Abstract

The plant cell wall is a complex network of different polysaccharides and glycoproteins, showing high diversity in nature. The essential components, tethering cell wall are under debate, as novel mutants challenge established models. The mutant ugd2,3 with a reduced supply of the important wall precursor UDP-glucuronic acid reveals the critical role of the pectic compound rhamnogalacturonanII for cell wall stability. This polymer seems to be more important for cell wall integrity than the previously favored xyloglucan.

Keywords: apiose, cell walls, pectins, rhamnogalacturonanII, UDP-glucose dehydrogenase

Plant cell walls are complex compositions of different carbohydrate polymers and cell wall (glyco)-proteins. The composition of cell walls varies between different plant species, though they fulfill similar functions, mainly shaping and maintaining the cell form. This raises the question, which cell wall polymer networks are possible, stable and functional. To address this issue plants were mutagenized to modify cell wall components as a stress test for the interaction network. Most cell wall mutants that have been described and characterized up to now have been derived from Arabidopsis. Surprisingly one can modify the composition of cell walls in some mutants quite drastically. Examples are mutants like mur41 with a low arabinose content (< 50% of wild type) or xxt1,2, which lack xyloglucan.2 The latter finding comes as a surprise as common textbook and scientific models consider xyloglucans as the main cellulose fibril cross-linking polysaccharide in dicots. The role of xyloglucans for cell wall cross-linking and growth has been demonstrated widely. Nevertheless the loss of xyloglucan, detectable with standard procedures like glucanase-based fingerprinting or immunolabelling, is tolerated in xxt1,2 mutants suggesting a compensatory mechanism of cell wall stabilization.3 An emerging candidate polymer is the pectin rhamnogalacturonanII (RGII). It has a repetitive structure with a short galacturonic acid backbone, which is substituted by four complex side chains A-D.4 The long side chains A and B have an apiose residue attached to the galacturonic acid backbone. Two RGII side chains (mostly from different molecules) can be crosslinked via a borate diester, which is an essential step in controlling cell wall porosity and stability.5 Plant nutritionists have observed boron defects 50 y ago and linked the plant defects to swollen cell walls with an increase in cell wall thickness as seen in transmission electron microscope pictures.6 The Arabidopsis cell wall mutant mur1-1 lacks the terminal fucose at the end of the A and B chain of RGII, likely leading to a conformational change hindering efficient RGII-borate diester formation.7 This inefficiency can be overcome by exogenous application of millimolar amounts of borate ions.

In a recent paper by Reboul et al.8 a novel type of RGII-mutant was described which cannot be rescued by high boron concentrations. The mutant has a defect in two (out of four) genes coding for the enzyme UDP-glucose dehydrogenase (UGD). This enzyme oxidizes UDP-glucose into UDP-glucuronic acid, the direct precursor of UDP-apiose and UDP-xylose in plants.9 The loss of ugd2,3 causes a reduction of RGII side chains by 60% without changing the structure of the side chains. In contrast, the xyloglucan network is similar in wild type and ugd2,3. Why does ugd2,3 show strong changes in apiose in RGII but only minor changes in xylose in xyloglucan?

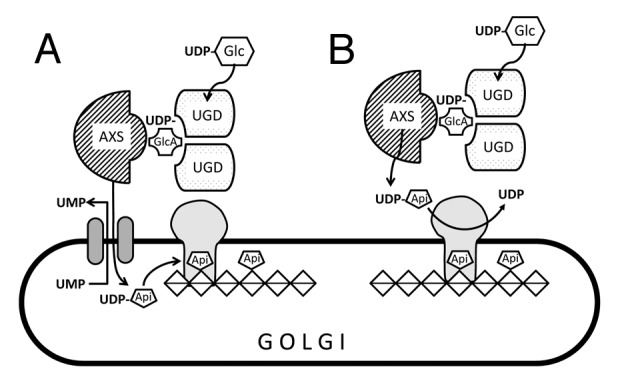

Recombinant enzymes for apiose-xylose synthase (AXS) and UDP-xylose synthase (UXS) have been characterized in the past. The Km for UDP-glucuronic acid of the cytoplasmatic AXS is about 7 µM,10 whereas the cytoplasmatic UXS1 displays a Km of about 500 µM.11 Therefore one would expect more drastic changes in the xyloglucan than in apiose containing polymers, if less UDP-glucuronic acid is available in ugd2,3. Alonso et al.12 determined the concentrations of this nucleotide sugar in Arabidopsis cell cultures. The value of 7.5 pMol·mg dry weight−1 may result in approximately 60–70 µM of UDP-glucuronic acid in the cytoplasm. If we assume a moderate reduction in ugd2,3 the concentration of UDP-glucuronic acid will still be several times higher than the Km of the enzyme AXS. The strong reduction of apiose in ugd2,3 is thus not explained by a moderate reduction in UDP-glucuronic acid. We therefore propose a model in Figure 1 in which the cytosolic enzymes UGD and AXS form a kind of complex for substrate channeling. In ugd2,3 this interaction may not be properly formed thus limiting the flux into UDP-apiose. As neither the apiosyltransferase for RGII biosynthesis nor the Golgi localized nucleotide sugar transporter for UDP-apiose is known, our model shows two alternative hypotheses. In Figure 1A a putative UDP-apiose producing enzyme complex would deliver UDP-apiose to a nucleotide sugar transporter. Alternatively, the apiosyltransferase might accept UDP-apiose from the outer side of the Golgi membrane though transferring the apiose onto a growing RGII-molecule inside the Golgi.

Figure 1. Model how UDP-glucose dehydrogenase (UGD) interacts with the apiose-xylose-synthase (AXS) at the Golgi membrane. The observed strong reduction in apiose in ugd2,3 mutants lacking two genes for UDP-glucose dehydrogenase may be explained by a complex of UGD with AXS occurring in the cytoplasm. The variants (A) and (B) differ in the further usage of UDP-apiose. In (A), the complex would deliver UDP-apiose to a hypothetical nucleotide transporter in exchange for UMP. The apiose is then transferred to a growing chain of α-1,4-galacturonic acid as part of the rhamnogalacturonanII polymer. In (B), UDP-apiose is used at the outer surface of the Golgi, where the transferase would attach the apiose to a galacturonic chain in the Golgi lumen.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/18894

References

- 1.Burget EG, Reiter WD. The mur4 mutant of arabidopsis is partially defective in the de novo synthesis of uridine diphospho L-arabinose. Plant Physiol. 1999;121:383–90. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.2.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavalier DM, Lerouxel O, Neumetzler L, Yamauchi K, Reinecke A, Freshour G, et al. Disrupting two Arabidopsis thaliana xylosyltransferase genes results in plants deficient in xyloglucan, a major primary cell wall component. Plant Cell. 2008;20:1519–37. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.059873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park YB, Cosgrove DJ. Changes in cell wall biomechanical properties in the xyloglucan-deficient xxt1/xxt2 mutant of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:465–75. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.189779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohnen D. Pectin structure and biosynthesis. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2008;11:266–77. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleischer A, Titel C, Ehwald R. The boron requirement and cell wall properties of growing and stationary suspension-cultured chenopodium album L. cells. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:1401–10. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.4.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee SG, Aronoff S. Investigations on the role of boron in plants III. Anatomical observations. Plant Physiol. 1966;41:1570–7. doi: 10.1104/pp.41.10.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Neill MA, Eberhard S, Albersheim P, Darvill AG. Requirement of borate cross-linking of cell wall rhamnogalacturonan II for Arabidopsis growth. Science. 2001;294:846–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1062319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reboul R, Geserick C, Pabst M, Frey B, Wittmann D, Lütz-Meindl U, et al. Down-regulation of UDP-glucuronic acid biosynthesis leads to swollen plant cell walls and severe developmental defects associated with changes in pectic polysaccharides. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:39982–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.255695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klinghammer M, Tenhaken R. Genome-wide analysis of the UDP-glucose dehydrogenase gene family in Arabidopsis, a key enzyme for matrix polysaccharides in cell walls. J Exp Bot. 2007;58:3609–21. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mølhøj M, Verma R, Reiter WD. The biosynthesis of the branched-chain sugar d-apiose in plants: functional cloning and characterization of a UDP-d-apiose/UDP-d-xylose synthase from Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2003;35:693–703. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harper AD, Bar-Peled M. Biosynthesis of UDP-xylose. Cloning and characterization of a novel Arabidopsis gene family, UXS, encoding soluble and putative membrane-bound UDP-glucuronic acid decarboxylase isoforms. Plant Physiol. 2002;130:2188–98. doi: 10.1104/pp.009654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alonso AP, Piasecki RJ, Wang Y, LaClair RW, Shachar-Hill Y. Quantifying the labeling and the levels of plant cell wall precursors using ion chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:915–24. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.155713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]