Abstract

The bacteriocin enterocin A (EntA) produced by Enterococcus faecium T136 has been successfully cloned and produced by the yeasts Pichia pastoris X-33EA, Kluyveromyces lactis GG799EA, Hansenula polymorpha KL8-1EA, and Arxula adeninivorans G1212EA. Moreover, P. pastoris X-33EA and K. lactis GG799EA produced EntA in larger amounts and with higher antimicrobial and specific antimicrobial activities than the EntA produced by E. faecium T136.

TEXT

The enterococci are lactic acid bacteria (LAB) that produce ribosomally synthesized antimicrobial peptides or proteins known as enterocins that attract considerable interest for their potential use as natural and nontoxic food preservatives, for human and veterinary applications, and in the animal production field (17, 26, 34). However, since enterocins may be produced by enterococcal species carrying antibiotic resistance genes and/or genes that code for potential virulence factors, for hygienic, safety, and biotechnological reasons, the production of enterocins in other microbial hosts is being evaluated (9, 20, 21, 22). The enterocin A (EntA) produced by Enterococcus faecium T136 (11) is a class IIa bacteriocin with high antilisterial activity (14, 16). The presence of Listeria monocytogenes in food can be reduced by in situ EntA production (23, 29), by the addition of semipurified or purified preparations of EntA (1, 24), or by the incorporation of EntA into biodegradable packaging films (31). The heterologous production of EntA by bacterial hosts has been attained through the expression of its native biosynthetic genes (29), by exchange or replacement of the EntA leader peptide and/or dedicated processing and secretion systems (33), or by fusion of mature EntA to signal peptides that act as secretion signals (10, 28, 32). Recently, several yeast platforms have been developed for the large-scale expression of proteins (5, 7, 13, 19). However, the heterologous production of bacteriocins by yeasts has not yet been fully exploited.

Microbial strains, plasmids, and cloning of mature EntA.

The microbial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The primers and inserts used for the construction of the recombinant plasmids are listed in Table 2. For production of EntA by Pichia pastoris X-33 and Kluyveromyces lactis GG799, derivatives of plasmids pPICZαA and pKLAC2 were obtained. Primers PKEA-F and PKEA-R were used for PCR amplification from the total genomic DNA of E. faecium T136 of a 178-bp XhoI-NotI fragment (KR-EA) carrying the α-factor Kex2 signal protease cleavage site without the Glu-Ala spacer, fused to mature EntA (entA without its leader sequence). The resulting XhoI-NotI cleavage fragment was ligated into the pPICZαA and pKLAC2 vectors to generate plasmids pPICEA and pKLEA, respectively. The presence of the linearized pPICEA and pKLEA plasmids in the transformed P. pastoris X-33EA and K. lactis GG799EA isolates was confirmed by a bacteriocinogenicity test, PCR, and sequencing of the inserts. The recombinant plasmids pBTEA and pBYEA were also constructed for the cloning of mature entA into Hansenula polymorpha KL8-1 and Arxula adeninivorans G1212. The primers AHEA-F and AHEA-R were used for PCR amplification from plasmid pPICEA of a 421-bp EcoRI-NotI fragment (MF-KR-EA) carrying the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mating pheromone α-factor 1 secretion signal (MFα1s) with the Kex2 signal protease cleavage site without the Glu-Ala spacer, fused to mature EntA. The resulting EcoRI-NotI cleavage fragment was ligated into plasmids pBS-TEF1-PHO5 and pBS-AYNI1P-PHO5 to generate intermediate plasmids pBS-TEF1-MF-KR-EA-PHO5 and pBS-AYNI1P-MF-KR-EA-PHO5, respectively. Purified pBS-TEF1-MF-KR-EA-PHO5 was digested with SpeI-SacII, and the resulting 894-bp SpeI-SacII cleavage fragment (TEF1-MF-KR-EA-PHO5) was ligated into plasmid pB25S-ALEU2m to generate plasmid pBTEA. Plasmid pBTEA was further restricted with AscI to remove the Escherichia coli part of the plasmid construct, and the yeast ribosomal DNA integrative cassette (YRC) with the selection marker and expression module, flanked by rRNA gene sequences, was used to transform H. polymorpha KL8-1 competent cells (7). Purified pBS-AYNI1P-MF-KR-EA-PHO5 was digested with SpeI-SacII, and the resulting 1,187-bp SpeI-SacII cleavage fragment (AYNI1P-MF-KR-EA-PHO5) was ligated into plasmid pB25S-ATRP1m to generate the final plasmid pBYEA. Plasmid pBYEA was further restricted with NcoI, and the resulting YRC was used to transform A. adeninivorans G1212 competent cells (7, 8). The presence of the YRCs integrated into H. polymorpha KL8-1EA and A. adeninivorans G1212EA, respectively, was confirmed by a bacteriocinogenicity test, PCR, and sequencing of the inserts.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Source and/or referenceb |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Enterococcus faecium | ||

| T136 | EntA and EntB producer; control strain | DNBTA; 11 |

| P13 | EntP producer; MPA and ADT indicator | DNBTA; 12 |

| Escherichia coli JM109 | Selection of recombinant plasmids | Promega |

| Pichia pastoris X-33 | Yeast wild type | Invitrogen |

| Kluyveromyces lactis GG799 | Yeast wild type | New England Biolabs |

| Hansenula polymorpha KL8-1 | Yeast auxotrophic mutant (aleu2 ura3−) | IPK; 25 |

| Arxula adeninivorans G1212 | Yeast auxotrophic mutant (atrp1−) | IPK; 39 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pPICZαA | Zeor; integrative plasmid carrying the secretion signal sequence from the S. cerevisiae α-factor prepropetide and functional sites for integration at the 5′ AOX1 locus of P. pastoris X-33 | Invitrogen Life Technologies |

| pPICEA | pPICZαA derivative carrying the PCR product KR-EA | This work |

| pKLAC2 | Ampr; integrative plasmid carrying the Aspergillus nidulans acetamidase gene (amdS), the secretion signal sequence from the S. cerevisiae α-factor prepropeptide, and functional sites for integration at the lac-4 locus of K. lactis GG799 | New England Biolabs |

| pKLEA | pKLAC2 derivative carrying the PCR product KR-EA | This work |

| pBS-TEF1-PHO5 | Ampr; integrative plasmid carrying the constitutive A. adeninivorans-derived PTEF1 promoter and the S. cerevisiae-derived PHO5 terminator | IPK |

| pBS-TEF1-MF-KR-EA-PHO5 | pBS-TEF1-PHO5 derivative carrying the PCR product MF-KR-EA | This work |

| pB25S-ALEU2 m | Kanr; integrative plasmid carrying the A. adeninivorans-derived 25S rRNA gene fragment and the ALEU2m gene for auxotrophic complementation | IPK |

| pBTEA | pB25S-ALEU2m derivative carrying the fragment TEF1-MF-KR-EA-PHO5 | This work |

| pBS-AYNI1-PHO5 | Ampr; integrative plasmid carrying the inducible A. adeninivorans-derived PAYNI1 promoter and the S. cerevisiae-derived PHO5 terminator | IPK |

| pBS-AYNI1-MF-KR-EA-PHO5 | pBS-AYNI1-PHO5 derivative carrying the PCR product MF-KR-EA | This work |

| pB25S-ATRP1 m | Kanr; integrative plasmid carrying the A. adeninivorans-derived 25S rRNA gene fragment and the ATRP1m gene for auxotrophic complementation | IPK |

| pBYEA | pB25S-ATRP1m derivative carrying the fragment AYNI1-MF-KR-EA-PHO5 | This work |

ADT, agar well diffusion test; Zeor, zeocin resistance.

DNBTA, Departamento de Nutrición, Bromatología y Tecnología de los Alimentos, Facultad de Veterinaria, Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Madrid, Spain); IPK, Leibniz-Institut für Pflanzengenetik und Kulturpflanzenforschung (Gatersleben, Germany).

Table 2.

Primers, PCR products, and fragments used in this study

| Primer, PCR product, or fragment | Nucleotide sequence (5′–3′) or descriptiona | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Primers | ||

| PKEA-F | GAATTCTCGAGAAAAGAACCACTCATAGTGGAAAATATTATGGAAATGG | Amplification of KR-EA |

| PKEA-R | ATAAGTTGCGGCCGCTATTTAGCACTTCCCTGGAATTGCTCC | Amplification of KR-EA |

| AHEA-F | AAAGAATTCATGAGATTTCCTTCAATTTTTACT | Amplification of MF-KR-EA |

| AHEA-R | TATGCGGCCGCTATTTAGCACTTCCCT | Amplification of MF-KR-EA |

| PCR products | ||

| KR-EA | 178-bp XhoI/NotI fragment containing the α-factor Kex2 signal protease cleavage site fused to mature EntA | Cloning in pPICZαA and pKLAC2 |

| MF-KR-EA | 421-bp EcoRI/NotI fragment containing the α-mating factor domain fused to the α-factor Kex2 signal protease cleavage site and mature EntA | Cloning in pBS-TEF1-PHO5 and pBS-AYNI1-PHO5 |

| Fragments | ||

| TEF1-MF-KR-EA-PHO5 | 894-bp SpeI/SacII fragment containing the constitutive A. adeninivorans-derived TEF1 promoter fused to the α-factor Kex2 signal protease cleavage site, mature EntA, and the S. cerevisiae-derived PHO5 terminator | Cloning in pB25S-ALEU2m |

| AYNI1-MF-KR-EA-PHO5 | 1,187-bp SpeI/SacII fragment containing the constitutive A. adeninivorans-derived PAYNI1 promoter fused to the α-factor Kex2 signal protease cleavage site, mature EntA, and the S. cerevisiae-derived PHO5 terminator | Cloning in pB25S-ATRP1m |

Cleavage sites for restriction enzymes are underlined in the primers. The Kex2 protease processing site is shown in bold.

Antimicrobial activity, ELISA, purification of EntA, and mass spectrometry analyses.

The direct antimicrobial activity of the transformed yeasts was screened by a streak-on-agar test (SOAT) (21), and the antimicrobial activity of their supernatants was examined by a microtiter plate assay (MPA) (22). One bacteriocin unit (BU) was defined as the reciprocal of the highest dilution of the bacteriocin causing 50% growth inhibition (50% of the turbidity of the control culture without bacteriocin) (22). Specific polyclonal anti-EntA antibodies and a noncompetitive indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (NCI-ELISA) were used to detect and quantify the amounts of EntA in the supernatants of the producer yeasts (10). The EntA was purified to homogeneity as previously described (10), and the purified fractions were subjected to matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (10). The antimicrobial activity of supernatants and their purified EntA were evaluated against L. monocytogenes strains from the CECT (Colección Española de Cultivos Tipo, Valencia, Spain) by an MPA.

Heterologous production of EntA by recombinant yeasts.

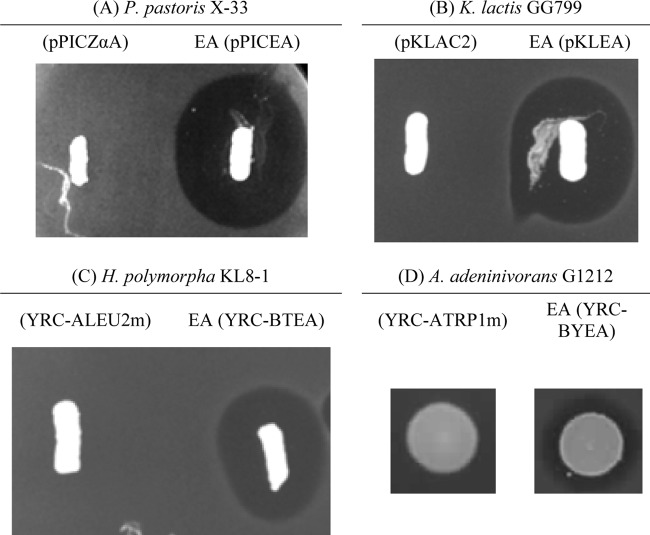

The P. pastoris X-33EA, K. lactis GG799EA, H. polymorpha KL8-1EA, and A. adeninivorans G1212EA isolates were selected for their high antimicrobial activity against E. faecium P13 (Fig. 1). Yeasts containing control plasmids were used as bacteriocin-negative hosts to disprove that the antagonistic activity of the recombinant producers was due to metabolites other than bacteriocins. The highest production of EntA by P. pastoris X-33EA, K. lactis GG799EA, and H. polymorpha KL8-1EA was 30-, 7-, and 3.2-fold higher, respectively, than the production of EntA by E. faecium T136 (Table 3). The PAOX1 and PLAC4 promoters used in this study are strong inducible promoters to drive the synthesis of heterologous proteins in P. pastoris and K. lactis, respectively (40, 43). The higher production of EntA by P. pastoris X-33EA than by K. lactis GG799EA may be due to promoter differences, to the dosages of the entA gene in their genomes, and/or to differences in the genetic backgrounds of the two strains. On the other hand, the PTEF1 promoter that drives the production of EntA in H. polymorpha KL8-1EA is a strong but constitutive promoter (42). For protein production, inducible systems are often considered superior to constitutive expression systems, since the former enable the achievement of sufficient biomass prior to the initiation of target protein expression and the consequent metabolic burden on the cell (27). The decrease in EntA in the supernatants of P. pastoris X-33EA, K. lactis GG799EA, and H. polymorpha KL8-1EA may be ascribed to, among other factors, the attachment of EntA to cell walls, the formation of aggregates, and/or proteinase degradation, and it may be the subject of further investigations. However, no EntA production by A. adeninivorans G1212EA was detectable (Table 3). The nitrite reductase promoter (PAYNI1) used for the expression of entA in A. adeninivorans G1212EA is highly repressed by compounds with reduced nitrogen (6), and maybe other factors, such as a lower entA gene dosage or deficient MFα1s-entA recognition by the A. adeninivorans G1212EA Sec machinery, would explain the low antimicrobial activity and undetectable production of secreted EntA.

Fig 1.

Antimicrobial activities of recombinant yeasts as determined by a SOAT. Panels: A, P. pastoris X-33 (pPICZαA) and X-33EA (pPICEA); B, K. lactis GG799 (pKLAC2) and GG799EA (pKLEA); C, H. polymorpha KL8-1 (YRC-ALEU2m) and KL8-1EA (YRC-BTEA); D, A. adeninivorans G1212 (YRC-ATRP1m) and G1212EA (YRC-BYEA). The P. pastoris X-33 derivatives were streaked onto the surfaces of plates containing 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6), 1.34% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 4 × 10−5% biotin, and 0.5% methanol; the K. lactis GG799 derivatives were streaked onto plates containing 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% galactose; the H. polymorpha KL8-1 derivatives were streaked onto yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (Sigma-Aldrich Inc.) plates; and the A. adeninivorans G1212 derivatives were spotted onto YMM-glucose plates containing 20 mM NaNO3 (YMM-NO3) (6). All plates were incubated at 30°C. After growth of the yeast hosts, 40 ml of MRS (Oxoid Ltd.) soft agar containing the indicator microorganism E. faecium P13 at about 1 × 105 CFU/ml was poured over the plates, which were then incubated at 30°C overnight for development of halos of inhibition.

Table 3.

Production and antimicrobial activities of EntA from supernatants of P. pastoris X-33EA, K. lactis GG799EA, H. polymorpha KL8-1EA, and A. adeninivorans G1212EA

| Strain and incubation time (h) | OD600a | EntA production (μg/ml)b | Antimicrobial activity (BU/ml)c | Specific antimicrobial activity (BU/μg EntA)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. pastoris X-33EA | ||||

| 0 | 0.9 | ND | NA | NE |

| 2 | 1.6 | 0.5 | NA | NE |

| 4 | 2.8 | 1.1 | 31 | 28 |

| 6 | 3.1 | 8.4 | 195 | 23 |

| 8 | 3.9 | 14.6 | 597 | 41 |

| 10 | 4.4 | 17.1 | 1,562 | 91 |

| 12 | 5.3 | 22.9 | 14,910 | 651 |

| 24 | 6.5 | 33.0 | 147,324 | 4,464 |

| 36 | 6.5 | 45.1 | 249,325 | 5,528 |

| 48 | 6.8 | 38.6 | 17,514 | 454 |

| 60 | 6.9 | 37.6 | 14,276 | 380 |

| 72 | 7.0 | 21.2 | 3,156 | 149 |

| K. lactis GG799EA | ||||

| 0 | 1,0 | ND | NA | NE |

| 2 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1,101 | 551 |

| 4 | 3.4 | 6.0 | 6,678 | 1,113 |

| 6 | 7.6 | 10.5 | 34,148 | 3,252 |

| 8 | 8.4 | 10.0 | 29,034 | 2,903 |

| 10 | 10.2 | 9.5 | 22,817 | 2,402 |

| 24 | 14.6 | 8.7 | 9,278 | 1,066 |

| 36 | 16.6 | 7.8 | 7,951 | 1,019 |

| 48 | 16.0 | 7.2 | 6,004 | 834 |

| 60 | 16.2 | 6.0 | 3,083 | 514 |

| H. polymorpha KL8-1EA | ||||

| 0 | 1.0 | ND | NA | NE |

| 2 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 75 | 68 |

| 4 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 248 | 124 |

| 6 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 489 | 213 |

| 8 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 207 | 86 |

| 10 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 124 | 50 |

| 12 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 77 | 35 |

| 24 | 7.2 | 4.8 | 26 | 5 |

| 36 | 7.7 | 4.1 | 23 | 6 |

| 48 | 8.5 | 3.8 | NA | NE |

| 60 | 8.8 | 3.6 | NA | NE |

| 72 | 8.4 | 3.2 | NA | NE |

| A. adeninivorans G1212EA | ||||

| 0 | 0.1 | ND | NA | NE |

| 12 | 0.8 | ND | NA | NE |

| 24 | 7.0 | ND | 32 | NE |

| 36 | 24.8 | ND | 112 | NE |

| 48 | 33.6 | ND | 86 | NE |

| 60 | 34.6 | ND | 80 | NE |

| 72 | 46.8 | ND | 79 | NE |

| 84 | 42.4 | ND | 82 | NE |

| 96 | 34.6 | ND | 75 | NE |

| 108 | 38.6 | ND | 76 | NE |

| E. faecium T136 (16 h) | 0.9 | 1.5 | 577 | 385 |

OD600, optical density of the culture at 600 nm.

Production of EntA was calculated by using an NCI-ELISA with polyclonal antibodies specific for EntA. ND, not detected.

Calculated against E. faecium P13 (EntAs). NA, no activity.

Calculated as the antimicrobial activity against E. faecium P13 divided by the amount of EntA produced. NE, not evaluable. P. pastoris X-33EA was grown in broth containing 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6), 1.34% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 4 × 10−5% biotin, and 0.5% methanol; K. lactis GG799EA was grown in broth containing 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% galactose; H. polymorpha KL8-1EA was grown in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose broth; A. adeninivorans G1212EA was grown in YMM-NO3 broth (6); and E. faecium T136 was grown in MRS broth.

Most of the data are means from two independent determinations in triplicate.

The antimicrobial activity of the supernatants of P. pastoris X-33EA was 432-fold higher and that of K. lactis GG799EA was 59-fold higher than that of E. faecium T136, and those of H. polymorpha KL8-1EA and A. adeninivorans G1212EA represented, respectively, 85% and 19% of the antimicrobial activity of E. faecium T136. Furthermore, the specific antimicrobial activity of P. pastoris X-33EA and K. lactis GG799EA was 14.4- and 8.4-fold higher, respectively, than that of E. faecium T136 (Table 3). Bacteriocins cloned into recombinant S. cerevisiae (2, 37, 41) and P. pastoris (3, 4, 21, 36) hosts have been produced with variable success regarding its secretion and functional expression. Recombinant LAB, heterologous producers of EntA, also show higher EntA production (1.5- to 18.5-fold) than E. faecium T136, and the EntA they produce shows higher antimicrobial activity (1.5- to 6.6-fold) than that of the EntA produced by E. faecium T136, although the specific antimicrobial activity of the EntA produced was lower than that deduced from its production (10, 32). Recombinant LAB, heterologous producers of enterocin P (EntP) and hiracin JM79, also showed higher production and antimicrobial activity of both bacteriocins, whereas their specific antimicrobial activity differed from that of the enterocins produced by the natural enterococcal producers (9, 22, 36). It has been speculated that the lower specific antimicrobial activity of heterologous bacteriocins produced by LAB may be due to, among many other factors, deficiencies in disulfide bond (DSB) formation, a conserved mechanism for stabilizing extracytoplasmic proteins carried out by thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases (9, 10). EntA has two DSBs that seems to improve its antimicrobial activity (15), whereas DSB formation is a prime reason why proteins containing DSBs are difficult to produce in biologically active form by bacterial cell factories (18). An advantage of yeasts over bacterial expression systems is that yeasts may perform posttranslational modifications such as processing of signal sequences, DSB formation, and protein folding in a more efficient way (38, 44). Possibly, the stability of the EntA produced by P. pastoris X-33EA and K. lactis GG799EA may also be enhanced by the amino acid-rich supplements in the growth medium which may act as alternative and competing substrates for proteinases (30, 35).

Purification of the EntA secreted by P. pastoris X-33EA, K. lactis GG799EA, and H. polymorpha KL8-1EA permitted elevated recovery and high specific antimicrobial activity of the purified bacteriocin. Moreover, the purified EntAs from the recombinant yeasts (Fig. 2) and E. faecium T136 (10) showed major peaks with similar molecular masses, suggesting that no different posttranslational modifications occurred. The supernatants of P. pastoris X-33EA and K. lactis GG799EA and their secreted EntA, purified to homogeneity, showed higher antimicrobial activity against L. monocytogenes than that of E. faecium T136 (results not shown). Accordingly, P. pastoris X-33EA and K. lactis GG799EA would be considered unique yeast cell factories and an alternative to LAB for the heterologous production and recovery of biologically active EntA.

Fig 2.

Mass spectrometry analysis of purified EntA from P. pastoris X-33EA (A), K. lactis GG799EA (B), and H. polymorpha KL8-1EA (C).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by grant AGL2006-01042 from the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (MEC), grant AGL2009-08348 from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (MICINN), and grant S2009/AGR-1489 from the Comunidad de Madrid (CAM). J. Borrero holds a research contract from the CAM, J. J. Jiménez is the recipient of a fellowship (FPI) from the MICINN, and L. Gútiez holds a fellowship (FPU) from the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (MEC), Spain.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 8 June 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Aymerich MT, et al. 2000. Application of enterocins as biopreservatives against Listeria innocua in meat products. J. Food Prot. 63:721–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Basanta A, et al. 2009. Development of bacteriocinogenic strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae heterologously expressing and secreting the leaderless enterocin L50 peptides L50A and L50B from Enterococcus faecium L50. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:2382–2392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Basanta A, et al. 2010. Use of the yeast Pichia pastoris as an expression host for secretion of enterocin L50, a leaderless two-peptide (L50A and L50B) bacteriocin from Enterococcus faecium L50. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:3314–3324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beaulieu L, et al. 2005. Production of pediocin PA-1 in the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris reveals unexpected inhibition of its biological activity due to the presence of collagen-like material. Protein Expr. Purif. 43:111–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Böer E, Steinborn G, Kunze G, Gellissen G. 2007. Yeast expression platforms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 77:513–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Böer E, Bode R, Mock HP, Piontek M, Kunze G. 2009. Atan1p-an extracellular tannase from the dimorphic yeast Arxula adeninivorans: molecular cloning of the ATAN1 gene and characterization of the recombinant enzyme. Yeast 26:323–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Böer E, Piontek M, Kunze G. 2009. Xplor 2—a new transformation/expression system for recombinant protein production in the yeast Arxula adeninivorans. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 84:583–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Böer E, Schröter A, Bode R, Piontek M, Kunze G. 2009. Characterization and expression analysis of a gene cluster for nitrate assimilation from the yeast Arxula adeninivorans. Yeast 26:83–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Borrero J, et al. 2011. Use of the usp45 lactococcal secretion signal sequence to drive the secretion and functional expression of enterococcal bacteriocins in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 89:131–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Borrero J, et al. 2011. Protein expression vector and secretion signal peptide optimization to drive the production, secretion, and functional expression of the bacteriocin enterocin A (EntA) in lactic acid bacteria. J. Biotechnol. 156:76–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Casaus P, et al. 1997. Enterocin B, a new bacteriocin from Enterococcus faecium T136 which can act synergistically with enterocin A. Microbiology 143:2287–2294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cintas LM, Casaus P, Håvarstein LS, Hernández PE, Nes IF. 1997. Biochemical and genetic characterization of enterocin P, a novel sec-dependent bacteriocin from Enterococcus faecium P13 with a broad antimicrobial spectrum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4321–4330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Daly R, Hearn MTW. 2005. Expression of heterologous proteins in Pichia pastoris: a useful experimental tool in protein engineering and production. J. Mol. Recognit. 18:119–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Drider D, Fimland G, Héchard Y, McMullen LM, Prévost H. 2006. The continuing story of class IIa bacteriocins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70:564–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eijsink VGH, Skeie M, Middelhoven PH, Brurberg MB, Nes IF. 1998. Comparative studies of class II bacteriocins of lactic acid bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3275–3281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ennahar S, Deschamps N. 2000. Anti-Listeria effect of enterocin A, produced by cheese-isolated Enterococcus faecium EFM01, relative to other bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 88:449–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Franz CM, van Belkum MJ, Holzapfel WH, Abriouel H, Gálvez A. 2007. Diversity of enterococcal bacteriocins and their grouping in a new classification scheme. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 31:293–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Freitas DA, et al. 2005. Secretion of Streptomyces tendae antifungal protein 1 by Lactococcus lactis. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 38:1585–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gellissen G, et al. 2005. New yeast expression platforms based on methylotrophic Hansenula polymorpha and Pichia pastoris and on dimorphic Arxula adeninivorans and Yarrowia lipolytica. A comparison. FEMS Yeast Res. 5:1079–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gutiérrez J, et al. 2005. Cloning, production and functional expression of enterocin P, a Sec-dependent bacteriocin produced by Enterococcus faecium P13, in Escherichia coli. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 103:239–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gutiérrez J, et al. 2005. Production of enterocin P, an antilisterial pediocin-like bacteriocin from Enterococcus faecium P13, in Pichia pastoris. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3004–3008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gutiérrez J, Larsen R, Cintas LM, Kok J, Hernández PE. 2006. High-level heterologous production and functional expression of the Sec-dependent enterocin P from Enterococcus faecium P13, in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 72:41–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Izquierdo E, Marchioni E, Aoude-Werner D, Hasselmann C, Ennahar S. 2009. Smearing of soft cheese with Enterococcus faecium WHE 81, a multi-bacteriocin producer, against Listeria monocytogenes. Food Microbiol. 26:16–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jofré A, Aymerich T, Garriga M. 2009. Improvement of the food safety of low acid fermented sausages by enterocins A and B and high pressure. Food Control 20:179–184 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kang HA, Gellisen G. 2005. Hansenula polymorpha, p 111–142 In Gellissen G. (ed), Production of recombinant proteins. Novel microbial and eukaryotic expression systems. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 26. Khan H, Flint S, Yu PL. 2010. Enterocins in food preservation. Int. J. Food. Microbiol. 141:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kim JH, Mills DA. 2007. Improvement of a nisin-inducible expression vector for use in lactic acid bacteria. Plasmid 58:275–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Klocke M, Mundt K, Idler F, Jung S, Bachausen JE. 2005. Heterologous expression of enterocin A, a bacteriocin from Enterococcus faecium, fused to a cellulose-binding domain in Escherichia coli results in a functional protein with inhibitory activity against Listeria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 67:532–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu L, O′Conner P, Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. 2008. Controlling Listeria monocytogenes in cottage cheese through heterologous production of enterocin A by Lactococcus lactis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 104:1059–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Macauley-Patrick S, Fazenda ML, McNeil B, Harvey LM. 2005. Heterologous protein production using the Pichia pastoris expression system. Yeast 22:249–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marcos B, Aymerich T, Monfort JM, Garriga M. 2008. High-pressure processing and antimicrobial biodegradable packaging to control Listeria monocytogenes during storage of cooked ham. Food Microbiol. 25:177–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Martín M, et al. 2007. Cloning, production and expression of the bacteriocin enterocin A produced by Enterococcus faecium PLBC21 in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 76:667–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Martínez JM, Kok J, Sanders JW, Hernández PE. 2000. Heterologous coproduction of enterocin A and pediocin PA-1 by Lactococcus lactis: detection by specific peptide-directed antibodies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3543–3549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Montalbán-López M, Sánchez-Hidalgo M, Valdivia E, Martínez-Bueno M, Maqueda M. 2011. Are bacteriocins underexploited? Novel applications for old antimicrobials. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 12:1205–1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nøhr J, Kristiansen K, Krogsdam AM. 2003. Protein expression in yeasts. Methods Mol. Biol. 232:111–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sánchez J, et al. 2008. Cloning and heterologous production of hiracin JM79, a Sec-dependent bacteriocin produced by Enterococcus hirae DCH5, in lactic acid bacteria and Pichia pastoris. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:2471–2479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schoeman H, Vivier MA, du Toit M, Dicks LMT, Pretorius IS. 1999. The development of bactericidal yeast strains by expressing the Pediococcus acidilactici pediocin gene (pedA) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 15:647–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sørensen HP. 2010. Towards universal systems for recombinant gene expression. Microb. Cell Fact. 9:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Steinborn G, Wartmann T, Gellissen G, Kunze G. 2007. Construction of an Arxula adeninivorans host-vector system based on trp1 complementation. J. Biotechnol. 127:392–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Swinkels BW, van Ooyen AJJ, Bonekamp FJ. 1993. The yeast Kluyveromyces lactis as an efficient host for heterologous gene expression. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 64:187–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Van Reenen CA, Chikindas ML, van Zyl WH, Dicks LMT. 2003. Characterization and heterologous expression of a class IIa bacteriocin, plantaricin 423 from Lactobacillus plantarum 423, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 81:29–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wartmann T, et al. 2002. High-level production and secretion of recombinant proteins by the dimorphic yeast Arxula adeninivorans. FEMS Yeast Res. 2:363–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Waterham HR, Digan ME, Koutz PJ, Lair SV, Cregg JM. 1997. Isolation of the Pichia pastoris glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene and regulation and use of its promoter. Gene 186:37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zerbs S, Frank AM, Collart FR. 2009. Bacterial systems for production of heterologous proteins. Methods Enzymol. 463:149–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]