Abstract

This chapter aims at providing an insight into some major aspects linked to migration of medical doctors within Europe. The article describes main factors which contribute to doctors’ migration. Further, the current and future mobility trends in Europe are discussed. A major part of this chapter is dedicated to an overview of the EU legal framework impacting healthcare professionals’ mobility, followed by some useful information related to the procedures for recognition of professional qualifications and offices in charge of mobility. Finally, the impacts on healthcare systems and the policy implications of doctor’s mobility are described in context of personalised medicine.

Keywords: Personalised medicine, Healthcare promotion, European trends, EU framework, Guidelines, Professional qualification

Introduction

Medical doctors move across borders being motivated by higher salaries, better working conditions, new professional experience, and training and career opportunities. In Europe, migration of medical doctors has been observed since the 1940s and has shown various dynamics over the years. European integration has offered new possibilities for medical doctors to improve their skills, to study or to work in other countries. However, outflows from Eastern Europe started before accession, due to the political transitions of the late 1980s and the last 1990s.

The EU enlargement, first in 2004 and then in 2007, has generated increased mobility, especially from East to West, namely from EU-12 to EU-15. However, the EU enlargement did not generate outflows as initially expected. Studies have shown that migration of physicians from new Member States has been lower than the leaving intentions [1].

Given the increasing trends in health professionals’ mobility, the European Union has established a legal framework to regulate both the recognition of professional qualification and the free mobility of doctors and patients within Europe. However, a legal framework for the recognition of professional qualification for physicians willing to work outside Europe and for those coming from non-European countries is still lacking.

Migration of health professionals in generally and of medical doctors in particular has its roots in current problems of healthcare systems. Medical doctors decide to move from one country to another not only because of higher incomes, but in search of better working environments, career opportunities and social recognition. Thus, mobility of medical doctors is seen as a symptom of more fundamental health systems problems. These need to be addressed by policy makers in an integrated manner because health professional mobility cannot be considered in isolation. While some European countries have to deal with major shortages of medical doctors, other are confronted with increasing pressures to manage maldistribution, both geographically and in terms of specialities needed.

Mobility of medical doctors has both positive and negative effects on the healthcare systems. Usually the positive effects occur when mobility is temporary and with the purpose of achieving new experiences, new specialities and training, followed by return in home country. In addition, mobility of doctors impacts positively the patients’ access to medical treatment and medical service, because patients can benefit of the knowledge and training achieved by medical doctors in other countries.

If mobility is for long-term and outflows occur in countries struggling with shortages of medical doctors, then the negative impacts on the healthcare systems are felt both at macro level - financial loss for the country that has paid for the education of the physicians, national health system has to be adapted to the new situation, and at micro level – lack of sufficient medical doctors or maldistribution will impact patients’ safety and access to care, and finally patients’ health.

Driving forces for physicians mobility in Europe

Among the most-cited factors for physicians’ mobility is the financial motivation. As regards the salaries, major differences between European countries can be observed. Especially since the EU became more diverse in socio-economic terms, with larger salary differentials, incentives to seek employment in another Member State have increased. For example, an Estonian medical doctor can earn six times more in Finland while a Romanian general practitioner can earn ten times more in France. In 2009, a 25% cut in the salaries of health professionals in Romania has led to an increase in the number of doctors seeking work abroad. A reverse effect has been observed in Poland, Lithuania and Slovenia, where annual salary increases have helped to diminish the outflow of medical doctors [1].

High salary differentials exist not only between EU-12 and EU-15, but also between EU-15 and non-EU countries, such as US, New Zeeland and Australia. Therefore, many doctors from Western European countries (EU-15) may be motivated to seek work overseas.

Another factor influencing physicians to move across borders is the working environment and conditions. The economic situation of a country has a major impact on the quality and standards of healthcare facilities and on the social benefits offered for health professionals. While some European countries, mostly from EU-15, have developed high standards for healthcare such as better equipped hospitals, introduction of high technologies for diagnosis and surgery, and new tools for testing, other countries struggle with major shortages as regards the facilities named above. This is usually the case of new Member States, which had to pass through a difficult transition period and are affected by economic problems that do not leave room for further development of the existent healthcare facilities. Therefore, when medical doctors are forced to deal with a lower number of hospital beds than the number of patients, with old diagnostic tools, with shortage of medicines and instruments available in hospital pharmacies, or with inappropriate conditions for carrying out complex surgeries, they often decide to work in an environment that can offer them better conditions for doing their job.

However, better working conditions do not only refer to access to better healthcare facilities but also to social and economic incentives, working schedule and promotion opportunities.

Training and career opportunities are also among the relevant decision-making factors for physicians who consider leaving their country of origin, either temporary or for a long period of time. Again, the available training opportunities vary considerably across Europe and there are also differences between Europe and countries like US or Japan. Therefore, doctors migrate because they may wish to specialise in a certain medical filed which is not available in their country or, if available, it is not yet sufficiently developed. But doctors may seek training and career opportunities in other countries not only because such opportunities lack in their home country, but because the experience and the know-how achieved abroad is often very enriching and acts as a boost for their career. In addition, new professional and personal experiences achieved across the borders may widen their horizon in the medical field.

Finally, some medical doctors also wish to migrate because they simply want to make a change in their lifestyle. For instance, a physician from Denmark or Sweden could seek working in Spain or in Italy, because the Southern European countries are well known for their warm climate, relaxed daily life, rich culture and tasty foods. Similarly, a physician from Bulgaria could wish to work in Austria not necessarily for a higher salary but for the well organised system and infrastructure, for the Austrian high living standards or for the great mountains.

According to a WHO report on healthcare workforce migration in Europe, there are also other factors associated with migration flows that can stimulate migration and affect the choice of a destination country [2]:

Organizational factors, such as heavy workload, occupational risks, poor management, favouritism or lack of due process, lack of recognition;

Healthcare system factors, such as the absence or inadequacy of human resource policies, insufficient funding of health services, and centralised decision-making;

General environmental factors, such as poor economic conditions and lack of security.

Current trends in inflows and outflows

The mobility of doctors within the European Region was to a large extent influenced by the EU enlargement in 2004 and 2007. The EU enlargement triggered East–West asymmetries in terms of inflows and outflows of health professionals, with migrants from new Member States moving to countries from EU-15. However, many of the EU-15 countries have outflows of the same magnitude as the EU-12, but unlike the EU-15, the EU-12 countries have only negligible inflows [1].

In Europe, among the major destination countries are Germany, France, Italy, UK and Spain. They “receive” doctors from countries like Poland, Greece, Romania, Switzerland and the Czech Republic. Germany is at the same time a big source and destination country, German doctors choosing to migrate mainly to the United Kingdom and Italy, followed by Switzerland and US. Outflows have also been observed in the UK, mainly toward neighbouring countries like Ireland and France, but also to Spain and the US [2].

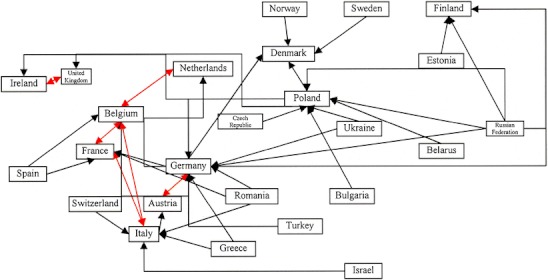

According to a WHO study on health personnel migration, the flow of migrant doctors is very dynamic in the European Region. This situation is illustrated in the Fig. 1, which shows the inflows and outflow of physicians from selected European countries [2].

Fig. 1.

Migration of physicians in the WHO European Region (red arrows indicate two-way flows), taken from [2]

In Fig. 1 one can observe not only a flow from East to West, but also a dynamic exchange between Western countries. Thus, the flow of migrant doctors among Belgium, France and the Netherlands is also multidirectional. Further, doctors from Germany, Norway and Sweden tend to choose Denmark.

Although there have been several recent studies examining the migration of healthcare workforce in Europe, data are still limited. Policy makers, workforce planners and healthcare managers need to better understand the mobility of trends in order to react with the right measures.

Legal framework for cross-border professional mobility within Europe

Due to the European integration and EU enlargement, which brought more flexibility for travelling and working in Europe, it became obvious that an EU framework for professional mobility is needed. In response to this situation, the European Parliament and the European Council adopted the Directive 2005/36/EC on recognition of professional qualifications, which affects more than 800 different professions regulated by Member States across the EU, including medical doctors, nurses, midwives, and dentists. The Directive sets the European legal framework for the recognition of professional qualifications obtained in a Member State other than the one where the person wishes to work. With Directive 2005/36/EC the EU has reformed the system for recognition of professional qualifications, in order to help make labour markets more flexible, further liberalise the provision of services, encourage more automatic recognition of qualifications, and simplify administrative procedures. The most recent consolidated version of the Directive was made available on 24 March 2011 [3].

Until 20 October 2007 when the transposition period ended, this Directive has replaced 15 existing Directives in the field of recognition of professional qualifications, providing the first comprehensive modernisation of the EU system since its introduction over 40 years ago [4].

According to the European Commission, only 22 out of 27 member States fully transposed the Directive within the given timeframe. The laggard five Member States were expected to complete the transposition in spring 2010.

Considering the complexity of Directive and the degree it impacts national legislation, some Member States had to adapt a significant number of measures in order to complete the transposition.

Directive 2005/36/EC facilitates temporary provision of services (TPS) by replacing the previous system of prior check of qualifications by the simpler, optional, system of prior declaration. However, due to the need to protect consumers, a prior check of qualifications may be maintained for professions having public health or safety implications (Article 7(4) of the Directive). According to the European Commission, 26 Member States have implemented Article 7(4) of the Directive by April 2010, apart from Greece where the situation was still unclear [4].

The Directive provides for a special scheme for temporary mobility. In such situations, professionals can in principle work on the basis of a declaration made in advance.

The Directive also applies to professionals wishing to establish themselves in an EU country other than that in which they obtained their professional qualifications, either as an employed or self-employed person, either on a permanent basis.

Directive 2005/36/EC sets out three systems for the recognition of qualifications:

- Automatic recognition for professions for which the minimum training conditions have been harmonised (health professionals, architects, veterinary surgeons).

- Basic medical training and general practitioner qualifications (Annex V.5.1.1 and V.5.1.4)

- Specialist doctors’ qualifications are automatically recognised in certain EU countries (Annex V.5.1)

The general system for other regulated professions (including non-automatic recognition - Art. 10 to 15).

Recognition on the basis of professional experience for certain professional activities.

Title II of Directive 2005/36/EC governs the recognition of professional qualifications in the context of a temporary move to the territory of another EU country. The temporary and occasional nature of the activities of a self-employed or employed person is assessed on a case-by-case basis, in light of the duration of the activity, its frequency, regularity and continuity. The Directive also includes provisions on knowledge of languages and professional and academic titles.

But the current system must be evaluated in order to verify whether full use has been made of all the opportunities offered by Directive 2005/36/EC. The system must also take account of the considerable changes that have occurred in the Member States’ educational and training systems.

For this reason, the Commission has begun working on evaluating the 2005 Directive which culminated in a Green Paper Modernising the Professional Qualifications Directive in June 2011 [5]. The public consultation on the Green Paper was launched by the Commission in January 2011 and a summary report with responses is already available [6]. The revision of the Directive is planned for 2012.

As regards specifically the mobility of health professionals, the European Commission issued a Green Paper on European workforce for Health in December 2008 and invited all interested organisation to a public consultation, which closed on 31 March 2009.

In addition to Directive 2005/36/EC addressing cross-border workforce mobility across Europe, on 9 March 2011 the European Parliament and Council adopted Directive 2011/24/EU on the application of patients’ rights in cross-border healthcare.

The Directive addresses in particular the mobility of patients seeking treatment in another Member State and introduces rules regarding the reimbursement of treatments and medical care or investigations received abroad. As regards the impact of Directive 2011/24/EU on the mobility of health professionals, the Directive stipulates that “Member States should facilitate cooperation between healthcare providers, purchasers and regulators of different Member States at national, regional or local level in order to ensure safe, high-quality and efficient cross-border healthcare. This could be of particular importance in border regions, where cross-border provision of services may be the most efficient way of organising health services for the local population, but where achieving such cross-border provision on a sustained basis requires cooperation between the health systems of different Member States” [7].

According to Directive 2011/24/EU, cooperation between Member States may concern “practical mechanisms to ensure continuity of care or practical facilitating of cross-border provision of healthcare by health professionals on a temporary or occasional basis.” However, in Directive 2011/24/EU it is mentioned that this Directive should be without prejudice to Directive 2005/36/EC on the recognition of professional qualifications. This means that free provision of services of a temporary or occasional nature, including services provided by health professionals in another Member State is not subject to specific provisions of Union law and is to be restricted for any reason relating to professional qualifications [7].

Although the mobility of doctors within the European Union is to an extent regulated by EU law, it is also necessary to take into consideration the national legislation from European Member States.

As mentioned in previous paragraphs, the existing legal framework addresses only the mobility of health professionals (and other) when they cross borders within Europe. But the migration in/from countries outside Europe is currently not regulated. Thus, if a German physician would like to work in China he/she may encounter difficulties in acquiring the recognition of his/her qualifications allowing working in this country. Or, if a physician from Georgia is seeking work in France, again, there is to date no European legal act which can help in such cases. Mutual agreements exist today but only between individual countries. Therefore, the European Union should consider introducing further regulations or developing legal instruments aiming at solving this challenge – healthcare workforce migration beyond Europe’s borders.

Besides the legislative framework aiming at regulating the mobility of doctors in Europe, the World Health Organisation developed a non-regulatory instrument on the international recruitment of health personnel - WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel. The WHO Code of Practice was adopted at the sixty-third World Health Assembly in Geneva on 21 May 2010 and its key components are:

- In destination countries:

- ethical recruitment practices;

- protection of the rights of foreign healthcare workers;

- increased education and training for health sector students;

- pairing of needs and supply.

- In source countries:

- improved conditions for healthcare professionals;

- continued medical training and increased opportunities;

- incentives to retain physicians and nurses in countries and regions with human resource shortages.

This initiative of WHO comes also in response to the consequences of the financial crisis on labour markets and addresses the need to mitigate the negative effects of migration on health systems in developing countries and “to ensure equitable access to health care services while minimizing the need to rely on the immigration of health personnel from other countries”. The resolution (EUR/RC59/R4) adopted by the Regional Committee urges Member States “to increase their efforts to develop and implement sustainable health workforce policies, strategies and plans as a critical component of health systems strengthening” and “to advocate the adoption of a global code of practice on the international recruitment of health personnel in line with the European values of solidarity, equity and participation, both within the WHO European Region and globally” [8].

Offices in charge of professional mobility and recognition of professional qualifications

In order to assist the medical doctors (and other professionals) who intend to work across borders, National Contact Points have been established at the initiative of the European Commission’s service Free Movement of Professionals, Directorate General Internal Market [9]. There are Contact Points in every EU country that can give information on the recognition of professional qualifications according to the national law and procedures to be followed. Contact Points may be Ministries of Education, Research or Science or other national institutions [10]. The Contact Points also serve as a guide for the applicants, helping them to complete the required administrative formalities.

But Contact Points can only assist the applicants with their requests and are not in charge for deciding whether the recognition of a certain profession should be granted. The “decision-makers” are the national competent authorities, who decide whether or not to recognise professional qualifications obtained in other EU countries, in accordance with European and national legislation [11]. The competent authorities in Member States are expected to use a set of common rules laid down by a Code of Conduct.

As regards the procedure to be followed for the recognition of professional qualifications, this is set out in Directive 2005/36/EC. The applicant must apply to the authority that oversees the doctor profession in that country and provide the authority with the proof of qualifications. The competent authority must acknowledge the application within 1 month of receiving it, and ask for missing but necessary documents to process the application. Then the authority assesses the qualifications and decides whether to grant the application within 3 months.

For complicated cases in the area of non-automatic recognition this procedure may last 4 months. If the applicant does not accept the decision of the competent authority, he/she can appeal to the relevant court in that country.

With the aim of ensuring better coordination both among Member States and between Member States and EC, the Commission established a Group of Coordinators for the recognition of professional qualifications [12]. The tasks of this Group include helping national authorities and the Commission work together better, monitoring policies with a bearing on qualifications for regulated professions, and exchanging experiences and good practices in the recognition of qualifications. Group’s members and alternate members are appointed by national governments and they meet several times a year. Experts and observers are invited to take part in the Group’s meetings, which are chaired by the European Commission.

Further support for workforce mobility within Europe was made available by the European Commission Directorate General on Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities, who has established EURES – the European Job Mobility Portal [13]. The purpose of EURES is to provide information, advice and recruitment/placement (job-matching) services for the benefit of workers and employers as well as any citizen wishing to benefit from the principle of the free movement of persons. There are currently over 20 EURES cross-border partnerships, spread geographically throughout Europe and involving more than 13 countries.

EURES plays an important especially in cross-border regions, areas in which there are significant levels of cross-border mobility. More than 600 000 people live in one EU country and work in another and they have to cope with different national practices and legal systems. They may come across administrative, legal or fiscal obstacles to mobility on a daily basis.

EURES advisers in these areas provide specific advice and guidance on the rights and obligations of workers living in one country and working in another. Finally, EURES helps workers to cross borders!

Impact on healthcare systems and policy implications

Without doubt, doctors’ migration influences both the source country and the recipient country. The effects can be positive, negative or a mixture of both. The impacts on the performance of health systems are subtle, meaning that they are indirect or hard to discern. But there are evident impacts on the health systems’ functioning. In some countries the outflow of even few specialists may disturb service provision. Moreover, some areas from Eastern European countries (e.g. Romanian rural areas) may be particularly vulnerable, showing some of the highest emigration rates among medical doctors and nurses [1].

For the healthcare systems in source countries emigration can contribute to a major shortage of health professionals. This can be observed in various forms, such as loss of training capacity (when trainers leave), heavier workloads for doctors’ who decide to stay or disruption of services when a key staff member leaves. In addition, the source country also loses the investment in the education of health professionals as well as the contribution they would have otherwise made for the healthcare system.

Some source countries may have also some benefits from the emigration of doctors, like reduction in staff surpluses and access to new knowledge and skills, in case the emigration is temporary. In some cases, source countries can benefit from collaborative training programmes, research projects or teaching activities which are initiated by emigrant doctors with their home country [2].

Unlike in source countries, in destination countries the benefits tend to be more obvious. For instance, migrant physicians may accept lower salaries than native ones, and they may also accept working in geographic areas avoided by national workers. In addition, available positions are filled without any cost of educating the doctors. However, destination countries may also encounter some difficulties related to inflow of medical doctors. Cultural differences may hinder communication and lack of familiarity with advanced equipment may lead to higher error rates. For temporary migrants, investment in workplace induction can be relatively high compared to the time of service provided by the migrant physicians.

As regards the policy implications of doctor’s migration, these seem to be dependent by a series of factors.

First, the uncertainties surrounding the impact of the economic crises which forced some countries to drastically reduce their healthcare budgets, while in other countries budgets remained unaffected.

A second factor impacting healthcare policies is the uncertainty of the development of healthcare workforce in Europe. According to a European Commission forecast, a shortage of around 1 million health professionals is expected that by 2020 [1].

Compensation of health workforce shortages by recruiting from third countries is to an extent restricted by ethical concerns, as stipulated in the WHO Global Code of Practice for the International Recruitment of Health Personnel adopted in 2010. For these reasons, the European countries dealing with a high demand for medical doctors will face increasing difficulties in filling their vacancies with doctors from abroad.

According to the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, there are three main sets of policy implications linked with the mobility of medical doctors [1]:

The first refers to the amount of data, intelligence and evidence, which are currently not sufficiently developed. Therefore, in the absence of inflow and outflow data, policy makers cannot take appropriate measures to manage doctors’ migration.

The second set of policy implications refers to the strengthening the general workforce strategies. It is believed that mobility of medical doctors is a “symptom” of underlying domestic workforce aspects, such as working conditions, salaries, and training opportunities.

The third policy implication is related to sustaining the re-emerging interest in workforce planning methods and techniques, by taking into account especially the dynamics and the need of healthcare force in future.

In responding to the inflow and outflow of medical doctors, today and in future, countries may take a series of measures aiming at an appropriate management of their healthcare workforce. For instance, they may sign bi-lateral agreements or facilitate the recognition of diplomas from non-European countries or they may consider developing twinning schemes and joint training programmes. Although these policy responses may facilitate a better management of doctors’ mobility, the European countries should seek to solve mainly the domestic problems liked to doctors’ migration. Thus, they should seek to strengthen existing healthcare strategies by improving retention, increasing salaries and providing more advanced training opportunities. In addition, countries could develop new healthcare strategies which can better respond to the current and future mobility trends.

References

- 1.Wismar M, Glinos IA, Maier CB, Dussault G, Palm W, Bremner J, Figueras J. Health professional mobility and health systems: evidence from 17 European countries. The Health Policy Bulletin of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. 2011; 13:1–4.

- 2.Dussault G, Frontera I, Cabral J. Migration of health personnel in the WHO European Region. Europe: WHO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Directive 2005/36/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 September 2005, on the recognition of professional qualifications, March 2011. Available at: http://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CONSLEG:2005L0036:20110 324:EN:PDF

- 4.European Commission, Scoreboard on the Professional Qualifications Directive (Directive 2005/36/EC), April 2010. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/qualifications/docs/scoreboard_2010_en.pdf.

- 5.European Commission, Green Paper on Modernising the Professional Qualifications Directive, June 2011. Available at: http://eur-ex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2011:0367:FIN:en:PDF.

- 6.European Commission, Directorate General Internal Market and Services, Public consultation on the modernisation of the Professional Qualifications Directive (Directive 2005/36/EC), Summary of responses, July 2011. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/qualifications/docs/news/20110706-summary-replies-public-consultation-pdq_en.pdf.

- 7.European Commission, Directive 2011/24/EU on the application of patients’ rights in cross-border healthcare, April 2011. Available at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2011:088:0045:0065:EN:PDF.

- 8.World Health Organisation Europe, Report on European Regional Consultation on the Draft WHO Code of Practice, Geneva, 8 December 2009.

- 9.Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/qualifications/index_en.htm.

- 10.National Contact Points. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/qualifications/contact/national_contact_points_en.htm.

- 11.Competent authorities. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/qualifications/contact/competent_authorities_en.htm.

- 12.European Commission. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/qualifications/policy_developments/group_of_coordinators_en.htm.

- 13.EURES, Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/eures/main.jsp?acro=eures&lang=en&catId=1&parentId=0