Abstract

Five physiological and eleven yield traits of two pairs of sister lines generated from a high generation with similar genetic background (SLs) for purple pericarp were investigated to explore the reasons behind low-yield production of colored rice. Of the five physiological traits examined, except grain anthocyanin content, there were generally similar trends between the P (purple-pericarp) lines and the corresponding W (white-pericarp) lines over two seasons (in the year 2009 and 2010 separately). The results demonstrated that the chlorophyll content of flag leaves, the net photosynthetic rate of flag leaves, and the grain anthocyanin content could be easily influenced by the environment. The physiological functions of the traits for the P lines were more active than those of the corresponding W lines in the year 2010. The grain anthocyanin content of the P lines was much greater in the year 2010 than in the year 2009 during the growth period. The investigation of yield traits revealed that the P lines had reduced 1000-grain weight, yield per plot and grain/brown rice thickness compared to the W lines. A difference comparison of these traits and a source-sink and transportation relationship analysis for these SLs suggested that small sink size was a key reason behind yield reduction of purple pericarp rice.

Keywords: rice (Oryza sativa L.), purple pericarp, SLs (sister lines generated from a high generation with similar genetic background), 1000-grain weight, anthocyanin

Introduction

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is an important staple food crop throughout the world. Colored rice refers to purple- or red-grained rice and this coloration is the result of accumulated anthocyanins in the pericarp. The pericarp not only contains abundant nutritional components and physiologically active compounds, but is also rich in edible pigments that are important for food manufacturing industry. For example, anthocyanin pigments from purple pericarp rice have been evaluated as natural and functional colorants for foods.

Anthocyanins have been recognized as health-enhancing substances due to their antioxidant activity (Nam et al. 2006, Satue-Gracia et al. 1997), anti-inflammatory (Tsuda et al. 2002), anticancer (Hyun and Chung 2004, Kamei et al. 1995, Zhao et al. 2004) and hypoglycemic activities (Tsuda et al. 2003). In the pursuit of a healthy diet, many people in China add purple rice to their meals when cooking. However, compared with conventional rice, the yield of the colored rice varieties is much lower (Liu et al. 1998, Peng et al. 2004, Zhang et al. 1994), and farmers are often not willing to plant colored rice because of its low yield. Consequently, colored rice production does not meet its consumption and the demands of the rice market. Therefore, the reasons behind the reduced yield of colored rice need to be determined.

Low yield are common in the production of colored rice. Some researchers have focused on environment effects on yield variations of colored rice (Cai 2001a, 2001b, 2002, He et al. 1997, Wang and Guo 1994, Zhang et al. 1994). Other reports focused on the traits of colored rice that were associated with its reduced yield. For example, a comparison of the agronomic traits between purple pericarp rice and hybrid rice found that the distribution of photosynthates in purple-pericarp rice was not consonant and that there were fewer photosynthates to the yield organs, a lower sink capacity of the spikelets, and a lower seed setting rate in the purple rice than in the hybrid rice (Xie et al. 2001). Zhou et al. (2004) proposed a hypothesis that the pigments in colored rice may cause a decrease of chlorophyll content, which could ultimately lead to the reduced yield.

Most rice yield traits are quantitative traits that are controlled by multiple genes, and there are also interactions between these quantitative trait loci and the environment. To examine the mechanisms behind the yield reduction of colored rice, the use of near-isogenic lines (NILs) is necessary.

In our previous study, seven pairs of SLs (sister lines generated from a high generation with similar genetic background) were developed for pericarp color (Wang et al. 2009). Two pairs of these SLs with higher near-isogenic levels were selected in the current study to investigate physiological and yield traits, such as flag leaves characteristics, grain characteristics of the top three primary branches of panicles, as well as a series of yield traits. The objective of this study was to elucidate the reasons behind the low-yield production of colored rice.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

SLs for rice pericarp color were constructed by crossing the Zixiangnuo variety of purple pericarp rice with the Chunjiangnuo 2 variety of white pericarp rice.

Consctrution of one pair of SLs: One single ancestral plant obtained in BC1F8 was selected and planted as one line in BC1F9. From the line of BC1F9, two single plants with similar phenotypes but different purple color were selected and planted as two lines. If in BC1F10, there was no segregation in any line on pericarp color and other agronomic traits, the two lines would be considered as a pair of SLs after the evaluation of their level of near-isogenicity by the agronomic trait investigation and SSR marker analysis (Wang et al. 2009).

Two pairs of SLs (P1/W1 and P2/W2, previously recorded as HJF10/HJF11 and HJF40/HJF41, respectively) with high near-isogenic levels were then planted over two years for further research in this current study.

The field experiment were conducted on a farm at China National Rice Research Institute (Fuyang, Zhejiang Province, China) over two seasons (in the years 2009 and 2010 separately). The SLs were planted with three replicates. For each replicate, 40-row plot were planted with 6 plants per row and a space of 16.5 × 23.1 cm between the plants. Identical agronomic practices were conducted in each plot.

The chlorophyll content and the net photosynthetic rate of the flag leaves, the grain filling rate, the grain moisture content and the grain anthocyanin content of the top three primary branches of panicles were investigated during the growth period. Eleven yield traits were determined at the time of maturity. The means of these investigated characteristics and replications were used in data analysis.

Investigation of the physiological traits

Flag Leaf Traits

The chlorophyll content of the flag leaves: From the 5th day until the 35th day after flowering, three flag leaves were randomly selected from the middle of each SL plot and were taken back at nightfall once every 5 days. The sample leaves at a weight of 0.5 g were extracted with a mixed solution of acetone and absolute ethyl alcohol (volume ratio 2 : 1) in the dark at room temperature for 24 h. The optical density (OD) of the extracted solutions was measured at 645- and 663-nm wavelengths using a spectrophotometer. The chlorophyll content of the flag leaves was calculated using the method proposed by Arnon (1949).

The net photosynthetic rate of the flag leaves: Three flag leaves were randomly selected from the middle of each SL plot, and their net photosynthetic rate was measured three times between 9:00 am and 12:00 pm on sunny days using LI-6400 Portable Photosynthesis System produced by American LI-COR Co. Ltd.

Grain traits

Beginning on the 5th day after flowering until the harvest, the panicles from each plot that demonstrated consistent growth were noted, and 9 panicles were randomly taken from each plot to sample for 3 traits (grain filling rate, grain moisture content and grain anthocyanin content) every 5 days. These three different grain traits for the noted panicles were investigated.

Grain filling rate and grain moisture content for the top three primary branches of panicles: For each sample, grains from top three primary branches of panicles were selected and husked. Then the fresh weight of the grains is represented here as G. The grains were dried at 105°C for 1 h and then were kept at 80°C until they reached a constant weight. The dry weight of the grains is represented here as W, and the number of grains is represented as N. Formulas used to determine the grain filling rate and the grain moisture content are as follows:

Grain anthocyanin content of the top three primary-branches of panicles: The grain anthocyanin content for the top three primary-branches of panicles of each SL was measured according to the method proposed by Fuleki (1988). For each sample, the top three primary branches of panicles were selected, from which 10 grains were randomly taken. The grains samples were extracted three times by mixing the grains in a solution of 1.5 mol/L hydrochloric acid (HCl) and 95% ethyl alcohol (volume ratio 15 : 85) in an 80°C water bath for 1 h. The extracted solutions were diluted to a volume of 50 ml and were measured at a 535-nm wavelength using a spectrophotometer.

Investigation of yield traits

Three individual plants were randomly selected from the middle of each SL plot after the plants had reached maturity. We measured eleven yield traits, such as panicle number per plant, spikelet number per panicle, seed setting rate, 1000-grain weight, yield per plot, grain length, grain width, grain thickness, brown rice length, brown rice width and brown rice thickness. Yield per plot was obtained by averaging the yield of three replications. For each replication, 240 indviduals were planted in 7.5 m2 areas.

Results

Physiological traits analysis for the two pairs of SLs

Flag leaf traits

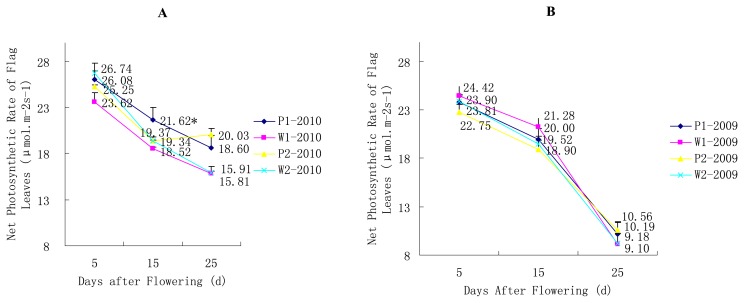

In general, similar trends were found in each year for the net photosynthetic rates of the flag leaves between the P lines and W lines (Fig. 1A, 1B). The net photosynthetic rate decreased with time, and there was only a small difference in the trends between the year 2009 and 2010. In the year 2010, the net photosynthetic rate of the P line was significant or extremely significant greater than that of the W line at the 15th day or the 25th day.

Fig. 1.

Changes in the net photosynthetic rate of the flag leaves for the SLs. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01. (A) Changes in the net photosynthetic rate of the flag leaves for the pairs of P1/W1 and P2/W2 SLs in the year 2010. (B) Changes in the net photosynthetic rate of the flag leaves for the pairs of P1/W1 and P2/W2 SLs in the year 2009.

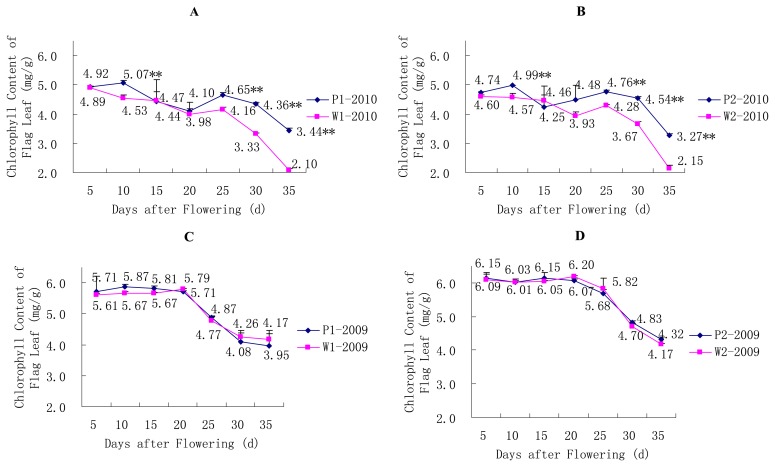

In terms of the variation in the chlorophyll content of the flag leaves, similar trends were demonstrated for the year 2009 and equivalent levels of chlorophyll content were found in the P and W lines (Fig. 2C, 2D). However, the chlorophyll content of the P1 and P2 lines was greater at most time points (extremely significant at the 10th, 25th, 30th and 35th day after flowering) than that of the W lines in the year 2010, although general similar trends were observed over the total growth period between the P and W lines. For P lines in the year 2010, bimodal curves could be obviously observed (Fig. 2A, 2B).

Fig. 2.

Changes in chlorophyll content of the flag leaves for the SLs. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01. (A) Changes in chlorophyll content of the flag leaves for the pair of P1/W1 SLs in the year 2010. (B) Changes in chlorophyll content of the flag leaves for the pair of P2/W2 SLs in the year 2010. (C) Changes in chlorophyll content of the flag leaves for the pair of P1/W1 SLs in the year 2009. (D) Changes in chlorophyll content of the flag leaves for the pair of P2/W2 SLs in the year 2009.

Grain traits

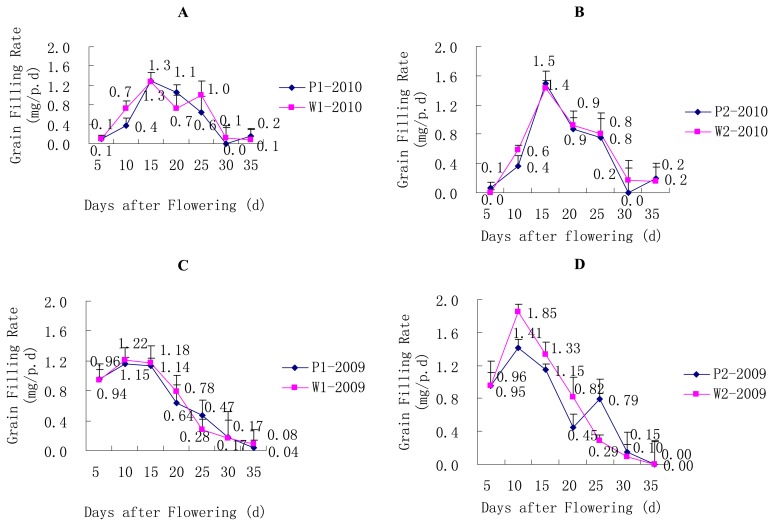

It was showed that grain filling rate of the SLs reached its maximum at the 10th day after flowering in the year 2009 (Fig. 3C, 3D), and at the 15th day in the year 2010 (Fig. 3A, 3B). In general, similar trends and equivalent grain-filling rates were found in both years between the P lines and the corresponding W lines, although the P lines experienced a small rebound at the 35th day after flowering in the year 2010.

Fig. 3.

Changes in grain filling rate for the SLs. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01. (A) Changes in grain filling rate for the pair of P1/W1 SLs in the year 2010. (B) Changes in grain filling rate for the pair of P2/W2 SLs in the year 2010. (C) Changes in grain filling rate for the pair of P1/W1 SLs in the year 2009. (D) Changes in grain filling rate for the pair of P2/W2 SLs in the year 2009.

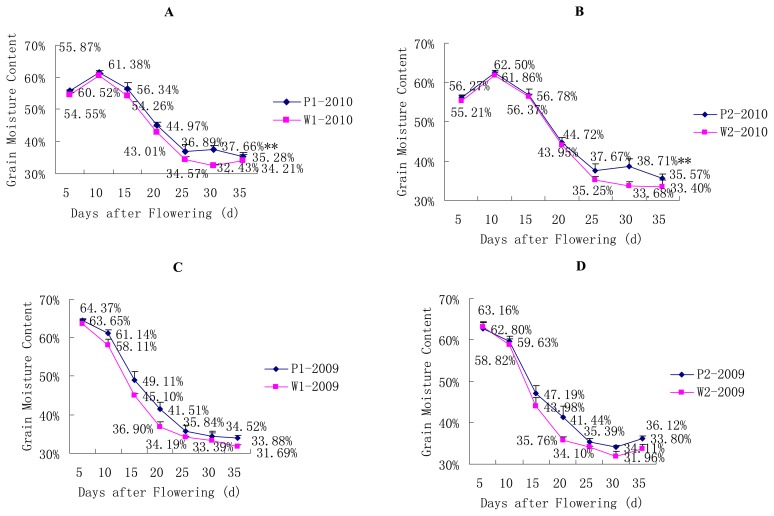

The trends regarding grain moisture content were generally similar between the P and corresponding W lines in both years, although the P lines experienced a small rebound at the 30th day after flowering in the year 2010 (Fig. 4A, 4B). The grain moisture content reached its maximum at the 5th day after flowering in the year 2009 (Fig. 4C, 4D) and at the 10th day after flowering in the year 2010. As showed in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4, the previous period with the maximum grain filling rate corresponded to the period with greatest grain moisture content, and the previous time point of the rebound point for the grain filling rate corresponded to the rebound point for the grain moisture content.

Fig. 4.

Changes in grain moisture content for the SLs. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01. (A) Changes in grain moisture content for the pair of P1/W1 SLs in the year 2010. (B) Changes in grain moisture content for the pair of P2/W2 SLs in the year 2010. (C) Changes in grain moisture content for the pair of P1/W1 SLs in the year 2009. (D) Changes in grain moisture content for the pair of P2/W2 SLs in the year 2009.

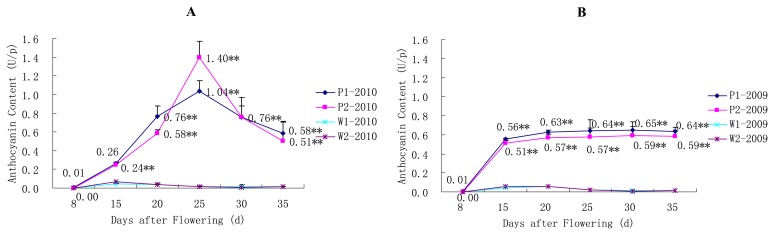

There were large differences between the grain anthocyanin content of the W and P lines in both years (Fig. 5A, 5B); namely, the grain anthocyanin content of the P lines was much greater than that of the W lines and grain anthocyanin content of the W lines was low throughout the entire growth period. The trends regarding grain anthocyanin content of the P lines were different between the two years. In the year 2009, the grain anthocyanin content increased dramatically between the 8th day and 15th day after flowering, and remained steady after that period (Fig. 5B). However in the year 2010, there was a gradual increase in the anthocyanin content between the 8th and 25th day after flowering (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, the maximal anthocyanin contents of the P line in the year 2010 were reached at the 25th day, and then decreased to the similar level observed in the year 2009.

Fig. 5.

Changes in grain anthocyanin content for the SLs. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01. (A) Changes in grain anthocyanin content for the pairs of P1/W1 and P2/W2 SLs in the year 2010. (B) Changes in grain anthocyanin content for the pairs of P1/W1 and P2/W2 SLs in the year 2009.

In conclusion, the physiological function of the P lines were more active than that of corresponding W lines in the year 2010 as demonstrated by the greater chlorophyll content and the net photosynthetic rate of the flag leaves of the P lines. And grain anthocyanin content of P lines demonstrated much higher level during their growth period of the year 2010 than the year 2009. These results suggest that the chlorophyll content of flag leaves, the net photosynthetic rate of the flag leaves and the grain anthocyanin content are more easily influenced by the environment than the grain filling rate or the grain moisture content.

Yield traits analysis for the two pairs of SLs

The t-test results of the differences between the yield traits of the SLs with different pericarp colors are showed in Table 1. No significant differences were found for panicle number per plant, spikelet number per panicle, grain length, grain width, brown rice length, brown rice width, or seed setting rate between the P and W lines in either year. However, there were significant differences in the 1000-grain weight, yield per plot, grain thickness and brown rice thickness. The W lines had larger 1000-grain weights, higher yield per plot and significantly thicker of grain or brown rice than the corresponding P lines, which suggested that the W lines had a larger sink size than the corresponding P lines and that the low 1000-grain weight and yield of the P lines may have been due to their limited sink size.

Table 1.

Comparison on yield traits for the SLs

| Year | SL line | Pericarp color | Panicle number per plant | Spikelet number per panicle | Seed set ting rate (%) | 1000-grain weight (g) | Yield per plot (kg) | Grain (mm) | Brown rice (mm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Grain length | Grain width | Grain thickness | Brown rice length | Brown rice width | Brown rice thickness | ||||||||

| 2010 | P1 | Purple | 10.2 | 109.1 | 85.14 | 23.96 | 5.71 | 8.00 | 3.60 | 2.08 | 5.18 | 2.94 | 1.84 |

| W1 | White | 10.7 | 104.4 | 81.05 | 25.46* | 6.13* | 7.77 | 3.59 | 2.21** | 5.13 | 2.83 | 1.96** | |

| P2 | Purple | 9.4 | 136.9 | 79.55 | 23.14 | 4.94 | 8.39 | 3.61 | 2.00 | 5.36 | 2.80 | 1.76 | |

| W2 | White | 8.8 | 136.2 | 77.00 | 25.66** | 5.78** | 8.24 | 3.52 | 2.15** | 5.36 | 2.80 | 1.93** | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| 2009 | P1 | Purple | 13.0 | 175.8 | 83.03 | 21.15 | 6.10 | 7.73 | 3.31 | 1.90 | 5.15 | 2.74 | 1.77 |

| W1 | White | 12.9 | 167.0 | 84.15 | 24.07** | 6.78** | 7.70 | 3.33 | 2.07** | 5.22 | 2.75 | 1.93* | |

| P2 | Purple | 13.8 | 161.0 | 81.21 | 19.89 | 5.54 | 7.91 | 3.26 | 1.91 | 5.36 | 2.74 | 1.78 | |

| W2 | White | 13.0 | 152.9 | 81.02 | 26.24** | 6.56** | 7.89 | 3.27 | 2.17** | 5.42 | 2.81 | 2.00** | |

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01.

Discussion

Although extensive research into the yield variation of colored rice has been reported in recent years (Cai 2001a, 2001b, 2002, He et al. 1997, Wang and Guo 1994, Xie et al. 2001, Zhang et al. 1994), the reasons behind this yield reduction are not known clearly. In this study, SLs for pericarp color were used, and a series of physiological and yield traits of these SLs were investigated. The results demonstrated smaller 1000-grain weight, lower yield per plot and reduced grain/brown rice thickness in the P lines in both years. In addition, certain physiological traits were found to be different between P and W lines in each year.

In the year 2009, the P lines had greater grain anthocyanin content but lower 1000-grain weights and grain/brown rice that was less thick than the corresponding W lines. Except for the grain/brown rice thickness, the P and W lines had similar sinks according to a comparison of their yield traits. These results suggest that a reduced sink size may have resulted in the decreased 1000-grain weight and yield per plot. Furthermore, the accumulation of grain anthocyanin undoubtedly drained the plant of its photosynthetic products, which may partially explain the decreased yields of the P lines.

Leaf photosynthesis in rice is easily affected by environment factors (Teng et al. 2004). In the year 2010, the P lines had a higher chlorophyll content and a greater net photosynthetic rate in their flag leaves than the corresponding W lines. However, the 1000-grain weight and the grain/brown rice sizes of the P lines were less than those of the W lines. Therefore, although the physiological functions of the P lines appeared more active due to environment factors, the smaller sink size limited the yield potential.

Grain anthocyanin content can be easily influenced by environment factors as its certain gene expression has been correlated with ambient temperature during seedling growth (Bong et al. 2007). The grain anthocyanin contents of the P SLs at the 25th day after flowering in the year 2010 were relatively greater than those in the year 2009, which may have been influenced by the environment and the plant’s active physiological function. At the 35th day after flowering in the year 2010, the grain anthocyanin content of the P lines had declined. This may suggest that the anthocyanin component varied and that the production of other anthocyanins with different peak values could not be detected at the 535-nm wavelength (Sun and Sun 2001).

Though the chlorophyll content and the net photosynthetic rate of the flag leaves, and the grain anthocyanin content of the P lines were easily influenced by the environment, this was not the case for the W lines. Most of the physiological traits were related to source capacities of the rice, although the grain anthocyanin content was related to its sink capacity. We hypothesized that the levels of the chlorophyll content and the net photosynthetic rate increased as source capacities, which led to the increase of the grain anthocyanin content as a sink capacity. Therefore, the transportation from the source to the sink was specific, and there was no increased transportation to grain yield. However, further experimentation is necessary to support this hypothesis.

The grain yield of cereals is determined by the balance between the sink size and the source capacity (Takai et al. 2010). Large sink size is a prerequisite for high yield and high harvest index (Ashraf et al. 1994). In this study, although the source capacity was increased in purple-pericarp rice, its small sink size limited its yield potential. Besides increasing the source capacity, it will be necessary to create a large sink size for breeding purple-pericarp rice.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the High-Tech Research and Development Program in China (No. 2010AA101804), the Special Fund for Center Commonweal Research Institutes (2009RG001-6), the Science and Technology Program of Zhejiang Province (No. 2010C32014) and the Open Fund of State Key Laboratory Breeding Base for Zhejiang Sustainable Pest and Disease Control (2011).

Literature Cited

- Arnon D.I. (1949) Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts: polyphenol-oxidase in Beta Vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 24: 1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf M., Akbar M., Salim M. (1994) Genetic improvement in physiological traits of rice yield. In: Slafer G.A. (ed.) Genetic Improvement of Field Crops, Marcel Dekker Incorporates, New York, pp. 413–455 [Google Scholar]

- Bong G.K., Jeong H.K., Shin Y.M., Kwang-Hee S., Ji H.K., Hong Y.K., Su N.R., Joong-Hoon A. (2007) Anthocyanin content in rice is related to expression levels of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes. Journal of Plant Biology 50: 156–160 [Google Scholar]

- Cai G.Z. (2001a) Effects of different temperature treatments on the coloring of unpolished colorific rice varieties. Journal of Sichuan Agricultural University 19: 366–368 [Google Scholar]

- Cai G.Z. (2001b) Effects of shading on pigmentation of colored milled rice. Journal of Xichang Agricultural College 15: 3–5 [Google Scholar]

- Cai G.Z. (2002) Effects of different fertilizer application on yield properties of colored rice and coloring degree of coarse rice. Southwest China Journal of Agricultura1 Sciences 15: 55–58 [Google Scholar]

- Fuleki (1988) Quantitative methods of anthocyanins. J. of Food Sci. 33: 72–77 [Google Scholar]

- He H.H., Yu Q.Y., He X.P. (1997) A preliminary study on grain-filling characteristics of three special rice varieties. Acta Agriculturae Jiangxi 9: 1–5 [Google Scholar]

- Hyun J.W., Chung H.S. (2004) Cyanidin and malvidin from Oryza sativa cv. Heugjinjubyeo mediate cytotoxicity against human monocytic leukemia cells by arrest of G2/M phase and induction of apoptosis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 52: 2213–2217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamei H., Kojima T., Hasegawa M., Koide T., Umeda T., Yukawa T., Terabe K. (1995) Suppression of tumor cell growth by anthocyanins in vitro. Cancer Invest. 13: 590–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.P., Ouyang L., Li J.N. (1998) The preliminary report on the breeding of three-1ines for black rice. Jiangxi Agricultural Science and Technology 2: 7–9 [Google Scholar]

- Nam S.H., Choi S.P., Kang M.Y., Koh H.J., Kozukue N., Friedman M. (2006) Antioxidative activities of bran from twenty one pigmented rice cultivars. Food Chem. 94: 613–620 [Google Scholar]

- Peng Z.M., Zhang M.W., Tu J.M. (2004) Breeding and nutrient evaluation on three-1ines and their combination of indica black glutinous rice hybrid. Acta Agronomica Sinica 30: 342–347 [Google Scholar]

- Satue-Gracia M., Heinonen I.M., Frankel E.N. (1997) Anthocyanins as antioxidants on human low-density lipoprotein and lecithin-liposome systems. J. Agric. Food Chem. 45: 3362–3367 [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q., Sun B. (2001) Dynamic of seed pigment contents of black kernel wheat at different seed development stages. Scientia Agricultura Sinica 34: 461–464 [Google Scholar]

- Takai T., Kondo M., Yano M., Yamamoto T. (2010) A quantitative trait locus for chlorophyll content and its association with leaf photosynthesis in rice. Rice 3: 172–180 [Google Scholar]

- Teng S., Qian Q., Zeng D.L., Yasufumi K., Kan F., Huang D., Zhu L. (2004) QTL analysis of leaf photosynthetic rate and related physiological traits in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Euphytica 135: 1–7 [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda T., Horio F., Osawa T. (2002) Cyanidin3-O-glucoside suppresses nitric oxide production during a zymosan treatment in rats. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 48: 305–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda T., Horio F., Uchida K., Aoki H., Osawa T. (2003) Dietary cyanidin 3-O-β-d-glucoside-rich purple corn color prevents obesity and ameliorates hyperglycemia in mice. J. Nutr. 133: 2125–2130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Ji Z., Cai J., Ma L., Li X., Yang C. (2009) Construction of near isogenic lines for pericarp color and evaluation on their near isogenicity in rice. Rice Science 16: 261–266 [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.R., Guo Z.J. (1994) The effects of N, P, K supplied at the middle and late growth stages on translocation and distribution of 14C-assimilates and grain yield. Acta Agriculturae Universitatis Jiangxiensis 16: 8–14 [Google Scholar]

- Xie R., Yang Z.L., Zuo Y.S. (2001) Difference comparison of agronomic traits between black and purple pericarp rice and hybrid rice. Southwest China Journal of Agricultural Sciences 14: 83–85 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.W., Zhou J., Peng Z.M. (1994) Effects of different sowing date on yield traits and pigment contents in purple pericarp rice. Journal of Hubei Agricultural Sciences 1: l–4 [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C., Giusti M.M., Malik M., Moyer M.P., Magnuson B.A. (2004) Effects of commercial anthocyanin-rich extracts on colonic cancer and nontumorigenic colonic cell growth. J. Agric. Food Chem. 52: 6122–6128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H., Pan D., Fan Z. (2004) Research and application of Guangdong special rice and investigation on breeding problems. Journal of Guangdong Agricultural Sciences 6: 19–21 [Google Scholar]