Abstract

The purpose of the current study was to develop and test a method for assessing the effect of outdoor activity context on level of physical activity in preschool children. The Observational System for Recording Physical Activity in Children was used to define the test conditions and various levels of physical activity within a multielement design. In general, all participants were fairly sedentary during the analysis. The fixed playground equipment condition produced the most moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, a finding that does not correspond to the descriptive assessment literature on childhood physical activity.

Keywords: behavioral assessment, functional assessment, obesity, physical activity

Childhood obesity is a significant public health concern in the United States (Ogden et al., 2006), because there are numerous physical and financial problems associated with overweight and obesity in young children (Must et al., 1999; Wolf & Colditz, 1998). The assessment of health-related behaviors is of paramount importance. Information about the predictors of healthy behavior can guide the development of effective interventions to increase such behavior. Physical activity is an important health-related behavior, and it is a good candidate for behavioral assessment because it is easily observable.

Although descriptive assessments of physical activity have been reported and allow the direct observation of potentially valuable information about the contextual events associated with physical activity and the predictors thereof (e.g., Brown et al., 2009; McIver, Brown, Pfeiffer, Dowda, & Pate, 2009), they are inherently limited because they cannot identify the functional relations between the contextual events and physical activity. The identification of variables that evoke or maintain behavior requires the manipulation of the putative controlling variables so that functional relations can be demonstrated rather than inferred. As a starting point, the assessment of environmental contexts that produce the most and least physical activity might provide useful information about the evocative conditions for moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), as well as the contexts in which intervention is most necessary. The purpose of the current study was to assess the effects of environmental context on the level of physical activity in children.

METHOD

Participants and Setting

Two boys and two girls participated. All participants were 4 years old and typically developing. Participants were recruited from a local day care via flyers that were distributed by the day-care operators. Informed consent forms that explained the purposes and procedures of the study were distributed to parents who expressed interest in having their child participate in the study.

Sessions were conducted at the day-care center on a fenced-in outdoor playground, 5 days per week. Only the experimenter and the target child were present on the playground during test and control sessions, and all sessions were video recorded. The local institutional review board approved all aspects of this study.

Response Definition and Measurement

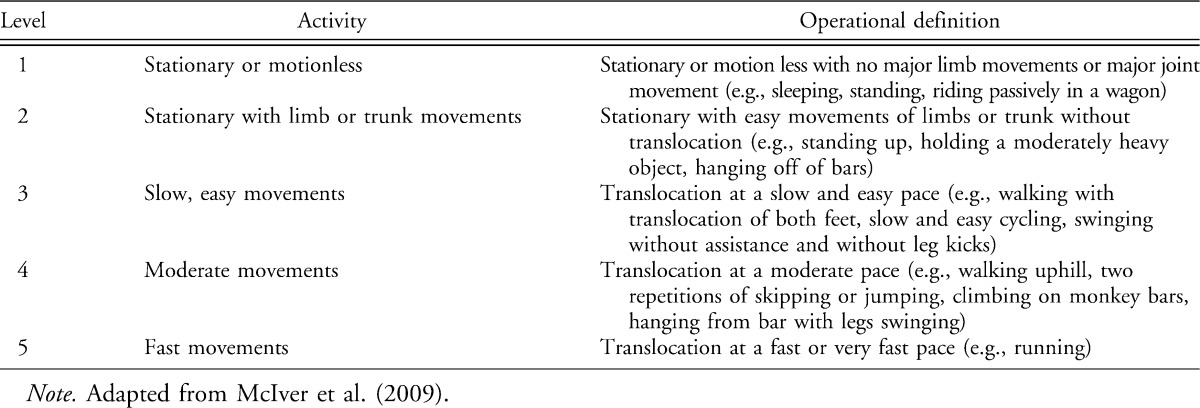

During the initial observation and all subsequent sessions, the Observational System for Recording Physical Activity codes (OSRAC; Brown et al., 2009) were used to assess each participant's level of physical activity (see Table 1). Percentage of intervals with MVPA during each session was calculated by dividing the number of intervals in which the participant engaged in Activity Levels 4 or 5 by the total number of intervals scored. Observers used a continuous 5-s partial-interval recording method in which the highest level of physical activity observed during each interval was recorded. The experimenter did not interact with the participant except to prompt him or her to stay inside the defined session area.

Table 1.

Activity Level Codes

Interobserver Agreement

Interobserver agreement was calculated by dividing the number of agreements on OSRAC activity codes by the number of agreements plus disagreements for each interval and multiplying by 100%. An agreement was defined as both observers scoring an interval as MVPA (i.e., scoring Codes 4 or 5) or both observers scoring the interval as low or no activity (i.e., scoring Codes 1, 2, or 3). Average agreement was 99% for Albert (range, 97% to 100%), 96% for Zack (range, 90% to 100%), 98% for Jessica (range, 90% to 100%), and 98% for Lisa (range, 97% to 100%).

Procedure

A multielement design was used to expose participants to three outdoor activity context conditions that had been previously reported to be most associated with nonsedentary behavior (Brown et al., 2009) and a control condition. Prior to introducing the experimental and control conditions, a brief 30-min naturalistic observation was conducted in which the experimenters collected data on activity level without controlling for any variables (e.g., all contexts were simultaneously available, and all participants were present). The first two 5-min samples in which the participant's entire body was in camera view were coded and served as the baseline levels of physical activity for each participant. Experimental conditions were presented in a randomized order, and replications of each condition were counterbalanced. To control for social events (e.g., adult-arranged activities, prompts, praise) that might influence activity levels independent of the physical environment, participants were alone during all subsequent sessions, and no programmed consequences were provided for any response. Although instructions were provided at the beginning of each experimental condition (see below), they did not seem to alter child behavior from what was observed during the naturalistic baseline sessions. Each session lasted 5 min, with three to five sessions conducted per day. If the participant attempted to leave the session area, he or she was prompted to play only within the designated area.

Outdoor toys

The experimenter guided the participant to the session area where objects used in gross motor activities were present (i.e., two Frisbees, two soft baseballs, one large bouncy ball, one medium bouncy ball, a jump rope, a bucket and shovel, several throwing toys, several orange cones, and a hula hoop). The experimenter directed the participant to “play with the toys” and then stepped away from the session area and activated the video recorder.

Fixed equipment

A jungle gym served as the fixed playground equipment on the day-care playground and was available during this condition. It included two slides, monkey bars, stairs, and several climbing areas. The experimenter directed the participant to “play on the jungle gym” and then stepped away from the session area and activated the video recorder.

Open space

This condition was identical to the previous conditions except that no specific activity materials were present (e.g., balls, objects, or fixed equipment) and the session area was an adjacent area of the playground not used during the previous conditions. The experimenter directed the participant to “play in the grass” and then stepped away from the session area and activated the video recorder.

Control condition

Sessions took place in a small area (3.05 m by 3.05 m) of the playground separate from the areas used in the other conditions. A table and activities that were not anticipated to evoke high levels of physical activity were made available to the participant (e.g., army guys, coloring books, crayons). The experimenter directed the participant to “play at the table” and then stepped away from the session area and activated the video recorder.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

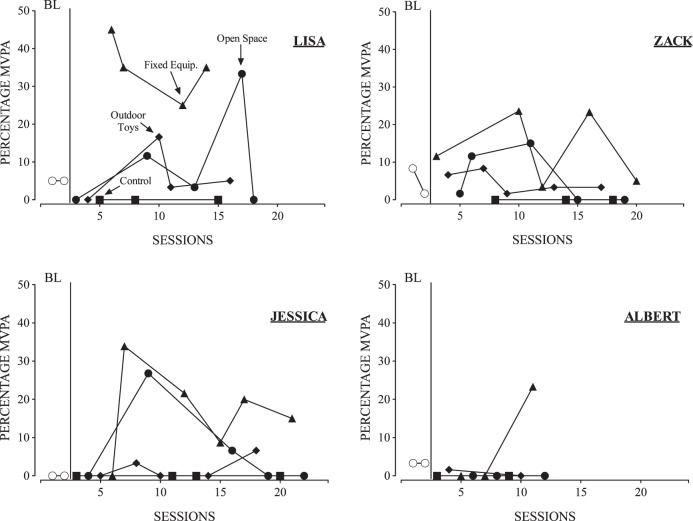

Figure 1 depicts the percentage of intervals in which each participant engaged in MVPA across sessions. For all participants, the fixed-equipment condition produced the most MVPA. However, MVPA occurred in all three experimental conditions but not in the control condition for Lisa, Zack, and Jessica. For Lisa and Jessica, the fixed-equipment condition consistently evoked the highest levels of MVPA, with only a single session during the open-space condition resulting in significant MVPA for each girl. Similarly, for Zack, the fixed-equipment condition produced the most MVPA, except for two sessions during which MVPA fell below the levels observed in the open-space condition. For Albert, MVPA occurred almost exclusively during the last fixed-equipment condition. All participants were engaged with the materials provided for the majority of each session.

Figure 1.

Percentage of intervals with moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per session for all participants.

Because the baseline sessions were naturalistic, we reviewed each session to determine the percentage of 5-s intervals in which each participant was engaged in a particular activity context and in which each participant was alone, with one peer, or with two or more peers. All four participants spent an almost equal amount of time in an open-space context and the outdoor-toys context across both baseline sessions. Only one of the participants (Lisa) played on the fixed equipment during baseline (during 10% of the intervals scored), and none played with the control context materials. Lisa and Jessica were alone during 97% and 100% of intervals, respectively, across both baseline sessions. Zack and Albert spent roughly equal amounts of time playing alone or with one peer, and each were with a larger group during only 3% of the intervals in each baseline session.

Our results suggest that this type of assessment can be used to identify the effects of environmental contexts on the physical activity of children. Such information might be used to individualize interventions for specific children or groups of children. For example, an intervention based on the results of the analysis with these children might involve an arrangement during recess in which reinforcement is provided contingent on engagement with the fixed playground equipment, because the fixed-equipment condition produced the highest rates of MVPA, but the participants almost never played on the fixed equipment during the baseline sessions. However, the degree to which interventions informed by the results of analyses of this type prove to be effective or more effective than current strategies remains to be seen.

It is worth noting that the results of the current study are inconsistent with published research that has employed descriptive assessments of physical activity (e.g., Brown et al., 2009), which suggests that contexts that include fixed equipment produce lower levels of MVPA than outdoor toys and open space. The lack of correspondence between descriptive analyses and experimental analyses of problem behavior has been reported in the literature (e.g., Pence, Roscoe, Bourret, & Ahearn, 2009), but a direct comparison of physical activity assessment methods is needed before any firm conclusions can be drawn.

Several limitations of this study also warrant mention. First, only three outdoor activity contexts were evaluated, because previous descriptive research indicated that these activity contexts were the best predictors of MVPA in preschool children. A more comprehensive analysis would assess activity levels in multiple activity contexts. Also, it is likely that the addition of peers or adults in certain contexts might alter the amount of MVPA observed under those conditions. Second, consequences were not manipulated during the analysis. For an analysis of physical contexts that support high levels of physical activity, this is not problematic. However, for a comprehensive functional analysis of behavior, all relevant terms of the behavioral contingency should be manipulated. Third, the clinical utility of this type of analysis is unknown without corresponding treatment evaluations. The functional analysis of physical activity is a clinically viable tool only if it is able to inform effective interventions.

Given the prevalence of and continued increase in children's obesity rates, effective prevention and treatment strategies are needed. The development of methods to assess experimentally the environmental variables that influence physical activity has the potential to improve our understanding of the stimuli that evoke and maintain physical activity and thereby lead to the development of more individualized and potentially more effective interventions for improving health and well-being. The methodology reported here might be a useful starting point toward this end.

Acknowledgments

This study is based on a thesis submitted by the first author in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the MA degree at the University of the Pacific. We thank Barbara Beavers of Garden of Eden day care for her assistance and cooperation. We also thank Carolynn Kohn and Darrin Kitchen for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Brown W.H, Pfeiffer K.A, McIver K.L, Dowda M, Addy C.L, Pate R.R. Social and environmental factors associated with preschoolers' nonsedentary physical activity. Child Development. 2009;80:45–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIver K.L, Brown W.H, Pfeiffer K.A, Dowda M, Pate R.R. Assessing children's physical activity in their homes: The observational system for recording physical activity in children—home. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42:1–16. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Must A, Spandano J, Coakley E.H, Field A.E, Colditz G, Dietz W.H. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:1523–1630. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden C.L, Carroll M.D, Curtin L.R, McDowell M.A, Tabak C.J, Flegal K.M. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence S.T, Roscoe E.M, Bourret J.M, Ahearn W.H. Relative contributions of three descriptive methods: Implications for behavioral assessment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42:425–446. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf A.M, Colditz G.A. Current estimates of the economic cost of obesity in the United States. Obesity Research. 1998;6:97–106. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1998.tb00322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]