Abstract

The foundation of Germany’s healthcare system is derived from Germany’s Basic Law (Grundgesetz), which obliges the state to provide social services to its citizens (Articles 20, 28 of the Basic Law). Specifically, the state must ensure sufficient, needs-based ambulatory and inpatient medical treatment, in qualitative and quantitative terms, as well as guarantee the provision of medicine. The federal government may assume this duty itself or delegate it to state governments and institutions in the form of service guarantee contracts (§ 72, German Social Insurance Code, Book V). The following paper provides an overview of the structural organization, individual components and funding of the German healthcare system, which, in its current form, is extremely complex and which even experts find difficult to grasp.

Keywords: Germany, Basic Law, Healthcare system, Stakeholders, Government, Insurance

Basic principles of healthcare system

Germany’s healthcare system is a contribution-based social insurance model, whose main features can be traced back to the beginning of the Middle Ages and even earlier. It is an important economic area and, with its large workforce of approximately 4.3 million employees (status in 2007), also plays a key role in labor market policy. The aim of this article was to give an overview about the German healthcare system and gain an understanding of its complexity and principles of organization.

The Germany’s healthcare system is primarily funded by the public sector, which levies the funding in the form of social insurance payments, and covers in particular the costs of state supervision and basic infrastructure (e.g. administrative bodies and ministries, government institutes and facilities, public health offices and medical education). The premiums collected by the public and private health and nursing insurance companies, on the other hand, are employed for direct healthcare services, such as the remuneration of service providers (e.g. physicians, nurses), the cost of medicine, therapies and medical aids as well as equipment. Private households pay deductibles and healthcare expenses such as over-the-counter medicines and services not covered by health insurance. Healthcare services are provided by both public (e.g. federal, state, and municipal government), non-profit organizations (churches and charities, such as Caritas and the German Red Cross) and private institutions (companies and individuals with commercial interests), with non-profit and private healthcare providers providing the bulk of direct services (Table 1).

Table 1.

Funding of the German healthcare system [1]

| 1995 | 2000 | 2007 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total expenditure | 186 474 mln euros | 212 335 mln euros | 252 751 mln euros |

| Public sector | 10.7% | 6.4% | 5.2% |

| SHI insurance | 67.3% | 69.6% | 67.8% |

| Private health/nursing insurance | 7.7% | 8.3% | 9.3% |

| Employer contributions | 4.2% | 4.1% | 4.2% |

| Private households | 10.2% | 11.6% | 13.5% |

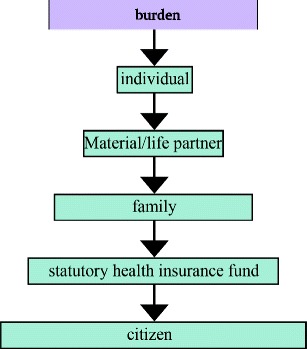

Basic principles of social rights are used as the framework for ensuring social security in cases of illness, and must be followed by both the health insurance companies and health service providers. The principle of the welfare state is based on the Federal Republic of Germany’s Basic Law (Grundgesetz), which specifies that the state must guarantee all citizens social justice and the equal participation in society, including appropriate treatment in case of illness. Individuals with below average earning power or economic resources must receive the same quality and quantity of medical care as others. Thus, overall, the healthcare system is organized around the principle of solidarity (Solidarprinzip), which provides that every member of a supportive society is entitled to assistance from the other members of the society in the case of illness. A main feature of the statutory health insurance scheme is social reconciliation (Solidarausgleich), which is expressed in two main ways: firstly, between the healthy and ill, in that all members – including the healthy – meet the costs of the necessary treatment and benefits if a member falls ill regardless of the individual’s economic resources, including the additional costs of securing the individual’s livelihood, such as continued wages and sickness benefits; and secondly, between high and low incomes, in that up to a defined income threshold, all members of the statutory health insurance pay an income-dependant percentage of their earnings. This solidarity model stands in contrast to the subsidization principle, which provides that an individual’s expenses are only then assumed by the supportive society if the individual is demonstrably overextended. Until such a point, the individual is obliged to contribute to the treatment costs. In the subsidization model, the healthcare expenses are met by a sequence of supportive societies from smallest to largest: the individual, his or her martial or life partner, the family, the statutory health insurance fund, and finally the services the individual is entitled to as a citizen (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The subsidization model [1]

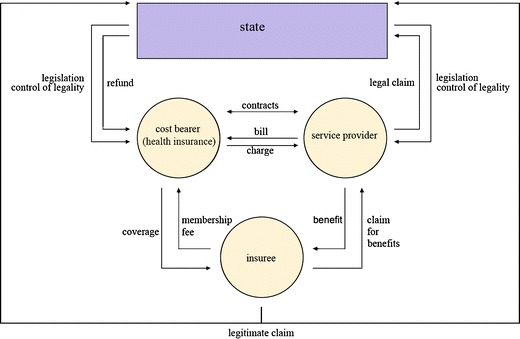

Specifically, the state is obligated according to the Basic Law to provide its citizens with the minimum provisions for a human life with dignity, including adequate medical care that meets the needs of the population (principle of meeting need, Bedarfsdeckungsprinzip), in terms of ambulatory services, inpatient beds, quantitative and qualitative measures, and the dispensing of medical products. This is expressed legally as the service guarantee contract (Sicherstellungsauftrag). However, the federal government does not have to meet this obligation directly, but can delegate the service guarantee contract to state governments and other institutions. In turn, these contractually obligate healthcare providers and facilities to deliver the services. Consequently, on a legal and decision-making level, bodies such as the health insurance companies and associations of statutory health insurance (SHI) physicians function as indirect, outsourced public administration authorities with some measure of self-governance, which take the form of statutory corporations. By thus relieving the burden on the state, they are in turn granted substantial say in health policy, and also represent the interests of their members and implement government regulation. Representatives of the health insurance companies and service providers debate and decide key questions in service provision and remuneration in joint self-administration. For example, the Federal Joint Committee (G-BA), on which physicians, dentists, hospitals, health insurers and patients are represented, has significant influence on which services are provided by the statutory health insurers and under which conditions. Its decisions are binding for both the health insurance companies and SHI service providers. Furthermore, all parties, including the insured, the various associations and the funding bodies, are entitled to legally appeal the decisions reached by the associations and government authorities as part of the service guarantee contract.

While, with the exception of military hospitals, the federal government does not directly fund healthcare facilities, it does maintain a number of healthcare institutes and federal agencies, each with its own areas of responsibility. These include the Robert Koch Institute (disease control and prevention, particularly extremely dangerous or contagious diseases; federal health reporting), the Paul Ehrlich Institute (ensuring drug safety; testing, approval and monitoring of vaccinations, sera and blood products), the German Institute of Medical Documentation and Information (development of medical classifications and medical databases), the German Federal Center for Health Education (development of health education and prevention strategies), the German Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (drug assessment and authorization, monitoring of legal narcotics trade) and the German Federal (Social) Insurance Office. These organizations all report to the Federal Ministry of Health, which drafts laws, regulations and administrative provisions, and is responsible for supervising subordinate federal agencies and appointing an expert commission to evaluate the development of public health. The highest state authorities are the ministries of social affairs or health, to which, in turn, other state authorities, such as the state public health offices, report. The latter ensure compliance with federal and state laws, supervise the institutions under their responsibility, such as municipal health authorities, health and social security insurance companies at state level, the local association of SHI physicians (Kassenärztliche Vereinigung, KV). The states also directly fund healthcare facilities, such as the university clinics and state psychiatric hospitals. Municipalities, as relatively autonomous regional authorities with a guaranteed right to local self-government, enforce the legislation governing healthcare professions, the distribution of foodstuffs and medical products, contagious disease prevention and control and health education and counseling, with the public health offices implementing the various associated measures [1, 5, 7, 9, 10] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The structure of the German healthcare system [1]

(Statutory) Health insurance in Germany

Compulsory health insurance was introduced for all residents in the Federal Republic of Germany on 1st January 2009. Approximately 90% of citizens living in Germany are in the statutory health insurance (SHI) system. A further 9% have private health insurance (PHI), while 2% have company or trade insurance or are uninsured despite legal obligation (<1%). Joining the SHI scheme, as opposed to the private system, is obligatory for individuals, whose income is below a legally specified amount (income threshold in 2009: 4050 euros, assessment threshold: 3675 euros), unless they belong to a mandatory SHI-exempt professional group (see below). Within the SHI system, the insuree can choose between various health insurance companies and has also been free to switch between funds since 1996. At the same time, the statutory health insurance funds are contractually obliged to accept any applicant, regardless of health risk profile.

The minimum healthcare that must be provided by all funds is specified as a list of benefits in Book V of the German Social Insurance Code (SGB), and includes maintaining health standards, healing, health education, counseling on and measures for healthy living conditions. To meet these requirements, the SHI funds have to provide the following services: prevention, early detection and treatment of diseases, medical rehabilitation, contraception, sterilization, abortion and the provision of maternity and sick leave allowances. SHI insurees receive the healthcare services as benefits-in-kind (Sachleistungsprinzip), which are provided by third parties (e.g. physicians, hospitals, pharmacists), who subsequently bill the health insurance company.

SHI expenditure is almost completely covered by premiums (and to a small extent, also by other funding such as federal grants), which are calculated according to earning power, rather than individual health risk profile, as a percentage (currently 14.9%, beginning with January 2011—15.5%) of income subject to premium levy, with employers matching the contribution of the employee. Family members without an income of their own are usually insured free of charge and certain groups of insurees (e.g. low-income earners, students, apprentices) receive a premium reduction. Health premium increases are not only permitted, but also in fact prescribed by law, if expenses increase and can no longer be met by the SHI scheme. Such increases are limited to 1% of income subject to premium levy, whereby an increase of 8 euros a month is permitted without prior assessment of the insuree’s income. The statutory health funds are not permitted to operate on a for-profit basis and excess contributions must be reimbursed to insurees (generally in the form of premium reductions). Deductibles and supplementary charges (such as for prescription medicine) are limited in total to 2% (1% for the chronically ill in ongoing treatment) of the individual’s gross income to avoid disproportionately burdening the individual insuree.

Funding of the SHI scheme is managed by means of a centralized health fund (Gesundheitsfonds) and a morbidity-based risk adjustment scheme (Morbi-RSA). In this system, the health insurance companies are obliged to transfer all premiums, excluding supplementary charges, to the federal bank. Federal grants for health infrastructure are also paid into this fund. The health fund is administrated by the Federal (Social) Insurance Office, which determines how much of the fund will be allocated to each insurance company based on specific criteria, which together comprise the morbidity-based risk adjustment scheme. Features include a uniform monthly basic flat rate (2009: 185 euros) and administrative flat rate (2009: 5 euros) for each insuree, as well as bonuses and deductions based on the individual’s age, sex and illnesses (a selection of 80 groups of diseases are included as factors).

As statutory corporations, the health insurance companies are supervised by the state, without themselves being agencies of the state. They are self-governing. Every 6 years, the premium-paying insurees elect an advisory board to the association of health insurance funds. This board in turn elects a board of directors, which represents the health insurance companies in the public sphere [1, 2].

Private health insurance

Private health insurance (PHI) companies are corporations subject to private law, which operate on a for-profit basis. A little over than half (2008: 47 of a total of 83 PHI companies) are members of the Association of Private Insurers (Verband der privaten Krankenversicherungen e.V.). Private health insurers not in the association are usually ‘supplementary’ funds (which primarily offer additional services, but not full health insurance coverage). The association’s insurance companies can be divided into two groups: mutual insurance associations (these are self-governing and profits are paid to the insurees) and shareholder companies (these are managed on behalf of the shareholders and profits are paid to the shareholders).

Only employees whose regular income is above the insurance threshold, civil servants, clergy, private school teachers, pensioners and the self-employed can choose the private health insurance system over the SHI scheme. A voluntary member of the SHI scheme can only switch to the PHI system if their earnings have been above the compulsory insurance threshold for three consecutive calendar years. Whether a private health insurer accepts the applicant depends primarily on the applicant’s health risk profile, which is assessed for each potential new insuree. Unlike the statutory health insurers, private health insurers do not have a contractual obligation to accept applicants. They can also demand additional risk premiums or exclude particular services from the contract (with limited exceptions). As part of the health risk portfolio process, the applicant has to release physicians and any other involved healthcare workers from their non-disclosure agreements. If the applicant is accepted, the insuree chooses between various services to create a specially tailored benefits package. The premium is calculated based on the individual’s predetermined health risk portfolio, which includes the applicant’s age on joining, state of health on application, gender, as well as the type and extent of the services covered (equivalency principle). If the private health insuree is an employee, the employer pays 50% of the premium, in so far as the sum does not exceed the average SHI premium.

The private health insurer provides the insuree with cash benefits, in the form of reimbursements for medical treatment expenses. The level of these reimbursements depends on the individual insurance contract. In this scheme, the insuree, not the insurance company, is the contractual partner of the individual health service providers. Additionally, unlike the SHI, private insurance funds do not enter into service provision contracts with physicians or hospitals (with a few exceptions). The insuree chooses the service provider and meets the incurred costs, which are later reimbursed by the insurance company (based on the individual contract, either in full or in part). The service provider’s bill usually takes the applicable SHI fee schedule for the service in question (e.g. the physicians’ fee schedule, GOÄ) as its starting point, but can be 3.5 times that of the fee schedule rate, depending on the type of service and the time required. If a (costly) hospital stay is planned, the hospitals are entitled to demand advance payment. To prevent the insurance premiums from increasing too steeply with age and the associated higher expenses, the private insurers charge younger members higher contribution rate than necessary for their age and condition of health (aging provision).

Private health insurers are also obliged to offer specified minimum services, the cost of which may not exceed the corresponding highest SHI rates. For instance, certain insurees, depending on the individual’s age and how long they have been a member, are offered a standard tariff, which includes the same benefits are that offered by the SHI scheme. Since 1st January 2009, new insurees also have a right to a uniformly calculated basic tariff that corresponds to the SHI benefits catalogue. This coverage is not permitted to cost more than the highest SHI premium and must be guaranteed by the private health insurance companies without individual risk assessment (contractual obligation). Additionally, private health insurers are in principle not allowed to terminate contracts that serve to fulfill the obligation of compulsory insurance. However, they are entitled to raise an insuree’s premium if the costs rise (e.g. service and price increases in healthcare, legislature changes), if authorization is first obtained from a state insurance office-appointed fiduciary. If in a calendar year an insuree does not use any medical services, or only to a limited extent, the private health insurer generally reimburses them with up to several months of contribution payments [1, 11, 12] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of statutory and private health insurance funds and insurees in Germany [1]

| 1995 | 2000 | 2007 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statutory health insurances funds | 960 | 420 | 253 |

| SHI insurees | 71,886 mln | 71,252 mln | 70,314 mln |

| Private health insurances funds | 54 | 50 | 49 |

| PHI insurees | 6,994 mln | 7,522 mln | 8,249 mln |

Ambulatory medical treatment in Germany

Almost all outpatient medical treatment in Germany is carried out by registered physicians. These are self-employed in individual or joint practices (joint use of surgery rooms by various independent physicians with their own patient files and separate billing), joint surgeries (several physicians in one surgery, with joint patient files and billing) and medical treatment centers (physician-led, interdisciplinary centers, in which at least two doctors with different medical specialties work, often with other participating health practitioners, such as pharmacists, physiotherapists, medical and rehabilitation technology companies). Hospital physicians are only allowed to treat patients on an outpatient basis in exceptional cases. Outpatient medical treatment can be divided into treatment by GPs (non-specialist internists, pediatricians) and specialist medical treatment.

Importantly, physicians can only bill the statutory health insurance companies for the treatment of SHI patients (approx. 90% of the population) if they have been approved as SHI physicians (approx. 95% of all registered physicians). Without SHI approval, physicians may only treat private patients or SHI patients who choose to pay for the treatment directly. Statutory health insurers only cover the costs of medical treatment of a SHI insuree by a private physician in cases of proven emergency. If listed in the association of SHI physicians’ register of medical practitioners and having received either specialist training or at least 6 years training as a GP, a physician can apply for SHI-approval status. Whether the applicant is approved is decided jointly by representatives of the association of SHI physicians and the statutory health insurance companies. The decision depends primarily on the need for outpatient medical services in the relevant health-planning district and the SHI physician must then maintain their practice in this district. Since 1999, psychotherapists can also apply for the status of SHI-approved physicians, if they are members of the applicable association of statutory health insurance physicians and participate in the SHI fee distribution system (see below).

The SHI physician must be a member of the relevant association of SHI physicians, and as such, must adhere to certain guidelines. These include that the SHI physician has to provide the SHI treatment personally and is not allowed to be have another physician substitute for them for more than 3 months annually. The physician provides treatment, decides whether follow-up visits are necessary, refers patients to other specialist physicians where necessary, initiates hospitalization, prescribes drugs and decides whether home care is required. SHI physicians are subject to the laws governing the profession, the regulations of the federal and state associations of SHI physicians, the Treatment Obligations Ordinance, and are obliged to meet certain regulations regarding the distance between surgery and home residence, maintain regular consultation hours, participate in after-hours emergency rostering, document the work, report to the health insurers and ensure that the treatment provided is sufficient, appropriate and cost-effective and does not exceed the limits of the necessary. If approved to do so by the association of SHI physicians, the SHI physician may employ assistant doctors in training or another physician in the same field of expertise.

Virtually all outpatient medical treatment is financed by the SHI. Other contributors include the private health insurers, private households (including quarterly copayments and deductibles), employers and public funding (e.g. remuneration of medical treatment provided to welfare recipients). Germany’s remuneration system is extremely complex and is based on a number of different systems. The health insurers compensate the SHI-approved treatment of its members as lump sums per insuree, negotiated with and paid to the association of SHI physicians. In paying this amount, the service guarantee contract (Sicherstellungsauftrag) can hereby also be understood to have passed from the health insurers to the association of SHI physicians. Remuneration of the SHI physicians takes the form of a fee distribution system. The SHI physician submits the SHI-approved services to the applicable association of SHI physicians on a quarterly basis. In return, after a multistep auditing process, the association remunerates the physician as a proportion of the lump-sum compensation paid by the health insurer. The compensation is initially paid as a preliminary installment (the physician receives the remaining proportion once all SHI-services in the individual health planning district have been settled). A defined proportion of the lump-sum compensation is assigned to each SHI physician. If the physician exceeds that amount by more than 10%, the excess services are only remunerated by a reduced factor. In addition to the lump-sum compensation, services that the state believes require special promotion (e.g. disease prevention, maternity care) are remunerated separately. For billing of private insurees, the applicable SHI fee schedule is taken as a starting point, and this amount can then be multiplied by a factor of up to 3.5, depending on the type of service and the time required, and are remunerated by the user directly, who is then reimbursed by the health insurance company [1, 2, 7, 9–12] (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Number of SHI physicians [8]

| 1995 | 2000 | 2007 | 2009 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians providing SHI services | 119,939 | 126,832 | 134,172 | 137,416 |

| Number of SHI physicians | 17,235 | 114,491 | 120,232 | 121,128 |

Table 4.

GP vs. specialist SHI physicians in Germany in 2009 [8]

| Registered SHI physicians | Medical treatment | Proportion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPs | Specialists | GPs | Specialists | |

| 121,128 | 57,631 | 63,497 | 47.6% | 52.4% |

Associations of SHI physicians

The associations of SHI physicians (17 in total) assume state duties as statutory corporations, but at the same time also represent the interests of the SHI physicians. Each association elects a representative assembly, whose responsibility it is to define the statutes, appoint representatives from their body for the joint self-administration commissions of the physicians and health insurers, and to elect a full-time board of directors every 6 years. This board represents the association in the public sphere and concludes contracts and agreements that are binding for all SHI physicians. The association’s obligations include ensuring sufficient outpatient treatment (quantitatively and qualitatively, including outside of regular consulting hours). To meet this obligation, the association draws up a consumption plan. A new medical practice is only possible if the density of medical services within the health-planning district is less than 110%. If the number of physicians in a particular specialist area exceeds the set threshold set for the planning zone by more than 10%, the planning district is flagged as oversupplied and restrictions on the approval of new service providers are set. In this case, new physicians can only practice in the district by joining existing surgeries or practices, either by taking the practice over or by forming a joint practice. If a planning district is undersupplied, the associations of SHI physicians are obliged to take appropriate counter-measures by motivating physicians to open surgeries in these areas (e.g. by means of financial bonuses, low-interest loans and/or guaranteed minimum turnover volume). The association has a duty to the health insurers to ensure that the SHI-approved treatment fulfills the contractual requirements.

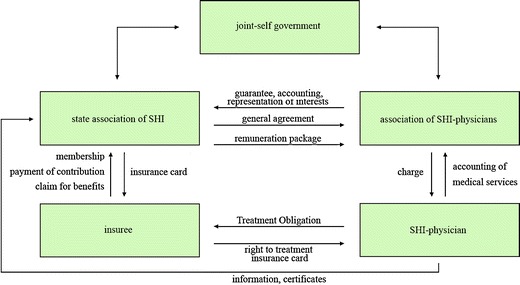

Cooperation in the form of joint self-administration with health insurers is compulsory for the associations. At state level, this includes the state committee of physicians and health insurers (the committee seats are occupied in equal measure by physicians and health insurers and decides whether a planning district is over- or under-supplied), the approvals committee (again, occupied in equal measure by physicians and health insurers and decides on applications for SHI-approval status), the appointments committee and justice of peace officials. These self-administration committees report to the state. An additional responsibility of the association is representing the economic and professional interests of the SHI physicians. This includes negotiating contracts and remuneration packages with the state health insurance associations. In this way, the association has significant influence on the general conditions of the medical care provided by SHI physicians. One of the association’s key duties is negotiating and distributing the lump sum medical service compensation discussed above. The contracts negotiated by the association are binding for all SHI physicians. The associations also represent the interests of the SHI physicians in the public sphere and have input in important health policy decisions at state level. At federal level, the Federal Association of SHI physicians (KBV) assume this responsibility. It issues uniform federal guidelines, works together with the Federal Joint Committee, maintains the federal physicians’ register and lobbies the federal government on behalf of SHI physicians. The federal association also has a representative assembly and a full-time board. Both the state and federal associations are financed by member contributions, which are deducted by the associations for each SHI physician from the lump sum compensation paid by the health insurers [1, 2, 7, 9, 10].

Medical associations

In contrast to the associations of SHI physicians, medical associations (17 in total) focus on the regulation of the professional practice. They specify the rights and duties of physicians in a professional code of conduct, and define continuing education requirements for specialist training. Additionally, the medical associations enforce compliance with professional duties and form commissions that address various issues, including a mediation commission, expert commissions (for medical malpractice) and review boards (to evaluate research proposals). These associations are also statutory corporations under state law and all physicians (not just the SHI physicians) must be members of a medical association, even after retirement. Medical association members elect representative assembly delegates, who, in turn, elect a board of directors. At federal level, the medical associations are merged in the German Medical Association (Bundesärztekammer, BÄK). The federal association’s primary tasks include a coordinating role for the state medical associations, the organization of networking events and structures, ensuring the uniformity of professional and continuing training guidelines, representing the medical profession in the public sphere and lobbying at policy level [1, 2, 9, 10] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Ambulatory medical treatment in Germany [1]

Hospital medical treatment in Germany

The hospital funding law (Krankenhausfinanzierungsgesetz, KHG) defines hospitals as institutions for the diagnosis, curing or alleviation of diseases, ailments or physical injury and the performance of obstetrics by physician or nurses, in which the patients can be provided with room and board. Hospitals approved to treat SHI insurees must fulfill additional requirements. For instance, the hospitals have to a) be under the continual medical management of physicians, b) have sufficient diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities to meet the terms of the hospital provision contract, c) work according to scientifically recognized methods, d) which can be applied by around-the-clock medical, nursing, support and technical staff, e) to diagnose, cure, arrest and alleviate illness or provide obstetrics, primarily through physician and nursing care, f) and which can provide patients with room and board. Rehabilitation centers and similar, specialized inpatient facilities are not considered hospitals. Hospitals are divided into general and other hospitals (hospitals with only psychiatric and/or neurological beds, and purely day or night clinics, in which patients are treated as partial inpatients). Depending on the funding body, the hospitals are public (local district, state, federal government or statutory corporation hospitals), non-profit (the funding bodies have religious, humanitarian or social goals) or private (the funding body has commercial goals, e.g. Belegkrankenhäuser, which are smaller hospitals, in which physicians can, unlike in other hospitals, treat patients on both an outpatient and inpatient basis). Each hospital has physician, nursing and business administration teams, which are headed by a medical director, director of nursing, business director, respectively, who together comprise the hospital management. Some hospitals employ a chief executive officer, who carries the overall responsibility for the hospital. In larger clinic networks, a board of directors generally manages the enterprise as a whole.

Even though some states delegate the service guarantee contract to municipalities, the responsibility for adequate hospital care remains that of the state in the final instance. The states are obliged to assess the need for services within their district in a process known as hospital planning. Hospital planning is based, on the one hand, on a needs assessment of the current and projected requirement for hospital services, and, on the other hand, on an evaluation of whether the existing staffing and infrastructure can be expected to meet the identified need for services. The process and criteria must comply with the regulations of the hospital law and the applicable state hospital law. If the existing provisions do not meet the requirements, additional hospitals are included in the needs assessment. Hospital planning comprises two main components: the hospital plan itself (which specifies all suitable hospitals necessary for providing adequate and sufficient care) and an investment program. The state authorities responsible for the hospital planning and the investment program are the social security or health ministries. Once a hospital is included in the hospital plan, it is SHI-approved and obliged to provide treatment to SHI insurees (in the case of university clinics, registration in the university directory is considered equivalent). In return for assuming responsibility for the service guarantee contract, the SHI-approved hospitals have a right to remuneration from the health insurance companies for the services provided, as well as public investment funding from the state government.

The hospital system is funded by two main sources: health insurance premiums (which cover the hospital’s ongoing operating costs) and tax funds (which cover investment expenditure). Small and medium investments, such as the replacement of furnishings, are covered by lump-sum grants and each hospital in the hospital plan has a legal entitlement to such funding. In contrast, hospitals must apply to the government for funding of larger investment measures, such as new buildings or renovation. Hospitals do not have a guaranteed right to large investment funding. Instead, funding is decided based on the budgetary situation. The health insurers are contractually obliged to negotiate a budget and a nursing care allowance with each hospital in the hospital plan. Each of these hospitals has the right to a customized budget, negotiated with the health insurers (individualism principle) and is generally negotiated as a lump-sum for the following calendar year. Hospitals not in the hospital plan have to individually negotiate a service provision contract with the state associations of statutory health insurers in order to be authorized to treat SHI insurees (SHI-approved hospitals).

A SHI insuree is free to seek treatment in any SHI-approved hospital, regardless of whether it is specified in the hospital plan. Except in emergencies, the patient requires a hospital referral from a registered SHI physician. In both cases, the attending hospital physician decides whether an inpatient stay is necessary. Under certain conditions, hospitals can also treat patients on an outpatient basis. Only specially authorized hospital physicians are permitted to carry out such ambulatory treatment and the authorization is granted by the approval committee of the applicable association of SHI physicians (for a limited, renewable term). A prerequisite is that adequate treatment is only possible if the hospital physician in question is authorized to provide outpatient treatment. An exception is the university outpatient centers of the university hospitals; these have general and unlimited permission to provide treatment on an outpatient basis. Outpatient operations and highly specialized services for rare diseases and illnesses with special illness progression, listed in the service catalogue according to Book V of the German Social Insurance Code, are also approved for ambulatory treatment. Additionally, in medical care centers (Medizinische Versorgungszentren, MVZ), which are interdisciplinary, physician-managed institutions, physicians may work on an employee basis or as self-employed SHI-approved medical professionals. While hospital physicians usually carry out the hospital treatment, general practitioners, if SHI-approved and with special authorization from the association of SHI physicians, can also treat patients on an inpatient basis—a provision that is limited to hospitals or hospital capacity also authorized for this purpose. This inpatient treatment is remunerated from the overall compensation package for outpatient medical treatment, while the hospital expenses are charged to the patient or health insurance company in a separate billing procedure.

The hospital system has a joint self-administration structure. Unlike the outpatient treatment system, this self-administration authority is an association subject to private law and not a statutory corporation. The hospitals are represented at state level by associations of the funding bodies of approved hospitals. In joint self-administration with the state associations of the SHI and the private health insurers, they reach framework decisions for the negotiation of overall budgets and the daily rate for patient care, as well as for hospital planning. At federal level, the German Hospital Association (Deutsche Krankenhausgesellschaft, DKG) works together with the SHI and private health insurance companies’ umbrella associations, also in joint self-governance. Their role is declaring joint recommendations (including for the state-wide average cost of cases, a value that is agreed on annually and on which the fee schedule of hospital treatment is based).

A further task of the hospital association is the ongoing development of the DRG (diagnosis-related groups) patient classification system, in which a certain total of patients are divided into case groups based primarily on medical criteria. Primary and secondary diagnoses, and the medical services corresponding to the diagnoses, comprise the most important distinguishing criteria. Other relevant factors include the reason for referral, age, sex, weight at time of intake (for infants), number of hours of artificial respiration, duration of hospitalization and reason for discharge. Using case-based lump-sums, all general hospital services for a defined case type are remunerated at the same rate for both SHI and private health insurance members, regardless of the actual costs and duration of hospitalization. The DRG system has been binding for all hospitals, except for psychiatry, psychosomatic and psychotherapy (here hospital departmental rates apply) since 1st January 2004. A DRG institute—the Institute for the Hospital Remuneration System (Institut für das Entgeltsystem im Krankenhaus, InEK)—was established, whose duties include performing the calculations and adjustment of the case group system required for the annual negotiation of remuneration rates [1, 2, 4] (Tables 5 and 6).

Table 5.

Number of hospitals and hospital beds [8]

| 1995 | 2000 | 2008 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitals | 2,325 | 2,242 | 2,083 |

| Hospital beds | 609,123 | 559,651 | 503,360 |

Table 6.

The 10 most frequent inpatient diagnoses in Germany in 2008 [6]

| Women | Men | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Live births according to place of birth | 240,513 | Mental and behavioral disorders due to alcohol | 245,971 |

| 2 | Heart failure | 186,090 | Live births according to place of birth | 241,649 |

| 3 | Malignant neoplasm of the breast [mammary] | 149,919 | Angina pectoris | 169,917 |

| 4 | Cholelithiasis | 137,761 | Heart failure | 164,620 |

| 5 | Essential (primary) hypertension | 133,470 | Hernia inguinalis | 150,612 |

| 6 | Gonarthrosis [knee osteoarthritis] | 131,602 | Chronic ischemic heart disease | 143,728 |

| 7 | Stroke | 113,600 | Acute myocardial infarction | 133,635 |

| 8 | Femur fracture | 112,691 | Malignant neoplasm of lung and bronchus | 129,637 |

| 9 | Perineal tear during birth | 109,843 | Cerebral injury | 126,348 |

| 10 | Atrial flutter and fibrillation | 105,008 | Atrial flutter and fibrillation | 113,833 |

Nursing insurance in Germany

Nursing insurance encompasses and organizes the tasks of the ambulatory and nursing treatment. The main task (service guarantee contract) is ensuring insurees receive sufficient, uniform nursing care that meets the recognized standards of medical nursing care. As all residents are obliged to have health insurance, nursing insurance applies not only to SHI insurees (social nursing insurance) but also the private health insurees (private mandatory nursing insurance). Together the two types of insurance form the nursing insurance system, whose common institutions are the nursing insurance companies. Although integrated in and administrated by the health insurance companies, the funds of the nursing and health insurance companies are managed in strict separation. Nursing insurers are required to negotiate service provision contracts with the funding bodies of nursing facilities. The contracts must specify the type, content and extent of the general nursing services, which the nursing facility is obliged to provide and for which it is entitled to receive remuneration from the nursing insurers (contracted nursing institutes are also entitled to state investment funding). The nursing facility has to meet certain requirements to enter into a service provision contract. For instance, the nursing facilities (ambulatory, partial inpatient, or full inpatient) must be managed by a qualified nursing specialist, guarantee performance-oriented and cost-efficient nursing care, have a proven in-house quality management system and meet specified staffing prerequisites. Additionally, every nursing facility has to conclude a nursing contract with each nursing recipient. Once the service provision contract has been concluded, the insurers remunerate facilities directly. In return, the insuree receives benefits-in-kind in the form of nursing and domestic services from the nursing facilities or a nursing care allowance (a combination of services and cash is also possible). Regardless of whether a nursing allowance or non-cash services are provided, persons requiring care are entitled to the provision of nursing and technical aids (e.g. wheelchairs and catheters), as well as additional funds to improve the individual environment and to participation in free nursing courses. If a nursing allowance is provided, the person requiring nursing care is obliged to participate in a nursing consultation every six (care classification I/II) or 3 months (care classification III). The consultation is carried out in the person’s home, identifies possible improvements, and allows the insurers to monitor and secure the quality of the nursing care provided. Furthermore, the Medical Review Board of the Statutory Health Insurance Funds (Medizinischer Dienst der Krankenversicherung, MDK), an institution of the health and nursing insurance companies, also conducts external quality monitoring, whereby homes can be visited by appointment, care facilities without appointment, documents can be viewed, and persons requiring care, family members and staff can be questioned. If the terms of the contract are (repeatedly) violated, the service provision contract can be cancelled by the nursing insurer with immediate effect. The results of inpatient quality monitoring are also publicized.

Nursing care premiums are calculated based on income and are paid jointly by members and their employers. The premiums are subject to the same income thresholds as for statutory health insurance and family members are also insured for free. Nursing care insurance is not designed to comprehensively cover all necessary nursing care needs, but simply ensures basic nursing and home care. Although, like the SHI system, the social nursing insurance system is also managed by a self-administrated public corporation, it cannot determine its own premiums, and is subject to a set rate (currently 1.95%). Thus, the emphasis is on keeping premiums stable and any increase in costs in one area results in a reduction of services elsewhere. The nursing insurance system employs a system of general revenue and cost sharing, which is implemented by the German Federal (Social) Insurance Office. Here, the nursing care insurers determine their monthly turnover, including operating costs and reserve funds and transfer any excess funds in full to a revenue sharing fund set up by the insurance office. On the other hand, if expenditure is higher than the incoming funds, the nursing insurance company is paid the difference from the revenue sharing fund.

Another difference to the SHI system is that an applicant’s need for nursing care is not decided by an independent physician, but by the Medical Review Board of the Statutory Health Insurance Funds. The person requiring nursing care submits an application for services to the nursing care insurer, which in turn instructs the review board to assess the type and extent of nursing care required. Assessment by the review board is a contractual obligation for the nursing care insurers. It must conform to the needs-criteria guidelines and be conducted in the applicant’s domestic environment. An applicant must consent to the assessment and has to meet certain criteria to qualify for nursing care. For instance, one stipulation is that a need for assistance has existed in significant or high measure for the usual and regularly occurring tasks of everyday life (physical care, nutrition, mobility, housework) due to a physical, mental or emotional illness or disablement for at least 6 months. If the review board determines that the applicant indeed requires nursing, the expert evaluator makes recommendations as to the level of nursing required, as well as the type and extent of measures necessary to reverse, lessen the need for nursing care or prevent the need from becoming greater. The recommendations include whether the care should be provided in the home environment or in a care facility, which specific types of assistance are necessary, whether the tasks should be carried out by an assistant partially or in full, whether the person requiring care needs to be supervised or guided. Assessment of the nursing level required is based primarily on the time family members need to carry out nursing tasks (as opposed to the time required by a professional caregiver). Care classification I is defined as a significant need for care, including at least 90 min a day of support, of which 45 min consists of basic care. Classification II covers those in high need of care, who need assistance at least 180 min (120 min basic care) at least 3 times daily and additionally require help with housework several times a week. Classification III covers those in highest need of nursing, who require at least 300 min of nursing (240 min basic care) every day at any time, including at night, and additionally require help with housework several times a week. If the condition of a nursing recipient worsens, the review board can assign a higher care classification in a follow-up assessment. Fees for the necessary nursing services vary according to the care classification and only in extreme cases can the nursing insurer provide services that exceed the specifications of care classification III, as unlike statutory health insurance, nursing insurance is not subject to the principle of meeting needs.

Government guidelines dictate that, if possible, the nursing should be provided in the recipient’s domestic environment by family members and neighbors. For this reason, one goal pursued by the nursing insurance system is encouraging relatives and neighbors to provide the nursing care. For instance, the nursing insurance law provides for bonus payments for the social security premiums of caregivers. Caregivers also have the right to remuneration for full inpatient care or care by another caregiver or institution for a maximum of 4 weeks per calendar year in cases of illness or to take holidays. In crisis situations, when the home care cannot be ensured by another caregiver or nursing facility, temporary partial or full inpatient care is covered by the nursing insurer, also for up to 4 weeks a calendar year [1, 3] (Table 7).

Table 7.

Number of hospitals and hospital bed [6]

| 2000 | 2007 | |

|---|---|---|

| Inpatient nursing care facility | 8,859 | 11,029 |

| Nursing beds | 645,456 | 799,059 |

Ambulatory nursing in Germany

Ambulatory nursing facilities include welfare centers with a multitude of different, cooperating professions under one roof (nursing staff, social workers, occupational therapists, family therapists) and private nursing care services (usually owned by individuals). A variety of different funding bodies meet the expense of these services. For example, the social nursing insurance company remunerates the nursing services and pays the nursing allowance in cases of long-term care, the statutory health insurance company covers home nursing and domestic assistance, public funding covers social welfare services and investment funding at state level, while private households cover all other costs. The remuneration is paid as lump sums for so-called service packages, which include several frequently required nursing services [1, 3].

Inpatient nursing

Inpatient nursing care can be full-time (24-h care), part-time (only during the day or at night) or short-term (temporary full inpatient nursing for up to 4 weeks per calendar year). As domestic environments, aged homes are not considered to be inpatient nursing facilities. Potential inpatients are entitled to preliminary information in easily understood language, which must explain the services, the available additional services (which have to be remunerated separately on a user-pays basis), fees and the results of quality monitoring. Contracts are generally concluded for an indefinite period and any increase in fees must be clearly justified. A nursing facility resident can only be evicted in important, justifiable cases (in this case, the facility is obliged to find the resident a comparable facility and cover the moving costs). In contrast, a resident can quit the contract at anytime and with immediate effect, if, for instance, significant service deficits exist (here too, the nursing facility must pay for the cost of relocation) [1, 3].

Supply of medicine in Germany

Under German law, medicine is defined as materials and preparations of materials intended to cure, alleviate, prevent or diagnose diseases, ailments, physical injury or other physical complaints when applied to or in the human or animal body. Furthermore, materials used for diagnosis on or in the human body, or which replace bodily fluids (e.g. blood supplies), are also defined as medicine. Generally the medicines are propriety medicinal products; only in rare cases are medicines prepared on-site in pharmacies (e.g. as tinctures). The German Drugs Act (Arzneimittelgesetz, AMG) regulates the manufacture, approval and dispensing of medicine, as well as government monitoring of drug supply. In contrast, the drug price ordinance (Arzneimittelpreisverordnung, AMPreisV) regulates the conditions under which pharmaceutical wholesalers and pharmacists can increase prices. As part of ensuring that medicine supply to humans and animals proceeds according to applicable rules and regulations, the state must provide for safety in the handling and distribution of medicine, in particular for the quality, effectiveness and harmlessness of the medicine. The state meets this obligation by issuing quality standards and monitoring drug manufacturing, distribution and dispensing. The main federal institutions involved in this regulation and monitoring are the Federal Institute for Medicines and Medicine Products (Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte, BfArM), which is responsible for approving proprietary medicinal products, the Paul Ehrlich Institute, which is responsible for approving vaccinations, sera and blood products and the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Healthcare (IQWiG), which assesses the effectiveness, quality and efficiency of pharmaceuticals. State authorization and evidence of special expert knowledge is required to manufacture pharmaceuticals in Germany. Industrial manufacturers include the Federal Association of Pharmaceutical Industry (BPI), the Association of Researching Medicine Manufacturers (VFA) and the Federal Professional Association of Medicine Manufacturers (BAH).

All approved medicines, as well as all companies and institutions that manufacture, assess, store, package or distribute drugs are subject to state monitoring. Manufacturers can be obliged to include particular information a medicine’s package information leaflet, or, in the case of serious side effects, recall the medicine from the market. After detailed assessment, a product is initially approved for 5 years, after which the approval can be extended indefinitely. When a medicine is newly approved, the manufacturer has the right to set the retail price and the drug is protected by patent for a total of 20 years. Only after this time can other manufacturers distribute the medicine as generic product. The manufacturer supplies the approved proprietary medicinal products to pharmaceutical wholesalers, who in turn supply the pharmacies (via a legally regulated distribution channel). Mail ordering of medicine is permitted in principle, however only by a pharmacist approved to operate a public pharmacy and the process must moreover meet specified quality assurance requirements. Excluding hospital pharmacies, the manufacture, distribution and sale is undertaken by private companies (pharmaceutical manufacturers, wholesalers, pharmacies).

The pharmacy law (Apothekengesetz, ApoG) and the rules governing the operation of pharmacies (Apothekenbetriebsordnung, ApBetrO) specify the prerequisites and requirements for the operation of a pharmacy (e.g. apart from government approval by the relevant state authority, a pharmacist’s license is required, and specials requirements regarding the building, equipment and staffing also exist). Pharmacies are divided into public (i.e. open to the public) stores and hospital pharmacies, which only supply inpatients (and under certain conditions, outpatients). Like physicians, pharmacists are obliged to join a state association. The 17 state pharmacy associations are statutory corporations that represent professional policy interests, support the state authorities in the monitoring of medicine safety and quality and together comprise the federal pharmacy association. Furthermore, the profession has organized itself into 17 lobby associations, which together form the German Pharmacists’ Association (Deutscher Apothekerverband), which represents the pharmacists’ economic interests at federal level. The Federal Association of German Pharmacist Associations (ABDA) is the umbrella organization of state-level statutory pharmacists’ associations and lobby associations, and represents the professional interests of pharmacists in the public sphere and in policy questions.

While manufacturers are in principle free to set their prices as they wish, wholesalers and pharmacists must adhere to surcharge limits and guarantee hospitals a legally fixed price reduction of currently 2.30 euros per medicine. Wholesalers and pharmacists must also comply with the mark-up limits for proprietary medicinal products defined in the drug price ordinance (AMPreisV). Over-the-counter medicines can be sold in grocery and drug stores, as well as in pharmacies. In contrast, prescription drugs may only be sold in pharmacies. Yet another class of drugs can only be sold in pharmacies, but do not require a doctor’s prescription. Narcotics are subject to the narcotics law and may only be distributed under special rules and documentation.

SHI insurees are entitled to the provision of medically necessary drugs. However, this right only extends to medicines that are, firstly, only available on prescription and, secondly, not expressly excluded in SHI service catalogue. Only in extremely serious diseases and under strict conditions can non-prescription medicines be prescribed for coverage by the statutory health insurance company. The SHI system is not obliged to cover drugs that relieve minor ailments (e.g. flu and cold medicine, mild painkillers and lifestyle medicines such as appetite suppressants, hair-growth aids, and sexual potency drugs). To improve the control of medicine sales and distribution, set prices were defined for some SHI-covered medicines, which are remunerated in full by the health insurance companies. If higher prices are demanded (e.g. by the pharmacies), the insuree has to pay the difference directly. Additionally, every SHI insuree aged 18 years or more has to pay 10% of the retail price of every prescribed medicine (minimum of 5 euros, maximum of 10 euros). Peculiar to Germany is that physicians are prohibited from dispensing medicine to patients, except for small amounts of samples and medicine required directly during the consultation.

The dispensing of medicine to private patients and SHI insurees is essentially identical, except that private patients are reimbursed for the expense of the medicine rather than receiving the medicine directly. Although the medicine sales and distribution system is also jointly self-governed, the agreements between health insurance companies and SHI-approved physicians, which are subject to the medicine guidelines of the Federal Joint Committee, carry more weight than the framework agreements between the insurance companies and medicine manufacturers or pharmacist associations. As in other aspects of the health system, health insurance companies and the association of SHI physicians have to negotiate the total expenditure on medicine and remedies in advance for the coming year [1, 5, 10, 13] (Tables 8 and 9).

Table 8.

Number of pharmacies [6]

| 2000 | 2009 | |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacies | 21,592 | 21,548 |

Table 9.

Funding of the German healthcare system as compared with international standards (in percent of gross domestic product) [1, 14]

| 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 9.8 | 10.0 | 10.2 |

| Belgium | 8.2 | 8.6 | 10.3 |

| Denmark | 8.1 | 8.3 | 9.1 |

| Finland | 7.5 | 6.6 | 7.5 |

| France | 9.9 | 9.6 | 11.1 |

| Germany | 10.1 | 10.3 | 10.7 |

| Great Britain | 7.0 | 7.3 | 8.3 |

| Greece | 7.5 | 9.3 | 10.1 |

| Ireland | 6.7 | 6.3 | 7.5 |

| Italy | 7.3 | 8.1 | 8.9 |

| Luxembourg | 5.6 | 5.8 | 7.9 |

| Netherlands | 8.3 | 8.0 | 9.2 |

| Portugal | 7.8 | 8.8 | 10.2 |

| Spain | 7.4 | 7.2 | 8.3 |

| Sweden | 8.1 | 8.4 | 9.1 |

| Switzerland | 9.7 | 10.4 | 11.6 |

| USA | 13.3 | 13.2 | 15.3 |

Footnotes

P. Friedemann is National Representative of EPMA in Germany.

Contributor Information

Andrea Döring, Email: andrea.doering@charite.de.

Friedemann Paul, Phone: +49-30-450539040, FAX: +49-30-450539915, Email: friedemann.paul@charite.de.

References

- 1.Simon M. Das Gesundheitssystem in Deutschland. Eine Einführung in Struktur und Funktionsweise. 3rd ed. Hans Huber; 2010.

- 2.Igl G, Welti F. Sozialrecht. Ein Studienbuch. 8th ed. Werner; 2006.

- 3.Gerlinger T, Röber M. Die Pflegeversicherung. 1st ed. Hans Huber; 2009.

- 4.Szabados T. Krankenhäuser als Leistungserbringer in der gesetzlichen Krankenversicherung. 1st ed. Springer; 2009.

- 5.Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Gesetze und Verordnungen aus dem Geschäftsbereich des BMG. 2010. http://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/cln_160/nn_1168278/DE/Service/Suche/Gesetze/gesetze__node.html?__nnn=true. Accessed 2010.

- 6.Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Statistiken zur Gesetzlichen Krankenversicherung, 2010. http://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/cln_151/nn_1168682/DE/Gesundheit/Statistiken/gesetzliche-krankenversicherung__node.html?__nnn=true. Accessed 2010.

- 7.Das Informationssystem der Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. Ausgaben, Kosten, Finanzierung. 2010. http://www.gbe-bund.de/gbe10/abrechnung.prc_abr_test_logon?p_uid=gast&p_aid=54534481&p_sprache=D&p_knoten=TR19200. Accessed 2010.

- 8.Das Informationssystem der Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. Gesundheitsberichterstattung. 2010. http://www.gbe-bund.de/gbe10/abrechnung.prc_abr_test_logon?p_uid=gast&p_aid=54534481&p_sprache=D&p_knoten=TR200. Accessed 2010.

- 9.KBV. Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung. Die ärztliche Selbstverwaltung in der gesetzlichen Krankenversicherung (GKV). 2010. http://www.kbv.de/wir_ueber_uns/83.html. Accessed 2010.

- 10.KBV. Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung. Die Rechtsquellen. 2010. http://www.kbv.de/rechtsquellen/85.html. Accessed 2010.

- 11.PKV. Verband der privaten Krankenversicherung e.V. PKV-Verband. 2010. http://www.pkv.de/verband. Accessed 2010.

- 12.PKV. Verband der privaten Krankenversicherung e.V. PKV und Recht. 2010. http://www.pkv.de/recht. Accessed 201.

- 13.ABDA. Bundesvereinigung Deutscher Apothekerverbände. Fakten und Zahlen. 2010. http://www.abda.de/fakten_zahlen.html. Accessed 201.

- 14.Statistisches Bundesamt Deutschlands. Internationale Daten. 2010. http://www.destatis.de/jetspeed/portal/cms/Sites/destatis/Internet/DE/Navigation/Statistiken/Internationales/Internationales.psml. Accessed 2110.