Abstract

Magnetic guidance is a physical targeting strategy with the potential to improve the safety and efficacy of a variety of therapeutic agents — including small-molecule pharmaceuticals, proteins, gene vectors, and cells — by enabling their site-specific delivery. The application of magnetic targeting for in-stent restenosis can address the need for safer and more efficient treatment strategies. However, its translation to humans may not be possible without revising the traditional magnetic targeting scheme, which is limited by its inability to selectively guide therapeutic agents to deep localized targets. An alternative two-source strategy can be realized through the use of uniform, deep-penetrating magnetic fields in conjunction with vascular stents included as part of the magnetic setup and the platform for targeted delivery to injured arteries. Studies showing the feasibility of this novel targeting strategy in in-stent restenosis models and considerations in the design of carrier formulations for magnetically guided antirestenotic therapy are discussed in this review.

Keywords: magnetic targeting, biodegradable nanoparticle, drug delivery, gene therapy, vascular disease, stent angioplasty, restenosis

Introduction

Magnetically targeted delivery is a promising experimental strategy for site-specific therapy of vascular disease. In a clinical setting, it can be used as a means to control the biodistribution of therapeutic agents administered in injectable formulations by applying strong, long-range forces created by powerful magnetic fields. Such formulations usually contain submicron-sized, magnetically responsive particles that are put in stable association with a therapeutic agent. These carrier particles are then guided by one or several properly positioned magnetic field sources that help concentrate the therapy in a specific site in the body. This in turn translates into a more efficient treatment with fewer untoward effects. The following review introduces basic principles, promises, and limitations of magnetic targeting as it applies to vascular disease therapy and summarizes recent data showing feasibility of its use in experimental models of in-stent restenosis.

Restenosis Prevention and Treatment — Unmet Needs

Restenosis is a serious complication that stems from arterial injury incurred during vascular intervention procedures aimed at restoring blood flow through obstructed arteries. The introduction of vascular stents — first used only as metallic scaffolds providing mechanical support to the artery, and later redesigned into a platform for site-specific pharmacotherapy (drug eluting stents, DES) for the prevention of intimal hyperplasia and resultant lumen loss — has dramatically reduced the incidence of restenosis in patients with coronary artery disease, improved the outcomes of coronary angioplasty procedures, and substantially reduced reintervention rates.1 However, the long-term safety of their use for coronary artery lesions has not been supported by a number of recent reports,2–5 especially when applied to complex coronary lesions.6 Furthermore, the efficacy of DES in the treatment of occluded peripheral blood vessels has been shown to be suboptimal.7 8 This suggests that the currently used DES may not provide the drug dose and elution kinetics adequate for the noncoronary vasculature, where, unlike in the coronary arteries, restenosis can progress significantly beyond the initial 6-month period.9 10 Notably, reocclusion of arteries implanted with DES presents a formidable therapeutic challenge11 12 and is often approached by repeat stenting (“stent sandwich technique”) in the absence of more effective treatment options. In general, the clinically used DES technology lacks the flexibility necessary for replenishing exhausted drug payload and for allowing specific adjustments of the drug dose and release kinetics to address the disease status of the treated vessel. To fulfill this unmet need, it may be necessary to develop therapeutic approaches that enable more precise control over local drug levels in the stented arteries and can be used as an adjunct or alternative to DES.13

Magnetically guided delivery to stented blood vessels has recently been proposed as a potential clinically viable strategy, and its feasibility for stent-targeted delivery has been shown with different types of pharmaceuticals and cells in animal models of in-stent restenosis.14–16 The aspects of magnetic targeting that make it especially attractive for in-stent restenosis treatment applications are discussed below.

Magnetic Guidance as a Physical Targeting Approach — Promises and Limitations

Magnetically guided delivery is evolving as an experimental targeting strategy with the potential to improve the efficacy and biocompatibility of therapeutic agents by enabling control over their biodistribution. Despite considerable progress made in developing drug candidates with optimized therapeutic profiles, it is still challenging to achieve the pharmacological specificity necessary for providing effective therapy without causing local or systemic toxicity. A concern for adverse reactions — often caused by the same primary mechanisms and occurring within the same dose range as required for the therapeutic effect — can preclude attaining adequate local drug levels in target cells or tissues. This is particularly true for the potent cytotoxic or cytostatic drugs used to treat proliferative conditions, including restenosis and cancer.17–19 This concern has provided a rationale for the design of safer formulations and delivery strategies aimed at extending the therapeutic window, improving efficacy, and minimizing systemic drug exposure.

The use of magnetic guidance as a novel strategy for achieving localized delivery of therapeutic agents to injured blood vessels has been recently explored in several studies.14 15 Magnetic targeting is a physical approach that, like other physical strategies such as ultrasound-assisted drug delivery and brachytherapy, is designed to selectively deliver therapy to spatially defined targets. In this respect, physical targeting methods are distinct from approaches where selectivity is driven by particular chemical or biochemical characteristics of target cells or tissues (e.g., hypoxic or acidic environment, increased expression of certain antigens or enzymes). However, the physical mechanism underlying magnetic targeting makes it unique in its ability to actively concentrate therapeutic agents at their site of action via external guidance, unlike other approaches that do not involve active control over the drug biodistribution but rather rely on site-specific drug retention, localized activation, or release for increasing the target-to-nontarget ratio. Importantly, magnetic guidance can also be applied in combination with strategies using different targeting principles, which may provide additional improvement in the level of target specificity and allow for better control over the initial distribution and local pharmacokinetics of targeted therapeutic agents.

Magnetically targeted delivery systems are traditionally based on two primary components: a magnetically responsive formulation of a therapeutic agent (usually in association with magnetic particles) and a magnetic field source generating a force attracting the particles. The target site needs to be accessible to the magnetic field and the particles applied either locally or systemically, so that their effective magnetic capture and retention can occur in this region. The conceptual simplicity and clinically proven safety of magnetic fields and magnetizable iron oxides configured in injectable particles have prompted a large number of studies showing the feasibility of magnetic guidance in animals and later extended to specific therapeutic applications in humans.20 21 However, the physical mechanism of magnetic targeting also imposes critical limitations on its utility and has made the translation of this approach to a broader range of human applications difficult without making modifications to the traditional targeting scheme as discussed below.

Another challenging aspect in making this approach clinically viable is the design of safe, effective, and scalable magnetic carriers optimized with respect to a particular application and delivery mode and capable of protecting, transporting, and releasing their cargo at the target site without loss of its biological activity. While this requires identification and careful adjustment of multiple variables in the formulation procedure, one of the basic prerequisites for making the formulation both efficient and safe as a magnetic carrier is achieving strong magnetic responsiveness of individual particles in the absence of remanent magnetization (superparamagnetism). The magnetization of the carrier should be fully reversed after removal of a magnetic field in order to prevent magnetically induced particle aggregation and blockage of small blood vessels. An ideal magnetic field source is thus expected to fulfill two tasks: (1) effectively magnetize the particles otherwise possessing no magnetic moment in order to make them responsive to the magnetic force, and (2) create a translational force strong enough to dominate the motion of the magnetized particles and focused at the site of interest. The range within which the source is capable of guiding the motion of magnetizable particles defines the effective capture distance and typically does not exceed several centimeters; this accounts for the discrepancy between the apparent ease of targeted delivery to internal tissues and organs using externally applied magnets in small animals and the difficulty in applying this approach to nonsuperficially located targets in humans.22

Two-Source Targeting Approach as a Platform for Stent Targeted Antirestenotic Therapy

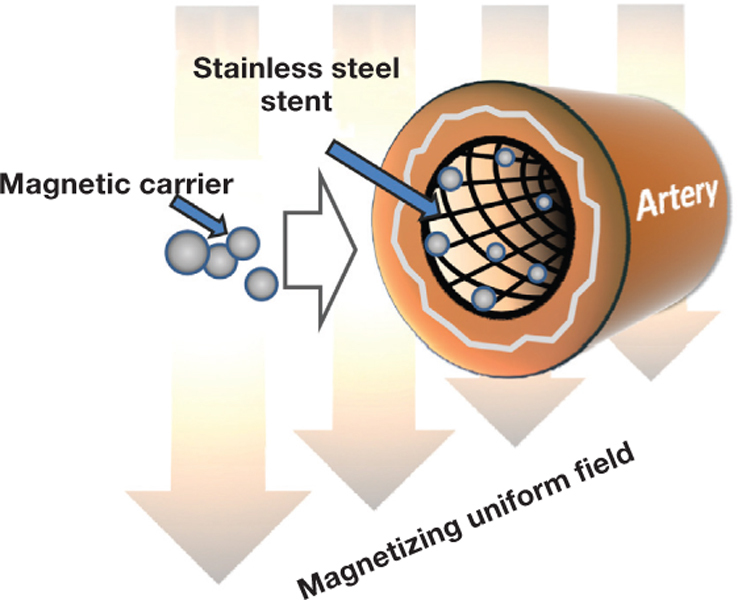

The most fundamental limitation of the traditional magnetic targeting concept based on the use of a single magnetic field source is the inability to focus the magnetic force in a region located at a distance from that source,23 making it inapplicable to deep blood vessels, the target for restenosis therapy. The two above-mentioned tasks of magnetizing the particles and providing the strong driving force focused in the injured arterial segment can, however, be accomplished via a coordinated action of two field sources, each responsible for one of these “assignments”: (1) the primary source providing a strong, uniform, and deep-penetrating magnetizing field, and (2) the secondary (dependent) source positioned in the injured arterial segment and focusing the magnetic force by creating a region of highly localized and strong field nonuniformity (field gradient) (Figure 1).24 25 This theoretical two-source targeting scheme can be realized in clinical practice by using the combination of an MRI scanner or a magnetic navigation system27 as the primary source and a vascular stent made of a reversibly magnetizable alloy as the secondary source. As the magnetizable stent configured in thin intersecting struts becomes “activated” by the strong magnetizing field, this geometry makes it highly efficient in guiding and concentrating the magnetized particles due to extremely strong field gradients in its vicinity.25 In this scenario, the magnetization of the particles and the generation of the magnetic force focused on the stent are achieved simultaneously in a controllable manner and without the use of permanently magnetic materials, thereby addressing the basic safety requirements. The reversibly induced magnetization of stents made of 304-grade stainless steel, while sufficient for providing the basis for the magnetic guidance of locally delivered therapeutic agents to stented arteries,15 16 does not appear to cause adverse effects or changes in the stent structure, position, or function as recently shown in patients who underwent MRI after stent implantation.28 Notably, the design and methods for fabricating clinically acceptable coronary 304 stainless steel stents have been recently described in the literature.29 The feasibility of the two-source magnetic targeting approach first examined theoretically and shown in vitro has recently been demonstrated experimentally in the rat and pig models,14–16 and its potential is currently being explored for a range of therapeutic agents acting on different pharmacological targets in the pathophysiology of in-stent restenosis.

Figure 1.

Arterial targeting of magnetic carriers driven by field gradients induced on a magnetizable stent by a deep-penetrating uniform field. The uniform field simultaneously magnetizes the particles and the stent, confining the particle capture zone to the stented arterial segment. Reproduced from Chorny et al.26

Formulation and Feasibility Studies with Magnetically Targeted Delivery Systems

The design of magnetic carrier formulations and the choice of the formulation method are dependent on the application and the properties of a therapeutic agent. In addition to the magnetic characteristics mentioned above (superparamagnetism and strong magnetization at a practically achievable field strength), general requirements for intravascularly administered particles include lack of toxicity and bioeliminability of the particle components, and a size compatible with parenteral delivery. Considering the dimensions of blood capillaries, the size should be kept below 5 μm, preferably in the nanometer-size range (i.e., nanoparticles). This requirement applies to the entire particle population, suggesting that the particle size distribution should be sufficiently narrow and remain unchanged upon storage and after contact with blood components following their administration. Sterility and isotonicity are also essential requirements that should be considered in the preparation of magnetic nanoparticles (MNP). The particle size of drug-loaded formulations sufficiently magnetically responsive for clinical use is likely to be outside the range <0.2 μm, where sterilization can be readily performed by sterile filtration. In such cases, preparing sterile MNP on a lab or industrial scale may require the use of sterile conditions during all formulation steps.30 Gamma irradiation may be considered as an alternative method if the absence of detrimental effects on the chemical stability of the components and/or colloidal stability of the particles can be demonstrated.31

The release kinetics, another principal determinant of the formulation performance as a targeted delivery vehicle, is dictated by the structure and composition of the magnetic particle, chemical and physical properties of the therapeutic agent, and the mode of its binding to the carrier. To achieve therapeutically adequate efficacy, these variables should be adjusted to provide release corresponding to the time-scale of the pathophysiological process targeted by the specific MNP-based therapeutic approach; however, in all cases the association should be sufficiently stable to ensure that the majority of the cargo remains bound to the carrier before it reaches the site of interest.22 This is not always trivial with small-sized particles and low-molecular-weight drugs, and it may often require the use of chemical modification strategies aimed at increasing the affinity of the drug for the carrier and minimizing its rapid escape into the surrounding medium after administration.17 32 Notably, a therapeutic protein, catalase, exhibited strong affinity for MNP prepared by controlled precipitation of calcium oleate in the presence of nanocrystalline iron oxide, which was key to its successful encapsulation, protracted release in plasma-containing medium, efficient protection from inactivation by proteolytic enzymes, and magnetically enhanced rescuing effect on endothelial cells exposed to hydrogen peroxide in a cell culture model of oxidative stress.30 In other studies, chemical or affinity-based surface attachment strategies were explored for creating stable complexes between MNP and macromolecular biotherapeutics, including proteins, nucleic acids, or viral gene delivery vectors.33–35 The association of replication-deficient adenovirus or plasmid DNA with MNP to form magnetically responsive complexes, via attachment of the vector to the surface of preformed biodegradable polymer-based MNP, was achieved without loss of vector functionality. It also enabled efficient magnetically driven gene transfer in dividing and contact-inhibited cultured vascular cells,34 35 suggesting that the reversible linkage strategy that allows intracellular release of the vector from the complexes can be used to provide magnetically controlled delivery of therapeutic transgenes.

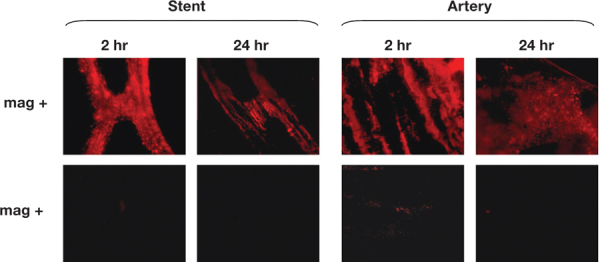

In the absence of additional chemical modifications, highly lipophilic small-molecule pharmaceuticals can exhibit sufficient affinity for MNP formed using biodegradable polyesters, such as polylactide (PLA), in order to provide their efficient entrapment in the polymeric matrix of the particle and release over 48 hours under sink conditions, as recently shown with paclitaxel (PTX).15 Such release kinetics allow the drug to follow the pattern of the magnetically driven localization of MNP to arteries implanted with stents that are reversibly magnetized by a strong uniform field. Differences in arterial levels of MNP between animals treated using the two-source magnetic targeting approach versus nonmagnetic control animals (Figure 2) were paralleled by significantly more pronounced inhibition of in-stent restenosis in magnetically treated animals. Given the time scale of in vitro drug release from MNP in this study, it is plausible that the enhanced intracellular accumulation and retention previously shown for PTX36 contributed to the therapeutic effect of magnetically targeted PTX-loaded MNP observed 2 weeks post surgery.

Figure 2.

In vivo localization and retention of fluorescent MNP targeted (using a 1200 G uniform field) to rat carotid arteries implanted with 304-grade stainless steel stents. A brief 5-minute application of the uniform field resulted in significantly higher local arterial levels of MNP in animals treated under magnetic versus nonmagnetic conditions (upper and lower rows, respectively) 2 hours and 24 hours post treatment. Reproduced from Chorny et al.15

Cells impregnated with MNP represent a unique example of a magnetically responsive formulation where cells play the role of a therapeutic agent, whereas the agent-MNP association is achieved by incorporating MNP in the cell interior. This approach involves complex biological and physical mechanisms, and the efficiency of its performance as a targeted antirestenotic therapy is critically dependent on multiple factors, including (1) the rate of MNP uptake, and (2) intracellular fate of MNP and their effects on cell viability, functionality, and capacity for engraftment and proliferation. While this presents additional challenges in terms of the carrier formulation design, the magnetically targeted cell delivery approach potentially provides a highly potent therapeutic modality in the context of in-stent restenosis treatment, either alone, as a means to achieve enhanced vessel re-endothelialization, or in combination with gene therapeutic strategies via ex vivo genetic cell modification.37 38 Importantly, as recently shown by Kyrtatos et al. on the example of commercially available MNP, special care should be taken to determine for each specific formulation the threshold of magnetic cell loading achievable without significantly compromising cell viability.39 The magnetic responsiveness of cells at this MNP loading level obviously has to be sufficient for scaling up their targeted delivery from small animals to humans using a clinically applicable magnetic setup.39

A recent proof-of-concept study using permanently magnetized stents demonstrated the localization of magnetically loaded endothelial cells to stented coronary and femoral arteries in the pig stenting model 24 hours post procedure.40 The feasibility of the two-source targeting approach for site-specific delivery of endothelial cells was examined in the rat carotid model of in-stent restenosis using reversibly magnetizable 304-grade stainless steel stents and PLA-based MNP designed to provide efficient and rapid cell uptake under magnetic conditions with minimal cell toxicity.16 In the presence of an externally applied magnetizing field (1000 G), MNP-loaded endothelial cells expressing the firefly luciferase reporter and delivered locally or via the aortic arch (with and without a temporary blood flow interruption, respectively) efficiently localized to stented arteries as determined by quantitative bioluminescence measurements 48 hours post procedure. Additional studies focusing on therapeutically relevant endpoints are required to establish the utility and therapeutic efficacy of this approach.

Conclusion

Magnetic targeting is a promising strategy for site-specific delivery of a variety of therapeutic agents. The novel two-source targeting scheme based on controllable magnetization of MNP carriers and vascular stents by deep-penetrating uniform fields provides a viable approach for targeted delivery to injured blood vessels. This may address the principal limitations of the traditional magnetic delivery concept with respect to site-specific vascular therapy and enable effective treatment of in-stent restenosis that still represents a formidable therapeutic challenge.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal Conflict of Interest Statement and none were reported.

Funding/Support: The authors’ research has been supported by grants from the NIH (HL72108), the American Heart Association (Scientist Development Grant 10SDG4020003), the Nanotechnology Institute, the Transdisciplinary Program in Translational Medicine and Therapeutics of the Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics (ITMAT), and the William J. Rashkind Endowment of The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Contributor Information

Michael Chorny, Division of Cardiology Research, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Ilia Fishbein, Division of Cardiology Research, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Richard F. Adamo, Division of Cardiology Research, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Scott P. Forbes, Division of Cardiology Research, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Zoë Folchman-Wagner, Division of Cardiology Research, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Ivan S. Alferiev, Division of Cardiology Research, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

References

- 1.Martin DM, Boyle FJ. Drug-eluting stents for coronary artery disease: a review. Med Eng Phys. 2011 Mar;33(2):148–63. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kabir AM, Selvarajah A, Seifalian AM. How safe and how good are drug-eluting stents? Future Cardiol. 2011 Mar;7(2):251–70.. doi: 10.2217/fca.11.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfisterer M, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Rickenbacher P, Hunziker P, Mueller C, Nietlispach F, et al. Long-term benefit-risk balance of drug-eluting vs. bare-metal stents in daily practice: does stent diameter matter? Three-year follow-up of BASKET. Eur Heart J. 2009 Jan;30(1):16–24. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfisterer ME. Late stent thrombosis after drug-eluting stent implantation for acute myocardial infarction: a new red flag is raised. Circulation. 2008 Sep 9;118(11):1117–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.803627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lagerqvist B, James SK, Stenestrand U, Lindback J, Nilsson T, Wallentin L. Long-term outcomes with drug-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in Sweden. N Engl J Med. 2007 Mar 8;356(10):1009–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harper RW. Drug-eluting coronary stents--a note of caution. Med J Aust. 2007 Mar 5;186(5):253–5. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb00884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duda SH, Bosiers M, Lammer J, Scheinert D, Zeller T, Oliva V, et al. Drug-eluting and bare nitinol stents for the treatment of atherosclerotic lesions in the superficial femoral artery: long-term results from the SIROCCO trial. J Endovasc Ther. 2006 Dec;13(6):701–10. doi: 10.1583/05-1704.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duda SH, Bosiers M, Lammer J, Scheinert D, Zeller T, Tielbeek A, et al. Sirolimus-eluting versus bare nitinol stent for obstructive superficial femoral artery disease: the SIROCCO II trial. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005 Mar;16(3):331–8. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000151260.74519.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Machan L. Clinical experience and applications of drug-eluting stents in the noncoronary vasculature bile duct and esophagus. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006 Jun 3;58(3):447–62. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Umashankar PR, Hari PR, Sreenivasan K. Effect of blood flow on drug release from DES: an experimental study. Int J Cardiol. 2009 Jan 24;131(3):415–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.07.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alfonso F. Treatment of drug-eluting stent restenosis the new pilgrimage: quo vadis? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010 Jun 15;55(24):2717–20.. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aminian A, Kabir T, Eeckhout E. Treatment of drug-eluting stent restenosis: an emerging challenge. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009 Jul 1;74(1):108–16. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma S, Christopoulos C, Kukreja N, Gorog DA. Local drug delivery for percutaneous coronary intervention. Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Mar;129(3):260–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kempe H, Kempe M, Snowball I, Wallén R, Arza CR, Götberg M, et al. The use of magnetite nanoparticles for implant-assisted magnetic drug targeting in thrombolytic therapy. Biomaterials. 2010 Dec;31(36):9499–510. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chorny M, Fishbein I, Yellen BB, Alferiev IS, Bakay M, Ganta S, et al. Targeting stents with local delivery of paclitaxel-loaded magnetic nanoparticles using uniform fields. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 May 4;107(18):8346–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909506107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polyak B, Fishbein I, Chorny M, Alferiev I, Williams D, Yellen B, et al. High field gradient targeting of magnetic nanoparticle-loaded endothelial cells to the surfaces of steel stents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Jan 15;105(2):698–703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708338105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan JM, Zhang L, Tong R, Ghosh D, Gao W, Liao G, et al. Spatiotemporal controlled delivery of nanoparticles to injured vasculature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Feb 2;107(5):2213–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914585107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolodgie FD, John M, Khurana C, Farb A, Wilson PS, Acampado E, et al. Sustained reduction of in-stent neointimal growth with the use of a novel systemic nanoparticle paclitaxel. Circulation. 2002 Sep 3;106(10):1195–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000032141.31476.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vassileva V, Grant J, De Souza R, Allen C, Piquette-Miller M. Novel biocompatible intraperitoneal drug delivery system increases tolerability and therapeutic efficacy of paclitaxel in a human ovarian cancer xenograft model. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007 Nov;60(6):907–14. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0449-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lubbe AS, Bergemann C, Huhnt W, Fricke T, Riess H, Brock JW, et al. Preclinical experiences with magnetic drug targeting: tolerance and efficacy. Cancer Res. 1996 Oct 15;56(20):4694–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lubbe AS, Alexiou C, Bergemann C. Clinical applications of magnetic drug targeting. J Surg Res. 2001 Feb;95(2):200–6. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2000.6030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dobson J. Magnetic nanoparticles for drug delivery. Drug Dev Res. 2006 May 11;67(1):55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grief AD, Richardson G. Mathematical modelling of magnetically targeted drug delivery. J Magn Magn Mater. 2005 Mar 3;293:455–63. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avilés MO, Ebner AD, Ritter JA. Implant assisted-magnetic drug targeting: Comparison of in vitro experiments with theory. J Magn Magn Mater. 2008 Nov;320(21):2704–13. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yellen BB, Forbes ZG, Halverson DS, Fridman G, Barbee KA, Chorny M, et al. Targeted drug delivery to magnetic implants for therapeutic applications. J Magn Magn Mater. 2005 Mar 5; 293:647–54. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chorny M, Fishbein I, Forbes S, Alferiev I. Magnetic nanoparticles for targeted vascular delivery. IUBMB Life. 2011 Aug;63(8):613–20.. doi: 10.1002/iub.479. Epub 2011 Jun 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carpi F, Pappone C. Stereotaxis Niobe magnetic navigation system for endocardial catheter ablation and gastrointestinal capsule endoscopy. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2009 Sep;6(5):487–98. doi: 10.1586/erd.09.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hiramoto JS, Reilly LM, Schneider DB, Skorobogaty H, Rapp J, Chuter TA. The effect of magnetic resonance imaging on stainless-steel Z-stent-based abdominal aortic prosthesis. J Vasc Surg. 2007 Mar;45(3):472–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geller ZE, Albrecht K, Dobranszky J. Electropolishing of coronary stents. Mater Sci Forum. 2008 Jun 17;589:367–72. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chorny M, Hood E, Levy RJ, Muzykantov VR. Endothelial delivery of antioxidant enzymes loaded into non-polymeric magnetic nanoparticles. J Control Release. 2010 Aug 17;146(1):144–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vauthier C, Bouchemal K. Methods for the preparation and manufacture of polymeric nanoparticles. Pharm Res. 2009 May;26(5):1025–58. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9800-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lundberg BB. Preparation and characterization of polymeric pH-sensitive STEALTH(R) nanoparticles for tumor delivery of a lipophilic prodrug of paclitaxel. Int J Pharm. 2011 Apr 15;408(1-2):208–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kempe H, Kates SA, Kempe M. Nanomedicine’s promising therapy: magnetic drug targeting. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2011 May;8(3):291–4. doi: 10.1586/erd.10.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chorny M, Fishbein I, Alferiev I, Levy RJ. Magnetically responsive biodegradable nanoparticles enhance adenoviral gene transfer in cultured smooth muscle and endothelial cells. Mol Pharm. 2009 Sep-Oct;6(5):1380–7. doi: 10.1021/mp900017m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chorny M, Polyak B, Alferiev IS, Walsh K, Friedman G, Levy RJ. Magnetically driven plasmid DNA delivery with biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles. FASEB J. 2007 Aug;21(10):2510–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-8070com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuh HJ, Jang SH, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Computational model of intracellular pharmacokinetics of paclitaxel. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000 Jun;293(3):761–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hofmann A, Wenzel D, Becher UM, Freitag DF, Klein AM, Eberbeck D, et al. Combined targeting of lentiviral vectors and positioning of transduced cells by magnetic nanoparticles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Jan 6;106(1):44–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803746106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fishbein I, Chorny M, Levy RJ. Site-specific gene therapy for cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2010 Mar;13(2):203–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kyrtatos PG, Lehtolainen P, Junemann-Ramirez M, Garcia-Prieto A, Price AN, Martin JF, et al. Magnetic tagging increases delivery of circulating progenitors in vascular injury. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009 Aug;2(8):794–802. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pislaru SV, Harbuzariu A, Gulati R, Witt T, Sandhu NP, Simari RD, et al. Magnetically targeted endothelial cell localization in stented vessels. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Nov 7;48(9):1839–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]