Abstract

Background

Depression occurs more commonly during the menopause transition in women with vasomotor symptoms (VMS) than in those without, but most women with VMS do not develop depression. It has been hypothesized that VMS are associated with depression because VMS lead to repeated awakenings, which impair daytime well-being. We aimed to determine if objectively measured sleep and perceived sleep quality are worse in depressed women with VMS than in non-depressed women with VMS.

Methods

Objectively and subjectively measured sleep parameters were compared between 52 depressed women with VMS and 51 non-depressed controls with VMS. Actigraphic measures of objective sleep conducted in the home environment and subjective measures of sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Questionnaire Index [PSQI]) were compared using linear regression models.

Results

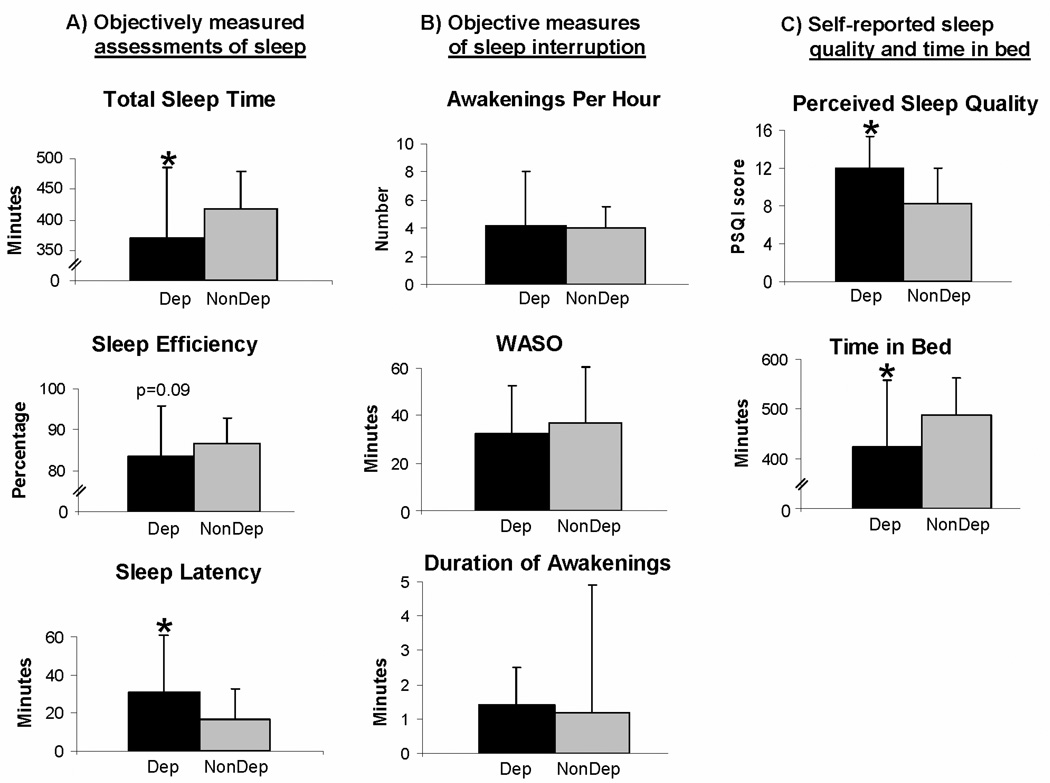

On objective assessments, depressed women with VMS spent less time-in-bed (by 64.8 minutes, p<0.001), and had shorter total sleep time (by 47.7 minutes, p=0.008), longer sleep-onset latency (by 13.8 minutes, p=0.03), and lower sleep efficiency (by 3.2 percentage points, p=0.09), but did not awaken more or spend more time awake after sleep-onset than non-depressed controls with VMS. Depressed women also reported worse sleep quality (mean PSQI 12.0 vs. 8.3, p<0.001). Adjustment for VMS frequency and important demographic characteristics did not alter these associations.

Conclusions

Sleep quality and selected parameters of objectively measured sleep, but not sleep interruption, are worse in depressed than in non-depressed women with VMS. The type of sleep disturbance seen in depressed participants was not consistent with the etiology of depression secondary to VMS-associated awakenings.

Introduction

The risk of depression increases significantly during the perimenopause (1–5) and may continue to be elevated in the early postmenopausal years.(2, 6) Most,(1, 5, 7, 8) but not all,(3, 4) studies have found that depression occurs more commonly during the menopause transition in women who have hot flashes and night sweats, or vasomotor symptoms (VMS), than in those who do not. Even among women with no prior history of psychiatric illness, women with VMS are at greater risk for developing a first lifetime episode of depression than those without VMS.(5)

The basis for the association between VMS and depression is unknown. One hypothesis, termed the “domino hypothesis”, is widely touted as an explanation for the development of depression during the menopause transition. This hypothesis proposes that VMS result in depression because they awaken women repeatedly throughout the night, which consequently impairs daytime well-being.(9, 10) The domino hypothesis assumes a strong relationship between VMS and sleep disturbance. However, evidence of the association between VMS and sleep is conflicting, with results varying based on whether subjective sleep quality or objective sleep parameters were assessed. VMS are strongly associated with poor self-reported sleep quality in peri- and postmenopausal women.(11–19) In a large epidemiologic survey of women with severe VMS, 81.3% reported poor sleep quality and 43.8% met criteria for the clinical disorder of insomnia.(17)

The specific type of sleep disturbance reported by women with VMS involves repeated brief awakenings associated with night sweats.(20) However, studies that measure sleep objectively using polysomnography in healthy postmenopausal women (11, 21–24) and breast cancer patients (25) with VMS do not consistently find that VMS are associated with awakenings. While some studies have found that women with VMS spend time awake after sleep-onset and have more awakenings,(21, 23–25) and/or reduced sleep efficiency,(24, 25) than women without VMS, others report no significant differences in objectively measured sleep parameters between women with and without VMS.(11, 22)

The basis for the strong association between VMS and depression is unknown. While a significant proportion of women with VMS also meets criteria for depression, not all women with VMS become depressed, suggesting that sleep disturbance or other factors may differ between those women with VMS who do and do not become depressed.(8) If the domino hypothesis is correct, variability in the number of nocturnal VMS, the number of awakenings after sleep-onset, and/or the amount of time spent awake after sleep-onset would be expected to influence the likelihood that depression occurs in this population. It is therefore critical to examine the type of sleep disturbance seen in depressed women with VMS to determine if the type of sleep disturbance they experience differs from that of non-depressed women who also have VMS. The purpose of this study was to delineate the type of sleep disturbance observed in depressed women to address the hypothesis that women with VMS and depression have greater disturbance in objectively measured sleep and in subjectively-reported sleep quality than non-depressed controls with VMS.

Methods

Subjects

Subjects were participants enrolled in one of 3 concurrently conducted clinical trials for treatment of VMS in (1) depressed peri- and postmenopausal women with spontaneous VMS, (2) non-depressed peri- and postmenopausal women with spontaneous VMS, and (3) non-depressed women with breast cancer who had VMS induced by anti-estrogen therapies. The two non-depressed groups were treated as one control group because there was no difference between the two groups in subjective sleep quality, time-in-bed, total sleep time, sleep latency, or number of hot flashes reported or measured objectively. In total, 52 women with depression and VMS and 51 non-depressed women (25 with spontaneous VMS and 26 with VMS induced by ant-estrogen therapies) participated in the study.

Subjects were recruited from primary-care, psychiatry, gynecology, and oncology outpatient clinics and the community. All were women ≥ 40-years-old reporting VMS and sleep disturbance associated with VMS who were seeking treatment for VMS. At the time of enrollment, none of them had received treatment with medications which treat VMS, sleep, and depression for at least 2 weeks. Informed consent was obtained from all participants at study entry and study procedures were approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

In addition to VMS and associated sleep disturbance, depressed and control subjects were required to have menstrual-cycle irregularities consistent with the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop criteria for late menopause transition (≥ one cycle in past year but skipped > 2 cycles) or postmenopausal status (amenorrhea > 12 months).(26) Breast cancer controls were required to have developed VMS on anti-estrogen therapy (85% were on tamoxifen, 15% on aromatase inhibitors; median duration of use 17 months, range 2–54 months) rather than from natural menopause. However, the majority (77%) of breast cancer participants were peri- or postmenopausal. Breast cancer patients had been diagnosed 36 ± 24 months prior to enrollment and all had completed chemotherapy and radiation therapy ≥ 3 months previously.

Except for depression criteria, all other study inclusion criteria were identical for depressed subjects and non-depressed controls: (1) ≥ 14 VMS per week for ≥ 2 weeks; (2) awakenings that began when VMS developed; (3) ≥ awakenings associated with VMS per night occurring ≥ 3 nights per week; (4) no current or recent use of psychiatric medications, sleep medications, or exogenous hormones; and (5) no diagnosis of sleep apnea, periodic limb movement disorder, or narcolepsy. The presence of VMS (≥ 14 VMS per week) was confirmed prospectively with a 7-day diary.

Sleep symptoms were evaluated to be unrelated to primary sleep disorders using a clinical interview and standard cut-off scores on the Sleep Disorders Questionnaire (SDQ) for sleep apnea, periodic limb movement disorder, and narcolepsy.(27) All participants met research diagnostic criteria for an insomnia syndrome for ≥ one month, with a deleterious impact of sleep disruption on daytime well-being or function.(28)

Subjects were classified as having depression if they met diagnostic criteria for one of three depression diagnoses (major depression, minor depression, or dysthymia). The temporal sequence between the onset of VMS and the depression disorder was not specified. A depression diagnosis was confirmed to be present in depressed subjects and to be absent in non-depressed controls based on the clinician-rated Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID)(29) and self-administered Patient Health Questionnaire.(30) The diagnosis of a depressive disorder with the SCID requires that sadness and/or lack of pleasure be present in addition to several neurovegative symptoms of depression (e.g., fatigue). Use of this standardized approach to depression categorization restricted the depressed group to those who met criteria for a depression disorder, rather than also including women who have daytime symptoms resulting from sleep deprivation (e.g., fatigue). Women were excluded from participating in this study if they had psychotic symptoms, suicidal ideation, or met criteria for bipolar, psychotic, anxiety, eating, alcohol, or drug abuse disorders.

Procedures

The study involved a one-week cross-sectional assessment of VMS, sleep disturbance, and mood. VMS and sleep parameters were measured objectively in participants’ homes for 2 consecutive nights during a 7-day period in which a subjective VMS diary and sleep quality assessments were completed. Participants were instructed to maintain routine sleep habits during the study.

Sleep

Objective sleep parameters were assessed using an actigraphic watch (Mini Mitter Co., Inc, Bend, OR), which was worn for 2 nights in each participant’s home, maintaining their natural sleeping environment. Actigraphic sleep assessments identify sleep and wake states based on measurements of motor-activity acceleration that have been standardized against polysomnography.(31–36)

Actigraphic watches were worn on the wrist of the non-dominant hand. Data were collected in 30-second epochs, with an awake state defined when the total activity count exceeded a sensitivity threshold of 80 activity counts during each epoch, a threshold that correlates strongly with wake status as defined by polysomnography.(24) Subjects pushed event-markers on the watch to indicate when they got into bed and when they got out of bed in the morning to calculate the amount of time that they spent in bed (time-in-bed). These event markers were used together with the Actiwatch software to calculate objective assessments of total sleep time (amount of actual time spent asleep), sleep efficiency (proportion of time-in-bed that is filled by sleep), and sleep-onset latency (time to fall asleep at beginning of the night). Actigraphy was also used to determine objective measurements of sleep interruption, including wake time after sleep-onset (amount of time spent awake after falling asleep at the beginning of the night and waking up in the morning), and the number and average duration of awakenings.

Subjective sleep quality was assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Questionnaire Index (PSQI), a widely administered 19-item self-rated questionnaire that measures quality of sleep over the past month (range 0–21, higher score worse).(37) PSQI scores > 5 distinguish poor sleepers from good sleepers.(37)

Vasomotor symptoms (VMS)

Nocturnal VMS frequency was measured using ambulatory sternal skin-conductance monitoring, a validated physiologic measure of VMS.(38, 39) The Biolog ambulatory skin-conductance monitor (UFI, Morro Bay, CA) is a lightweight, portable single-channel device that samples skin-conductance at 1 Hz via two Medi-trace sliver/silver chloride electrodes filled with 0.05 M potassium chloride Unibase/glycol paste that are affixed to the sternum. Conventional VMS criteria of an increase of ≥ 2 µmho within 30 seconds (20-minute minimum interflash scoring interval) were applied.(38, 39) The µmho unit of measurement of skin-conductance is the inverse of ohm, a common measure of electrical resistance.

Participants wore the skin-conductance monitor in their own home for two consecutive nights concurrent with the actigraphic monitor to determine the relationship between individual hot flashes and awakenings, and to establish a reliable estimate of both VMS and objectively measured sleep parameters,(40, 41) while minimizing participant burden. The skin-conductance monitor was programmed to be time-synched with the actigraphic watch. Any hot flash recorded between bedtime and wake-up time was defined as an objectively measured nocturnal VMS.

In addition to objective hot flash monitoring, VMS occurring during the day and night were also reported subjectively with the widely used 7-day North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG) diary.(42) Participants reported the number and severity of hot flashes experienced during the daytime at the end of day and the number and severity of hot flashes experienced during the night upon awakening in the morning. VMS were assessed both objectively and subjectively because the correlation between these assessment methods is limited, with women tending to under-report VMS relative to the number that are measured objectively.(15, 43)

Additional assessments

In addition to undergoing a structured psychiatric diagnostic evaluation, all participants completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (44) to measure the severity of depressive symptoms among those with versus without a clinical diagnosis of depression. The BDI is a well-validated and widely-used self-administered 21-item questionnaire that assesses the severity of depressive symptoms over the past 7 days (range 0–63, higher score worse) was used to measured depressive symptoms during the study.

Overall quality-of-life was also assessed to determine if the presence of depression is associated with worse sense of well-being, even among women with bothersome VMS and sleep disturbance. Quality-of-life was assessed with the Quality-of-Life Inventory (QOLI), a 16-item, self-administered instrument (range 0–100%, lower score worse) that addresses multiple different life domains (health, work, recreation, friendships, love relationships, home, self-esteem, and standard of living), rather than menopause- or health-related symptoms of VMS, sleep, and mood.(45, 46) Height and weight were measured in order to calculate body-mass index (BMI).

Hormone analysis

Serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels were measured in the Massachusetts General Hospital Reproductive Endocrine Laboratory using a two-site monoclonal non-isotopic system according to the manufacturer’s directions (Axsym, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA), as previously described,(47, 48) and expressed in IU per liter as equivalents of the Second International Pituitary Standard 78/549. The interassay coefficients of variation (CVs) are 5.2, 4.6 and 5.5% for quality control sera containing 7.4, 15.6 and 42.0 IU/liter, respectively. FSH levels were obtained to support the clinical determination of peri- and postmenopausal status as the source of VMS and to confirm peri/postmenopausal status among women who had undergone a hysterectomy only. FSH levels were not drawn in breast cancer patients because the etiology of VMS was required to be the anti-estrogen therapy and not menopause.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in objectively measured sleep parameters and perceived sleep quality between depressed subjects and controls were examined using Student’s t-tests for normally distributed data and Wilcoxon non-parametric tests for non-normal data. For outcomes recorded over 2 nights—that is, objectively measured VMS frequency and sleep parameters (total sleep time, time-in-bed, sleep efficiency, sleep-onset latency, time awake after sleep-onset, number and duration of awakening), an average of the 2 nights was calculated for each subject and treated as the outcome variable, in order to obtain a more stable estimate for each participant (40, 41). For sleep outcomes that differed between depressed subjects and controls, multiple linear regression models were built with each sleep outcome of interest as the dependent measure and depression status as the independent variable. Models were then adjusted for hot flash frequency (first objectively and then subjectively measured) and, after candidate variables were selected based upon content expertise (age, race, BMI, menopause status, and FSH), those demographic factors that differed between depressed and non-depressed participants at p<0.10 (race, BMI, and menopause status) were included in final models. No interactions were tested.

Adjustments for multiple comparisons were not made because we were testing hypotheses about the association between depression and distinct parameters of sleep disturbance in this population.(49) Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX), and statistical significance was set at α=0.05.

Results

Characteristics of study subjects

Depressed subjects (n=52) met diagnostic criteria for major depression (69.2%), dysthymia (17.3%) and minor depression (13.5%). Compared with non-depressed women (n=51), depressed participants had more depression symptoms (median BDI 18, interquartile range [IQR] 12–23 vs. 4, IQR 1–9, p<0.001) and worse quality-of-life (QOLI 16%, IQR 3–49% vs. 55%, IQR 34–90%; p<0.001), consistent with the diagnosis of a depression disorder.

The groups did not differ in age and were mainly Caucasian, although fewer depressed women were Caucasian (p=0.01). More depressed than non-depressed women were overweight or obese (p=0.003). Elevated FSH levels confirmed peri/postmenopausal status, but more women in the depressed group were perimenopausal while more in the non-depressed group were postmenopausal (p<0.001).

The frequency of VMS did not differ between depressed and non-depressed subjects, regardless of whether they were assessed objectively using the skin-conductance monitor or subjectively using the VMS diary (Table 1). Depressed women reported experiencing a median of 5.2 VMS over a 24-hour period and a median of 2.4 VMS during the night on a 7-day diary and objective monitoring detected a median of one hot flash per night. Similarly, non-depressed women reported 7.0 VMS per 24 hours, 2.7 VMS during the night, and objective monitoring detected a median of one hot flash per night. There was no significant difference between the depressed and non-depressed groups in the proportion of VMS that was associated with an awakening, based on a 2-minute interval between the hot flash and awakening used in previous studies.(22)

Table 1.

Characteristics of women with vasomotor symptoms (VMS) with and without depressive disorders.

| Depressed women (n=52) |

Non-depressed controls (n=51) |

p- value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| mean ± SD |

mean ± SD |

||

| Age (yrs) | 50.8 ± 4.9 | 52.3 ± 8.0 | NS |

| % Caucasian | 37 (71.2%) | 47 (92.2%) | 0.01 |

| Body-mass index (kg/m2) | 0.003 | ||

| Normal (<25) | 6 (12%) | 20 (39%) | |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 13 (25%) | 13 (26%) | |

| Obese (≥30) | 33 (63%) | 18 (35%) | |

| Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH, IU/L) | 95.5 ± 63.1 | 87.5 ± 36.5 b | NS |

| Menopause status | <0.001 | ||

| Premenopausal | - | 5 (10%) a | |

| Perimenopausal | 18 (46%) | 3 (6%) | |

| Postmenopausal | 30 (57%) | 41 (80%) | |

| Hysterectomy with FSH > 20 IU/L | 4 (7%) | 2 (4%) | |

| Median (interquartile range) |

Median (interquartile range) |

||

| Vasomotor symptoms (VMS) | |||

| # reported/24 hours c | 5.2 (3.0–8.7) | 7.0 (4.4–11.2) | NS |

| # reported during night c | 2.4 (1.4–3.2) | 2.7 (1.4–8.2) | NS |

| # measured during night d | 1.0 (0–3.0) | 1.0 (0–3.0) | NS |

|

% of measured VMS associated with an awakening e |

83.3 (36.7–100) | 90.0 (70.0–100) | NS |

NS = non-significant.

Includes breast cancer patients with iatrogenic VMS.

Non-depressed non-iatrogenic patients only (n=25).

Average number of daily VMS reported during one week using the North Cancer Central Treatment Group VMS diary (n=44).

Average of two nights when nocturnal VMS were monitored physiologically during actigraphic sleep monitoring standardized to a 7-hour night of sleep.

N=31.

Comparison of objective and subjective sleep measures between depressed vs. non-depressed women with VMS (Table 2)

Table 2.

Objective sleep parameters and subjective sleep quality in depressed and non-depressed women with vasomotor symptoms (VMS).

| Depressed women (n=52) |

Non-depressed controls (n=51) |

Unadjusted coefficient (SEa) |

Unadjusted p value |

Adjusted coefficient (SEa) |

Adjusted p valueb |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sleep time (min.) | 370.8 ± 114.2 | 418.5 ± 60.5 | −46.7 (17.2) | 0.008 | −45.6 (21.1) | 0.04 |

| Time-in-bed (min.) | 423.6 ± 134.1 | 488.4 ± 73.4 | −64.9 (22.1) | 0.004 | −49.6 (35.5) | NS |

| Sleep efficiency (%) | 83.4 ± 12.2 | 86.6 ± 6.1 | −3.2 (1.9) | 0.09 | −3.1 (2.2) | NS |

| Sleep-onset latency (min.) | 30.7 ± 40.3 | 16.9 ± 16.0 | 13.8 (6.1) | 0.03 | 18.9 (8.1) | 0.03 |

| Wake time after sleep onset (min.) | 32.3 ± 20.5 | 36.9 ± 23.5 | −4.6 (4.4) | NS | −9.0 (5.2) | NS |

| Awakening per hour | 4.2 ± 3.8 | 4.0 ± 1.5 | 0.2 (0.6) | NS | 0.5 (0.9 ) | NS |

| Duration of awakenings (min.) | 1.4 ± 1.1 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.2 (0.2) | NS | −0.01 (0.1 ) | NS |

| Perceived sleep quality c | 12.0 ± 3.3 | 8.3 ± 3.7 | 3.7 (0.7) | <0.001 | −3.8 (1.0) | <0.001 |

NS=not significant.

Regression coefficient (and standard error) for the depressed versus the non-depressed group.

Models adjusted for number of VMS, race, body-mass index, and menopause status include ≥68 participants.

Perceived sleep quality measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Questionnaire Index (PSQI, range 0–21, higher score worse).(37)

Objective assessments of selected parameters of sleep were worse in depressed than in non-depressed women (Figure 1A). Depressed women with VMS had shorter total sleep time (by 47.7 minutes, p=0.008) and longer sleep-onset latency (by 13.8 minutes, p=0.03) than non-depressed controls. There was a trend toward statistical significance for a lower sleep efficiency (by 3.2 percentage points, p=0.09) in women with depression. However, there was no difference between depressed and non-depressed subjects in objective measures of sleep interruption (Figure 1B); depressed subjects did not spend more time awake after sleep-onset than non-depressed controls, nor did they awaken more frequently or spend more time awake with each awakening.

Figure 1.

Mean and standard deviation of (A) objectively measured assessments of selected sleep parameters (total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and sleep-onset latency), (B) objective measures of sleep interruption (number of awakenings/hour, wake-time after sleep-onset, and mean duration of awakenings) specifically, and (C) self-reported sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Questionnaire Index, PSQI, range 0–21, higher score implies worse sleep quality)(37) and time-in-bed in women with vasomotor symptoms who were depressed (Dep) and non-depressed (NonDep).

* p<0.05

Subjective measures of sleep (Figure 1C) revealed that depressed women perceived worse sleep quality than non-depressed women (PSQI 12.0 ± 3.3 vs. 8.3 ± 3.7, respectively, p<0.001), with PSQI scores > 5 in 96% of depressed subjects, compared with 69% in controls (p<0.001). In addition, depressed subjects spent less time-in-bed than non-depressed women (by 64.8 minutes, p<0.001), based on real-time event markers on the actigraphic watch. Using event-markers used to record final wake-up time, depressed women indicated waking up an average of 17 minutes earlier than non-depressed women, a difference that was not statistically significantly different (6:25am ± 83 minutes vs. 6:42am ± 76 minutes, respectively; p=0.16), suggesting that they did not have early-morning awakening. However, there was a significant difference between the bedtime of depressed and non-depressed women, with depressed women getting into bed an average of 36 minutes later than non-depressed women (11:42pm ± 105 minutes vs. 11:06pm ± 80 minutes, respectively; p=0.008),

The difference in objectively measured sleep outcomes and subjective perception of sleep quality remained significant after adjusting for the number of VMS (regardless of whether measured subjectively or objectively). In these bivariate models, depression was associated with a shorter total sleep time (p=0.01), longer sleep-onset latency (p=0.04), less time-in-bed (p=0.01), and the perception of worse sleep quality (p<0.001). There was no significant relationship between VMS and any of these sleep outcomes in adjusted models. Further adjustment for demographic factors that differed between depressed and non-depressed women (race, BMI, and menopause status) did not alter the strong association between depression and sleep measures (Table 2), with the depressed group continuing to have a shorter total sleep time (p=0.04), longer sleep-onset latency (p=0.03), and perception of worse sleep quality (p<0.001). No association was found between depression and either sleep efficiency or time-in-bed after adjustment for VMS, race, BMI, and menopause status.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that there are important differences in objectively measured sleep parameters and perceived sleep quality between depressed and non-depressed peri- and postmenopausal women with vasomotor symptoms and sleep disturbance. Depressed women spent less time-in-bed and had shorter total sleep time, longer sleep-onset latency, and a trend toward lower sleep efficiency than non-depressed women, but measurements of sleep interruption (wake time after sleep onset, number of awakenings, duration of awakenings) did not differ between depressed and non-depressed participants. Depressed women also reported that they had worse perceived sleep quality than non-depressed women with VMS. The association between depression and worse sleep was seen despite a comparable frequency of nocturnal VMS in the two groups.

Our results do not lend support to the domino hypothesis as an explanation for the development of depression during the menopause transition because the type of sleep disturbance that differentiated depressed from non-depressed women did not include interruption of sleep that is typically associated with hot flashes. We did not observe an increased frequency of nocturnal VMS, more awakenings or more time spent awake after sleep-onset, which would be predicted by the domino hypothesis to explain that depression develops in peri- and postmenopausal women because VMS interrupt sleep.

If sleep is involved as an intermediate factor between VMS and depression, other measures of sleep fragmentation or changes in sleep architecture that cannot be detected by actigraphy may be involved. It is also plausible that the relatively low number of hot flashes reported and measured per night in our study population limits our ability to detect the impact of VMS on sleep. However, the number of nocturnal VMS reported is representative of the general population with VMS,(50) a proportion of whom will also experience depression. Our results do not exclude the possibility that VMS may exacerbate the sleep disturbance of depression and/or that factors which cause VMS, such as estrogen withdrawal, may concurrently result in insomnia and depression in susceptible women. Definitive evidence of a causal pathway between VMS, sleep disturbance and depression requires a more direct mechanistic study and cannot be established with this cross-sectional study design.

While the depressed participants spent on average one hour less time-in-bed than the non-depressed women, they did not have shorter sleep-onset latency or better sleep efficiency than the non-depressed group, which is the expected compensatory response to sleep deprivation resulting from less time spent in bed among healthy individuals.(51) In contrast, our depressed subjects showed the opposite effect—longer sleep-onset latency and a trend toward lower sleep efficiency, consistent with a significant abnormality of sleep seen in the clinical disorder of insomnia.(28) Thus, the depressed subjects had significant insomnia, involving a perception of sleep quality that is disproportionately worse than what is measured objectively.

Our work expands on previous studies which have found that peri- and postmenopausal women with VMS and mild depressive symptoms report perceiving worse sleep quality than those with VMS alone.(15, 52) However, unlike studies which found that objectively measured sleep does not differ between those with and without depressive symptoms in postmenopausal women,(52) we found important differences in objectively measured sleep. Our study results may differ because we included women with clinically relevant depressive disorders, rather than only mild depressive symptoms. By specifically comparing sleep parameters in women with versus without clinical depression, our work drew greater contrast between the two groups of women and provides stronger evidence that mood disturbance is associated with sleep abnormalities among women with VMS.

The clinical disorder of depression can involve difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, and/or early-morning awakening on objective monitoring and reduced sleep quality on subjective assessments.(53) Indeed, our study found that depressed women with VMS got into bed later and had more problems falling asleep, but not more problems staying asleep or early-morning awakening, than non-depressed women with VMS. Sleep disturbance is both a symptom manifestation of depression,(53) and increases the likelihood that depression will develop.(54) Thus the temporal relationship between sleep disturbance and depression is complex and can be bi-directional, with sleep disturbance either preceding or following the onset of depression. However, because ours is a cross-sectional study, we are unable to determine if the depressed participants had worse sleep as a symptom manifestation of their depression, or if these women developed depression as a result of greater sleep disturbance. The relationship between VMS and depression may similarly be bi-directional, with some recent studies suggesting that depression symptoms can at times precede, rather than follow, the development of VMS.(55) Future studies that assess the temporal relationship between VMS, sleep and mood prospectively are needed to determine if there is a causal pathway between these core menopause-related symptoms.

Our results no not provide information about the extent to which VMS disrupts sleep as we did not include a control group without VMS. Several studies which do address the impact of VMS on sleep have reported that women with VMS have reduced sleep efficiency,(24, 25) or more awakenings and time-awake after sleep-onset,(21, 23–25) while still others have found that objectively measured sleep did not differ between those with and without VMS.(11, 22)

Our non-depressed control group was divided equally between women with spontaneous VMS and those with VMS induced by anti-estrogen therapy. Women with breast cancer had been diagnosed an average of 3 years prior to study enrollment and were not undergoing chemotherapy or radiation treatment at the time of the study. While merging this control group introduces some heterogeneity, there was no difference between these subgroups in subjective sleep quality (PSQI), time-in-bed, total sleep time, sleep latency, or number of hot flashes reported or measured objectively. These findings suggest that VMS induced by anti-estrogens are not associated with worse sleep than spontaneous VMS seen in peri- and postmenopausal women.

An important strength of the current study it that we used both subjective and objective assessment methods to measure VMS and sleep parameters. Some studies have measured sleep, but not VMS, objectively,(52) while others have measured VMS, but not sleep, objectively.(15) Objective measurements are important to obtain in studies examining the association between depression and other subjectively reported symptoms because depression can influence reporting of both sleep (53) and VMS.(15) It is notable that both depressed and non-depressed women in our study reported experiencing more VMS at night than were detected objectively. This finding is in contrast to other studies, in which more nocturnal VMS were measured objectively than were reported subjectively in healthy peri- and postmenopausal women (15) and women with breast cancer.(43) However, unlike other studies of nocturnal VMS,(15, 43) our study selected women who reported experiencing sleep disturbance in conjunction with their VMS, which may influence the relationship between the number of VMS that are perceived versus detected during the night. Regardless, associations between depression and sleep disturbance were observed whether nocturnal VMS were measured subjectively or objectively.

Another study strength is the use of objective measures in an ambulatory setting. Because we conducted objective sleep assessments in the participants’ natural sleeping environment and instructed them to maintain their usual sleep habits, our assessments are more representative of the participants’ true sleep than would be seen in the sleep laboratory setting. This approach to objective sleep monitoring enabled us to detect the reduced time spent in bed in the depressed women, an important parameter of sleep disturbance that has not been previously described and would not have been identified in the laboratory setting in which time-in-bed is determined by the sleep center.

In addition to its strengths, this study is limited by the inclusion of a sample of opportunity of women enrolled in three separate clinical trials who were evaluated cross-sectionally. Although eligibility criteria in the trials were designed in parallel in order to make comparisons between these groups of women, there were some differences between the groups (i.e., race, menopause status, and BMI). However, these characteristics did not influence the strong association between depression and sleep disturbance in adjusted regression models. The cross-sectional design of the study also limits the causal inferences that can be made about the influence of depression on sleep in women with VMS. Another potential limitation intrinsic to actigraphic assessment is that it can score quiet time as being asleep when an individual is awake in bed and not moving.(56) Polysomnographic corroboration is required to definitively establish whether differences in objectively measured sleep that we observed can be explained in part by differences in the amount of quiet time spent in bed between depressed and non-depressed women.

In summary, the type of sleep disturbance that differentiated depressed women with VMS from non-depressed women with VMS involved getting into bed later, problems falling asleep, and spending less time-in-bed and less time asleep, rather than greater interruption of sleep that is typically attributed to hot flashes and proposed in the domino hypothesis (9, 10) to explain the occurrence of depression during the menopause transition. Our data suggest that the nature of the sleep disturbance occurring in depressed women with VMS is more complex than previously thought. Clinicians treating women with VMS should be attentive to the type of sleep disturbance reported. Although, peri- and postmenopausal women with VMS are more likely to report worse problems with reduced sleep quality and repeated awakening from sleep than those without VMS,(20) women who report spending less time in bed, less time asleep, and/or problems falling asleep at the beginning of the night should be evaluated for concurrent depression. Our results inform clinical care by emphasizing the importance of focusing treatment on symptoms of sleep disturbance, rather than VMS, concurrent with therapies aimed at managing depression in symptomatic peri- and postmenopausal women.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Brittny Somley, BA, Kate Silver-Heilman, BA, and Erica Pasciullo, BA, for their assistance in data collection and analysis.

Supported in part by: NIMH K23 MH066978, Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation Award, and GlaxoSmithKline

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interests: See attached

References

- 1.Avis N, Brambilla D, McKinlay S, Vass K. A longitudinal analysis of the association between menopause and depression: Results from the Mass. Women's Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1994;4:214–220. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)90099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bromberger JT, Matthews KA, Schott LL, Brockwell S, Avis NE, Kravitz HM, Everson-Rose SA, Gold EB, Sowers M, Randolph JF., Jr Depressive symptoms during the menopausal transition: The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) J Affect Disord. 2007;103(1–3):267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Nelson DB. Associations of hormones and menopausal status with depressed mood in women with no history of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(4):375–382. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Liu L, Gracia CR, Nelson DB, Hollander L. Hormones and menopausal status as predictors of depression in women in transition to menopause. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(1):62–70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen LS, Soares CN, Vitonis AF, Otto MW, Harlow BL. Risk for new onset of depression during the menopausal transition: the Harvard study of moods and cycles. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(4):385–390. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maartens LW, Knottnerus JA, Pop VJ. Menopausal transition and increased depressive symptomatology: a community based prospective study. Maturitas. 2002;42(3):195–200. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(02)00038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daly RC, Danaceau MA, Rubinow DR, Schmidt PJ. Concordant restoration of ovarian function and mood in perimenopausal depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(10):1842–1846. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joffe H, Hall J, Soares C, Hennen J, Reilly C, Carlson K, Cohen L. Vasomotor symptoms are associated with depression in perimenopausal women seeking primary care. Menopause. 2002;9(6):392–398. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200211000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell S, Whitehead M. Oestrogen therapy and the menopausal syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1977;4(1):31–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bachmann GA. Vasomotor flushes in menopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(3 Pt 2):S312–S316. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70725-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young T, Rabago D, Zgierska A, Austin D, Laurel F. Objective and subjective sleep quality in premenopausal, perimenopausal, and postmenopausal women in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Sleep. 2003;26(6):667–672. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.6.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kravitz HM, Ganz PA, Bromberger J, Powell LH, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Meyer PM. Sleep difficulty in women at midlife: a community survey of sleep and the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2003;10(1):19–28. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200310010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaver J, Giblin E, Lentz M, Lee K. Sleep patterns and stability in perimenopausal women. Sleep. 1988;11(6):556–561. doi: 10.1093/sleep/11.6.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaver JL, Zenk SN. Sleep disturbance in menopause. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9(2):109–118. doi: 10.1089/152460900318605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thurston RC, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Sherwood A. Association between hot flashes, sleep complaints, and psychological functioning among healthy menopausal women. Int J Behav Med. 2006;13(2):163–172. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1302_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dennerstein L, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, Guthrie JR, Burger HG. A prospective population-based study of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(3):351–358. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00930-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohayon MM. Severe hot flashes are associated with chronic insomnia. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(12):1262–1268. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.12.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Gracia CR, Pien GW, Nelson DB, Sheng L. Symptoms associated with menopausal transition and reproductive hormones in midlife women. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 Pt 1):230–240. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000270153.59102.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freedman RR, Roehrs TA. Sleep disturbance in menopause. Menopause. 2007 doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e3180321a22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erlik Y, Tataryn IV, Meldrum DR, Lomax P, Bajorek JG, Judd HL. Association of waking episodes with menopausal hot flushes. JAMA. 1981;245(17):1741–1744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erlik Y, Tataryn IV, Meldrum DR, Lomax P, Bajorek JG, Judd HL. Association of waking episodes with menopausal hot flushes. JAMA. 1981;245(17):1741–1744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freedman RR, Roehrs TA. Lack of sleep disturbance from menopausal hot flashes. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(1):138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freedman RR, Roehrs TA. Effects of REM sleep and ambient temperature on hot flash-induced sleep disturbance. Menopause. 2006;13(4):576–583. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000227398.53192.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woodward S, Freedman RR. The thermoregulatory effects of menopausal hot flashes on sleep. Sleep. 1994;17(6):497–501. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.6.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savard J, Davidson JR, Ivers H, Quesnel C, Rioux D, Dupere V, Lasnier M, Simard S, Morin CM. The association between nocturnal hot flashes and sleep in breast cancer survivors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27(6):513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soules MR, Sherman S, Parrott E, Rebar R, Santoro N, Utian W, Woods N. Executive summary: Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) Fertil Steril. 2001;76(5):874–878. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02909-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Douglass AB, Bornstein R, Nino-Murcia G, Keenan S, Miles L, Zarcone VP, Jr, Guilleminault C, Dement WC. The Sleep Disorders Questionnaire. I: Creation and multivariate structure of SDQ. Sleep. 1994;17(2):160–167. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edinger JD, Bonnet MH, Bootzin RR, Doghramji K, Dorsey CM, Espie CA, Jamieson AO, McCall WV, Morin CM, Stepanski EJ. Derivation of research diagnostic criteria for insomnia: report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Work Group. Sleep. 2004;27(8):1567–1596. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for the DSM-IV Axis I disorders - patient edition. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jean-Louis G, von Gizycki H, Zizi F, Spielman A, Hauri P, Taub H. The actigraph data analysis software: I. A novel approach to scoring and interpreting sleep-wake activity. Percept Mot Skills. 1997;85(1):207–216. doi: 10.2466/pms.1997.85.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jean-Louis G, von Gizycki H, Zizi F, Spielman A, Hauri P, Taub H. The actigraph data analysis software: II. A novel approach to scoring and interpreting sleep-wake activity. Percept Mot Skills. 1997;85(1):219–226. doi: 10.2466/pms.1997.85.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jean-Louis G, Zizi F, von Gizycki H, Hauri P. Actigraphic assessment of sleep in insomnia: application of the Actigraph Data Analysis Software (ADAS) Physiol Behav. 1999;65(4–5):659–663. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sadeh A, Hauri PJ, Kripke DF, Lavie P. The role of actigraphy in the evaluation of sleep disorders. Sleep. 1995;18(4):288–302. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.4.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kushida CA, Chang A, Gadkary C, Guilleminault C, Carrillo O, Dement WC. Comparison of actigraphic, polysomnographic, and subjective assessment of sleep parameters in sleep-disordered patients. Sleep Medicine. 2001;2:389–396. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blood ML, Sack RL, Percy DC, Pen JC. A comparison of sleep detection by wrist actigraphy, behavioral response, and polysomnography. Sleep. 1997;20(6):388–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CFd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA, Freedman RR, Munn R. Feasibility and psychometrics of an ambulatory hot flash monitoring device. Menopause. 1999;6(3):209–215. doi: 10.1097/00042192-199906030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Freedman RR. Laboratory and ambulatory monitoring of menopausal hot flashes. Psychophysiology. 1989;26(5):573–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1989.tb00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wohlgemuth WK, Edinger JD, Fins AI, Sullivan RJ., Jr How many nights are enough? The short-term stability of sleep parameters in elderly insomniacs and normal sleepers. Psychophysiology. 1999;36(2):233–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buysse DJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Edinger JD, Lichstein KL, Morin CM. Recommendations for a standard research assessment of insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29(9):1155–1173. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.9.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sloan JA, Loprinzi CL, Novotny PJ, Barton DL, Lavasseur BI, Windschitl H. Methodologic lessons learned from hot flash studies. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(23):4280–4290. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.23.4280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carpenter JS, Monahan PO, Azzouz F. Accuracy of subjective hot flush reports compared with continuous sternal skin conductance monitoring. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(6):1322–1326. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000143891.79482.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frisch MB, Cornell J, Villaneuva M. Clinical validation of the Quality of Life Inventory: A measure of satisfaction for in treatment planning and outcome assessment. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:92–101. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frisch MB. Manual and Treatment Guide for the Quality of Life Inventory. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Welt CK, Pagan YL, Smith PC, Rado KB, Hall JE. Control of follicle-stimulating hormone by estradiol and the inhibins: critical role of estradiol at the hypothalamus during the luteal-follicular transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(4):1766–1771. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Welt CK, McNicholl DJ, Taylor AE, Hall JE. Female reproductive aging is marked by decreased secretion of dimeric inhibin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:105–111. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.1.5381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rothman KJ. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology. 1990;1(1):43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thurston RC, Bromberger JT, Joffe H, Avis NE, Hess R, Crandall CJ, Chang Y, Green R, Matthews KA. Beyond frequency: who is most bothered by vasomotor symptoms? Menopause. 2008 doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318168f09b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosenthal L, Roehrs TA, Rosen A, Roth T. Level of sleepiness and total sleep time following various time in bed conditions. Sleep. 1993;16(3):226–232. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Regestein QR, Friebely J, Shifren JL, Scharf MB, Wiita B, Carver J, Schiff I. Self-reported sleep in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2004;11(2):198–207. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000097741.18446.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riemann D, Berger M, Voderholzer U. Sleep and depression--results from psychobiological studies: an overview. Biol Psychol. 2001;57(1–3):67–103. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(01)00090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Riemann D, Voderholzer U. Primary insomnia: a risk factor to develop depression? J Affect Disord. 2003;76(1–3):255–259. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gold EB, Colvin A, Avis N, Bromberger J, Greendale GA, Powell L, Sternfeld B, Matthews K. Longitudinal analysis of the association between vasomotor symptoms and race/ethnicity across the menopausal transition: Study of women's health across the nation. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1226–1235. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ancoli-Israel S, Cole R, Alessi C, Chambers M, Moorcroft W, Pollak CP. The role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep. 2003;26(3):342–392. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]