Abstract

Background and Purpose. Intravenous thrombolysis using tissue plasminogen activator is safe and probably effective in patients >80 years old. Nevertheless, its safety has not been specifically addressed for the oldest old patients (≥85 years old, OO). We assessed the safety and effectiveness of thrombolysis in this group of age. Methods. A prospective registry of patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis. Patients were divided in two groups (<85 years and the OO). Demographic data, stroke aetiology and baseline National Institute Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score were recorded. The primary outcome measures were the percentage of symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage (SICH) and functional outcome at 3 months (modified Rankin Scale, mRS). Results. A total of 1,505 patients were registered. 106 patients were OO [median 88, range 85–101]. Female sex, hypertension, elevated blood pressure at admission, cardioembolic strokes and higher basal NIHSS score were more frequent in the OO. SICH transformation rates were similar (3.1% versus 3.7%, P = 1.00). The probability of independence at 3 months (mRS 0–2) was lower in the OO (40.2% versus 58.7%, P = 0.001) but not after adjustment for confounding factors (adjusted OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.50 to 1.37; P = 0.455). Three-month mortality was higher in the OO (28.0% versus 11.5%, P < 0.001). Conclusion. Intravenous thrombolysis for stroke in OO patients did not increase the risk of SICH although mortality was higher in this group.

1. Introduction

Later years of life are marked by increased vulnerability to some events, such as stroke. The incidence of stroke increases exponentially with age. Different epidemiological studies have shown a rapid increase in the incidence of stroke, with that rate doubling each consecutive decade after 55 years of age and with stroke occurring in more than half of people over 75 years old [1]. People 85 years old or older, often known as the oldest old (OO) [2, 3], are the fastest growing segment of the older American population [4]. By 2050, it is estimated that there will be more than 55 million nonagenarians worldwide [5], and very old patients will likely constitute the majority of stroke victims [6–8]. The Oxford Vascular Study indicated a 12-fold increase in the incidence of stroke in the OO, compared with the younger population [9]. The OO also have higher mortality, morbidity, disability, and greater functional impairment compared with younger patients [10–12].

Intravenous thrombolytic treatment with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (IV-tPA) is the only medical therapy currently available for acute ischaemic stroke, reducing the risk of death or dependence [13–15]; however, the European Medicines Evaluation Agency has not approved thrombolysis for patients over 80 on the basis that there is no experience with this particular segment, as they have been excluded or underrepresented in major clinical trials. Only 42 patients (7%) over 80 years old were included in the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) trial [13, 16]. In a subgroup analysis of this trial, there was no correlation between symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhage (SICH) and age [13, 17]. More recently, several studies have demonstrated the safety of IV-tPA in patients over 80 years of age [18–25]. Nevertheless, it is not as well known for the OO because the cases covered in these series either only includes a small percentage from this particular group or the authors did not perform specific analyses [24, 26–28].

Herein, we present a review of our experience with IV-tPA in very old patients. We evaluate its safety and effectiveness in comparison with its use in younger patients.

2. Material and Methods

Study design: observational analysis of a multicentre stroke registry with prospective inclusion of consecutive acute ischemic stroke patients treated with IV-tPA at five stroke units (SU) at the Madrid Stroke Network, from January 2003 to December 2010 [29].

Treatment: patients who fulfilled criteria for intravenous thrombolysis received IV-tPA in a standard 0.9 mg/kg dose within three hours of stroke onset. Since the publication of the ECASS-III and data from the SITS registry, patients have been treated within the 4.5-hour time window [14, 30]. Patients or surrogates (in cases of patients lacking capacity due to severity of stroke or other reasons) signed an informed consent document prior to IV-tPA, which specifically included consent for the inclusion of clinical data in a database. This database was approved by Ramón y Cajal University Hospital Ethics Committee for Clinical Research.

3. Clinical Assessment

Stroke onset was defined as the last time the patient was known to be without neurological deficit. On admission, neurological examination and cranial computed tomography (CT) scan were performed. Stroke severity was assessed, using baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score, at 24 hours and at 7 days after treatment. NIHSS-certified neurologists performed all evaluations. Basal mRS was defined on mRS score before stroke (estimated from the information provided by family members living with the patient) [31]. Covariables included age, sex, stroke risk factors, and stroke aetiology, as well as the blood glucose level and the systolic arterial blood pressure (BP) on admission. Elevated BP was defined as a BP > 185/110 mm Hg. Previous antithrombotic treatments (antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants) were recorded. Effective anticoagulant treatment was considered as a contraindication for IV-tPA. The following intervals were recorded: stroke onset-to-door, stroke onset-to-treatment, and door-to-treatment. A posttreatment CT scan was performed on all patients after 24 hours (range, 22–36 hours) or earlier in the case of neurological deterioration. In addition, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) was used in selected cases. Cerebral haemorrhages were classified according to the Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study (SITS-MOST) [25] classification (HI1, HI2, PH1, PH2, PHr1, PHr2). Symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage (SICH) was defined as local or remote type 2 parenchymal haemorrhages combined with a neurological deterioration of 4 or more points from baseline on the NIHSS score, from the lowest NIHSS value between baseline and 24 hours, or leading to death [30]. Asymptomatic intracranial haemorrhage (AICH) was defined as the presence of a haemorrhage on the CT scan without neurological deterioration.

Functional outcome was rated using the modified Rankin scale (mRs) after 90 days, and functional outcomes were classified as follows: favourable (0-1), independent (0–2), moderate disability, severe disability or death (3–6), and case fatality (6). Causes of death were classified as follows: stroke, SICH, myocardial infarction, pulmonary thromboembolism, pneumonia, other vascular causes, and other causes.

4. Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) versus 17 (SPSS Inc., Somers, NY, USA). Descriptive analyses were completed using the median and percentiles (P25 and P75) for quantitative variables and the frequency and percentage for qualitative variables. Comparisons were made according to age (OO versus <85 years old) with univariate analyses using the Pearson's chi-square test and the Mann-Whitney U-test, as appropriate. Three logistic regression models were constructed to estimate the association between age ≥ 85 years and mortality, haemorrhagic transformation and mRs at 3 months, respectively, adjusting for other possible confounder variables (sex, basal NIHSS score, cardioembolic aetiology, prior antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy, stroke onset-to-treatment time, basal mRS and elevated BP in the acute phase of stroke). Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated. The existences of interactions between the possible confounder variables and age ≥ 85 years were also explored. After determining whether an interaction existed or not, the presence of confounders was also studied. A backward elimination strategy was used. Factors were considered to be confounding if the coefficient of the variable age ≥ 85 years was modified by more than 10% of its value after removing the suspect variable. All values were based on 2-tailed statistical analyses, with values of P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

5. Results

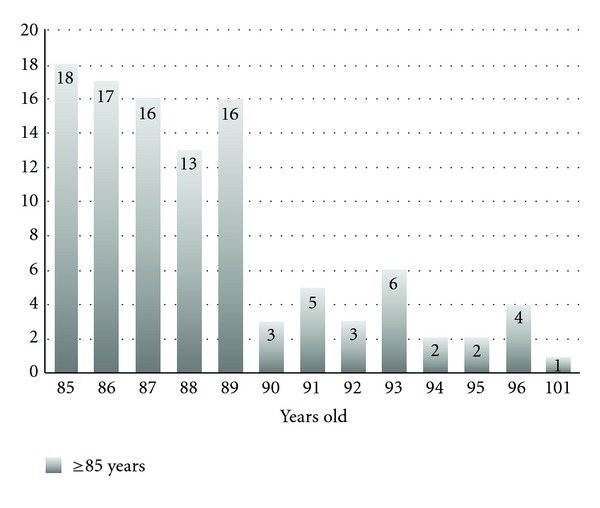

A total of 1,505 patients were treated with IV-tPA and included in the database. One hundred and six (7%) were OO (median 88; range 85–101) (Figure 1). Table 1 shows baseline and demographic data, stroke aetiology, and degree of neurological severity of both groups. The OO group had a significantly higher proportion of females (68.9% versus 45.1%, P < 0.001) and a higher incidence of arterial hypertension (78.6% versus 60.4%, P < 0.001), elevated BP on admission (26.7% versus 14.8%, P = 0.001), atrial fibrillation (30.1% versus 17.4%, P = 0.001), and prior antiplatelet therapy (33.0% versus 20.2%, P = 0.002). Patients in the OO group were also less likely to smoke (1% versus 23.3%, P < 0.001). Stroke severity was higher in the OO group (median baseline NIHSS score 16 versus 13, P = 0.001). The stroke onset-to-door time in the OO group was significantly longer (85 min versus 75 min, P = 0.049), but neither the door-to-treatment time nor the stroke-onset-to-treatment times differed between groups. Cardioembolic stroke was significantly more frequent in the OO group (61.7% versus 42.1%, P = 0.003).

Figure 1.

Distribution of patients according to age (Oldest Old group).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and aetiology.

| <85 years old | Oldest Old | Group comparison P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 1399 (93) | 106 (7) | |

| Age, y-o (median, range) | 71 (18–84) | 88 (85–101) | |

| Gender | |||

| Female, n (%) | 630 (45.1) | 73 (69.9) | < 0.001* |

| Risk factors | |||

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 837 (60.4) | 81 (78.6) | <0.001* |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 280 (20.2) | 14 (13.6) | 0.103 |

| Dyslipemia, n (%) | 485 (35.2) | 29 (28.2) | 0.149 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 322 (23.3) | 1 (1) | < 0.001* |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 241 (17.4) | 31 (30.1) | 0.001* |

| Prior antiplatelet therapy, n (%) | 280 (20.2) | 34 (33) | 0.002* |

| Prior anticoagulation therapy, n (%) | 57 (4.1) | 7 (6.8) | 0.149 |

| Elevated BP (>185/110 mg Hg) on admission n (%) | 200 (14.8) | 27 (26.7) | 0.001* |

| Blood glucose on admission (mmol/dL), median (IQR) | 119 (102–144) | 118 (10.5–151.5) | 0.415 |

| Baseline NIHSS, median (IQR) | 13 (8–18) | 16 (10–21) | < 0.001* |

| Time (min), median (IQR) | |||

| Stroke onset-to-door time | 75 (55–110) | 85 (64–115) | 0.049* |

| Door-to-treatment time | 58 (42–76) | 58 (45–74) | 0.808 |

| Stroke onset-to-treatment time | 144.5 (115–173.7) | 142.5 (120–186.2) | 0.265 |

| Aetiology, n (%) | |||

| Atherothrombotic | 325 (24.2) | 19 (20.2) | ns |

| Cardioembolic | 565 (42.1) | 58 (61.7) | 0.025* |

| Lacunar | 60 (4.5) | 1 (1.1) | ns |

| Other determined aetiology | 72 (5.4) | 0 | ns |

| Undetermined aetiology | 321 (23.9) | 16 (17) | ns |

NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; IQR: interquartile range; BP: blood pressure. Statistical significance *P < 0.005.

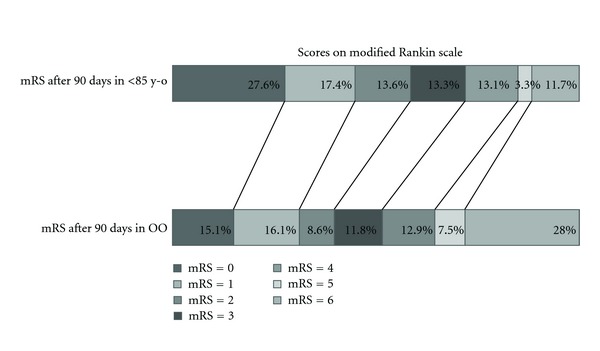

Postbasal functional outcome values, up to three months after stroke, were obtained for the vast majority of patients (1,413, 93.8%). Only 79 (5.65%) and 13 (12.26%) patients of each group were lost to follow up. Mortality was significantly higher in the OO group (28.0% versus 11.5%, P < 0.001). The cause of death differed between groups, being pneumonia the leading cause of death (48%) in the OO group. The number of patients with a favourable (31.2% versus 45%, P = 0.009) or an independent (40.2% versus 58.7%, P = 0.001) outcome was significantly smaller in the OO group (Figure 2). There were no differences in the proportion of SICH between the two groups (3.1% in the OO versus 3.7% in the group of <85 years old; p=1.000) or AICH (16% versus 16%, P = 0.083) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Scores on modified Rankin scale.

Table 2.

Clinical outcome and haemorrhagic complications.

| <85 y-o n = 1399 | Oldest Old n = 106 | Group comparison P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients lost to followup n (%) | 79 (5.65) | 13 (12.26) | |

| NIHSS score at 24 hours, median (IQR) | 6 (2–15) | 11 (4–19) | <0.001* |

| NIHSS score at day 7, median (IQR) | 3 (0–11) | 6 (1–16.5) | 0.005* |

| Long-term outcome parameters (day 90) | |||

| Favourable outcome (mRS 0-1), n (%) | 594 (45) | 29 (31.2) | 0.009* |

| Independent outcome (mRS 0–2), n (%) | 772 (58.7) | 37 (40.2) | 0.001* |

| Moderate disability, severe disability, or death (mRS 3–6), n (%) | 541 (41.1) | 55 (59.8) | 0.001* |

| Mortality n (%) | 155 (11.5) | 26 (28) | <0.001* |

| Causes of death | |||

| Ischaemic stroke, n (%) | 60 (42.3) | 9 (36) | ns |

| SICH, n (%) | 16 (11.3) | 1 (4) | ns |

| Myocardial Infarction, n (%) | 5 (3.5) | 1 (4) | ns |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 41 (28.9) | 12 (48) | ns |

| Pulmonary thromboembolism, n (%) | 1 (0.7) | 0 | ns |

| Other vascular causes, n (%) | 7 (4.9) | 2 (8) | ns |

| Hemorrhagic transformation | |||

| AICH, n (%) | 201 (16%) | 15 (16%) | 0.983 |

| SICH, n (%) | 48 (3.7) | 3 (3.1) | 1.000 |

NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; mRS: Modified Rankin Scale; IQR: interquartile range. SICH: symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage; AICH: Asymptomatic intracranial haemorrhage. Statistical significance *P < 0.005.

A multivariate analysis was used to compare the mortality, haemorrhagic transformation, and functional independence (mRs 0–2) at 3 months between the two groups, adjusting for other possible confounding factors. Elevated BP on admission, baseline NIHSS score, basal mRs, and prior antiplatelet therapy were identified as confounding factors by multiple regression analysis (see Table 3). After this adjustment, there were no differences in the proportion of haemorrhagic transformation in both groups (adjusted OR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.43 to 1.30; P = 0.296), and there was no statistically significant difference in functional independence in the OO group (adjusted OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.50 to 1.37; P = 0.455). Mortality remained higher among the OO group (adjusted OR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.18 to 3.55; P = 0.011).

Table 3.

Regression analysis.

| Univariate analysis | Adjusted analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI 95% | P | OR | CI 95% | P | |

| Mortality OO∗ | 2.98 | 1.84–4.82 | <0.001* | 2.04 | 1.18–3.55 | 0.0 11* |

| Haemorrhagic transformation OO† | 0.83 | 0.26–2.73 | 0.396 | 0.74 | 0.43–1.30 | 0.296 |

| mRs (day 90) OO† | 0.47 | 0.31–0.73 | 0.0 01* | 0.82 | 0.50–1.37 | 0.455 |

*Adjusted by baseline NIHSS and elevated BP on admission; †Adjusted by baseline NIHSS score, elevated BP on admission and sex. Statistical significance *P < 0.005.

6. Discussion

Some of the reasons clinical trials with IV-tPA excluded older patients included impaired rate of tPA clearance, increased rate of cardioembolic strokes, and the presence of amyloid angiopathy that could increase the rate of SICH [6, 32]. Mortality rates and the proportion of moderate or severe functional impairment after an acute ischaemic stroke are higher in the elderly [12, 33, 34]. In general, the series of patients older than 80 years treated with IV-tPA have had increased mortality, and the proportion of patients with good functional outcome was smaller in comparison with younger patients [6, 7, 18–21]. Furthermore, Sarikaya et al. [27] have suggested less favourable outcomes in nonagenarians as compared with octogenarians after IV-tPA. However, very recently, the Safe Implementation of Treatment in Stroke-International Stroke Thrombolysis Register (SITS-ISTR) has provided the largest amount of data on the safety and outcome in thrombolysis in patients >80 years of age. This group concluded that these patients had a similar rate of SICH, and the higher mortality and the poorer functional outcomes were consistent with the overall worse prognosis seen in the natural history of this age group; therefore, patients in this age group are appropriate candidates for thrombolysis [25]. Moreover, this group performed an adjusted controlled comparison of outcomes between stroke patients who underwent thrombolysis through the SITS-ISTR, with untreated stroke patients from neuroprotection trials held within the Virtual International Stroke Trials Archive (VISTA). Although increasing age is associated with a poorer outcome, the association between thrombolysis treatment and improved outcome is maintained in very old patients [25]. Mateen et al. [26] compared the outcomes of thrombolysis in octogenarians and nonagenarians and found that there were no significant differences in functional outcome or rate of SICH.

Our analysis of prospectively collected data indicates that a small cohort of very old patients were treated using thrombolysis (7% of all patients treated). One possible explanation is that our registry started in 2004, when information about IV-tPA in old patients was scarce. The majority (78.3%) of older patients were treated in the last two years of the registry. Alshekhlee et al. [23] also found very low rates of thrombolysis among very old patients and a trend of increasing IV-tPA use in this age segment over the recent years.

Our results show that a large proportion of OO patients treated with IV-tPA were functionally independent at 90 days (40.2%), although this figure was significantly higher in the group of patients <85 years (58.7%). Furthermore, the mortality rate was higher in the elderly group (28%). As we can see in our multivariable analysis, the worse functional recovery can be explained by confounding factors, whereas mortality was worse in the OO, despite adjustment. We feel that this fact is due the expected major fragility of this age group. Pneumonia was the most common cause of death in the OO group. The rate of SICH in both groups was similar. We did not find any significant differences in the times of management of the stroke inside the hospital, and only stroke-onset-to-door time was significantly longer when compared to the total group of the registry.

This study has several limitations. First, it reports the results of a small cohort of very old patients, and the cohort was compared with a more numerous cohort of patients < 85 years old. Second, the study is a post hoc analysis of a registry, and selection bias is an important limitation to the data set. The decision to administer IV-tPA was made by multiple different treating neurologists, and some factors, not limited to age and prior functional status, could bias treating very old patients with IV-tPA. Finally, the main limitation of the study is the lack of a concurrent untreated control group.

This study supports the use of thrombolytic treatment for very old patients, with safety results similar to younger patients. Although OO patients may have a higher mortality at three months, they still do better than those who do not receive IV-tPA.

As evidence of safety of thrombolysis in very old is increasing, more elderly patients are now treated with IV-tPA. However, reliable evidence on the risk-benefit balance of intravenous thrombolysis in this age group can only be evaluated using randomised controlled thrombolysis trials, such as the ongoing Third International Stroke Trial or the Thrombolysis in Elderly Stroke Patients [35, 36].

Conflict of Interests

There is no financial interest related to this paper. The authors confirm that there is no conflict of interests. This paper has not been previously published, nor is it under consideration for publication by any other journal.

Acknowledgments

This work is part of the Spanish collaborative research network RENEVAS (Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, RD06/0026/008, RD07/0026/2003). The authors thank all of their colleagues from the department of Neurology, medical and technical staff in the participating centers for their support, specially Guillermo Garcia Ribas and Florentino Nombela. They also thank Ana Royuela and Nieves Plana from Clinical Biostatistics unit, CIBERESP, Madrid.

References

- 1.Feigin VL, Lawes CMM, Bennett DA, Anderson CS. Stroke epidemiology: a review of population-based studies of incidence, prevalence, and case-fatality in the late 20th century. Lancet Neurology. 2003;2(1):43–53. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00266-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campion EW. The oldest old. New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;330(25):1819–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406233302509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Aging and life course. 2006, http://whqlibdoc.who.int/gender/2003/a85586.pdf.

- 4.Hobbs FB. The elderly population. US Census Bureau Population Profile of the United States, http://www.census.gov/population/www/pop-profile/elderpop.html.

- 5.International year of older persons: demographic of older persons. United Nations Department of Public Information, 1999, http://www.un.org/NewLinks/older/99/older.htm.

- 6.Tanne D, Gorman MJ, Bates VE, et al. Intravenous tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke in patients aged 80 years and older: the tPA stroke survey experience. Stroke. 2000;31(2):370–375. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.2.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olindo S, Cabre P, Deschamps R, et al. Acute stroke in the very elderly: epidemiological features, stroke subtypes, management, and outcome in Martinique, French West Indies. Stroke. 2003;34(7):1593–1597. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000077924.71088.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Carlo A, Launer LJ, Breteler MMB, et al. Frequency of stroke in Europe: a collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurology. 2000;54(11, supplement 5):S28–S33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothwell PM, Coull AJ, Giles MF, et al. Change in stroke incidence, mortality, case-fatality, severity, and risk factors in Oxfordshire, UK from 1981 to 2004 (Oxford Vascular Study) Lancet. 2004;363(9425):1925–1933. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Carlo A, Lamassa M, Pracucci G, et al. Stroke in the very old: clinical presentation and determinants of 3-month functional outcome: a European perspective. Stroke. 1999;30(11):2313–2319. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.11.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pohjasvaara T, Erkinjuntti T, Vataja R, Kaste M. Comparison of stroke features and disability in daily life in patients with ischemic stroke aged 55 to 70 and 71 to 85 years. Stroke. 1997;28(4):729–735. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.4.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Béjot Y, Rouaud O, Jacquin A, et al. Stroke in the very old: incidence, risk factors, clinical features, outcomes and access to resources—a 22-year population-based study. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2010;29(2):111–121. doi: 10.1159/000262306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marler JR. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;333(24):1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359(13):1317–1329. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lees KR, Bluhmki E, von Kummer R, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: an updated pooled analysis of ECASS, ATLANTIS, NINDS, and EPITHET trials. The Lancet. 2010;375(9727):1695–1703. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60491-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longstreth WT, Katz R, Tirschwell DL, Cushman M, Psaty BM. Intravenous tissue plasminogen activator and stroke in the elderly. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010;28(3):359–363. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hacke W, Donnan G, Fieschi C, et al. Association of outcome with early stroke treatment: pooled analysis of ATLANTIS, ECASS, and NINDS rt-PA stroke trials. Lancet. 2004;363(9411):768–774. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15692-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berrouschot J, Röther J, Glahn J, Kucinski T, Fiehler J, Thomalla G. Outcome and severe hemorrhagic complications of intravenous thrombolysis with tissue plasminogen activator in very old (≥80 years) stroke patients. Stroke. 2005;36(11):2421–2425. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000185696.73938.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pundik S, McWilliams-Dunnigan L, Blackham KL, et al. Older age does not increase risk of hemorrhagic complications after intravenous and/or intra-arterial thrombolysis for acute stroke. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2008;17(5):266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gómez-Choco M, Obach V, Urra X, et al. The response to IV rt-PA in very old stroke patients. European Journal of Neurology. 2008;15(3):253–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.02042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhatnagar P, Sinha D, Parker RA, Guyler P, O’Brien A. Intravenous thrombolysis in acute ischaemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis to aid decision making in patients over 80 years of age. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2011;82(7):712–717. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.223149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeevi N, Chhabra J, Silverman IE, Lee NS, McCullough LD. Acute stroke management in the elderly. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2007;23(4):304–308. doi: 10.1159/000098332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alshekhlee A, Mohammadi A, Mehta S, et al. Is thrombolysis safe in the elderly? Analysis of a national database. Stroke. 2010;41(10):2259–2264. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.588632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ford GA, Ahmed N, Azevedo E, et al. Intravenous alteplase for stroke in those older than 80 years old. Stroke. 2010;41(11):2568–2574. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.581884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mishra NK, Ahmed N, Andersen G, et al. Thrombolysis in very elderly people: controlled comparison of SITS International Stroke Thrombolysis Registry and Virtual International Stroke Trials Archive. BMJ. 2010;341, article c6046 doi: 10.1136/bmj.c6046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mateen FJ, Nasser M, Spencer BR, et al. Outcomes of intravenous tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke in patients aged 90 years or older. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2009;84(4):334–338. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60542-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarikaya H, Arnold M, Engelter ST, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis in nonagenarians with ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2011;42(7):1967–1970. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.601252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mateen FJ, Buchan AM, Hill MD. Outcomes of thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke in octogenarians versus nonagenarians. Stroke. 2010;41(8):1833–1835. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.586438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alonso De Leciñana-Cases M, Gil-Núñez A, Díez-Tejedor E. Relevance of stroke code, stroke unit and stroke networks in organization of acute stroke care—the Madrid acute stroke care program. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2009;27(supplement 1):140–147. doi: 10.1159/000200452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wahlgren N, Ahmed N, Dávalos A, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke in the Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study (SITS-MOST): an observational study. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):275–282. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonita R, Beaglehole R. Recovery of motor function after stroke. Stroke. 1988;19(12):1497–1500. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.12.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barber PA, Zhang J, Demchuk AM, Hill MD, Buchan AM. Why are stroke patients excluded from TPA therapy? An analysis of patient eligibility. Neurology. 2001;56(8):1015–1020. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.8.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heuschmann PU, Kolominsky-Rabas PL, Roether J, et al. Predictors of in-hospital mortality in patients with acute ischemic stroke treated with thrombolytic therapy. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292(15):1831–1838. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.15.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kammersgaard LP, Jørgensen HS, Reith J, Nakayama H, Pedersen PM, Olsen TS. Short- and long-term prognosis for every old stroke patients. The Copenhagen Stroke Study. Age and Ageing. 2004;33(2):149–154. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toni D, Lorenzano S. Intravenous thrombolysis with rt-PA in acute stroke patients aged ≥ 80 years. International Journal of Stroke. 2009;4(1):21–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sandercock P, Lindley R, Wardlaw J, et al. The third international stroke trial (IST-3) of thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Trials. 2008;9, article no. 37 doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-9-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]