi: 10.1002/ana.10602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maatta-Riihinen KR, Kahkonen MP, Torronen AR, Heinonen IM. Catechins and procyanidins in berries of vaccinium species and their antioxidant activity. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:8485–91. doi: 10.1021/jf050408l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tomasetti M, Alleva R, Borghi B, Collins AR. In vivo supplementation with coenzyme Q10 enhances the recovery of human lymphocytes from oxidative DNA damage. FASEB J. 2001;15:1425–7. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0694fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Allegra M, Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Gentile C, Tesoriere L, Livrea MA. The chemistry of melatonin’s interaction with reactive species. J Pineal Res. 2003;34:1–10. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079X.2003.02112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Siu AW, Maldonado M, Sanchez-Hidalgo M, Tan DX, Reiter RJ. Protective effects of melatonin in experimental free radical-related ocular diseases. J Pineal Res. 2006;40:101–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Agapova OA, Ricard CS, Salvador-Silva M, Hernandez MR. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in human optic nerve head astrocytes. Glia. 2001;33:205–16. doi: 10.1002/1098-1136(200103)33:3<205::AID-GLIA1019>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Golubnitschaja O, Yeghiazaryan K, Liu R, Monkemann H, Leppert D, Schild H, Haefliger IO, Flammer J. Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinases in mononuclear blood cells of normal-tension glaucoma patients. J Glaucoma. 2004;13:66–72. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200402000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Manabe S, Gu Z, Lipton SA. Activation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 via neuronal nitric oxide synthase contributes to NMDA-induced retinal ganglion cell death. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4747–53. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chintala SK, Zhang X, Austin JS, Fini ME. Deficiency in matrix metalloproteinase gelatinase B (MMP-9) protects against retinal ganglion cell death after optic nerve ligation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47461–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ishii Y, Kwong JM, Caprioli J. Retinal ganglion cell protection with geranylgeranylacetone, a heat shock protein inducer, in a rat glaucoma model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:1982–92. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Strenn K, Matulla B, Wolzt M, Findl O, Bekes MC, Lamsfuss U, Graselli U, Rainer G, Menapace R, Eichler HG, Schmetterer L. Reversal of endothelin-1-induced ocular hemodynamic effects by low-dose nifedipine in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;63:54–63. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ritch R. Neuroprotection: is it already applicable to glaucoma therapy? Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2000;11:78–84. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200004000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]