Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the significance of intravesical prostatic protrusion (IPP) for predicting postoperative outcomes in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Materials and Methods

A total of 177 patients with a possible follow-up of at least 6 months who were treated with transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) were analyzed. We divided the patients into two groups on the basis of the degree of IPP: the significant IPP group (IPP≥5 mm, n=74) and the no significant IPP group (IPP<5 mm, n=103). We analyzed postoperative changes in parameters, such as the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), IPSS quality-of-life (QoL) score, maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax), and postvoid residual urine (PVR). The IPSS was subdivided into voiding (IPSS-v) and storage (IPSS-s) symptoms. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify whether IPP could predict surgical outcomes of TURP.

Results

Preoperative parameters were not significantly different between the two groups except for total prostate volume and transitional zone volume. Postoperative changes in IPSS, IPSS-v, IPSS-s, and QoL score were higher in the significant IPP group than in the group with no significant IPP. Changes in Qmax and PVR were not significantly different between the two groups. Multivariate logistic regression analysis (after adjustment for age, prostate-specific antigen level, total prostate volume, and transitional zone volume) revealed that the odds ratios (95% confidence interval) of decreased IPSS and IPSS-s in the significant IPP group were 3.43 (1.03 to 11.44) and 3.51 (1.43 to 8.63), respectively (p=0.045 and 0.006, respectively).

Conclusions

Significant IPP is an independent factor for predicting better postoperative outcomes of IPSS and IPSS-s.

Keywords: Intravesical prostatic protrusion, Prostatic hyperplasia, Transurethral resection of prostate, Treatment outcome

INTRODUCTION

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) can cause bothersome lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). The treatment of BPH includes watchful waiting, medical therapy, conventional surgical therapy, and minimally invasive therapy. Recently, photoselective vaporization of the prostate with a potassium titanyl phosphate laser and Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate have become established as surgical treatment options for LUTS secondary to BPH. However, transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) is still considered the standard surgical therapy for BPH [1-3].

There is no doubt that accurate prediction of surgical outcomes is important when making plans for surgical therapy. Previous studies reported that preoperative parameters for predicting surgical outcomes in men with BPH are age, symptoms, prostate size, transition zone index, and urodynamic abnormalities such as bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) and detrusor overactivity [4-8]. Unfortunately, however, none of these symptoms can predict surgical outcomes exactly; therefore, the need for novel parameters has resurfaced.

Intravesical prostatic protrusion (IPP) is known as a useful non-invasive method for estimating the outcome of a trial without catheter (TWOC) in men with acute urinary retention (AUR) [9,10], for predicting clinical progression of benign prostatic enlargement in patients receiving medical treatment, and [11], especially, for evaluating BOO [12-14]. Thus, we evaluated the significance of IPP for predicting postoperative outcomes in patients with BPH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We reviewed the medical records of 249 patients who underwent TURP, conducted by 3 surgeons, at 3 centers between January 2008 and December 2009. Before initiating this study, we obtained an approval from the institutional review board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital. Indications for TURP were AUR, maximum flow rate (Qmax) less than 15 ml/s, postvoid residual urine (PVR) exceeding 100 ml, bladder stones, and upper urinary tract complications from chronic BOO. In all patients with an increased serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level ≥4 ng/ml, prostate biopsy was undertaken to exclude prostate cancer. Patients with a history of prostate cancer, urethral stricture, neurogenic bladder, and previous prostate or urethral surgery were excluded.

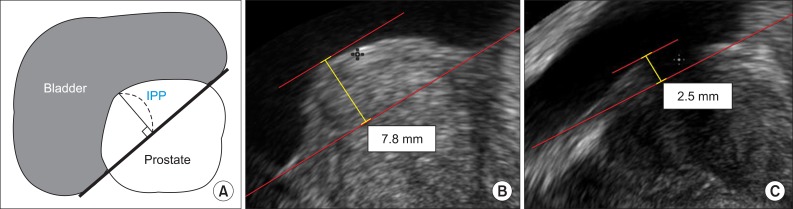

IPP was measured by the vertical distance from the tip of the protruding prostate to the base of the urinary bladder in the sagittal plane of transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Measurement of intravesical prostatic protrusion (IPP). (A) Schematic estimation of IPP: the vertical distance from the tip of the protrusion to the base of the bladder (sagittal views of bladder and prostate by TRUS). (B) IPP of 5 mm or more. (C) IPP of less than 5 mm.

We divided the patients into two groups on the basis of IPP dichotomized at a median of 5 mm: the significant IPP group (IPP≥5 mm, n=74) and the no significant IPP group (IPP<5 mm, n=103). We collected preoperative data for each group including the patient's age, PSA level, International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), IPSS quality-of-life (QoL) score, total prostate volume (TPV), transitional zone volume (TZV), Qmax, and PVR. IPSS was subdivided into voiding (IPSS-v) and storage (IPSS-s) symptoms. TPV and TZV were calculated by use of the following formula: π/6 × transverse diameter × anteroposterior diameter × longitudinal diameter measured by TRUS. We assessed postoperative changes in parameters such as IPSS, IPSS-v, IPSS-s, QoL score, Qmax, and PVR at 6 months after the operation.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS ver. 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and statistical significance was defined as a p-value of <0.05. Student's t-test was carried out to assess the preoperative characteristics and the postoperative changes in clinical outcomes. The odds ratios for improving surgical outcomes in the significant IPP group were calculated by univariate and multivariate logistic regression models after adjustment for age, PSA, TPV, and TZV.

RESULTS

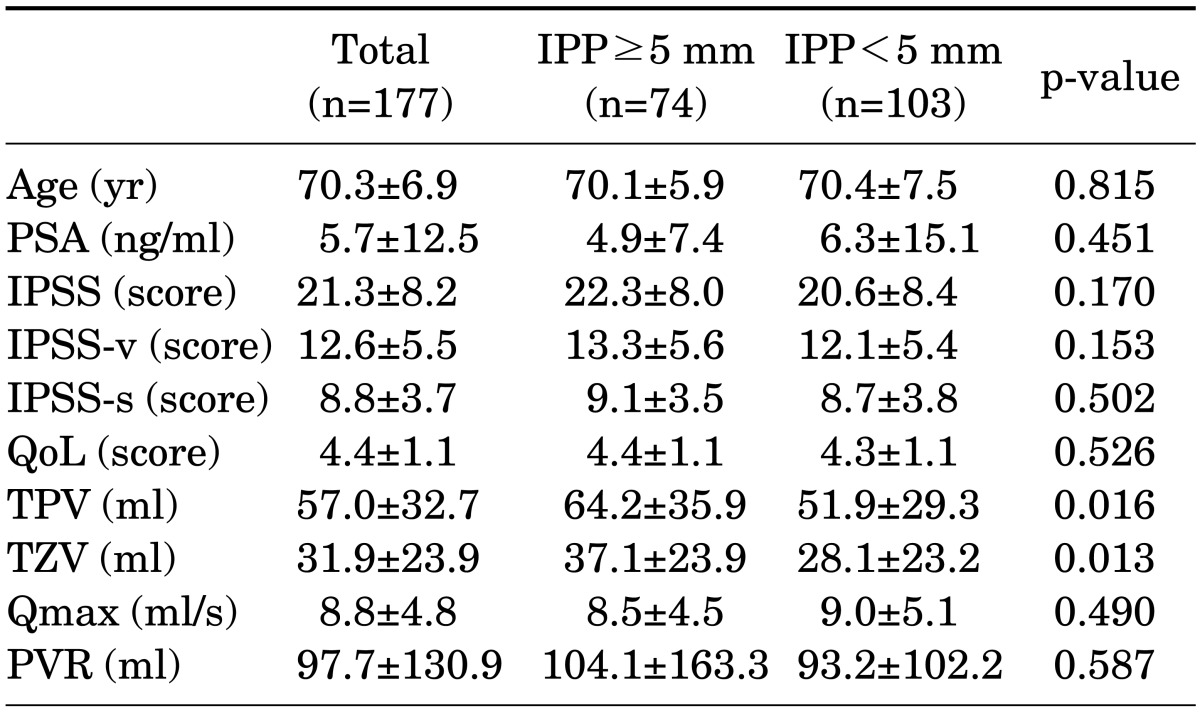

Among 249 patients who underwent TURP, 177 patients with a possible follow-up of at least 6 months fulfilled the protocol. The preoperative characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. Of the 177 patients, 74 presented with significant IPP and 103 presented with no significant IPP. The TPV and TZV in the significant IPP group were significantly larger than in the group with no significant IPP (p=0.016 and 0.013, respectively). The significant IPP group had a mean (±SD) TPV of 64.2 (±35.9) ml and a mean (±SD) TZV of 37.1 (±23.9) ml. In the no significant IPP group, the mean (±SD) TPV was 51.9 (±29.3) ml and the mean (±SD) TZV was 28.1 (±23.2) ml. No significant differences were found between the two groups in other preoperative factors, such as patient age, PSA, IPSS, IPSS-v, IPSS-s, QoL score, Qmax, and PVR.

TABLE 1.

Preoperative characteristics of the study population

Values are presented as mean±SD.

SD, standard deviation; IPP, intravesical prostatic protrusion; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score; IPSS-s, storage symptom score of IPSS; IPSS-v, voiding symptom score of IPSS; QoL, quality-of-life score; TPV, total prostate volume; TZV, transitional zone volume; Qmax, maximum urinary flow rate; PVR, postvoid residual urine.

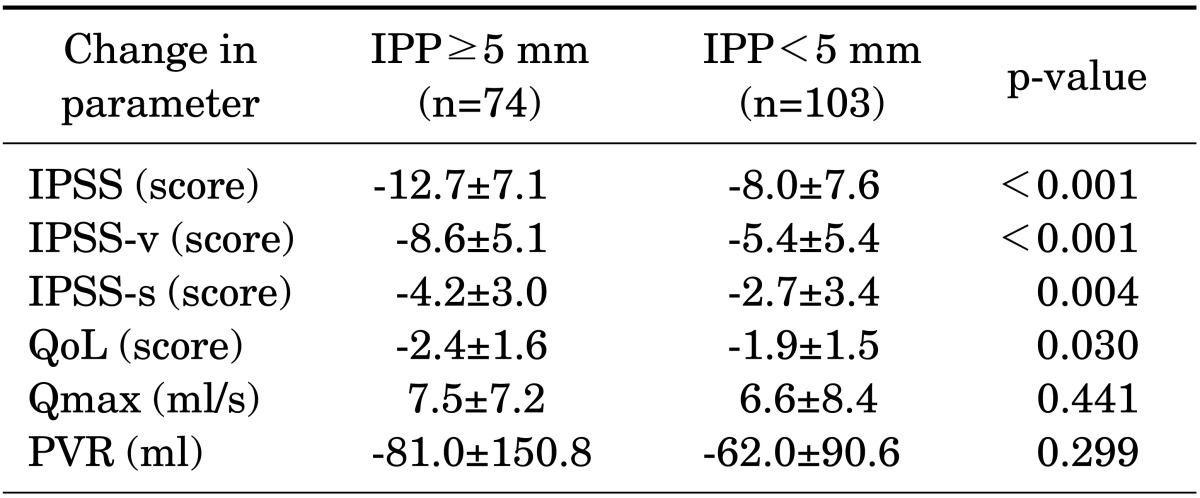

After TURP, the mean changes in IPSS, IPSS-v, IPSS-s, and QoL score of the significant IPP group were greater than those of the group with no significant IPP (p<0.001, p<0.001, p=0.004, and p=0.030, respectively). Changes in Qmax and PVR did not differ significantly between the two groups (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Postoperative changes in clinical outcomes in the two groups

Values are presented as mean±SD.

SD, standard deviation; IPP, intravesical prostatic protrusion; IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score; IPSS-s, storage symptom score of IPSS; IPSS-v, voiding symptom score of IPSS; QoL, quality-of-life score; Qmax, maximum urinary flow rate; PVR, postvoid residual urine.

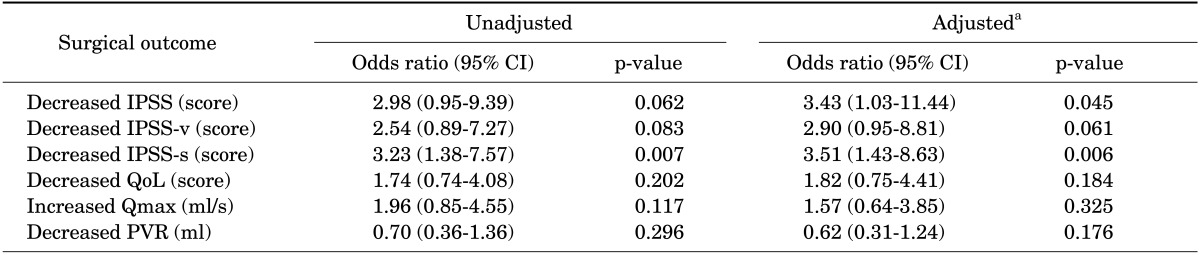

The univariate and multivariate associations between significant IPP and improved surgical outcomes are shown in Table 3. In the univariate logistic analysis, the odds ratio (OR) of decreased IPSS-s in the significant IPP group was 3.23 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.38 to 7.57; p=0.007). After adjustment for age, PSA level, TPV, and TZV, the ORs of decreased IPSS and IPSS-s in the significant IPP group were 3.43 (95% CI, 1.03 to 11.44) and 3.51 (95% CI, 1.43 to 8.63), respectively (p=0.045 and 0.006, respectively). That is, significant IPP remained independently associated with decreased IPSS and IPSS-s.

TABLE 3.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis for the relationship between significant IPP and improved surgical outcomes

IPP, intravesical prostatic protrusion; CI, confidence interval; IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score; IPSS-v, voiding symptom score of IPSS; IPSS-s, storage symptom score of IPSS; QoL, quality-of-life score; Qmax, maximum urinary flow rate; PVR, postvoid residual urine.

a:For age, prostate-specific antigen level, total prostate volume, and transitional zone volume.

DISCUSSION

IPP occurs as the prostate expands into the bladder along the plane of least resistance and is generally caused by enlargement of the median lobe with or without enlargement of the lateral lobes [10-12]. This protrusion of the prostate may lead to a ball-valve type of obstruction, which disrupts the funneling effect of the bladder neck to increase urethral resistance and causes dyskinetic movement of the bladder during voiding [10,12,13,15].

There have been some reports about IPP and its clinical importance. Chia et al. [12] showed that an IPP of more than 10 mm was associated with a higher BOO index than an IPP of 10 mm or less in patients with BOO confirmed by pressure-flow study; thus, the IPP correlated well with the severity of obstruction. Furthermore, they reported that IPP was a better and more reliable predictor of BOO than were the other variables assessed, such as age, IPSS, QoL score, Qmax, PVR, and prostate volume. Tan and Foo [9] reported that patients with an IPP of 5 mm or less might benefit from a TWOC, but that patients with an IPP of 10 mm or more were less likely to do so and would require a more definitive surgical procedure. Similarly, Mariappan et al. [10] suggested that the IPP appeared to strongly predict the outcome of a TWOC in AUR patients receiving alpha-blockers before a TWOC.

Lee et al. [11] considered the IPP as a predictor of clinical progression in benign prostatic enlargement for men undergoing nonsurgical treatment. Keqin et al. [13] also concluded that BOO and impaired detrusor function in patients with significant IPP (greater than 10 mm) are more severe, and men of this group with AUR were more likely to benefit from early surgical treatment. The results of Lieber et al. [16] indicated that the IPP was significantly correlated with greater prostate volume, higher obstructive symptoms, and lower peak urinary flow rates, which suggests that it might have clinical usefulness in predicting the need for treatment. However, we could not find any report that referred to the relationship between IPP and surgical outcomes.

Commonly, not all patients who undergo an operation for BPH obtain results that are personally satisfactory. If the postoperative improvement in symptoms could be predicted before surgery, it would be very helpful for making plans for surgical therapy. It is widely accepted that some preoperative factors such as symptomatic large prostatic adenoma and urodynamically obstructive BPH can predict a satisfactory surgical outcome, and that other factors such as a small adenoma, uncertain irritative symptoms, and detrusor underactivity make the symptoms become worse [6]. We expect that together with traditionally accepted preoperative parameters, the IPP can help to predict a better surgical result. In the present study, TURP in the group with significant IPP (≥5 mm) resulted in a reduction of IPSS (-12.7 points), IPSS-v (-8.6 points), IPSS-s (-4.2 points), and QoL (-2.4 points) scores on average, showing statistical differences with the group with insignificant IPP. Postoperative changes in Qmax and PVR were not significantly different between the two groups, however (Table 2). In general, TURP is known to result in substantial improvements in Qmax and PVR as well as in the IPSS and QoL [17-21]. In our study, although there was a certain improvement in Qmax and PVR in both the significant IPP group and the no significant IPP group after TURP, IPP did not predict a better surgical outcome of Qmax and PVR. Also, in the multivariate analysis, significant IPP was chiefly associated with the symptoms score rather than the uroflow variables. There was particularly a close connection between significant IPP and improvement in the IPSS and IPSS-s (OR, 3.43 and 3.51; p=0.045 and 0.006, respectively) (Table 3). We propose that the strong relationship between significant IPP and decreased IPSS-s may be because irritation of the bladder neck and trigone by intravesical protrusion might worsen the prominent storage symptoms [22].

The question that must be asked is how TPV and TZV exerted an influence on the present results, because TPV and TZV were shown to differ significantly between the two groups in the comparison of preoperative characteristics (Table 1). When the relationship between significant IPP and improved surgical outcomes was analyzed by multivariate logistic analysis, adjustment for TPV and TZV could make this analysis independent of an influence of TPV and TZV.

There were several limitations to our study. First, because this was a multicenter and retrospective study, the operative procedures for each patient were not the same. Moreover, the measurements made by use of TRUS, voiding uroflowmetry, and bladder scans might have been inconsistent among the institutions, although we believe that the measurements were within acceptable error ranges. Second, we could not collect information on side effects, such as urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction. It might be valuable to inquire into the relation between IPP and postoperative side effects. Last, our results were elicited from a 6-month follow-up period, not long-term follow-up. Because the symptomatic improvement provided by TURP is known to deteriorate gradually with time [23], further study with long-term follow-up is needed.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, IPP is an independent parameter for predicting postoperative outcomes in BPH patients who undergo TURP. Therefore, surgeons can expect better postoperative outcomes in terms of changes in IPSS and IPSS-s in patients with significant IPP.

Footnotes

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Madersbacher S, Marberger M. Is transurethral resection of the prostate still justified? BJU Int. 1999;83:227–237. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madersbacher S, Lackner J, Brossner C, Rohlich M, Stancik I, Willinger M, et al. Reoperation, myocardial infarction and mortality after transurethral and open prostatectomy: a nation-wide, long-term analysis of 23,123 cases. Eur Urol. 2005;47:499–504. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reich O, Gratzke C, Bachmann A, Seitz M, Schlenker B, Hermanek P, et al. Morbidity, mortality and early outcome of transurethral resection of the prostate: a prospective multicenter evaluation of 10,654 patients. J Urol. 2008;180:246–249. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ameda K, Koyanagi T, Nantani M, Taniguchi K, Matsuno T. The relevance of preoperative cystometrography in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia: correlating the findings with clinical features and outcome after prostatectomy. J Urol. 1994;152(2 Pt 1):443–447. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32759-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paez Borda A, Lujan Galan M, Martin Oses E, Llanes Gonzalez L, Berenguer Sanchez A. Predictive factors on postoperative quality of life in transurethral resection of prostatic adenoma. Arch Esp Urol. 1998;51:409–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuo HC, Chang SC, Hsu T. Predictive factors for successful surgical outcome of benign prostatic hypertrophy. Eur Urol. 1993;24:12–19. doi: 10.1159/000474255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milonas D, Saferis V, Jievaltas M. Transition zone index and bothersomeness of voiding symptoms as predictors of early unfavorable outcomes after transurethral resection of prostate. Urol Int. 2008;81:421–426. doi: 10.1159/000167840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seki N, Takei M, Yamaguchi A, Naito S. Analysis of prognostic factors regarding the outcome after a transurethral resection for symptomatic benign prostatic enlargement. Neurourol Urodyn. 2006;25:428–432. doi: 10.1002/nau.20262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan YH, Foo KT. Intravesical prostatic protrusion predicts the outcome of a trial without catheter following acute urine retention. J Urol. 2003;170(6 Pt 1):2339–2341. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000095474.86981.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mariappan P, Brown DJ, McNeill AS. Intravesical prostatic protrusion is better than prostate volume in predicting the outcome of trial without catheter in white men presenting with acute urinary retention: a prospective clinical study. J Urol. 2007;178:573–577. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee LS, Sim HG, Lim KB, Wang D, Foo KT. Intravesical prostatic protrusion predicts clinical progression of benign prostatic enlargement in patients receiving medical treatment. Int J Urol. 2010;17:69–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2009.02409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chia SJ, Heng CT, Chan SP, Foo KT. Correlation of intravesical prostatic protrusion with bladder outlet obstruction. BJU Int. 2003;91:371–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keqin Z, Zhishun X, Jing Z, Haixin W, Dongqing Z, Benkang S. Clinical significance of intravesical prostatic protrusion in patients with benign prostatic enlargement. Urology. 2007;70:1096–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim KB, Ho H, Foo KT, Wong MY, Fook-Chong S. Comparison of intravesical prostatic protrusion, prostate volume and serum prostatic-specific antigen in the evaluation of bladder outlet obstruction. Int J Urol. 2006;13:1509–1513. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuo HC. Clinical prostate score for diagnosis of bladder outlet obstruction by prostate measurements and uroflowmetry. Urology. 1999;54:90–96. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lieber MM, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, St Sauver JL, Girman CJ, Jacobsen SJ. Intravesical prostatic protrusion in men in Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Urol. 2009;182:2819–2824. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilling PJ, Mackey M, Cresswell M, Kennett K, Kabalin JN, Fraundorfer MR. Holmium laser versus transurethral resection of the prostate: a randomized prospective trial with 1-year followup. J Urol. 1999;162:1640–1644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan AH, Gilling PJ, Kennett KM, Frampton C, Westenberg AM, Fraundorfer MR. A randomized trial comparing holmium laser enucleation of the prostate with transurethral resection of the prostate for the treatment of bladder outlet obstruction secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia in large glands (40 to 200 grams) J Urol. 2003;170(4 Pt 1):1270–1274. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000086948.55973.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montorsi F, Naspro R, Salonia A, Suardi N, Briganti A, Zanoni M, et al. Holmium laser enucleation versus transurethral resection of the prostate: results from a 2-center, prospective, randomized trial in patients with obstructive benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2004;172(5 Pt 1):1926–1929. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000140501.68841.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mattiasson A, Wagrell L, Schelin S, Nordling J, Richthoff J, Magnusson B, et al. Five-year follow-up of feedback microwave thermotherapy versus TURP for clinical BPH: a prospective randomized multicenter study. Urology. 2007;69:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.08.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horasanli K, Silay MS, Altay B, Tanriverdi O, Sarica K, Miroglu C. Photoselective potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser vaporization versus transurethral resection of the prostate for prostates larger than 70 ml: a short-term prospective randomized trial. Urology. 2008;71:247–251. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JM, Chung H, Kim TW, Kim HS, Wang JH, Yang SK. The correlation of intravesical prostatic protrusion with storage symptoms, as measured by transrectal ultrasound. Korean J Urol. 2008;49:145–149. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masumori N, Furuya R, Tanaka Y, Furuya S, Ogura H, Tsukamoto T. The 12-year symptomatic outcome of transurethral resection of the prostate for patients with lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic obstruction compared to the urodynamic findings before surgery. BJU Int. 2010;105:1429–1433. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]