Abstract

The fields of complexity theory and nonlinear dynamic systems (NDS) are relevant for analyzing the theory and practice of Ayurvedic medicine from a Western scientific perspective. Ayurvedic definitions of health map clearly onto the tenets of both systems and complexity theory and focus primarily on the preservation of organismic equanimity. Health care research informed by NDS and complexity theory would prioritize (1) ascertaining patterns reflected in whole systems as opposed to isolating components; (2) relationships and dynamic interaction rather than static end-points; (3) transitions, change and cumulative effects, consistent with delivery of therapeutic packages in the reality of the clinical setting; and (4) simultaneously exploring both local and global levels of healing phenomena. NDS and complexity theory are useful in examining nonlinear transitions between states of health and illness; the qualitative nature of shifts in health status; and looking at emergent properties and behaviors stemming from interactions between organismic and environmental systems. Complexity and NDS theory also demonstrate promise for enhancing the suitability of research strategies applied to Ayurvedic medicine through utilizing core concepts such as initial conditions, emergent properties, fractal patterns, and critical fluctuations. In the Ayurvedic paradigm, multiple scales and their interactions are addressed simultaneously, necessitating data collection on change patterns that occur on continuums of both time and space, and are viewed as complementary rather than isolated and discrete. Serious consideration of Ayurvedic clinical understandings will necessitate new measurement options that can account for the relevance of both context and environmental factors, in terms of local biology and the processual features of the clinical encounter. Relevant research design issues will need to address clinical tailoring strategies and provide mechanisms for mapping patterns of change that account for the contiguous, self-replicating, cumulative, and synergistic theories associated with successful Ayurvedic treatment approaches.

Introduction

Nonlinear dynamic systems (NDS) theory posits that complexity is a feature of a healthy system and that with a loss of complexity comes a degradation of information processing.1–3 The nervous system exemplifies the complex nonlinear dynamic function of information distribution. Complex fluctuations are observed in the physiologic parameters of heart rate variability, respiration, and blood pressure. Disease is characterized by a regularity of pattern response indicating rigidity in the system, such as the cyclic breathing patterns characteristic of heart failure or the increasing regularity of the respiratory rate as coma deepens. Goldberger, an expert in applying complexity theory to allopathic clinical outcomes, states that “The most complex signals are generated by organisms which are in their most adaptive (healthy) states.…The complexity of a signal relates to its structural richness and correlations across multiple time scales. Complex signals are information rich.”4

Complexity has a direct connection to adaptability, such as when changes in vascular function accommodate a rapid shift from a supine to a standing posture. Complexity degrades with pathology and aging, and disease states appear to exhibit a decrease in nonlinear variability.2,4 “Pathologic periodicities” are the hallmark of certain disease states that portend diagnosis, whereas healthy biology is characterized by “correlations that extend over many scales of space or time, demonstrating a form of ‘long-range order’.”4 For instance, Goldberger makes the point that “heart rate at a particular time, is related not just to immediately preceding values, but to fluctuations in the remote past,” otherwise known as the memory effect. These theories are also consistent with the model of the immune system as a complex, adaptive system that ideally responds to different external stimuli in flexible and varied ways, rather than responding to each stimulus in a standardized and ultimately less effective manner.3 The immune system of a healthy individual recognizes viruses and responds symptomatically, while an unhealthy immune system is “stuck” and the individual may not manifest symptoms, leading to an unresponsive steady-state that is an indicator of rigidity in the system and potential breakdown.5

A key feature of nonlinear systems is that the relationship between cause and effect is not proportional, with small causes potentially leading to large effects (nonlinearity). Components of a nonlinear network interact to produce unpredictable effects, which are nevertheless “context and task dependent,” or responsive to circumstances (emergent properties).1,6 Complex nonlinear dynamics involve systems nested within systems that are interdependent, and emergent properties are influenced by environmental and processual elements. Nonlinear systems cannot be understood by analyzing constituent components individually; the components are not additive but transformative. Though nonlinear systems may behave unpredictably, they nevertheless appear to exhibit a universal set of responsive patterns, such as abrupt nonlinear transitions (bifurcations). NDS may exhibit patterns in space and time over a broad range of scales (fractal features). Fractal features imply self-similarity on multiple levels, like the self-similar anatomies of arterial and venous trees or cardiopulmonary structures serving the common physiologic function of efficient transport over a multiscale and spatially distributed system.2,4,6 Single frequencies or scales typically characterize a system in breakdown, one defined by a highly predictable pattern of behavior, or the loss of fractal complexity, such as in the aging process or frailty syndrome. Health is thus characterized by a “multi-scale, fractal type variability in structure or function.”1

Introduction to Ayurveda

Ayurveda is a 5000-year-old system of medical practice originating in India, spread by the Indian diaspora worldwide, and currently practiced and accessed by Indian and non-Indian populations alike, as part of the renewal of whole systems of medicine and the global integrative medicine movement. Ayurvedic medical practice adheres to the knowledge base found in three canonical texts: the Characka Samhita, Sushruta Samhita, and the Ashtanga Hridyayam. All streams of Ayurvedic medical practice are bound together by the continuous application of the principles and precepts found in these texts, as they are adapted to diverse environments and health care landscapes. Though their application may differ according to context, the foundational principles of Ayurveda are consistent with complexity and NDS theory as espoused in Western science. Clinical research offers an area of collective endeavor where the two paradigms can function collaboratively to improve health care delivery. In an effort to portray Ayurvedic science in terms most accessible to non-Ayurvedic health professionals, the descriptions of Ayurvedic theory that follow employ a minimal quotient of Sanskrit terminology.

Concepts of complexity theory and nonlinear dynamics

The fields of complexity theory and NDS are relevant for analyzing the theory and practice of Ayurvedic medicine from a Western scientific perspective. NDS and complexity theory focus on (1) ascertaining patterns reflected in whole systems as opposed to isolating components; (2) relationships and dynamic interaction rather than static endpoints; (3) transitions, change and cumulative effects, consistent with delivery of therapeutic packages in the reality of the clinical setting; and (4) simultaneously exploring both local and global levels of healing phenomena.6–19 NDS and complexity theory focus on therapeutic features such as nonlinear transitions between states of health/illness; the qualitative nature of shifts in health status—gradual or sudden, precarious or stable, resulting from large or small stimuli; and looking at emergent properties and behaviors stemming from interactions between organismic and environmental systems.5–11,19–21

NDS and complexity theory provide perspectives for investigating how features of internal (psychophysiologic) and external (social–environmental) health are interrelated. These interdependencies are key aspects of Ayurvedic theory. Furthermore, health as defined by Ayurveda is processually oriented and bound up with contextual factors in the clinical interaction. The individual is seen as one level of system nested within other larger systems, encompassed in continual feedback loops. Health is an emergent property of the interaction among multiple, many-layered systems. Ayurveda recognizes that the systems involved continually respond and adapt to feedback, and that there is a synergy in terms of mutual enhancement, which can occur in both positive and negative directions. This is consistent with a complex systems framework, where health can be described as multidimensional and existing on a continuum across numerous interdependent subsystems.

The individual as a complex system in Ayurveda

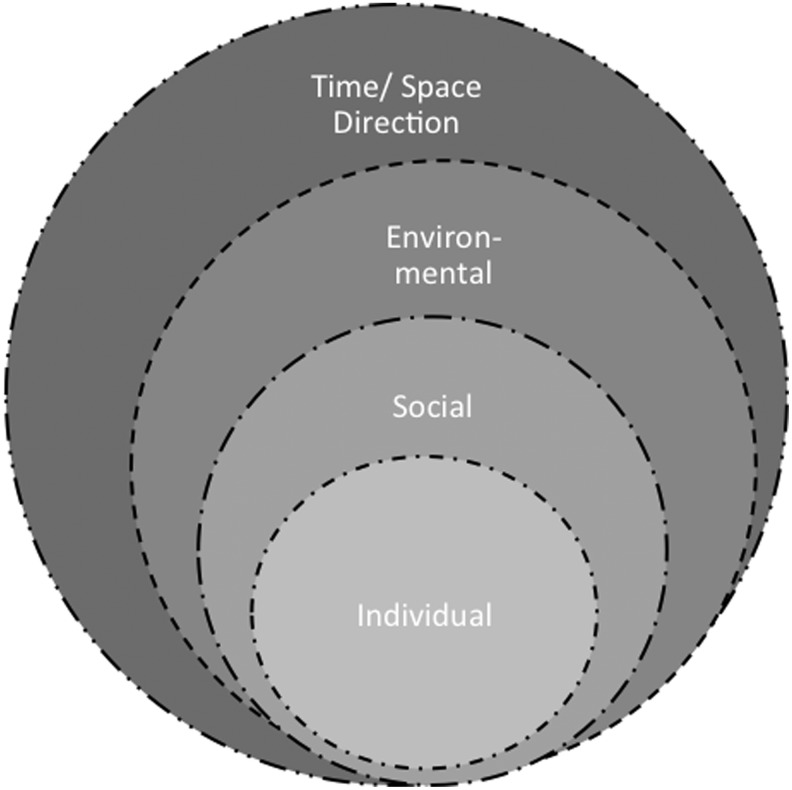

Ayurvedic definitions of health map clearly onto the tenets of both systems and complexity theory and focus primarily on the preservation of organismic equanimity.3 Ayurvedic physiology is consistent with NDS in that it is conceived as processual, involving the flow of substances and energies through networks, channels, and pathways.22–24 Ayurvedic physiology is conceived to be context-sensitive and subject to the interdependence of local and global environmental forces (Fig. 1). The contextual-processual nature of Ayurvedic physiology informs the Ayurvedic definition of health as diachronic, recognizing various subpathologic conditions that serve as precursors of disease, and providing a rubric for treating nonsymptomatic imbalances detected through pulse analysis and behavioral cues. Due to the centrality of the constitution/disequilibrium paradigm (described in detail below), Ayurvedic treatment is tailored to the individual, the nested contexts in which they live, their age, environmental features such as climate and season, and their innate capacity for resilience, adaptation, and transformation. These innate capacities are further mediated by psycho-emotional repertoire, social context, and depth of disease. Ayurvedic constitutions are associated with psychobehavioral features and coping styles. Constitutions are considered as indicators that individuals will possess certain predetermined affinities, proclivities, tendencies, and attractions. The centrality of psychobehavioral features within the constitutional rubric dictates the centrality of behavior modification and changes in diet, lifestyle, and daily routine as core Ayurvedic therapeutic categories.

FIG. 1.

The nested interdependent spheres of the individual as a system. They are porous, with information and substance flowing multidirectionally and mutually affecting input and output on local and global scales.

Ayurvedic meta-theory, cosmology, and constitutions

Ayurveda is a humoral system of medicine, meaning it employs categories of binary opposites to define and guide the treatment of disorders in the body, mind, and spirit designed to enhance the process of transformation at both deep and superficial layers.25 According to Ayurvedic cosmology, the universe, nature, and the human body are all comprised of five interdependent elements: space, air, fire, water, and earth. Space, time, and direction are subtle elements that provide the context for expression of the five gross elements at the interacting levels of the human being and their environment. The five gross elements combine in different pairs to comprise the three doshas of vata (air+space), pitta (fire+water), and kapha (water+earth). Dosha is a term that characterizes the combined material and subtle properties that create the energetic underpinnings and substance of the body–mind, supportive when in balance and problematic when aggravated. The five elements inform the doshas, which are constantly being influenced by interaction with internal and external environments.26 The human being, by cultivating a vital body and mind, can likewise transform elements and influences with a disruptive nature and neutralize or transmute them through metamorphosis (Rioux J, PhD dissertation, 2002). Dosha is sometimes translated as “that which can be vitiated,” indicating that all substances and energies are prone to imbalance. Though the word “humor” is often used to refer to the doshas, translating dosha literally as a humor runs the risk of confining its meaning to the material realm and thus impoverishing its overall physiologic and psychospiritual role. Doshas are simultaneously material and energetic, structural, functional, and integrative. When doshas are balanced, their nature is to serve an integrative function and to be materially and energetically supportive of the biopsychosocial well-being of the individual. When the doshas are aggravated, by internal or external factors that increase their expression—either qualitatively or quantitatively—they are in excess of their natural state and lead to disequilibrium for the individual. Disequilibrium is the starting point for symptomatic expression and the initiation of disease.23,24

According to Ayurvedic theory, each individual is endowed with a constitution (prakruti) at the time of conception, which is a proportionate expression of the three doshas of vata, pitta, and kapha. Constitutional assessments are typically described in quantitative form, which demonstrates the primary, secondary, and tertiary doshas of a particular individual (i.e., pitta 3, kapha 2, and vata 1). This proportionate distribution of vata, pitta, and kapha forms the baseline for equanimity and disorder for the individual's lifetime. The constitution is informed by the constitutions of the parents, the internal physiologic and psycho-emotional environment of the mother, and other factors such as climate, season, and quality of relationships.23,24 Each humor is associated with a set of qualities that are related to the elements that comprise it (Table 1). A particular individual may manifest more or less of each quality, which will contribute to their physiologic and psycho-emotional propensities, as well as the disorders to which they may be prone. Factors that may contribute to disorder throughout the lifespan include diet, lifestyle, daily routine, sleep and other habits, work, relationships, climate, season, feeling states, trauma, and degree of innate resilience versus vulnerabilities within the individual as a functional system.27–29

Table 1.

List of Qualities Associated with the Ayurvedic Doshas

| Vata−Space+Air | Pitta−Fire+Water | Kapha−Water+Earth |

|---|---|---|

| Light | Hot | Heavy |

| Cold | Sharp | Slow |

| Rough | Flowing | Dense |

| Dry | Light | Thick |

| Clear | Liquid | Dull |

| Agitated | Aggressive | Cold |

| Subtle | Penetrating | Soft |

| Dispersing | Smooth | Cloudy |

| Mobile | Unctuous/oily | Sticky/damp |

Ayurvedic humoral medicine: The doshas and the science of quality expression

According to Ayurvedic philosophy, the three doshas are in constant interaction with the expressed qualities of the internal physiologic environment and the external physical, natural, and social environment.26 All features of the internal and external environments are interrelated and in continuous dialogue and negotiation. They are eventually embodied in the behaviors, dispositions, proclivities, and affinities of the individual, in either healthy or unhealthy manifestation. When the original balance of the doshas is disturbed or increased, or they leave their natural locations in the body and “leak out” into other tissues, then the individual experiences disequilibrium (vikruti). According to the constitution of the individual, certain qualities and elements will aggravate the doshas, when they are in excess of the baseline.23,24 The aim of the clinician is to pacify aggravated doshas, focusing on the functional relationships between them and their symptom manifestation, but always attempting to locate the root cause of the imbalance.

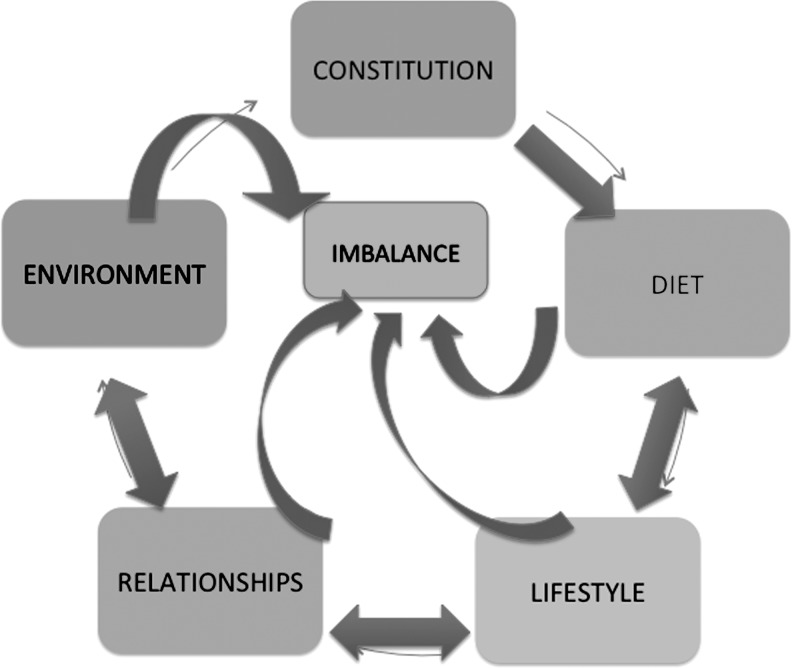

The Ayurvedic physician sifts through strata of objective data (pulse/tongue analysis and other embodied signs) and subjective information (patient experience and narrative) to peel away layers of imbalance, first by addressing physical symptoms, then psycho-emotional disorders, and finally investigating the spiritual health of the individual (right action and quality of relationships). The differential between the baseline constitution and the proportionate aggravation of the doshas serves as a quantitative and qualitative treatment algorithm, guiding the development of the therapeutic regimen. Ayurvedic clinicians may employ both the law of similars (homeopathy) and the law of dissimilars (allopathy) when treating patients, accessing whichever offers more transformative potential.23,24 Each dosha is associated with the set of qualities indicated in Table 1, which the practitioner evokes and applies selectively for therapeutic purposes. Food, drink, herbs, oils, times of day, forms of exercise, sleep habits, and emotional states, among others, are all associated with certain qualities and are applied according to highly elaborated therapeutic constructs with simple foundational precepts.27,28,30 Intervention in any of these areas may provide the spark for systemic change. Ayurveda uses cognitive reframing and a focus on instilling empowerment and self-responsibility in the patient to create a supportive environment for change (Rioux J, PhD dissertation, 2002). Relevant Ayurvedic outcomes reflect the multilayered and contextual nature of the diagnostic and therapeutic process, encompassing physiologic function; psycho-emotional outlook and self-awareness; relationship dynamics; right action and well-being; and contentment, meaning, and purpose (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

The relationships among the patient's constitution and their diet, lifestyle, daily routine, and environment. The patient's constitution is the one permanent feature that informs psycho-emotional behavior patterns. There is bidirectional feedback across the realms of activity, which affect each other and inform the imbalance of the individual, but do not impact the original constitution.

Recursive feedback loops: Environment, patient, practitioner

Local biology is an important concept for Ayurvedic practice. Ayurvedic theory asserts that the individual is engaged in a process of positive habituation, or adaptation, to localized features of the natural world, and features of interpersonal and intrapersonal behavior. Lived experience influences individual engagement with the world, which in turn, affects bodily processes, bodily disposition, and social and cultural responses to physical sensations and mental states.25,29–31 The Ayurvedic practitioner needs to be attentive to a patient's local biology in order to effectively tailor treatment for maximum therapeutic impact. Likewise, Ayurveda encompasses the idea that human beings and the natural world are inextricably interconnected and that these relationships and associations form the basis of health, or the catalysts for the development of disease. This concept, referred to as physiomorphism, supports the Ayurvedic precept that mind, body, and environment are contiguous and constantly exchanging not only information, but substance in the form of qualities.32–34 Ayurvedic practitioners conceptualize people as cold/hot, hard/soft, light/heavy in both psychologic and physiologic senses, and these qualitative expressions impact health, well-being, and the development of disease.

In Ayurvedic medical science, the five senses serve as pathways for both disruptive input leading to imbalance and therapeutic input pivotal to treatment and maintenance of a healing trajectory. Just as the senses are central to preventing illness and maintaining health, they play a key role as possible causal mechanisms and in the delivery of treatment packages. Ayurvedic theory states that not only food, but also sensory input and experience must be digested, metabolized, and eliminated according to the innate capacity of the individual to tolerate such stimulus, the rate of innate sensory metabolic activity, and any compromise in this metabolism brought on by disruption to the nervous system or vitality of the individual.23,24 The central role of the senses in influencing health status is framed in Ayurveda according to an ethic of appropriate use.29,30 This includes level and magnitude of input according to constitution and imbalance; degree of current physiologic and psycho-emotional toxicity; and type of disorder being treated. Sensory stimuli received by the clinician's five senses are also crucial—not just how the patient looks, but how they sound and smell, and the patient's subjective experiences of touch and taste—filtered through Ayurveda's analytic rubric, thereby informing diagnosis and prognosis.

Health according to Ayurveda: Microcosm mirrors macrocosm

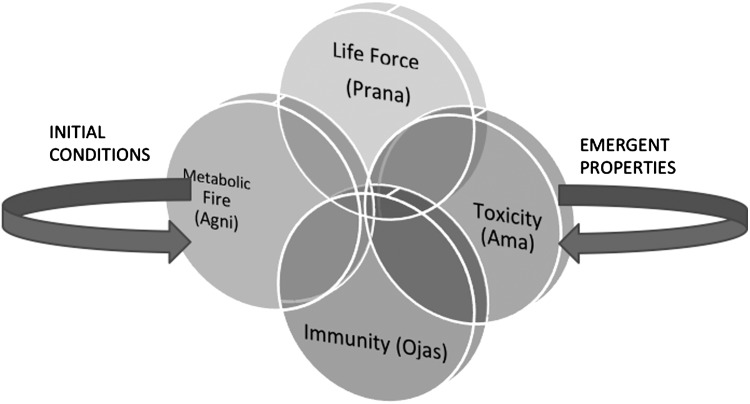

A state of health according to Ayurveda permeates all layers of the individual's experience. The healthy individual is in a positive state of functional interaction in all relevant contexts. Relevant contexts may include the molecular/genetic level, the level of the cells, organs, and senses, the interpersonal level (in terms of their work and social roles) and harmony with self, nature, and the built environment (Rioux J, PhD dissertation, 2002). Five (5) core concepts related to the Ayurvedic definition of health are the vital life force (prana), the metabolic fire (agni), the material essence of immunity/vitality (ojas), elimination of bodily waste (mala), and toxicity (ama). The life force circulates throughout the body and takes physical form in the breath and informs the vitality/immunity of the individual. Metabolic fire exists in the digestive tract, in the mind, tissues, vital and sensory organs, and at a cellular level, allowing all to function optimally. When metabolic fire operates in a supportive manner, it stabilizes both physiologic and psychologic processes to maximize the adaptive response of the individual, thereby avoiding disequilibrium and compromise of the immune system.23,24 Elimination of waste according to Ayurvedic precepts is dependent on proper functioning of metabolic fire and life force and prevents build-up of toxicity in the bodily tissues and the psycho-emotional realm. It is considered central to maintaining good health, as toxicity in the body–mind is viewed as a key contributor to disequilibrium and disease.29

Adaptation, modulation, transformation: The therapeutic process

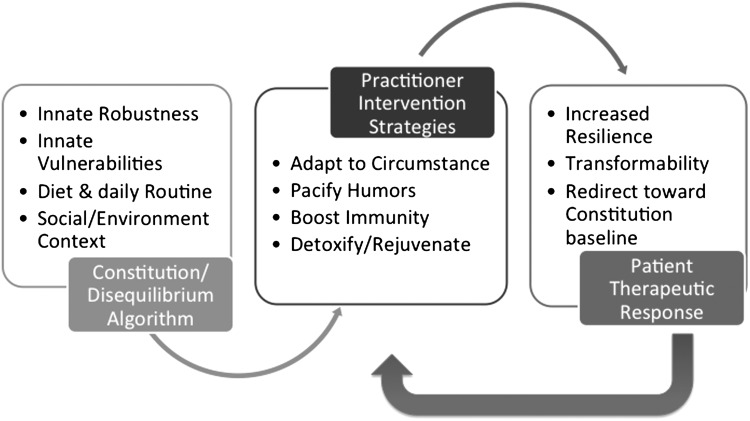

Ayurvedic diagnosis and treatment are iterative processes. The same principles and precepts are repeatedly invoked by the practitioner, and analysis and assessment of the doshas and their qualities is repeated over and over at multiple scales and levels of complexity. The simplest rules that apply at the most basic level also apply at increasingly higher levels of complexity. The same is true of scale: Principles that apply at the most local or smallest scale also apply at the most global or largest scale. This network of variables resonates with one another, mutually influencing transitions and shifts through associative connections. Practitioners look for correspondences both within and between the levels, and these correspondences guide therapeutic action and strategy (Fig. 3). Some of the key concepts that constrain and guide clinician behavior are the following capacities of the individual patient: (1) Resilience/Robustness: how well the system can absorb disturbance, reorganize while undergoing change, and maintain effective function3,7,9,19,20; (2) Adaptability: potential for ease of change in elements of the system to influence resilience3,7–10,12,20; (3) Modulation/Calibration: shifts in system structure and input that reorient function and output in an effort to adapt to contextual factors3,6,7,21; and (4) Transformability: potential for creating a fundamentally new system when environmental influences make the existing system untenable.3,7,19 These concepts are related to, and influence, the occurrence and frequency of critical fluctuations. Critical fluctuations denote “sudden disturbance and increased variability in system behavior before reorganization.”6,35

FIG. 3.

Practitioner diagnosis within the spectrum of the constitution/disequilibrium paradigm informs intervention strategies, which are enacted with the goal of enhancing resilience, adaptation, and transformability. Patient response to treatment then funnels back into the treatment algorithm, as the practitioner focuses on critical fluctuations.

According to Ayurveda, resilience is both innate—by constitution—and conferred by appropriateness of diet, lifestyle, relationships, and environmental factors. Certain constitutions possess more inherent robustness, but therapeutic interventions aimed at maximizing robustness, (i.e., rejuvenation therapy [rasayana]), are also initiated by the practitioner. Adaptability denotes that there is flexibility and creativity in the system on physiologic and psycho-emotional levels. Through adaptation, the organism learns to modify itself in response to its environment and unexpected health challenges. Calibration/Modulation happen at the level of the patient, as well as serving as guiding precepts for therapeutic intervention. The patient modulates to changes in internal and external environmental factors. The practitioner creates a rubric of these and then accesses foods, herbs, yoga poses, and so on that will facilitate recalibration of the patient back toward the original constitution, as determined by pulse reading and analysis and other corporeal signs. Transformability can be instigated at either the internal or external level, by either the patient or the practitioner. The three preceding factors pave the way for transformation, yet it can take place without them by virtue of organismic innovation. It is invoked by both subtle and material therapies and may catalyze change within the psycho-emotional realm that then funnels into physiologic change, or vice versa, either over time or suddenly.

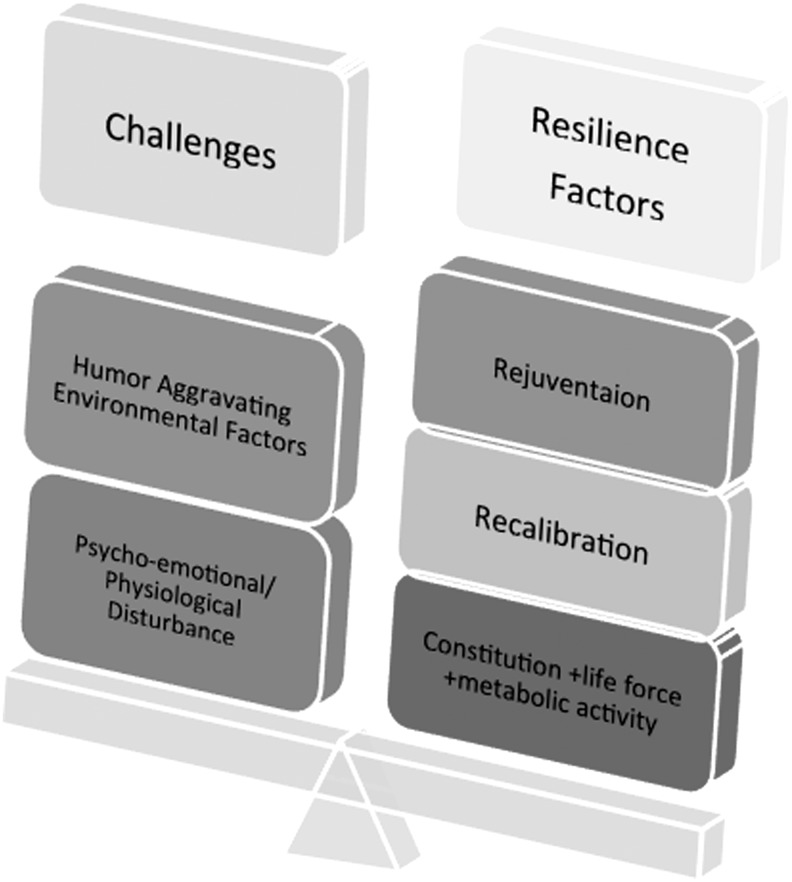

Critical Fluctuations are key in alerting practitioners, and potentially researchers, to therapeutic thresholds, in which a critical mass of healing impact has been achieved, indicated by an imminent change in one of the five layers of matter (koshas), from gross to subtle: (1) material/physical; (2) vital/physiologic; (3) sensory/perceptual; (4) cognitive; or (5) psychospiritual. The practitioner identifies the immanent approach of therapeutic thresholds by reading patterns of quality expression in the patient and doshic shifts exhibited by the body–mind. Layers 1 to 3 may be read through the symptoms of the body, while layers 3 to 5 (with some overlap) represent the realms of potentiality and are discernible through more subtle forms of diagnosis. Subtle forms of diagnosis may include pulse reading and discriminating awareness of psychosomatic patterns and signs, according to the rubric of the doshas.23,24 When the organism-as-system is destabilized, it becomes “open to new information and to the exploration of potentially more adaptive associations and configurations.”35:p716 A new state is achieved that is continually dynamic, but comparatively more stable, and characterized by less variability. Critical fluctuations often indicate transition points, and thus, if located, can present an opportunity for crucial data collection on predictors, mediators and mechanisms of change (Fig. 4).5

FIG. 4.

Organismic equanimity according to Ayurveda posits the individual as an adaptive learning organism. The scales show the process through which the patient-as-system approaches a tipping point or healing threshold. The practitioner weighs physiologic and environmental challenges to the system against the innate resilience of the patient and combines this with therapeutic interventions that will recalibrate the system and infuse it with vitality.

Tipping points and therapeutic thresholds

Phases of change create transitions and eventually tipping points, which indicate a significant shift.13 In Ayurvedic treatment, it is in these transitional phases that the individual crosses over a therapeutic threshold and is transformed, entering a new status. These transformations can take on positive or negative characteristics and the end result will depend on the interaction between individual and environment as influenced by time, space, and contextual factors.7–9,12,21 By accessing intersecting global and local levels of analyses, in both the diagnosis and treatment process, the Ayurvedic clinician simultaneously encompasses a broad span of knowledge about interactive transitions within the system as a whole. In treatment, the emphasis remains on sustaining a spectrum of actions on multiple interdependent subsystems of the individual, at numerous points in time, and in relation to context.1,2,4,6,10,11,20,22,26 The clinician must employ the perspectives of mutual and bidirectional causality, which entail the possibilities of multiple causes and multiple potential manifestations.19 In enacting the Ayurvedic paradigm, the clinician assesses patterns of correspondence between and across embodied qualities, thereby creating a map of past, present, and future disease trajectories within a larger environmental framework. Encouraging transformation, through recalibrating practices that enhance robustness and adaptability, is the role of the clinician. The clinician reads the signs of life force (prana), metabolic fire (agni), immunity (ojas), waste elimination (mala), and toxicity (ama), to contextualize the diagnostic and prognostic processes and create a therapeutic intervention aimed at restoring baseline equanimity.23,24 Clinicians also direct attention to recognizing points of reverberation, where they can locate the persistence of a particular effect that echoes on multiple levels.

Implications for Ayurvedic Research

Ayurvedic research as nonlinear, dynamic process

Complexity and NDS theory demonstrate promise for enhancing the suitability of research strategies applied to Ayurvedic medicine. The most salient concepts include (1) Sensitivity to initial conditions, where small inputs can have large effects or vice versa.1–3,6–11,19–21 This is relevant for the application of therapeutic similars/dissimilars as they intersect with baseline constitution and states of disequilibrium; (2) Emergent properties, in which complexity develops from the interaction of multiple simple parts.1–4,6–12,15,19,20 The simple manifestation of the qualities at one level or context is exponentially complicated by an expression of similars/dissimilars within another level or context; and (3) Fractals, in which repeating, self-similar patterns occur over multiple spatial and temporal scales.1,2,4,6–8,18,19 In Ayurvedic diagnosis and treatment, the expression of qualities occurs over and over—across time and in various sites, within the organism and its environment—to create the past, present, and potential future map of individual health status. Clinician strategy involves taking into account multiple flows of information and systemically recalibrating the patient through a synergistic treatment package. Patients with compromised life force, poor immunity, weak metabolic fire or toxicity (initial conditions) may be more or less sensitive, thus providing parameters for the magnitude and orientation of practitioner intervention. The simple chart of qualities associated with the humors suddenly becomes complex and intricate when approached at multiple levels of scale and through multiple, interdependent manifestations (emergent properties) (Fig. 5). Given the propensities of the constitution and how they influence individual behavior and interaction with the environment, it is evident that a fractal process is at work in terms of aggravation of the doshas on multiple levels of scale, all of which are in constant exchange, resulting in patterns of co-incidence. The centrality of package treatments in Ayurvedic practice is in conflict with the research criterion standard of the single-entity, randomized, controlled trial. In the Ayurvedic paradigm, multiple scales and their interactions are addressed simultaneously (fractals), necessitating data collection on change patterns that occur on continuums of both time and space, viewed as potentially contiguous, self-replicating, cumulative, and/or complementary, rather than isolated and discrete.

FIG. 5.

The key components of health according to the Ayurvedic paradigm are overlapping and interrelated in the diagnostic and treatment realms. The practitioner considers initial conditions such as constitution, diet, relationships, social and physical environment, and anticipates emergent properties resulting in these same spheres as a result of treatment. Appropriate intervention strategies simultaneously address function in all areas and highlight the interdependence of the functional realms, recognizing that the state of the doshas provides the contextual ground for the physiologic expression of the key elements, both in terms of original constitution and transient imbalances manifest in each individual.

The agenda for complex, systems research on Ayurvedic medicine

Current research on Ayurveda includes limited clinical trials. Existing clinical studies have relatively small sample sizes. Ayurvedic research protocols have not been standardized, making comparability across studies challenging. Although prior Ayurvedic research protocols have been faithful to Ayurvedic principles in treatment conceptualization and design of the intervention, data collection methods have not accounted for features of tailoring or Ayurvedic outcomes. Additionally, data analysis and reporting strategies have not accounted for measuring Ayurvedic process and have failed to address causal mechanisms. More importantly, typical techniques used to evaluate the quality of Ayurvedic research are inappropriate for whole systems of medicine or medical paradigms that utilize package treatments. Meta-analyses of Ayurvedic research have not utilized evaluation criteria relevant for clinical care that involves complex systems treatment practices. New research tools and analytic strategies are needed to investigate patient-level shifts during treatment and clinical outcomes relevant to Ayurvedic practitioners. Some of the therapeutic strengths of the Ayurvedic paradigm on which research efforts could focus include many of the chronic and “lifestyle” illnesses influenced by stress, diet, daily habits, and environmental factors. One fruitful area of research on Ayurvedic clinical care may be comparative effectiveness research. Patient outcomes resulting from an Ayurvedic clinical intervention can be compared with patient outcomes in a control group receiving conventional biomedical treatment for the same condition, collecting and comparing shared outcome measures. In addition, it is important to identify the unique processes associated with tailored interventions within the Ayurvedic clinical framework. These may include specific styles of implementing patient education, empathic communication, cognitive reframing methods, the substance of the therapeutic relationship, or foundational concepts related to self-empowerment and self-awareness.

Coincident with collection of clinical data on patient outcomes, research on causal mechanisms in Ayurvedic healing is pivotal. Mechanistic research can be conducted using the lens of systems biology, and in dialogue with the concepts of complexity and NDS, given their consistency with Ayurvedic traditional science.7,8,10,20,36 Two (2) types of outcomes should be delineated: those that align with the therapeutic intentions of practitioners and are consistent with the theoretical underpinnings of Ayurvedic science, as well as those that are biomedically defined. Explicit inclusion of Ayurvedic theories of diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis in research studies will fortify the scientific enterprise. Serious consideration of Ayurvedic clinical understandings will necessitate new measurement options that can account for the relevance of context and environmental factors, in terms of local biology as well as the conduct of research.37–40

Relevant research design issues will need to address clinical tailoring strategies and provide mechanisms for mapping patterns of change that account for the contiguous, self-replicating, cumulative, and synergistic theories associated with successful Ayurvedic treatment approaches. A complex, systems approach will allow researchers to account for the spatial and temporal features of the healing trajectory in a way that accurately represents clinical realities.41,42 This will facilitate the development of relevant assessment criteria and treatment protocols that are simultaneously sufficiently standardized and sufficiently flexible. Flexibly standardized protocols may allow for differential application among practitioners, while adhering to immutable precepts that inform the core principles of Ayurvedic practice. It will be necessary to account for interpractitioner variability in both the assessment and treatment phases of the therapeutic process. In order to obtain data that are simultaneously scientifically interpretable and clinically relevant, it will be crucial to develop stratified inclusion criteria by constitution, imbalance, and disorder subtyping. Research methodologies that address more complex temporal measurement will be essential. This will not simply mean capturing data at more points in time, but identifying those periods of time at which critical fluctuations, tipping points, or therapeutic thresholds are likely to occur and capturing data during these phases of treatment.35 These innovations will present crucial choices in terms of which data to collect and will present challenges in terms of minimizing participant burden.

Research on the tailoring process will be essential for guiding selection of clinical interventions and outcome measures that will lend themselves to comparative effectiveness research and illumination of possible causal mechanisms. It will be critical to demonstrate the impact of tailoring on treatment, prognosis, and resolution of illness throughout the therapeutic process. Research on Ayurvedic medicine must account for outcomes that are definitional to Ayurvedic medical practice, not always associated with isolated curing events or symptom removal, but focusing on addressing root causes of disease. Measurable events key to the process of Ayurvedic treatment include critical fluctuations and tipping points, as well as quantitative and qualitative depictions of context, resilience, and adaptability. However, it is equally important to design research that has the capacity to capture overall benefit. Research on overall benefit would attempt to capture interdependent relationships between the various indices of health according to Ayurveda, the various levels of scale, and any areas of synergy or self-replicating phenomenon that create an exponential therapeutic effect.19,21 Appropriate Ayurvedic outcomes recognize the interrelated features of the body–mind and the constant interplay between the five elements, the three doshas, the five layers of matter, and the five key components of health, within the individual and between the individual and the environment. Outcomes will look at improvements in physiologic, psycho-emotional, social, and contextual measures, capturing the resonance between layers of change. Initial conditions, emergent properties, fractal patterns, and critical fluctuations are key processes pivotal to impacting overall benefit. Enhanced resilience, adaptability, and transformative potential are key indicators of overall benefit.

Conclusions

Optimal research would focus on measuring well-being and healing transitions, on both global and local levels of scale. Research that translates Ayurvedic clinical strategies into systems biology terms, or reframes Ayurvedic bench science into the language of epigenetics, can potentially demonstrate mechanistic action within the context of local biology and map the trajectories of the organism/environment feedback loop. The field of epigenetics, which focuses on gene regulation as it is affected by organism/environment interactions, is poised to demonstrate many productive areas of overlap and intersection with Ayurvedic medical theory.43–46 Outcomes-based research in Ayurveda will be critical for advancing not only dialogue across paradigms, but also collaborative clinical work between medical disciplines—truly integrative medicine. Comparing and contrasting systems biology concepts with traditional Ayurvedic medical philosophy is a fruitful way to increase understanding of Ayurvedic science from the perspective of complex, systems theory. Appropriately conducted Ayurvedic research will maximize patients' therapeutic options and encourage collaboration, knowledge exchange, and mutual respect for diverse medical expertise (Table 2).

Table 2.

Key Concepts Associated with Ayurvedic Medicine

| Constitution (Prakruti) | Physiologic and psycho-emotional proclivities and tendencies associated with the behaviors and vulnerabilities of the individual. |

| Disequilibrium/imbalance (Vikruti) | Qualitative and quantitative movement away from the baseline constitution. |

| Humor (Dosha) | Composite material and energetic entity comprising predesignated pairs of elements, associated with manifestation of certain qualities in the body–mind, both positive and negative. Aggravation of the humors is the root cause of disease. |

| Subtle life force (Prana) | Conceptually—the source of vitality. Its material form is the breath. |

| Material life force (Ojas) | Associated with immunity and the magnitude and quality of resilience available to the individual. Also related to constitution, condition of life force, metabolic fire, and toxicity. |

| Metabolic fire (Agni) | Functional rate of metabolic activity existing in digestive tract, tissues, organs, and senses. Variable according to diet, environmental factors, psychosocial factors, age, and toxicity. A key element contributing to health status, interfered with by toxins in the body. Can be stoked by invoking subtle or material life force. |

| Waste (Mala) | Mala includes sweat, urine, and feces. Consistent and complete elimination of waste products is considered a primary condition for health in Ayurveda. The body's capacity for waste elimination is impacted by other key components, such as life force (prana) and metabolic fire (agni). In the absence of proper waste elimination, toxicity (ama) will accumulate in the body–mind and disequilibrium will ensue. |

| Toxicity (Ama) | Quality and magnitude of toxic matter and energy in the body. Can exist in the digestive tract, tissues, organs, senses, and in the psycho-emotional self. Key factor contributing to disease, mediated by strength of metabolic fire, life force, and immunity. |

| Rejuvenation (Rasayana) | To revitalize through specific therapeutic measures aimed at maximizing robustness, adaptability, transformability, and effective systemic recalibration in the individual. These processes are undertaken using the constitution as a foundation and in dialogue with the condition of life force, immunity, metabolic fire, and toxicity. |

| Sheaths/layers of matter (Koshas) | Five layers of matter, from gross to subtle, that comprise the body–mind according to Ayurveda. They account for the interrelationships between the environmental, physiologic, psycho-emotional, and spiritual realms of experience and activity. |

| Physiomorphism | Emphasizes the human–nature exchange, drawing attention to the physiologic and psychologic assimilation of properties found in the external world. Features of the environment thus become embodied. |

| Local biology | Reflects tenets of biophilia by emphasizing the connections between human beings and place. Recognizes the integral role of local foods and local medicinal plants as part of traditional health promotion. Invokes the nesting of individual and environment as symbiotic and engaged in bidirectional feedback. |

| Resilience/robustness | A combination of both constitutionally innate resilience and shifting properties of resilience affected by circumstance, life stage, and environmental and psycho-emotional factors. These determine how well the system can absorb disturbance, reorganize while undergoing change, and maintain effective function. |

| Adaptability | Denotes flexibility and creativity within the system, and influences the potential for features of the system to impact resilience. |

| Modulation/calibration | An activity engaged in autonomically by the individual, as well as the key therapeutic activity of the Ayurvedic clinician. Catalyzing or implementing therapeutic principles in mutually enhancing combinations so as to shift system structure, reorient input/ output cycles, mitigate manifestation of negative qualities, and maximize qualities that will encourage baseline equanimity. |

| Critical fluctuations | Sudden disturbance and increased variability in system behavior before reorganization. Indication of transitional phases and therapeutic thresholds, indicating that a critical mass of healing impact has been achieved by delineating and imminent change of state. Associated with tipping points. |

| Transformability | The potential for the creation of an entirely new system when internal and/or external environmental influences make the existing system untenable and create the need for change. |

Disclosure Statement

No financial conflicts exist.

References

- 1.Goldberger AL. Moody GB. Costa MD. PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet. Tutorial: Variability vs. Complexity. Jan 24, 2012. http://physionet.org/tutorials/cv/ [Feb 1;2012 ]. http://physionet.org/tutorials/cv/

- 2.Goldberger AL. Complex systems. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;2:467–472. doi: 10.1513/pats.200603-028MS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berntson G. Cacioppo J. Handbook of Psychophysiology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007. Integrative physiology: Homeostasis, allostasis and the orchestration of systemic physiology; pp. 433–452. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberger AL. Nonlinear dynamics, fractals, and chaos theory for clinicians: Implications for neuroautonomic heart rate control in health and disease. Circulation. 2000;23:e215–e220. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koithan M. Verhoef MJ. Bell IR, et al. The process of whole person healing: “Unstuckness” and beyond. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13:659–668. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.7090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guastello S. Liebovitch L. Introduction to nonlinear dynamics and complexity. In: Guastello S, editor; Koopman M, editor; Pincus D, editor. Chaos and Complexity in Psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008. pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahn AC. Nahin RL. Calabrese C, et al. Applying principles from complex systems to studying the efficacy of CAM therapies. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:1–8. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahn AC. Tewari M. Poon CS. Phillips RS. The clinical applications of a systems approach. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahn AC. Tewari M. Poon CS. Phillips RS. The limits of reductionism in medicine: Could systems biology offer an alternative? PLoS Med. 2006;3:e208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell IR. Mary K. Models for the study of whole systems. Integr Cancer Ther. 2006;5:293–307. doi: 10.1177/1534735406295293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell IR. Caspi O. Schwartz GE, et al. Integrative medicine and systemic outcomes research: Issues in the emergence of a new model. Arch Intern Med. 2002;28:133–140. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bar-Tam Y. Dynamics of Complex Systems. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 2003. Overview: The dynamics of complex systems. Examples, questions, methods and concepts; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Capra F. The Web of Life: A New Scientific Understanding of Living Systems. New York: Anchor Books; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laslo E. The Systems View of the World: A Holistic Vision for Our Time. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ritenbaugh C. Fleishman S. Boon H. Leis A. Whole system research: A discipline for studying complementary and alternative medicine. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9:32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verhoef MJ. Koithan M. Bell IR, et al. Whole complexity and alternative medical systems and complexity: Creating collaborative relationships. Forsch Komplementarmed. 2012;19(suppl 1):3–6. doi: 10.1159/000335179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verhoef MJ. Lewith GT. Ritenbaugh C, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine whole systems research: Beyond identification of the inadequacies of the RCT. Complement Ther Med. 2005;13:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.West B. Where Medicine Went Wrong: Rediscovering the Path to Complexity. Hackensack, NJ: World Scientific Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimmerman B. Lindberg C. Plsek P. Edgeware: Insights from Complexity Science for Health Care Leaders. 2nd. Irving, TX: VHA Inc.; 2001. p. 271. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bell IR. Koithan M. Pincus D. Methodological implications of nonlinear dynamical systems models for whole systems complementarity and alternative medicine. Forsch Komplementarmed. 2012;19(suppl 1):15–21. doi: 10.1159/000335183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koithan M. Bell IR. Niemeyer K. Pincus D. A complex systems science perspective for whole systems of complementary and alternative medicine research. Forsch Komplementarmed. 2012;19(suppl 1):7–14. doi: 10.1159/000335181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hankey A. Ayurvedic physiology and etiology: Ayurvedo Amritanaam. The doshas and their functioning in terms of contemporary biology and physical chemistry. J Altern Complement Med. 2001;7:567–574. doi: 10.1089/10755530152639792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lad V. A Complete Guide to Clinical Assessment. Vol. 2. Albuquerque, NM: Ayurvedic Press; 2007. Textbook of Ayurveda. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lad V. Fundamental Principles. Vol. 1. Albuquerque, NM: Ayurvedic Press; 2001. Textbook of Ayurveda. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barret R. Lucas R. Hot and cold in transformation: Is Iban medicine humoral? Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:383–393. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hankey A. A test of the systems analysis underlying the scientific theory of Ayurveda's tridosha. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:385–390. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma H. Chandola HM. Singh G. Basisht G. Utilization of Ayurveda in health care: An approach for prevention, health promotion, and treatment of disease. Part I—Ayurveda, the science of life. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13:1011–1019. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.7017-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma H. Chandola HM. Singh G. Basisht G. Utilization of Ayurveda in health care: An approach for prevention, health promotion, and treatment of disease. Part 2—Ayurveda in primary health care. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13:1135–1150. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.7017-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zimmerman F. Rtu-Satmya: The seasonal cycle and the principle of appropriateness. Soc Sci Med. 1980;14B:99–106. doi: 10.1016/0160-7987(80)90058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nichter M. Coming to our senses: Appreciating the sensorial in medical anthropology. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2008;45:163–197. doi: 10.1177/1363461508089764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lock M. Ngyuen V-K. An Anthropology of Biomedicine. Chichester, UK and Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. Local biologies and human difference; pp. 83–110. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohnuki-Tierney E. Illness and Culture in Contemporary Japan: An Anthropological View. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richards G. Psychology: The Key Concepts. Boston, MA: Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson EO. Biophilia. Boston: Harvard University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayes L. Laurenceau JP. Feldman G. Change is not always linear: The study of non-linear and discontinuous patterns of change in psychotherapy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:715–723. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walach H. Jonas WB. Lewith GT. The role of outcomes research in evaluating complementary and alternative medicine. Altern Ther Health Med. 2002;8:88–95. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bodeker G. Evaluating Ayurveda. J Altern Complement Med. 2001;7:389–392. doi: 10.1089/10755530152639693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fønnebø V. Grimsgaard S. Walach H, et al. Researching complementary and alternative treatments: The gatekeepers are not at home. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hardy ML. Research in Ayurveda: Where do we go from here? Altern Ther Health Med. 2001;7:34–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rajani J. A biostatistical approach to Ayurveda: Quantifying the tridosha. J Complement Altern Med. 2004;10:879–889. doi: 10.1089/acm.2004.10.879. :2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hollenstein T. State space grids: Analyzing dynamics across development. Int J Behav Dev. 2007;31:384–396. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Howerter A. Hollenstein T. Boon H, et al. State–space grid analysis: Applications for clinical whole systems complementary and alternative medicine research. Forsch Komplementarmed. 2012;19(suppl 1):30–35. doi: 10.1159/000335187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deocaris CC. Widodo N. Wadhwa R. Kaul SC. Merger of Ayurveda and tissue culture–based functional genomics: Inspirations from systems biology. J Transl Med. 2008;6:14. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patwardhan B. Bodeker G. Ayurvedic genomics: Establishing a genetic basis for mind–body typologies. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14:571–576. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patwardhan B. Joshi K. Chopra A. Classification of human population based on HLA gene polymorphism and the concept of Prakriti in Ayurveda. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:349–353. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prasher B. Negi S. Aggarwal S. Whole genome expression and biochemical correlates of extreme constitutional types defined in Ayurveda. J Transl Med. 2008;6:48. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-6-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]