Abstract

Phytic acid (PA) is the storage form of phosphorus (P) in seeds and plays an important role in the nutritional quality of food crops. There is little information on the genetics of seed and seedling PA in mungbean [Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek]. Quantitative trait loci (QTL) were identified for phytic acid P (PAP), total P (TP), and inorganic P (IP) in mungbean seeds and seedlings, and for flowering, maturity and seed weight, in an F2 population developed from a cross between low PAP cultivated mungbean (V1725BG) and high PAP wild mungbean (AusTRCF321925). Seven QTLs were detected for P compounds in seed; two for PAP, four for IP and one for TP. Six QTLs were identified for P compounds in seedling; three for PAP, two for TP and one for IP. Only one QTL co-localized between P compounds in seed and seedling suggesting that low PAP seed and low PAP seedling must be selected for at different QTLs. Seed PAP and TP were positively correlated with days to flowering and maturity, indicating the importance of plant phenology to seed P content.

Keywords: mungbean, Vigna radiata, phosphorus, phytic acid, QTL, SSR

Introduction

Phytic acid (PA; myo-inositol-1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6- hexaphosphate), is the storage form of P in seeds of cereals and legumes (Lott et al. 2000). Dietary PA inhibits the absorption of protein and certain mineral nutrients. It is not efficiently digested by human and nonruminant animals such as swine, poultry and fish. Seed-derived dietary PA can contribute to human mineral deficiencies. When PA is consumed as feeds, monogastric animals excrete a large fraction of phytate salts, which can contribute to water pollution (Sharpley et al. 1994).

Breeding for low PA (lpa) crops has recently been considered as a potential way to increase nutritional quality of crop products. Approaches include use of low phytic acid alleles (Cichy and Raboy 2008), genetic engineering (Shi et al. 2007) and QTL mapping for loci that impact seed P and PA (Blair et al. 2009, Cichy et al. 2009). Mungbean (Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek) is an important food legume crop of Asia. Its seeds and flour are used in various foods. Another main use of mungbean is to be consumed as vegetable in the form of sprouts, either cooked or raw sprouts. To date in mungbean only naturally occurring germplasm that possesses low PA have been identified (Sompong et al. 2010). They reported that the high PA is controlled by dominant alleles at two independent loci showing duplicated recessive epistasis. In this paper, we report the first QTL mapping for PA and P contents in seed and seedling of mungbean.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and DNA extraction

A mapping population of F2 plants was developed from a cross between a high seed PA, V1725BG (as female) and a low seed PA, AusTRCF321925 (as male). V1725BG is a cultivated mungbean from Iran, while AusTRCF321925 is a wild mungbean from Australia. One hundred and seventy F2:3 lines together with the parents were grown in an experimental field without replication at Kasetsart University, Kamphaeng Saen, Nakhon Pathom, Thailand during March–May, 2009. Each F2:3 lines had at least 10 plants. F4 seeds of each line were harvested in bulk and used for phenotypic measurement. DNA was extracted from young leaves of the F2 plants and their parents using the method described by Lodhi et al. (1994) with a modification that absolute ethanol was used instead of 95% ethanol.

PAP, TP and IP assay in seed and seedling

F4 seeds from 10–20 plants in each F2:3 line were bulked and divided into two parts. The first part was prepared for seed P determination and the second part was germinated on wet tissue papers at room temperature and watered daily for 3 days. The seeds and seedlings were dried at 60°C for 72 hr, milled to pass through a 40 mesh (0.5 mm) screen and stored in desiccators. The samples were separated into three parts, each for analysis of PAP, TP and IP with three determinations per part.

Determination of Seed and Seedling P Constituents

PAP content was assayed in seed via a modification of the methods as described (Haug and Lantzsch 1983). Fifty mg of ground seed or seedling were assayed in triplicate and sample PAP was calculated via comparison with PAP standard curves (0.0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50 and 75 μg PAP), prepared using reagent-grade PAP (Sigma Chem.). PAP can be converted to PA by multiplying by 3.548. To determine TP content, 50 mg of the ground seed or seedling was placed into a 15 mL tube, to which 1.0 mL of concentrated H2SO4 was added, and wet-digested to completion. P was then determined colorimetrically using a modification of the method of Chen et al. (1956). TP was calculated using the standard curve of KH2PO4 (0.0, 155, 465, 930 and 1395 ng P). IP content was assayed using a modification of the method as described (Raboy et al. 1984) and IP content calculated via comparison with the same standard curve as determination of TP content.

Evaluation of agronomic traits

Days to flowering, days to maturity and seed size were measured in the F2:3 lines. Days to flowering and days to maturity were recorded when 50% of the plants in the family reached the stage. Seed size was measured by weighing 100-seed sample.

SSR marker analysis

A total of 991 SSR primers were used to screen for polymorphism between the parents. Five hundred and forty-six primers were developed from mungbean (Gwag et al. 2006, Seehalak et al. 2009, Somta et al. 2008, 2009, Thangphatsornruang et al. 2009), 142 were from azuki bean (Wang et al. 2004), 189 were from cowpea (Kongjaimun et al., unpublished data, Li et al. 2001), and 114 were from common bean (Benchimol et al. 2007, Blair et al. 2009, Buso et al. 2006, Gaitán-Solís et al. 2002, Guerra-Sanz 2004). The polymorphic markers were used to analyze the F2 population. PCR was carried out following Somta et al. (2008) with the exception that annealing temperature varied from 47 to 65°C, depending on primers. The PCR products were separated on 5% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and visualized by silver staining.

Data analysis and QTL mapping

Correlation among traits at 0.05 probability level was determined by Pearson correlation coefficient analysis using software R-2.10.0 (R Development Core Team 2008). The genetic linkage map was constructed using JoinMap 3.0 software (van Ooijen and Voorips 2001). Chi-square tests for goodness of fit to the expected segregation ratio of 1:2:1 were determined for each SSR marker. The minimum LOD threshold of 8.0 and recombination frequency of 0.50 were used to assign markers into linkage groups. Recombination frequency was converted to genetic distance (cM) by Kosambi’s mapping function.

QTL analysis was performed with the Windows QTL Cartographer 2.5 software (Wang et al. 2007) using composite interval mapping (CIM) method, model 6 (forward and backward regression) with window size of 10 cM, background markers of 5 and 1-cM walkspeed. Significant LOD score threshold at 0.05 probability level was determined to identify the QTL by running a 1,000 permutation tests. Linkage groups were named following azuki bean linkage groups (Han et al. 2005). QTLs were named following Somta et al. (2006).

Results

Variation in P compound contents and agronomic traits

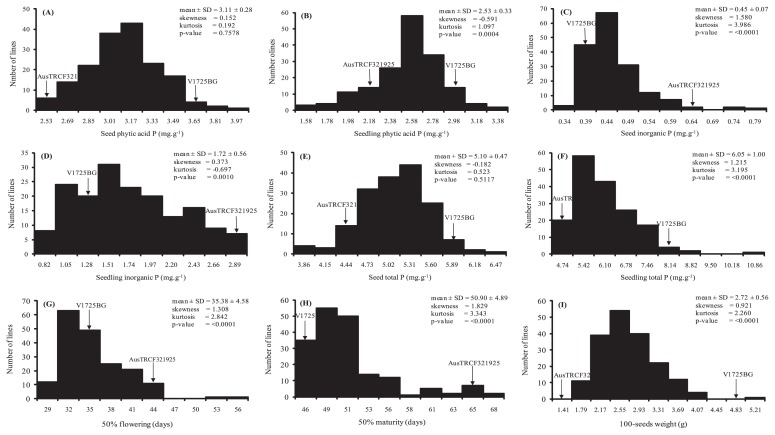

Statistically significant variation between the parents and among the F2:3 families were observed for all traits (Supplemental Table 1). Observed continuous distribution in the F2 population indicates that these traits are inherited in a quantitative fashion (Fig. 1). TP and PAP in seed were normally distributed while the distributions of the other traits were skewed. Transgressive segregation was observed for PAP, IP and TP in both seed and seedling, revealing that both V1725BG and AusTRCF321925 contributed a combination of alleles that were either positive or negative for the traits.

Fig. 1.

Frequency distribution in F2:3 population from the cross V1725BG × AusTRCF321925, for (a) phytic acid P in seed, (b) phytic acid P in seedling, (c) inorganic P in seed, (d) inorganic P in seedling, (e) total P in seed, (f) total P in seedling, (g) days to 50% flowering, (h) days to 50% maturity and (i) 100-seed weight.

Seed weight was not correlated with any of the three seed P fractions (Table 1). Therefore variation in these seed P fractions among the parents and F2:3 progenies was not an artifact of the large difference in seed size between the parents or variation for seed weight in the F2:3 progeny. With the exception of seed weight, both seed and seedling TP and PAP were positively correlated with nearly all other seed, seedling and agronomic traits. In contrast, seed IP was only correlated with seed and seedling TP. Seedling IP was positively correlated with seedling TP, seed TP and PA, days to flowering and maturity, but negatively correlated with seed weight. Seedling PAP was positively correlated with seed TP and PAP, seedling TP and seed weight.

Table 1.

Correlations among phytic acid P (PAP), inorganic P (IP) and total P (TP) in seed (SD) and seedling (SL); days to 50% flowering (DFL), days to 50% maturity (DMT), and 100-seed weight (SD100WT) in the population of 170 F2:3 families from the cross V1725BG × AusTRCF321925

| SDPAP | SLPAP | SDIP | SLIP | SDTP | SLTP | DFL | DMT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLPAP | 0.321*** | |||||||

| SDIP | 0.0802 | 0.0021 | ||||||

| SLIP | 0.199** | −0.0301 | 0.0515 | |||||

| SDTP | 0.534*** | 0.273*** | 0.181* | 0.386*** | ||||

| SLTP | 0.303*** | 0.298*** | 0.188* | 0.647*** | 0.518*** | |||

| DFL | 0.279** | 0.0345 | 0.0525 | 0.210** | 0.219** | 0.300** | ||

| DMT | 0.297** | 0.0395 | 0.0751 | 0.184* | 0.230** | 0.282** | 0.762** | |

| SD100WT | −0.0533 | 0.201** | 0.0590 | −0.223** | −0.1420 | −0.0858 | −0.0564 | −0.0186 |

are significant at 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001 probability level, respectively.

Linkage map construction

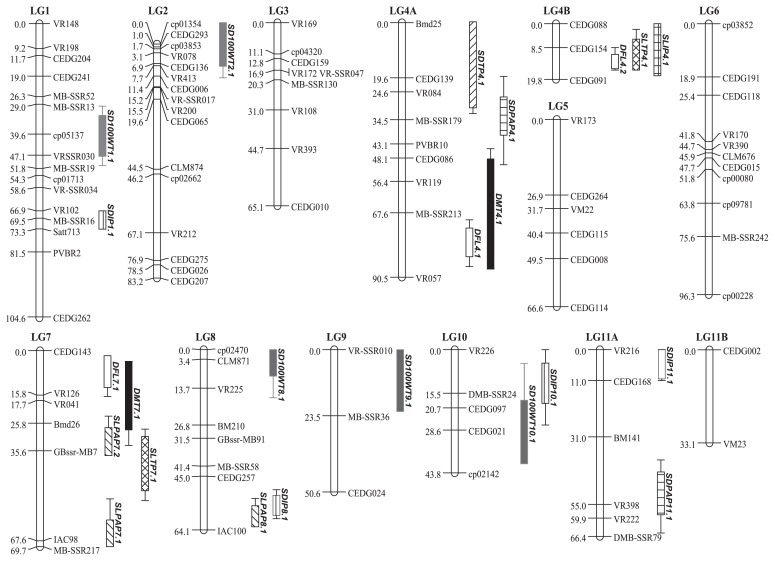

A total of 101 SSR markers detected polymorphisms between the parents and were used in the construction of linkage map (Supplemental Table 2). The map consisted of 13 linkage groups (LGs) and spanned a total length of 855.8 cM (Fig. 2). The length of the LGs ranged from 19.8 (LG04B) to 104.6 cM (LG01). The number of markers per LG ranged from 2 (LG 11B) to 16 (LG 1). The average distance between the adjacent markers varied from 5.5 to 33.1 cM. LG09 and LG11B showed gaps wider than 20 cM.

Fig. 2.

An SSR-based linkage map constructed from an F2 population from the cross V1725BG × AusTRCF321925 and genomic regions associated with phytic acid P (PAP), inorganic P (IP) and total P (TP) in seed (SD) and seedling (SL), days to 50% flowering (DFL), days to 50% maturity (DMT) and seed weight (SD100WT).

QTL identification

In total, 23 QTLs were found associated with the nine traits (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Two, four and one QTLs distributed on five linkage groups were found for seed PAP, IP and TP, respectively. The phenotypic variance explained (PVE) by these QTLs ranged from 3.43% to 11.24% of the trait variation. At QTLs SDIP1.1, SDIP8.1 and SDIP11.1, the alleles from AusTRCF321925 decreased trait values. QTLs SDPAP4.1 and SDTP4.1 overlapped.

Table 2.

QTLs detected for phytic acid P (PAP), inorganic P (IP) and total P (TP) in seed (SD) and seedling (SL); days to 50% flowering (DFL), days to 50% maturity (DMT), and 100-seed weight (SD100WT). The mapping population is F2:3 families derived from V1725BG × AusTRCF321925

| Trait | QTL | Linkage group | Interval markers | LOD | %PVEa from regression | Additive effectb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Single | Multiple | ||||||

| Seed PAP | SDPAP4.1 | 4A | CEDG139-MB-SSR179 | 3.78 | 11.24 | 14.39 | 0.0406 |

| SDPAP11.1 | 11A | BM141-VR222 | 4.00 | 6.06 | 0.0670 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Seed IP | SDIP1.1 | 1 | Satt713-VR102 | 4.33 | 5.25 | 16.97 | −0.0333 |

| SDIP8.1 | 8 | CEDG257-IAC100 | 7.20 | 3.43 | 0.0737 | ||

| SDIP10.1 | 10 | VR226-CEDG097 | 3.45 | 5.59 | −0.0006 | ||

| sSDIP11.1 | 11A | VR216-CEDG168 | 2.96 | 5.54 | 0.0285 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Seed TP | SDTP4.1 | 4A | Bmd25-MB-SSR179 | 2.64 | 10.58 | 0.1349 | |

|

| |||||||

| Seedling PAP | SLPAP7.1 | 7 | MB-SSR217-GBssr-MB7 | 5.35 | 7.56 | 8.11 | −0.3350 |

| SLPAP7.2 | 7 | IAC98-Bmd26 | 4.13 | 7.57 | 0.1458 | ||

| SLPAP8.1 | 8 | MB58-IAC100 | 3.66 | 1.38 | −0.5518 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Seedling IP | SLPAP4.1 | 4B | CEDG088-CEDG091 | 2.65 | 7.49 | −0.2413 | |

|

| |||||||

| Seedling TP | SLTP4.1 | 4B | CEDG088-CEDG091 | 5.65 | 13.82 | 21.16 | −0.5252 |

| SLTP7.1 | 7 | IAC98-Bmd26 | 4.62 | 6.59 | 0.9745 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Days to 50% flowering | DFL4.1 | 4A | MB213-VR057 | 5.77 | 33.38 | 37.89 | 6.0000 |

| DFL4.2 | 4B | CEDG154-CEDG091 | 8.35 | 25.70 | −1.3533 | ||

| DFL7.1 | 7 | VR126-CEDG143 | 4.43 | 5.01 | −0.8575 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Days to 50% maturity | DMT4.1 | 4A | CEDG086-VR057 | 4.89 | 25.67 | 29.47 | 4.3978 |

| DMT7.1 | 7 | GBssr-MB7-CEDG143 | 2.64 | 7.24 | −1.2200 | ||

|

| |||||||

| 100-Seed weight | SD100WT1.1 | 1 | CP1713-CP5137 | 6.52 | 18.41 | 48.03 | −0.1465 |

| SD100WT2.1 | 2 | VR078-CEDG136 | 2.60 | 6.80 | −0.0618 | ||

| SD100WT8.1 | 8 | CP2470-CLM871 | 2.51 | 11.70 | −0.1873 | ||

| SD100WT9.1 | 9 | VRSSR010-MB36 | 2.90 | 17.88 | −0.2141 | ||

| SD100WT10.1 | 10 | CEDG097-CP2142 | 3.02 | 12.38 | −0.2313 | ||

PVE is phenotypic variance explain.

Additive gene effect; where positive values indicate allelic contribution from the cultivated accession V1725BG and negative values from the wild accession AusTRCF321925

For seedling P fraction QTLs, three were detected for PAP, while two and one were identified for TP and IP, respectively (Table 2 and Fig. 2). These QTLs were located on three linkage groups. Alleles of AusTRCF321925 at QTLs SLPAP7.1, SLPAP8.1 and SLTP4.1 reduced the value of the respective P compounds. QTLs SLIP4.1 and SLTP4.1 were co-localized to the marker interval CEDG088-CEDG091, whereas QTLs SLPAP7.2 and SLTP7.1 both mapped between IAC98 and Bmd26. Among the six QTLs identified for seedling P fractions, only one (SLPAP8.1) co-localized with a QTL for a seed P fraction (SDIP8.1) (Fig. 2). Three QTLs for days to flowering and two for days to maturity were detected, while five QTLs were identified for seed weight (Table 2 and Fig. 2). PVE of the QTLs for days to flowering ranged from 5.01% to 33.38%, wherase those of days to harvesting varied from 7.24% to 25.67%. The PVE of the QTLs for seed weight were between 6.83% and 18.41%. Location of the QTLs DFL4.1 and DMT4.1 and DFL7.1 and DMT7.1 overlapped.

On LG 4, the maturity QTL overlapped with the seed PA QTL. This agrees with their statistically-significant correlation (Table 1). Of these major QTLs, the cultivated parent V1725BG provided the alleles for increased seed PA, as well as days to maturity. At these QTLs, alleles from V1725BG increased seedling PA, but decreased days to flowering and days to maturity.

Discussion

Continuous distribution for PAP, IP and TP in both seed and seedling of the F2 population illustrates the quantitative component of these traits. Similarly, quantitative variation in seed PA and TP was observed in soybean (Raboy et al. 1984) and common bean (Blair et al. 2009, Cichy et al. 2009). The positive correlation between seed TP and PA concentrations observed here has been reported in studies of mungbean (Sompong et al. 2007), soybean (Raboy et al. 1984) and common bean (Blair et al. 2009). The typically highly positive correlation between seed TP and PAP can be attributed to the role of PAP as the storage form of P in seeds.

Variation in mineral concentrations in plant or seed tissues can be an outcome of agronomic traits such as yield, days to maturity and seed weight, and therefore these relationships must be evaluated in all QTL mapping populations (White and Broadley 2005). In a study of the variation in mineral composition in common bean cultivars, Moraghan and Grafton (2001) reported positive correlations between seed weight and seed TP. In a QTL mapping study of the model legume Medicago truncatula, Sankaran et al. (2009) similarly reported a positive correlation between seed weight and seed total P, but negative correlations between seed weight and seed Ca, Cu and Zn. The present study provides a good test of the relationship between seed weight and P content in that the mapping population parents differed greatly in seed weight and seed weight varied greatly in the F2:3 population (Supplemental Table 1). In the present study, the lack of significant positive correlations between seed weight and seed constituents and the non-linkage of their QTLs indicate that selection for low seed P and PA and seedling PA can be expected to have no effect on seed size. A similar conclusion was reported in common bean (Blair et al. 2009). The positive correlations between seed P fractions and both days to flowering and days to maturity observed in the present study confirm that agronomic traits such as plant phenology must also be considered when dissecting the genetics of seed mineral content.

In conclusion, the present study identified a few mungbean QTLs with low or moderate effect on PA and TP contents in seed and seedling. However, some QTLs for PA and TP contents of seed and seedling overlapped with QTLs for seed size, flowering and maturity, indicating that care must be taken in applying such results in a plant breeding program.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported to U. Sompong by a scholarship from the Royal Golden Jubilee Ph.D. Program of the Thailand Research Fund. P. Srinives and P. Somta acknowledged the support from Thailand’s National Science and Technology Development Agency. We thank Center for Agricultural Biotechnology, Kasetsart University for Lab Facility. We would like to thank the scientific and administrative staff of the USDA-ARS Aberdeen, Idaho laboratories for their kind assistance during Dr. Sompong’s visit while working on this project.

Literature Cited

- Benchimol L.L., de Campos T., Carbonell S.A.M., Colombo C.A., Chioratto A.F., Formighieri E.F., Gouvea L.R.L., de Souza A.P. (2007) Structure of genetic diversity among common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) varieties of Mesoamerican and Andean origins using new developed microsatellite markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 54: 1747–1762 [Google Scholar]

- Blair M.W., Sandoval T.A., Caldas G.V., Beebe S.E., Paez M.I. (2009) Quantitative trait locus analysis of seed phosphorus and seed phytate content in a recombinant inbred line population of common bean. Crop Sci. 49: 237–246 [Google Scholar]

- Buso G.S.C., Amaral Z.P.S., Brondani R.P.V., Ferreira M.E. (2006) Microsatellite markers for the common bean Phaseolus vulgaris.Mol. Ecol. Notes 6: 252–254 [Google Scholar]

- Chen P.S., Toribara I.T.Y., Warner H. (1956) Micro determination of phosphorus. Anal. Chem. 28: 1756–1758 [Google Scholar]

- Cichy K.A., Raboy V. (2008) Evaluation and Development of Low Phytate Crops. In: Krishnan, H. (ed.) Modification of Seed Composition to Promote Health and Nutrition, Agronomy Monograph Series, American Society of Agronomy and Crop Science Society of America, pp. 177–200 [Google Scholar]

- Cichy K.A., Caldas G.V., Snapp S.S., Blair M.W. (2009) QTL analysis of seed iron, zinc, and phosphorus levels in an Andean bean population. Crop Sci. 49: 1742–1750 [Google Scholar]

- Gaitán-Solís E., Duque M.C., Edwards K.J., Tohme J. (2002) Microsatellite repeats in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris): isolation, characterization, and cross-species amplification in Phaseolus ssp. Crop Sci. 42: 2128–2136 [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Sanz J.M. (2004) New SSR markers of Phaseolus vulgaris from sequence databases. Plant Breed. 123: 87–89 [Google Scholar]

- Gwag J.G., Chung W.K., Chung H.K., Lee J.H., Ma K.H., Dixit A., Park Y.J., Cho E.G., Kim T.S., Lee S.H. (2006) Characterization of new microsatellite markers in mungbean, Vigna radiata (L.). Mol. Ecol. Notes 6: 1132–1134 [Google Scholar]

- Han O.K., Kaga A., Isemura T., Wang X.W., Tomooka N., Vaughan D.A. (2005) A genetic linkage map for azuki bean (Vigna angularis (Willd.) Ohwi & Ohashi). Theor. Appl. Genet. 111: 1278–1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug W., Lantzsch H.I. (1983) A sensitive method for rapid determination of phytate in cereals and cereal products. J. Sci. Food Agric. 34: 1423–1426 [Google Scholar]

- Li C.D., Fatokun C.A., Ubi B., Singh B.B., Scoles G.J. (2001) Determining genetic similarities and relationships among cowpea breeding lines and cultivars by microsatellite markers. Crop Sci. 41: 189–197 [Google Scholar]

- Lodhi M.A., Ye G.N., Weeden N.F., Reisch B.I. (1994) A simple and efficient method for DNA extraction from grapevine cultivars and Vitis species. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 12: 6–13 [Google Scholar]

- Lott J.N.A., Ockenden I., Raboy V., Batten G.D. (2000) Phytic acid and phosphorus in crop seeds and fruits: global estimate. Seed Sci. Res. 10: 11–33 [Google Scholar]

- Moraghan J.T., Grafton K. (2001) Genetic diversity and mineral composition of common bean seed. J. Sci. Food Agric. 81: 404–408 [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team(2008) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: ISBN:3-900051-07-0 http://R-project.org [Google Scholar]

- Raboy V., Dickinson D.B., Below F.E. (1984) Variation in seed total phosphorus, phytic acid, zinc, calcium, magnesium, and protein among lines of Glycine max and G. soja. Crop Sci. 24: 431–434 [Google Scholar]

- Sankaran R.P., Huguet T., Grusak M.A. (2009) Identification of QTL affecting seed mineral concentrations and content in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Theor. Appl. Genet. 119: 241–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seehalak W., Somta P., Musch W., Srinives P. (2009) Microsatellite markers for mungbean developed from sequence database. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 9: 862–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley A.N., Charpa S.C., Wedepohl R., Sims J.Y., Daniel T.C., Reddy K.R. (1994) Managing agricultural phosphorus for protection of surface waters: issues and options. J. Environ. Qual. 23: 437–451 [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Wang H., Schellin K., Li B., Faller M., Stoop J.M., Meeley R.B., Ertl D.S., Ranch J.P., Glassman K. (2007) Embryo-specific silencing of a transporter reduces phytic acid content of maize and soybean seeds. Nature Biotech. 25: 930–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sompong U., Nakasathien S., Kaewprasit C., Srinives P. (2007) Variation in phytic acid content in seed and correlation with agronomic traits of mungbean (Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek). Agri. Sci. J. 38: 243–250 [Google Scholar]

- Sompong U., Nakasathien S., Kaewprasit C., Srinives P. (2010) Inheritance of seed phytate in mungbean (Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek). Euphytica 171: 389–396 [Google Scholar]

- Somta P., Kaga A., Tomooka N., Kashiwaba K., Isemura T., Chaitieng B., Srinives P., Vaughan D.A. (2006) Development of an interspecific Vigna linkage map between Vigna umbellata (Thunb.) Ohwi & Ohashi and V. nakashimae (Ohwi) Ohwi & Ohashi and its use in analysis of bruchid resistance and comparative genomics. Plant Breed. 125: 77–84 [Google Scholar]

- Somta P., Musch W., Kongsamai B., Chanprame S., Nakasathien S., Toojinda T., Sorajjapinun W., Seehaluk W., Tragoonrung S., Srinives P. (2008) New microsatellite markers isolated from mungbean (Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek). Mol. Ecol. Resour. 8: 1155–1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somta P., Seehalak W., Srinives P. (2009) Development, characterization and cross-species amplification of mungbean (Vigna radiata) genic microsatellite markers. Conserv. Genet. 10: 1939–1943 [Google Scholar]

- Thangphatsornruang S., Somta P., Uthaipaisanwong P., Chanprasert J., Sangsrakru D., Seehalak W., Sommanas W., Tragoonrung S., Srinives P. (2009) Characterization of microsatellites and gene contents from genome shotgun sequences of mungbean (Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek). BMC Plant Biol. 9: 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ooijen J.W., Voorips R.E. (2001) JoinMap®3.0: software for the calculation of genetic linkage maps. Plant Research International, Wageningen [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Basten C.J., Zeng Z.B. (2007) Window QTL Cartographer 2.5. Department of Statistics, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA: http://statgen.ncsu.edu/qtlcart/WQTLCart.htm [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.W., Kaga A., Tomooka N., Vaughan D.A. (2004) The development of SSR markers by a new method in plants and their application to gene flow studies in azuki bean [Vigna angularis (Willd.) Ohwi and Ohashi]. Theor. Appl. Genet. 109: 352–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White P.J., Broadley M.R. (2005) Biofortifying crops with essential mineral elements. Trends Plant Sci. 10: 586–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.