Abstract

Oral streptococci are able to produce growth-inhibiting amounts of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as byproduct of aerobic metabolism. Several recent studies showed that the produced H2O2 is not a simple byproduct of metabolism but functions in several aspects of oral bacterial biofilm ecology. First, the release of DNA from cells is closely associated to the production of H2O2 in Streptococcus sanguinis and Streptococcus gordonii. Extracellular DNA is crucial for biofilm development and stabilization and can also serve as source for horizontal gene transfer between oral streptococci. Second, due to the growth inhibiting nature of H2O2, H2O2 compatible species associate with the producers. H2O2 production therefore might help in structuring the initial biofilm development. On the other hand, the oral environment harbors salivary peroxidases that are potent in H2O2 scavenging. Therefore, the effects of biofilm intrinsic H2O2 production might be locally confined. However, taking into account that 80% of initial oral biofilm constituents are streptococci, the influence of H2O2 on biofilm development and environmental adaptation might be under appreciated in current research.

1. The Oral Biofilm: A Highly Adapted Microbial Consortium

Oral bacteria residing in the supragingival biofilm have a remarkable degree of structural organization [1, 2]. This organization is the result of a successive buildup and continuous integration of new species into the developing biofilm. Starting with a cleaned or recently emerged tooth, initial oral streptococcal colonizers adhere via specific surface proteins to salivary proteins covering the tooth surface [1]. Oral streptococci by themselves provide surface proteins for the attachment and integration of other oral bacteria [3]. Initial binding of oral streptococci therefore sets the stage for the development of a mature biofilm community. Beside the physical contact, biofilm development involves several layers of interactions among the biofilm community members. This includes efficient nutrient usage by metabolic cooperativity, communication by small signal molecules, and genetic exchange [4, 5].

The crucial steps in initial attachment and biofilm development have been well documented in the past years. Using specific removable appliances harboring dental enamel chips, Diaz et al. were able to trace the spatiotemporal pattern of oral biofilm formation in the human host [6]. Oral streptococci were the predominant species in the initial colonization stage after 4 and 8 hours. Up to 80% of the detected initial colonizers belonged to the genus Streptococcus with some species discussed as constant members presenting a core group of initial biofilm formation [6, 7]. The biofilm developmental process starts with small microcolonies consisting mainly of streptococci and few non-streptococci [6]. This developmental process has implications on other species efforts to join the biofilm community or attach in close proximity. Oral streptococci are known for their production and secretion of antimicrobial substances, one of them is hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [8, 9]. The production of antimicrobial substances like H2O2 could therefore be regarded as an important protection mechanism of the initial colonizers of the resident biofilm community against invading and competing species. More importantly, it might also be a mechanism to shape the colonization process toward a specific species composition. Only species coevolved with oral streptococci and therefore adapted to withstand H2O2 can integrate or colonize in close proximity to the initial colonizers and extend the developing biofilm community.

After initial attachment of streptococci, the biofilm builds up and several other species join the biofilm community [1, 6]. This also leads to an increase in biofilm thickness and subsequent anaerobic conditions [10–12], which in turn can attract anaerobic bacteria. H2O2 production inside the oral biofilm most likely declines under these conditions due to insufficient oxygen availability. The role of H2O2 becomes less important and other factors might influence biofilm maturation. From the perspective of the oral streptococci, H2O2 fulfills its purpose exactly when it is needed, during initial biofilm formation, when oxygen for H2O2 production is readily available [13]. The ecological niche of oral streptococci is freely accessible for competing species during initial biofilm formation, and this competition is counteracted either by the direct bactericidal effect of H2O2 or the preferred integration of compatible species into the growing community. Once the streptococci are established and have built up an association of compatible neighboring biofilm inhabitants, they already occupy their favorite ecological niche and the antimicrobial activity of H2O2 is no longer required.

The multispecies oral biofilm community provides a protective function to prevent invasion of foreign (pathogenic) bacteria [14]. Unfortunately, some of the bacterial species commonly found in the human oral biofilm consortium have the ability to cause diseases like tooth decay (caries). Under healthy conditions, these species would not cause any harm. Disease development is the result of a disturbed biofilm homeostasis leading to an overgrowth of conditional pathogenic bacteria and a general reduction of the species composition normally found in healthy supragingival plaque [15, 16]. Interestingly, clinical evidence emerges that some of the H2O2 producing oral streptococci seem to be reduced in their abundance in subjects having oral diseases like caries or periodontal disease [17–19].

The available in vivo and in vitro studies point to H2O2 as an important metabolic product generated in the early cycles of oral biofilm formation. In the following sections, specific examples important in biofilm development and in the adaptation to the oral biofilm environment are discussed.

2. Sources of H2O2

H2O2 in the oral cavity originates from bacteria and from the host [20]. At the present time, it is not clear how both sources influence each other and if at all the production of H2O2 by the host directly impacts the biofilm and vice versa. H2O2 has not been detected directly in saliva [21, 22]. The transient concentration has been calculated to be around 10 μM based on known concentrations of thiocyanate and hypothiocyanite in saliva [22]. One potential reason is the presence of a salivary scavenging system for H2O2 to protect the host from H2O2 toxicity [23, 24]. Two host-derived peroxidases are present in the human oral cavity, salivary peroxidase, and myeloperoxidase [23]. Both are able to use H2O2 as an oxidant and thiocyanate as a substrate to produce hypothiocyanite [23]. Interestingly, hypothiocyanite is not only a detoxification product, but also a general antimicrobial substance, and the combination of H2O2, hypothiocyanite, and salivary peroxidase seems to be most potent in inhibiting bacterial metabolism [25, 26]. Salivary peroxidase, a noninducible component of saliva originates in the parotid and submandibular glands [27]. Myeloperoxidase is an offensive component of polymorphonuclear leukocytes [28], which are present in saliva with elevated levels during inflammatory diseases like periodontal disease [29].

2.1. Sources of H2O2 in the Oral Biofilm

Oral streptococci have long been known to produce H2O2, mainly due to their ability to inhibit various other species in in vitro tests. Early reports already indicate that H2O2 production might be widely distributed among oral streptococci. Thompson and Shibuya tested 55 alpha-hemolytic oral streptococci and found that 48 were able to inhibit the growth of Corynebacterium diphtheria [30]. Tests with identified streptococcal species showed that Streptococcus oralis, Streptococcus mitis, Streptococcus sanguinis, and Streptococcus sobrinus all were able to produce significant amounts of H2O2 during growth in vitro, which can be detected in the supernatants of the growth medium [31]. These oral streptococci are commonly isolated and present in a relatively high abundance in the human oral biofilm [32]. Variations in H2O2 production among streptococci were shown to be growth medium and carbohydrate dependent [31], indicating environmental influences on regulatory mechanisms of H2O2 production.

The enzyme responsible for the production of H2O2 in S. sanguinis and S. gordonii was identified as pyruvate oxidase, encoded by gene spxB (also referred to as pox) [33–35]. The pyruvate oxidase is an oxidoreductase that catalyzes the conversion of pyruvate, inorganic phosphate (Pi), and molecular oxygen (O2) to H2O2, carbon dioxide (CO2), and the high-energy phosphoryl group donor acetyl phosphate in an aerobic environment. Genetic inactivation of the respective open reading frames encoding for putative pyruvate oxidase orthologs in S. sanguinis and S. gordonii confirmed the pyruvate oxidase as the enzyme responsible for significant H2O2 production [35]. The production of growth inhibiting amounts of H2O2 is not exclusive to the pyruvate oxidase in oral streptococci. Detailed genetic inactivation studies in Streptococcus oligofermentans showed that at least two other enzymes in addition to the pyruvate oxidase are able of producing growth-inhibiting amounts of H2O2 [36, 37]. The lactate oxidase, gene lctO (also referred to as lox), catalyzes the formation of pyruvate and H2O2 from L-lactate and oxygen and an L-amino acid oxidase generates H2O2 from amino acids and peptones. Dual species biofilm antagonism assays with S. oligofermentans and S. mutans demonstrated that the H2O2 produced by LctO activity is still able to antagonize S. mutans in an spxB background. The role of the L-amino acid oxidase in interspecies competition is not clear since its H2O2 producing activity is low, and only visible in a lctO/spxB double knockout mutant [36, 38]. Nonetheless, the L-amino acid oxidase seems to be important as suggested by a recent study, Boggs et al. showed that the L-amino acid oxidase gene aao from S. oligofermentans was probably acquired via horizontal gene transfer from a source closely related to S. sanguinis and S. gordonii, while evolutionary S. oligofermentans seems to be more closely related to S. oralis, S. mitis, and S. pneumoniae [39]. The authors speculate that the aao gene is important for S. oligofermentans to occupy a specific ecological niche in the oral biofilm [39]. The regulation of aao gene expression is not known, and the gene might be induced under specific conditions in vivo.

Using the available genome sequence data from the Human Oral Microbiome Database (http://www.homd.org/), the distribution of spxB and lctO among oral streptococci was determined using spxB and lctO from S. mitis B6 as a template. As shown in Table 1, several important oral streptococci encode open reading frames with a high homology to spxB and lctO. All species listed in Table 1 are commonly isolated from subjects suggesting a wide distribution of spxB and lctO in oral streptococci. Interestingly, spxB seemed to be more conserved among species when compared to lctO. The relatively wide distribution of spxB and lctO and the high degree of conservation suggest that both genes play an important role in the H2O2 production capabilities of the oral biofilm and might be considered as oral streptococcal community genes. Interestingly, inactivation of spxB in S. sanguinis diminishes competitive H2O2 production, suggesting that LctO plays no role in interspecies competition under the tested conditions in S. sanguinis [35].

Table 1.

Distribution and nucleotide identity of spxB and lctO among sequenced oral streptococcal isolates.

| Species | Strain | spxB identity (%) | lctO identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| B6 | 100 | 100 | |

| NCTC 12261 | 97 | 95 | |

| SK564 | 97 | 95 | |

| S. mitis | SK321 | 97 | 94 |

| SK597 | 96 | 94 | |

| F0392 | 96 | 93 | |

| SK95 | 96 | — | |

| ATCC 6249 | 96 | 90 | |

|

| |||

| SK36 | 94 | — | |

| S. sanguinis | SK49 | 95 | — |

| AATCC 49296 | 96 | 91 | |

|

| |||

| S. gordonii | CH1 | 96 | — |

|

| |||

| S. oralis | Uo5 | 96 | 91 |

| ATCC 35037 | 96 | 91 | |

|

| |||

| S. parasanguinis | SK236 | 95 | — |

|

| |||

| S. vestibularis | FO396 | 95 | — |

| ATCC 49124 | 95 | — | |

|

| |||

| S. peroris | ATCC 700780 | 95 | 90 |

| S. cristatus | ATCC 51100 | — | 87 |

| S. oligofermentans | AS 1.3089 | 95 | 88 |

2.2. Sources of H2O2 from the Host

H2O2 originates from several sources in the human body. Mitochondria are well-known producers of reactive oxygen species (ROS) as a byproduct of respiration [40]. Effective intracellular scavenging systems are in place to avoid ROS inflicted damage [41] and the H2O2 might not leave the oral mucosa in sufficient amounts to play a role in oral microbial biofilm ecology. A regulated production of ROS is observed as part of the oxidative burst from phagocytic cells [42]. The ROS production is directed towards the outsides of the phagocytic cell to defend the host from microbial pathogens and might therefore freely diffuse to nearby locations. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes seem to be the predominant phagocytic cells in saliva originating from the gingival crevice fluid and are constantly replenished [29]. However, one study with healthy individuals observed a high intraindividual day-to-day variability of salivary polymorphonuclear leukocyte content [43], making it difficult to judge how much H2O2 is being released as a consequence of phagocytic cell activity.

A more constant source of H2O2 supplied into saliva could originate from salivary gland cells expressing the dual oxidase 2 gene (Duox2) as shown by Geiszt et al. [44]. The same study also suggests that that ROS production occurs in the last step of saliva formation for direct delivery of ROS into the oral cavity [42, 44] and could therefore be the major source for salivary H2O2 originating from the host.

3. Hydrogen Peroxide in Oral Bacterial Ecology

3.1. Where Does It Matter: The Importance of Bacterial Proximity

The fact that H2O2 was never detected in saliva so far and the existence of a major scavenging system comprised of salivary peroxidases raise an important question: how likely does H2O2 affect oral bacterial ecology or aid in biofilm community adaptation? This question might be addressed by the fact that a bacterial biofilm comprises its own microcosm with intrinsic biofilm H2O2 production and most likely has a localized effect due to diffusion restrictions. By measuring the H2O2 concentration produced by single species, S. gordonii biofilms, Liu et al. were able to show that a steady state level of 1.4 mM H2O2 was produced at a distance of 100 μm above the biofilm surface [45]. Only 0.4 mM H2O2 is produced when measured 200 μm above the biofilm. This localized production of 1.4 mM is a concentration able to inhibit H2O2 susceptible bacteria, which have to be in close proximity. Remarkably, the same study also measured higher concentrations of H2O2 close to the surface of the biofilm as compared to planktonic grown cells [45]. This is in contrast to an earlier study by Nguyen et al. showing that S. sanguinis and S. gordonii had lower H2O2 production rates in biofilms when compared to planktonic cells [46]. This discrepancy might be partially explainable by the advanced method used in the study by Liu et al., allowing realtime detection with an H2O2 specific probe measuring directly above the biofilm surface [45]. Also, the study by Nguyen et al. used a higher concentration of glucose in the growth media, which might have repressed the H2O2 production rate [46] (see below: regulatory studies on H2O2 production). The difference in H2O2 concentration as a function of biofilm surface distance supports the suggestion that H2O2 producing species most likely have an effect on close neighboring species. When the cells dislodge and enter a planktonic state, H2O2 production becomes irrelevant. Taking into account that the oral biofilm is a diffusion barrier for larger proteins and molecules [47], the intrinsic H2O2 production of biofilm would also be more protected against the action of salivary lactoperoxidases, which might not penetrate preformed biofilms [48].

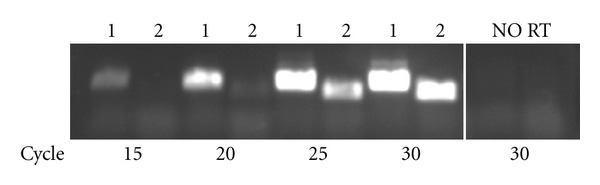

Detection of actual spxB expression in the human oral biofilm would support the importance of spxB-dependent H2O2 production. If spxB plays a vital role in oral biofilm ecology, one would expect that cells residing in the human oral biofilm express the spxB gene. Using freshly isolated plaque samples from a subject with no active caries, spxB specific cDNA was synthesized from RNA isolated from human oral biofilm bacteria and spxB expression confirmed (Figure 1; unpublished results). This observation not only shows for the first time the expression of an oral biofilm relevant gene in vivo but also strongly supports spxB relevance in the human dental plaque and suggests that spxB plays a role in biofilm specific processes.

Figure 1.

Expression of spxB in freshly isolated human plaque. To detect the expression of spxB among streptococcal species in the oral biofilm, plaque samples were collected from a healthy subject without active caries. Bacterial RNA was isolated and cDNA synthesized after standard protocols [59]. The spxB gene was PCR amplified from the synthesized cDNA with primers described by us earlier specific for spxB and 16S rRNA [59]. Samples were removed during the PCR run after 15, 20, 25, and 30 PCR cycles and loaded on an agarose gel for visualization. 1 = 16S rRNA; 2 = spxB; no RT = control for chromosomal DNA contamination.

3.2. Adaptation to a Competitive Environment-Genetic Exchange

Adaptation to the constantly changing oral environment requires some kind of genetic flexibility. This can be achieved by specific gene expression regulation and the adjustment of the transcriptome to sudden perturbations in the environment or by the acquisition of new genetic traits to cope with long-term environmental changes. Oral streptococci are known for their natural ability to take up extracellular DNA, a physiological state called competence [49]. Bacterial competence has long been recognized as the ability to take up DNA, but recent studies show that competence is part of a larger stress response, which enables competent bacteria to cope with a stressful environment [50]. Competent oral streptococci are able to take up homologous and heterologous DNA [51–53]. This increases the available DNA pool and allows for acquisition of new genetic traits from other species. Expression of newly acquired genetic traits depends on the homologous recombination of the incorporated DNA into the host chromosome [54, 55]. The mechanisms and genetic regulation of natural competence leading to the uptake and integration of DNA via homologous recombination are documented in numerous studies, and the basic blueprint of competence seems to be similar among oral streptococci [49, 56]. What is less known is how the biofilm community generates the extracellular DNA for DNA uptake by competent bacteria. A general mechanism of bacteria to produce extracellular DNA is an autolytic event leading to bacterial disintegration. Recent studies show that autolysis is a regulated process.

The release of DNA into the environment by S. gordonii and S. sanguinis is closely associated with the production of H2O2 [35]. The wild type organisms release high molecular weight DNA during aerobic growth, which was shown to be of chromosomal origin [57]. A deletion of the pyruvate oxidase gene affected this release process dramatically [57]. In addition, a significant reduced concentration of extracellular DNA was detected under oxygen limited growth conditions [58], correlating with a reduced expression of spxB and a lower amount of SpxB [59, 60]. Further studies showed that H2O2 is the only requirement to induce the DNA release process. Addition of H2O2 to anaerobically grown cells does induces DNA release. Although mechanistic studies are still in progress and the release process is not fully understood, our group has demonstrated a correlation between H2O2 induced DNA damage and extracellular DNA generation. Treatment with DNA damaging agents like UV light and mitomycin C also triggered the release of DNA under anaerobic conditions [58].

Initial evidence of an autolytic activity involved in the DNA release process comes from Robert A. Burne's group, showing that the major autolysin AtlS is involved in DNA release [61]. A deletion of AtlS in S. gordonii prevented autolysis under aerobic conditions, and as a consequence, a decreased production of extracellular DNA was observed [61]. Their observation, however, is in contrast to an observation by our group, showing that under anaerobic conditions, extracellular DNA release can be induced by H2O2 addition without any obvious bacterial cell lysis [58]. A possible explanation for these observations is that streptococci may have several mechanisms to trigger lysis responding to different internal and/or external stimuli. Autolysis may also not necessarily mean complete lysis of the bacterial cell or might only affect a small portion of the population. A recent report showed that S. gordonii expresses a murein hydrolase, LytF, involved in competence dependent bacterial lysis [62]. In fact, lytF is only expressed during competence because its expression is under the control of the competence stimulating peptide CSP, a small secreted peptide which accumulates in the environment after reaching a critical threshold concentration initiating the competence signaling cascade (see [50] for a detailed overview of competence in bacteria). DNA transfers experiments relying on LytF dependent cell lysis, and subsequent DNA uptake by S. gordonii showed that most cells are protected from the muralytic activity of LytF [62]. This is in agreement with our observation of a lysis resistant population [57, 58]. A close association, however, of H2O2 induced release of DNA and competence development is evident since cells grown under H2O2 producing conditions are also induced for competence development [58]. Interestingly, competence development in S. pneumoniae can be initiated by mitomycin C induced DNA damage, which also leads to the release of DNA [63]. This is reminiscent of our observation that DNA damaging agents induce DNA release [58], which is associated with the ecological advantage of H2O2 induced DNA release and the adaptation of oral streptococci to stress. S. gordonii and probably other H2O2-producing oral streptococci release DNA into the environment as a consequence of DNA damage. This pool of released DNA likely contains mutations in various genes because of the DNA damage. If such mutated DNA is taken up and integrated into the chromosome, the transformation event would lead to a bacterium able to grow and outcompete bacteria without the respective mutation under selective conditions. Even nonmutated extracellular DNA or genes would be useful as a template for the repair of stress-induced DNA damage [58]. The extracellular DNA is precisely produced at a time when it is biologically meaningful, under aerobic conditions during initial biofilm formation with its fierce interspecies competition and environmental stress, hence, when the cells are most competent for DNA transformation. Finally, H2O2 can also cause the release of DNA from streptococci not producing H2O2, but the mechanism for this is not known (unpublished results).

3.3. The Other Role of Extracellular DNA

Besides providing genetic information for transformation of competent oral streptococci, the DNA released as a consequence of H2O2-production might aid in initial biofilm development [64]. Although not directly shown for H2O2 producing oral streptococci, studies with S. mutans demonstrate the importance of extracellular DNA in initial adhesion. Das et al. showed that adhesion kinetics in the presence and absence of naturally occurring extracellular DNA were different. S. mutans cells adhered better and in greater numbers to the provided test surface when extracellular DNA was present [65, 66].

Initial biofilm formation involves the adhesion of pioneer colonizers to the tooth surface [3]. Another important event in early biofilm formation is bacteria-bacteria aggregation: (1) aggregation of bacteria before the actual attachment event in saliva increases the cluster size of bacteria able to adhere; (2) bacterial aggregation will also aid in the recruitment of other bacteria into the developing biofilm. Although aggregation of bacteria is well described with the identification of several surface proteins involved in the process [3], the role of extracellular DNA in oral bacterial aggregation is not well investigated. Studies with fresh water bacteria show that the released DNA functions in a netlike manner able to trap bacteria [67]. Initial evidence shows that extracellular DNA plays a role in the intraspecies aggregation of S. sanguinis. When grown as a planktonic culture, addition of extracellular DNA degrading DNase inhibits partially the aggregation [57]. Further studies are required to fully understand the role of extracellular DNA in multispecies biofilm formation and bacterial aggregation.

3.4. Biofilm Community Development

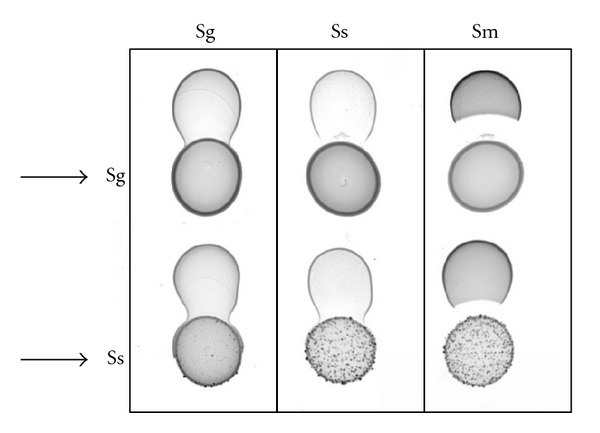

Earlier clinical studies have demonstrated the inverse relationship between S. sanguinis and cariogenic S. mutans [17, 19]. A recent study showed that S. oligofermentans is also frequently isolated from healthy human subjects [68]. The clinical evidence suggests that the initial colonization by H2O2-producing bacteria has a beneficial aspect for the human host with regard to caries development, possibly through the influential role of H2O2 on biofilm community development. Detailed in vitro experiments and relevant biofilm studies confirmed that S. sanguinis, S. gordonii, and S. oligofermentans produce H2O2 to inhibit S. mutans [8, 35, 37]. Although, the produced H2O2 has a slight self-inhibitory effect on the producing species in batch cultures, no obvious inhibition occurs when H2O2 producers are tested against each other in an antagonistic plate diffusion assay (Figure 2). As a consequence, community development favors integration of species that are compatible with the production of H2O2. Jakubovics et al. showed an interesting relationship between S. gordonii and Actinomyces naeslundii. Although A. naeslundii is severely inhibited in the aforementioned antagonistic plate diffusion assay, coaggregation cultures showed that both species could grow together in close proximity [69, 70]. S. gordonii is, however, the dominant species in this consortium, leading to a ratio of about 9 to 1. S. gordonii might benefit from this relationship by the fact that the H2O2 degrading catalase produced by A. naeslundii can reduce oxidative damage to S. gordonii proteins inflicted by its own H2O2 [70]. The low ratio of A. naeslundii to S. gordonii would still allow for sufficient inhibition of H2O2 susceptible species, but a clear ecological niche is necessary to support growth of both species, which could lead to the formation of more stable plaque communities. Another common oral isolate found in close association with S. gordonii is Veillonella ssp. [71]. Both species interact at the physiologic and metabolic level as shown by several studies [72–74]. Some strains of Veillonella also produce catalase, indicating that a similar effect as described for A. naeslundii might exist in the relationship between S. gordonii and Veillonella ssp. The biological relevance of the interactions between Streptococci, Veillonella, and Actinomyces has recently been demonstrated in vivo by confirming the spatial association of the three species in human plaque samples [2]. Further studies are required to determine the exact role of catalase production in the dual species relationship between H2O2-producing streptococci and catalase-expressing species.

Figure 2.

Oral streptococcal antagonism assay with S. sanguinis, S. gordonii, and S. mutans. The lower row in the plate dual-species antagonism assay were inoculated first (indicated by an arrow) and allowed to grow for 16 h. Subsequently, the to be tested species was inoculated in close proximity. Diffusible H2O2 produced by S. sanguinis (Ss) and S. gordonii (Sg) during growth caused inhibition of S. mutans (Sm), while no obvious growth inhibition was observed when S. sanguinis or S. gordonii was tested against themselves or against each other.

The production of H2O2 seems to select for a close association with compatible bacteria during biofilm community development. Therefore, H2O2 might shape the colonization pattern during initial biofilm formation and provide an ecological advantage for the producer and the accompanying H2O2 resistant species.

4. Regulatory Studies on H2O2 Production

S. gordonii and S. sanguinis —

A detailed analysis of environmental influences on S. gordonii's H2O2 production showed two important behaviors. (1) During growth under limited glucose and sucrose availability, S. gordonii produces only H2O2, while H2O2 and L-lactic acid are produced in equal amounts when concentrations of carbohydrates were higher than 0.1 mM. Since lower carbohydrate availability means increased competition among the biofilm microflora, a switch to only H2O2 production might increase the ecological competitiveness. (2) High glucose and sucrose concentrations inhibit the production of H2O2 [75]. This observation prompted us to further investigate the mechanism of H2O2 production control by determining spxB expression and SpxB abundance in S. sanguinis and S. gordonii under different environmental conditions. We could confirm the influence of carbohydrate concentration on spxB expression and abundance showing glucose repression in S. gordonii [59]. The carbohydrate dependent repression of spxB expression was also confirmed for galactose, maltose, and lactose, while sucrose and fructose seemed to have no effect in our strain [59]. This indicates that strain variability among S. gordonii might exist in the regulation of spxB expression. A detailed analysis of the promoter region of spxB from S. gordonii showed the existence of two putative binding sites for the catabolite control protein A (CcpA). CcpA is the main regulator of carbon catabolite repression in Gram-positive bacteria [76]. Mutational analysis of the promoter sequence confirmed the role of the CcpA binding sites and purified CcpA was able to bind to the respective regions in in vitro electromobility shift assays [59]. Surprisingly, the spxB expression in S. sanguinis is not influenced by carbohydrate availability, despite a high degree of promoter homology between both species and the presence of respective CcpA binding sites. However, a deletion of CcpA in S. sanguinis increased expression of spxB several folds [77]. This suggests that S. sanguinis constantly represses the expression of spxB or only lifts the repression due to a yet unknown environmental signal. One reason for this alternative spxB expression control could be S. sanguinis increased susceptibility to H2O2 when compared to S. gordonii (unpublished results). By keeping the production of H2O2 low, S. sanguinis might prevent self-damage of cellular components like surface adhesins, making it less competitive in the oral environment. The observation that monospecies biofilms of a S. sanguinis CcpA mutant had a higher proportion of dead cells when compared to the wild type further supports this hypothesis [77].

Both species do not produce competitive H2O2 under anaerobic growth conditions. Accordingly, spxB expression and SpxB abundance is greatly reduced under anaerobic growth conditions, but the protein is still detectable [59, 60]. This finding suggests that both streptococci keep a low level of SpxB present to remain competitive once they encounter aerobic conditions. The mechanisms of oxygen-dependent spxB expression control are not known at this time.

The spxB expression control involves additional regulators and proteins. Most notable is the identification of an SpxR homolog in S. sanguinis [78]. SpxR was originally identified in S. pneumoniae and it was hypothesized that SpxR in S. pneumoniae regulates spxB transcription in response to the energy and metabolic state of the cell [79]. Although not confirmed experimentally, this regulatory function might well be active in S. sanguinis, since no carbohydrate-dependent regulation was detected. Future research might address this question and identify what actual signal is involved in spxB regulation in S. sanguinis.

S. oligofermentans —

S. oligofermentans developed an interesting mechanism to produce antagonistic H2O2 and maximize its competitiveness. SpxB produces the majority of H2O2 during active growth [36] leading to the generation of an extra ATP through the spxB pathway. This ATP provides a metabolic growth advantage in addition to the ecological advantage of H2O2 production. The lctO-dependent H2O2 generation on the other hand is more prominent in the early stationary phase, due to an increased availability of lactate [36]. Several other oral streptococci encode genes for both H2O2 forming enzymes suggesting a similar role in H2O2 production. This dual SpxB/LctO presence indicates that even under starving conditions, oral streptococci might still produce competitive amounts of H2O2 to shape biofilm development towards a health compatible composition.

5. H2O2 in Oral Bacterial-Host Interactions

Oral streptococcal interactions occur in the mouth and therefore in close proximity to human host cells and the mucosal surface. Interactions with human innate immunity components are inevitable. Marvin Whiteley's group showed that the production of H2O2 has an unexpected effect on the recognition of pathogenic species by the immune response [80]. Using the recognized periodontal pathogen Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and S. gordonii as model organisms to study a combined effect on the host innate immune response, they described an interesting relationship between both species. Not only is A. actinomycetemcomitans able to effectively use the lactic acid produced by S. gordonii for growth [81] but it also responded to H2O2 as a signal to induce the expression of an immune evasion gene, apiA. This gene encodes an outer membrane protein able to bind factor H, conferring protection against killing by the alternative complement component of the innate immunity. In addition, the katA gene encoding cytoplasmic catalase is also induced, conferring resistance to the destructive action of H2O2 on A. actinomycetemcomitans cellular components [80].

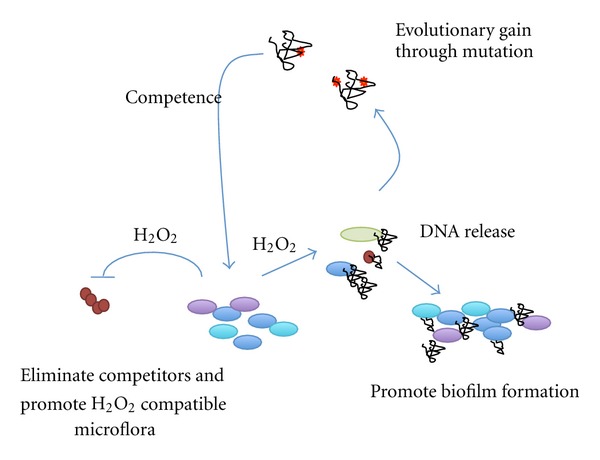

This observation demonstrates that biofilm community development is capable of remarkable evolutionary adaptations and that H2O2 plays a prominent role in the process of oral biofilm development (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Overview of the effects of H2O2 production on oral biofilm development. Initially, the antagonistic effect of streptococcal H2O2 production was described. As a consequence, competitors are eliminated, and the integration of H2O2 compatible species into the developing biofilm is promoted. H2O2 production also causes the release of DNA into the environment. The extracellular DNA promotes biofilm formation and cell-cell aggregation. In addition, H2O2 causes DNA damage, which in turn could lead to beneficial mutations in competent oral streptococci uptake of extracellular DNA. Extracellular DNA could therefore support adaptational processes to changing environmental conditions and promote evolution of oral biofilm development.

6. Concluding Remarks

One of the most important problems in current oral microbial research is to confirm biological relevance of in vitro experimental results. Accepted animal models to simulate oral biofilm ecology are generally rodent models. Although these models increase complexity, the transplanted human oral flora faces a rodent oral microbial consortium and a distinct oral environment. It therefore competes with species and conditions not encountered under normal conditions. It is not known if this complexity affects competition studies. A recent rodent study actually questions the validity of the importance of H2O2 production in S. gordonii competitiveness. Performing coinoculation studies in rats, Tanzer et al. showed that S. mutans is always able to outcompete S. gordonii under all experimental conditions [82]. Unfortunately, it was not determined whether the S. gordonii strain in their study produced competitive amounts of H2O2 or if the spxB gene was expressed in the rat oral biofilm. It is also unclear if the respective S. mutans strain was H2O2 susceptible. It is therefore important that animal studies about ecological questions actually demonstrate that the respective competitive gene set(s) are expressed under animal test conditions. It is also important to verify the expression of the gene(s) of interest in the human oral biofilm. Our initial data for spxB gene expression in the human oral biofilm are promising and warrant further research regarding the ecological role of H2O2 production in human oral biofilm.

Acknowledgments

J. Kreth was supported by NIH/NIDCR Grant R00DE018400. The authors thank Dr. J. Ferretti (Department of Microbiology & Immunology, University of Oklahoma HSC) for helpful comments.

References

- 1.Kolenbrander PE, Palmer RJ, Jr., Rickard AH, Jakubovics NS, Chalmers NI, Diaz PI. Bacterial interactions and successions during plaque development. Periodontology 2000. 2006;42(1):47–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valm AM, Mark Welch JL, Rieken CW, et al. Systems-level analysis of microbial community organization through combinatorial labeling and spectral imaging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(10):4152–4157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101134108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nobbs AH, Lamont RJ, Jenkinson HF. Streptococcus adherence and colonization. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2009;73(3):407–450. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00014-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolenbrander PE, Egland PG, Diaz PI, Palmer RJ., Jr. Genome-genome interactions: bacterial communities in initial dental plaque. Trends in Microbiology. 2005;13(1):11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kolenbrander PE, Palmer RJ, Jr., Periasamy S, Jakubovics NS. Oral multispecies biofilm development and the key role of cell-cell distance. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2010;8(7):471–480. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diaz PI, Chalmers NI, Rickard AH, et al. Molecular characterization of subject-specific oral microflora during initial colonization of enamel. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2006;72(4):2837–2848. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2837-2848.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosan B, Lamont RJ. Dental plaque formation. Microbes and Infection. 2000;2(13):1599–1607. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)01316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreth J, Merritt J, Shi W, Qi F. Competition and coexistence between Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguinis in the dental biofilm. Journal of Bacteriology. 2005;187(21):7193–7203. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.21.7193-7203.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryan CS, Kleinberg I. Bacteria in human mouths involved in the production and utilization of hydrogen peroxide. Archives of Oral Biology. 1995;40(8):753–763. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(95)00029-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradshaw DJ, Marsh PD, Keith Watson G, Allison C. Role of Fusobacterium nucleatum and coaggregation in anaerobe survival in planktonic and biofilm oral microbial communities during aeration. Infection and Immunity. 1998;66(10):4729–4732. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4729-4732.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stewart PS, Franklin MJ. Physiological heterogeneity in biofilms. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2008;6(3):199–210. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson M. Microbial Inhabitants of Humans. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2005. The oral cavity and its Indigious microbiota; pp. 318–372. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marquis RE. Oxygen metabolism, oxidative stress and acid-base physiology of dental plaque biofilms. Journal of Industrial Microbiology. 1995;15(3):198–207. doi: 10.1007/BF01569826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marsh PD. Dental plaque as a biofilm: the significance of pH in health and caries. Compendium of Continuing Education in Dentistry. 2009;30:76–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kleinberg I. Controversy: a mixed-bacteria ecological approach to understanding the role of the oral bacteria in dental caries causation: an alternative to Streptococcus mutans and the specific-plaque hypothesis. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology and Medicine. 2002;13(2):108–125. doi: 10.1177/154411130201300202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takahashi N, Nyvad B. The role of bacteria in the caries process: ecological perspectives. Journal of Dental Research. 2011;90(3):294–303. doi: 10.1177/0022034510379602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Becker MR, Paster BJ, Leys EJ, et al. Molecular analysis of bacterial species associated with childhood caries. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2002;40(3):1001–1009. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.3.1001-1009.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hillman JD, Socransky SS, Shivers M. The relationships between streptococcal species and periodontopathic bacteria in human dental plaque. Archives of Oral Biology. 1985;30(11-12):791–795. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(85)90133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nyvad B, Kilian M. Comparison of the initial streptococcal microflora on dental enamel in caries-active and in caries-inactive individuals. Caries Research. 1990;24(4):267–272. doi: 10.1159/000261281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carlsson J. Salivary peroxidase: an important part of our defense against oxygen toxicity. Journal of Oral Pathology. 1987;16(8):412–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1987.tb02077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ihalin R, Loimaranta V, Lenander-Lumikari M, Tenovuo J. The sensitivity of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum to different (pseudo)halide-peroxidase combinations compared with mutans streptococci. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2001;50(1):42–48. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-50-1-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pruitt KM, Tenovuo J, Mansson-Rahemtulla B, Harrington P, Baldone DC. Is thiocyanate peroxidation at equilibrium in vivo? Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1986;870(3):385–391. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(86)90245-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ashby MT. Inorganic chemistry of defensive peroxidases in the human oral cavity. Journal of Dental Research. 2008;87(10):900–914. doi: 10.1177/154405910808701003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pruitt KM. The salivary peroxidase system: thermodynamic, kinetic and antibacterial properties. Journal of Oral Pathology. 1987;16(8):417–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1987.tb02078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas EL, Milligan TW, Joyner RE, Jefferson MM. Antibacterial activity of hydrogen peroxide and the lactoperoxidase- hydrogen peroxide-thiocyanate system against oral streptococci. Infection and Immunity. 1994;62(2):529–535. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.529-535.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welk A, Rudolph P, Kreth J, Schwahn C, Kramer A, Below H. Microbicidal efficacy of thiocyanate hydrogen peroxide after adding lactoperoxidase under saliva loading in the quantitative suspension test. Archives of Oral Biology. 2011;56:1576–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riva A, Puxeddu P, Del Fiacco M, Testa-Riva F. Ultrastructural localization of endogenous peroxidase in human parotid and submandibular glands. Journal of Anatomy. 1978;127(1):181–191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clifford DP, Repine JE. Hydrogen peroxide mediated killing of bacteria. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 1982;49(3):143–149. doi: 10.1007/BF00231175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ozmeric N. Advances in periodontal disease markers. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2004;343(1-2):1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson R, Shibuya M. The inhibitory action of saliva on the diphtheria bacillus; the antibiotic effect of salivary streptococci. Journal of Bacteriology. 1946;51:671–684. doi: 10.1128/jb.51.6.671-684.1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garcia-Mendoza A, Liebana J, Castillo AM, De La Higuera A, Piedrola G. Evaluation of the capacity of oral streptococci to produce hydrogen peroxide. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 1993;39(6):434–439. doi: 10.1099/00222615-39-6-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lucas VS, Beighton D, Roberts GJ. Composition of the oral streptococcal flora in healthy children. Journal of Dentistry. 2000;28(1):45–50. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(99)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carlsson J, Edlund MB. Pyruvate oxidase in Streptococcus sanguis under various growth conditions. Oral Microbiology and Immunology. 1987;2(1):10–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1987.tb00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carlsson J, Edlund MB, Lundmark SK. Characteristics of a hydrogen peroxide-forming pyruvate oxidase from Streptococcus sanguis . Oral Microbiology and Immunology. 1987;2(1):15–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1987.tb00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kreth J, Zhang Y, Herzberg MC. Streptococcal antagonism in oral biofilms: Streptococcus sanguinis and Streptococcus gordonii interference with Streptococcus mutans . Journal of Bacteriology. 2008;190(13):4632–4640. doi: 10.1128/JB.00276-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu L, Tong H, Dong X. Function of the pyruvate oxidase-lactate oxidase cascade in interspecies competition between Streptococcus oligofermentans and Streptococcus mutans . Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2012;78:2120–2127. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07539-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tong H, Chen W, Merritt J, Qi F, Shi W, Dong X. Streptococcus oligofermentans inhibits Streptococcus mutans through conversion of lactic acid into inhibitory H2O2: a possible counteroffensive strategy for interspecies competition. Molecular Microbiology. 2007;63(3):872–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tong H, Chen W, Shi W, Qi F, Dong X. SO-LAAO, a novel L-amino acid oxidase that enables Streptococcus oligofermentans to outcompete Streptococcus mutans by generating H2O2 from peptone. Journal of Bacteriology. 2008;190(13):4716–4721. doi: 10.1128/JB.00363-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boggs JM, South AH, Hughes AL. Phylogenetic analysis supports horizontal gene transfer of l-amino acid oxidase gene in Streptococcus oligofermentans . Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2012;12(5):1005–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lambert AJ, Brand MD. Reactive oxygen species production by mitochondria. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2009;554:165–181. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-521-3_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Starkov AA. The role of mitochondria in reactive oxygen species metabolism and signaling. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1147:37–52. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leto TL, Geiszt M. Role of Nox family NADPH oxidases in host defense. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2006;8(9-10):1549–1561. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vidovic A, Vidovic Juras D, Vucicevic Boras V, et al. Determination of leucocyte subsets in human saliva by flow cytometry. Archives of Oral Biology. 2012;57(5):577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geiszt M, Witta J, Baffi J, Lekstrom K, Leto TL. Dual oxidases represent novel hydrogen peroxide sources supporting mucosal surface host defense. The FASEB Journal. 2003;17(11):1502–1504. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1104fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu X, Ramsey MM, Chen X, Koley D, Whiteley M, Bard AJ. Real-time mapping of a hydrogen peroxide concentration profile across a polymicrobial bacterial biofilm using scanning electrochemical microscopy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(7):2668–2673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018391108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen PTM, Abranches J, Phan TN, Marquis RE. Repressed respiration of oral streptococci grown in biofilms. Current Microbiology. 2002;44(4):262–266. doi: 10.1007/s00284-001-0001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robinson C. Mass transfer of therapeutics through natural human plaque biofilms. A model for therapeutic delivery to pathological bacterial biofilms. Archives of Oral Biology. 2011;56:829–836. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thurnheer T, Gmür R, Shapiro S, Guggenheim B. Mass transport of macromolecules within an in vitro model of supragingival plaque. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2003;69(3):1702–1709. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.3.1702-1709.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cvitkovitch DG. Genetic competence and transformation in oral streptococci. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology and Medicine. 2001;12(3):217–243. doi: 10.1177/10454411010120030201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Claverys JP, Prudhomme M, Martin B. Induction of competence regulons as a general response to stress in gram-positive bacteria. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2006;60:451–475. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu Y, Burne RA. Multiple two-component systems modulate alkali generation in Streptococcus gordonii in response to environmental stresses. Journal of Bacteriology. 2009;191(23):7353–7362. doi: 10.1128/JB.01053-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu Y, Dong Y, Chen YYM, Burne RA. Environmental and growth phase regulation of the Streptococcus gordonii arginine deiminase genes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2008;74(16):5023–5030. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00556-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perry D, Kuramitsu HK. Genetic transformation of Streptococcus mutans . Infection and Immunity. 1981;32(3):1295–1297. doi: 10.1128/iai.32.3.1295-1297.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Claverys JP, Martin B, Polard P. The genetic transformation machinery: composition, localization, and mechanism. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2009;33(3):643–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnsborg O, Håvarstein LS. Regulation of natural genetic transformation and acquisition of transforming DNA in Streptococcus pneumoniae . FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2009;33(3):627–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cvitkovitch DG, Senadheera D. Quorum sensing and biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans . Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2008;631:178–188. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78885-2_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kreth J, Vu H, Zhang Y, Herzberg MC. Characterization of hydrogen peroxide-induced DNA release by Streptococcus sanguinis and Streptococcus gordonii . Journal of Bacteriology. 2009;191(20):6281–6291. doi: 10.1128/JB.00906-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Itzek A, Zheng L, Chen Z, Merritt J, Kreth J. Hydrogen peroxide-dependent DNA release and transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in Streptococcus gordonii . Journal of Bacteriology. 2011;193:6912–6922. doi: 10.1128/JB.05791-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zheng L, Itzek A, Chen Z, Kreth J. Environmental influences on competitive hydrogen peroxide production in Streptococcus gordonii . Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2011;77(13):4318–4328. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00309-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zheng LY, Itzek A, Chen ZY, Kreth J. Oxygen dependent pyruvate oxidase expression and production in Streptococcus sanguinis . International Journal of Oral Science. 2011;3(2):82–89. doi: 10.4248/IJOS11030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu Y, Burne RA. The major autolysin of Streptococcus gordonii is subject to complex regulation and modulates stress tolerance, biofilm formation, and extracellular-DNA release. Journal of Bacteriology. 2011;193(11):2826–2837. doi: 10.1128/JB.00056-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Berg KH, Ohnstad HS, Havarstein LS. LytF, a novel competence-regulated murein hydrolase in the genus Streptococcus. Journal of Bacteriology. 2012;194:627–635. doi: 10.1128/JB.06273-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Prudhomme M, Attaiech L, Sanchez G, Martin B, Claverys JP. Antibiotic stress induces genetic transformability in the human pathogen streptoccus pneumoniae. Science. 2006;313(5783):89–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1127912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Flemming HC, Wingender J. The biofilm matrix. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2010;8(9):623–633. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Das T, Sharma PK, Busscher HJ, Van Der Mei HC, Krom BP. Role of extracellular DNA in initial bacterial adhesion and surface aggregation. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2010;76(10):3405–3408. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03119-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Das T, Sharma PK, Krom BP, van der Mei HC, Busscher HJ. Role of eDNA on the adhesion forces between Streptococcus mutans and substratum surfaces: influence of ionic strength and substratum hydrophobicity. Langmuir. 2011;27:10113–10118. doi: 10.1021/la202013m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dominiak DM, Nielsen JL, Nielsen PH. Extracellular DNA is abundant and important for microcolony strength in mixed microbial biofilms. Environmental Microbiology. 2011;13(3):710–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang J, Tong HC, Dong XZ, Yue L, Gao XJ. A preliminary study of biological characteristics of Streptococcus oligofermentans in oral microecology. Caries Research. 2010;44(4):345–348. doi: 10.1159/000315277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jakubovics NS, Gill SR, Iobst SE, Vickerman MM, Kolenbrander PE. Regulation of gene expression in a mixed-genus community: stabilized arginine biosynthesis in streptococcus gordonii by coaggregation with Actinomyces naeslundii . Journal of Bacteriology. 2008;190(10):3646–3657. doi: 10.1128/JB.00088-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jakubovics NS, Gill SR, Vickerman MM, Kolenbrander PE. Role of hydrogen peroxide in competition and cooperation between Streptococcus gordonii and Actinomyces naeslundii . FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 2008;66(3):637–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00585.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Palmer RJ, Jr., Diaz PI, Kolenbrander PE. Rapid succession within the Veillonella population of a developing human oral biofilm in situ. Journal of Bacteriology. 2006;188(11):4117–4124. doi: 10.1128/JB.01958-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu J, Wu C, Huang IH, Merritt J, Qi F. Differential response of Streptococcus mutans towards friend and foe in mixed-species cultures. Microbiology. 2011;157:2433–2444. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.048314-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Luppens SBI, Kara D, Bandounas L, et al. Effect of Veillonella parvula on the antimicrobial resistance and gene expression of Streptococcus mutans grown in a dual-species biofilm. Oral Microbiology and Immunology. 2008;23(3):183–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2007.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Palmer C, Bik EM, Eisen MB, et al. Rapid quantitative profiling of complex microbial populations. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34(1, article e5) doi: 10.1093/nar/gnj007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Barnard JP, Stinson MW. Influence of environmental conditions on hydrogen peroxide formation by Streptococcus gordonii . Infection and Immunity. 1999;67(12):6558–6564. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6558-6564.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Görke B, Stülke J. Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria: many ways to make the most out of nutrients. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2008;6(8):613–624. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zheng L, Chen Z, Itzek A, Ashby M, Kreth J. Catabolite control protein a controls hydrogen peroxide production and cell death in Streptococcus sanguinis . Journal of Bacteriology. 2011;193(2):516–526. doi: 10.1128/JB.01131-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen L, Ge X, Dou Y, Wang X, Patel JR, Xu P. Identification of hydrogen peroxide productionrelated genes in Streptococcus sanguinis and their functional relationship with pyruvate oxidase. Microbiology. 2011;157(1):13–20. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.039669-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ramos-Montañez S, Tsui HCT, Wayne KJ, et al. Polymorphism and regulation of the spxB (pyruvate oxidase) virulence factor gene by a CBS-HotDog domain protein (SpxR) in serotype 2 Streptococcus pneumoniae . Molecular Microbiology. 2008;67(4):729–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ramsey MM, Whiteley M. Polymicrobial interactions stimulate resistance to host innate immunity through metabolite perception. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(5):1578–1583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809533106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brown SA, Whiteley M. A novel exclusion mechanism for carbon resource partitioning in Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans . Journal of Bacteriology. 2007;189(17):6407–6414. doi: 10.1128/JB.00554-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tanzer JM, Thompson A, Sharma K, Vickerman MM, Haase EM, Scannapieco FA. Streptococcus mutans Out-competes Streptococcus gordonii in vivo . Journal of Dental Research. 2012;91(5):513–519. doi: 10.1177/0022034512442894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]