Abstract

Perinatal asphyxia occurs still with great incidence whenever delivery is prolonged, despite improvements in perinatal care. After asphyxia, infants can suffer from short- to long-term neurological sequelae, their severity depend upon the extent of the insult, the metabolic imbalance during the re-oxygenation period and the developmental state of the affected regions. Significant progresses in understanding of perinatal asphyxia pathophysiology have achieved. However, predictive diagnostics and personalised therapeutic interventions are still under initial development. Now the emphasis is on early non-invasive diagnosis approach, as well as, in identifying new therapeutic targets to improve individual outcomes. In this review we discuss (i) specific biomarkers for early prediction of perinatal asphyxia outcome; (ii) short and long term sequelae; (iii) neurocircuitries involved; (iv) molecular pathways; (v) neuroinflammation systems; (vi) endogenous brain rescue systems, including activation of sentinel proteins and neurogenesis; and (vii) therapeutic targets for preventing or mitigating the effects produced by asphyxia.

Keywords: Neonatal, Hypoxia-ischemia, Predictive diagnostic, Sequelae, Personalised treatments

Introduction

Perinatal asphyxia (PA) or neonatal hypoxia- ischemia (HI) is a temporary interruption of oxygen availability that implies a risky metabolic challenge, even when the insult does not lead to a fatal outcome [1]. Different clinical parameters have been used to both diagnose and predict the prognosis for PA, including non reassuring foetal heart rate patterns, prolonged labour, meconium-stained fluid, low 1-minute Apgar score, and mild to moderate acidemia, defined as arterial blood pH less than 7 or base excess greater than 12 mmol/L [2].

The guidelines of the American Academy of Paediatrics (AAP) and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (ACOG) consider all of the following criteria in diagnosing asphyxia: (i) profound metabolic or mixed acidemia (pH <7.00) in umbilical artery blood sample, if obtained, (ii) persistence of an Apgar score of 0–3 for longer than 5 min, (iii) neonatal neurologic sequelae (e.g., seizures, coma, hypotonia), and (iv) multiple organ involvement (e.g., kidney, lungs, liver, heart, intestines) [3]. Clinically, this type of brain injury is called Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE). The staging system proposed by Sarnat and Sarnat in 1976 is often useful in classifying the degree of encephalopathy. Mild (stage I), moderate (stage II), or severe (stage III) HIE is commonly diagnosed using physical examination, which evaluates the level of consciousness, neuromuscular control, tendon and complex reflexes, pupils, heart rate, bronchial and salivary secretions, gastrointestinal motility, presence or absence of myoclonus or seizures, electroencephalography findings, and autonomic function [4]. However, these parameters have no predictive value for long-term neurologic injury after mild to moderate asphyxia [5].

PA is a major paediatric issue with few successful therapies to prevent neuronal damage. PA still occurs frequently when delivery is prolonged, despite improvements in perinatal care [6–9]. The international incidence has been reported as 2–6/1,000 term births [10, 11], reaching higher rates in developing countries [12–14].

Prognosis and sequelae of perinatal asphyxia

Studies of neurodevelopmental outcome after HIE often give limited information about the children, pooling a wide range of outcome severities. The emphasis in neonatology and paediatrics is on non-invasive diagnosis approaches for predictive diagnostics. Several methods for predicting outcomes in infants with HIE are used in the clinical setting including: neonatal clinical examination and clinical course, monitoring general movements [15, 16], early electrophysiology testing, cranial ultrasound imaging, Doppler blood flow velocity measurements, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and MR microscopy. The neonatal brain MRI provides detailed information about lesion patterns in HIE allowing for earlier and more accurate prediction of long-term outcome [17, 18]. Very recently, a potential serum biomarker for predicting individual predispositions to pathologies or progression of complications induced by asphyxia has been described. As HIE induces changes in blood-barrier permeability [19], a potential correlation between blood and brain can be established. Thus, the presence of specific level of lactate dehydrogenase [20] or free radicals in blood predicts HIE in newborn infant during the first 12 h after birth. This result is of clinical interest offering a potential inexpensive and safe prognostic marker for newborn infants with PA. Long-term follow-up studies are required to correlate the information obtained from early biomarkers predictor with clinical-pathophysiologic outcome.

The time course and the severity of the neurological deficits observed following HI depends upon the extent of the insult, the time lapse before normal breathing is restored and the CNS maturity of the foetus. Severe asphyxia has been linked to cerebral palsy, mental retardation, and epilepsy [7, 21–23], while mild-moderate asphyxia has been associated with cognitive and behavioural alterations, such as hyperactivity, autism [22], attention deficits in children and adolescents [24, 25], low intelligence quotient score [26], schizophrenia [27–29] and development of psychotic disorders in adulthood [30]. In a prospective cohort study of genetic and perinatal influences on the aetiology of schizophrenia [26, 31], it was reported that individuals with hypoxia-related obstetric complications were more than five times more likely to develop schizophrenia than individuals with no hypoxia-related obstetric complications. Moreover, a downregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) has been detected in cord samples of patients exposed to PA who develop schizophrenia as adults [27]. This finding suggests that the decrease in neurotrophic factors induced by HI may lead to dendritic atrophy and disruption of synaptogenesis, effects that are present in individuals destined to develop schizophrenia as adults [27]. Moreover, in a 19-year longitudinal study, it was found that neonatal HI complications were associated with a doubling of the risk for developing a psychotic disorder [32].

Because the majority of studies have focused on detecting major developmental abnormalities at a very young age, we still know little about the less severe difficulties that children may experience later, since different levels of morbidity have been found after mild or moderate PA [33]. To understand the long-term effects of PA on development, it is necessary to follow participants through school age. Specific cognitive functions continue to develop throughout childhood, and subtle functional deficits usually become apparent when a child faces increasing demands to develop complex abilities in school. Different studies have shown that children 2 to 6 years old with mild PA have general intellectual skills comparable to control groups, and those with moderate PA obtain consistently worse results than control groups but without reaching statistically significant, differences [34–36]. When children with moderate PA are tested at 7 to 9 years, they show problems in reading, spelling and math [22, 37, 38]. Given the good prognosis of children with mild PA, the heterogeneity of moderate PA, and the devastating effects of severe PA, some authors have proposed a dose–response effect [9, 37].

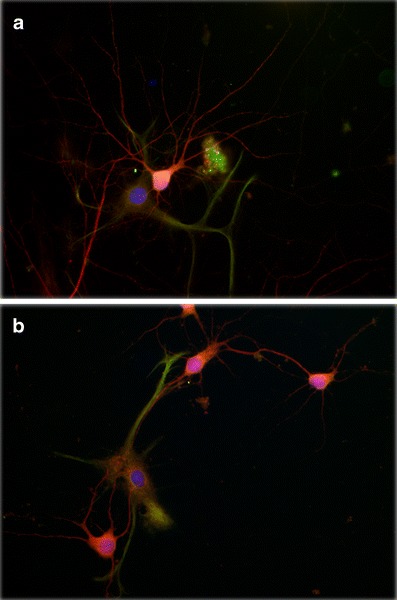

Neurocircuitries of the hippocampus, as well as the basal ganglia [10, 24, 39–43], are particularly vulnerable to HI in the neonate [18, 44–50]. Hippocampus have been associated with specific cognitive functions such as memory and attention and together with striatum, play a role in the pathogenesis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism and schizophrenia [10, 51, 52]. The striatum has also been associated with cerebral palsy, a group of disorders of movement and posture development. Motor abnormalities are often accompanied by disturbances of sensation, perception, cognition, behaviour and/or by a seizure disorder [16]. Term infants exposed to severe HI show focal brain lesions in the peri-Rolandic cortex, ventrolateral thalamus, hippocampus, and posterior putamen on MRI [17, 18, 53, 54], as well as abnormalities in generalized movement patterns at 1 and 3 months of age [16]. This group also shows increased susceptibility for developing cerebral palsy, including athetosis and dystonia, with impaired motor speech and impaired use of the hands compared to the legs [54]. A recent MRI study of a cohort of 175 term infants with PA, with scans obtained at 6 weeks and at 2 years postnatally, provides compatible results [17]. The early MRIs showed marked structural damage to the deep grey matter, hippocampus, or frontal white matter, producing a long-term impact on intellectual function in the children. In particular, memory and attention/executive functions were impaired in children that experienced severe PA. Language problems were also common [17]. These MRI findings provide evidence of the close relationship between the localisation of the lesion, the severity of the HI injury, and the resulting functional impairment. A similar system-selective pattern of network degeneration in the hippocampus has been seen with diffusion tensor MRI in mice with hypoxic-ischaemic injury [55, 56]. In agreement, hippocampal cell death was observed 1 week [57, 58], 1 month [43, 59–61] and 3 months [62, 63] after PA, principally in the CA1, CA3 and dentate gyrus (DG) regions of rats. Moreover, a decrease in synaptogenesis and dendritic branching of pyramidal cells has been found in hippocampal cultures from rats exposed to PA [Rojas-Mancilla et al., in preparation] (see Fig. 1). These effects could be correlated with deficits in neuro-behavioural functions such as hyperactivity, deficits in working memory, non-spatial memory, anxiety, and motor coordination [40, 42, 61, 63, 64–66] and also could be a key factor in the development of neuropathology, including schizophrenia [27].

Fig. 1.

Perinatal asphyxia reduces neurite branching of primary cultured pyramidal neurons from hippocampus. Asphyxia was induced by immersing foetuses-containing uterine horns, removed from ready-to-deliver rats into a water bath at 37°C for 21 min. The cultures were prepared 6 h after delivery. After 14 days in vitro, the cultures were fixed with a formalin solution for assaying neuronal and astroglial phenotype using antibodies against microtubule associated protein-2 (MAP-2, red) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, green) respectively, counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue), a DNA marker. A fluorescent photomicrograph of cultures from a caesarean-delivered control (a), and asphyxia-exposed (b) rats, showing MAP-2 (red) and GPAP (green) positive cells is shown. A significant decrease on neurite branching is observed in asphyctic cultures (b), principally evident in neurites of secondary and tertiary order. Moreover, a relationship between neurons and astrocytes can be observed in both experimental conditions, being more pronounced in astrocytes from asphyctic condition. Scale bar: 20 μm. Taken from Rojas-Mancilla et al., in preparation

Energy deficit and calcium homeostasis

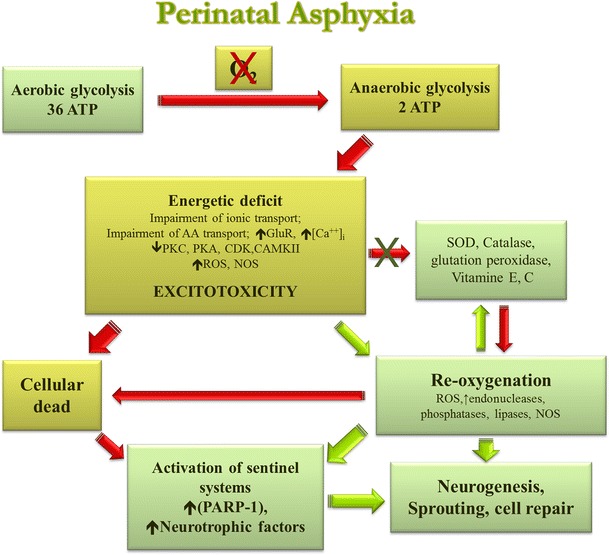

Energy failure occurring in PA leads a radical shift from an aerobic to a less efficient anaerobic metabolism, resulting in a decreased rate of ATP and phosphocreatine formation [67–69], lactate accumulation [70, 71], decreased pH [67, 72], decreased protein phosphorylation [69, 73–75]; and finally, over-production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [76–80] that result in cell death. Deficit in ATP production leads to loss of resting membrane potential [81], disturbances in ionic homeostasis, membrane depolarisation [82], and an increase in extracellular glutamate concentration [70, 83] as shown in Fig. 2. This results in over-activation of the ionotropic NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartic acid), AMPA/KA (Alpha-amino acid-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid/Kainic acid) receptors as well as the G-protein-linked metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR) [82, 84, 85], inducing a massive influx of Ca2+ into cells. The increase in cytosolic Ca2+, in turn, activates proteases, lipases, endonucleases, and nitric oxide synthases that degrade the cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix proteins, producing membrane lipid peroxidation, peroxynitrites, and other free radicals [44, 57, 86, 87]. These events [88–91] elicit a cascade of downstream intracellular processes that finally lead to excitotoxic neuronal damage [92–94] and cell death (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Neuropathological mechanisms induced by perinatal asphyxia in the neonatal brain. Following PA, energy failure leads to a shift from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism, resulting in a decreased rate of ATP and other energy compounds, lactate accumulation, decreased pH, and finally, over-production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). An ATP deficit leads to dissipation of ion gradients and membrane depolarisation, due to pumps decreased protein phosphorylation, with a subsequent increase in extracellular glutamate concentration. This results in over-activation of glutamate receptors inducing a massive influx of Ca2+ into cells, which activates proteases, lipases, endonucleases, and nitric oxide synthases that degrade the cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix proteins, producing membrane lipid peroxidation, peroxynitrites, and other free radicals. These events elicit a cascade of downstream intracellular processes that finally lead to excitotoxic neuronal damage and cell death. At the same time, antioxidative mechanisms get involved and DNA damage triggers the activation of sentinel proteins that maintain genome integrity, such as poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs), but when overactivated, leads to further energy depletion and cell death. Depending upon time after asphyctic injury, re-oxygenation can lead to improper homeostasis, prolonging the energy deficit and/or generating oxidative stress. Oxidative stress has been associated with inactivation of a number of metabolic repair enzymes and further activation of degradatory enzymes, thus extending and maintaining damage. After acute damage, proliferation and sprouting are diminished, in agreement with a decrease in activity of Protein kinase C (PKC) and cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) observed after PA. But at long-term, release of neurotrophic factors promotes neurogenesis and neuritogenesis

In response to the energy deficit, blood flow is redistributed to the heart, brain and adrenal glands in order to ensure oxygen supply to these vital organs. This redistribution occurs at the expense of reduced perfusion of kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, muscles, skeleton and skin [28, 69, 95–97]. In the brain there is also a redistribution of blood flow, favouring the brain stem at the expense of the cortex [98], showing a re-compartmentalisation of structures to privilege survival [69]. Re-oxygenation can lead to improper homeostasis, partial recovery, and sustained over-expression of alternative metabolic pathways, prolonging the energy deficit and/or generating oxidative stress. Oxidative stress is associated with inactivation of a number of enzymes, including mitochondrial respiratory enzymes [69, 99], low capacity of the antioxidant mechanism at this early developmental stage [100–103], high oxidative phosphorylation, high free iron producing hydroxyl radicals, high fatty acid content, high metabolism and low metabolic reserves, high oxygen consumption, and immaturity at birth [8, 102, 104, 105] (see Fig. 2).

Perinatal asphyxia and cell death

The mechanisms of neuronal cell death after PA includes necrosis, apoptosis, autophagia and hybrid cell deaths and/or a continuum of neuronal phenotypes, depending principally on the severity of the insult and the maturational state of the cell [69, 106–109]. An initial decrease in high-energy phosphates results in impairment of the ATP-dependent Na+-K+ pump, which after the severe insult causes an acute influx of Na+, Cl−, and water with consequent cell swelling, cell lysis, and thus early cell death by necrosis. Conversely, a less severe insult causes membrane depolarisation followed by a cascade of excitotoxicity and oxidative stress, leading to delayed cell death, principally apoptosis. Thus, necrosis can be observed within minutes, while apoptosis takes more time to develop [110]. Apoptosis is triggered by the activation of endogenous proteases caspases, resulting in cytoskeletal disruption, cell shrinkage, and membrane blebbing. The nucleus undergoes chromatin condensation and nuclear DNA degradation resulting from endonuclease activation [111]. Since apoptosis requires energy, a determinant factor of when cells die is likely the ability of mitochondria to provide adequate energy. Another determinant of classic apoptosis is the loss of neuronal connections, which can continue days to weeks after injury, because groups of cells seem to commit to die [106]. Apoptosis is the more prevalent type of delayed cell death in the perinatal brain, and both caspase-dependent and caspase-independent mechanisms of apoptotic cell death have been recognised [43, 69, 83, 112, 113]. Thus, multiple cell death mediators are activated by neonatal HI injury, including various members of the Bcl-2, Bcl-2-associated X protein (BAX), Bcl-2-associated death promoter (BAD) [43, 114, 115] death receptor [116], and caspases [117, 118] protein families, correlating with increased apoptosis in the brain [119, 120]. After neonatal insult, markers of apoptosis (cleaved caspase-3) and necrosis (calpain-dependent fodrin breakdown product) can be expressed by the same damaged neurons [121], suggesting that the “continuum” could be explained by a failure of some dying cells to complete apoptosis, due to a lack of energy and mitochondrial dysfunction [106, 113, 122]. HI also increases markers for autophagosoma (microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3–11) and lysosomal activities (cathepsin D, acid phosphatase, and β-N-cetylhexosaminidase) in cortical and hippocampal CA3-damaged neurons, suggesting an activation of autophagic flux that may be related to the apoptosis observed in delayed neuronal death after severe HI [84, 108].

Increased knowledge of the factors that determine when or how cells die after HI is important since it might be possible to salvage tissue using drugs, growth factors, or interventions that influence brain activity and restore the damaged neurocircuitry.

Perinatal asphyxia and neurotransmission systems

Glutamatergic system

The depletion of energy reserves that accompanies prolonged hypoxia results in neuronal depolarisation and the release of excitatory amino acids into the extracellular space [69, 123–126], in concentration that exceed both the glial reuptake capacity that is further compromised by energy failure [127] and re-uptake into the synaptic nerve terminal [128]. Thus, glutamate and aspartate accumulate to excitotoxic levels [86, 92–94]. Glutamate activates ionotropic NMDA, AMPA/KA and metabotropic receptors. AMPA/KA receptor activation increases sodium conductance, depolarising the membrane and activating voltage-dependent calcium channels including the NMDA receptor channel. Metabotropic receptors mGluR1-mGluR5, through second messengers, mobilise calcium from intracellular reservoirs to the cytosolic compartment, activating proteases, lipases and endonucleases, which in turn initiate a process of cell death [44, 86, 129, 130]. In fact, a transient increase in excitatory amino acid levels has been found in several experimental models of HI and in the cerebrospinal fluid of human newborn [85, 125, 131, 132]. The importance of NMDA-mediated injury in the immature brain is related to the fact that NMDA receptors are functionally up regulated in the perinatal period because of their role in activity-dependent neuronal plasticity [94]. Immature NMDA channels has a higher probability of aperture and conductance than adult channels, and the voltage-dependent magnesium block that is normally present in adult channels at resting membrane potentials, is more easily relieved in the perinatal period [84, 133]. Thus, increased expression and phosphorylation of NR1 subunits of NMDA receptors have been observed in the striatum after PA. This change is correlated with increased excitability and neurodegeneration during the neonatal period [134, 135]. Moreover, a deficiency in the GluR2 subunit of AMPARs during development has been correlated with increased susceptibility to HI at the regional and cellular levels [136, 137]. Recent studies further suggest crosstalk between inflammation and excitotoxic neuronal damage. It has been shown that the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α is one of the most potent regulators of AMPAR trafficking to and from the plasma membrane, and that it can rapidly increase the proportion of Ca2+-permeable AMPAR at the surface. In combination with increased extracellular glutamate levels, this enhances excitotoxic cell death [85, 138].

The pharmacological blockade of glutamate receptors markedly protects against brain injury induced by severe hypoxia [139–142], reinforcing the idea that glutamatergic receptors during the perinatal period are most susceptible over-activation, promoting the excitotoxicity found after hypoxic ischaemic insults.

Astrocytes also play an important role in preventing neurotoxicity by glutamate uptake [143–147] and are affected by the energy deficit induced by PA as described earlier. Indeed, a decrease in glutamate uptake has been observed in the hippocampus of rat pups subjected to 15 min of PA [148] and a similar result has been observed in the cortex, basal ganglia and thalamus of piglets [149]. Reduced glutamate uptake is correlated with a down-regulation of astrocytic excitatory amino acid transporters EAAT-1 and EAAT-2 [150] after HI, reinforcing the idea that energy deficits also promote a severe disruption of astrocytic cell function.

Dopaminergic and nitridergic system

Mesencephalic dopamine (DA) neurons are essential for the control of motor and cognitive behaviour, and are associated with multiple psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders [151]. In recent years, increasing evidence shows that the monoamine neurotransmitters, particularly DA, may aggravate damage to the brain induced by HI. The striatum, a region richly innervated by the nigrostriatal dopaminergic pathway, is especially susceptible to asphyctic neuronal damage [47].

Levels of DA as well as its metabolites may remain elevated even after normoxia is stabilised [152], due to an impaired DA uptake mechanism [153, 154]. It has been suggested that during HI, the increase in extracellular DA levels can result in alterations in the sensitivity of neurons to the excitatory amino acids [155, 156]. Furthermore, glutamate and aspartate levels are increased, mainly in mesencephalic tissues [70]. A proposed mechanism for the neurotoxic effect of DA is through an increase in the production of free radicals during the re-oxygenation period [157, 158]. This is in agreement with evidence showing that neuronal injury occurring during re-oxygenation after an asphyctic insult is partly due to oxygen free radical-mediated oxidative events [159–161]. PA also induces change in the expression and pharmacological parameters of dopaminergic receptors in the meso-telencephalic DA systems [125]. In addition, asphyxia induced an increase of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) mRNA in the projection fields, striatum and limbic regions, at 1 week. PA did not appear to exert any effect on D1R mRNA levels. These changes may affect D2R and D1R expression differently during development, contributing to long-term imbalances in neurocircuitry [162].

The postnatal establishment of DA neuronal connectivity can be disturbed by metabolic insults occurring at birth. Indeed, it has been shown that PA, alters the establishment of DA neurocircuitries, with long-term consequences. [163]. In our studies, we have shown decreased TH labelling, together with decreased cell viability in substantia nigra (SN) of hypoxic rat brains, suggesting an increased vulnerability of DA cells to hypoxic insult [90, 163]. It was reported that foetal asphyxia induced at E17 by 75-minute clamping of the uterine circulation causes long-term deficits in DA-mediated locomotion in rats, which was related to loss of dopaminergic neurons in the SN, probably associated with nigrostriatal astrogliosis [164]. The molecular changes in glial cell survival following PA are not fully established yet, and the resulting effects of astrocytic alterations on neuron survival and neurite outgrowth and branching should be determined.

In vivo, neuritogenesis depends on signals from neighbouring and distant cells to guide the growth cone to the targets [151, 163, 165]. The expression of guidance proteins such as semaphorins, ephrins, netrins, Slits and their cognate receptors and corresponding growth cones are likely the primary targets for the effect of metabolic insults on the CNS [151]. DA fibres start to invade the neostriatum before birth [166], but DA-containing axon terminals establish a mature targeting several weeks after birth [167]. In the neostriatum, TH immune-reactive fibres have been shown decrease after PA [62], and the dendrite branching of dopaminergic neurons evaluated in organotypic cultures show decreased secondary and higher order dendrite branching after asphyxia [90, 163]. These observations could indicate a modification in attractive and repulsive signals, perhaps suggesting a role for semaphorins, which have been shown to be particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress [168].

Furthermore, the neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) positive neurons in neostriatum show alterations after PA, evidenced by a decrease in number and complexity of neurite trees. It is interesting that in the SN the number of nNOS-positive neurons increases [89, 90], revealing that the interactions amongst DA and nNOS neurons in mesencephalon and telencephalon are regionally different [169, 170].

Finally, there are several studies indicating increased anxiety following PA [61]. Anxiety has been associated with the neurocircuitries involving neurons of the ventral hippocampus, the prefrontal cortex and amygdale that are regulated by dopaminergic innervation [171, 172]. Since the DA pathways have shown to be particularly vulnerable to PA [62, 70, 90, 162, 173], it is tempting to hypothesise that the anxiety-like behaviour is linked to an impairment of DA transmission.

Perinatal asphyxia and neuroinflammation

Recently, the interconnection between the immune and neuronal systems has been a focus of several studies, especially in the context of pathogenesis, in which sustained or excessive inflammation has been associated with neurotoxicity and numerous neuropathologies [174–177].

One major hallmark of neuroimmflamation is the activation of microglia, which are resident parenchymal cells of the brain, derived from the same myeloid lineage as macrophages and dendritic cells [178]. If brain injury occurs, microglia activate, changing the pattern of secreted molecules and activating de novo synthesis of inflammation-related molecules [179]. Microglial activation has beneficial effects for the removal of cell debris, which attenuates inflammatory responses and promotes the remodelling of the affected area. However, over-activation of microglia can exacerbate neuronal death, because inflammatory molecules contribute to a detrimental environment, causing secondary damage [180]. Hence, the balance between a properly modulated or exacerbated immune response is fundamental for biological homeostasis.

Following HI, local inflammation is produced by activated microglia [181], probably due to necrotic cell death, producing a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMPs). Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are expressed by microglial cells [175], sensing the DAMPs [182] and inducing the activation of the major transcription factor associated with inflammatory response, i.e. NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells). Following asphyctic injury, NF-κB is rapidly activated in neurons and glial cells [183, 184]. Indeed, it has been shown that NF-κB p65 is up-regulated in the rat brain 10 min post-PA [185]. An increase in the transcriptional function of NF-κB due to microglia activation leads to the induction of several genes associated with the innate immune response, including proinflammatory cytokines such as: Tumoral necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), Interleukin-10 (IL-10), Interferon gamma (INF-γ), and proteases such as matrix metalloproteinases 3 and 9 (MMP-3 and MMP-9) [186–189].

In humans, a relationship has been established between pro-inflammatory cytokine serum level and outcome for infants with PA. Infants who die or develop cerebral palsy had high plasma levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines as compared to infants with normal outcomes [190]. In agreement, blood levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α are correlated with cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) levels of IL-1β in infants with HIE during the first 24 h of life [191]. Thus, cell damage during PA is associated with microglia-mediated inflammation [192] and inflammatory markers may be useful in predictive diagnostics for PA-induced brain damage and clinical outcomes.

Perinatal asphyxia and sentinel proteins

PA negatively affects the integrity of the genome, triggering the activation of sentinel proteins that maintain genome integrity, such as poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs) [193], X-Ray Cross Complementing Factor 1 (XRCC1), DNA ligase IIIα [194], DNA polymerase β [195, 196], Excision Repair Cross-Complementing Rodent Repair Group 2 (ERCC2) [185, 197, 198] and DNA-dependent protein kinases [199].

PARP-1 is a member of the nuclear chromatin-associated PARPs proteins. PARP-1 catalyses the formation of poly (ADP-ribose) polymers (pADPr) from nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), releasing nicotinamide as a product [200, 201]. pADPr is then transferred to glutamic acid or aspartic residues of acceptor proteins, modifying them post-translationally [201, 202].

When PARP-1 is activated, intracellular levels of pADPr increase about 10 to 500 times [201]. It has been proposed that DNA damage induces the binding of PARP-1 to DNA, promoting the recruitment of the DNA repair machinery [195, 203]. Activated PARP-1 acts as a transcription regulator, unravelling the superstructure of chromatin and regulating the transcriptional activity of various genes, including nitric oxide synthase, chemokines and integrins. Thus, PARP-1 is involved in the regulation of various processes, including DNA replication, repairment, transcription, mitosis, proteins degradation and inflammation [201].

Despite the beneficial effects of PARP-1 activation for important cellular functions, enhanced pADPr formation can be detrimental, leading to various forms of cell death [204]. Normally, in mild DNA damage, PARP facilitates DNA repair by interacting with DNA repair enzymes such as DNA polymerase, XRCC1 and DNA-dependent protein kinase, allowing cells to survive. When the DNA damage is irreparable, caspase-dependent cell death, mediated by caspase 3 and caspase 7, degrades PARP-1 into two fragments of 89 and 24 kDa [205]. Therefore, the cell is eliminated by apoptosis. It has also been reported that the accumulation of pADPr promotes the release of AIF (Apoptosis-inducing factor) from the mitochondria, leading to cell death through caspase-independent apoptosis [201]. However, when DNA damage is severe, PARP-1 is over activated, depleting intracellular NAD+ levels, and consequently ATP [68]. This energy-compromised state inhibits many cellular processes, including apoptosis, and promotes necrosis [206]. Severe DNA damage is usually triggered by a massive degree of oxidative stress triggered by reactive oxygen species such as peroxynitrite, hydroxyl and superoxide free radicals. Thus, the effect of PARP-1 activity depends greatly on the intensity of DNA damage.

Asphyctic injury is characterised by low energy availability, because of a lack of oxygen. In this context, PARP-1 over activation is especially critical for cell survival. Many asphyctic models suggest the importance of energy depletion in this clinical condition [207–209] and note that PARP-1 inhibitors can avoid excessive energy decreases [91, 210, 211]. Consistently, restoring NAD+ can prevent changes induced by PARP-1 over-activation [193].

Perinatal asphyxia and neurogenesis: endogenous brain rescue

Several compensatory mechanisms, including neurogenesis, have been proposed as mediators of endogenously triggered protection against delayed cell death [120, 212–216]. Indeed, increased neurogenesis has been observed in brain regions affected by HI [120, 214, 217, 218], including DG, CA1 [43, 213, 219, 220], subventricular zone (SVZ) [221, 222], neostriatum [223] and neocortex [224, 225]. It has been suggested that new cells produced in SVZ can migrate to the lesioned regions [226–229], attracted by stromal cell-derived migratory signalling. When the new cells arrive in the lesioned region, they form functional connections [223]. Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) has been identified as a factor promoting cell survival and neurogenesis [229–231], through activation of the MAPK (Mitogen-activated protein kinases)/extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) pathway [43, 232]. Also, the expression of bFGF has been observed to be upregulated in DG and SVZ following PA [43, 222, 233, Espina-Marchant et al., in preparation]. Recently, we have reported evidence suggesting that bFGF, through activation of the MAPK/ERK pathway is one of the mechanisms involved in neurogenesis induced by PA [43, 61, Espina-Marchant et al., in preparation]. Several proteins have been identified as modulators of the transduction cascade elicited by bFGF receptors (FGFR) during embryogenesis, including Spry (Sprouty), Sef (similar expression to FGF) and FLRT3 (leucine-rich repeat trans-membrane protein) [234]. Spry and Sef provide inhibitory regulation, while FRLT3 stimulates the activation of FGFR and ERK [235]. Whether these pathways regulate the cellular response to injury postnatally is not yet known, but recent studies have shown that FLRT3, Sef, and Spry proteins are up regulated following PA, with specific temporal and regional patterns [Morales et al., in preparation]. Indeed, neurogenesis can be regulated by a large number of molecules, including growth and neurotrophic factors [236, 237], neurotransmitters, such as dopamine [238] and serotonin [239–241] and other factors still under characterisation.

Striatal dopamine de-afferentation has been reported to increase neurogenesis in the adult olfactory bulb [242], although the mechanism by which this occurs is still unknown. Furthermore, it has been shown that D2 and D3 dopamine receptor stimulation promotes proliferation of neural progenitor cells in both SVZ [243], and hippocampus [244] while D1 receptor stimulation has also been shown to modulate neurogenesis, but indirectly, via GABAergic neurons [245]. Dopaminergic fibres targeting the SVZ and hippocampus originate in mesencephalon (SNC and VTA). These fibres establish anatomical and functional contacts with cell precursors that express DA receptors [238]. When treated with apomorphine, a non-selective DA receptor agonist [246] or a combination of D1 and D2 agonists [247], the synthesis and release of growth factors associated with neurogenesis, such as bFGF [246, 248], BDNF, epidermal growth factor (EGF), Nerve growth factor (NGF), ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF). CNTF and glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) is increased [237, 249–252], promoting cell proliferation [247]. To date, the role of different dopamine receptors in asphyxia-induced neurogenesis has not been characterised. The issue is however relevant, because indirect dopamine agonists are used for treating attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a disorder strongly associated with PA [253]. Furthermore, it is clear that the issue of specific DA receptors must be investigated, because receptor multiplicity exists, conveying different and, sometimes opposing responses [254]. Recently, using organotypic cultures from DG, we investigated whether DA receptors are involved in the modulation of neurogenesis induced by PA. When treated with apomorphine (Apo), there was an increase in the number of BrdU+ cells (a mitosis marker) and BrdU+/MAP2+ (neuronal marker) cells in DG organotypic cultures from asphyxia-exposed, but not from control rats. Since PA induces a decrease in DA levels and an increase in DA receptor mRNA expression in DA target regions, it is possible that the effect of Apo on neurogenesis is via DA receptors rendered supersensitive by the asphyctic insult. Supersensitive receptors could also be located on astrocytes, releasing growth and neurotrophic factors, or directly on neural stem cells, driving a neuronal phenotype. Therefore, further progress is needed in understanding the subjacent mechanisms involved in the modulation of neurogenesis after brain insults, in order to develop novel therapeutic strategies for restoring the damaged neurocircuitry.

Emerging targets for early intervention and neuroprotection

Although understanding of the pathophysiology of PA is gradually increasing, individual therapeutic options for preventing or mitigating the effects produced by the insult are limited. In the last years, therapies have focused in reducing the effects caused by secondary neuronal damage and restoring the functionality of neurocircuitry. Recent progress with several promising neuroprotective compounds has been focussed on the first phase of HI insult including channel blockage (anti-convulsant or anti-excitatory), anti-oxidation, anti-inflammation [255] and apoptosis inhibitors. In later phase PA injury therapies that target the promotion of neuronal regeneration by stimulation of neurotrophic properties of the neonatal brain using growth factors and stem cell transplantation show promise [256–258].

Hypothermia has also proven to be an effective treatment to reduce neuronal injury secondary to hypoxia in animal models [259–261] and is currently applied in the clinic [257, 262–264]. The protective effects of hypothermia have been associated with inhibition of proteases and calpain activation, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and mitochondrial failure, free radical damage, lipid peroxidation and inflammation [257, 265]. In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of the 13 clinical trials published to date, therapeutic hypothermia was associated with a highly reproducible reduction in the risk of the combined outcome of mortality or moderate-to-severe neurodevelopmental disability, severe cerebral palsy, cognitive delay, and psychomotor delay but had higher incidences of arrhythmia and thrombocytopenia in childhood. In agreement, randomised controlled trials have shown that mild therapeutic hypothermia (≤34°C head cooling) [266] with or without whole-body cooling [267], reduces death and disability in these infants when initiated within 6 h of birth [84, 268]. However, there is concern for a narrow therapeutic window [261] and the lack of a clear mechanism of action for the effect of hypothermia [63, 69, 259, 269]. Combining pharmacological interventions with moderate hypothermia is probably the next step to fight HI brain damage in the clinical setting. Indeed, improved neuroprotection in the asphyxiated newborn has reportedly when hypothermia has been combined with anticonvulsant or antiexcitatory drugs including phenobarbital [270, 271], topiramate [272, 273], levetiracetam [274], memantine [273], xenon [275], magnesium sulphate [276], and bumetanide [277]. Further studies should concentrate on more rational pharmacological strategies by determining the optimal time and dose to inhibit the various potentially destructive molecular pathways and/or to enhance endogenous repair while avoiding adverse effects. The dissemination of this new therapy will require improved identification of infants with HIE and regional commitment to allow these infants to be cared for in a timely manner. Continued assessment of long-term outcomes of patients enrolled in completed trials should be a key priority to confirm the long-term safety of hypothermia and other therapeutics interventions.

PARP-1 inhibition as a neuroprotection target is a relatively novel therapeutic strategy for HI but requires systematic characterisation of substances with inhibitory potential. It also requires evaluating the inhibitory potential of drugs already used in paediatrics, but for different indications. Ultrapotent novel PARP inhibitors are now being used in human clinical trials for reducing cell necrosis following stroke and/or myocardial infarction, and for down regulating multiple pathways of inflammation and tissue injury following circulatory shock, colitis or diabetic complications [278]. However, applying ultrapotent PARP inhibitors during development could be dangerous since it has been shown that PARP-1 is required for repair of damaged DNA and other important functions [279, 280]. Therefore, it has been suggested that moderate PARP-1 inhibitors should be chosen for neuronal protection during development [219, 281]. Several natural compounds have been investigated for possible protection against insults leading to over-activation of PARP-1. Nicotinamide, an amide of nicotinic acid (vitamin B3/niacin) has a broad spectrum of neuroprotective functions in a variety of health conditions [282–285]. Nicotinamide protects against oxidative stress [286, 287], ischaemic injury [288] and inflammation [289] by replacing the depletion of the NADH/NAD+ pair produced by PARP-1 after activation to repair hypoxic injury-induced DNA damage [283, 290]. We have reported that therapeutic doses of nicotinamide (0.8 mmol/kg, i.p.) produced a long-lasting inhibition of PARP-1 activity measured in brain and heart from asphyxia-exposed and control rats [Allende-Castro et al., in preparation]. Nicotinamide prevents several of the long term changes induced by PA on monoamines, including changes in the number of nNOS+ cells, neurite length, and number of TH-positive neurites, even if the treatment is delayed for 24 h, suggesting a clinically relevant therapeutic window [89, 90, 291, 292]. Moreover, nicotinamide also prevents the effects elicited by PA on apoptosis, working memory, anxiety and motor alterations [42, 61]. Thus, nicotinamide prevents, with a wide therapeutic window, long-term neuronal deficits induced by PA. Further, its pharmacodynamic properties provide advantages over more selective compounds, in particular its low potency in inhibiting PARP-1. This quality is useful if the compound is administered during the neonatal period, because the drug will only antagonise the effect of PARP-1 overactivation, without impairing normal DNA repair and cell proliferation. Furthermore, nicotinamide can constitute a lead for exploring compounds with a similar pharmacological profile. Some caffeine metabolites, but not caffeine itself, are inhibitors of PARP-1 at physiological concentrations, including theophylline (1,3-dimethylxanthine) [219] and paraxanthine (1,7-dimethylxanthine) [281, 293]. We are particularly interested in testing the substituted benzamide (N-(1-ethyl-2-pyrrolidinylmethyl)-2-methoxy-5-sulphamoyl benzamide) and other benzamides currently in clinical use in paediatrics; and the xanthine analogues, 1,3-dimethylxanthine and 1,7-dimethylxanthine, that are, already used for different clinical applications.

As described, inflammation plays an important role in the excitooxidative cascade of injury in the perinatal period [107]. Antiinflammatory agents have been shown to be effective in the treatment of brain injury by blocking microglial activation and thereby, reducing brain levels of IL-1β [186]. Treatment with an NFkB inhibitor also provides substantial protection against neonatal HI by inhibiting apoptosis [255]. Similar results have been found using other antiinflammatory or antioxidant drugs, such as, minocycline [186], N acetyl cysteine (a glutathione precursor) [294], indomethacin [256], melatonin (a natural potent free radical scavenger activating antioxidant enzymes) [295], allopurinol (a xantine-oxidase inhibitor) [296], pomegranate polyphenols (antioxidant) [297], 2-iminobiotin (inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase) [255], and necrostatin 1 (specific inhibitor of necroptosis) [84, 258, 298].

Recent advances in regenerative medicine suggest that neurotrophic factors and/or stem cell transplantation may improve repair of the HI-damaged brain. Neurotrophic factors including insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) [266, 299], NGF [300], BDNF [301] and bFGF [302] reduce long-term HI-induced brain damage and improve recovery of behaviour in immature rats. Several authors have also reported beneficial effects of stem cell transplantation [303–309]. Several types of stem cells including neuronal stem cells (NSC), mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) [308, 310, 311] and haematopoietic stem cells (HSC) [305] have been transplanted in both neonatal and adult animal models of ischaemic brain damage, promoting functional as well as anatomical recovery [305, 307–309, 312, 313]. Regenerative effects of stem cell transplantation likely involve both replacement of damaged cells by exogenous cells as well as improvement of endogenous repair processes by releasing trophic factors [303, 308, 310, 311]. Indeed, a single hemispheric injection with MSC 10 days after HI induced an up regulation of genes involved in cell survival, proliferation and neurogenesis. Two injections of MSC induced expression of genes involved in cell proliferation, as well as, differentiation and network integration [308]. Intraperitoneal transplantation of human umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells (HUCB), 3 h after the HI insult, resulted in better performance of two developmental sensorimotor reflexes, in the first week after the injury [306]. Moreover, a neuroprotective effect in the striatum, and a decrease in the number of activated microglial cells in the cerebral cortex of treated animals were observed suggesting that HUCB transplantation might rescue striatal neurons from cell death after a neonatal HI injury resulting in better functional recovery [314]. Recently, the potential use of stem/progenitor cell therapies for neuroprotection or regeneration after neonatal HI has been evaluated in several preclinical studies, and the most promising results are now being tested in clinical trials [315].

Conclusions & outlook

The present review addresses a clinically relevant problem with both paediatric and neuropsychiatric implications. PA is a main cause of newborn death and long-term neurological damage still without a predictive diagnostics, preventive and/or treatment of consensus.

An early diagnosis for predictive diagnostics of PA is of vital importance in planning the short- and long-term care of the infant. The emphasis in neonatology and paediatrics is on non-invasive diagnosis approaches for predictive diagnostics.

Advances in the diagnosis and early predictive biomarkers of PA outcome have been achieved, but still need improvement. Long-term follow-up studies are required to correlate the information obtained with the early predictive biomarkers and clinical-pathophysiological outcome.

Significant progress in understanding the pathophysiology of asphyxia is being achieving, providing a valuable framework on understanding the predisposition to develop metabolic, neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases at adult stages. It is expected that future studies will allow the identification of critical molecular, morphological, physiological and pharmacological parameters, specifying variables that should be considered when planning neonatal care and development programmes.

Emerging targets for early intervention and neuroprotection have been focussed on the inhibition of various potentially destructive molecular pathways including excitotoxicity, inflammation, oxidative stress and cell death, and/or therapies that target on restoring functionality of neurocircuitries by stimulation of neurotrophic endogenous properties of the neonatal brain using growth factors and stem cell transplantation. The use of these novel interventions alone or in combination is very attractive and needs further research.

In summary, the individual prediction, targeted prevention and personalised treatments of newborn with asphyctic deficits, is priority in neonatology and paediatrics care. Advanced strategies in development of robust diagnostic, biomarker and potential drug-targets approaches are the main goal for future research.

Acknowledgements

We would like to grateful to Professor Andrew Tasker for critical and helpful comments on the manuscript. We thank Professor Mario Herrera-Marschitz for the valuable support and guideline. This work was supported by FONDECYT-Chile (1110263, 1080447 and 11070192), CONICYT/DAAD (1378-09529), Institute Millennium-BNI research grants, CONICYT PhD Fellows (PEM, MGH and ERM) and MECESUP (UCh0714) PhD Fellow (TNP).

Glossary

- AA

Amino acids

- AAP

American academy of paediatrics

- ACOG

American college of obstetrics and gynaecology

- ADP-ribose

Adenine diphosphate-ribose

- ADHD

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- AIF

Apoptosis-inducing factor

- AMPA

Alpha-amino acid-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid

- Apo

Apomorphine

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- BAD

Bcl-2-associated death promoter

- BAX

Bcl-2-associated X protein

- BCL-2

B-cell lymphoma 2

- BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- bFGF

Basic fibroblast growth factor

- BrdU

5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine

- CA

Cornus ammonis

- CAMKII

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase

- Cdk

Cyclin-dependent kinases

- CNS

Central nervous system

- CNTF

Ciliary neurotrophic factor

- CSF

Cerebral spinal fluid

- DA

Dopamine

- DAMPs

Damage-associated molecular patterns

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DG

Dentate gyrus

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- EAAT

Excitatory amino acid transporter

- EGF

Epidermal growth factor

- ERCC2

Excision repair cross-complementing rodent repair group 2

- ERK

Extracellular signal-regulated kinases

- FGFR

Fibroblast growth factor receptor

- FLRT3

Leucine-rich repeat transmembrane protein

- GDNF

Glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GluR

Glutamate receptor

- HI

Hypoxia-ischaemia

- HIE

Hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy

- HSC

Haematopoietic stem cells

- HUCB

Human umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells

- IGF-1

Insulin-like growth factor-1

- IL

Interleukin

- INF-γ

Interferon gamma

- iNOS

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IQ

Intelligence quotient

- KA

Kainic acid

- MAP-2

Microtubule associated protein-2

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinases

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- mRNA

Messenger ribonucleic acid

- MSC

Mesenchymal stem cells

- NAD

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide oxided form

- NADH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide reduced form

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- NGF

Nerve growth factor

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartic acid

- nNOS

Neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- NSC

Neuronal stem cells

- PA

Perinatal asphyxia

- pADPr

Poly ADP-ribose polymers

- PARP-1

Poly ADP-ribose polymerase subtype 1

- PKA

Protein kinase A

- PKC

Protein kinase C

- ROS

Reactive oxidative species

- SNAP-25

Synaptosomal-associated protein 25

- SNc

Substantia nigra pars compacta

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- SVZ

Subventricular zone

- TCA

Tricarboxylic acid cycle

- TH

Tyrosine hydroxylase

- TLRs

Toll-like receptors

- TNF-α

Tumour necrosis factor-alpha

- VTA

Ventral tegmental area

- XRCC1

X-ray cross complementing factor 1

Contributor Information

Paola Morales, FAX: +56-2-7372783, Email: pmorales@med.uchile.cl.

Diego Bustamante, Email: dbustama@med.uchile.cl.

Pablo Espina-Marchant, FAX: +56-2-7372783, Email: pa_espina@med.uchile.cl.

Tanya Neira-Peña, FAX: +56-2-7372783, Email: tanyaneira@gmail.com.

Manuel A. Gutiérrez-Hernández, FAX: +56-2-7372783, Email: manugut@med.uchile.cl

Camilo Allende-Castro, FAX: +56-2-7372783, Email: allende.camilo@gmail.com.

Edgardo Rojas-Mancilla, FAX: +56-2-7372783, Email: esrojas@med.uchile.cl.

References

- 1.Herrera-Marschitz M, Morales P, Leyton L, Bustamante D, Klawitter V, Espina-Marchant P, et al. Perinatal asphyxia: current status and approaches towards neuroprotective strategies, with focus on sentinel proteins. Neurotox Res. 2011;19:603–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.MacLennan A. A template for defining a causal relation between acute intrapartum events and cerebral palsy: international consensus statement. BMJ. 1999;319:1054–1059. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7216.1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology., Task Force on Neonatal Encephalopathy and Cerebral Palsy., American Academy of Pediatrics. Neonatal Encephalopathy and Cerebral Palsy: Defining the Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology. Edited by Washington, DC, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2003.

- 4.Sarnat HB, Sarnat MS. Neonatal encephalopathy following fetal distress. A clinical and electroencephalographic study. Arch Neurol. 1976;33:696–705. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1976.00500100030012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leuthner SR, Das UG. Low Apgar scores and the definition of birth asphyxia. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51:737–745. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger R, Garnier Y. Perinatal brain injury. J Perinat Med. 2000;28:261–285. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2000.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volpe JJ. Perinatal brain injury: from pathogenesis to neuroprotection. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2001;7:56–64. doi: 10.1002/1098-2779(200102)7:1<56::AID-MRDD1008>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vannucci SJ, Hagberg H. Hypoxia-ischemia in the immature brain. J Exp Biol. 2004;207:3149–3154. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Low JA, Robertson DM, Simpson LL. Temporal relationships of neuropathologic conditions caused by perinatal asphyxia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:608–614. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(89)80040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haan M, Wyatt JS, Roth S, Vargha-Khadem F, Gadian D, Mishkin M. Brain and cognitive-behavioural development after asphyxia at term birth. Dev Sci. 2006;9:350–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2006.00499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurinczuk JJ, White-Koning M, Badawi N. Epidemiology of neonatal encephalopathy and hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawn J, Shibuya K, Stein C. No cry at birth: global estimates of intrapartum stillbirths and intrapartum-related neonatal deaths. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:409–417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawn JE, Kerber K, Enweronu-Laryea C, Cousens S. 3.6 million neonatal deaths—what is progressing and what is not? Semin Perinatol. 2010;34:371–386. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wall SN, Lee AC, Carlo W, Goldenberg R, Niermeyer S, Darmstadt GL, et al. Reducing intrapartum-related neonatal deaths in low- and middle-income countries-what works? Semin Perinatol. 2010;34:395–407. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prechtl HF, Einspieler C, Cioni G, Bos AF, Ferrari F, Sontheimer D. An early marker for neurological deficits after perinatal brain lesions. Lancet. 1997;349:1361–1363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)10182-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrari F, Todeschini A, Guidotti I, Martinez-Biarge M, Roversi MF, Berardi A, et al. General movements in full-term infants with perinatal asphyxia are related to basal ganglia and thalamic lesions. J Pediatr. 2011;158:904–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Martinez-Biarge M, Diez-Sebastian J, Rutherford MA, Cowan FM. Outcomes after central grey matter injury in term perinatal hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:675–682. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cowan F, Rutherford M, Groenendaal F, Eken P, Mercuri E, Bydder GM, et al. Origin and timing of brain lesions in term infants with neonatal encephalopathy. Lancet. 2003;361:736–742. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12658-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar A, Mittal R, Khanna HD, Basu S. Free radical injury and blood–brain barrier permeability in hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e722–e727. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karlsson M, Wiberg-Itzel E, Chakkarapani E, Blennow M, Winbladh B, Thoresen M. Lactate dehydrogenase predicts hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy in newborn infants: a preliminary study. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:1139–1144. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramin SM, Gilstrap LC., 3rd Other factors/conditions associated with cerebral palsy. Semin Perinatol. 2000;24:196–199. doi: 10.1053/sper.2000.7052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Handel M, Swaab H, Vries LS, Jongmans MJ. Long-term cognitive and behavioral consequences of neonatal encephalopathy following perinatal asphyxia: a review. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:645–654. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0437-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bjorkman ST, Miller SM, Rose SE, Burke C, Colditz PB. Seizures are associated with brain injury severity in a neonatal model of hypoxia-ischemia. Neuroscience. 2010;166:157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maneru C, Junque C, Salgado-Pineda P, Serra-Grabulosa JM, Bartres-Faz D, Ramirez-Ruiz B, et al. Corpus callosum atrophy in adolescents with antecedents of moderate perinatal asphyxia. Brain Inj. 2003;17:1003–1009. doi: 10.1080/0269905031000110454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maneru C, Junque C, Botet F, Tallada M, Guardia J. Neuropsychological long-term sequelae of perinatal asphyxia. Brain Inj. 2001;15:1029–1039. doi: 10.1080/02699050110074178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Odd DE, Lewis G, Whitelaw A, Gunnell D. Resuscitation at birth and cognition at 8 years of age: a cohort study. Lancet. 2009;373:1615–1622. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60244-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cannon TD, Yolken R, Buka S, Torrey EF. Decreased neurotrophic response to birth hypoxia in the etiology of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:797–802. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herrera-Marschitz M, Dell’Anna E, Andersson K, Lubec G. Is perinatal asphyxia a concurrent factor for the development of neuropsychiatric syndromes with clinical onset at late age stages? Rev Chil Neuro-Psiquiatr. 1999;37:108–116. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sommer JU, Schmitt A, Heck M, Schaeffer EL, Fendt M, Zink M, et al. Differential expression of presynaptic genes in a rat model of postnatal hypoxia: relevance to schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;260(Suppl 2):S81–S89. doi: 10.1007/s00406-010-0159-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basovich SN. The role of hypoxia in mental development and in the treatment of mental disorders: a review. Biosci Trends. 2010;4:288–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cannon TD, Rosso IM, Hollister JM, Bearden CE, Sanchez LE, Hadley T. A prospective cohort study of genetic and perinatal influences in the etiology of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:351–366. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zornberg GL, Buka SL, Tsuang MT. Hypoxic-ischemia-related fetal/neonatal complications and risk of schizophrenia and other nonaffective psychoses: a 19-year longitudinal study. Am J Psychiatr. 2000;157:196–202. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dilenge ME, Majnemer A, Shevell MI. Long-term developmental outcome of asphyxiated term neonates. J Child Neurol. 2001;16:781–792. doi: 10.1177/08830738010160110201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robertson C, Finer N. Term infants with hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy: outcome at 3.5 years. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1985;27:473–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1985.tb04571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robertson CM, Finer NN. Educational readiness of survivors of neonatal encephalopathy associated with birth asphyxia at term. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1988;9:298–306. doi: 10.1097/00004703-198810000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barnett A, Mercuri E, Rutherford M, Haataja L, Frisone MF, Henderson S, et al. Neurological and perceptual-motor outcome at 5–6 years of age in children with neonatal encephalopathy: relationship with neonatal brain MRI. Neuropediatrics. 2002;33:242–248. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-36737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marlow N, Budge H. Prevalence, causes, and outcome at 2 years of age of newborn encephalopathy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005;90:F193–F194. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.057059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robertson CM, Finer NN, Grace MG. School performance of survivors of neonatal encephalopathy associated with birth asphyxia at term. J Pediatr. 1989;114:753–760. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(89)80132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wakuda T, Matsuzaki H, Suzuki K, Iwata Y, Shinmura C, Suda S, et al. Perinatal asphyxia reduces dentate granule cells and exacerbates methamphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion in adulthood. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3648. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weitzdoerfer R, Pollak A, Lubec B. Perinatal asphyxia in the rat has lifelong effects on morphology, cognitive functions, and behavior. Semin Perinatol. 2004;28:249–256. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calvert JW, Zhang JH. Pathophysiology of an hypoxic–ischemic insult during the perinatal period. Neurol Res. 2005;27:246–260. doi: 10.1179/016164105X25216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simola N, Bustamante D, Pinna A, Pontis S, Morales P, Morelli M, et al. Acute perinatal asphyxia impairs non-spatial memory and alters motor coordination in adult male rats. Exp Brain Res. 2008;185:595–601. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-1186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morales P, Fiedler JL, Andres S, Berrios C, Huaiquin P, Bustamante D, et al. Plasticity of hippocampus following perinatal asphyxia: effects on postnatal apoptosis and neurogenesis. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:2650–2662. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pulsinelli WA, Brierley JB, Plum F. Temporal profile of neuronal damage in a model of transient forebrain ischemia. Ann Neurol. 1982;11:491–498. doi: 10.1002/ana.410110509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pasternak JF, Predey TA, Mikhael MA. Neonatal asphyxia: vulnerability of basal ganglia, thalamus, and brainstem. Pediatr Neurol. 1991;7:147–149. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(91)90014-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gunn AJ, Cook CJ, Williams CE, Johnston BM, Gluckman PD. Electrophysiological responses of the fetus to hypoxia and asphyxia. J Dev Physiol. 1991;16:147–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pastuszko A. Metabolic responses of the dopaminergic system during hypoxia in newborn brain. Biochem Med Metabol Biol. 1994;51:1–15. doi: 10.1006/bmmb.1994.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Erp TG, Saleh PA, Rosso IM, Huttunen M, Lonnqvist J, Pirkola T, et al. Contributions of genetic risk and fetal hypoxia to hippocampal volume in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, their unaffected siblings, and healthy unrelated volunteers. Am J Psychiatr. 2002;159:1514–1520. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller SP, Ramaswamy V, Michelson D, Barkovich AJ, Holshouser B, Wycliffe N, et al. Patterns of brain injury in term neonatal encephalopathy. J Pediatr. 2005;146:453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barkovich AJ, Miller SP, Bartha A, Newton N, Hamrick SE, Mukherjee P, et al. MR imaging, MR spectroscopy, and diffusion tensor imaging of sequential studies in neonates with encephalopathy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:533–547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DeLong GR. Autism, amnesia, hippocampus, and learning. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1992;16:63–70. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7634(05)80052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lou HC. Etiology and pathogenesis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): significance of prematurity and perinatal hypoxic–haemodynamic encephalopathy. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85:1266–1271. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb13909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rennie JM, Hagmann CF, Robertson NJ. Outcome after intrapartum hypoxic ischaemia at term. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;12:398–407. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnston MV, Hoon AH., Jr Possible mechanisms in infants for selective basal ganglia damage from asphyxia, kernicterus, or mitochondrial encephalopathies. J Child Neurol. 2000;15:588–591. doi: 10.1177/088307380001500904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stone BS, Zhang J, Mack DW, Mori S, Martin LJ, Northington FJ. Delayed neural network degeneration after neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:535–546. doi: 10.1002/ana.21517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lodygensky GA, West T, Moravec MD, Back SA, Dikranian K, Holtzman DM, et al. Diffusion characteristics associated with neuronal injury and glial activation following hypoxia-ischemia in the immature brain. Magn Reson Med. 2011; doi:10.1002/mrm.22869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Dell’Anna E, Chen Y, Engidawork E, Andersson K, Lubec G, Luthman J, et al. Delayed neuronal death following perinatal asphyxia in rat. Exp Brain Res. 1997;115:105–115. doi: 10.1007/PL00005670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morales P, Reyes P, Klawitter V, Huaiquin P, Bustamante D, Fiedler J, et al. Effects of perinatal asphyxia on cell proliferation and neuronal phenotype evaluated with organotypic hippocampal cultures. Neuroscience. 2005;135:421–431. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bjelke B, Andersson K, Ogren SO, Bolme P. Asphyctic lesion: proliferation of tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive nerve cell bodies in the rat substantia nigra and functional changes in dopamine neurotransmission. Brain Res. 1991;543:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91041-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johansen FF, Sorensen T, Tonder N, Zimmer J, Diemer NH. Ultrastructure of neurons containing somatostatin in the dentate hilus of the rat hippocampus after cerebral ischaemia, and a note on their commissural connections. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1992;18:145–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1992.tb00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morales P, Simola N, Bustamante D, Lisboa F, Fiedler J, Gebicke-Haerter PJ, et al. Nicotinamide prevents the long-term effects of perinatal asphyxia on apoptosis, non-spatial working memory and anxiety in rats. Exp Brain Res. 2010;202:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-2103-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kohlhauser C, Kaehler S, Mosgoeller W, Singewald N, Kouvelas D, Prast H, et al. Histological changes and neurotransmitter levels three months following perinatal asphyxia in the rat. Life Sci. 1999;64:2109–2124. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(99)00160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hoeger H, Engidawork E, Stolzlechner D, Bubna-Littitz H, Lubec B. Long-term effect of moderate and profound hypothermia on morphology, neurological, cognitive and behavioural functions in a rat model of perinatal asphyxia. Amino Acids. 2006;31:385–396. doi: 10.1007/s00726-006-0393-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iuvone L, Geloso MC, Dell’Anna E. Changes in open field behavior, spatial memory, and hippocampal parvalbumin immunoreactivity following enrichment in rats exposed to neonatal anoxia. Exp Neurol. 1996;139:25–33. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hoeger H, Engelmann M, Bernert G, Seidl R, Bubna-Littitz H, Mosgoeller W, et al. Long term neurological and behavioral effects of graded perinatal asphyxia in the rat. Life Sci. 2000;66:947–962. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(99)00678-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dell’Anna ME, Calzolari S, Molinari M, Iuvone L, Calimici R. Neonatal anoxia induces transitory hyperactivity, permanent spatial memory deficits and CA1 cell density reduction in developing rats. Behav Brain Res. 1991;45:125–134. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(05)80078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lubec B, Chiappe-Gutierrez M, Hoeger H, Kitzmueller E, Lubec G. Glucose transporters, hexokinase, and phosphofructokinase in brain of rats with perinatal asphyxia. Pediatr Res. 2000;47:84–88. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200001000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Seidl R, Stockler-Ipsiroglu S, Rolinski B, Kohlhauser C, Herkner KR, Lubec B, et al. Energy metabolism in graded perinatal asphyxia of the rat. Life Sci. 2000;67:421–435. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(00)00630-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Herrera-Marschitz M, Morales P, Leyton L, Bustamante D, Klawitter V, Espina-Marchant P, et al. Perinatal asphyxia: current status and approaches towards neuroprotective strategies, with focus on sentinel proteins. Neurotox Res. 2011;19:603–627. doi: 10.1007/s12640-010-9208-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen Y, Engidawork E, Loidl F, Dell’Anna E, Goiny M, Lubec G, et al. Short- and long-term effects of perinatal asphyxia on monoamine, amino acid and glycolysis product levels measured in the basal ganglia of the rat. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1997;104:19–30. doi: 10.1016/S0165-3806(97)00131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dienel GA, Hertz L. Astrocytic contributions to bioenergetics of cerebral ischemia. Glia. 2005;50:362–388. doi: 10.1002/glia.20157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Engidawork E, Chen Y, Dell’Anna E, Goiny M, Lubec G, Ungerstedt U, et al. Effect of perinatal asphyxia on systemic and intracerebral pH and glycolysis metabolism in the rat. Exp Neurol. 1997;145:390–396. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lubec B, Dell’Anna E, Fang-Kircher S, Marx M, Herrera-Marschitz M, Lubec G. Decrease of brain protein kinase C, protein kinase A, and cyclin-dependent kinase correlating with pH precedes neuronal death in neonatal asphyxia. J Investig Med. 1997;45:284–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lubec B, Marx M, Herrera-Marschitz M, Labudova O, Hoeger H, Gille L, et al. Decrease of heart protein kinase C and cyclin-dependent kinase precedes death in perinatal asphyxia of the rat. FASEB J. 1997;11:482–492. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.6.9194529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aronowski J, Grotta JC, Waxham MN. Ischemia-induced translocation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II: potential role in neuronal damage. J Neurochem. 1992;58:1743–1753. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb10049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kretzschmar M, Glockner R, Klinger W. Glutathione levels in liver and brain of newborn rats: investigations of the influence of hypoxia and reoxidation on lipid peroxidation. Physiol Bohemoslov. 1990;39:257–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hasegawa T. Anti-stress effect of beta-carotene. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;691:281–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb26196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ikeda T, Choi BH, Yee S, Murata Y, Quilligan EJ. Oxidative stress, brain white matter damage and intrauterine asphyxia in fetal lambs. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1999;17:1–14. doi: 10.1016/S0736-5748(98)00055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tan S, Zhou F, Nielsen VG, Wang Z, Gladson CL, Parks DA. Increased injury following intermittent fetal hypoxia-reoxygenation is associated with increased free radical production in fetal rabbit brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:972–981. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199909000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Capani F, Loidl CF, Aguirre F, Piehl L, Facorro G, Hager A, et al. Changes in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in rat brain during global perinatal asphyxia: an ESR study. Brain Res. 2001;914:204–207. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)02781-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Numagami Y, Zubrow AB, Mishra OP, Delivoria-Papadopoulos M. Lipid free radical generation and brain cell membrane alteration following nitric oxide synthase inhibition during cerebral hypoxia in the newborn piglet. J Neurochem. 1997;69:1542–1547. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69041542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Berger R, Gjedde A, Heck J, Muller E, Krieglstein J, Jensen A. Extension of the 2-deoxyglucose method to the fetus in utero: theory and normal values for the cerebral glucose consumption in fetal guinea pigs. J Neurochem. 1994;63:271–279. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63010271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dell’Anna E, Chen Y, Loidl F, Andersson K, Luthman J, Goiny M, et al. Short-term effects of perinatal asphyxia studied with Fos-immunocytochemistry and in vivo microdialysis in the rat. Exp Neurol. 1995;131:279–287. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(95)90050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Johnston MV, Fatemi A, Wilson MA, Northington F. Treatment advances in neonatal neuroprotection and neurointensive care. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:372–382. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70016-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Holopainen IE, Lauren HB. Glutamate signaling in the pathophysiology and therapy of prenatal insults. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011; doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 86.Siesjö BK, Katsura K, Pahlmark K, Smith M-L. The multiples causes of ischemic brain damage: a speculative synthesis. In: Krieglstein J, Oberpichler-Schwenk H, editors. Pharmacology of cerebral ischemia. Stuttgart: Medpharm Scientific Publishers; 1992. p. 511–525

- 87.Kirino T. Delayed neuronal death. Neuropathology. 2000;20(Suppl):S95–S97. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2000.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen Z, Kontonotas D, Friedmann D, Pitts-Kiefer A, Frederick JR, Siman R, et al. Developmental status of neurons selectively vulnerable to rapidly triggered post-ischemic caspase activation. Neurosci Lett. 2005;376:166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Klawitter V, Morales P, Bustamante D, Goiny M, Herrera-Marschitz M. Plasticity of the central nervous system (CNS) following perinatal asphyxia: does nicotinamide provide neuroprotection? Amino Acids. 2006;31:377–384. doi: 10.1007/s00726-006-0372-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Klawitter V, Morales P, Bustamante D, Gomez-Urquijo S, Hokfelt T, Herrera-Marschitz M. Plasticity of basal ganglia neurocircuitries following perinatal asphyxia: effect of nicotinamide. Exp Brain Res. 2007;180:139–152. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0842-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Moroni F. Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase 1 (PARP-1) and postischemic brain damage. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Olney JW. Brain lesions, obesity, and other disturbances in mice treated with monosodium glutamate. Science. 1969;164:719–721. doi: 10.1126/science.164.3880.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Benveniste H, Drejer J, Schousboe A, Diemer NH. Elevation of the extracellular concentrations of glutamate and aspartate in rat hippocampus during transient cerebral ischemia monitored by intracerebral microdialysis. J Neurochem. 1984;43:1369–1374. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb05396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McDonald JW, Johnston MV. Pharmacology of N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced brain injury in an in vivo perinatal rat model. Synapse. 1990;6:179–188. doi: 10.1002/syn.890060210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Peeters LL, Sheldon RE, Jones MD, Jr, Makowski EL, Meschia G. Blood flow to fetal organs as a function of arterial oxygen content. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;135:637–646. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)32989-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jensen A, Berger R. Fetal circulatory responses to oxygen lack. J Dev Physiol. 1991;16:181–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Berger R, Garnier Y. Pathophysiology of perinatal brain damage. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1999;30:107–134. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(99)00009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lou HC, Tweed WA, Davies JM. Preferential blood flow increase to the brain stem in moderate neonatal hypoxia: reversal by naloxone. Eur J Pediatr. 1985;144:225–227. doi: 10.1007/BF00451945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gitto E, Reiter RJ, Karbownik M, Tan DX, Gitto P, Barberi S, et al. Causes of oxidative stress in the pre- and perinatal period. Biol Neonate. 2002;81:146–157. doi: 10.1159/000051527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mizui T, Kinouchi H, Chan PH. Depletion of brain glutathione by buthionine sulfoximine enhances cerebral ischemic injury in rats. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:H313–H317. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.2.H313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dringen R. Glutathione metabolism and oxidative stress in neurodegeneration. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:4903. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]