Abstract

Myiasis occurs when living tissues of mammals are invaded by eggs or larvae of flies, mainly from the order of Diptera. Most of the previousty reported cases are in the tropics and they were usually associated with inadequate personal hygiene, sometimes with poor manual dexterity. This report describes two cases of oral myiasis in cerebral palsy patients in Seremban General Hospital, Malaysia. This article also discusses the therapeutic property of maggots and highlights the importance of oral health care in the special needs patients.

Keywords: Oral myiasis, cerebral palsy, case report

Introduction

Myiasis is defined as infestation of live human and vertebrate animals with dipterous larvae which feed on the host’s dead or living tissue, liquid body substances, or ingested food (1).

The incidence of oral myiasis is rare, even in developing countries (2). The predisposing factors include severe halitosis and factors that favour persistent non-closure of the mouth (3).

Cases of oral myiasis have been reported to occur following dental extraction (4), nosocomial infection (5), in drug addicts (6), following visits to tropical countries (2,7), and in psychiatric patients (3). Myiasis is not uncommonly seen in chronic putrid lesions of the mouth such as the squamous cell carcinoma especially during the late stage.

This report describes two cases of oral myiasis in Malaysia which involved patients with cerebral palsy.

CASE REPORTS

Case No.1

A 15 year old Chinese boy with cerebral palsy was seen at the Casualty Department, Seremban General Hospital. He presented with persistent mouth opening and poor oral hygiene. Intraoral examination revealed a 2 cm by 2 cm perforation of the anterior palate, about 2 mm from the gingival margin of the upper right central incisor. The cavity was filled with hundreds of maggots.

The first attempt was to flush the cavity with normal saline which proved ineffective. A cotton bud impregnated with turpentine was then placed at the opening of the cavity for 10 to 15 minutes. Dozens of maggots ‘rushed’ out from the cavity. This procedure was performed out twice daily.

By the third day, the oral cavity was free from maggots. However, it was then noted that the maggots started to appear from the patient’s right ear. He was then referred to the Ear, Nose and Throat Department for further management. However, he failed to attend the review clinic.

Case No.2

A 19 year old Indian boy with cerebral palsy was referred to the Specialist Dental Clinic, Seremban General Hospital by a medical officer. This boy presented with a 1 cm x 1 cm perforation of the palate adjacent to the upper left lateral incisor. He too had persistent mouth opening and poor oral hygiene with unpleasant odour. He lives with his elderly grandmother who neglected his oral hygiene.

As in the first case, the cavity was filled with maggots. The same method of cleansing was performed. It took two days to get the cavity cleaned and free from the maggots. He was then discharged. He too failed to attend the review appointment.

For both cases, broad spectrum amoxycillin 250 mg three times daily was prescribed as there were signs of infection. Oral hygiene instructions and reinforcement (to the parents and guardians) was carried out extensively. The parents and guardians were given extensive hygiene instruction and reinforcements.

Discussion

Oral myiasis can either be primary or occasionally, secondary to nasal involvement, especially when the maggots penetrate to the paranasal sinuses or palate (4). Primary oral myiasis commonly affects the anterior part of the mouth particularly the palate (4).

The classification of myiasis is as follows (8):

Those in which the larvae live outside the body

Those in which the larvae burrow into unbroken skin and develop under it.

Those which live in the intestinal or urinary passages.

Those in which eggs or young larvae are deposited in the wounds or natural cavities in the body.

These two case reports correlates with the fourth group in the above classification.

It was predicted that the flies were attracted to the bad mouth odour due to neglected oral hygiene or fermenting food debris. Persistent mouth opening facilitates the deposition of the eggs by the adult fly. Conditions which are likely to cause prolonged mouth opening include mouth breathing during sleep, senility, alcoholism, mental retardation and hemiplegia and cerebral palsy (1).

Entomology

The genera commonly reported are Sarchophagdae and Muscidae from the Diptera order (9). The life cycle of a fly begins with the egg stage followed by the larva, the pupa and finally the adult fly.

Sood et al described that the larva can be divided into three stages depending upon the size and life span (9). During the first and second stage, the larva has segmental hooks which are directed backward. This hooks helps the larva to anchor itself to the surrounding tissue. The presence of these hooks made removal of the larva from its host difficult.

The larval stage lasts from six to eight days in which period they are parasitic to human beings. They are photophobic and therefore tend to hide themselves deep into the tissues and also to secure a suitable niche to develop into pupa.

Sood et al, further mentioned that the larvae release toxins to destroy the host tissue (9). Proteolytic enzymes released by the surrounding bacteria decompose the tissue and the larvae feed on this rotten tissue (8). The infected tissue frequently releases foul smelling discharge. As described in case I the interaction of toxin or enzyme released by the larvae-bacteria can also cause bony erosion (8).

Treatment

Treatment comprises systemic and local measures. Systemic treatment includes broadspectrum antibiotics such as ampicillin and amoxycillin especially when the wound is secondarily infected (10).

Topical treatment consists of application of turpentine larvicidal drug like Negasunt (by Bayer) (3), mineral oil, ether, chloroform, ethyl chloride, mercuric chloride, creosote, saline, systemic butazolidine or thiobendazole and removal of the larvae (4,5).

Turpentine is a toxic chemical as it can induce tissue necrosis. When applied topically, it can produce epithelial hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis and ulceration (11,12,13). However, the damage is reversible, the hyperplasia will only persist when the stimulus is continuously applied and regresses once it is withdrawn (11).

Maggot Debridement Therapy

Despite frequently being associated with dirty environment, the maggots can be used therapeutically to debride and enhance healing in chronic wounds such as the pressure ulcers and venous stasis ulcers. The maggots clear away the dead and necrotic tissue and at the same time secrete substance such as allantoin, which promotes wound healing (3).

The practice of using maggots to treat bone and soft tissue infections was established especially in North America since the 1930s. The maggots are grown and kept in special, sterile containers prior to being used.

Oral health care in special needs patients

Special needs patients include patients with mental and/or physical disability. Most of these patients have difficulties in maintaining good oral hygiene due to poor manual dexterity, parents/guardians are too busy concentrating on the patients’ social or other health aspects, parents or guardians are not aware of the importance of oral hygiene or have difficulty in gaining access to a dental clinic.

A special needs patient should be exposed to the dental intervention as early as possible to promote co-operation and confidence and to prevent disease.

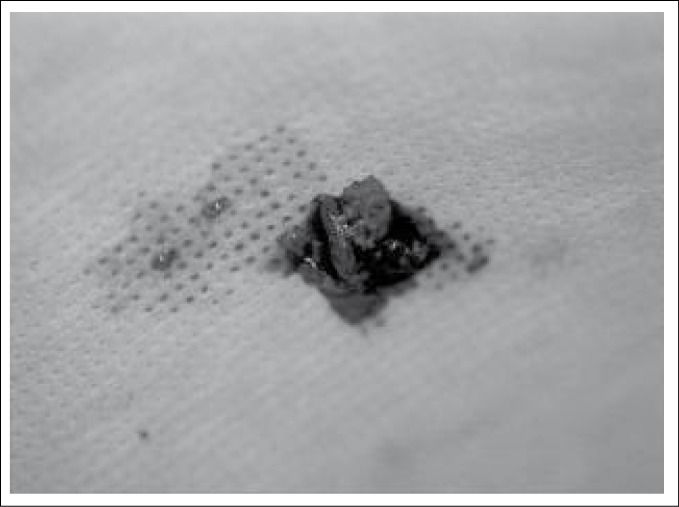

Figure 1 :

Show maggots attached to tissue after excavation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Malcolm Harris, Head and Consultant, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Eastman Dental Institute, London, for his support and advice.

Reference

- 1.Zumpt F. In: Myiasis in man and animals in the Old World. Zumpt F, editor. London: Butterworth; 1965. p. 267. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Novelli MR, Haddock A, Eveson JW. Orofacial myiasis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;31:36–37. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(93)90095-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henry J. Oral Myiasis. A case study. Dent Update. 1996;23(9):372–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bozzo L, Lima IA, de Almaeida OS, et al. Oral myiasis caused by sarcophagidae in an extraction wound. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1992;74:733–735. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90399-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Josephson RL, Krajden S. An unusual nosocomial infection: nasotracheal myiasis. J Otolaryngol. 1993;22(1):46–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fotedar R, Banerjee U, Verma AK. Human cutaneous myiasis due to mixed infestation in a drug addict. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1991;85(3):339–340. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1991.11812570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felices RR, Ogbureke KUE. Oral Myiasis. Report of case and review of management. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;54:219–220. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(96)90452-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim ST. Oral myiasis - a review. Singapore Dent J. 1974;13(2):33–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sood VP, Kakar PK, Wattal BL. Myiasis in otorhinolaryngology with entomological aspects. J Laryngol Otol. 1976;90(4):393–399. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100082219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah HA, Dayal PK. Dental myiasis. J. Oral Med. 1984;39:210–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erfan F. Gingival myiasis caused by Diptera (sarcophaga) Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1980;49:148–150. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(80)90307-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeltser R, Lustmann J. Oral myiasis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;18:288–289. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(89)80150-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erol B, Unlu G, Balci K, Tanrikulu R. Oral myiasis caused by hypoderma bovis larvae in a child: a case report. J Oral Sci. 2000;42(4):247–249. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.42.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh I, Gathwala G, Yadav SPS, et al. Myiasis in children:the Indian perspective. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1993;25:127–131. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(93)90045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhoyar SC, Mishra YC. Oral myiasis caused by diptera in epileptic patient. J. Indian Dent Assoc. 1986;58:535–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craig GT, Franklin CD. The effect of turpentine on hamster cheek pouch mucosa: a model of epithelial hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis. J Oral Pathol. 1977;6:268–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1977.tb01649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shearer BH, Jenkinson HF, McMillan MD. Changes in cytokeratins following treatment of hamster cheek pouch epithelia with hyperplastic or neoplastic agents. J Oral Pathol Med. 1994;23:149–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1994.tb01104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willoughby SG, Hopps RM, Johnson NW. Changes in the rate of epithelial proliferation of rat oral mucosa in response to acute inflammation induced by turpentine. Arch Oral Biol. 1986;31(3):193–199. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(86)90127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]