Abstract

Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), unlike other muscle cells, do not terminally differentiate. In response to injury, VSMCs change phenotype, proliferate, and migrate as part of the repair process. Dysregulation of this plasticity program contributes to the pathogenesis of several vascular disorders, such as atherosclerosis, restenosis, and hypertension. The discovery of mutations in the gene encoding BMPRII, the type II subunit of the receptor for bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) provided an indication that BMP signaling may affect the homeostasis of VSMCs and their phenotype modulation. Here we report that BMP signaling potently induces SMC-specific genes in pluripotent cells and prevents dedifferentiation of arterial SMCs. The BMP-induced phenotype switch requires intact RhoA/ROCK signaling but is not blocked by inhibitors of the TGFβ and PI3K/Akt pathways. Furthermore, nuclear localization and recruitment of the myocardin-related transcription factors (MRTF-A and MRTF-B) to a smooth muscle α-actin promoter is observed in response to BMP treatment. Thus, BMP signaling modulates VSMC phenotype via cross-talk with the RhoA/MRTFs pathway, and may contribute to the development of the pathological characteristics observed in patients with PAH and other obliterative vascular diseases.

In response to vascular injury, smooth muscle cells (SMCs)2 exhibit a phenotypic change characterized by loss of contractility and abnormal proliferation, migration, and matrix secretion. This “synthetic” phenotype plays an active role in repair of the vascular damage. Upon resolution of the injury, local environmental signals within the vessel prompt SMCs to reacquire their “contractile” phenotype. SMC phenotype modulation contributes to the pathogenesis of numerous cardiovascular disorders, including PAH, post-angioplasty restenosis and atherosclerosis (1). Idiopathic PAH is a rare disease typically fatal because of right ventricular failure. PAH is characterized by elevated pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary arterial pressure with increased muscularization of small arteries, thickening or fibrosis of the intima, and the presence of plexiform lesions (2, 3). Proliferation and dedifferentiation of SMCs appear to be the major events in the formation of lesions found in pulmonary arteries of patients with PAH (2, 3). Several lines of evidence implicate the BMP pathway in the etiology of PAH. First, heterozygous mutations in the gene encoding BMPRII, the type II subunit of the BMP receptor, were identified in patients with both familial and sporadic PAH (4, 5). Furthermore, the presence of BMPRII mutations in PAH patients curtails the available therapeutic options, as the patients affected are unlikely to demonstrate vasoreactivity and respond to long-term therapy with calcium channel blockers (6, 7). Second, loss of expression of either the type I (8) or the type II subunit (9, 10) of the BMP receptor has been observed in sporadic or secondary forms of PAH. Third, transgenic mice expressing a catalytically inactive BMPRII mutant in SMCs are predisposed to develop PAH in response to different stimuli (11, 12). Fourth, experimental induction of PAH in rodents via hypoxia or monocrotaline injection correlates with a down-regulation of either the type I or the type II BMP receptor and with a general repression of BMP signaling (13–15). Despite these overwhelming correlations, the etiological mechanism of action of the BMP signaling pathway in PAH remains unclear.

BMPs represent the largest group in the transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) superfamily of growth factors (16–18). During embryonic development, the BMP pathway plays multiple essential roles in the induction of ventral mesoderm, cardiac myogenesis, and vasculogenesis (19). Targeted inactivation of the BMP signal transducers Smad1 and Smad5 display a severe vascular phenotype (20). However, the effects of BMPs on adult VSMCs are not completely understood. It has been reported that BMPs inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in serum-starved pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMC) (10, 21). It is also known that BMP7 stimulates the maintenance of the SMC phenotype in aortic SMCs, while BMP2 and BMP4 appear to have opposing effects on expression of SMC-specific genes in VSMCs (22–27). These results suggest that the effects of BMP signaling on VSMCs are complex and possibly dependent on tissue, developmental and experimental variables (28). Here, we characterize the effect of BMP signaling on SMC phenotype modulation and show that BMPs effectively induce a contractile phenotype and up-regulate SMC-specific gene expression in SMCs. The RhoA/Rho kinase (ROCK) pathway is required for SMC differentiation in response to BMP. The BMP pathway activates transcription of SMC genes by inducing nuclear translocation of the transcription factors MRTF-A and MRTF-B, which are known to bind the CArG box found within many SMC-specific gene promoters. Thus, the BMP pathway converges on MRTF-A/B to regulate the differentiation state of vascular SMCs.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and DNA Transfection

PAC-1 (a gift from Dr. Joyce Li) and C3H10T½ cell lines (American Type Culture Collection) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma). These cells were transfected using FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Human primary SMC derived from the pulmonary artery (PASMC), the umbilical artery (UASMC) or the aorta (AoSMC) were purchased from Cambrex and were maintained in Sm-GM2 media (Cambrex). Human SMCs were transfected as described (29). MRTF-A and MRTF-B expression constructs were a gift of Dr. D.-Z. Wang.

Antibodies, Growth Factors, and Inhibitors

The antibodies used in this study were: HA epitope tag (clone Y11, SC-805, Santa Cruz Biotechnology or 12CA5, Roche Applied Science), Myc epitope tag (clone 9E10, Tufts Core facility), anti-smooth muscle α-actin (SMA) (clone 1A4, Sigma), calponin (clone hCP, Sigma), anti-phospho-Smad1/5/8 (Cell Signaling), and anti-MRTF-A (anti-MAL, a kind gift of Dr. Treisman). Recombinant PDGF-BB, human TGFβ1, BMP2, BMP4, and BMP7 proteins were purchased from R&D Systems. The inhibitors used were SB-431542 (Tocris), Y-27632, Wortmannin, LY29400 (Calbiochem), and Latrunculin B (Sigma). Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated phalloidin was purchased from Invitrogen.

Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) Assay

Unless otherwise indicated, cells were treated with 3 nM BMP4 (R&D Systems) in DMEM/0.2% FCS. Total RNA was extracted by TRIzol (Invitrogen) and subjected to reverse transcription using SuperScript II kit (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The products of semi-quantitative PCR were separated on an agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide. Quantitative analysis was performed by real-time PCR (Bio-Rad). The sequence of the PCR primers for human or mouse glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), SMA, calponin, SM22α, smoothelin, Id3, Smad1, and Smad5 is available from the authors upon request.

RNA Interference

Synthetic small interference RNA (siRNA) targeting mouse MRTF-A and MRTF-B was obtained from Dharmacon. Smad1 and Smad5 siRNA Validated Stealth™ DuoPak was from Invitrogen. A siRNA with a non-targeting sequence (scrambled siRNA; Dharmacon) was used as a negative control. The siRNAs were transfected as described before (21). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were treated with BMP4 and harvested.

Luciferase Assay

Luciferase reporter construct containing promoter of SM α-actin (SMA) (−2560/+2784), SM myosin heavy chain (SM-MHC) (−4216/+11795), SM22α (−445/+1st exon), and SM22α with mutations in two CArG boxes were obtained from Drs. G. K. Owens and L. Li; the calponin constructs, wild-type (−549/+1700) or containing mutations in three CArG boxes, were from Dr. J. Miano (30–33). After transfection in 6-well plates, the cells were re-seeded onto 12-well plates and treated with 3 nM BMP4 for 20 h in 0.2% FCS/DMEM. Luciferase assays were carried out as described (34).

Construction of Recombinant Adenovirus and Infection

Adenovirus carrying HA-tagged human constitutively active or dominant negative ALK2, 3, 6, and dominant negative BMPRII were described previously (35, 36). High titer stocks of recombinant viruses were grown in 293 cells and purified. Infection of recombinant adenoviruses was performed at a multiplicity of infection of <8 × 102 pfu/cell. As a control, adenovirus driving β-galactosidase expression was used (Vector Biolabs Inc.).

Immunofluorescence

PASMCs were treated with 3 nM BMP4 for 72 h in SM-GM2. Cells were fixed and permeabilized in 50% acetone/50% methanol solution and subjected to staining using anti-SMA, anti-calponin monoclonal, or anti-HA polyclonal antibodies. Secondary antibodies conjugated with FITC or Alexa Fluor 555 (Invitrogen) were used for detection. Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI, Invitrogen).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was calculated using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Fisher’s Projected Least Significant Difference (LSD) test, or by Student’s t test analysis (p < 0.05), as appropriate. All data are plotted as the mean ± S.E.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay (ChIP)

ChIP assay was performed as described (29). Briefly, cells were transfected with Myc-tagged myocardin, MRTF-A, or MRTF-B expression plasmid. After BMP4 treatment, followed by cross-linking with formaldehyde treatment, genomic DNA was sonicated to an average length of 500 bp. Soluble chromatin was then incubated with either anti-Myc or anti-SRF monoclonal antibody. Immunoprecipitated DNA fragments were amplified and quantitated by real-time PCR with PCR primers specific for the rat SMA gene: 5′-agcagaacagaggaatgcagtggaagagac-3′ and 5′-cctcccactcgcctcccaaacaaggagc-3′.

RESULTS

BMP Signal Is Required for Maintenance of SMC Contractile Markers

Recent studies have shed light on the pathophysiologic pathways that lead to proliferative and obliterative vascular disorders, such as atherosclerosis and PAH. A characteristic change found in atherosclerotic lesions and pulmonary arterioles (PAs) of patients affected by PAH is the loss of the SMC contractile phenotype. To investigate the possible role of BMPs in the maintenance of a differentiated SM phenotype, we examined whether BMP can oppose the decrease of SM markers expression in dedifferentiating human pulmonary artery SM cells (hPASMCs). Prolonged culture of aortic SMCs in growth medium has been shown to lead to a partial dedifferentiation that can be reversed by BMP7 (22). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis shows that human PASMCs express the BMP ligands BMP2–6 (but not BMP7), BMP receptors (ActRI, BMPRIA, BMPRIB, and BMPRII), and downstream signal transducers (Smad1–7) (data not shown) (10). Although PASMCs do not synthesize BMP7, it may be produced by another type of pulmonary cell and subsequently secreted to affect PASMCs (37). Nevertheless, because specific ligand-receptor combinations might transmit different signals to PASMCs, we first tested the role of the PASMC-expressed BMP4 on pulmonary SMCs under the conditions previously used to study BMP7 (22). SMA expression was measured 0, 5 and 8 days after hPASMC cultures had become confluent (Fig. 1A). On day 8, SMA expression level was significantly reduced in cells cultured in growth medium. In contrast, cells cultured in the presence of BMP4 maintained a level of SMA similar to that observed on day 0 (Fig. 1A). Thus, BMP4 prevents reduction of SMA expression in hPASMCs upon prolonged culture under confluent conditions.

FIGURE 1. BMP pathway prevents dedifferentiation of human primary PASMCs.

A, confluent hPAMSCs (passage 5) were cultured in growth media containing 3 nM BMP4 or vehicle. Total RNAs were collected at 0, 5, and 8 days after the treatment and were subjected to RT-PCR analysis of human SMA and GAPDH (loading control). B, hPASMCs at passage 7 (high passage) or passage 4 (low passage) were treated with 3 nM BMP4 or 400 pM TGFβ1 for 72 h in DMEM/0.1% FCS. Cells were then subjected to immunofluorescence staining with FITC-conjugated anti-SMA antibody (green) and nuclear staining with DAPI (blue). C, hPASMCs (passage 5) were treated with 20 ng/ml PDGF-BB and/or 3 nM BMP4 or 400 pM TGFβ1 for 72 h in DMEM/0.1% FCS. Cells were then subjected to immunofluorescence staining with anti-SMA antibodies and nuclear staining with DAPI. D, rat PAC-1 cells were treated with 3 nM BMP4 and/or 100 pM TGFβ1 for 48 h in DMEM/10% FCS. Cells were subjected to immunofluorescence staining with FITC-conjugated anti-SMA antibodies (green) and nuclear staining with DAPI (blue). E, hPASMCs at passage 5 were treated with 20 ng/ml PDGF-BB and/or 3 nM BMP4 or 400 pM TGFβ1 for 72 h in DMEM/0.1% FCS. Total RNAs were prepared from the cells and subjected to semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of SMA and GAPDH (control). Results were normalized to GAPDH expression. F, hPASMCs at passage 5 were treated with 20 ng/ml PDGF-BB and/or 3 nM BMP4 or infection with recombinant adenovirus carrying HA epitope-tagged constitutively active (CA) ALK6 (m.o.i 200). Cells were subjected to immunofluorescence stain with FITC-conjugated anti-SMA antibody (green) and anti-HA antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 555 (for ALK6; yellow) and nuclear stain with DAPI (blue) (top panels). Total cell lysates prepared from hPASMCs treated with or without 3 nM BMP4 for 48 h were subjected to immunoblot with anti-SMA antibody or GAPDH (loading control) (bottom panel). G, hPASMCs at passage 5 were infected with recombinant adenovirus expressing HA-tagged dominant negative (DN) ALK2, ALK3, ALK6, or BMPRII (m.o.i. 200). Cells were subjected to immunofluorescence stain with anti-SMA (green) and anti-HA antibody (for ALK2, 3, 6, and BMPRII; yellow) and nuclear stain with DAPI (blue).

A high number of passages can also result in partial dedifferentiation of primary SMCs (38). We observed reduced levels of SMA protein in hPASMCs at high passage (7 or higher), even if growth-arrested in low-serum medium, compared with low passage hPASMCs (Fig. 1B). Treatment with BMP4 strongly induced SMA expression in high passage PASMCs, while stimulation with TGFβ1 had a weaker effect (Fig. 1B).

An alternative method to induce dedifferentiation of VSMCs in vitro is through stimulation by PDGF (39). PDGF-treated hPASMCs (passage < 5) displayed dramatically reduced SMA immunostaining (Fig. 1C). The presence of BMP4 in the culture medium significantly reduced the level of dedifferentiation induced by PDGF. TGFβ1 could also counteract the effect of PDGF, although less potently than BMP4. In the absence of PDGF, BMP4 or TGFβ1 increased the basal level of SMA staining (Fig. 1C). A similar inhibitory activity on the PDGF effect was observed in PASMCs stimulated with the related factors BMP2 or BMP7 (Supplemental Fig. S1). Furthermore, similar results were obtained using the PAC-1 cell line, derived from rat pulmonary artery SM cells and capable of undergoing a phenotype switch upon serum deprivation or TGFβ treatment (40). Treatment of PAC-1 cells with 3 nM BMP4 induced the expression of SMA, suggesting that the effect of BMP signaling on SM gene expression is neither species-specific nor limited to primary cells (Fig. 1D). Stimulation of PAC-1 cells with TGFβ and BMP4 together induced a synergistic activation of SMA, pointing to a potentially distinct mechanism of induction of SM genes by the TGFβ and BMP4 signaling pathways (Fig. 1D). In agreement with the immunofluorescence data, BMP4 stimulation of PDGF-treated hPASMCs induced SMA mRNA to the level of untreated cells (Fig. 1E).

The BMP4 effect on PASMC can be recapitulated by overexpression of constitutively active (CA) type I BMP receptors. Low-passage, PDGF-treated hPASMCs infected with adenovirus expressing ALK6 (CA) efficiently expressed SMA (Fig. 1F, upper panel). Activated mutants of other BMP type I receptors, such as ALK2 (CA) and ALK3 (CA), also mediated induction of SMA (data not shown). Finally, an increase in SMA protein upon BMP4 stimulation was also detectable by Western blot (Fig. 1F, lower panel). Thus, activation of the BMP pathway prevents hPASMC dedifferentiation caused by three distinct processes: 1) prolonged confluent culture, 2) high passage, and 3) PDGF treatment.

SMCs express BMP ligands, receptors and signal transducers both in vivo and in vitro (10, 21). Therefore, an autocrine BMP signaling loop may contribute to the maintenance of SMC differentiation. To test this hypothesis, hPASMCs were infected with adenovirus expressing dominant negative (DN) BMP type I [ALK2(DN), ALK3(DN), and ALK6(DN)], or type II [BMPRII(DN)] receptors. BMP-induced expression of SMA was blocked by the DN ALK receptors as well as the DN BMPRII (Fig. 1G). Furthermore, the basal level of SMA was also dramatically repressed by the DN-ALKs, indicating that interruption of an autocrine BMP signaling loop may lead to SMC dedifferentiation.

Different BMP Ligands Exhibit a Similar Effect on Expression of SMC-specific Genes in Different Types of SMCs

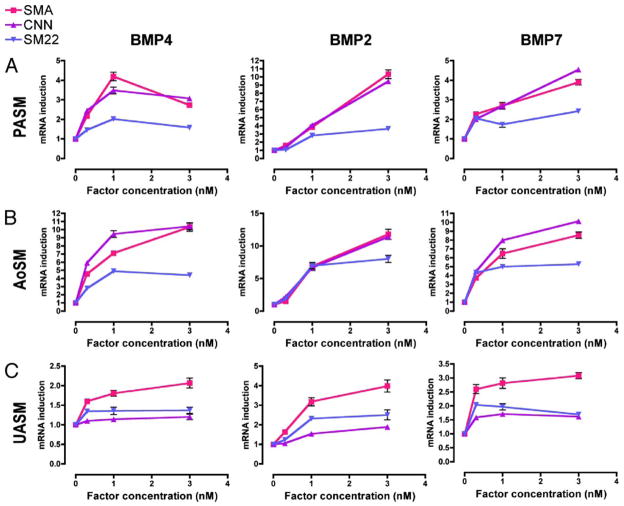

To examine a possible difference in activities of different BMP ligands on the expression of SMC-specific genes, low passage hPASMCs were treated with different concentrations of BMP4, BMP2, or BMP7, followed by RT-PCR analysis of the expression of three SMC-specific markers, SMA, calponin (CNN), and SM22α (SM22) (Fig. 2A). Both BMP2 and BMP7 induced all three SM markers in a dose-dependent manner in a range of concentrations between 0.3 nM and 3 nM, suggesting that induction of SMC genes by BMP is not limited to BMP4 (Fig. 2A). BMP2 induced SMA and CNN about ~10-fold at 3 nM, in comparison with a ~4-fold induction by BMP4 and BMP7 (Fig. 2A). We also examined the BMP effect on SM-marker induction in vascular SMCs of different origin, such as human aortic SMCs (AoSM) and umbilical artery SMCs (UASM) (Fig. 2, B and C). All three BMP ligands strongly induced SMA and CNN in AoSM (Fig. 2B), but triggered a weaker effect in UASM (Fig. 2C). Overall, these results suggest that activation of the BMP pathway by all three BMP ligands tested results qualitatively in an induction of SM markers in vascular SMCs from three different tissues.

FIGURE 2. Induction of SM-markers by BMPs in different vascular SMCs.

Three types of vascular SMCs, hPASMC (A), hAoSM (B), and hUASM (C), were treated with BMP2, BMP4, or BMP7 at different concentrations (0.3–3 nM) in DMEM/0.2% FCS for 24 h. Total RNA was isolated and subjected to RT-PCR analysis using primers for SMA, calponin (CNN), and SM22α (SM22). Relative mRNA expression of each gene was normalized to GAPDH mRNA.

BMP-mediated Activation of SM Genes Is Smad-dependent

Canonical TGFβ/BMP signaling requires receptor-specific signal transducers named Smads, which act as substrates of the type I receptor serine/threonine kinase. Upon phosphorylation, Smad proteins translocate to the nucleus and regulate transcription by binding to a target gene promoter. To examine whether Smads are involved in the activation of SM genes by BMP4, hPASMCs were transfected with siRNAs against the two primary BMP-specific Smad proteins (Smad1 and Smad5) prior to BMP4 stimulation. Compared with mock or control siRNA-transfected cells, transfection of siRNA against Smad1 and Smad5 greatly reduced BMP induction of the SM markers SMA and calponin and of the Smad-dependent gene Id3 (Fig. 3). The residual BMP4 response observed in all three genes may be caused by incomplete repression of Smad1 and Smad5 expression, or to other BMP-specific Smads not targeted by the siRNAs (such as Smad8 and Smad9). These results indicate that BMP-mediated induction of SM genes relies, at least in part, on a Smad-dependent pathway.

FIGURE 3. BMP4 signaling induces SM gene expression in a Smad-dependent manner.

hPASMCs were transfected with a mixture of siRNA against Smad1 and Smad5 (siSmads) or control siRNA (siScr) for 24 h prior to treatment with 3 nM BMP4 for 48 h. Total RNA was isolated and subjected to RT-PCR analysis using primers for SMA, calponin, and the non-SM-specific, BMP-target gene Id3. Relative mRNA expression of each gene was normalized to GAPDH mRNA. The mRNA expression of Smad1 or Smad5 indicates reduction by siRNA.

BMP Signal Induces Expression of SMC-specific Genes

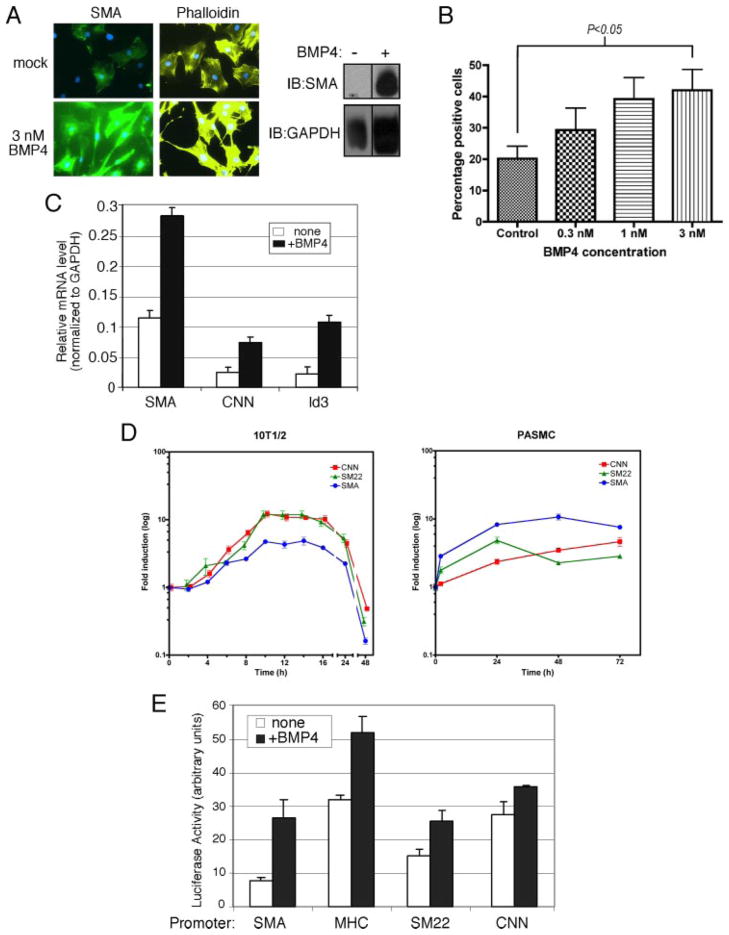

Because BMP signaling maintains SMC differentiation, we hypothesized that it may also induce the differentiation of precursors into a SMC type. It has been reported that TGFβ signaling can induce the expression of SM markers in pluripotent mouse embryonic C3H10T½ (10T½) cells (41–43). We investigated whether BMPs can mimic the effect of TGFβ and supply an instructive signal to 10T½ cells. BMP4 strongly induced expression of the SMC-specific marker SMA and a morphological change toward an elongated SMC-like morphology in 10T½, as detected by immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 4A, left panels) and immunoblot (Fig. 4A, left panel). A robust induction of SMA protein by BMP4 stimulation was observed in both immunofluorescence stain and immunoblot, suggesting that BMP is able to induce SM differentiation in 10T½ cells (Fig. 4A). In the presence of increasing concentrations of BMP4, the number of SMA-positive 10T½ cells gradually increased (Fig. 4B). An induction of mRNAs encoding SMC-specific genes, including SMA and calponin, was measured by quantitative RT-PCR analysis in BMP4-treated 10T½ cells (Fig. 4C). Expression of Id3, a non-SM-specific gene transcription-ally regulated by BMP (44), was monitored as a control. The result underscores the ability of BMP signaling to induce multiple SM markers, including SMA (2.5-fold) and calponin (3.1-fold), alongside Id3 (4.9-fold), in undifferentiated cells (Fig. 4C). A time course of induction of the SM markers SMA, CNN, and SM22 upon BMP4 treatment in 10T½ cells showed a similarly transient pattern of early exponential induction (up to 10 h after stimulation), followed by a plateau and a gradual decrease (between 16 and 48 h after induction) (Fig. 4D, left panel). Interestingly, induction of the same SM markers in PASMC was sustained and followed a different temporal pattern, with the expression of SM22 and SMA peaking at 24 and 48 h, respectively, while CNN continued to increase up to 72 h after induction. Changes occurring in transformed and immortalized cells such as 10T½ may prevent them from acquiring a stable differentiated SM phenotype. Alternatively, SM differentiation inhibitors may also be induced by BMP in 10T½ cells, but not in PASMCs (see “Discussion”).

FIGURE 4. BMP4 induces expression of SMA in non-SMCs.

A, 10T½ cells were treated with 3 nM BMP4 for 72 h in DMEM/10% FCS. Cells were subjected to immunofluorescence staining with FITC-conjugated anti-SMA antibodies (green), Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated phalloidin (yellow), and nuclear staining with DAPI (blue) (left panels). Total cell lysates prepared from 10T½ cells treated with 3 nM BMP4 or vehicle for 48 h were subjected to immunoblot with anti-SMA antibody (right panel) or GAPDH (loading control). B, 10T½ cells were treated with 3 nM BMP4 at 0.3, 1, or 3 nM and subjected to immunofluorescence staining with FITC-conjugated anti-SMA antibodies. SMA-positive cells were counted and are shown as percentage of total cells (n = 100). The increase in number of SMA-positive cells observed upon treatment with 3 nM BMP4 is statistically significant compared with control cells (Student’s t test, p < 0.05). C, 10T½ cells were treated with 3 nM BMP4 in DMEM/0.2% FCS for 24 h. Total RNA was isolated and subjected to RT-PCR analysis using primers for SMA, calponin, and non-SM, BMP4-target gene Id3. Relative mRNA expression of each gene was normalized to GAPDH mRNA. D, 10T½ cells were treated with 3 nM BMP4 for various lengths of time (2– 48 h). Total RNA was isolated and subjected to RT-PCR analysis using primers for SMA, calponin (CNN), and SM22α (SM22). Relative mRNA expression of each gene was normalized to GAPDH mRNA. E, different SM gene promoter (SMA, CNN, SM-MHC, and SM22α)-luciferase reporter constructs were transiently transfected into 10T½ cells as indicated. Cells were treated with or without 3 nM BMP4 for 20 h, followed by luciferase assay.

The induction of several SM-specific mRNAs within 4 h after BMP4 treatment raises the possibility of a direct transcriptional activation of SM-specific genes by BMP4. To explore this possibility, 10T½ cells were transfected with luciferase reporter constructs driven by SMC-specific promoters from the SMA, SM-myosin heavy chain (MHC), SM22α, and CNN genes. All four promoters were activated by BMP4, suggesting that the BMP signal elicits a direct transcriptional activation of SMC-specific promoters in 10T½ cells (Fig. 4E).

BMP-mediated Induction of SMC Genes Is ROCK-dependent but TGFβ Receptor-independent

TGFβs are known modulators of VSMC growth and differentiation (41–43) and can directly induce the expression of SMC markers. Therefore, BMPs might stimulate SMC differentiation indirectly by inducing the expression of TGFβ ligands, or otherwise activating the TGFβ type I receptors. This model was tested by treating hPASMCs with a specific inhibitor of the type I TGFβ receptor kinases (SB-431542) (45) prior to BMP4 or TGFβ1 stimulation, followed by immunostaining for SMA (Fig. 5A). SB-431542 treatment effectively blocked the TGFβ1-mediated induction of SMA, but did not inhibit SMA induction by BMP4, suggesting that BMP induces SMA independently of the TGFβ pathway.

FIGURE 5. Involvement of the RhoA/ROCK pathway in the regulation of SMA by BMP4.

A, hPASMCs were treated with specific inhibitor of the type I TGFβ receptor kinase (SB-431542) prior to 3 nM BMP4 or 100 pM TGFβ1 stimulation, followed by immunostaining with FITC-conjugated anti-SMA antibody (green) and nuclear stain with DAPI (blue). B, 10T½ cells were transfected with the SMA-luciferase reporter. Cells were infected with adenovirus expressing constitutively active RhoA [RhoA (CA)], dominant negative RhoA [RhoA (DN)] or vehicle for 24 h, then treated with 3 nM BMP4 for 48 h with or without 10 μM ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) and assayed for luciferase activity. C, hPASMCs were treated with increasing concentrations (100 nM–10 μM) of PI-3K inhibitor (Wortmannin) or ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632), with or without 3 nM BMP4 for 48 h, followed by immunostaining with FITC-conjugated anti-SMA antibody (green) and nuclear stain with DAPI (blue).

The Rho GTPases RhoA, Cdc42, and Rac1 are important regulators of cytoskeletal remodeling (46, 47). RhoA signaling is known to affect contractility of pulmonary SMCs from rats with chronic PAH (48), and play a general role in maintenance of SMC differentiation (49). To examine a possible role of RhoA in SMC differentiation upon BMP treatment, 10T½ cells transfected with the SMA promoter-luciferase reporter were treated with a specific inhibitor of Rho-associated kinases (ROCK), Y-27632 (50), and then exposed to BMP4 (Fig. 5B). Treatment with Y-27632 significantly reduced the BMP-mediated induction of the reporter in 10T½ cells (Fig. 5B). Similarly, expression of dominant negative RhoA [Rho (DN)] by adenovirus infection strongly inhibited both basal and induced transcription of the reporter, while constitutively active RhoA [RhoA (CA)] increased the basal level without affecting significantly BMP stimulation (Fig. 5B). Similar results were obtained in hPASMCs. When these cells were treated with increasing concentrations of ROCK inhibitor Y-27632, BMP4-mediated induction of SMA was decreased in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast, the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI-3K) inhibitors Wortmannin (Fig. 5C) and LY-29400 (data not shown) had no effect on BMP-induced SMA activation. These results indicate that activation of the RhoA/ROCK pathway in response to BMP4 stimulation is essential for expression of the SMA gene in both non-SMCs and SMCs.

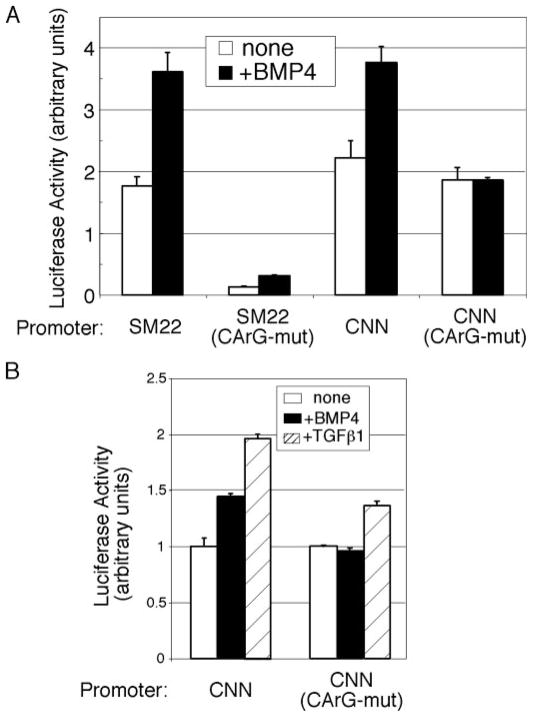

Activation of SM Genes by the BMP Signaling Pathway Is CArG Box-dependent

DNA-binding proteins such as serum response factor (SRF) regulate transcription of SMC-specific genes (51, 52). SRF, in association with its cofactors, binds a specific DNA sequence called the CArG box [CC(AT)6GG] and activates transcription (52). To test whether the BMP pathway regulates SMC gene transcription through the CArG element, SM22α or calponin promoter-luciferase reporter constructs, with or without mutations in the CArG sequences, were transfected into 10T½ cells (Fig. 6A). Mutation in the CArG elements decreased (SM22α) or abolished (calponin) the BMP-dependent activation of these reporters, suggesting that the BMP pathway acts, at least in part, through regulation of CArG box binding factors (Fig. 6A). BMP4-dependent activation of a CArG-mutated calponin reporter construct was also completely abolished in PAC-1 cells, indicating that the requirement of a functional CArG box for BMP stimulation is not cell type-specific (Fig. 6B). In agreement with previous reports (53), the CArG box-mutated calponin promoter was still partially inducible by TGFβ1 stimulation, confirming that TGFβ regulates the calponin promoter through a cis-acting element other than the CArG box (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that the CArG box is specifically required for BMP-mediated transcriptional activation of calponin.

FIGURE 6. BMP-mediated transcriptional activation of SM gene is CArG box-dependent.

A, 10T½ cells were transfected with wild-type or mutant SM22α or calponin reporter constructs, which are mutated in the CArG box sequence as indicated, treated with BMP4, and assayed for luciferase activity. B, PAC-1 cells were transfected with wild-type or mutant calponin reporter constructs, which are mutated in the CArG box sequence as indicated, treated with 3 nM BMP4 or 100 pM TGFβ1 and assayed for luciferase activity.

Involvement of the SRF Cofactors MRTF-A and MRTF-B in the Regulation of SM Genes by BMP

The CArG sequence binds to a complex of transcription factors comprising SRF and its coactivators, such as myocardin, MRTF-A (also called MAL, MKL-1, and MSAC), or MRTF-B (also called MKL-2) (51). Unlike myocardin, which is expressed only in the cardiovascular system and is absent in 10T½ cells, MRTF-A and MRTF-B are widely expressed (54, 55), raising the possibility that they may be involved in mediating the CArG-dependent BMP stimulation of SMC-specific promoters in 10T½, and possibly primary SMCs (51). Furthermore, the MRTFs have been proposed to mediate SMC phenotype regulation by the RhoA pathway (56), making them also good candidates as effectors of the ROCK-dependent BMP stimulation of the SMC phenotype. Transfection of 10T½ cells with the SMA-reporter construct and increasing amounts of MRTF-A showed a gradual stimulation of both basal and BMP-induced transcription (Fig. 7A). The increase of basal activity of the SMA-reporter at higher amounts of MRTF-A is possibly caused by protein overexpression, which causes localization of some MRTF-A in the nucleus (Fig. 7A). Thus, MRTF-A is able to amplify the activation of the SMA promoter in response to BMP4 in 10T½ cells, suggesting that the intracellular concentration of MRTF-A is a limiting factor for BMP stimulation of SMA transcription. MRTF-B was also able to induce the SMA-reporter upon BMP stimulation, but with an overall weaker activity compared with MRTF-A, which might be caused by a difference in the intrinsic transcription activation potential between MRTF-A and MRTF-B (55) (Supplemental Fig. S2).

FIGURE 7. BMP4 signal mediatesarecruitmentofcofactorMRTFstoSMApromoter.

A,10T½ cellsweretransfected with SMA-reporter constructs and increasing amounts of Myc-MRTF-A expression plasmid (1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 ng) and assayed for luciferase activity. B, total RNAs were extracted from 10T½ cells transfected with siRNA against MRTF-A or MRTF-B or non-targeting (control) siRNA and were subjected to RT-PCR analysis to examine expression of MRTF-A or MRTF-B mRNA. RNA levels were quantified by real-time PCR analysis with normalization to GAPDH expression. C, 10T½ cells transfected with MRTF-A or MRTF-B siRNAs, or non-targeting (control) siRNA, together with the SMA reporter construct. The luciferase activity was measured after treating cells with or without 3 nM BMP4 for 48 h. There is no statistically significant change in the SMA reporter activity in cells transfected with MRTF-A siRNA, unlike cells transfected with control siRNA or MRTF-B siRNA (Student’s t test, n.s. represents p > 0.05). D, 10T½ cells transfected with siRNAs as in panel C, and treated with or without 3 nM BMP4 or 400 pM TGFα1, followed by immunostaining with FITC-conjugated anti-SMA antibody (green) and nuclear stain with DAPI (blue). As negative control, non-targeting siRNA was used. E, 10T½ cells were transiently transfected with Myc-MRTF-A expression plasmid. After being treated with 3 nM BMP4, 20% serum, or BMP4 and Latrunculin B (LB), an inhibitor of actin polymerization, cells were subjected to immunostaining with FITC-conjugated anti-Myc antibody (green) and nuclear stain with DAPI (blue). The cells in which MRTF-A localization was predominantly nuclear were counted and compared as percentage to the total number of cells. F, 10T½ cells were transfected with Myc-tagged myocardin-856 (smooth muscle isoform), MRTF-A, or MRTF-B and treated with 3 nM BMP4 for 24 h. Cells were then subjected to ChIP assay. A recruitment of these cofactors to the SMA promoter was examined by immunoprecipitation with an anti-Myc antibody, followed by quantitative real time-PCR analysis using primers specific for the SMA promoter. As control, untransfected cells were subjected to the ChIP assay using anti-Myc or anti-SRF antibody, followed by PCR using the same primers. An average of triplicate experiments is presented. The data show induction of SMA chromatin binding by BMP4 compared with cells treated with vehicle. In the inset, data are normalized to the background signal observed with the anti-Myc antibody immunoprecipitation in untransfected cells. The amount plotted in the input bar is 1:60 of the total used for each immunoprecipitation.

To investigate the requirement of MRTF-A and MRTF-B for the BMP-mediated regulation of SMA expression, 10T½ cells were transfected with siRNA directed against MRTF-A or MRTF-B. The specificity of the siRNA duplexes was confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR analysis of MRTF-A and MRTF-B mRNAs in siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 7B). 10T½ cells treated with MRTF-A siRNA showed a dramatic reduction in both SMA reporter activity (Fig. 7C) and SMA staining after BMP4 stimulation (Fig. 7D). The MRTF-B siRNA had no effect on SMA reporter activity compared with the effect of MRTF-A siRNA (Fig. 7C), but it markedly reduced the BMP-mediated expression of endogenous SMA gene expression (Fig. 7D), possibly reflecting a different ability of MRTF-B to activate episomal versus genome-embedded promoters. Consistent with the observation that the CArG box mutant calponin reporter is still partially responsive to TGFβ treatment (Fig. 6B), the TGFβ-induced expression of SMA was only weakly affected by MRTF-A or MRTF-B siRNAs (Fig. 7D). These results suggest that both MRTF-A and MRTF-B are essential for the BMP-mediated activation of SMA in 10T½ cells.

Nuclear Translocation of MRTF-A Mediated by BMP Signaling

To examine the potential mechanism of regulation of MRTF-A by BMP signaling, the subcellular localization of transfected Myc epitope-tagged MRTF-A in response to BMP4 treatment was examined by immunofluorescence in 10T½ cells. Myc-MRTF-A was predominantly localized in the cytoplasm (86% cytoplasmic localization) in cells grown in low-serum conditions (Fig. 7E, Control). In the presence of BMP4, MRTF-A translocated to the nucleus (66.4% nuclear) with an efficiency comparable to that achieved in high serum (56% nuclear), a condition that has been previously reported to stimulate nuclear localization of MRTF-A (Fig. 7E) (57). When cells were treated with both BMP4 and Latrunculin B, an inhibitor of actin polymerization, nuclear localization of MRTF-A was reduced (Fig. 7E, BMP4+LB), suggesting an important role of actin stress fibers for the translocation of MRTF-A (57). Latrunculin B also inhibits MRTF-A nuclear translocation upon stimulation of the RhoA pathway (57), providing further evidence of the requirement of a functional RhoA-dependent pathway for BMP-mediated induction of the SMC phenotype.

We examined whether MRTF-A, which is translocated to the nucleus upon BMP stimulation, is recruited to the CArG element of the SMA promoter by ChIP assay. 10T½ cells transfected with expression plasmids encoding Myc epitope-tagged myocardin, MRTF-A or MRTF-B were treated with BMP4 prior to Ch-IP with an anti-Myc antibody. Myocardin was constitutively recruited to the SMA promoter when overexpressed (Fig. 7F). Unlike myocardin, recruitment of MRTF-A and MRTF-B to the SMA promoter was strongly augmented by BMP4 stimulation (Fig. 7F). No MRTFs were recruited to the myocardin-independent CArG element of the c-fos promoter, with or without BMP stimulation (data not shown). These results suggest that nuclear translocation of MRTF-A or MRTF-B by BMP4 stimulation leads to their recruitment to the SMC-specific CArG box and results in transcriptional activation.

DISCUSSION

The phenotypic switch of SMCs from a quiescent, “contractile” state to a proliferative “synthetic” state has been shown to play a key role in the repair of tissue damage and in the development of a variety of human SMC-linked diseases, including asthma, restenosis, atherosclerosis, and arterial hypertension. It is known that the phenotypic switch is caused by coordinate repression/activation of transcription of SMC-specific genes, such as SMA, SM22α, calponin, and SM-MHC. However, the mechanisms that regulate this process are not well understood. In this study, we report that the BMP signaling pathway induces SMC-specific genes by recruiting the members of the myocardin family of transcription factors MRTF-A and MRTF-B to SMC gene promoters. As MRTF-A is ubiquitously expressed in SMCs as well as non-SMCs (55), we speculate that BMP-mediated induction of SMC genes might be involved not only in maintenance of SMCs at a mature differentiated stage, but also in switching myofibroblasts and vascular SM precursor cells from a “synthetic” to a “contractile” state during vascular injury and repair.

Cross-talk between BMP and TGFβ Signals

Both BMPs and TGFβs are synthesized and secreted from vascular SMCs and endothelial cells. TGFβ directly inhibits SMC proliferation and migration and stimulates the expression of contractile SMC markers (39). However, little is known about the role of the BMP signaling pathway in the modulation of the SMC phenotype (22, 27). TGFβ is a potent inducer of SMC gene transcription, partially through a cis-acting sequence (TGFβ control element, or TCE) to which TCE-binding transcription factor (s) are recruited, and partially though the CArG box (53). BMP4 appears to activate SMC genes through the CArG box by recruiting CArG-binding factors, SRF and MRTFs. In a typical SMC-specific promoter, such as that of the SMA gene, a TCE (−42) and two CArG boxes (−62 and −113) are found in close proximity (53). In PAC-1 cells, BMP4 and TGFβ synergize for SMA gene induction (Fig. 1D). This is the first evidence showing cross-talk between BMP and TGFβ pathways in the regulation of smooth muscle cell physiology. We speculate that the synergistic effect of TGFβ and BMP4 in the regulation of SMA might be caused by cooperation among transcription factors recruited to the TCE and the CArG box. It was reported that the TGFβ-specific signal transducer Smad3, in complex with myocardin, binds, and stimulates the SM22α promoter in a CArG-independent manner in response to TGFβ stimulation (58). We found that the responsiveness to BMP4 of the CArG mutant SM22α reporter was reduced but not completely abolished, raising the possibility that also the BMP pathway may be able to activate the SM22α promoter in part via a CArG-independent mechanism.

Additional Indirect Effects of BMPs

Long-term maintenance of the SM phenotype by BMPs may also be partially indirect, involving the transcriptional or post-transcriptional regulation of proteins/RNAs that modulate SM genes expression. Transcription regulation via the CArG box and its binding factors is subject to repression by a variety of corepressor proteins. For example, the hairy-related transcription factor 2 (HRT-2) (59) and GATA factors (60) associate with myocardin and repress its activity by an unknown mechanism. The four and half LIM protein 2 (FHL2) interacts with SRF, competes with MRTFs for SRF binding and represses SMC-specific gene transcription (61). Therefore, the BMP signal might negatively regulate the activity or the expression of these negative regulators, a hypothesis currently under investigation. Also, Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) was identified as a factor induced in response to vascular injury and able to repress myocardin expression and block association of the SRF/myocardin complex to the CArG box (62). It is interesting to speculate that the decrease of expression of SM markers at 48 h after BMP stimulation in 10T½ cells (Fig. 4C) could be the consequence of an induction or accumulation of KLF4 upon BMP treatment. We indeed observed an induction of KLF4 mRNA after BMP4 treatment (Supplemental Fig. S3), but it is yet unclear whether KLF4 induction is the primary cause of reduced expression of SM markers at later time points of BMP stimulation in 10T½ cells.

Canonical and Non-canonical BMP Pathways

We showed that MRTFs were translocated to the nucleus and recruited to a SM gene promoter in response to BMP4 stimulation. BMP-specific signal transducers Smad1 and Smad5 are partially required for SM genes activation by BMP4, and it is possible that they may be directly involved in the recruitment of MRTFs to the SMC-specific promoters. It has been reported that Smad1 and myocardin as a complex synergistically activate cardiomyocyte-specific genes through the CArG sequence in response to BMP2 stimulation in COS7 cells (63). Furthermore, neonatal rat cardiomyocytes treated with BMP2 increase myocardin expression (63). However, in the course of this study we observed that (a) overexpression of Smad1 did not further increase the BMP-mediated activation of an SMC-specific reporter, and (b) no recruitment of Smad1 to the SMA promoter was detected by Ch-IP assay (data not shown). Thus, the canonical Smad pathway does not appear to explain all the effects of BMPs on SM cells, raising the possibility that an alternative pathway, possibly linked to a non-transcriptional role of Smads, might play an important role in the regulation of MRTFs and SMC differentiation.

Mechanism of MRTF Translocation

It has been shown that the subcellular localization of MRTFs, which is responsible for regulation of SRF activity and SMC-specific gene expression, is sensitive to actin dynamics (57). Several regulatory mechanisms were proposed for this process. When actin filaments (F-actins) are destabilized, MRTFs are sequestered in the cytoplasm by direct binding to actin monomers (G-actins) via the N-terminal RPEL motifs. On the contrary, when members of the Rho family (RhoA, Cdc42, and Rac1) or the downstream kinase ROCK are activated, actin polymerization is stabilized. The increase in the F-actin/G-actin ratio triggers a release of MRTFs from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and activation of SM gene promoters. More recently, an F-actin-binding protein named Striated Muscle Activator of Rho Signaling (STARS) was found to promote nuclear translocation of MRTFs and activate SRF in a Rho-dependent manner. It is possible that molecules of the BMP signaling pathway, such as the BMP receptor kinase, might act through proteins similar to STARS or directly modulate the RPEL motifs of MRTFs in response to BMP4 and induce nuclear translocation. It is also possible that the nuclear translocation of MRTFs is a direct consequence of an increase in the F-actin/G-actin ratio through activation of the Rho/ROCK pathway by BMP signaling. The exact mechanism of regulation of the Rho/ROCK pathway by BMP4, however, will be the subject of a future study.

Role of the BMPRII C-terminal Domain

Several proteins were shown to associate with the C-terminal region of the cytoplasmic, non-enzymatic, “tail” domain of BMPRII (BMPRII-TD), including LIM kinase 1 (LIMK1) (64, 65). The association of LIMK1 with BMPRII-TD modulates the catalytic activity of LIMK1. The exact mechanism of regulation of LIMK1 by BMPRII-TD is yet to be studied. LIMK1 is known to phosphorylate ADF/cofilin and block actin de-polymerization (66). Therefore, it is plausible that the regulation of nuclear localization of MRTFs upon BMP4 stimulation is, at least in part, caused by a change in LIMK1 activity, possibly a stimulation of LIMK1 and stabilization of actin filaments. Some of the mutations in the BMPRII gene associated with PAH cause truncation of the BMPRII-TD, which might result in dysregulation of the interaction with LIMK1 or other BMPRII-TD-binding proteins. The characteristics of pathological changes found in the pulmonary arterioles of PAH patients include dedifferentiation of SMC phenotype in the media as well as proliferation and fibrosis of the intima. It is interesting to speculate the existence of a pathway by which down-regulation of LIMK1 activity in PASMCs as a result of truncation of the BMPRII-TD triggers a decrease in F-actin/G-actin ratio and causes cytoplasmic accumulation of MRTFs and reduction of SMC-specific gene expression. BMPRII-TD is also known to interact with dynein light chain Tctex1 (67), a microtubule motor protein; it is possible that BMPRII, in association with Tctex1, might be directly involved in transport of MRTFs or other proteins required for the regulation of SM gene expression.

Potential Role of ALK1

In addition to the existing link between BMPRII mutations and PAH, defects in the genes encoding endoglin and the activin-like receptor kinase 1 (ALK1) have been found in families with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) (68). ALK1 belongs to the family of type I TGFα/BMP receptors and is expressed in vascular cells. A subset of HHT patients with ALK1 mutations develop severe PAH (69), implicating a similarity between the function of the ALK1 and BMP pathways in VSMCs. The recent discovery of ligands of ALK1 belonging to the BMP family (BMP-9 and BMP-10) lends further support to this hypothesis (70).

Dual Effects of BMPs

A phenotype change of VSMC from a differentiated to a dedifferentiated state can lead to vascular calcification during the onset and progression of atherosclerosis, and the BMP pathway has been proposed as a mediator of the calcification process (71, 72). It is interesting to speculate that formation of atherosclerotic lesions might involve two phases: an initial down-regulation of the BMP signal, causing dedifferentiation, followed by an up-regulation of BMP signaling, which may favor calcification. The TGFα pathway is well characterized for its opposing, sequential actions during tumor progression, both as tumor suppressor and as tumor promoter (73). This is likely caused by the context-dependence of the cellular response to growth factors, where the competence of the receiving cell to the incoming stimulus greatly affects the type of response triggered. Similarly, VSMCs in slightly different SMC phenotype stages or growth environments might interpret BMP signals differently, triggering different biological outcomes, such as dedifferentiation or calcification. Supporting evidence for this model comes from a report published during the preparation of this report, in which Hayashi et al. (74) implicate BMP signaling in the dedifferentiation of vascular SMCs (VSMCs) through a mechanism involving the induction of Msx1 and Msx2 expression, which then compete with the myocardin/SRF complex for binding to the CArG box and thus inhibit expression of SMC-specific genes. Although apparently inconsistent with our findings, the conclusions drawn by Hayashi et al. can be reconciled with ours considering that, in their studies, Hayashi et al. (74, 75) use rat primary VSMCs cultured on laminin in media supplemented with insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), a cytokine that strongly activates the expression of SMC-specific genes and induces differentiation of VSMCs. An equivalent pro-differentiation effect of BMPs might be difficult to detect under their conditions. Conversely, the system employed by Hayashi et al. might be ideal for detecting down-regulation of SM genes and dedifferentiation of SM cells. Thus, we speculate that the different response to BMP signaling observed by Hayashi et al. might be due to different initial stages of smooth muscle phenotype at the time of BMP treatment. Consistently with this hypothesis, we did not find that the Msx genes are activated by BMP4 in human PASMCs in our recent comprehensive microarray analysis, while simultaneously SMC-specific genes such as SMA, smoothelin, calponin, and SM-MHC were strongly induced upon BMP4 stimulation (data not shown). Furthermore, we were unable to detect by real-time RT-PCR an induction of Msx1 or Msx2 mRNAs by BMP4 treatment in PASMCs (see Supplemental Fig. S3). Interestingly, we detected a stable ~2/3-fold induction of Msx1 in 10T½ cells (Supplemental Fig. S3), which may help explain, together with the induction of KLF4, the mechanism by which BMP-mediated induction of SM genes in 10T½, but not PASMCs, declines after 48 h. On the contrary, tissue- or species-specific effects cannot explain the differences between these studies, because we also examined the effect of BMP signals in VSMCs from other mammals, such as mouse and rat aortic SMCs, and non-vascular SMCs (human myometrial SMCs), and found induction of SM genes in these cells similar to PASMCs under our culture condition.3 Finally, it is conceivable that, depending on context, the same growth factor may be involved in both differentiation and dedifferentiation of SM cells. Further study is required to clarify the mechanism of this potential responsiveness switch.

In conclusion, our study sheds light on a fundamental role of BMP signaling during maintenance of arterial homeostasis and repair of vascular damage, and delineates a novel signaling response that may be amenable to a targeted pharmacological treatment of vascular disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Li Li, Joyce Li, Eric N. Olson, Gary K. Owens, and Joseph Miano for sharing reagents.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NHLBI (National Institutes of Health) (to A. H.) and the American Heart Association (to G. L.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

The abbreviations used are: SMC, smooth muscle cell; TGF, transforming growth factor; DMEM, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium; FCS, fetal calf serum; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation assay; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; PASMC, pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells; BMP, bone morphogenetic factor; HA, hemagglutinin; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; SMA, smooth muscle α-actin.

References

- 1.Owens G. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:487–517. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.3.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubin LJ, Rich S. Primary Pulmonary Hypertension. Marcel Dekker, Inc; New York, NY: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Runo JR, Loyd JE. Lancet. 2003;361:1533–1544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Machado RD, Pauciulo MW, Thomson JR, Lane KB, Morgan NV, Wheeler L, Phillips JA, 3rd, Newman J, Williams D, Galie N, Manes A, McNeil K, Yacoub M, Mikhail G, Rogers P, Corris P, Humbert M, Donnai D, Martensson G, Tranebjaerg L, Loyd JE, Trembath RC, Nichols WC. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:92–102. doi: 10.1086/316947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomson JR, Machado RD, Pauciulo MW, Morgan NV, Humbert M, Elliott GC, Ward K, Yacoub M, Mikhail G, Rogers P, Newman J, Wheeler L, Higenbottam T, Gibbs JS, Egan J, Crozier A, Peacock A, Allcock R, Corris P, Loyd JE, Trembath RC, Nichols WC. J Med Genet. 2000;37:741–745. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.10.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elliott CG, Glissmeyer EW, Havlena GT, Carlquist J, McKinney JT, Rich S, McGoon MD, Scholand MB, Kim M, Jensen RL, Schmidt JW, Ward K. Circulation. 2006;113:2509–2515. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.601930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puri A, McGoon MD, Kushwaha SS. Nat Clin Pract. 2007;4:319–329. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du L, Sullivan CC, Chu D, Cho AJ, Kido M, Wolf PL, Yuan JX, Deutsch R, Jamieson SW, Thistlethwaite PA. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:500–509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atkinson C, Stewart S, Upton PD, Machado R, Thomson JR, Trembath RC, Morrell NW. Circulation. 2002;105:1672–1678. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012754.72951.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang S, Fantozzi I, Tigno DD, Yi ES, Platoshyn O, Thistlethwaite PA, Kriett JM, Yung G, Rubin LJ, Yuan JX. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L740–L754. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00284.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beppu H, Ichinose F, Kawai N, Jones RC, Yu PB, Zapol WM, Miyazono K, Li E, Bloch KD. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L1241–L1247. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00239.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long L, MacLean MR, Jeffery TK, Morecroft I, Yang X, Rudarakanchana N, Southwood M, James V, Trembath RC, Morrell NW. Circ Res. 2006;98:818–827. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000215809.47923.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishimura T, Vaszar LT, Faul JL, Zhao G, Berry GJ, Shi L, Qiu D, Benson G, Pearl RG, Kao PN. Circulation. 2003;108:1640–1645. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000087592.47401.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi H, Goto N, Kojima Y, Tsuda Y, Morio Y, Muramatsu M, Fukuchi Y. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;290:L450–L458. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00206.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morty RE, Nejman B, Kwapiszewska G, Hecker M, Zakrzewicz A, Kouri FM, Peters DM, Dumitrascu R, Seeger W, Knaus P, Schermuly RT, Eickelberg O. Arteriol Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1072–1078. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.141200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Attisano L, Wrana JL. Science. 2002;296:1646–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1071809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heldin CH, Miyazono K, ten Dijke P. Nature. 1997;390:465–471. doi: 10.1038/37284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massagué J. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:753–791. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogan BLM. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1580–1594. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moser M, Patterson C. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94:713–718. doi: 10.1160/TH05-05-0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lagna G, Nguyen PH, Ni W, Hata A. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L1059–L1067. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00180.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dorai H, Vukicevic S, Sampath TK. J Cell Physiol. 2000;184:37–45. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200007)184:1<37::AID-JCP4>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrell NW, Yang X, Upton PD, Jourdan KB, Morgan N, Sheares KK, Trembath RC. Circulation. 2001;104:790–795. doi: 10.1161/hc3201.094152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakaoka T, Gonda K, Ogita T, Otawara-Hamamoto Y, Okabe F, Kira Y, Harii K, Miyazono K, Takuwa Y, Fujita T. J Clin Investig. 1997;100:2824–2832. doi: 10.1172/JCI119830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newman JH, Trembath RC, Morse JA, Grunig E, Loyd JE, Adnot S, Coccolo F, Ventura C, Phillips JA, 3rd, Knowles JA, Janssen B, Eickelberg O, Eddahibi S, Herve P, Nichols WC, Elliott G. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:33S–39S. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willette RN, Gu JL, Lysko PG, Anderson KM, Minehart H, Yue T. J Vasc Res. 1999;36:120–125. doi: 10.1159/000025634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King KE, Iyemere VP, Weissberg PL, Shanahan CM. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11661–11669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bobik A. Arterio Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1712–1720. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000225287.20034.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ku M, Howard S, Ni W, Lagna G, Hata A. J Biol Chem. 2005;281:5277–5287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L, Liu Z, Mercer B, Overbeek P, Olson EN. Dev Biol. 1997;187:311–321. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mack CP, Owens GK. Circ Res. 1999;84:852–861. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.7.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madsen CS, Regan CP, Hungerford JE, White SL, Manabe I, Owens GK. Circ Res. 1998;82:908–917. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.8.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miano JM, Carlson MJ, Spencer JA, Misra RP. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9814–9822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hata A, Seoane J, Lagna G, Montalvo E, Hemmati-Brivanlou A, Massague J. Cell. 2000;100:229–240. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81561-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fujii M, Takeda K, Imamura T, Aoki H, Smapath TK, Enomoto S, Kawabata M, Kato M, Ichijo H, Miyazono K. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3801–3813. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishihara A, Watabe T, Imamura T, Miyazono K. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3055–3063. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-02-0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ying Y, Zhao GQ. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:1781–1786. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.6.1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chamley-Campbell J, Campbell GR, Ross R. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:1–61. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Owens GK, Kumar MS, Wamhoff BR. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:767–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deaton RA, Su C, Valencia TG, Grant SR. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31172–31181. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504774200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grainger DJ. Arterio Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:399–404. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000114567.76772.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo J, Sartor M, Karyala S, Medvedovic M, Kann S, Puga A, Ryan P, Tomlinson CR. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;194:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Misiakos EP, Kouraklis G, Agapitos E, Perrea D, Karatzas G, Boudoulas H, Karayannakos PE. Eur Surg Res. 2001;33:264–269. doi: 10.1159/000049716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hollnagel A, Oehlmann V, Heymer J, Ruther U, Nordheim A. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19838–19845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inman GJ, Nicolas FJ, Callahan JF, Harling JD, Gaster LM, Reith AD, Laping NJ, Hill CS. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:65–74. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown JH, Del Re DP, Sussman MA. Circ Res. 2006;98:730–742. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000216039.75913.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tzima E. Circ Res. 2006;98:176–185. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000200162.94463.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nagaoka T, Gebb SA, Karoor V, Homma N, Morris KG, Mc-Murtry IF, Oka M. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:996–1002. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01028.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rolfe BE, Worth NF, World CJ, Campbell JH, Campbell GR. Atherosclerosis. 2005;183:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Narumiya S, Ishizaki T, Uehata M. Methods Enzymol. 2000;325:273–284. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)25449-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Teg Pipes GC, Creemers EE, Olson EN. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1545–1556. doi: 10.1101/gad.1428006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miano JM. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:577–593. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hautmann MB, Madsen CS, Owens GK. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10948–10956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mercher T, Coniat MB, Monni R, Mauchauffe M, Khac FN, Gressin L, Mugneret F, Leblanc T, Dastugue N, Berger R, Bernard OA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5776–5779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101001498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang DZ, Li S, Hockemeyer D, Sutherland L, Wang Z, Schratt G, Richardson JA, Nordheim A, Olson EN. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14855–14860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222561499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hinson JS, Medlin MD, Lockman K, Taylor JM, Mack CP. Am J Physiol. 2007;292:H1170–H1180. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00864.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miralles F, Posern G, Zaromytidou AI, Treisman R. Cell. 2003;113:329–342. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qiu P, Ritchie RP, Fu Z, Cao D, Cumming J, Miano JM, Wang DZ, Li HJ, Li L. Circ Res. 2005;97:983–991. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000190604.90049.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nakagawa O, Nakagawa M, Richardson JA, Olson EN, Srivastava D. Dev Biol. 1999;216:72–84. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Proweller A, Pear WS, Parmacek MS. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8994–9004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413316200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Philippar U, Schratt G, Dieterich C, Muller JM, Galgoczy P, Engel FB, Keating MT, Gertler F, Schule R, Vingron M, Nordheim A. Mol Cell. 2004;16:867–880. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu Y, Sinha S, McDonald OG, Shang Y, Hoofnagle MH, Owens GK. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9719–9727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Callis TE, Cao D, Wang DZ. Circ Res. 2005;97:992–1000. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000190670.92879.7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Foletta VC, Lim MA, Soosairajah J, Kelly AP, Stanley EG, Shannon M, He W, Das S, Massague J, Bernard O. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:1089–1098. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee-Hoeflich ST, Causing CG, Podkowa M, Zhao X, Wrana JL, Attisano L. EMBO J. 2004;23:4792–4801. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Niwa R, Nagata-Ohashi K, Takeichi M, Mizuno K, Uemura T. Cell. 2002;108:233–246. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00638-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Machado RD, Rudarakanchana N, Atkinson C, Flanagan JA, Harrison R, Morrell NW, Trembath RC. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:3277–3286. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van den Driesche S, Mummery CL, Westermann CJ. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;58:20–31. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00852-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Abdalla SA, Gallione CJ, Barst RJ, Horn EM, Knowles JA, Marchuk DA, Letarte M, Morse JH. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:373–377. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00085504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.David L, Mallet C, Mazerbourg S, Feige JJ, Bailly S. Blood. 2007;109:1953–1961. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-034124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Iyemere VP, Proudfoot D, Weissberg PL, Shanahan CM. J Intern Med. 2006;260:192–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Johnson RC, Leopold JA, Loscalzo J. Circ Res. 2006;99:1044–1059. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000249379.55535.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Massague J, Blain SW, Lo RS. Cell. 2000;103:295–309. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hayashi K, Nakamura S, Nishida W, Sobue K. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:9456–9470. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00759-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hayashi K, Takahashi M, Kimura K, Nishida W, Saga H, Sobue K. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:727–740. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.4.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.