Abstract

The probiotic lactic acid bacterium Lactobacillus plantarum is a potential delivery vehicle for mucosal vaccines because of its generally regarded as safe (GRAS) status and ability to persist at the mucosal surfaces of the human intestine. However, the inherent immunogenicity of vaccine antigens is in many cases insufficient to elicit an efficient immune response, implying that additional adjuvants are needed to enhance the antigen immunogenicity. The goal of the present study was to increase the proinflammatory properties of L. plantarum by expressing a long (D1 to D5 [D1-D5]) and a short (D4-D5) version of the extracellular domain of invasin from the human pathogen Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. To display these proteins on the bacterial surface, four different N-terminal anchoring motifs from L. plantarum were used, comprising two different lipoprotein anchors, a transmembrane signal peptide anchor, and a LysM-type anchor. All these anchors mediated surface display of invasin, and several of the engineered strains were potent activators of NF-κB when interacting with monocytes in cell culture. The most distinct NF-κB responses were obtained with constructs in which the complete invasin extracellular domain was fused to a lipoanchor. The proinflammatory L. plantarum strains constructed here represent promising mucosal delivery vehicles for vaccine antigens.

INTRODUCTION

Lactobacilli belong to the lactic acid bacteria (LAB), which are indigenous organisms in a variety of ecological niches, including vegetables, meat, dairy products, and the human gastrointestinal tract (53). These organisms have been ingested for centuries and are regarded as safe for human consumption. In addition, some strains of lactobacilli have documented health benefits and are marketed as probiotics (6). Over the past decade, there has been an increasing interest in developing lactobacilli as mucosal delivery vehicles for a wide range of therapeutic and prophylactic proteins (64). The mucosal surfaces represent the major portal of entry for pathogens, and it has been shown that it is possible to induce both systemic and mucosal immune responses via these surfaces (5). Promising results have been obtained with mucosal delivery of vaccine antigens through the intranasal, oral, or genital mucosal surfaces by both commensal and attenuated pathogenic bacteria (62). There has been much focus on vaccine delivery by attenuated pathogenic bacteria because of their intrinsic immunostimulatory properties, but such strains could potentially regain their virulence and, also, confer a risk to immunocompromised individuals (18). While commensal strains are considered a safer alternative, they may lack the potentially beneficial immunostimulatory properties of pathogens. It has been claimed, however, that certain lactobacilli have intrinsic immunomodulatory properties (63).

The probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1, the first Lactobacillus sequenced, is a human saliva isolate that has been successfully exploited as a vaccine delivery vehicle (13, 25). Still, the use of nonpathogenic bacteria such as L. plantarum in immunization strategies usually does not result in complete protection against the disease, suggesting that vaccine adjuvants are needed to boost the immune response generated by the antigen-expressing bacteria (62). Early studies with LAB have shown that both systemic and mucosal immune responses improve substantially upon coexpression of adjuvants, such as interleukin-12 (IL-12) and IL-6, with an antigen (4, 60). Recently, novel strategies have been employed to increase the immunogenicity of mucosal vaccine antigens—in particular, coexpression of proteins from pathogenic bacteria that target immune cells in the gut (14, 47). Antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs), are promising target cells in this context. These cells are able to detect microbes and present antigenic structures from these to T cells, thus eliciting adaptive immune responses (56).

The immunogenicity of an antigen is significantly influenced by its final cellular location (cytoplasmic, secreted, or anchored in or to the cell wall) in the bacterial delivery vector, and several studies have shown that surface anchoring of the antigen results in the highest antigen immunogenicity (3, 51). In the case of lactobacilli, there are several ways to anchor proteins to the extracellular surface, including lipid-mediated N-terminal anchoring to the cell membrane, N-terminal anchoring to the cell membrane mediated by a noncleaved N-terminal signal peptide (SP), C-terminal sortase-mediated covalent anchoring to the cell wall, and noncovalent anchoring through the presence of additional domains that interact with the cell wall, such as LysM domains. While the sortase-mediated route has been explored quite extensively (12, 23, 35, 42), other routes have received less attention (19).

In keeping with the above-mentioned considerations, the goal of the present study was to increase the proinflammatory properties of L. plantarum for vaccine delivery by expressing invasin from the enteropathogenic bacterium Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Invasin is a multidomain virulence factor, consisting of a 500-amino-acid transmembrane domain and a 497-residue extracellular 5-domain structure (domains D1 to D5 [D1-D5]), forming an extended rod-like structure (28). The protruding C-terminal domains are important for the interaction of invasin with its receptor (D5 appears at the outer end of the rod and includes the C terminus of the protein [28]). Invasin promotes the uptake of Y. pseudotuberculosis by M cells in the gut through binding to β1-integrins exposed on the M cell surface, thereby targeting the bacterium to the lymphatic tissues (11). In addition, invasin is capable of initiating proinflammatory host cell reactions by activation of the innate immune system (7, 21, 26). To study whether invasin could have similar effects in L. plantarum, a full-length form (D1-D5, referred to as Inv) and a truncated form (D4-D5, referred to as InvS) of its extracellular domain were expressed and N-terminally anchored to the bacterial surface.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, cell lines, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli TOP10 cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom) at 37°C with shaking. L. plantarum cells were grown statically in MRS (Oxoid) broth at 37°C. Solid media were prepared by adding 1.5% (wt/vol) agar to the broth. The plasmid constructions were first established in E. coli cells and then transformed into L. plantarum cells. The antibiotic concentrations used were 5 μg/ml and 200 μg/ml erythromycin for L. plantarum and E. coli, respectively.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| L. plantarum WCFS1 | Host strain | 38 |

| E. coli TOP10 | Host strain | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR-Blunt II TOPO | 3.5-kb cloning vector for PCR fragments; Kanr | Invitrogen |

| pLp_2588sAmyA | Emr; pSip401 derivative (58) containing the inducible PsppA promoter translationally fused to a gene construct encoding the Lp_2588 signal peptide followed by AmyA | 45 |

| pEV | Emr; pLp_2588sAmyA derivative where the Lp_2588-AmyA cassette has been removed (control plasmid, “empty vector”) | This study |

| pLp_1261Inv | Emr; pLp_2588sAmyA derivative where the Lp_2588-AmyA cassette has been replaced by the lipoanchor sequence from lp_1261 fused to part of the inv gene encoding the 492 C-terminal residues of invasin (domains D1 to D5) | This study |

| pLp_1261InvS | Emr; like pLp_1261Inv, but encoding only the 190 C-terminal residues of invasin (domains D4 and D5) | This study |

| pLp_1452Inv | Emr; like pLp_1261Inv, but with the lipoanchor from Lp_1452 instead of the lipoanchor from Lp_1261 | This study |

| pLp_1452InvS | Emr; like pLp_1261InvS, but with the lipoanchor from Lp_1452 instead of the lipoanchor from Lp_1261 | This study |

| pLp_1568InvS | Emr; pLp_2588sAmyA derivative where the Lp_2588-AmyA cassette has been replaced by a cassette encoding C-terminally truncated Lp_1568 fused to domains D4 and D5 of invasin; for N-terminal signal peptide-based anchoring of invasin | This study |

| pLp_3014Inv | Emr; pLp_2588sAmyA derivative where the Lp_2588-AmyA cassette has been replaced by a cassette encoding Lp_3014 fused to domains D1 to D5 of invasin; for anchoring through an N-terminal LysM domain | This study |

| pLp_3014InvS | Emr; like pLp_3014Inv, but encoding only the 190 C-terminal residues of invasin (domains D4 and D5) | This study |

DNA manipulations and plasmid construction.

DNA manipulations were performed essentially as previously described (54). The primers used in this study were purchased from Operon Biotechnologies GmbH (Cologne, Germany) and are listed in Table 2. Genomic DNA from L. plantarum overnight colonies was obtained by lysing the cells in a microwave oven at maximum intensity for 2 min. The cell lysate was used directly, i.e., without any further DNA purification, as the template in subsequent PCRs using hot start KOD polymerase (Toyobo, Japan). Amplified PCR fragments were separated on 1% agarose gels and purified using the NucleoSpin extract II kit (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co., Düren, Germany). PCR fragments were cloned into restriction-digested plasmids using the In-Fusion HD cloning kit (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA), following the manufacturer's instructions. Plasmid DNA was purified from E. coli using the NucleoSpin plasmid kit (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co). L. plantarum was transformed by electroporation according to a previously described method (33). The DNA sequences of all PCR amplicons were verified by sequence analyses.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| 1261F | GGAGTATGATTCATATGAATTTCAAAACAGCTGCAA |

| 1261R | GTCGACCGCCGCAATCGTGCCCCCGTTCTTACCGAGACGGT |

| 1452F | GGAGTATGATTCATATGAAGAAATGGCTCATTGCC |

| 1452R | GTCGACCGCCGCAATCGTGCCTTGAACCGTGACTTTAGGTTCGT |

| 1568F | GGAGTATGATTCATATGAAATTGTTTAAGAAAATTACGATAAAT |

| 1568R | CGGTCAGCGTGTCGACCGCTGCATAAATTTGCTTAGCA |

| 3014F | GGAGTATGATTCATATGAAAAAACTTGTAAGTACAATCGTAACT |

| 3014R | CGGTCAGCGTGTCGACAAGGGCCCAAGCAGCCAT |

| TInvF | CATATGAGCGTCACCGTTCAGCAGC |

| TInvR | GAATTCTTATATTGACAGCGCACAGAGC |

| InvF | CGGGGGCACGATTGCGGCGGTCGACAGCGTCACCGTTCAGCAGC |

| InvSF | CGGGGGCACGATTGCGGCGGTCGACACGCTGACCGGTATTCTGGT |

| InvR | CCGGGGTACCGAATTCTTATATTGACAGCGCACAGAGC |

Underlining indicates 15-bp extensions that are complementary to the ends of the NdeI-EcoRI-digested p2588sAmyA vector. Such overlap is necessary for In-Fusion cloning (In-Fusion HD cloning kit). Boldface indicates primer extensions necessary for fusing anchor and Inv fragments by splicing by overlap extension (SOE)-PCR. NB: there are four nonoverlapping nucleotides in the InvF-1452R pair, but this does not affect the correctness of the final PCR product (as confirmed by sequencing).

All expression constructs used in this study (Table 1 and Fig. 1) are derivatives of pSIP401, a member of the pSIP400 vector series developed for inducible gene expression in lactobacilli (58, 59) and further developed for secretion and C-terminal anchoring of proteins (23, 45). For practical reasons, a previously described pSIP401 variant called pLp_2588AmyA (45) was used as a starting point. Initially, a 1,476-bp fragment from the inv gene corresponding to the extracellular part of the invasin protein (492 C-terminal residues, domains D1-D5) was amplified from the Y. pseudotuberculosis chromosome (the genomic DNA was a kind gift from G. Kapperud at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health) using the primers TInvF and TInvR. The amplicon was subcloned into the pCR-Blunt II-TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the protocol provided by the supplier. The inv fragment was reamplified from the pCR-Blunt II-TOPO vector using the primer pair InvF/InvR, and a 225-bp fragment corresponding to the 75 N-terminal amino acids from Lp_1261 was amplified with the primer pair 1261F/1261R. These fragments (with 25 overlapping base pairs) were subsequently mixed and fused together in a splicing by overlap extension-PCR (SOE-PCR) reaction (29) using the primers 1261F and InvR. By using this approach, a 7-residue linker (encoded by GGC ACG ATT GCG GCG GTC GAC, corresponding to the amino acid residues GTIAAVD) was introduced between Lp_1261 and Inv. This linker encodes a 5-residue loop naturally found between domains D1 and D2 in the invasin protein followed by a SalI restriction site (encoding VD). The Lp1261-Inv fragment was subsequently In-Fusion cloned into NdeI-EcoRI-digested pLp_2588AmyA (45), yielding the plasmid pLp_1261Inv. A plasmid encoding a shorter version of Inv (190 C-terminal residues, domains D4-D5), pLp_1261InvS, was constructed using the same strategy, except that the InvS fragment was amplified with the primer pair InvSF/InvR. Using the same strategy, the Inv and InvS fragments were also fused downstream to a fragment from lp_1452 (corresponding to the 142 N-terminal residues of the protein, amplified using the primers 1452F and 1452R). The resulting 1452-Inv and 1452-InvS fragments were subsequently In-Fusion cloned into NdeI-EcoRI-digested pLp_2588AmyA, yielding the plasmids pLp_1452Inv and pLp_1452InvS, respectively.

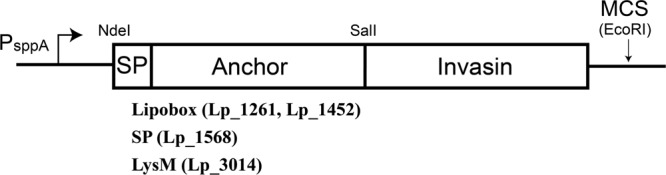

Fig 1.

Schematic overview of the expression cassette for N-terminal anchoring of invasin in L. plantarum. The vectors are based on previously described secretion vectors (19) in which the cassette is translationally fused to the inducible PsppA promoter. All parts of the cassette are easily exchangeable using the introduced restriction sites: the NdeI site at the translational fusion point, the SalI site between the N-terminal anchor and invasin, and the downstream multiple cloning site (MCS, including EcoRI). Three principally different N-terminal anchoring motifs were used, all containing a signal peptide (SP) for secretion: two different lipoanchors were generated using lipobox fragments from Lp_1261 and Lp_1452, one transmembrane anchor was generated by fusing invasin to C-terminally truncated Lp_1568, which contains an SP but no signal peptide cleavage site, and one LysM anchor was generated by fusing invasin to Lp_3014.

The Inv and InvS fragments were further fused to Lp_3014 from L. plantarum for noncovalent, N-terminal anchoring. This gene product is a putative transglycosylase that binds the peptidoglycan in the cell wall through an N-terminal LysM domain (65). All 612 bp from the lp_3014 open reading frame (corresponding to 204 residues) were amplified with the primer pair 3014F/3014R and In-Fusion cloned into NdeI-SalI-digested pLp_1452InvS, resulting in the plasmid pLp_3014InvS. To construct pLp_3014Inv, the pLp_1452Inv vector was digested with SalI and EcoRI, and the resulting Inv fragment was cloned into SalI-EcoRI-digested pLp_3014InvS.

Vectors encoding Inv and InvS anchored by an N-terminal transmembrane anchor were constructed using Lp_1568, an N-terminally anchored penicillin binding protein from L. plantarum with a putative uncleaved signal peptide. A 2,013-bp fragment from lp_1568 (corresponding to the complete protein with a 7-residue C-terminal truncation) was amplified with the primer pair 1568F/1568R and subsequently In-Fusion cloned into the NdeI-SalI-digested pLp_1452InvS vector, resulting in the plasmid pLp_1568InvS. Despite numerous attempts, a variant of this plasmid with the full-length invasin was not obtained.

Finally, a plasmid lacking an open reading frame was constructed for use as a negative control. The sticky ends of the NdeI-EcoRI-digested pLp_2588sAmyA plasmid were made blunt by incubation with Phusion polymerase (New England BioLabs, Inc., Ipswich, MA) and 10 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate for 10 s at 72°C. The blunted, linearized plasmid was recircularized by incubation with T4 DNA ligase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) overnight at 15°C, yielding the plasmid pEV. All plasmids were transformed into E. coli TOP10 cells before electroporation into L. plantarum WCFS1.

Antisera.

Polyclonal antibodies against invasin were ordered from ProSci (Poway, CA) and generated by immunizing rabbits with synthetic invasin peptides (804NGQNFATDKGFPKT817 and 942YSSDWQSGEYWVKK955). Three production bleeds were taken after the immunization of the animals, of which the third bleed was used in all experiments.

Harvesting of invasin-expressing cells.

To analyze invasin production, L. plantarum cells harboring the constructed plasmids were diluted in MRS to a cell density with an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼0.1 from an overnight culture and incubated for approximately 2 h at 37°C, after which invasin expression was induced with 25 ng/ml peptide pheromone as described elsewhere (27). Two hours after induction, 8 × 109 CFU of bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation at 7,000 × g for 2 min at 4°C, and the resulting cell pellets were washed once in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Flow cytometry and indirect immunofluorescence microscopy of invasin-expressing L. plantarum.

Approximately 1 × 108 harvested cells were resuspended in 300 μl PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (PBS-B) and 40 μl rabbit antiserum (containing anti-invasin polyclonal antibodies). After incubation at room temperature (RT) for 30 to 60 min, the bacteria were centrifuged at 7,000 × g for 2 min at 4°C and washed five times with 500 μl PBS five times. The cells were subsequently incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Jackson ImmunoResearch, PA) diluted 1:200 in PBS-B for 30 to 60 min at room temperature. After collecting the bacteria by centrifugation at 7,000 × g for 2 min and washing with 500 μl PBS-B five times, staining was analyzed by flow cytometry using a MACSQuant analyzer (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), following the manufacturer's instructions. For indirect immunofluorescence microscopy, the bacteria were visualized under a Leica SP5 confocal scanning laser microscope using a 488-nm argon laser (FITC photomultiplier tube [PMT]) and a bright field (BF) PMT for transmitted light (Leica Microsystems, GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany).

Cell lines.

U937 cells stably transfected with the NF-κB reporter plasmid 3x-κB-luc (9) (a kind gift from Rune Blomhoff) were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (PAA Laboratories GmbH, Pasching, Austria) containing 1% nonessential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 50 μM thioglycerol, 25 μg/ml gentamicin (Garamycin), and 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco Life Technologies, Paisley, United Kingdom). Cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2.

NF-κB reporter assay.

U937 cells were cultivated in the presence of 75 μg/ml hygromycin for 24 h before seeding. Amounts of 3 × 104 cells in 80 μl of medium were seeded per well in a white 96-well plate (Nunc, Rochester, NY). L. plantarum cells harboring the invasin expression plasmids were grown, induced, and harvested as described above. Approximately 8 × 109 cells were resuspended in 300 μl PBS and exposed to UV light for 15 min at RT, after which the attenuated bacteria were collected by centrifugation at 7,000 × g for 1.5 min at RT. Subsequently, 2 × 107 bacteria or 1 μg/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was added to the wells. After 6 h of incubation in a humidified incubator at 37°C, the luciferase activity of the cells was assayed by using the Bright-Glo luciferase assay system according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Promega, WI).

Statistical analyses.

Quantitative experimental data come from triplicate experiments and are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SD). Where relevant, statistically significant differences (P < 0.01) were determined by using unpaired t tests.

RESULTS

Surface display of invasin in L. plantarum.

To display invasin from Y. pseudotuberculosis on the surface of L. plantarum, the pSIP vector system previously developed for protein secretion and C-terminal cell wall anchoring (23, 44, 45) was further developed for N-terminal anchoring, as shown schematically in Fig. 1. N-terminal anchoring is necessary to orient the C-terminal β1-integrin binding domains of invasin distal to the L. plantarum cell surface. To achieve N-terminal anchoring, signals from two lipoproteins (Lp_1261 and Lp_1452), one protein with an uncleaved signal peptide acting as an N-terminal transmembrane anchor (Lp_1568), and a cell surface protein with a LysM anchoring motif (Lp_3014) were exploited. Lp_1261 and Lp_1452 are predicted to encode the oligopeptide ABC transporter OppA and the peptidylprolyl isomerase PrsA, respectively (65), which are anchored to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane through an N-terminal, lipid-modified cysteine residue (30). The Inv-encoding gene fragments were fused to 75-residue and 142-residue N-terminal fragments, respectively, approximately corresponding to the regions upstream of the catalytic domains as predicted by Pfam (22). Lp_1568 is predicted to encode the penicillin binding protein 2B, which is inserted into the plasma membrane through its signal peptide, which lacks a signal peptidase (SPase) cleavage site (65). Lp_3014 is a putative extracellular transglycosylase with a cleavable signal peptide and an N-terminal LysM domain according to SignalP (52) and Pfam (22). The LysM domain is a widespread protein motif in Gram-positive bacteria, which mediates noncovalent binding to the peptidoglycan in the cell wall (8). In the case of Lp_3014 and Lp_1568, the invasin fragments were fused to the essentially complete L. plantarum protein.

Two versions of invasin were fused to the anchor sequences. The longer version, referred to as Inv, comprises all five extracellular domains, D1 to D5, of this protein (28), whereas the shorter version, InvS, comprises the C-terminal D4 and D5 domains only. It was anticipated that InvS might have a lower probability of causing secretion problems in L. plantarum, because of its smaller size. This strategy led to the construction of a total of seven plasmids encoding invasin destined for surface display in L. plantarum (the eighth construct, pLp_1568Inv, was never obtained; see Materials and Methods for details).

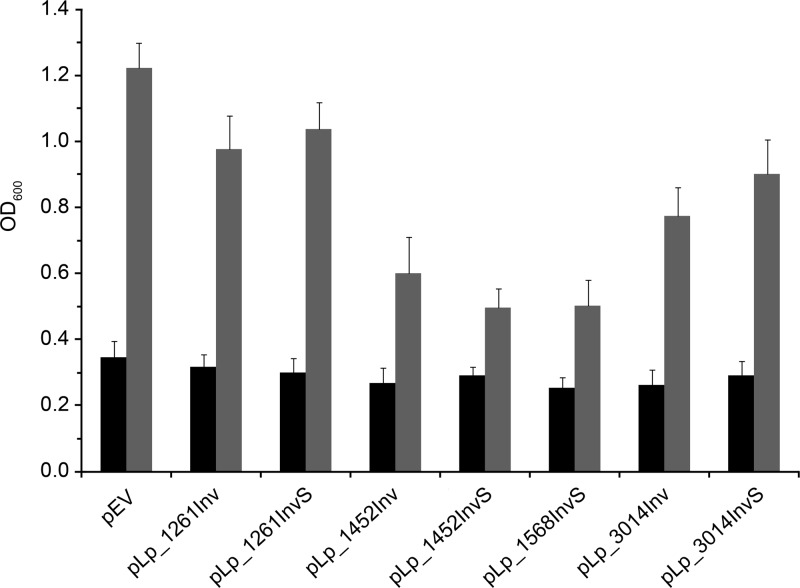

The presence of constructs for invasin expression affected the growth rate of the L. plantarum host strain to various extents (Fig. 2). Strains harboring plasmids with Lp_1452- or Lp_1568-derived anchors showed clearly reduced growth, indicating that overproduction of these chimeric proteins confers significant stress on the production host. On the other hand, strains harboring Lp_1261- or Lp_3014-derived anchors showed only slightly reduced growth.

Fig 2.

Cell growth of invasin-expressing L. plantarum strains. OD600 values were measured at the induction point (black bars) and 2 h after induction (gray bars). The data are means from triplicate experiments and presented as the means ± SD.

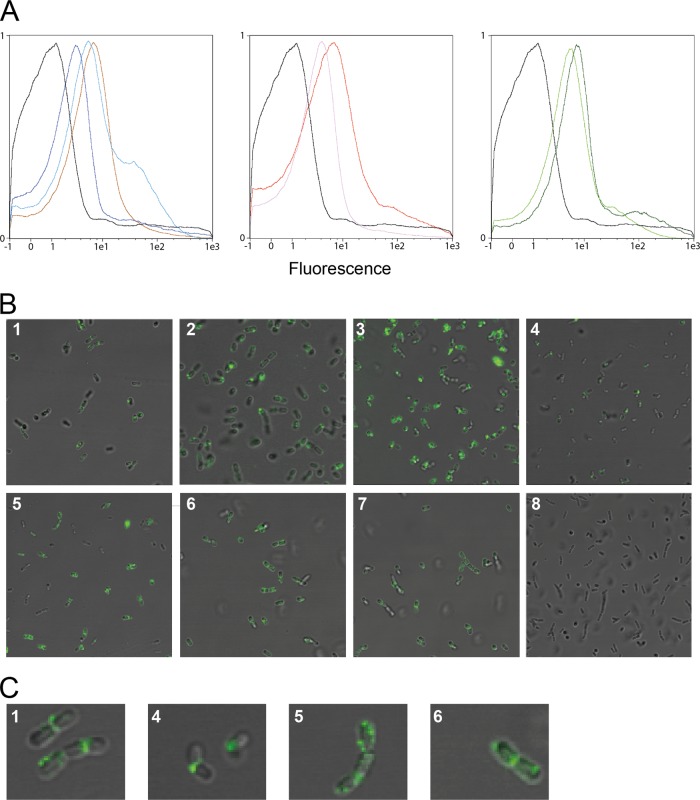

Flow cytometry analyses showed a clear shift in the fluorescence signal compared to that of the control strain, confirming that all tested anchors mediate surface expression of invasin (Fig. 3A). Immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3B) confirmed surface localization and revealed an uneven distribution of the fluorescence signal, which appears strongest at the septum and at distinct focal patches (Fig. 3C).

Fig 3.

Surface localization of invasin in modified L. plantarum cells. (A and B) Representative flow cytometric (A) and microscopic (B) analyses of L. plantarum cells harboring plasmids designed for N-terminal surface anchoring of invasin. The cells were probed with rabbit anti-invasin polyclonal antibody and, subsequently, FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies. The L. plantarum strains are denoted by different colors in the flow cytometry histograms and different numbers in the micrographs. L. plantarum harboring a vector without the inv gene was used as negative control (pEV, black, 8) and is depicted in all three flow cytometry histograms. L. plantarum strains harboring the following invasin-encoding plasmids are shown: pLp_1261Inv (light blue, 1), pLp_1261InvS (dark blue, 2), pLp_1452Inv (pink, 3), pLp_1452InvS (red, 4), pLp_1568InvS (brown, 5), pLp_3014Inv (green, 6), and pLp_3014InvS (dark green, 7). (C) Magnifications of representative cells depicted in panel B: pLp_1261Inv (1), pLp_1452InvS (4), pLp_1568InvS (5), and pLp_3014Inv (6).

Invasin displayed on the L. plantarum surface stimulates NF-κB-activated luciferase expression in human monocytes.

Seven invasin-producing L. plantarum strains were then evaluated for their capacity to activate NF-κB in the monocytic cell line U937. This cell line is stably transfected with an NF-κB reporter plasmid, meaning that the production of luciferase is induced upon activation of NF-κB (9). The innate immune response is the first line of defense against invading microorganisms. NF-κB regulates a wide variety of proinflammatory genes, including cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules which play critical roles in innate immune responses (40). Previous studies on invasin from Yersinia enterocolitica, which shows 73% sequence identity with invasin from Y. pseudotuberculosis, have shown that activation of NF-κB is mediated by invasin's ability to bind to β1-integrins on the surface of epithelial cells (55). The presence of β1-integrins on the U937 cells was verified by flow cytometry using β1-integrin-recognizing anti-CD29-FITC antibody (CD29 corresponds to β1-integrin), and this experiment showed that virtually all U937 cells were CD29 positive (results not shown).

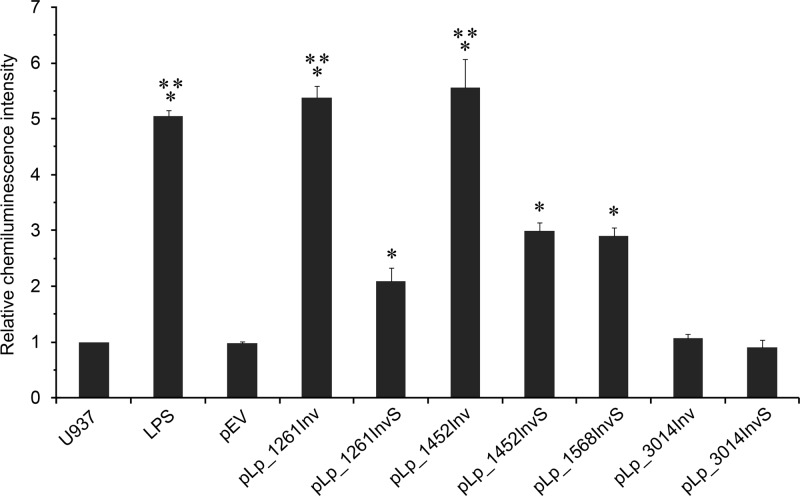

The activation experiments were performed by coincubation of invasin-producing bacteria, harvested 2 h after induction, and the monocytic cell line U937, followed by detection of NF-κB-activated luciferase expression by chemiluminescence (Fig. 4). This revealed clear differences between the various strains. Compared to U937 cells alone or U937 cells incubated with bacteria harboring the empty vector, bacteria harboring pLp_1261Inv, pLp_1261InvS, pLp_1452Inv, pLp_1452InvS, and pLp_1568InvS induced statistically significant higher levels of chemiluminescence. Of these, bacteria harboring pLp_1261Inv and pLp_1452Inv induced levels that were significantly higher than the levels induced by the other positive strains, pLp_1261InvS, pLp_1452InvS, and pLp_1568InvS, and that were similar to the level obtained with the positive control, bacterial LPS. Both of these best-performing strains produce the complete 5-domain extracellular domain of invasin. In contrast, incubation of U937 cells with L. plantarum harboring pLp_3014Inv or pLp_3014InvS did not yield chemiluminescence signals that were distinguishable from the background.

Fig 4.

NF-κB-directed luciferase expression in monocytes. Various L. plantarum cells were coincubated with U937 monocytes stably transfected with a plasmid (3x-κB-luc) encoding a NF-κB-inducible luciferase gene (9). The intensities of the resulting luciferase-generated chemiluminescence signals were measured, and relative values are shown as the ratio of results for individual samples and the negative control (U937). The data come from triplicate experiments and are presented as the means ± SD. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.01) compared to the results for L. plantarum/pEV are denoted by an asterisk (*). Signals labeled with two additional asterisks (**) are significantly stronger (P < 0.01) than the signals labeled with only one asterisk. LPS, bacterial lipopolysaccharides (positive control).

DISCUSSION

In recent years, substantial research efforts on LAB as in situ vaccine delivery vehicles have generated promising results. These vehicles are regarded as safe for human use but tend to suffer from insufficient immune responses directed toward the antigen, especially in oral delivery (39). Ways to circumvent this include codelivery of adjuvants (4, 34) or targeting of the bacteria to relevant cells of the immune system, e.g., using dendritic cell-binding peptides (48). Another option is to target so-called antigen-sampling microfold (M) cells, which cover underlying mucosal lymphoid tissue and represent a promising portal for mucosal vaccine delivery (32). In contrast to intestinal epithelial cells, M cells can take up microorganisms or antigens from the intestinal lumen and deliver them to the mucosal immune system in the lamina propria, leading to an enhanced immune response (2). Some pathogens, such as the human pathogen Y. pseudotuberculosis, exploit this route to more efficiently enter the body while at the same time suppressing the immune response. Y. pseudotuberculosis targets M cells by expressing invasin that binds β1-integrins exposed on the surface of M cells (31, 43). Interestingly, invasin binding to β1-integrins induces proinflammatory responses in epithelial cells, including activation of NF-κB and production of proinflammatory chemokines (36, 55, 61). Based on this knowledge, the idea behind the present study was that display of invasin on the surface of L. plantarum could mimic early infection characteristics of Y. pseudotuberculosis and thereby confer increased adjuvant properties on this probiotic organism. It has previously been shown that the D4 and D5 domains are sufficient for invasin binding to β1-integrins, albeit with a reduced efficiency compared to the 5-domain D1-D5 version (17).

Anchoring of heterologous proteins to LAB surfaces using LPXTG-type C-terminal anchors for covalent linkage to the cell wall has been quite extensively explored (12, 20, 23, 35, 42). Likewise, the use of LysM domains to promote noncovalent association of proteins to LAB cell walls is well documented (1, 46). However, only a very few reports exist on N-terminal anchoring of heterologous proteins in lactobacilli, and these are often based on the use of non-self anchoring signals (16, 41). Interestingly, work on Bacillus subtilis has shown that a cellulase could be anchored by fusing it to PrsA, which is the homologue of Lp_1452. This strategy resulted in efficient targeting of the cellulase to the cytoplasmic membrane, but in contrast to the results presented here, the enzyme was not exposed to the extent that it could be detected by flow cytometry of intact cells (37).

All N-terminal anchors tested in this study, comprising two lipoproteins (Lp_1261 and Lp_1452), one protein containing an uncleaved signal peptide functioning as an N-terminal transmembrane anchor (Lp_1568), and one LysM-containing protein (Lp_3014), led to surface display of invasin as shown by flow cytometry and immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the immunofluorescence microscopy data showed that invasin is unevenly distributed on the L. plantarum cell surface. This is not uncommon for surface proteins, and it has been shown that such distinct expression patterns could be directed by the nature of the signal peptide (10). All signal peptides used for surface localization of invasin are predicted to direct secretion through the SecYEG channel (50), but no experimental evidence for signal peptide-mediated localized protein secretion in lactobacilli is currently available.

The invasin-expressing L. plantarum strains differed with respect to their ability to activate NF-κB-induced luciferase expression in β1-integrin-expressing monocytes (Fig. 4), despite the fact that invasin was detected on the surface of all strains (Fig. 3). Bacteria expressing Inv surface targeted by the lipoproteins Lp_1261 and Lp_1452 were clearly the most potent NF-κB activators, followed by InvS anchored by Lp_1261, Lp_1452, and Lp_1568. The data for the Lp_1261 and Lp_1452 constructs clearly show that InvS is less efficient than Inv when it comes to NF-κB activation. Importantly, this difference shows that NF-κB activation is most likely mediated by the invasin molecule and not by other components on the L. plantarum surface, such as overproduction of the Lp_1261 and Lp_1452 lipoprotein fragments themselves. In contrast to InvS, Inv contains the D2 domain, which is important for invasin functionality and efficient β1-integrin binding (17). Somewhat surprisingly, Inv anchored by Lp_3014 did not significantly activate NF-κB. Notably, the Lp_3014 constructs create a fundamentally different way of anchoring, where Inv is associated with the cell wall rather than linked to the cell membrane via an inserted lipid or transmembrane peptide anchor. More generally, it should be noted that while similar amounts of bacterial cells were used in the experiments and while all cells clearly express invasin (Fig. 3), there still may be differences between the experiments due to variation in the number of exposed proteins per cell.

It is generally recognized that activation of NF-κB in monocytes promotes differentiation into activated macrophages, so-called M1 macrophages, which are associated with a proinflammatory T helper 1 immune response (24, 57). Interestingly, the activation of NF-κB observed for the L. plantarum strain expressing Lp_1261 lipoanchored invasin was quantitatively similar to the NF-κB activation by LPS from Gram-negative bacteria, which is known to induce differentiation of monocytes into M1 macrophages (49). Thus, L. plantarum expressing lipoanchored Inv seems to have acquired the desired proinflammatory properties. Attempts to demonstrate the ability of invasin-expressing L. plantarum cells to invade Caco-2 cells were not successful (data not shown; the usefulness of Caco-2 cells as a model system for M cells has been demonstrated in previous studies on invasin-expressing E. coli [15]). Dersch and Isberg (17) have previously shown that multimerization of invasin promotes efficient cell internalization. It is conceivable that that the multimerization efficiency of invasin on the L. plantarum surface was too low, either due to too-low protein densities or sterical hindrances.

In conclusion, the current study shows that L. plantarum surface proteins with three fundamentally different N-terminal anchoring motifs are able to target invasin from Y. pseudotuberculosis to the L. plantarum cell surface. Furthermore, the data show that the displayed invasin had adjuvant activity in several of the engineered strains. Although the study does not present a systematic study of the suitability of various N-terminal anchoring options, the results so far do indicate that hitherto hardly explored lipoanchoring is both feasible and promising. For the particular purpose of this study, the Lp_1261 lipoanchor worked best, since the strain containing pLp_1261Inv yielded maximum NF-κB activation (Fig. 4) while being among those with the lowest impairment in growth rate (Fig. 2). Lipoanchors like Lp_1261 may provide an important expansion of the toolbox for surface targeting of proteins. Surface expression of invasin by L. plantarum could provide the tipping point for skewing a tolerogenic immune response in a proinflammatory direction, thereby increasing antigen immunogenicity. Due to their adjuvant properties, the L. plantarum strains constructed in this study represent promising mucosal vaccine delivery vehicles. Studies on coexpression of invasin and antigens are currently in progress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Georg Kapperud at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health for genomic DNA from Yersinia pseudotuberculosis YPIII.

This work was funded by Norwegian Research Council grants 183637 and 196363.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 15 June 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Audouy SA, et al. 2007. Development of lactococcal GEM-based pneumococcal vaccines. Vaccine 25:2497–2506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Azizi A, Kumar A, Diaz-Mitoma F, Mestecky J. 2010. Enhancing oral vaccine potency by targeting intestinal M cells. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001147 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bermúdez-Humáran LG, et al. 2004. An inducible surface presentation system improves cellular immunity against human papillomavirus type 16 E7 antigen in mice after nasal administration with recombinant lactococci. J. Med. Microbiol. 53:427–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bermúdez-Humáran LG, et al. 2005. A novel mucosal vaccine based on live lactococci expressing E7 antigen and IL-12 induces systemic and mucosal immune responses and protects mice against human papillomavirus type 16-induced tumors. J. Immunol. 175:7297–7302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bermúdez-Humáran LG, Kharrat P, Chatel JM, Langella P. 2011. Lactococci and lactobacilli as mucosal delivery vectors for therapeutic proteins and DNA vaccines. Microb. Cell Fact. 10(Suppl 1):S4 doi:10.1186/1475-2859-10-S1-S4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bron PA, van Baarlen P, Kleerebezem M. 2012. Emerging molecular insights into the interaction between probiotics and the host intestinal mucosa. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10:66–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bühler OT, et al. 2006. The Yersinia enterocolitica invasin protein promotes major histocompatibility complex class I- and class II-restricted T-cell responses. Infect. Immun. 74:4322–4329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Buist G, Steen A, Kok J, Kuipers OP. 2008. LysM, a widely distributed protein motif for binding to (peptido)glycans. Mol. Microbiol. 68:838–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carlsen H, Moskaug JO, Fromm SH, Blomhoff R. 2002. In vivo imaging of NF-κB activity. J. Immunol. 168:1441–1446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carlsson F, et al. 2006. Signal sequence directs localized secretion of bacterial surface proteins. Nature 442:943–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clark MA, Hirst BH, Jepson MA. 1998. M-cell surface β1 integrin expression and invasin-mediated targeting of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis to mouse Peyer's patch M cells. Infect. Immun. 66:1237–1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cortes-Perez NG, et al. 2005. Cell-surface display of E7 antigen from human papillomavirus type-16 in Lactococcus lactis and in Lactobacillus plantarum using a new cell-wall anchor from lactobacilli. J. Drug Target. 13:89–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Corthésy B, Boris S, Isler P, Grangette C, Mercenier A. 2005. Oral immunization of mice with lactic acid bacteria producing Helicobacter pylori urease B subunit partially protects against challenge with Helicobacter felis. J. Infect. Dis. 192:1441–1449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Critchley-Thorne RJ, Stagg AJ, Vassaux G. 2006. Recombinant Escherichia coli expressing invasin targets the Peyer's patches: the basis for a bacterial formulation for oral vaccination. Mol. Ther. 14:183–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Critchley RJ, et al. 2004. Potential therapeutic applications of recombinant, invasive E. coli. Gene Ther. 11:1224–1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. del Rio B, et al. 2008. Oral immunization with recombinant Lactobacillus plantarum induces a protective immune response in mice with Lyme disease. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 15:1429–1435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dersch P, Isberg RR. 1999. A region of the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis invasin protein enhances integrin-mediated uptake into mammalian cells and promotes self-association. EMBO J. 18:1199–1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Detmer A, Glenting J. 2006. Live bacterial vaccines—a review and identification of potential hazards. Microb. Cell Fact. 5:23 doi:10.1186/1475-2859-5-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Diep DB, Mathiesen G, Eijsink VGH, Nes IF. 2009. Use of lactobacilli and their pheromone-based regulatory mechanism in gene expression and drug delivery. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 10:62–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dieye Y, Usai S, Clier F, Gruss A, Piard JC. 2001. Design of a protein-targeting system for lactic acid bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 183:4157–4166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eitel J, Heise T, Thiesen U, Dersch P. 2005. Cell invasion and IL-8 production pathways initiated by YadA of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis require common signalling molecules (FAK, c-Src, Ras) and distinct cell factors. Cell. Microbiol. 7:63–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Finn RD, et al. 2010. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:D211–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fredriksen L, Mathiesen G, Sioud M, Eijsink VG. 2010. Cell wall anchoring of the 37-kilodalton oncofetal antigen by Lactobacillus plantarum for mucosal cancer vaccine delivery. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:7359–7362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ganster RW, Taylor BS, Shao L, Geller DA. 2001. Complex regulation of human inducible nitric oxide synthase gene transcription by Stat 1 and NF-κB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:8638–8643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grangette C, et al. 2001. Mucosal immune responses and protection against tetanus toxin after intranasal immunization with recombinant Lactobacillus plantarum. Infect. Immun. 69:1547–1553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grassl GA, et al. 2003. Activation of NF-κB and IL-8 by Yersinia enterocolitica invasin protein is conferred by engagement of Rac1 and MAP kinase cascades. Cell. Microbiol. 5:957–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Halbmayr E, et al. 2008. High-level expression of recombinant beta-galactosidases in Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus sakei using a Sakacin P-based expression system. J. Agric. Food Chem. 56:4710–4719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hamburger ZA, Brown MS, Isberg RR, Bjorkman PJ. 1999. Crystal structure of invasin: a bacterial integrin-binding protein. Science 286:291–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heckman KL, Pease LR. 2007. Gene splicing and mutagenesis by PCR-driven overlap extension. Nat. Protoc. 2:924–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hutchings MI, Palmer T, Harrington DJ, Sutcliffe IC. 2009. Lipoprotein biogenesis in Gram-positive bacteria: knowing when to hold 'em, knowing when to fold 'em. Trends Microbiol. 17:13–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Isberg RR, Leong JM. 1990. Multiple β1 chain integrins are receptors for invasin, a protein that promotes bacterial penetration into mammalian cells. Cell 60:861–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jang MH, et al. 2004. Intestinal villous M cells: an antigen entry site in the mucosal epithelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:6110–6115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Josson K, et al. 1989. Characterization of a gram-positive broad-host-range plasmid isolated from Lactobacillus hilgardii. Plasmid 21:9–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kajikawa A, Masuda K, Katoh M, Igimi S. 2010. Adjuvant effects for oral immunization provided by recombinant Lactobacillus casei secreting biologically active murine interleukin-1β. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 17:43–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kajikawa A, et al. 2011. Dissimilar properties of two recombinant Lactobacillus acidophilus strains displaying Salmonella FliC with different anchoring motifs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:6587–6596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kampik D, Schulte R, Autenrieth IB. 2000. Yersinia enterocolitica invasin protein triggers differential production of interleukin-1, interleukin-8, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and tumor necrosis factor alpha in epithelial cells: implications for understanding the early cytokine network in Yersinia infections. Infect. Immun. 68:2484–2492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kim JH, Park IS, Kim BG. 2005. Development and characterization of membrane surface display system using molecular chaperon, prsA, of Bacillus subtilis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 334:1248–1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kleerebezem M, et al. 2003. Complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:1990–1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lavelle EC, O'Hagan DT. 2006. Delivery systems and adjuvants for oral vaccines. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 3:747–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liang Y, Zhou Y, Shen P. 2004. NF-κB and its regulation on the immune system. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 1:343–350 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu JK, et al. 2009. Induction of immune responses in mice after oral immunization with recombinant Lactobacillus casei strains expressing enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli F41 fimbrial protein. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:4491–4497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu X, Lagenaur LA, Lee PP, Xu Q. 2008. Engineering of a human vaginal Lactobacillus strain for surface expression of two-domain CD4 molecules. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:4626–4635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Marra A, Isberg RR. 1997. Invasin-dependent and invasin-independent pathways for translocation of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis across the Peyer's patch intestinal epithelium. Infect. Immun. 65:3412–3421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mathiesen G, et al. 2009. Genome-wide analysis of signal peptide functionality in Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. BMC Genomics 10:425 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-10-425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mathiesen G, Sveen A, Piard JC, Axelsson L, Eijsink VG. 2008. Heterologous protein secretion by Lactobacillus plantarum using homologous signal peptides. J. Appl. Microbiol. 105:215–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Moeini H, Rahim RA, Omar AR, Shafee N, Yusoff K. 2011. Lactobacillus acidophilus as a live vehicle for oral immunization against chicken anemia virus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 90:77–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mohamadzadeh M, Duong T, Hoover T, Klaenhammer TR. 2008. Targeting mucosal dendritic cells with microbial antigens from probiotic lactic acid bacteria. Expert Rev. Vaccines 7:163–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mohamadzadeh M, Duong T, Sandwick SJ, Hoover T, Klaenhammer TR. 2009. Dendritic cell targeting of Bacillus anthracis protective antigen expressed by Lactobacillus acidophilus protects mice from lethal challenge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:4331–4336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mosser DM, Edwards JP. 2008. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8:958–969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Natale P, Bruser T, Driessen AJ. 2008. Sec- and Tat-mediated protein secretion across the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane-distinct translocases and mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1778:1735–1756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Norton PM, et al. 1996. Factors affecting the immunogenicity of tetanus toxin fragment C expressed in Lactococcus lactis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 14:167–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. 2011. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat. Methods 8:785–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pfeiler EA, Klaenhammer TR. 2007. The genomics of lactic acid bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 15:546–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schulte R, et al. 2000. Yersinia enterocolitica invasin protein triggers IL-8 production in epithelial cells via activation of Rel p65-p65 homodimers. FASEB J. 14:1471–1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Serbina NV, Jia T, Hohl TM, Pamer EG. 2008. Monocyte-mediated defense against microbial pathogens. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 26:421–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sica A, Bronte V. 2007. Altered macrophage differentiation and immune dysfunction in tumor development. J. Clin. Invest. 117:1155–1166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sørvig E, et al. 2003. Construction of vectors for inducible gene expression in Lactobacillus sakei and L plantarum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 229:119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sørvig E, Mathiesen G, Naterstad K, Eijsink VG, Axelsson L. 2005. High-level, inducible gene expression in Lactobacillus sakei and Lactobacillus plantarum using versatile expression vectors. Microbiology 151:2439–2449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Steidler L, et al. 1998. Mucosal delivery of murine interleukin-2 (IL-2) and IL-6 by recombinant strains of Lactococcus lactis coexpressing antigen and cytokine. Infect. Immun. 66:3183–3189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Uliczka F, Kornprobst T, Eitel J, Schneider D, Dersch P. 2009. Cell invasion of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis by invasin and YadA requires protein kinase C, phospholipase C-γ1 and Akt kinase. Cell. Microbiol. 11:1782–1801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wells J. 2011. Mucosal vaccination and therapy with genetically modified lactic acid bacteria. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2:423–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wells JM. 2011. Immunomodulatory mechanisms of lactobacilli. Microb. Cell Fact. 10(Suppl 1):S17 doi:10.1186/1475-2859-10-S1-S17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wells JM, Mercenier A. 2008. Mucosal delivery of therapeutic and prophylactic molecules using lactic acid bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:349–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zhou M, Theunissen D, Wels M, Siezen RJ. 2010. LAB-Secretome: a genome-scale comparative analysis of the predicted extracellular and surface-associated proteins of Lactic Acid Bacteria. BMC Genomics 11:651 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]