Abstract

Fusarium head blight (FHB) is an important disease of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). The aim of this study was to determine the effects of quantitative trait locus (QTL) regions for resistance to FHB and estimate their effects on reducing FHB damage to wheat in Hokkaido, northern Japan. We examined 233 F1-derived doubled-haploid (DH) lines from a cross between ‘Kukeiharu 14’ and ‘Sumai 3’ to determine their reaction to FHB during two seasons under field conditions. The DH lines were genotyped at five known FHB-resistance QTL regions (on chromosomes 3BS, 5AS, 6BS, 2DL and 4BS) by using SSR markers. ‘Sumai 3’ alleles at the QTLs at 3BS and 5AS effectively reduced FHB damage in the environment of Hokkaido, indicating that these QTLs will be useful for breeding spring wheat cultivars suitable for Hokkaido. Some of the QTL regions influenced agronomic traits: ‘Sumai 3’ alleles at the 4BS and 5AS QTLs significantly increased stem length and spike length, that at the 2DL QTL significantly decreased grain weight, and that at the 6BS QTL significantly delayed heading, indicating pleiotropic or linkage effects between these agronomic traits and FHB resistance.

Keywords: agronomic traits, Fusarium head blight, QTL, wheat

Introduction

Fusarium head blight (FHB) is a widespread and destructive disease of small-grain cereals. Apart from losses in grain yield and quality, the most serious threat of FHB is the contamination of the harvested grain with mycotoxins. Especially in Hokkaido, the northern island of Japan, FHB can dramatically reduce the quality and quantity of spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), because the climate during the period from flowering to maturity is usually warm and humid, favoring FHB epidemics. Development of FHB-resistant cultivars is the most cost-effective method to control the disease. However breeding for FHB resistance has been difficult and costly because the inheritance of resistance to FHB is polygenic (Bai and Shaner 1994), and the expression of FHB symptoms varies depending on the environmental conditions. Therefore, DNA marker-assisted selection could complement classical breeding methods, because molecular markers should allow breeders to predict the presence or absence of a specific resistance gene in a breeding line independent of environmental conditions.

Different types of FHB resistance have been described. Three types are generally accepted: resistance to initial infection (Type I), resistance to spread within the spike (Type II), and resistance to accumulation of the mycotoxin deoxynivalenol (DON) (Type III) (Mesterhazy 1995). A number of quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping studies have analyzed the genetic control of FHB resistance, as recently reviewed by Buerstmayr et al. (2009), and the resistance has been re-analyzed using QTL analysis (Loeffler et al. 2009). A major QTL for FHB resistance, Fhb1 (syn. Qfhs.ndsu-3BS), was mapped to the distal end of chromosome 3B in mapping populations derived from ‘Sumai 3’ and its derivatives (Liu et al. 2006). The ‘Sumai 3’ allele at this QTL was associated with Type II resistance (Anderson et al. 2001, Buerstmayr et al. 2002, 2003, Yang et al. 2003). Additional resistance QTLs in ‘Sumai 3’ and its derivatives have been mapped to chromosomes 5AS (Qfhs.ifa-5A; Buerstmayr et al. 2002, 2003) and 6BS (Anderson et al. 2001). Qfhs.ifa-5A may contribute significantly to Type I resistance and slightly to Type II resistance, and the 6BS QTL was associated with Type II resistance (Buerstmayr et al. 2009). QTLs for FHB resistance in the Chinese line ‘Wuhan 1’ (unknown pedigree) were mapped to 2DL and 4BS. Alleles of ‘Wuhan 1’ at these QTLs were associated with Type II resistance (Somers et al. 2003).

The Food Sanitation Council of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare set a provisional limit for DON content in unpolished wheat grains of 1.1 ppm in 2002, and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries stipulated that the percentage of FHB-damaged grains of wheat and barley used for food must be less than 0.05% (Nakajima et al. 2008). It has therefore become important to develop wheat cultivars with low susceptibility to Fusarium infection and low DON content. The objective of this study was to elucidate which QTLs are available for use in breeding to develop improved cultivars suitable for the environment of Hokkaido. We developed 233 F1-derived doubled-haploid (DH) lines from the cross between ‘Kukeiharu 14’ and ‘Sumai 3’. The parents and DH lines were genotyped using SSR markers around these five QTLs and examined in field experiments for the percentage of Fusarium-damaged grains (FDG), the concentration of DON, the FHB severity, and several important agronomic traits. The ultimate goal of this work was to develop an efficient strategy for breeding to improve FHB resistance by examining the positive and negative effects of the QTLs on FHB resistance and agronomic traits.

Material and Methods

Plant materials

We used a population of recombinant F1-derived DH lines in this study. ‘Kukeiharu 14 (KH14)’ was developed at the Hokkaido Central Agricultural Experiment Station by a single cross between ‘Kitamiharu 56’ and ‘Roblin’. It matures early and its grains make high-quality bread, but it is susceptible to FHB. ‘Sumai 3’ is a Chinese FHB-resistant cultivar. ‘KH14’ and ‘Sumai 3’ were crossed in 2000. In 2001, 233 DH lines were developed from field-grown F1 plants by anther culture, as described by Shimada (1995).

Evaluation of FHB resistance and other agronomic traits

The DH population and the parental lines were grown in 2003 and 2004 in a field at the Hokkaido Central Agricultural Experiment Station, at Naganuma. FHB was evaluated in field experiments by natural infection only, since the wet conditions from flowering to maturity ensured that suitable levels of infection would occur. DH lines and parents were duplicated in a randomized complete block design. Each plot consisted of a single 1-m row at a 60-cm row spacing. Sowing density was 100 seeds per row. In 2003, 10 culms were randomly selected, and stem length and spike length were measured. The plants were harvested manually and the seed was threshed in a small threshing machine (Shirakawa Nouki, Japan) at low wind speed. The thousand-grain weight (TGW), percentage of Fusarium-damaged grains (FDG) and DON content (ppb) were measured. DON content was measured with a commercial ELISA kit (FA mycotoxin: DON + nivalenol; Kyowa Medex, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A second set of plots identical to the first set was added to obtain visual disease severity data. The nursery was irrigated by sprinkler for 5 min every hour from heading date to maturity. At 21 days after flowering, we collected 100 spikes per plot and counted the number of infected spikes and rated the infected spikelets on each symptomatic head on a scale of 0 (resistant, with 0% infection) to 10 (highly susceptible, with 100% infection) in 0.5-point increments as an infection index. Overall FHB severity was calculated as (index of infected spikes per plot) × (maximum index of infected spikelets per head).

DNA marker analysis

DNA was extracted from wheat leaves by using the CTAB method of Murray and Thompson (1980), with modifications. About 1 cm of leaf was put into a safe-lock tube (2.0 mL) containing 800 μL of modified 2% CTAB buffer (2% CTAB, 0.1 M Tris·HCl at pH 8.0, 20 mM EDTA at pH 8.0, 1.4 M NaCl) and a stainless steel bead (3 mm). The tube was shaken for 1 min on a Shake Master (Bio Medical Science, Inc., Japan) and then heated in an incubator at 60°C for 30 min. After cooling, 600 μL of chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (24:1 v/v) was added. The tube was shaken and then centrifuged for 15 min at 15 000 × g. Then 600 μL of the upper layer was moved into a new tube (1.5 mL) containing 400 μL of 2-propanol and the tube was shaken and then centrifuged for 15 min at 15 000 × g. The supernatant was discarded and the precipitated DNA pellet was dried for 30 min at room temperature and suspended in 400 μL of Tris-EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA at pH 8.0).

We used microsatellite markers previously mapped around the FHB resistance QTLs identified on chromosomes 3BS, 5AS and 6BS in ‘Sumai 3’ and on chromosomes 2DL and 4B in ‘Wuhan 1’ (Bai et al. 1999, Gupta et al. 2002, McCartney et al. 2004, Röder et al. 1998, Somers et al. 2004). PCR was performed in 10 μL of solution comprising 1 μL of the DNA template (about 50 ng), 2.5 U Taq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems, USA), 1× PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM of each dNTP, 0.02 μM forward primer, 0.18 μM 6-FAM/VIC/NED/PET-labeled M13 primer (5′-ACGACGTTGTAAAACGAC-3′, Applied Bio-systems) and 0.2 μM reverse primer. All forward microsatellite primers were modified to contain a 19-nucleotide 5′ M13 tail (5′-CACGACGTTGTAAAACGAC-3′; Schuelke 2000). PCR amplification used an initial 94°C for 7 min; 35 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 48°C (Xgwm508, Xwmc105, Xwmc710) or 56°C (Xwmc601, Xgwm608, Xgwm539, Xwmc175, Xgwm389, Xgwm533, Xgwm493, Xwmc048, Xwmc238, Xgwm513, Xgwm293, Xwmc705, Xgwm304, Xwmc398, Xmc397) for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min and a final 72°C extension for 5 min. PCR products were separated and detected in an ABI Prism 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) using the GeneScan software and GeneScan-500 LIZ as the size standard.

The genotype at the Rht-B1 locus was determined by the method of Ellis et al. (2002), with modifications. PCR was performed in 10 μL of solution comprising 1 μL of template DNA, 0.5 U HotStar Taq polymerase (Qiagen, Germany), 1× HotStar Taq buffer, 200 μM each dNTP, and 0.4 μM each forward and reverse primer. PCR amplification used an initial 95°C for 15 min, 35 cycles at 95°C for 30 s and 68°C for 2 min and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were separated in 2% agarose gels and stained with SYBR Gold Nucleic Acid Gel stain (Invitrogen, USA).

QTL analysis

The order of the SSR markers around the QTLs was determined by using the MAPMAKER/EXP ver. 3.0b software (Lander et al. 1987, Lincoln et al. 1993). Simple interval mapping (SIM) was done with the Map Manager QTXb20 software (Manly and Olson 1999, Manly et al. 2001). The SIM threshold was based on the results of 1000 permutation tests at the 5% level of significance.

Results

The mean values of FDG and DON of the DH lines in 2003 were 3.5× those in 2004, indicating a more severe FHB outbreak in 2003 (Table 1). The 24-h average temperature from heading to maturity (late June to late July) was 16°C in 2003 and 19°C in 2004. The estimated duration of sunshine was 171.9 h in 2003 and 191.1 h in 2004. The mean values of FDG and DON in the DH lines were higher than those of both parents. The mean value of Fusarium severity in the DH lines was in between those of the parents. Heading date differed by no more than 1 day between 2003 and 2004.

Table 1.

Means and ranges of FHB traits and morphological traits of Sumai 3, Kukeiharu 14 and their DH lines

| Trait | Sumai 3 | Kukeiharu 14 | DH lines | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Mean | Mean | Mean | Range | |

| FDG 2003 (%) | 0.51 | 1.66 | 2.48 | 0.12–10.40 |

| FDG 2004 (%) | 0.09 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.0–4.4 |

| DON 2003 (ppb) | 1146 | 2113 | 2388 | 334–15030 |

| DON 2004 (ppb) | 228 | 590 | 686 | 100–5606 |

| FHB severitya 2004 (index) | 0.25 | 25 | 11.8 | 0.25–68.0 |

| Heading date 2003 (month.day) | 6.26 | 6.20 | 6.21 | 6.16–6.30 |

| Heading date 2004 (month.day) | 6.26 | 6.21 | 6.22 | 6.17–6.28 |

| Stem length 2003 (cm) | 101.3 | 65.3 | 76.1 | 44.3–110.9 |

| Spike length 2003 (cm) | 9.5 | 7.0 | 8.6 | 6.2–11.8 |

| TGW 2003 (g) | 38.2 | 38.3 | 37.8 | 26.7–50.3 |

| TGW 2004 (g) | 34.1 | 35.3 | 34.3 | 24.5–43.8 |

FHB severity was tested in another field where plants were irrigated by sprinkler.

There were positive correlations (P = 0.01) between DON and both FDG and heading date in both years (Table 2). There was a positive correlation between FDG and heading date in 2003 but not in 2004. FHB severity was correlated with FDG and with all agronomic traits that we investigated. A negative correlation was found between FDG and spike length.

Table 2.

Correlations of FHB traits and agronomic traits in the DH lines derived from the cross between KH14 and Sumai 3

| Trait | FDG 2003 | FDG 2004 | DON 2003 | DON 2004 | FHB severity 2004 | Heading date 2003 | Heading date 2004 | Stem length 2003 | Spike length 2003 | TGW 2003 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDG 2004 | 0.534** | |||||||||

| DON 2003 | 0.728** | 0.484** | ||||||||

| DON 2004 | 0.519** | 0.649** | 0.673** | |||||||

| FHB severity 2004 | 0.155* | 0.284** | −0.057 | 0.069 | ||||||

| Heading date 2003 | 0.174** | 0.022 | 0.438** | 0.277** | −0.471** | |||||

| Heading date 2004 | 0.104 | −0.036 | 0.346** | 0.233** | −0.498** | 0.853** | ||||

| Stem length 2003 | −0.056 | −0.109 | 0.097 | −0.012 | −0.308** | 0.194** | 0.251** | |||

| Spike length 2003 | −0.150* | −0.275** | −0.02 | −0.106 | −0.305** | 0.111 | 0.131** | 0.551** | ||

| TGW 2003 | −0.001 | 0.007 | −0.021 | −0.101 | 0.222** | −0.262** | −0.140* | 0.334** | 0.222** | |

| TGW 2004 | 0.111 | 0.116 | 0.09 | 0.025 | 0.277** | −0.262** | −0.256** | 0.272** | 0.219** | 0.839** |

Significantly different from 0 at P = 0.05;

significantly different from 0 at P = 0.01.

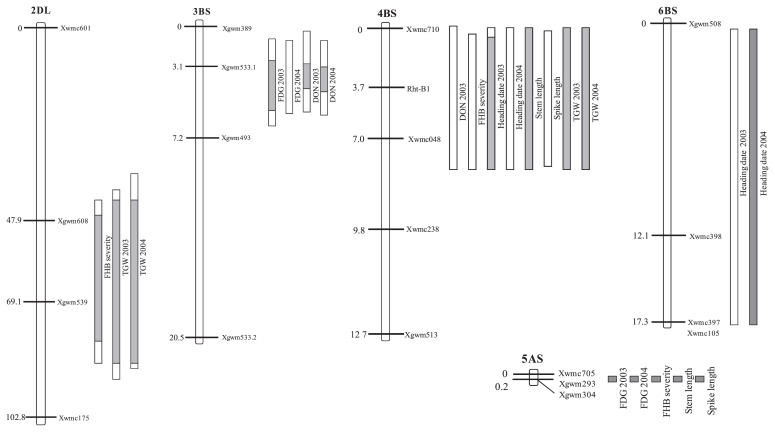

QTLs for FDG were detected on chromosomes 3BS and 5AS, for DON content at 3BS and for FHB severity at 2DL, 5AS and 4BS (Table 3 and Fig. 1). QTLs for agronomic traits were detected near the same regions except for 3BS: highly significant QTLs for heading date were detected at 4BS and 6BS, for stem length and spike length at 4BS and 5AS and for TGW at 2DL and 4BS (Table 3 and Fig. 1). Supplemental Table 1 summarizes the effects of the alleles on the measured traits. The ‘Sumai 3’ allele at the 2DL QTL decreased FHB severity by 0.8 to 7.5 percentage points, and decreased TGW by about 0 to 3.4 g. The ‘Sumai 3’ allele at the 3BS QTL decreased FDG by 0.21 to 0.55 percentage points and DON by more than 500 ppb for three of four markers. The 4BS region from ‘Sumai 3’ was associated with increased DON content (by around 400 ppb), a stem length increase of about 12 to 14 cm, a spike length increase of about 0.2 to 0.4 cm, and a TGW increase of about 1.9 to 2.5 g, and delayed heading by 1 day. The ‘Sumai 3’ allele at the 5AS QTL decreased FDG by about 0.6 percentage points, DON by about 260 ppb, and FHB severity by 3.4 to 5.5 units, and increased stem length by about 6 cm and spike length by about 0.4 cm. The ‘Sumai 3’ allele at the 6BS QTL delayed heading by 1 to 2 days (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 3.

FHB resistance and morphological QTLs detected by simple interval mapping in a DH population from the cross between KH14 and Sumai 3

| Trait | Chr. | 2003 | 2004 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Flanking markers | LODa | PVEb | AEc | Flanking markers | LODa | PVEb | AEc | ||

| FDG (%)d | 3BS | Xgwm533.1-Xgwm493 | 3.6 | 0.07 | −0.45 | Xgwm533.1-Xgwm493 | 2.1 | 0.04 | −0.16 |

| 5AS | Xwmc705-Xgwm304 | 4.3 | 0.08 | −0.46 | Xwmc705-Xgwm304 | 4.8 | 0.09 | −0.19 | |

|

| |||||||||

| DON (ppb) | 3BS | Xgwm389-Xgwm533.1 | 2.9 | 0.05 | −519 | Xgwm389-Xgwm533.1 | 2.9 | 0.06 | −147 |

| 4BS | Xwmc710-Xgwm513 | 2.5 | 0.05 | 403 | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| FHB severity (index) | 2DL | Xgwm608-Xwmc175 | 4.8 | 0.09 | −7.93 | ||||

| 4BS | Xwmc710-Xgwm513 | 1.4 | 0.03 | −2.15 | |||||

| 5AS | Xwmc705-Xgwm304 | 2.6 | 0.05 | −2.83 | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Heading date (day) | 4BS | Xwmc710-Xgwm513 | 3.5 | 0.08 | 1 | Xwmc710-Xgwm513 | 1.8 | 0.04 | 1 |

| 6BS | Xgwm508-Xgwm397 | 1.8 | 0.04 | 1 | Xgwm508-Xgwm397 | 3.8 | 0.07 | 1 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Stem length (cm) | 4BS | Xwmc710-Xgwm513 | 18.9 | 0.32 | 7.95 | ||||

| 5AS | Xwmc705-Xgwm304 | 3.3 | 0.06 | 3.49 | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Spike length (cm) | 4BS | Xwmc710-Xgwm513 | 1.6 | 0.03 | 0.24 | ||||

| 5AS | Xwmc705-Xgwm304 | 5.6 | 0.11 | 0.44 | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| TGWe (g) | 2DL | Xgwm608-Xwmc175 | 10.9 | 0.20 | −4.24 | Xgwm608-Xwmc175 | 8.3 | 0.15 | −3.05 |

| 4BS | Xwmc710-Xgwm513 | 5.2 | 0.10 | 1.55 | Xwmc710-Xgwm513 | 3.5 | 0.07 | 1.00 | |

The threshold logarithm of odds value was based on the results of 1000 permutation tests at the 5% level of significance.

Proportion of phenotypic variance explained by the detected QTLs.

Additive effect of Sumai 3 allele.

FDG: Fusarium-damaged grains.

TGW: thousand grain weight.

Fig. 1.

Linkage map of QTLs for FHB resistance—FDG (Fusarium-damaged grains), DON (concentration of deoxynivalenol) and FHB severity —and QTLs for agronomic traits—heading date, stem length, spike length and TGW (thousand-grain weight). The white boxes correspond to the regions in which LOD > threshold by 1000 permutation tests in simple interval mapping. The gray bars correspond to the regions in which LOD > 2.5.

Lines with the ‘Sumai 3’ genotype at both 3BS and 5AS had significantly (P < 0.05) lower FDG, DON, and FHB severity and significantly greater stem length, spike length, and TGW than lines with the ‘KH14’ genotype at both loci (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of alternative alleles at two QTL regions (3BS and 5AS) on FHB and agronomic traits

| Allele typea | No. of lines | FDGb,c (%) | DONb (ppb) | FHB severity | Stem length (cm) | Spike length (cm) | TGW (g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| 3BS | 5AS | |||||||

| Sumai 3 | Sumai 3 | 52 | 1.09 a | 1162 a | 7.0 a | 80.9 a | 9.2 a | 36.9 a |

| Sumai 3 | KH14 | 44 | 1.47 a | 1280 a | 12.9 b | 74.0 ab | 8.2 b | 35.9 b |

| KH14 | Sumai 3 | 70 | 1.44 a | 1598 ab | 10.8 ab | 77.6 ab | 8.8 a | 36.1 ab |

| KH14 | KH14 | 66 | 2.21 b | 1941 b | 15.8 b | 71.2 b | 8.0 b | 35.5 b |

Genotypes were determined by Xgwm533.1 for the 3BS QTL and by Xgwm293 for the 5AS QTL.

Average of two years’ data (2003 (2004).

Values within a column followed by different letters are significantly different according to the Kruskal-Wallis test (P = 0.05).

Discussion

SIM detected five FHB resistance QTLs in the ‘Kukeiharu 14’ × ‘Sumai 3’ DH population. Our analysis found correlations between FHB resistance QTLs (except 3BS) and some morphological traits that segregated in the mapping population. We do not know whether the correlation indicates pleiotropic effects of the resistance QTLs or tight linkage of QTLs for resistance and plant development.

Highly significant QTLs for FHB severity and TGW were detected around Xgwm539 at 2DL (Fig. 1) and the ‘Sumai 3’ allele decreased FHB severity (Table 3). Somers et al. (2003) reported a QTL for Type I resistance at 2DL (the resistance allele in ‘Wuhan 1’). We believe that the 2DL region from ‘Sumai 3’ has the same effect as that from ‘Wuhan 1’, because our evaluation of FHB severity also investigated type I resistance. However, the ‘Sumai 3’ allele at this QTL decreased TGW (Table 3). If this represents linkage rather than a pleiotropic effect, this linkage needs to be broken by using a fine mapping approach.

The ‘Sumai 3’ allele at the 3BS QTL strongly reduced FDG and DON (Table 3). The 3BS QTL has been widely validated by using ‘Sumai 3’ and its derivatives (Anderson et al. 2001, Buerstmayr et al. 2002, Yang et al. 2005, Zhou et al. 2002). This QTL, named Fhb1, is known to contribute to Type II resistance (Cuthbert et al. 2006, Liu et al. 2006, Waldron et al. 1999), and Fhb1 was fine-mapped as a major gene controlling FHB resistance (Cuthbert et al. 2006, Liu et al. 2006). We believe that the FHB resistance QTL detected in the present study was Fhb1, but this should be confirmed by fine-scale mapping. The QTL was not significantly associated with the other agronomic traits that we tested (Table 3 and Fig. 1). Therefore, it can be used in applied breeding without undesirable effects on morphological characteristics.

The ‘Sumai 3’ allele at the 4BS QTL decreased FHB severity (Table 3). Somers et al. (2003) reported a QTL at 4BS for Type I resistance in ‘Wuhan 1’. Lin et al. (2006) also detected a QTL for Type I resistance at 4BS in ‘Wangshuibai’. Our results suggest that ‘Sumai 3’, ‘Wuhan 1’ and ‘Wangshuibai’ share the same resistance allele at the 4BS QTL. However, the 4BS region from ‘Sumai 3’ was associated with increased DON content, stem length, spike length, and TGW and with delayed heading (Table 3 and Fig. 1). There may be many genes connected with agronomic traits in this region. For example, Somers et al. (2004) mapped Rht-B1 at 4BS. ‘KH14’ carries Rht-B1b (which produces a semi-dwarf type) and ‘Sumai 3’ carries Rht-B1a (which produces the wild-type phenotype). Rht-B1b from ‘Soissons’ increased Type II resistance (Srinivasachary et al. 2009). The ‘Sumai 3’ allele at the 4BS QTL might therefore decrease Type II resistance and consequently this allele might increase the DON content. The usefulness of the 4BS QTL in wheat breeding therefore needs further investigation.

Previous studies detected QTLs for Types I and II resistance at 5AS (Buerstmayr et al. 2002, 2003, Yang et al. 2005). The ‘Sumai 3’ allele at the 5AS QTL decreased FDG, DON and FHB severity and increased stem length and spike length. Taller lines might escape infection because their spikes are further from fungi in the soil and are exposed to lower humidity (Somers et al. 2003). Therefore, it is important to consider possible pleiotropic effects of plant development on FHB infection. DH lines with the ‘Sumai 3’ allele for the 5AS QTL were about 7 cm taller than those with the ‘KH14’ allele (Table 4). If FHB resistance and plant height are controlled by different QTLs, we must develop recombinant lines to break the linkage between resistance QTLs and plant height QTLs. Fhb5, which is the FHB resistance QTL at 5AS in ‘Wangshuibai’, has been fine-mapped (Xue et al. 2011) within a 0.3-cM interval. Fine mapping can facilitate the development of recombinant lines that can be used to break or reduce this kind of linkage.

Fhb2, which confers field resistance to FHB, was mapped at 6BS (Cuthbert et al. 2007). A QTL for heading date was mapped near Fhb2 by using recombinant inbred lines derived from the cross between ‘Ning7840’ (a ‘Sumai 3’ derivative) and ‘Clark’ (Marza et al. 2006). The ‘Sumai 3’ allele at the 6BS QTL delayed heading by 1 day (Supplemental Table 1). We found a positive correlation between FDG and heading date in 2003, so the effect of the 6BS region on FHB resistance might have been partly masked by its effect on heading date. Overall, the effect of the 6BS QTL was relatively small in the ‘Sumai 3’ × ‘KH14’ progeny that we investigated.

FDG and DON were higher in 2003 than in 2004 (Table 1). The duration of sunshine was shorter in 2003, possibly increasing natural infection. The average temperature from heading to maturity was lower in 2003. The optimum temperature for infection is about 28°C for both Fusarium graminearum (DON-producing) and Fusarium avenaceum (not DON-producing), but the minimum temperature required for infection is lower for F. graminearum (Rossi et al. 2001). Although we did not investigate the species of fungus, the DON data suggest that infection by F. graminearum was higher in 2003 than in 2004. The mean FDG and DON values in the DH lines were higher than the values in the susceptible parent (Table 1). ‘KH14’ (an early-heading line) had lower FDG and DON even though it is susceptible, since there were positive correlations between FDG and heading date in 2003 and between DON and heading date in 2003 and 2004 (Table 2). The significant correlation of FHB severity with FDG and with all agronomic traits that we investigated (Table 2) suggests that FHB resistance is closely related to agronomic traits.

There were correlations between the locations of loci for FHB resistance and those for morphological traits (Fig. 1). DH lines with the ‘Sumai 3’ alleles at both the 3BS and 5AS QTLs had significantly increased stem length, spike length, and TGW and significantly less FDG (Table 4). Lines with the ‘Sumai 3’ allele at the 2DL QTL had decreased FHB severity and TGW (Supplemental Table 1). In our breeding strategy, we first discarded lines with tall plants because the semi-dwarf phenotype resists lodging and is preferred under Japanese conditions, and then selected lines with a low score for FHB severity. Because of this strategy, we might have discarded FHB-resistant lines because of their plant height, and might have selected lines with small grains and a low score for FHB severity. Therefore, our strategy has not developed FHB-resistant lines with the same agricultural performance as leading cultivars that are adapted to Hokkaido conditions.

Buerstmayr et al. (2002, 2003) stated that the two QTLs at 3BS and 5AS together explained 40 to 48% of the phenotypic variance, depending on the FHB resistance trait, in a DH population derived from ‘CM-82036’ × ‘Remus’. The lines with ‘Sumai 3’ genotypes at both 3BS and 5AS had significantly reduced FDG, DON and FHB severity (Table 4). We could consequently utilize the QTLs at 3BS and 5AS for developing FHB-resistant wheat cultivars. These QTLs conferred higher efficacy against FHB than the other three QTLs that we investigated, and showed significantly greater effects in combination (Table 4). Salameh et al. (2011) reported no systematic negative effect on grain yield, TGW, hectoliter weight and protein content in European winter wheat lines that contained the 3BS and 5AS QTLs from ‘CM-82036’. These two QTLs therefore appear to be the most promising candidates for use in marker-assisted selection, which fully agrees with the conclusions of Buerstmayr et al. (2003) and Chen et al. (2006). Further detailed analysis of all five QTLs will be required to overcome the problem of their tight linkage to agronomic traits with negative effects for the breeding of wheat cultivars that are strongly resistant to FHB.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. H. Buerstmayr, University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences, IFA-Tulln, Austria, for critically reading an early version of the manuscript, and Drs. A. Torada and N. Iwata, Hokuren Agricultural Research Institute, Naganuma, Hokkaido, for their advice on QTL mapping. This work was supported by grants from Hokunou Chuoukai and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (Genomics for Agricultural Innovation, TRG1006).

Literature Cited

- Anderson J.A., Stack R.W., Liu S., Waldron B.L., Fjeld A.D., Coyne C., Moreno-Sevilla B., Fetch J.M., Song Q.J., Cregan P.B., et al. (2001) DNA markers for Fusarium head blight resistance QTLs in two wheat populations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 102: 1164–1168 [Google Scholar]

- Bai G., Shaner G. (1994) Scab of wheat: prospects for control. Plant Dis. 78: 760–766 [Google Scholar]

- Bai G., Kolb F.L., Shaner G., Domier L. (1999) Amplified fragment length polymorphism markers linked to a major quantitative trait locus controlling scab resistance in wheat. Phytopathology 89: 343–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buerstmayr H., Lemmens M., Hartl L., Doldi L., Steiner B., Stierschneider M., Ruckenbauer P. (2002) Molecular mapping of QTLs for Fusarium head blight resistance in spring wheat. I. Resistance to fungal spread (Type II resistance). Theor. Appl. Genet. 104: 84–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buerstmayr H., Steiner B., Hartl L., Griesser M., Angerer N., Lengauer D., Miedaner T., Schneider B., Lemmens M. (2003) Molecular mapping of QTLs for Fusarium head blight resistance in spring wheat. II. Resistance to fungal penetration and spread. Theor. Appl. Genet. 107: 503–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buerstmayr H., Ban T., Anderson J.A. (2009) QTL mapping and marker-assisted selection for Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat; a review. Plant Breed. 128: 1–26 [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Griffey C.A., Maroof M.A.S., Stromberg E.L., Biyashev R.M., Zhao W., Chappell M.R., Pridgen T.H., Dong Y., Zeng Z. (2006) Validation of two major quantitative trait loci for Fusarium head blight resistance in Chinese wheat line W14. Plant Breed. 125: 99–101 [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert P.A., Somers D.J., Thomas J., Cloutier S., Brulé-Babel A. (2006) Fine mapping Fhb1, a major controlling Fusarium head blight resistance in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 112: 1465–1472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert P.A., Somers D.J., Brulé-Babel A. (2007) Mapping of Fhb2 on chromosome 6BS: a gene controlling Fusarium head blight field resistance in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 114: 429–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis M.H., Spielmeyer W., Gale K.R., Rebetzke G.J., Richards R.A. (2002) “Perfect” markers for the Rht-D1b dwarfing genes in wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 105: 1038–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta P.K., Balyan H.S., Edwards K.J., Issac P., Korzun V., Röder M.S., Gautier M.F., Joudrier P., Schlatter A.R., Dubcovsky J., et al. (2002) Genetic mapping of 66 new microsatellite (SSR) loci in bread wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 105: 413–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander E.S., Green P., Abrahamson J., Barlow A., Daly M.J., Lincoln S.E., Newburg L. (1987) MAPMAKER: an interactive computer package for constructing primary genetic linkage maps of experimental and natural populations. Genomics 1: 174–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin F., Xue S.L., Zhang Z.Z., Zhang C.Q., Kong Z.X., Yao G.Q., Tian D.G., Zhu H.L., Li C.J., Cao Y., et al. (2006) Mapping QTL associated with resistance to Fusarium head blight in the Nanda 2419 × Wangshuibai population. II: Type I resistance. Theor. Appl. Genet. 112: 528–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln S.E., Daly M.J., Lander E.S. (1993) Constructing genetic maps with MAPMAKER/EXP version 3.0: a tutorial and reference manual. Technical Report, 3rd edn Whitehead Institute for the Biomedical Research, Cambridge [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Zhang X., Pumphrey M.O., Stack R.W., Gill B.S., Anderson J.A. (2006) Complex microcolinearity among wheat, rice, and barley revealed by fine mapping of the genomic region harboring a major QTL for resistance to Fusarium head blight in wheat. Funct. Integr. Genomics 6: 83–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeffler M., Schoen C.C., Miedaner T. (2009) Revealing the genetic architecture of FHB resistance in hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) by QTL meta-analysis. Mol. Breed. 23: 473–488 [Google Scholar]

- Manly K.F., Olson J.M. (1999) Overview of QTL mapping software and introduction to map manager QT. Mamm. Genome 4: 327–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly K.F., Cudmore R.H., Meer J.M. (2001) Map Manager QTX, cross-platform software for genetic mapping. Mamm. Genome 12: 930–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marza F., Bai G.H., Carver B.F., Zhou W.C. (2006) Quantitative trait loci for yield and related traits in the wheat population Ning7840 × Clark. Theor. Appl. Genet. 112: 688–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartney C.A., Somers D.J., Fedak G., Cao W. (2004) Haplotype diversity at Fusarium head blight resistance QTLs in wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 109: 261–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesterhazy A. (1995) Types and components of resistance to Fusarium head blight. Plant Breed. 114: 377–386 [Google Scholar]

- Murray M.G., Thompson W.F. (1980) Rapid isolation of high molecular weight DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 8: 4321–4326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima T., Yoshida M., Tomimura K. (2008) Effect of lodging on the level of mycotoxins in wheat, barley, and rice infected with the Fusarium graminearum species complex. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 74: 289–295 [Google Scholar]

- Röder M.S., Korzun V., Wendehake K., Plaschke J., Tixier H., Leroy P., Ganal W. (1998) A microsatellite map of wheat. Genetics 149: 2007–2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi V., Ravanetti A., Pattori E., Giosue S. (2001) Influence of temperature and humidity on the infection of wheat spikes by some fungi causing Fusarium head blight. J. Plant Pathol. 83: 189–198 [Google Scholar]

- Salameh A., Buerstmayr M., Steiner B., Neumayer A., Lemmens M., Buerstmayr H. (2011) Effect of introgression of two QTL for fusarium head blight resistance from Asian spring wheat by marker-assisted backcrossing into European winter wheat on fusarium head blight resistance, yield and quality traits. Mol. Breed. 28: 485–494 [Google Scholar]

- Schuelke M. (2000) An economic method for fluorescent labeling of PCR fragments. Nat. Biotechnol. 18: 233–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada T. (1995) Anther culture of Japanese spring wheat Haruhikari and characterization of doubled haploid plants. Bull. Res. Inst. Agric. Resour., Ishikawa Agric. Coll. 4: 17–22 [Google Scholar]

- Somers D.J., Fedak G., Savard M. (2003) Molecular mapping of novel genes controlling Fusarium head blight resistance and deoxynivalenol accumulation in spring wheat. Genome 46: 555–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers D.J., Issac P., Edwards K. (2004) A high-density micro-satellite consensus map for bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 109: 1105–1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasachary, Gosman N., Steed A., Hollins T.W., Bayles R., Jennings P., Nicholson P. (2009) Semi-dwarfing Rht-B1 and Rht-D1 loci of wheat differ significantly in their influence on resistance to Fusarium head blight. Theor. Appl. Genet. 118: 695–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron B.L., Moreno-Sevilla B., Anderson J.A., Stack R.W., Frohberg R.C. (1999) RFLP mapping of QTL for Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Crop Sci. 39: 805–811 [Google Scholar]

- Xue S., Xu F., Tang M., Zhou Y., Li G., An X., Lin F., Xu H., Jia H., Zhang L., et al. (2011) Precise mapping Fhb5, a major QTL conditioning resistance to Fusarium infection in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Theor. Appl. Genet. 123: 1055–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Gilbert J., Fedak G., Procunier J.D., Somers D.J., McKenzie I.H. (2003) Marker-assisted selection of Fusarium head blight resistance genes in two doubled-haploid populations of Wheat. Mol. Breed. 12: 309–317 [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Gilbert J., Fedak G., Somers D.J. (2005) Genetic characterization of QTL associated with resistance Fusarium head blight in a doubled-haploid spring wheat population. Genome 48: 187–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W.C., Kolb F.L., Bai G.H., Shaner G., Domier L.L. (2002) Genetic analysis of scab resistance QTLs in wheat with micro-satellite and AFLP markers. Genome 45: 719–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.