Abstract

Background

Many Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria produce large quantities of indole as an intercellular signal in microbial communities. Indole demonstrated to affect gene expression in Escherichia coli as an intra-species signaling molecule. In contrast to E. coli, Salmonella does not produce indole because it does not harbor tnaA, which encodes the enzyme responsible for tryptophan metabolism. Our previous study demonstrated that E. coli-conditioned medium and indole induce expression of the AcrAB multidrug efflux pump in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium for inter-species communication; however, the global effect of indole on genes in Salmonella remains unknown.

Results

To understand the complete picture of genes regulated by indole, we performed DNA microarray analysis of genes in the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain ATCC 14028s affected by indole. Predicted Salmonella phenotypes affected by indole based on the microarray data were also examined in this study. Indole induced expression of genes related to efflux-mediated multidrug resistance, including ramA and acrAB, and repressed those related to host cell invasion encoded in the Salmonella pathogenicity island 1, and flagella production. Reduction of invasive activity and motility of Salmonella by indole was also observed phenotypically.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that indole is an important signaling molecule for inter-species communication to control drug resistance and virulence of S. enterica.

Keywords: AcrAB, Indole, RamA, Salmonella, SPI-1

Background

Bacteria communicate using small molecules by a process termed quorum sensing. Accumulation of quorum-sensing signals in growth medium indicates cell density. The use of chemical signals for bacterial communication is a widespread phenomenon [1-5]. In Gram-negative bacteria, these signals could be N-acyl derivatives of homoserine lactone, cyclic dipeptides, and quinolones [6-12]. These signals regulate various functions such as bioluminescence, differentiation, virulence, DNA transfer, and biofilm maturation [13-22].

The intestinal tract is colonized by approximately 1012 commensal bacteria including those belonging to the genus Escherichia[23-25]. Among Enterobacteriaceae, indole is produced by E. coli and certain Proteeae such as Proteus vulgarisProvidencia spp., and Morganella spp. [26]. Indole production is commonly used for Escherichia coli identification [26]. Indole is generated from tryptophan by the enzyme tryptophanase, encoded by tnaA[27]. Extracellular indole is found at high concentrations (over 600 μM) when E. coli is grown in enriched medium [28]. Furthermore, indole has also been found in human feces at comparable concentrations (~250–1100 μM) [29,30]. Recent studies have also revealed that indole is an extracellular signal in E. coli, since it has been demonstrated to regulate uptake, synthesis, and degradation of amino acids in the stationary phase of planktonic cells [31], multicopy plasmid maintenance, cell division [32], biofilm formation [28], acid resistance [33], and expression of multidrug exporters in E. coli[34-36] as well as to regulate the pathogenicity island, including the locus of enterocyte effacement of pathogenic E. coli[37,38]. Indole has also been demonstrated as an important cell-signaling molecule for a population-based antibiotic resistance mechanism [39].

Salmonella enterica is a bacterial pathogen that causes various diseases in humans including gastroenteritis, bacteremia, and typhoid fever [40]. In contrast to E. coliS. enterica does not harbor tnaA; therefore, this organism does not produce indole [41]. In our previous study, we demonstrated that an E. coli-conditioned medium and indole induced expression of the acrABtolC multidrug efflux system of Salmonella in a RamA regulator-dependent manner [35]. This suggests that indole is used as a cell-signaling molecule in both intra- and inter-species communication. However, the global effect of indole on Salmonella remains to be elucidated.

We hypothesized that indole controls expression of a wide range of genes and plays a role in regulating the physiological functions of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium. Therefore, to reveal the complete picture of indole-controlled genes, we conducted microarray analysis of genes affected by indole. Predicted Salmonella phenotypes affected by indole based on the microarray data were also examined in this study.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains used in this study were the wild-type strain ATCC14028s [42] and its derivatives. These included strain NES114 which harbors a FLAG-tag fused at the chromosomal ramA gene (ramA-FLAG::KmR) and strain NES84 which carries a ramA reporter plasmid (ATCC 14028s/pNNramA) [35]. Derivatives also included various deletion mutants: ramA deletion mutant 14028s∆ramA::kanRramR deletion mutant 14028s∆ramR::kanR and mutant 14028s∆ram::kanR deleted of the whole ram locus. Bacterial strains were grown at 37 °C in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth supplemented with indole (Sigma) where appropriate.

DNA microarray analysis

The ATCC 14028s strain was grown in the presence or absence of 1 or 4 mM indole. The cells were rapidly collected for total RNA extraction when the culture reached an optical density (OD) of 0.6 at 600 nm. Total RNA was extracted from the cells using the RNeasy Midi kit (Qiagen) and Turbo DNA-free™ kit (Ambion). After extraction of total RNA, fluorescent labeling of cDNA was performed using the GeneChip DNA labeling reagents (Affimetrix). The fluorescent-labeled cDNA was hybridized in cDNA microarray plates (NimbleExpress™ S. typhimurium array; NimbleGen Systems, Inc.). The degree of fluorescence in the plates was measured and quantified using the GeneChip Scanner 3000 (Affymetrix) and GeneChip Operating Software ver. 1.4 (Affymetrix), respectively. Measured values were compared to control values, and p values of distribution of logged data were obtained. A ranked conversion of p values was calculated, and values lying inside 2.5 % of the two extremes were considered valid.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR

The ATCC 14028s strain was grown in the presence or absence of 2 mM indole. The cells were rapidly collected for total RNA extraction when the culture reached an OD600 of 0.6. Total RNA from bacterial cultures was extracted as described above. Semiquantitative RT-PCR was used to measure the transcriptional expression of rrs and ramA. RNA was reverse-transcribed using random hexamers and TaqMan reverse transcription reagents (Applied Biosystems), and PCR was performed using Takara LA Taq DNA polymerase (Takara Bio, Inc.). The primers for rrs were rrs-F and rrs-R (Table 1) and those for ramA were ramA-F and ramA-R (Table 1).

Table 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Oligonucleotide sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| For semiquantitative RT-PCR | |

|

rrs-F |

CCAGCAGCCGCGGTAAT |

|

rrs-R |

TTTACGCCCAGTAATTCCGATT |

|

ramA-F |

ATTTGAATCAGCCGTTACGTATTG |

|

ramA-R |

TGCAGGTGCCACTTGGAAT |

| For quantitative RT-PCR | |

|

gmk-f |

TTGGCAGGGAGGCGTTT |

|

gmk-r |

GCGCGAAGTGCCGTAGTAAT |

|

gyrB-f |

TCTCCTCACAGACCAAAGATAAGCT |

|

gyrB-r |

CGCTCAGCAGTTCGTTCATC |

|

rrs-f |

CCAGCAGCCGCGGTAAT |

|

rrs-r |

TTTACGCCCAGTAATTCCGATT |

|

ramA-f |

GCGTGAACGGAAGCTAAAAC |

|

ramA-r |

GGCCATGCTTTTCTTTACGA |

|

acrB-f |

TCGTGTTCCTGGTGATGTACCT |

|

acrB-r |

AACCGCAATAGTCGGAATCAA |

|

mdtE-f |

AGTCGCTGGATACCACCATC |

|

mdtE-r |

GATATTACGCACGCCGATTT |

|

tolC-f |

GCCCGTGCGCAATATGAT |

|

tolC-r |

CCGCGTTATCCAGGTTGTTG |

|

flhC-f |

ATATCCAGTTGGCGATGGAG |

|

flhC-r |

TTGCTCCCAGGTCATAAACC |

|

hilA-f |

CATGGCTGGTCAGTTGGAG |

|

hilA-r |

CGTAATTCATCGCCTAAACG |

|

invF-f |

TGAAAGCCGACACAATGAAAAT |

|

invF-r |

GCCTGCTCGCAAAAAAGC |

|

invA-f |

GGCGCCAAGAGAAAAAGATG |

|

invA-r |

CAAATATAACGCGCCATTGCT |

|

sipA-f |

TTTGGCTGTACGTTAGATCCGTTA |

| sipA-r | CCGCCGCTTTGTCAACA |

β-Galactosidase assay

The NES84 strain [35] was grown in the presence of 0–3 mM indole until an OD600 of 0.6 was reached. β-Galactosidase activity was determined as described by Miller [43]. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Construction of the ramA-FLAG strain

Insertion of the FLAG-tag of the ramA gene 3' terminal was performed as described by Datsenko and Wanner [44]. The kanamycin resistance gene aph, flanked by Flp recognition sites, was amplified by PCR using the primers ramA-FLAG-forward (GCCAGGCGCTTATCGTAAAGAAAAGCATGGCCGTACGCATGACTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAGTAGGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC) and ramA-FLAG-reverse (CGATTAAACATTTCAATGCGTACGGCCATGCTTTTCTTTACATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG). The sequence of the FLAG-tag appears in bold in the sequence of the ramA-FLAG-forward primer. The resulting PCR products were used to transform the recipient ATCC 14028s strain harboring the pKD46 plasmid, which expresses Red recombinase [44]. The chromosomal structure of the mutated loci was verified by PCR.

Western blotting

The NES114 strain (ramA-FLAG::KmR) was grown in the presence of 2 mM indole until an OD600 of 0.6 was reached. Bacterial cells were washed with buffer [20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 200 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA], resuspended in 1 ml of the same buffer, and disrupted by sonication using the Branson Sonifier 200 (Branson Sonic Power Co., Danbury, CT, USA) on ice for 2.5 min. Whole-cell lysate (10 μg of protein) was separated on 15 % SDS-PAGE using Tris-glycine SDS as the running buffer. The gel was transferred to PVDF membranes, and analyzed by western blotting using a monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma). The blot was developed using anti-mouse IgG horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody and analyzed using the ECL detection system (GE Healthcare).

Transmission electron microscopy

One hundred microliters of an overnight culture of the wild-type Salmonella strain was added to 5 ml of LB broth, and the bacterial culture was grown in the presence or absence of 1 mM indole until an OD600 of 0.6 was reached. Bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation, fixed in 2 % glutaraldehyde solution, and observed using a transmission electron microscope JEM-2100 (JEOL Ltd.).

Gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR

Bacteria were grown until mid-log phase (OD600 of 0.6) and harvested by centrifugation. Pelleted cultures were stabilized with RNAprotect Bacteria Reagent (Qiagen) and stored at −80 °C until use. Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini kit. (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Removal of residual genomic DNA was performed using the Turbo DNA-free kit (Ambion) and examined by negative PCR amplification of a chromosomal sequence. RNA integrity was examined by electrophoresis on 1 % agarose gel. Total RNA was reverse-transcribed using random hexamers and the Superscript III First Strand Synthesis System (Applied Biosystems). Primers used for qRT-PCR are listed in Table 1. The cycling conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 15 s. After each run, amplification specificity and the absence of primer dimers were examined using a dissociation curve acquired by heating the PCR products from 60 to 95 °C. The relative quantities of transcripts were determined using the standard curve method and normalized against the geometric mean of three reference genes (gmk, gyrB, rrs). In qRT-PCR experiments performed to address the effect of 1 mM indole, the expression level of each gene of interest was calculated as the average of three independent RNA samples. A two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to assess significance using a p value of <0.05 as a cutoff.

Measurement of motility of Salmonella

An overnight culture of the ATCC 14028s Salmonella strain was diluted in LB broth and grown in the presence or absence of 1 mM indole until an OD600 of 0.6 was reached. Next, 1 μl of bacterial culture was spotted in the center of a semi-solid agar plate containing 1 % tryptone peptone and 0.3 % BactoAgar and incubated at 37 °C for 3–5 h in a humidified incubator, after which strains were assessed for motility.

Invasion assay

Invasions assays were essentially performed as previously described [45]. Caco-2 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10 % inactivated fetal bovine serum, 1 % nonessential amino acids, and 1 % antibiotic solution (Gibco, Invitrogen). Cells harvested by trypsinization were seeded at 2 × 105 cells/well in a 24-well plate (Falcon) and incubated for 4 days at 37 °C under 5 % CO2 in the medium described above, to obtain a confluent monolayer. Antibiotic was removed 24 h before performing the invasion assays. Bacteria were grown to an OD600 of 0.6 in LB broth in the presence or absence of 1 mM indole. After washing with DMEM, bacteria were inoculated on Caco-2 cells at a multiplicity of infection of 30, and the plates were further incubated for 30 min. The bacteria-containing medium was removed from the wells, and the cells were washed with PBS. Cells were incubated for 1.5 h with DMEM supplemented with 100 μg/ml gentamicin. Cells were washed with PBS and lysed by the addition of sterile ultrapure water for 30 min. Serial dilutions were plated on LB agar. The percentage of penetrating bacteria was calculated on the basis of the ratio of the counted cfu to the bacterial inoculum. For each bacterial strain and for each condition, three replicates were used.

Results

Indole affects gene expression in Salmonella

The regulation of Salmonella genes in the wild-type strain ATCC 14028s by 1 or 4 mM indole, was analyzed using DNA microarray. To exclude noise data based on microarray analysis, we considered that genes for which expression changed in the presence of both 1 and 4 mM of indole were significantly regulated by indole. As a result, it was revealed that 24 (Table 2) and 53 genes (Table 3) were upregulated and downregulated by indole, respectively.

Table 2.

Salmonellagenes whose relative expression was increased by indole

| STM no. | Gene | Function | Effect of indole on gene expression (fold change) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration of indole (mM) | ||||

| 1 | 4 | |||

| STM0521 |

ybbV |

Putative cytoplasmic protein |

8.6 |

7.0 |

| STM0581 |

ramA |

Transcriptional regulator (activator) of acrAB and tolC (AraC/XylS family) |

7.0 |

39 |

| STM0584 |

entD |

Enterochelin synthetase, component D (phoshpantetheinyltransferase) |

6.1 |

7.5 |

| STM0707 |

kdpF |

Putative outer membrane protein |

8.6 |

18 |

| STM0823 |

ybiJ |

Putative periplasmic protein |

3.2 |

11 |

| STM1156 |

yceA |

Putative enzyme related to sulfurtransferases |

4.3 |

8.0 |

| STM1214 |

ycfR |

Putative outer membrane protein |

4.6 |

37 |

| STM1251 |

|

Putative molecular chaperone (small heat shock protein) |

11 |

9.2 |

| STM1355 |

ydiP |

Putative transcription regulator, AraC family |

11 |

7.5 |

| STM1472 |

|

Putative periplasmic protein |

7.5 |

15 |

| STM1790 |

hyaE |

Putative thiol-disulfide isomerase and thioredoxins |

7.0 |

9.2 |

| STM1868A |

|

Putative protein |

4.3 |

7.0 |

| STM2103 |

wcaJ |

Putative UDP-glucose lipid carrier transferase/glucose-1-phosphate transferase in colanic acid gene cluster |

4.0 |

5.3 |

| STM2106 |

wcaI |

Putative glycosyl transferase in colanic acid biosynthesis |

4.6 |

34 |

| STM2206 |

fruF |

Phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent sugar phosphotransferase system, EIIA 2 |

4.6 |

12 |

| STM3028 |

stdB |

Putative outer membrane usher protein |

6.5 |

6.5 |

| STM3444 |

bfd |

Regulatory or redox component complexing with Bfr, in iron storage and mobility |

8.0 |

20 |

| STM3511 |

yhgI |

Putative thioredoxin-like proteins and domain |

5.7 |

8.0 |

| STM3606 |

yhjB |

Putative transcriptional regulator (LuxR/UhpA familiy) |

7.0 |

20 |

| STM3668 |

yiaK |

Putative malate dehydrogenase |

7.0 |

9.2 |

| STM3941 |

|

Putative inner membrane protein |

8.6 |

18 |

| STM4213 |

|

Putative phage tail sheath protein |

6.5 |

5.7 |

| STM4327 |

fxsA |

Suppresses F exclusion of bacteriophage T7 |

4.9 |

5.7 |

| STM4548 | bglJ | Transcriptional regulator (activator) of bgl operon (LuxR/UhpA family) | 26 | 5.7 |

Table 3.

Salmonellagenes whose relative expression was decreased by indole

| STM no. | Gene | Function | Effect of indole on gene expression (fold change) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration of indole (mM) | ||||

| 1 | 4 | |||

| STM0701 |

speF |

Ornithine decarboxylase isozyme, inducible |

0.35 |

0.038 |

| STM0964 |

dmsA |

Anaerobic dimethyl sulfoxide reductase, subunit A |

0.12 |

0.063 |

| STM0965 |

dmsB |

Anaerobic dimethyl sulfoxide reductase, subunit B |

0.13 |

0.025 |

| STM1092 |

orfX |

Putative cytoplasmic protein |

0.082 |

0.031 |

| STM1171 |

flgN |

Flagellar biosynthesis: belived to be export chaperone for FlgK and FlgL |

0.27 |

0.082 |

| STM1183 |

flgK |

Flagellar biosynthesis, hook-filament junction protein 1 |

0.19 |

0.031 |

| STM1184 |

flgL |

Flagellar biosynthesis; hook-filament junction protein |

0.18 |

0.044 |

| STM1626 |

trg |

Methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein III, ribose and galactose sensor receptor |

0.15 |

0.054 |

| STM1732 |

ompW |

Outer membrane protein W; colicin S4 receptor; putative transporter |

0.29 |

0.047 |

| STM1764 |

narG |

Nitrate reductase 1, alpha subunit |

0.095 |

0.041 |

| STM1765 |

narK |

MFS superfamily, nitrite extrusion protein |

0.058 |

0.047 |

| STM1917 |

cheB |

Methyl esterase, response regulator for chemotaxis (cheA sensor) |

0.27 |

0.067 |

| STM1918 |

cheR |

Glutamate methyltransferase, response regulator for chemotaxis |

0.14 |

0.0078 |

| STM1919 |

cheM |

Methyl accepting chemotaxis protein II, aspartate sensor-receptor |

0.18 |

0.018 |

| STM1921 |

cheA |

Sensory histitine protein kinase, transduces signal between chemo- signal receptors and CheB and CheY |

0.18 |

0.029 |

| STM1922 |

motB |

Enables flagellar motor rotation, linking torque machinery to cell wall |

0.15 |

0.021 |

| STM1923 |

motA |

Proton conductor component of motor, torque generator |

0.20 |

0.036 |

| STM1960 |

fliD |

Flagellar biosynthesis; filament capping protein; enables filament assembly |

0.31 |

0.011 |

| STM1961 |

fliS |

Flagellar biosynthesis; repressor of class 3a and 3b operons (RflA activity) |

0.31 |

0.019 |

| STM1962 |

fliT |

Flagellar biosynthesis; possible export chaperone for FliD |

0.25 |

0.038 |

| STM2256 |

napB |

Periplasmic nitrate reductase, small subunit, cytochrome C550, in complex with NapA |

0.23 |

0.082 |

| STM2257 |

napH |

Ferredoxin-type protein: electron transfer |

0.12 |

0.067 |

| STM2258 |

napG |

Ferredoxin-type protein: electron transfer |

0.077 |

0.027 |

| STM2259 |

napA |

Periplasmic nitrate reductase, large subunit, in complex with NapB |

0.072 |

0.033 |

| STM2260 |

napD |

Periplasmic nitrate reductase |

0.063 |

0.0078 |

| STM2261 |

napF |

Ferredoxin-type protein: electron transfer |

0.044 |

0.024 |

| STM2872 |

prgJ |

Cell invasion protein; cytoplasmic |

0.22 |

0.10 |

| STM2873 |

prgI |

Cell invasion protein; cytoplasmic |

0.18 |

0.041 |

| STM2874 |

prgH |

Cell invasion protein |

0.082 |

0.0078 |

| STM2885 |

sipB |

Cell invasion protein |

0.33 |

0.11 |

| STM2897 |

invE |

Invasion protein |

0.25 |

0.038 |

| STM2899 |

invF |

Invasion protein |

0.12 |

0.095 |

| STM3127 |

|

Putative cytoplasmic protein |

0.29 |

0.058 |

| STM3128 |

|

Putative oxidoreductase |

0.14 |

0.036 |

| STM3129 |

|

Putative NAD-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenase |

0.14 |

0.047 |

| STM3149 |

hybA |

Function unknown, intitally thought to be hydrogenase-2 small subunit which now identified as hybO |

0.25 |

0.025 |

| STM3216 |

|

Putative methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein |

0.16 |

0.038 |

| STM3217 |

aer |

Aerotaxis sensor receptor, senses cellular redox state or proton motive force |

0.13 |

0.047 |

| STM3242 |

tdcD |

Propionate kinase/acetate kinase II, anaerobic |

0.14 |

0.029 |

| STM3243 |

tdcC |

HAAAP family, L-threonine/L-serine permease, anaerobically inducible |

0.082 |

0.044 |

| STM3244 |

tdcB |

Threonine dehydratase, catabolic |

0.063 |

0.029 |

| STM3245 |

tdcA |

Transcriptional activator of tdc operon (LysR family) |

0.18 |

0.095 |

| STM3577 |

tcp |

Methyl-accepting transmembrane citrate/phenol chemoreceptor |

0.13 |

0.041 |

| STM3626 |

dppF |

ABC superfamily (atp_bind), dipeptide transport protein |

0.31 |

0.036 |

| STM3628 |

dppC |

ABC superfamily (membrane), dipeptide transport protein 2 |

0.33 |

0.088 |

| STM4258 |

|

Putative methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein |

0.08 |

0.088 |

| STM4300 |

fumB |

Fumarase B (fumarate hydratase class I), anaerobic isozyme |

0.19 |

0.088 |

| STM4305 |

|

Putative anaerobic dimethyl sulfoxide reductase, subunit A |

0.14 |

0.082 |

| STM4306 |

|

Putative anaerobic dimethyl sulfoxide reductase, subunit B |

0.11 |

0.058 |

| STM4452 |

nrdD |

Anaerobic ribonucleoside-triphosphate reductase |

0.047 |

0.095 |

| STM4465 |

|

Putative ornithine carbamoyltransferase |

0.19 |

0.10 |

| STM4466 |

|

Putative carbamate kinase |

0.19 |

0.10 |

| STM4467 | Putative arginine deiminase | 0.082 | 0.019 | |

Genes upregulated by indole

Expression of the 24 genes listed in Table 2 was upregulated by both 1 and 4 mM indole. Eighteen genes are considered to code for putative proteins, and four genes, ramAydiPyhjB, and bglJ, are regulatory in nature. The transcriptional activator RamA, which belongs to the AraC/XylS family of regulatory proteins, promotes multidrug resistance by increasing expression of the AcrAB–TolC multidrug efflux system in several pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae[35,46-53]. RamA has also been reported to negatively affect virulence [47]. Both YdiP and YhjB are putative transcription regulators that belong to the AraC and LuxR/UhpA families, respectively (Table 2). YhjB is considered a response regulator comprising a CheY-like receiver domain and a helix-turn-helix DNA-binding domain. YhjB in E. coli stimulates dephosphorylation of two histidine kinases, EnvZ and NtrB, although the sensor kinase for YhjB phosphorylation has not yet been identified [54]. BglJ forms a heterodimer with RcsB to relieve repression of the E. coli bgl operon and allow arbutin and salicin transport and utilization [55,56]. Expression of all these regulatory genes increased by more than 10-fold in the presence of indole. Of particular interest, expression of ramA increased by 39-fold in response to 4 mM indole. Noticeably, higher indole concentration did not always lead to a higher expression level. Indeed, bglJ expression was more increased in response to 1 mM indole (26-fold) than to 4 mM indole (5.7-fold).

Among other genes upregulated by indole, functions of the gene products of entDfruFbfd, and fxsA have been characterized. EntD has phosphopantetheinyl transferase activity [57] and is involved in biosynthesis of the iron-acquiring siderophore enterobactin [58]. FruF is a bifunctional PTS system fructose-specific transporter subunit IIA/HPr protein [41,59]. Bfd is a bacterioferritin-associated ferredoxin considered to be involved in Bfr iron storage and release functions or in regulation of Bfr [41]. FxsA of E. coli was described as a suppressor of the F exclusion of phage T7 [60]. Expression of all these genes was more strongly induced by 4 mM indole than by 1 mM indole.

Genes downregulated by indole

Microarray analysis revealed that fifty-three genes were repressed by both 1 and 4 mM indole (Table 3). Expression of all these genes excluding STM4258 and nrdD was reduced by 4 mM indole compared to that by 1 mM indole. Although there are 10 putative genes, functions of most gene products have been characterized (Table 3).

Microarray analysis revealed that indole represses expression of genes related to bacterial motility including flagella biosynthesis (flgN/K/L and fliD/S/T), chemotaxis (cheB/R/M/Aaer[61], tcp, and trg), and flagella motor activity (motB/A). Indole also decreased expression of genes related to cell invasion such as prgJ/I/HsipB, and invE/F, which are encoded by the Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1). Expression of genes related to anaerobic respiration was decreased by indole. The genes repressed by indole included narG (nitrate reductase), narK (nitrate-nitrite antiporter), and genes in the nap operon encoding nitrate reductase (Nap) such as napB/H/G/A/D/F[62]. The tdc operon including tdcA/B/C/D, which are responsible for the anaerobic degradation of threonine [63], was also downregulated by indole. In addition to these genes, other genes related to anaerobic respiration such as dmsA/B (anaerobic dimethyl sulfoxide reductase), fumB (fumarase B, anaerobic isozyme), nrdD (anaerobic ribonucleoside-triphosphate reductase), and STM4305/4306 (putative anaerobic dimethyl sulfoxide reductase, subunit A/B) were also repressed by indole. Indole also repressed membrane protein genes such as ompW (outer membrane protein involved in osmoregulation that is also affected by environmental conditions) and dppF/C (dipeptide transport protein).

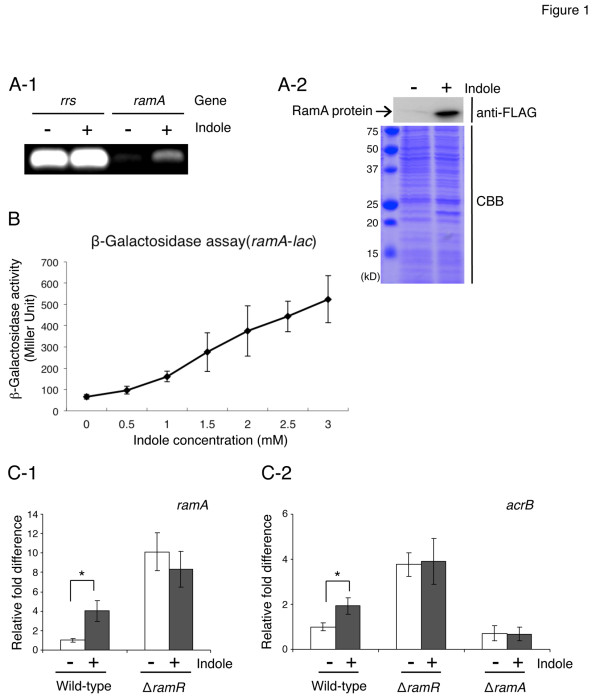

Indole upregulates genes involved in efflux-mediated multidrug resistance

As reported above, microarray analysis identified that indole significantly increased expression of ramA, encoding a transcriptional activator of the multidrug transporter genes acrAB and tolC of Salmonella[35]. To confirm this result, we performed reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and observed that transcript levels of ramA increased when bacterial cells of the strain ATCC 14028s were treated with 2 mM indole (Figure 1A-1). To investigate whether indole induces production of RamA, we constructed a strain NES114 that harbors a FLAG-tag fused to chromosomally-encoded ramA. Western blotting revealed increased production of RamA in the presence of 2 mM indole (Figure 1A-2). Microarray analysis demonstrated that expression of ramA was more strongly induced by 4 mM indole (39-fold increase relative to untreated cells) than by 1 mM indole (7.0-fold increase), indicating that the effect of indole on expression of ramA may be concentration dependent. To investigate the effect of different indole concentrations on the promoter activity of ramA, a β-galactosidase assay with the NES84 strain [35] was performed, and it was found that indole activated the ramA promoter in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1B). The finding of enhanced promoter activity of ramA is in good agreement with our previous observation [35].

Figure 1.

Indole induces efflux-mediated multidrug resistance genes. (A-1) RT-PCR measurement of indole effect on expression of ramA. Expression of rrs, encoding rRNA, was measured as a control. The wild-type strain ATCC14028s was grown in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 2 mM indole, and RT-PCR was performed after RNA isolation. (A-2) RamA production in the wild-type ATCC14028s derivative strain carrying the epitope-tagged ramA. NES114 (ramA-FLAG::KmR) was grown in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 2 mM indole. SDS-PAGE of lysates of NES114 was followed by Western blotting with an anti-FLAG antibody (anti-FLAG, top) or by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB, bottom). (B) β-Galactosidase levels in the wild-type ATCC 14028s derivative strain carrying the ramA-lac transcriptional fusion (NES84) treated with different indole concentrations. (C-1) qRT-PCR measurement of indole effect on expression of ramA. The wild-type strain (ATCC14028s) and its ramR::kanR deletion mutant were grown in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 1 mM indole. (C-2) qRT-PCR measurement of indole effect on expression of acrB. The wild-type strain ATCC14028s and its ramR::kanR and ramA::kanR deletion mutants were grown in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 1 mM indole. (B and C-1, 2) The data correspond to mean values from three independent replicates. The bars indicate the standard deviation. (C-1, 2) ramA and acrB expression levels were expressed relative to that measured in the wild-type strain grown without indole, which was assigned the unit value. Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) according to a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Confirming classical RT-PCR results, quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) indicated that expression of ramA in the strain ATCC 14028s increases by 4-fold in the presence of 1 mM indole (Figure 1C-1). As previously reported, RamR represses to the same extent the expression of ramA[46,64]. Therefore, to determine a possible contribution of RamR to induction of expression of ramA via indole, the effect of 1 mM indole on expression of ramA in a ∆ramR strain (14028s∆ramR::kanR) was examined. At this concentration indole did not induce expression of ramA suggesting indole-mediated ramA induction is indeed dependent on the presence of RamR (Figure 1C-1). However, whereas indole was shown to induce expression of acrB in the wild-type strain, this induction was neither observed in the ∆ramR (14028s∆ramR::kanR) nor in the ∆ramA strain (14028s∆ramA::kanR) (Figure 1C-2). This suggested that indole-mediated induction of acrB expression is not solely dependent on RamA, but nevertheless also requires the presence of the RamR transcriptional repressor.

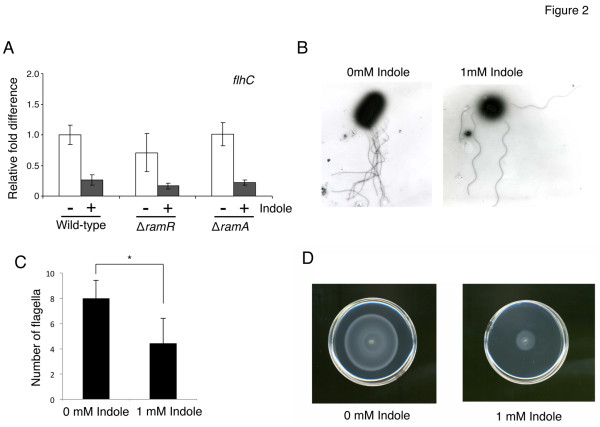

Indole represses motility of Salmonella

Expression of genes related to bacterial flagella biosynthesis, flagella motor activity, and chemotaxis was repressed by indole, and this repression was predicted to have profound negative effects on flagellar synthesis and bacterial motility. FlhC is a master regulator protein involved in flagellar biogenesis in Salmonella[65]. Indole also reduced expression of flhC, and this reduction was independent of ramA and ramR (Figure 2A). To confirm the microarray findings, we examined the effect of indole on the presence of flagella in wild-type Salmonella cells by transmission electron microscopy (Figure 2B). Flagella were detectable in bacterial cells regardless of indole treatment; however, the number of flagella decreased when cells were treated with indole (Figure 2B and C). It was observed that motility of Salmonella ATCC 14028s strain decreased in the semi-solid agar plate when bacterial cells were treated with indole (Figure 2D). These results suggest that the reduction in the number of flagella by indole may affect motility of Salmonella.

Figure 2.

Indole represses flagella production and motility ofSalmonella. (A) The effect of indole on expression of flhC measured by qRT-PCR. The wild-type strain ATCC 14028s and its ramR::kanR and ramA::kanR deletion mutants were grown in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 1 mM indole. flhC expression level was expressed relative to that measured in the wild-type strain grown without indole, which was assigned the unit value. The data corresponds to mean values from three independent replicates. The bars indicate the standard deviation. (B) Transmission electron microscopy was used to detect flagella on the wild-type strain (ATCC 14028s) grown in the presence or absence of 1 mM indole. (C) The number of flagella attached to a single cell was counted from images taken using transmission electron microscopy. Data were collected from 30 bacterial cells for both indole-treated and untreated cells. Bars correspond to the standard deviation. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.01) according to the two-tailed Student’s t-test. (D) Indole represses motility of Salmonella. After incubation of the wild-type ATCC 14028s strain in the presence or absence of 1 mM indole, motility was assayed on a semi-solid agar plate. Result is representative of one of the three experiments.

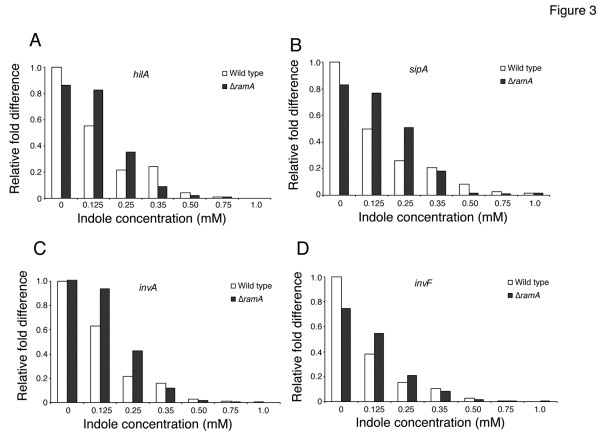

Indole represses expression of the invasion genes

Inside the host, S. enterica serovars can invade and survive in epithelial cells and macrophages. Therefore, invasion of the host intestinal cells is critical for initiation of salmonellosis. Several genetic elements responsible for the invasive phenotype of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium are located in SPI-1, a 40-kbp region of the chromosome at centrisome 63. As described above, we found that genes located in SPI-1 such as prgJ/I/HsipB, and invE/F were repressed by indole. To further investigate repression of SPI-1 genes by indole, we measured expression of hilAsipAinvA, and invF of the ATCC 14028s strain in response to different indole concentration by qRT-PCR (Figure 3). hilA is located on SPI-1, and it encodes the HilA regulator, which controls expression of SPI-1 genes, including the type III secretion system (T3SS). invF also encodes an invasion regulatory protein of SPI-1. sipA encodes an effector protein, the secretion of which is mediated by T3SS. invA encodes a structural component of T3SS. qRT-PCR revealed that indole decreased expression of hilAsipAinvA, and invF in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 3). Since it was reported that overexpression of ramA results in decreased expression of SPI-1 genes [47] and our study indicated that indole induces ramA, we investigated the effect of ramA deletion on expression of SPI-1 genes regulated by indole. As shown in Figure 3, indole repressed expression of hilAsipAinvA, and invF; however, its repressive effect on those in the ramA-deleted mutant (14028s∆ramA::kanR) was slightly lower than that observed in the wild-type strain (ATCC 14028s) when bacterial cells were treated with 0.125 or 0.25 mM indole. In contrast, when bacterial cells were treated with concentrations of indole of 0.35 mM or more, the repressive effect on SPI-1 genes was similar in the wild-type and in the mutant strains. These data suggest that indole partially represses SPI-1 genes in a RamA-dependent manner when cells are treated with lower indole concentrations; however, the repressive effect of indole on SPI-1 may be RamA-independent at higher concentrations.

Figure 3.

Indole represses expression of invasion genes encoded by SPI-1. The effect of indole on expression of SPI-1 genes including hilA (A), sipA (B), invA (C), and invF (D) was measured by qRT-PCR. The wild-type ATCC 14028s strain (open bars) and its ramA::kanR deletion mutant (solid bars) were grown with indole concentrations between 0 and 1 mM. Genes expression levels were expressed relative to that measured in the wild-type strain grown without indole, which was assigned the unit value.

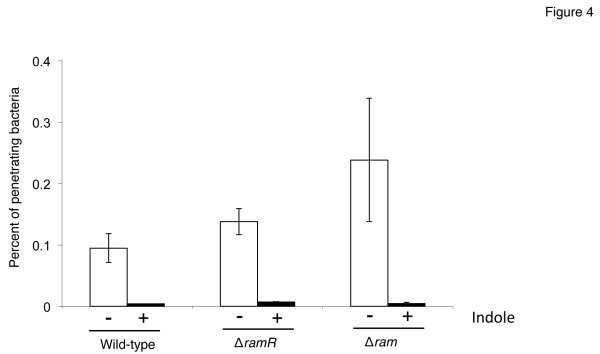

A critical step in Salmonella pathogenesis is invasion of enterocytes and M cells of the small intestine via expression of a type III secretion system encoded by SPI-1 that secretes effector proteins into host cells, leading to engulfment of bacteria within large membrane ruffles. As indicated previously, indole represses expression of genes encoded by SPI-1, suggesting that indole reduces invasion of mammalian cells by Salmonella. To examine this possibility, we investigated the effect of indole in an invasion assay using Caco-2 cells. When bacterial cells were treated with 1 mM indole, the invasion rate of Salmonella was reduced compared to that in untreated bacterial cells (Figure 4). We also examined the effect of deletions of ramR and of the whole ram locus on invasive activity of Salmonella treated with 1 mM indole. Indole repressed invasive activity of the ∆ramR (14028s∆ramR::kanR) and of the ∆ram mutant (14028s∆ram::kanR), as observed with the wild-type strain (Figure 4). These data suggest that 1 mM indole phenotypically represses invasive activity of Salmonella in a ram locus-independent manner.

Figure 4.

Indole reduces invasive activity ofSalmonellacells. In vitro invasion of Caco-2 cells by the wild-type ATCC 14028s strain and its ramR::kanR and ram::kanR deletion mutants grown in the presence (+, solid bars) or absence (−, open bars) of 1 mM indole. The percentage of intracellular bacteria was determined after infecting Caco-2 human intestinal epithelial cells and gentamicin treatment. Results are representative of a single experiment where each strain was tested in triplicates.

Discussion

Increasing evidence indicates that indole controls various phenotypes of E. coli including multidrug resistance and virulence as an extracellular signal [28,31-34,37-39]. In contrast to E. coli, the effect of indole on Salmonella had not been clearly elucidated, probably because Salmonella does not produce indole. Therefore, we sought to resolve the effect of indole on gene expression in the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium ATCC 14028s strain by microarray analysis. As hypothesized and confirmed in previous studies [35,36], microarray analysis revealed that indole increased expression of ramA, which is involved in regulation of the AcrAB–TolC multidrug efflux system.

Including ramA, 24 genes were upregulated by indole. Among them, 18 were more strongly induced by 4 mM indole than by 1 mM indole. Conversely, 53 genes were downregulated by indole, 51 of which were more strongly repressed by 4 mM indole than by 1 mM indole. These data suggested that expression of most indole-regulated genes is indole concentration dependent. In fact, promoter activity of ramA increased as indole concentration increased. Similarly, expression of SPI-1 genes decreased as indole concentration increased.

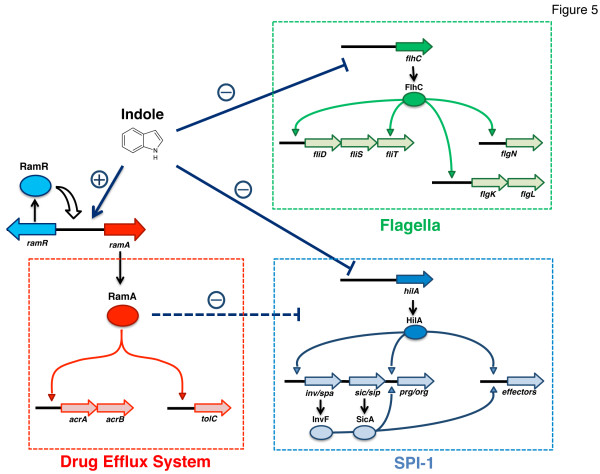

Indole induced ramA, and this induction is probably responsible for induction of acrB, which encodes the multidrug efflux pump (Figure 5). Most of the genes upregulated by indole encode putative proteins. Several of the genes, such as STM1251, STM1472, STM1868A, STM3941, and STM4213, have yet to be named. Among these, the only gene identified in E. coli is STM4213, which encodes a putative phage tail sheath protein. If the function of these putative genes is clarified, then other phenotypes induced by indole in addition to multidrug resistance will also be understood.

Figure 5.

Proposed regulatory network controlled by indole. Indole induces the multidrug efflux system genes acrAB and tolC through the increased expression of ramA. Indole represses flagellar and SPI-1 genes in a ram locus-independent manner. However, the indole-mediated upregulation of ramA may be partially involved in decreased expression of SPI-1 genes.

In this study, we found that indole repressed various genes related to bacterial motility and virulence. Decreased motility and invasive activity of Salmonella were also phenotypically observed. Recent studies revealed the coordinate regulation of flagellar and SPI-1 genes by FliZ, encoded by a gene in the fliA operon [66,67]. It was demonstrated that FliZ posttranslationally controls HilD to positively regulate expression of hilA[67]. Our microarray data revealed reduced expression of fliZ when bacterial cells were treated with indole (fliZ expression was reduced to 0.47- and 0.038-fold of the level in untreated cells by 1 and 4 mM indole, respectively), and that expression of hilA was also repressed by indole. Indole may coordinately repress flagellar and SPI-1 genes via the regulatory network of FliZ. Because previous study indicated that both RamA and RamR are involved in the control of SPI-1 genes [47], we examined their effects on repression of SPI-1 genes and invasive activity of Salmonella. The results suggested that indole sup presses SPI-1 genes in a RamA/RamR-independent manner (Figure 5). Similarly, repression of flhC by indole was also RamA/RamR independent. These data are suggestive of the presence of another pathway for indole to repress flagellar and SPI-1 genes, whereas acrAB/tolC is induced by indole in a RamR/RamA-dependent manner. Bacterial adhesion to the Caco-2 cells, which is the primary step of the cell invasion process, was not addressed in our experiments. However, since flagella were repressed by indole, it cannot be excluded that the defective invasion partially resulted from a lesser adhesion to the cells, and not only to the repression of SPI-1 genes. It should also be noted that several of the indole-repressed genes are related to anaerobic respiration in addition to motility and SPI-1 genes. Because it is suggested that indole is a biological oxidant in bacteria [68], this oxidative effect may lead to repression of these genes.

In conclusion, we identified that indole induces expression of genes related to efflux-mediated multidrug resistance and represses expression of genes related to invasive activity and motility of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium. Reduction of invasive activity and motility of Salmonella by indole was phenotypically observed. Because Salmonella itself does not produce indole, our results suggest that indole could also be an important signaling molecule for inter-species communication to control drug resistance and virulence of Salmonella in addition to its role in intra-species communication in E. coli. Indeed, it was previously demonstrated that E. coli-conditioned medium induced the AcrAB pump in Salmonella through the RamA regulator [35]. The type of environment in which Salmonella experiences the effect of indole is not well understood. It is believed that Salmonella may be exposed to high indole concentrations in the intestine, in which several species of indole-producing bacteria exist. In fact, indole is found in human feces at comparable concentrations (~250–1100 μM) [29,30], and recent studies indicated the importance of indole in favorable inter-kingdom signaling interactions between the intestinal epithelial cells and commensal bacteria [69]. In addition to indole itself, indole derivatives such as skatole (3-methylindole) also occur naturally in feces after being produced from tryptophan in the mammalian digestive tract. Therefore, indole and skatole may additively affect gene expression in Salmonella. In fact, when we examined the effect of skatole by a β-galactosidase assay, it significantly stimulated the promoter activity of ramA (unpublished data). Thus, there is a possibility that these molecules enhance drug resistance of Salmonella, while simultaneously repressing their motility and pathogenicity in the intestinal tract. Interestingly, the effect of indole on the pathogenicity of E. coli is the opposite of that on Salmonella. In enterohemorrhagic E. coli, it was suggested that indole can activate expression of EspA and EspB as well as secretion and stimulate the ability of EHEC to form attaching and effacing lesions in human cells [38]. Thus, although indole secreted by E. coli enhances the virulence of E. coli, it reduces the virulence of Salmonella, probably to the advantage of E. coli. This finding suggests that the gastrointestinal flora may affect regulation of virulence traits in Salmonella via the signaling of indole.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: EN, EG, SB, AC, KN. Performed the experiments: EN, EG, SB, SY, AW. Analyzed the data: EN, EG, SB, SY, AW, KO, TT, AY, AC, KN. Wrote the paper: EG, AC, KN. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan; a grant from the Mishimakaiun Memorial Foundation; the Program for Promotion of Fundamental Studies in Health Sciences of the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation; and the Funding Program for Next Generation World-Leading Researchers. It was also partly supported by the French Région Centre (grant 2008 00036085) and partly by the European Union with the European Regional Development Fund (grant 1634–32245). The funders had no role in this study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Eiji Nikaido, Email: eiji.nikaido@shionogi.co.jp.

Etienne Giraud, Email: etienne.giraud@tours.inra.fr.

Sylvie Baucheron, Email: sylvie.baucheron@tours.inra.fr.

Suguru Yamasaki, Email: suguru37@sanken.osaka-u.ac.jp.

Agnès Wiedemann, Email: awiedemann@tours.inra.fr.

Kousuke Okamoto, Email: okamotok@phs.osaka-u.ac.jp.

Tatsuya Takagi, Email: satan@gen-info.osaka-u.ac.jp.

Akihito Yamaguchi, Email: akihito@sanken.osaka-u.ac.jp.

Axel Cloeckaert, Email: Axel.Cloeckaert@tours.inra.fr.

Kunihiko Nishino, Email: nishino@sanken.osaka-u.ac.jp.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mitsuko Hayashi-Nishino for the protocol for the invasion assay and excellent advice and Ikue Shirosaka, Coralie Porte-Lebiguais, Isabelle Monchaux and Imane Boumart for excellent technical assistance.

References

- Fuqua C, Winans SC, Greenberg EP. Census and consensus in bacterial ecosystems: the LuxR-LuxI family of quorum-sensing transcriptional regulators. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:727–751. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua WC, Winans SC, Greenberg EP. Quorum sensing in bacteria: the LuxR-LuxI family of cell density-responsive transcriptional regulators. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:269–275. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.2.269-275.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser D, Losick R. How and why bacteria talk to each other. Cell. 1993;73:873–885. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90268-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleerebezem M, Quadri LE, Kuipers OP, de Vos WM. Quorum sensing by peptide pheromones and two-component signal-transduction systems in Gram-positive bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:895–904. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4251782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmond GP, Bycroft BW, Stewart GS, Williams P. The bacterial 'enigma': cracking the code of cell-cell communication. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:615–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao JG, Meighen EA. Purification and structural identification of an autoinducer for the luminescence system of Vibrio harveyi. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:21670–21676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard A, Burlingame AL, Eberhard C, Kenyon GL, Nealson KH, Oppenheimer NJ. Structural identification of autoinducer of Photobacterium fischeri luciferase. Biochemistry. 1981;20:2444–2449. doi: 10.1021/bi00512a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden MT, Ram Chhabra S, de Nys R, Stead P, Bainton NJ, Hill PJ, Manefield M, Kumar N, Labatte M, England D. et al. Quorum-sensing cross talk: isolation and chemical characterization of cyclic dipeptides from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other gram-negative bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:1254–1266. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson JP, Gray KM, Passador L, Tucker KD, Eberhard A, Iglewski BH, Greenberg EP. Structure of the autoinducer required for expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:197–201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesci EC, Milbank JB, Pearson JP, McKnight S, Kende AS, Greenberg EP, Iglewski BH. Quinolone signaling in the cell-to-cell communication system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11229–11234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesci EC. New signal molecules on the quorum-sensing block: response. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:103–104. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01717-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Murphy PJ, Kerr A, Tate ME. Agrobacterium conjugation and gene regulation by N-acyl-L-homoserine lactones. Nature. 1993;362:446–448. doi: 10.1038/362446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baca-DeLancey RR, South MM, Ding X, Rather PN. Escherichia coli genes regulated by cell-to-cell signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4610–4614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassler BL, Wright M, Showalter RE, Silverman MR. Intercellular signalling in Vibrio harveyi: sequence and function of genes regulating expression of luminescence. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:773–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Q, Campbell EA, Naughton AM, Johnson S, Masure HR. The com locus controls genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:683–692. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2481617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies DG, Parsek MR, Pearson JP, Iglewski BH, Costerton JW, Greenberg EP. The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science. 1998;280:295–298. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engebrecht J, Nealson K, Silverman M. Bacterial bioluminescence: isolation and genetic analysis of functions from Vibrio fischeri. Cell. 1983;32:773–781. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Yu B, Bainton NJ, Birdsall M, Bycroft BW, Chhabra SR, Cox AJ, Golby P, Reeves PJ, Stephens S. et al. The lux autoinducer regulates the production of exoenzyme virulence determinants in Erwinia carotovora and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. EMBO J. 1993;12:2477–2482. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05902.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latifi A, Winson MK, Foglino M, Bycroft BW, Stewart GS, Lazdunski A, Williams P. Multiple homologues of LuxR and LuxI control expression of virulence determinants and secondary metabolites through quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:333–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17020333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passador L, Cook JM, Gambello MJ, Rust L, Iglewski BH. Expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes requires cell-to-cell communication. Science. 1993;260:1127–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.8493556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper KR, Beck von Bodman S, Farrand SK. Conjugation factor of Agrobacterium tumefaciens regulates Ti plasmid transfer by autoinduction. Nature. 1993;362:448–450. doi: 10.1038/362448a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirhonen M, Flego D, Heikinheimo R, Palva ET. A small diffusible signal molecule is responsible for the global control of virulence and exoenzyme production in the plant pathogen Erwinia carotovora. EMBO J. 1993;12:2467–2476. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05901.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke MB, Sperandio V. Events at the host-microbial interface of the gastrointestinal tract III. Cell-to-cell signaling among microbial flora, host, and pathogens: there is a whole lot of talking going on. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:1105–1109. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00572.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier-Hyams LS, Neish AS. Innate immune relationship between commensal flora and the mammalian intestinal epithelium. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:1339–1348. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5038-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BT, Lyte M, Chen C, Xie Y, Casey MA, Kulkarni-Narla A, Vulchanova L, Brown DR. Adrenergic modulation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 adherence to the colonic mucosa. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G1238–1246. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00471.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenwirth AC. In: Microbiology. 3. Davis BD, Dulbecco R, Eisen HN, Ginsberg HS, editor. Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc, Philadelphia, Pa; 1980. The enteric bacteria and bacteroides; pp. 645–672. [Google Scholar]

- Yanofsky C, Horn V, Gollnick P. Physiological studies of tryptophan transport and tryptophanase operon induction in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6009–6017. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.19.6009-6017.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domka J, Lee J, Wood TK. YliH (BssR) and YceP (BssS) regulate Escherichia coli K-12 biofilm formation by influencing cell signaling. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:2449–2459. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2449-2459.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin DA, Mastromarino AJ, Jones RD, Stroehlein JR, Lorentz O. Fecal skatole and indole and breath methane and hydrogen in patients with large bowel polyps or cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1985;109:135–141. doi: 10.1007/BF00391888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccato E, Venturi M, Di Leo G, Colombo L, Bertolo C, Doldi SB, Mussini E. Role of bile acids and metabolic activity of colonic bacteria in increased risk of colon cancer after cholecystectomy. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:514–519. doi: 10.1007/BF01316508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Ding X, Rather PN. Indole can act as an extracellular signal in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:4210–4216. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.14.4210-4216.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chant EL, Summers DK. Indole signalling contributes to the stable maintenance of Escherichia coli multicopy plasmids. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:35–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa H, Hayashi-Nishino M, Yamaguchi A, Nishino K. Indole enhances acid resistance in Escherichia coli. Microb Pathog. 2010;49:90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa H, Inazumi Y, Masaki T, Hirata T, Yamaguchi A. Indole induces the expression of multidrug exporter genes in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:1113–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido E, Yamaguchi A, Nishino K. AcrAB multidrug efflux pump regulation in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium by RamA in response to environmental signals. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:24245–24253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804544200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido E, Shirosaka I, Yamaguchi A, Nishino K. Regulation of the AcrAB multidrug efflux pump in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in response to indole and paraquat. Microbiology. 2011;157:648–655. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.045757-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anyanful A, Dolan-Livengood JM, Lewis T, Sheth S, Dezalia MN, Sherman MA, Kalman LV, Benian GM, Kalman D. Paralysis and killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli requires the bacterial tryptophanase gene. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:988–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa H, Kodama T, Takumi-Kobayashi A, Honda T, Yamaguchi A. Secreted indole serves as a signal for expression of type III secretion system translocators in enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Microbiology. 2009;155:541–550. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.020420-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HH, Molla MN, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Bacterial charity work leads to population-wide resistance. Nature. 2010;467:82–85. doi: 10.1038/nature09354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer CAaM SI. Principles of Bacterial Pathogenesis. Academic Press, New York. 2001; :266–333. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland M, Sanderson KE, Spieth J, Clifton SW, Latreille P, Courtney L, Porwollik S, Ali J, Dante M, Du F. et al. Complete genome sequence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. Nature. 2001;413:852–856. doi: 10.1038/35101614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields PI, Swanson RV, Haidaris CG, Heffron F. Mutants of Salmonella typhimurium that cannot survive within the macrophage are avirulent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5189–5193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JH. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. 1972; :352–355. [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosselin M, Virlogeux-Payant I, Roy C, Bottreau E, Sizaret PY, Mijouin L, Germon P, Caron E, Velge P, Wiedemann A. Rck of Salmonella enterica, subspecies enterica serovar enteritidis, mediates zipper-like internalization. Cell Res. 2010;20:647–664. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abouzeed YM, Baucheron S, Cloeckaert A. ramR mutations involved in efflux-mediated multidrug resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2428–2434. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00084-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey AM, Ivens A, Kingsley R, Cottell JL, Wain J, Piddock LJ. RamA, a member of the AraC/XylS family, influences both virulence and efflux in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:1607–1616. doi: 10.1128/JB.01517-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chollet R, Chevalier J, Bollet C, Pages JM, Davin-Regli A. RamA is an alternate activator of the multidrug resistance cascade in Enterobacter aerogenes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:2518–2523. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2518-2523.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney D, Ruzin A, Bradford PA. RamA, a transcriptional regulator, and AcrAB, an RND-type efflux pump, are associated with decreased susceptibility to tigecycline in Enterobacter cloacae. Microb Drug Resist. 2007;13:1–6. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2006.9990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XZ, Nikaido H. Efflux-mediated drug resistance in bacteria: an update. Drugs. 2009;69:1555–1623. doi: 10.2165/11317030-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzin A, Immermann FW, Bradford PA. Real-time PCR and statistical analyses of acrAB and ramA expression in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3430–3432. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00591-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Cui S, Meng J. Effect of transcriptional activators RamA and SoxS on expression of multidrug efflux pumps AcrAB and AcrEF in fluoroquinolone-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:95–102. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiyama T, Nikaido E, Yamaguchi A, Nishino K. Roles of Salmonella multidrug efflux pumps in tigecycline resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:105–110. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Hirao K, Oshima T, Aiba H, Utsumi R, Ishihama A. Functional characterization in vitro of all two-component signal transduction systems from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1448–1456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh GR, Kembou Koungni FC, Paukner A, Stratmann T, Blissenbach B, Schnetz K. BglJ-RcsB heterodimers relieve repression of the Escherichia coli bgl operon by H-NS. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:6456–6464. doi: 10.1128/JB.00807-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giel M, Desnoyer M, Lopilato J. A mutation in a new gene, bglJ, activates the bgl operon in Escherichia coli K-12. Genetics. 1996;143:627–635. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.2.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambalot RH, Gehring AM, Flugel RS, Zuber P, LaCelle M, Marahiel MA, Reid R, Khosla C, Walsh CT. A new enzyme superfamily - the phosphopantetheinyl transferases. Chem Biol. 1996;3:923–936. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(96)90181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring AM, Mori I, Walsh CT. Reconstitution and characterization of the Escherichia coli enterobactin synthetase from EntB, EntE, and EntF. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2648–2659. doi: 10.1021/bi9726584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldheim DA, Chin AM, Nierva CT, Feucht BU, Cao YW, Xu YF, Sutrina SL, Saier MH. Physiological consequences of the complete loss of phosphoryl-transfer proteins HPr and FPr of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system and analysis of fructose (fru) operon expression in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5459–5469. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.5459-5469.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WF, Cheng X, Molineux IJ. Isolation and identification of fxsA, an Escherichia coli gene that can suppress F exclusion of bacteriophage T7. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:485–499. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebbapragada A, Johnson MS, Harding GP, Zuccarelli AJ, Fletcher HM, Zhulin IB, Taylor BL. The Aer protein and the serine chemoreceptor Tsr independently sense intracellular energy levels and transduce oxygen, redox, and energy signals for Escherichia coli behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10541–10546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondijk TH, Fiegen D, Richardson DJ, Cole JA. Roles of NapF, NapG and NapH, subunits of the Escherichia coli periplasmic nitrate reductase, in ubiquinol oxidation. Mol Microbiol. 2002;44:245–255. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troxell B, Fink RC, Porwollik S, McClelland M, Hassan HM. The Fur regulon in anaerobically grown Salmonella enterica sv Typhimurium: identification of new Fur targets. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:236. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baucheron S, Coste F, Canepa S, Maurel MC, Giraud E, Culard F, Castaing B, Roussel A, Cloeckaert A. Binding of the RamR repressor to wild-Type and mutated promoters of the ramA gene involved in efflux-mediated multidrug resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:942–948. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05444-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claret L, Hughes C. Functions of the subunits in the FlhD2C2 transcriptional master regulator of bacterial flagellum biogenesis and swarming. J Mol Biol. 2000;303:467–478. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini S, Slauch JM, Aldridge PD, Rao CV. Role of cross talk in regulating the dynamic expression of the flagellar Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 and type 1 fimbrial genes. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:5767–5777. doi: 10.1128/JB.00624-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubiz JE, Golubeva YA, Lin D, Miller LD, Slauch JM. FliZ regulates expression of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 invasion locus by controlling HilD protein activity in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:6261–6270. doi: 10.1128/JB.00635-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbe TR, Kobayashi M, Yukawa H. Indole-inducible proteins in bacteria suggest membrane and oxidant toxicity. Arch Microbiol. 2000;173:78–82. doi: 10.1007/s002030050012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal T, Alaniz RC, Wood TK, Jayaraman A. The bacterial signal indole increases epithelial-cell tight-junction resistance and attenuates indicators of inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:228–233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906112107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]