Abstract

The colours of birds are diverse but limited relative to the colours they can perceive. This mismatch may be partially caused by the properties of their colour-production mechanisms. Aside from pigments, several classes of highly ordered nanostructures (thin films, amorphous three-dimensional arrays) can produce a range of colours. However, the variability of any single nanostructural class has rarely been explored. Dabbling ducks are a speciose clade with substantial interspecific variation in the iridescent coloration of their wing patches (specula). Here, we use electron microscopy, spectrophotometry, polarization and refractive index-matching experiments, and optical modelling to examine these colours. We show that, in all species examined, speculum colour is produced by a photonic heterostructure consisting of both a single thin-film of keratin and a two-dimensional hexagonal lattice of melanosomes in feather barbules. Although the range of possible variations of this heterostructure is theoretically broad, only relatively close-packed, energetically stable variants producing more saturated colours were observed, suggesting that ducks are either physically constrained to these configurations or are under selection for the colours that they produce. These data thus reveal a previously undescribed biophotonic structure and suggest that both physical variability and constraints within single nanostructural classes may help explain the broader patterns of colour across Aves.

Keywords: photonic crystal, Anatidae, iridescence, thin films, sexual selection, nanophotonics

1. Introduction

The display of colours for inter- and intraspecific communication has been a fundamental function of the metazoan integument since the evolution of vision in the Cambrian explosion [1]. Colours can allow an organism either to hide from potential predators or prey or to become more conspicuous for aposematic or sexual display [2–4]. The plumages of birds range from highly cryptic to highly conspicuous and indeed at the latter extreme have some of the most vivid colours found in nature. A recent study [5] showed that, while diverse, these colours are limited relative to what birds can perceive. This pattern of unoccupied regions in colour space may be explicable at least in part by the physical constraints stemming from the mechanisms by which those colours are produced. Further, to understand how complex structures like colourful plumage patches evolve, it is important to investigate not only the observed phenotypic variation but also the ability to produce new variants (i.e. variability, sensu [6]).

While selective light absorption by pigments like carotenoids and psittacofulvins can produce highly saturated colours [7], these appear to be limited to yellows and reds and are incapable of producing shorter wavelength hues (e.g. blues and violets). By contrast, structural colours resulting from coherent scattering of light by highly ordered nanostructures are capable of producing colours across most of the bird-visible spectrum [5]. For example, previously described nanostructures produce ultraviolet [8], blue [9], green [10], yellow [11] and red coloration [12]. This diversity in colour is facilitated both by the diversity of morphological classes producing structural colour (i.e. laminar, crystal-like or quasi-ordered structures; see [13]) and also the variability within each class. To illustrate this point, consider that, for all structurally coloured materials, achieving peak reflectance in visible wavelengths depends on three general features: nanoscale organization, size of scattering structures and refractive index (RI) contrast of its structural components. Moreover, these materials can be organized into one (e.g. multilayer reflectors [11]), two (e.g. two-dimensional photonic crystals (PCs) [9]) or three dimensions (e.g. amorphous matrices [14]), and in birds they are produced by a rather limited set of basic materials: keratin, melanin and air [13]. Optical theory shows that slight alterations in organization, size or RI contrast in these nanostructures can lead to dramatic changes in colour [15]. However, the theoretical and empirical variability of any single class of nanostructure have not been thoroughly explored.

In many duck species, the secondary flight feathers bear an iridescent wing patch known as the speculum [16] that exhibits a broad range of interspecific colour variation [17]. Previous studies have suggested that this colour arises through multilayer interference from organized rows of thin melanosomes and layers of keratin [18–20]. However, electron micrographs of barbule cross sections show a two-dimensional hexagonal arrangement of melanosomes beneath a thin keratin cortex [18], suggesting that colour may in fact result from a two-dimensional PC. Such crystals can produce a broad variety of colours, and are thus an ideal study system for examining the variability of a structural colour class. We did so using a combination of electron microscopy, reflectance spectroscopy and optical modelling. First, we identified the colour-producing nanostructure in six duck species. Second, using optical modelling, we compared the observed variation in this nanostructure and the colour it produces to what is theoretically possible given all potential combinations of relevant morphological parameters (radius, spacing) that are able to produce bird-visible coloration.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study system

To investigate the morphological bases of interspecific variation in speculum colour, we chose six species from the monophyletic dabbling duck clade (tribe Anatini) [21]. We removed a single iridescent secondary feather from the left wing of males from four of the six species using dissecting scissors for subsequent electron microscopy (see below) and used published data for Speculanas specularis and Amazonetta brasiliensis [18] to obtain close to the whole range of colours observed in ducks (table 1; electronic supplementary material, figure S1). We stored feathers in small envelopes in a climate-controlled room until further analysis.

Table 1.

List of species and measured colour of iridescent speculum feathers (one measurement per species) in dabbling ducks (Anseriformes: Anatidae). Columns indicate peak location (hue), height (peak reflectance) and full width of main peak at half maximum (FWHM). Superscript letters next to species names indicate source of feather samples.

| species | hue (nm) | peak reflectance (%) | FWHM (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anas platyrhynchosa | 462 | 14.96 | 77 |

| Amazonetta brasiliensisb | 514 | 49.84 | 102 |

| Anas carolinensisa | 525 | 45.95 | 69 |

| Anas clypeataa | 551 | 10.67 | 87 |

| Anas acutaa | 600 | 15.15 | 93 |

| Speculanas specularisb | 642 | 61.83 | 84 |

aUniversity of Akron, Akron, OH, USA.

bUniversity of Michigan Museum of Zoology, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

2.2. Barbule nanostructure

To test the hypothesis that speculum colour results from a heterostructure consisting of a keratin thin-film and two-dimensional hexagonal lattice of melanosomes in feather barbules, we examined barbule nanostructure by preparing cross sections following Shawkey et al. [22]. Briefly, we washed feather barbs in 0.25 M NaOH and 0.1 per cent Tween-20, dehydrated them with 100 per cent ethanol and infiltrated them with 15, 50, 70 and 100 per cent epoxy resin. We then cured the resin blocks in an oven at 60°C, trimmed them with a Leica S6 EM-Trim 2 (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) and cut 100 nm cross sections with a Leica UC-6 ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). Next, we viewed the cross sections on a JEOL JEM-1230 transmission electron microscope (TEM) operating at 120 kV. From the obtained TEM images, we used ImageJ [23] to measure the following nanostructural parameters from two to three barbules per species: keratin cortex thickness (d), taken at 10 evenly spaced locations along the surface of each barbule; number of ordered melanosome layers (i.e. periods, defined as a layer in which three to four consecutive melanosomes were in the same plane); melanosome radius (r); and melanosome spacing (distance between their centres; i.e. lattice constant a; figure 1a). For the latter two variables, we used the particle analysis tool in ImageJ to determine the x and y coordinates and areas of 30–80 melanosomes per barbule (sample sizes were unequal because of variation in the number of visible melanosomes in a given cross section). Next, we determined the area (A) and nearest neighbour distance (NND) between melanosomes and calculated the lattice constant as the mean NND and the radius as  . For S. specularis and A. brasiliensis, we used published values of r and d and derived a from the available TEM images [18].

. For S. specularis and A. brasiliensis, we used published values of r and d and derived a from the available TEM images [18].

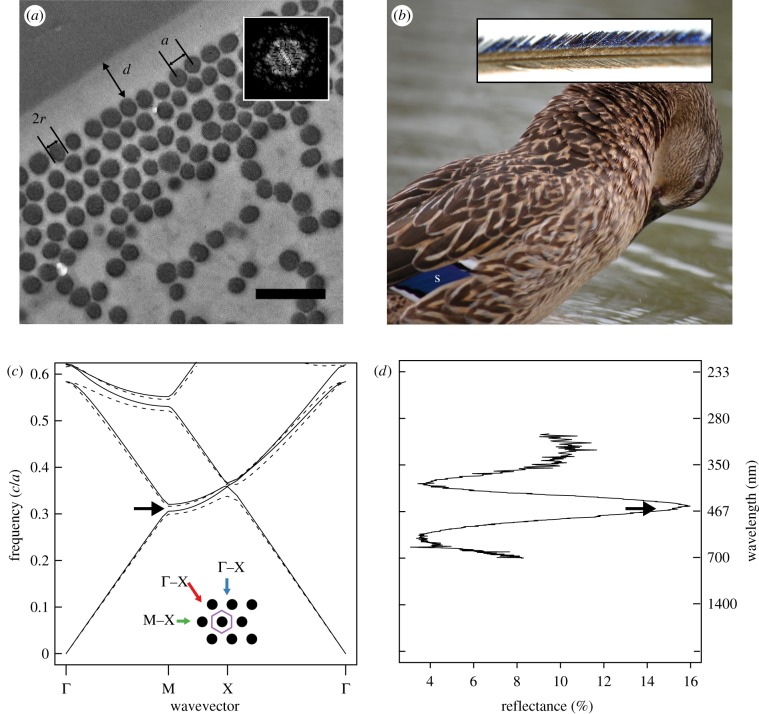

Figure 1.

Feather nanostructure and colour-producing mechanism in iridescent duck feathers. (a) Representative cross section of an iridescent feather barbule taken from the speculum feather of a mallard (A. platyrhynchos) showing measured parameters a (lattice constant), 2r (melanosome diameter) and d (cortex thickness). Inset shows Fourier transformation of region pictured in (a), illustrating hexagonal periodicity of melanosomes. (b) Photograph of a female mallard showing location of speculum (s) and light microscope image of a feather barb (inset). (c) Band structure diagram of two-dimensional hexagonal lattice of melanin rods (r/a = 0.44; RI = 2.0) embedded in keratin (RI = 1.56); lines represent modes for s- (E-field parallel to rods; dashed lines) and p-polarized light (E-field perpendicular to rods; solid lines), and black arrow shows location of partial photonic band gap (PBG). Inset shows schematic diagram of barbule cross section (unit cell, purple hexagon), depicting light incident along Γ–M (blue arrow), M–X (green arrow) and X–Γ directions (red arrow). (d) Plot of feather reflectance at corresponding frequencies in (c) with wavelength shown on secondary y-axis; black arrow shows location of partial PBG as in (c).

2.3. Reflectance measurements

2.3.1. Overview of spectral analysis

With the exception of colour measurements taken from intact wing patches (see §2.3.2–2.3.4), we took all reflectance measurements using a laboratory-made goniometer [24] that allowed us to independently vary the angles of incidence (θi) and reflectance (θr). For polarization measurements, we used a Glan-Thompson polarizer (Harrick Scientific Products, Pleasantville, NY, USA) placed between the light source and sample (electronic supplementary material, figure S2). We took unpolarized reflectance measurements at normal incidence for all six species (using intact plumages) and measured polarized reflectance and angle-resolved reflectance spectra for Anas carolinensis, Anas platyrhynchos, Anas acuta and Anas clypeata.

2.3.2. Normal incidence

To compare empirical reflectance with that predicted by optical modelling (see §2.5), we measured specular reflectance of intact wing patches at normal incidence from 300 nm to 700 nm using a spectrophotometer and xenon light source (Avantes Inc., Broomfield, CO, USA). We took the average of three separate measurements per bird and smoothed reflectance values with a spline function to remove electrical noise from the spectrophotometer and thereby increase the accuracy of colour variable measurements [25]. Next, we calculated hue ( ), brightness (peak reflectance Rmax) and saturation (full-width of main peak at half of maximum; FWHM). For FWHM, we calculated the width of the peak (in nanometres) at the midpoint of the difference between the minimum and maximum reflectance values, resulting in a variable that is inversely proportional to perceived saturation. These measures of hue and saturation correspond to the centre frequency and width of photonic band gaps (PBGs), respectively [26], thereby allowing for direct comparison with optical model predictions.

), brightness (peak reflectance Rmax) and saturation (full-width of main peak at half of maximum; FWHM). For FWHM, we calculated the width of the peak (in nanometres) at the midpoint of the difference between the minimum and maximum reflectance values, resulting in a variable that is inversely proportional to perceived saturation. These measures of hue and saturation correspond to the centre frequency and width of photonic band gaps (PBGs), respectively [26], thereby allowing for direct comparison with optical model predictions.

2.3.3. Polarized reflectance

Owing to periodicity in RI parallel to the surface, reflectance of a two-dimensional PC measured at normal incidence is expected to vary depending on the polarization of incident light [15]. While similar polarization effects also occur in multilayered (one-dimensional) structures, they are typically observed only at high incident angles [27]. Therefore, to help distinguish between two alternative hypotheses for colour production, namely a one-dimensional multilayer or two-dimensional photonic heterostructure, we measured s- and p-polarized specular reflectance at near-normal incidence (θi = 10°) for three feather samples: a hypothesized two-dimensional PC (green-winged teal, A. carolinensis); a positive control known to behave as a two-dimensional PC (peacock, Pavo cristatus) [9]; and a negative control with a likely multilayered (one-dimensional) structure (ruby-throated hummingbird, Archilochus colubris) [12]. We predicted that both the peacock and duck samples would show differences in hue based on polarization, while the hummingbird sample would not.

2.3.4. Angle-resolved reflectance

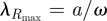

To understand the angle-dependent reflectance behaviour of these samples, we measured specular reflectance for s- and p-polarized light at multiple incident angles (θi = 10°, 20°, 30°, 40°, 50°, 60° and 70°) and azimuthal angles (Φ) perpendicular and parallel to the barbules. Because light-scattering requires a difference in RI, the homogeneity of one-dimensional layered systems in the x and y directions (parallel to surface) implies that Φ should have no effect on angle-resolved reflectance for different polarizations of light, while it should have the same for a two-dimensional PC. Thus, we calculated the ratio of p- to s-polarized peak reflectance (Rp/Rs) and plotted this ratio versus θi for Φ = 0° (parallel to barbules) and 90° (perpendicular to barbules). This ratio is suitable for small or anisotropic samples where the aperture of reflected light is expected to vary with orientation: since the aperture is the same for each polarization at a given orientation, the ratio remains unaffected [28]. Based on the band structure diagram (figure 1c), we predicted that the ratio Rp/Rs would be greater when the plane of incidence is parallel to the melanosomes and that the differences would diminish as θi approaches Brewster's angle, at which the reflectance would be dominated by thin-film effects (zero p-polarized reflectance from the top air–keratin interface at both orientations).

2.4. Refractive index-matching experiments

Light incident on a thin-film structure produces colour by interference between beams of light reflecting from the top and bottom interfaces of the film. Thus, to empirically examine the role of the keratin cortex in colour production, we removed its effects by placing wintergreen oil (Frontier Natural Products, Norway, IA, USA) on the surface of each feather. Because the RI of the oil is approximately equal to that of keratin (RI = 1.54 and 1.56, respectively), Fresnel reflectivity from the top interface is effectively eliminated. Further, to eliminate unwanted reflection of light at the air–oil interface, we mounted a bifurcated fibre-optic probe at a fixed distance from the feather surface and immersed it in the oil. We measured specular reflectance at normal incidence and compared the mean hue, saturation and brightness before and after adding oil.

2.5. Optical modelling

2.5.1. Band structure calculation

The band structure of a PC gives the frequencies of light that are able to propagate through a periodic structure as a function of the light polarization and wavevector [15]. Frequencies that are unable to propagate through the structure comprise the PBG and are reflected from the PC. Thus, to investigate the physical mechanism of colour production, we used the standard plane-wave expansion method implemented in the software package MPB [29] to calculate the band structure of an idealized hexagonal lattice based on experimental values for the ratio between melanosome radius and spacing (r/a, an indicator of melanosome density) and published values for the refractive indices of keratin (RI = 1.56) and melanin (RI = 2.00) [30,31]. From the resulting band structure diagrams, we calculated the size of the partial PBG (Δω) at normal incidence and standardized this value by dividing it by the band gap position (ω), as band gap size is known to vary with position [15].

To determine the theoretical range of values for lattice constant and radius that would produce a primary PBG in bird-visible wavelengths (300–700 nm), we used MPB to simulate band structures for a range of values of r/a between 0 and 0.5 and calculated the resulting position (ω) and size (Δω) of the partial PBG. We chose this range to cover all theoretically possible configurations up to a limiting value of r/a = 0.5, at which the melanosomes would be directly in contact with each other (i.e. hexagonal close-packing). Next, because hue depends on the lattice constant, we calculated hue as  [15] for a range of lattice constants (a = 80–250 nm, in 10 nm increments) specified a priori to give hues spanning the desired range, 300–700 nm. We then plotted the band gap size versus a and r and overlaid the plot with the calculated hues falling within the bird-visible spectrum of light.

[15] for a range of lattice constants (a = 80–250 nm, in 10 nm increments) specified a priori to give hues spanning the desired range, 300–700 nm. We then plotted the band gap size versus a and r and overlaid the plot with the calculated hues falling within the bird-visible spectrum of light.

2.5.2. Predicted reflectance

Dyck [20] described the nanostructures in ducks as multilayers composed of melanin and keratin, with the thickness of layers equal to the diameter of melanosomes and space between melanosomes, respectively. However, in several of the close-packed structures, we observed that there is little to no space between melanosomes, making this model unrealistic, and thus we did not test this model here. We instead modelled the nanostructures as hexagonal two-dimensional PCs using the finite-difference time-domain method implemented in MEEP (MIT Electromagnetic Equation Propagation) [32]. We chose this method because it allowed us to calculate reflectance across a range of wavelengths (i.e. 300–700 nm) in a single simulation. We simulated reflectance spectra in MEEP based on measured nanomorphological values (a, r, d and melanosome layer number) for each barbule per species. In addition, to understand the role of the cortex in colour production, we compared predicted reflectance calculated when excluding and including the cortex with empirical results of RI-matching experiments (see below). In our simulations, we excluded the cortex by setting the RI surrounding the structure to that of keratin (RI = 1.56), thereby eliminating reflection from the air–keratin interface. For all simulations, we used an extinction coefficient for melanin of 0.01 [9,33] and published values for the refractive indices of keratin (RI = 1.56) and melanin (RI = 2) [30,31]. We then compared theoretical with empirical reflectance curves to test the accuracy of our modelling.

2.6. Statistics

We performed all statistical analyses in R v. 14.0 [34]. All values are presented as mean ± 95% confidence limits unless otherwise noted.

3. Results

3.1. Barbule morphology

In all six species examined, TEM images of barbule cross sections revealed a two-dimensional hexagonal array of melanosomes underlying a thin keratin cortex (figure 1a). The size of melanosomes (radius) ranged from 60 nm to 85 nm and their spacing (lattice constant) varied from 140 nm to 200 nm (table 2). The cortex thickness ranged from 90 nm to 370 nm, and the number of melanosome layers varied from four to six across species (table 2).

Table 2.

Iridescent barbule nanomorphology in dabbling ducks (Anseriformes: Anatidae). Values shown are species means and 95% CLs for nanomorphological measurements taken from TEM images of barbule cross sections. N indicates number of barbules (melanosomes) analysed, with all barbules sampled from the same feather of one individual per species.

| species | N | lattice constant (nm) | radius (nm) | cortex (nm) | periods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anas platyrhynchos | 2 (133) | 139.36 ± 1.99 | 59.71 ± 1.02 | 295.19 ± 5.17 | 5.5 |

| Amazonetta brasiliensis | n.a.a | 153 | 65 | 90 | 5 |

| Anas carolinensis | 2 (107) | 153.49 ± 3.12 | 69.81 ± 1.16 | 361.76 ± 11.27 | 5.5 |

| Anas clypeata | 2 (69) | 148.93 ± 2.56 | 72.72 ± 1.55 | 258.06 ± 19.79 | 5 |

| Anas acuta | 3 (151) | 159.50 ± 3.74 | 75.12 ± 1.42 | 357.36 ± 8.44 | 4.67 |

| Speculanas specularis | n.a.a | 198 | 85 | 330 | 6 |

aMeasurements for species taken from published data [18]. Cortex thickness variation estimated from 10 measurements per barbule. Values without 95% CL indicate insufficient data available for estimation (see text for further details).

3.2. Reflectance measurements

3.2.1. Normal incidence

All reflectance curves showed primary reflection peaks between 462 nm and 642 nm, and most curves were multi-peaked, with one to two minor secondary peaks occurring at shorter wavelengths (figure 2a,c–f). Of the six species examined, only A. brasiliensis had a single peak at 514 nm (figure 2b), while A. acuta and S. specularis had additional tertiary peaks occurring at 300 nm and 325 nm, respectively (figure 2e,f). The primary peaks were highly saturated (narrow), with FWHM values ranging from 69 nm to 102 nm (e.g. compare with FWHM approx. 170 nm for yellow peacock feathers in the study of Yoshioka & Kinoshita [33]). Hue increased strongly with melanosome size (electronic supplementary material, figure S3a) and, to a lesser extent, lattice constant (electronic supplementary material, figure S3b) but did not appear to be related to either cortex thickness or number of melanosome layers. Peak reflectance (brightness) varied considerably between species, ranging from 10.67 (A. clypeata) to 61.83 per cent (S. specularis) (table 1), and increased slightly with the number of melanosome layers (periods) and decreased with melanosome density (r/a) (electronic supplementary material, figure S3c,d, respectively).

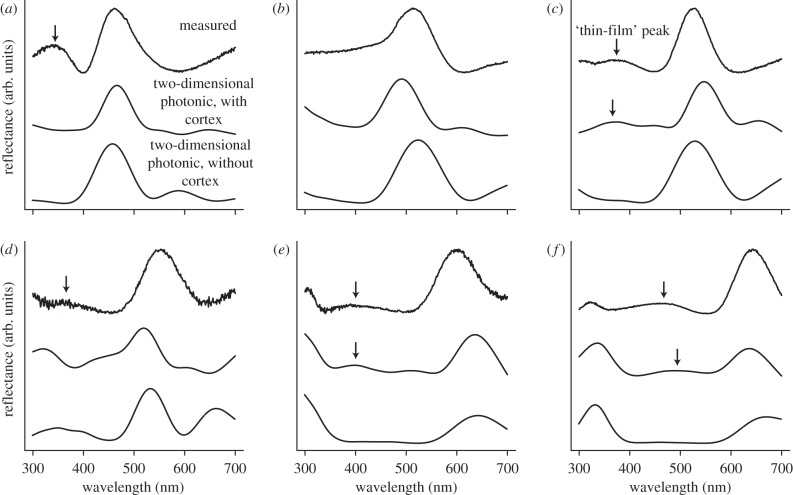

Figure 2.

Agreement between measured and predicted reflectance based on two-dimensional hexagonal photonic crystal (PC) and two-dimensional heterostructure optical models. Panels show empirical and simulated reflectance curves (normalized to maximum of unity and based on representative nanomorphologies) for (a) A. platyrhynchos, (b) Amazonetta brasiliensis, (c) A. carolinensis, (d) Anas clypeata, (e) Anas acuta and (f) Speculanas specularis. In each panel, the top curve is empirical reflectance, the middle curve is the full PC model predictions (two-dimensional PC + cortex) and the bottom curve is the reduced PC model (excluding the cortex). To remove unwanted spectral noise, predicted spectra were smoothed with cubic splines using the SMOOTH.SPLINE function in R 14.0 [34] (equivalent degrees of freedom = 17, smoothing parameter = 0.65). Arrows indicate location of thin-film peaks (see text for description).

3.2.2. Polarized light

The wavelength of peak reflectance ( ) for p-polarized light at near-normal incidence was shifted to slightly longer wavelengths than s-polarized light, and the peak reflectance increased slightly (electronic supplementary material, figure S4). This observed bathochromic shift was also seen in a known two-dimensional PC structure (peacock) but not in a negative control (hummingbird; electronic supplementary material, figure S4). Furthermore, peak reflectance did not change for the hummingbird (one-dimensional multilayer) but was higher for s-polarized light in the peacock.

) for p-polarized light at near-normal incidence was shifted to slightly longer wavelengths than s-polarized light, and the peak reflectance increased slightly (electronic supplementary material, figure S4). This observed bathochromic shift was also seen in a known two-dimensional PC structure (peacock) but not in a negative control (hummingbird; electronic supplementary material, figure S4). Furthermore, peak reflectance did not change for the hummingbird (one-dimensional multilayer) but was higher for s-polarized light in the peacock.

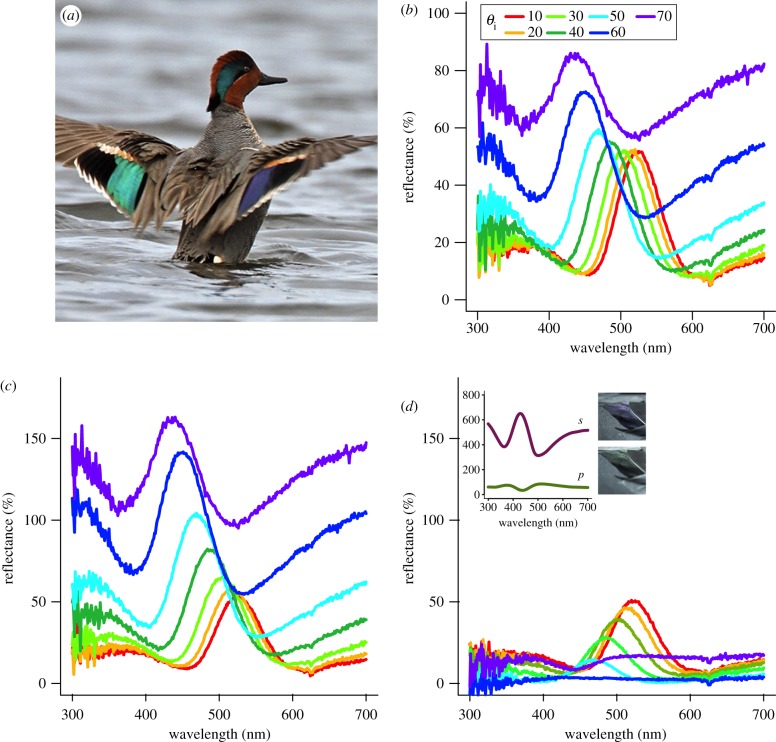

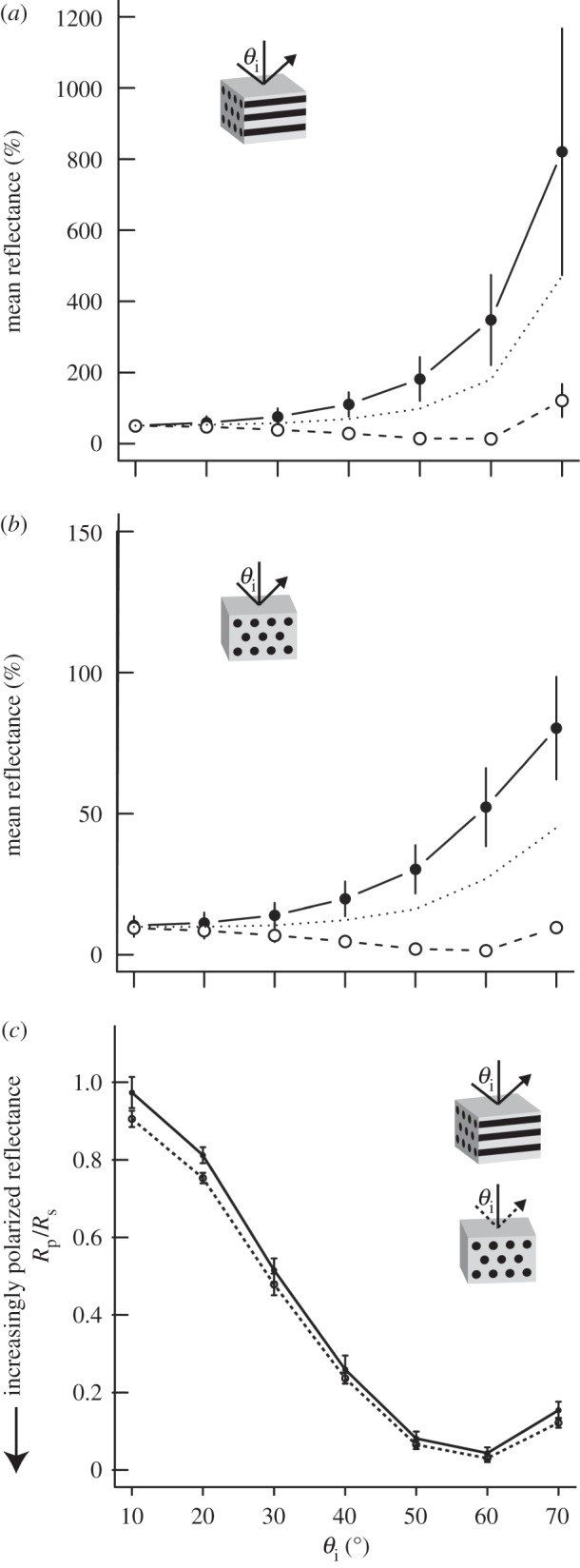

3.2.3. Angle-resolved spectra

All analysed feathers showed significant changes in reflectance with increasing incident angle (figures 3b, 4a,b, dotted lines). Furthermore, these angle-dependent reflectance changes varied with polarization. For s-polarized light, reflectance increased with θi (figure 4a,b, solid lines). By contrast, p-polarized reflectance steadily decreased until reaching a minimum at θi ∼ 60° and then began to increase (figure 4a,b, dashed lines). We observed phase inversions in the reflectance spectra for all samples analysed (see figure 3d, inset). Furthermore, feather barbule orientation affected angle-resolved reflectance for s and p polarizations, as light incident perpendicular to the barbules was in general more polarized (Rs > Rp) than light with parallel incidence; however, as θi approached approximately 60°, these differences diminished (figure 4c).

Figure 3.

Effects of incident angle and light polarization on specular reflectance of green-winged teal feathers. Male teal shown to illustrate colour changes with incident angle θi in speculum feathers; note that the left wing patch (speculum) is green, while the right one is violet–blue (a). Reflectance spectra for unpolarized light at various incident angles (b). Specular reflectance of s- (c) and p-polarized light (d) at various incident angles (θi) with incident plane perpendicular to barbules; line colours as in (b). Inset in (d) shows reflectance curves at θi = 70° with corresponding images of same feather at each polarization (note inverted shape of curves). (a) Adapted from M. Lamarche.

Figure 4.

Effects of barbule orientation and incident angle on polarized light reflectance of iridescent duck feathers. (a,b) Mean peak reflectance (N = 4 species) at various incident angles (θi) for s-polarized light (solid line, filled circles), p-polarized light (dashed line, open circles) and the average of both polarizations (dotted line) with incident plane either parallel (a) or perpendicular to feather barbules (b). Note the difference in y-axis scale; vertical bars represent ±s.e. (c) Ratio of p- to s-polarized light reflectance (Rp/Rs) of iridescent feathers with incident plane parallel (solid line) or perpendicular to melanosome axes (dashed line).

3.3. Refractive index-matching experiment

When oil was placed on the surface of feathers, the hue did not change substantially (hue before: 538 ± 83 nm; after: 542 ± 97 nm; electronic supplementary material, figure S5), suggesting that the structural coloration is produced in part by the underlying two-dimensional PC structure. Feather colour, however, became less saturated (FWHM before: 82 ± 11 nm; after: 136 ± 49 nm) and less bright after treatment (brightness before: 66.5 ± 75.1; after: 18.5 ± 28.2). Additionally, all curves lacked the observed peak in the UV region (electronic supplementary material, figure S5). These results were confirmed by simulated reflectance data, which showed little change in hue (hue before: 542 ± 95 nm; after: 539 ± 127 nm) but decreases in both saturation (FWHM before: 60 ± 19 nm; after: 80 ± 30 nm) and brightness (before: 26.30 ± 12; after: 17.4 ± 13).

3.4. Optical modelling

Based on barbule nanostructural parameters, the calculated band structure for a two-dimensional hexagonal lattice indicated a partial PBG at ω ∼ 0.3 for both s- and p-polarizations in the direction normal to the barbule surface (Γ–M; blue arrow in figure 1c). The standardized range of frequencies reflected by the PC (gap-midgap ratio Δω/ω) was 3.05 ± 1.51%. There was an additional band gap in the M–X direction at ω ∼ 0.6; however, this would not contribute to the observed colour as the peak would occur outside of the visible region of the spectrum for all lattice constants analysed here. The slight increases in both hue (3 nm) and reflectance for p-polarized light at near-normal incidence (electronic supplementary material, figure S4) mirror the subtle shift to lower frequencies (from ω = 0.313 to 0.308) and subtle widening of the partial PBG (from Rmax = 4.69% to 5.56%) taken from the calculated band structure (figure 1c). Moreover, this behaviour is expectedly different from the change in reflectance observed in peacock feathers, as the gap for p-polarized light narrows slightly (fig. 3 in Zi et al. [9]).

The simulated reflectance spectra based on the full PC model (model including the cortex) closely matched the experimental curves (figure 2). Furthermore, in most cases, the heterostructure model performed better than the model excluding the effects of the keratin cortex and only considering the melanosome two-dimensional lattice (figure 2). Indeed, while both PC models predicted the location of the primary peak, only the full PC model predicted the shallow peaks (‘thin-film’ peaks) occurring between 350 nm and 500 nm (figure 2c,e–f). For both PC models, predicted and measured hues were highly similar, differing only between 7 nm and 36 nm (full PC model) or between 4 nm and 33 nm (reduced PC model).

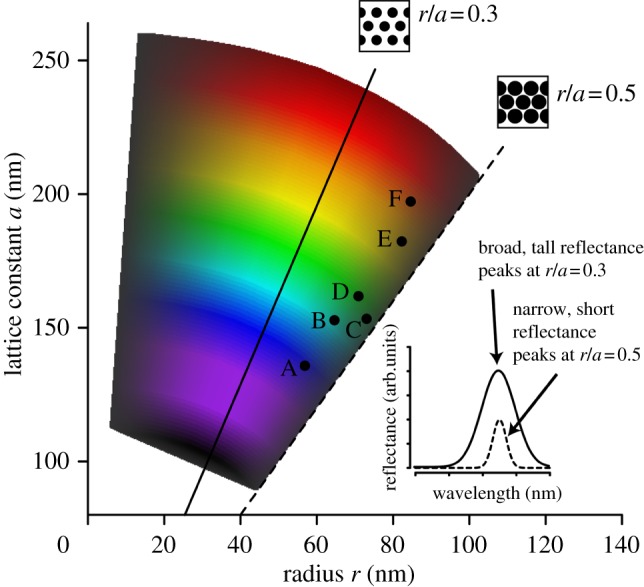

Theoretical simulations of band gap size for various values of r and a showed a maximum at r/a = 0.3 (figure 5, solid line) and local minima at 0.05 and 0.5 (figure 5, dashed line). Most species were located near the close-packing limit (r/a = 0.5); however, hue spanned a range of wavelengths from blue (A. platyrhynchos) to red (S. specularis), and no species had a partial PBG peak below 400 nm (figure 2).

Figure 5.

Theoretically possible colours of two-dimensional photonic crystal structure in ducks compared with observed values. Coloured polygon depicts simulated band gap sizes (lightness of colour) and hues (shade of colour) for a range of possible values for melanosome radius and lattice constant, showing a maximum band gap at r/a = 0.3 (solid line) and a minimum at r/a = 0.5 (the close-packing limit; dashed line). Labelled points represent observed nanostructural dimensions (same values used in figure 2) for six species of duck: A. platyrhynchos (A), Amazonetta brasiliensis (B), Anas carolinensis (C), A. clypeata (D), A. acuta (E) and Speculanas specularis (F). Schematic drawings show melanosome configurations (black circles) at r/a = 0.3 and 0.5; inset shows hypothetical reflectance curves for each configuration.

4. Discussion

Our results show that iridescent colours of duck specula are produced by two-dimensional hexagonal PCs of rod-shaped melanosomes embedded below a thin layer of keratin at the surface of feather barbules (figure 1a). Our empirical and theoretical results show that this system is potentially highly variable, allowing for changes in coloration through slight variations in lattice constant, melanosome radius and cortex thickness. However, the structural variability of the biophotonic structure possessed by all six species examined here may be limited within ducks to a relatively small portion of theoretically available configurations (i.e. close-packed hexagonal arrays; see also the study of Kinoshita [35]).

Two-dimensional PCs have previously been described in peacocks [9] and magpies [36]. However, these differ from those found in ducks because they are square rather than hexagonal lattices [9]; have air rather than keratin between melanosomes [9]; and have hexagonally spaced air-spaces rather than filled melanosomes [36]. Hexagonal PCs are ideal for achieving complete PBGs because of their near-circular periodicity (figure 1a, inset); thus these results may have implications for the design of novel photonic structures [37]. Furthermore, in the above cases, the keratin cortex apparently had little effect, possibly because it was too thick or discontinuous to cause marked interference at visible wavelengths. By contrast, in all duck species examined here, the cortex produced interference effects as indicated by secondary reflectance peaks at shorter wavelengths (figure 2 and electronic supplementary material, S5). Further, we show that the cortex increases brightness and saturation—possibly owing to resonance occurring as a result of size matching between the thickness of the one-dimensional film (cortex) and lattice constant (melanosome spacing) of the two-dimensional PC [38]—and results in polarized iridescence (figures 3 and 4). While the role of the keratin cortex in colour production has been studied in other iridescent bird species [11,12], to our knowledge, this is the first study to show the optical properties arising from both one-dimensional and two-dimensional periodicity, rather than a one-dimensional multilayer. Thus, our results describe a novel, variable biophotonic heterostructure, as well as an additional parameter (cortex thickness) that can potentially be independently tuned to achieve different colours.

Previous studies of speculum colour in ducks ascribed it to a multilayer (one-dimensional PC) [18–20]. Although the observed increase in s-polarized light and decrease in p-polarized light with incident angle (figures 3 and 4) is characteristic of both multilayered (one-dimensional) structures [27] and two-dimensional PCs (see description in Bazhenova et al. [39]), the differences in depolarization with θi for different azimuthal angles (figure 4) are not consistent with a one-dimensional system because there is no periodicity in RI parallel to the surface to differentially scatter light incident from different directions. Interestingly, multilayer-like behaviour, namely the inversion in reflectance curves past θc, was observed in these samples (figure 3d, inset). Based on nanostructural data and known fundamentals of optics—specifically, that p-polarized light incident on a thin-film undergoes a 180° phase shift past Brewster's angle [39]—the observed behaviour (inverted reflectance curve) is thus the result of destructive interference occurring between light beams reflecting from the air–keratin interface and the PC. Thus, contrary to previous hypotheses [18–20], our modelling and polarization data are consistent with a photonic heterostructure and not a multilayer.

The evolvability of complex structures is determined by the underlying mechanisms of control (e.g. genetic, physical) and also the relative independence (modularity) between component traits that comprise the overall structure [6]. Variable structures that can readily assume viable new forms, such as pharyngeal jaw structure in cichlids or beaks in Darwin's finches, have facilitated adaptive radiation in these clades [40]. Our simulations suggest that this colour-producing nanostructure is similarly variable and that indeed, it is capable of producing many variants of colours across the visible spectrum (figure 5). Moreover, our empirical results show that ducks have exploited this feature and, through slight variations in the size and spacing of their melanosomes, have produced diverse colours ranging from violet to red (figure 2). However, developmental or physical mechanisms can also constrain trait evolution [41]. In this case, physical constraints set an upper bound on the relationship between melanosome radius and spacing: because two melanosomes cannot occupy the same space, it is impossible for the melanosome radius to be more than half the distance between melanosomes (i.e. r/a cannot be greater than 0.5). However, by increasing the space between melanosomes (i.e. achieving r/a < 0.5), ducks can increase the size of their partial PBG and hence range of frequencies reflected up to a maximum occurring at r/a = 0.3 (centre of polygon in figure 5). Thus, ducks could potentially maximize their feather brightness by moving towards this band gap region. However, all six species examined lie in the small PBG region of figure 5 near the close-packing limit of r/a = 0.5. Because small band gaps are associated with short, narrow reflectance peaks (figure 5, inset), these results suggest that physical limits on nanostructural configuration (close-packing) may constrain ducks to less bright but highly saturated feather colours. Additionally, melanosome size in birds also appears to be constrained to diameters above approximately 100 nm [42,43], further restricting the range of colours capable of being produced by ducks to hues greater than approximately 400 nm (figures 2 and 5). However, whether ducks are able to perceive UV wavelengths is controversial [44–46]; thus UV colours may not be advantageous, at least in an intraspecific signalling context.

Recent evidence suggests that structurally coloured feathers develop through processes of self-assembly [47,48]. Furthermore, a close-packed hexagonal configuration is highly energetically stable and is thus a likely end-product of a self-assembly process [49,50]. Indeed, self-assembly of rods into a two-dimensional lattice has recently been observed in artificial colloid solutions of nanorods: as the solvent evaporated around them, the rods became highly aligned and hexagonally close-packed [51]. Other configurations with greater distance between melanosomes are not as stable and are thus less likely to form [50]. This limitation of development may therefore constrain duck colours to relatively close-packed, high-saturation configurations. Alternatively, this limited diversity may be caused by sexual selection favouring highly saturated colours (reviewed by Hill [52]). We are currently using phylogenetic methods in a theoretical morphospace to test these hypotheses across a broader sampling of dabbling duck species.

Despite the aforementioned constraints on colour-production, the colours of mallard specula are diverse. In many duck species, males display their colourful wing patches during pre-copulatory interactions [53], suggesting that iridescent speculum colour may evolve through sexual selection [2]. However, the experimental removal of the iridescent speculum in mallards did not have any effect on pairing success in male mallards (A. platyrhynchos) [54]. More recently, a test for condition-dependent expression (a key prediction for the indicator mechanism of evolution by sexual selection) revealed positive correlations between colour and body condition in females, but not in males [55]. Thus, evidence for a signalling function is mixed. Colourful speculum feathers in ducks may also function in reproductive isolation and species recognition (reviewed by Ritchie [56]). Despite the ubiquity of viable and fertile hybrids in ducks [57], sympatric species remain distinct [58], suggesting the existence of pre-zygotic reproductive isolation mechanisms, like species-specific colour patches. If these hybrids are less fecund than non-hybrids, then speculum colours may be adaptations for reinforcement, potentially following secondary contact after allopatric speciation [59,60]. If not, then the colours themselves may drive speciation through drift, similar to that seen in Carduelis finches [61], and could be a rare example of diversification through a non-adaptive key innovation.

Future studies should investigate the genetic and physical mechanisms of control that result in this complex photonic structure, as well as the level of modularity between components. The answers to such questions could provide clues to the potential ecological and evolutionary forces driving colour variation in birds.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank R. Maia for help with electron microscopy, L. D'Alba for her comments on an earlier manuscript and J. Luettmer-Strathmann for help with optical modelling. This work was supported by University of Akron startup funds and AFOSR grant FA9550-09-1-0159 (both to M.D.S.).

References

- 1.Parker A. R. 2000. 515 million years of structural colour. J. Opt. A: Pure Appl. Opt. 2, R15–R28 10.1088/1464-4258/2/6/201 (doi:10.1088/1464-4258/2/6/201) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson M. 1994. Sexual selection. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cott H. B. 1940. Adaptive coloration in animals. London, UK: Methuen Ltd [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burtt E. H. 1986. The behavioral significant of color. New York, NY: Garland Publishing, Inc [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoddard M. C., Prum R. O. 2011. How colorful are birds? Evolution of the avian plumage color gamut. Behav. Ecol. 22, 1042–1052 10.1093/beheco/arr088 (doi:10.1093/beheco/arr088). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner G. P., Altenberg L. 1996. Perspective: complex adaptations and the evolution of evolvability. Evolution 50, 967–976 10.2307/2410639 (doi:10.2307/2410639) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGraw K. J. 2006. Mechanics of uncommon colors: pterins, porphyrins, and psittacofulvins. In Bird coloration: mechanisms and measurements, vol. I (eds Hill G. E., McGraw K. J.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersson S. 1999. Morphology of UV reflectance in a whistling-thrush: implications for the study of structural colour signalling in birds. J. Avian Biol. 30, 193–204 10.2307/3677129 (doi:10.2307/3677129) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zi J., Yu X. D., Li Y. Z., Hu X. H., Xu C., Wang X. J., Liu X. H., Fu R. T. 2003. Coloration strategies in peacock feathers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 12 576–12 578 10.1073/pnas.2133313100 (doi:10.1073/pnas.2133313100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yin H., et al. 2006. Iridescence in the neck feathers of domestic pigeons. Phys. Rev. E 74, 51 916. 10.1103/PhysRevE.74.051916 (doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.74.051916) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stavenga D. G., Leertouwer H. L., Marshall N. J., Osorio D. 2010. Dramatic colour changes in a bird of paradise caused by uniquely structured breast feather barbules. Proc. R. Soc. B 278, 2098–2104 10.1098/rspb.2010.2293 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.2293) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenewalt C. H., Brandt W., Friel D. D. 1960. The iridescent colors of hummingbird feathers. Proc. Am. Phil. Soc. 104, 249–253 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prum R. O. 2006. Anatomy, physics, and evolution of structural colors. In Bird coloration: mechanisms and measurements, vol. I (eds Hill G. E., McGraw K. J.), pp. 295–353 Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prum R. O., Torres R., Williamson S., Dyck J. 1998. Coherent light scattering by blue feather barbs. Nature 396, 28–29 10.1038/23838 (doi:10.1038/23838) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joannopoulos J. D., Johnson S. G., Winn J. N., Meade R. D. 2008. Photonic crystals: molding the flow of light, 2nd edn Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- 16.Humphrey P. S., Clark G. A., Jr 1961. Pterylosis of the mallard duck. Condor 63, 365–385 10.2307/1365296 (doi:10.2307/1365296) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madge S., Burn H. 1998. Wildfowl: an identification guide to the ducks, geese and swans of the world. London, UK: Christopher Helm [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutschke E. 1966. Die submikroskopische struktur schillernder federn von entenvögeln. Zeitschrift für Zellforschung 73, 432–443 10.1007/BF00329021 (doi:10.1007/BF00329021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durrer H. 1977. Schillerfarben der vogelfeder als evolutionsproblem. Denkschriften der Schweizerischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft 91, 1–127 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dyck J. 1976. Structural colours. Proc. Int. Ornithol. Congr. 16, 426–437 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson K. P., Sorenson M. D. 1999. Phylogeny and biogeography of dabbling ducks (genus: Anas): a comparison of molecular and morphological evidence. Auk 116, 792–805 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shawkey M. D., Estes A. M., Siefferman L. M., Hill G. E. 2003. Nanostructure predicts intraspecific variation in ultraviolet–blue plumage colours. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 270, 1455–1460 10.1098/rspb.2003.2390 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2390) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abramoff M. D., Magelhae P. J., Ram S. J. 2004. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophoton. Int. 11, 36–42 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meadows M. G., Morehouse N. I., Rutowski R. L., Douglas J. M., McGraw K. J. 2011. Quantifying iridescent coloration in animals: a method for improving repeatability. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 65, 1317–1327 10.1007/s00265-010-1135-5 (doi:10.1007/s00265-010-1135-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montgomerie R. 2006. Analyzing colors. In Bird coloration: mechanisms and measurements, vol. I (eds Hill G. E., McGraw K. J.), pp. 90–147 Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thijssen M. S., Sprik R., Wijnhoven J., Megens M., Narayanan T., Lagendijk A., Vos W. L. 1999. Inhibited light propagation and broadband reflection in photonic air-sphere crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 2730–2733 10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.2730 (doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.2730) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stavenga D. G., Wilts B. D., Leertouwer H. L., Hariyama T. 2011. Polarized iridescence of the multilayered elytra of the Japanese jewel beetle, Chrysochroa fulgidissima. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 366, 709–723 10.1098/rstb.2010.0197 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0197) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Avery D. G. 1952. An improved method for measurements of optical constants by reflection. Proc. Phys. Soc. Lond. B 65, 425–428 10.1088/0370-1301/65/6/305 (doi:10.1088/0370-1301/65/6/305) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson S., Joannopoulos J. 2001. Block-iterative frequency-domain methods for Maxwell's equations in a planewave basis. Opt. Express 8, 173–190 10.1364/OE.8.000173 (doi:10.1364/OE.8.000173) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brink D., van der Berg N. 2004. Structural colours of the bird Bostrychia hagedash. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 37, 813–818 10.1088/0022-3727/37/5/025 (doi:10.1088/0022-3727/37/5/025) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Land M. F. 1972. The physics and biology of animal reflectors. Progr. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 24, 75–106 10.1016/0079-6107(72)90004-1 (doi:10.1016/0079-6107(72)90004-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oskooi A. F., Roundy D., Ibanescu M., Bermel P., Joannopoulos J. D., Johnson S. G. 2010. MEEP: a flexible free-software package for electromagnetic simulations by the FDTD method. Comput. Phys. Commun. 181, 687–702 10.1016/j.cpc.2009.11.008 (doi:10.1016/j.cpc.2009.11.008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshioka S., Kinoshita S. 2002. Effect of macroscopic structure in iridescent color of the peacock feathers. Forma 17, 169–181 [Google Scholar]

- 34.R Development Core Team 2011. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation of Statistical Computing; See http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kinoshita S. 2008. Structural colors in the realm of nature. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vigneron J. P., Colomer J., Rassart M., Ingram A., Lousse V. 2006. Structural origin of the colored reflections from the black-billed magpie feathers. Phys. Rev. E 73, 021914. 10.1103/PhysRevE.73.021914 (doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.73.021914) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cassagne D., Jouanin C., Bertho D. 1996. Hexagonal photonic-band-gap structures. Phys. Rev. B 53, 7134–7142 10.1103/PhysRevB.53.7134 (doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.53.7134) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bardosova M., Pemble M. E., Povey I. M., Tredgold R. H., Whitehead D. E. 2006. Enhanced Bragg reflections from size-matched heterostructure photonic crystal thin films prepared by the Langmuir–Blodgett method. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 093 116. 10.1063/1.2339031 (doi:10.1063/1.2339031) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bazhenova A. G., Sel'kin A. V., Men'shikova A. Y., Shevchenko N. N. 2007. Polarization-dependent suppression of Bragg reflections in light reflection from photonic crystals. Phys. Solid State 49, 2109–2120 10.1134/S1063783407110169 (doi:10.1134/S1063783407110169) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schluter D. 2000. The ecology of adaptive radiation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwenk K. 1995. A utilitarian approach to evolutionary constraint. Zoology 98, 251–262 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Q., Gao K., Vinther J., Shawkey M. D., Clarke J. A., D'Alba L., Meng Q., Briggs D. E. G., Prum R. O. 2010. Plumage color patterns of an extinct dinosaur. Science 327, 1369–1372 10.1126/science.1186290 (doi:10.1126/science.1186290) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clarke J. A., Ksepka D. T., Salas-Gismondi R., Altamirano A. J., Shawkey M. D., D'Alba L., Vinther J., DeVries T. J., Baby P. 2010. Fossil evidence for evolution of the shape and color of penguin feathers. Science 330, 954–957 10.1126/science.1193604 (doi:10.1126/science.1193604) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jane S., Bowmaker J. K. 1988. Tetrachromatic colour vision in the duck (Anas platyrhynchos L.): microspectrophotometry of visual pigments and oil droplets. J. Comp. Physiol. A Sens. Neural Behav. Physiol. 162, 225–235 10.1007/BF00606087 (doi:10.1007/BF00606087) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parrish J., Smith R., Benjamin R., Ptacek J. 1981. Near ultraviolet light reception in mallard and passeriformes. Trans. Kansas Acad. Sci. 87, 147 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parrish J., Benjamin R., Smith R. 1981. Near ultraviolet light reception in the mallard. Auk 98, 627–628 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dufresne E. R., Noh H., Saranathan V., Mochrie S. G. J., Cao H., Prum R. O. 2009. Self-assembly of amorphous biophotonic nanostructures by phase separation. Soft Matter 5, 1792–1795 10.1039/b902775k (doi:10.1039/b902775k) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maia R., Macedo R. H., Shawkey M. D. 2012. Nanostructural self-assembly of iridescent feather barbules through depletion attraction of melanosomes during keratinization. J. R. Soc. Interface 9, 734–743 10.1098/rsif.2011.0456 (doi:10.1098/rsif.2011.0456). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bezdek A., Kuperberg W. 1990. Maximum density space packing with congruent circular cylinders of infinite length. Mathematika 37, 74–80 10.1112/S0025579300012808 (doi:10.1112/S0025579300012808) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marenduzzo D., Finan K., Cook P. R. 2006. The depletion attraction: an underappreciated force driving cellular organization. J. Cell. Biol. 175, 681–686 10.1083/jcb.200609066 (doi:10.1083/jcb.200609066) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baker J. L., Widmer-Cooper A., Toney M. F., Geissler P. L., Alivisatos A. P. 2010. Device-scale perpendicular alignment of colloidal nanorods. Nano Lett 10, 195–201 10.1021/nl903187v (doi:10.1021/nl903187v) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hill G. E. 2006. Female mate choice for ornamental coloration. In Bird coloration: function and evolution, vol. II (eds Hill G., McGraw K.), pp. 137–200 Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johnsgard P. A. 1965. Handbook of waterfowl behavior. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press [Google Scholar]

- 54.Omland K. E. 1996. Female mallard mating preferences for multiple male ornaments 2. Experimental variation. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 39, 361–366 10.1007/s002650050301 (doi:10.1007/s002650050301) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Legagneux P., Théry M., Guillemain M., Gomez D. 2010. Condition dependence of iridescent wing flash-marks in two species of dabbling ducks. Behav. Process 83, 324–330 10.1016/j.beproc.2010.01.017 (doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2010.01.017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ritchie M. G. 2007. Sexual selection and speciation. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 38, 79–102 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.38.091206.095733 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.38.091206.095733) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grant P. R., Grant B. R. 1992. Hybridization of bird species. Science 256, 193–197 10.1126/science.256.5054.193 (doi:10.1126/science.256.5054.193) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Coyne J. A., Orr H. A. 2004. Studying speciation. In Speciation, pp. 1–29 Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wallace A. R. 1912. Darwinism: an exposition of the natural selection with some of its applications. London, UK: Macmillan & Co [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoskin C. J., Higgie M., McDonald K. R., Moritz C. 2005. Reinforcement drives rapid allopatric speciation. Nature 437, 1353–1356 10.1038/nature04004 (doi:10.1038/nature04004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cardoso G. C., Mota P. G. 2008. Speciational evolution of coloration in the genus Carduelis. Evolution 62, 753–762 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00337.x (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00337.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]