Abstract

The Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research implemented the “Studio” Program in 2007 to bring together experts to provide free, structured, project-specific feedback for medical researchers. Studios are a series of integrated, dynamic, and interactive roundtable discussions that bring relevant research experts from diverse academic disciplines together to focus on a specific research project at a specific stage. Vanderbilt’s Clinical and Translational Science Award supports the program, which is designed to improve the quality and impact of biomedical research. In this article, the authors describe the program’s design, and they provide an evaluation of its first four years.

After an investigator completes a brief online studio application, a studio “manager” reviews the request, assembles a panel of 3 to 6 experts (research faculty from multiple disciplines), and circulates the pre-review materials electronically. Investigators can request one of seven studio formats: hypothesis generation, study design, grant review, implementation, analysis and interpretation, manuscript review, or translation. A studio moderator leads each studio session, managing the time (90 minutes) and discussion to optimize the usefulness of the session for the investigator.

Feedback from the 157 studio sessions in the first four years has been overwhelmingly positive. Investigators have indicated that their studios have improved the quality of their science (99%; 121/122 responses), and experts have reported that the studios have been a valuable use of their time (98%; 398/406 responses).

To achieve the health goals of the 21st century, researchers from multiple disciplines must bridge their differences and together address the challenging problems that face us. -- The Institute of Medicine, 20011

In 2005, the Institute of Medicine and the National Academy of Engineering called for a more robust engagement between medicine and systems engineering, management science, and information science to facilitate more rigorous, efficient, modern methods of research.2 Fundamental to the necessary expansion and interdisciplinary character of the successful future clinical research enterprise will be the development and support of clinical investigators who are not only capable of rigorous hypothesis generation, study design, and data analysis within their research area, but also proficient at moving beyond their own discipline to integrate advances in other disciplines to implement, evaluate, and spread creative interdisciplinary solutions. However, developing a formal infrastructure to provide, manage, and fund this transformed research process across academic disciplines has been challenging for academic health centers.

In 2007, we developed a novel model at Vanderbilt University specifically to address these challenges, based on the premise that focused, timely, expert guidance from faculty representing multiple perspectives and disciplines would improve the quality and potential impact of today’s clinical and translational research. As part of Vanderbilt’s National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) grant and its program, Translating Discovery into Practice, we invested the resources and organizational structure to implement and evaluate an innovative model of internal research support, which we have called a “Studio.” Herein we describe the Studio Program as well as the results of our evaluation of its first four years.

Studio Definition and Purpose

The Studios are a series of integrated, dynamic roundtable discussions that bring together relevant research experts from diverse academic disciplines to focus on a specific project or investigation at a specific stage of research. These sessions are intended to refine hypotheses and research questions; to promote the most appropriate and most rigorous study designs and research methods; to assure the most effective and efficient approaches to study implementation; to examine and consider new study analyses in an effort to maximize both the amount and the rigor of information a project generates and to facilitate the translation of research findings into publication, practice, and policy.

We have classified studios into two broad categories for purposes of administrative management. The “bench to bedside” (hereafter referred to as T1) Studio Program captures research and proposed research that involve uncovering pathophysiology and mechanisms of disease, as well as early-phase feasibility, safety, and efficacy trials. These T1 Studios include the type of research typically conducted within the general clinical research center. The “bedside to practice and policy” (hereafter referred to as T2) Studio Program captures research and proposed research that involve clinical and comparative effectiveness research, epidemiology, health services research, health behavior and health education research, implementation science, community-based research, and health policy.

Studio Management

Key personnel are the two studio directors—one for T1 research (I.B.) and one for T2 research (R.S.D.)—plus, studio managers (T.T.H. and L.R.B.), and studio moderators (see “Studio types and expert panels” below). The studio directors (two senior research faculty members) consult with the studio managers to examine studio requests to assure that each request is both appropriate and sufficiently focused for a successful studio session. Studio directors also work with the studio managers to identify a studio moderator who is suitable to lead a discussion on the given topic and to select appropriate faculty experts. Finally, the studio directors guide program evaluation. The studio managers have experience in different facets of clinical research (e.g., clinical epidemiology/trials, health services research, community and behavioral health), hold master’s degrees in public health, and devote 50% of their time to studio work. The studio managers schedule the studio sessions, compile the expert review forms and notes from each session into a report with useful feedback for the requesting investigator (hereafter simply “investigator”), implement program evaluation, and use studio evaluation feedback to continually improve the Studio Program and its processes. The CTSA primary investigator (G.R.B) also sends letters to department chairs semi-annually to recognize repeat participants (experts, moderators) for their contribution (in the form of institutional service), which factors into faculty performance reviews.

Studio Processes and Description

Studios are available, free of charge, to all Vanderbilt and Meharry Medical College investigators, and we put no limit on the number of studio sessions an investigator or department can request. Meharry Medical College and Vanderbilt University are funded jointly through the CTSA grant and since 1999 have had a formal alliance to support and promote collaborative research. List 1 provides a summary of the studio process.

List 1.

Steps in the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (VICTR) Studio Program

|

Studios scheduled between 8am and 9am or 11am and 1pm include a meal.

Studio requests

Investigators who believe their research might benefit from rigorous, interdisciplinary review may request a studio on a voluntary basis at any stage of their project. The CTSA Scientific Review Committee, which allocates pilot grant resources, may also refer investigators for a studio. Either way, all investigators initiate the process by completing an online studio request form that takes less than 20 minutes to complete. This form, built into StarBRITE,3 the Vanderbilt one-stop, Web-based research portal, requires investigators to provide a brief summary of their project, as well as the specific questions that they would like the experts to help answer. Within one to three business days of submission, one of the studio managers contacts the investigator to start the scheduling process. The studio session is scheduled for a date approximately three to six weeks after the request, depending both on the availability of the investigator and panel members and on the urgency of the need. Although the studio managers do not reject applications, they may ask the investigator to defer the studio until he/she is more prepared.

Studio types and expert panels

Investigators select one of seven studio types: hypothesis generation, study design, grant review, implementation, analysis and interpretation, manuscript review, or translation (Table 1). In addition, investigators are also asked to suggest faculty experts either by name or by specific area of expertise (e.g., a biostatistician with expertise in propensity score analysis). The studio directors (working with one of the studio managers) identify, based on their personal knowledge of local expertise, additional experts who are appropriate for the stage and focus of the research. They also conduct a PubMed search of Vanderbilt investigators and/or search an NIH database listing the 553 Vanderbilt faculty members who have served on one or more NIH study sections (i.e., grant review committees) in the past 10 years. Members of a core team of senior faculty associated with the Studio Program (CTSA leadership) also serve as experts.

Table 1.

Description of 7 Studio Types*, University of Vanderbilt School of Medicine

| Studio type | Description |

|---|---|

| Hypothesis generation studio | Assists investigators with generating clear, concise, meaningful, and innovative research questions and hypotheses that will ultimately lead to funded, executed, productive projects |

| Study design studio | Assists investigators with developing improved research protocols that take advantage of the breadth of study design options available to address, as effectively as possible, the specific research hypotheses |

| Grant review studio | Assists investigators by critically reviewing the grant application to enhance the chance of funding; examines specifically the scope of the specific aims, the background and significance, the preliminary studies, and the research design/methods; functions as an internal study section to make the application more competitive |

| Implementation studio | Assists investigators with executing and monitoring research projects that adhere to the best standards in research methods |

| Analysis and interpretation studio | Assists investigators with analyzing and interpreting study data and findings, generating subsequent hypotheses and research questions, and identifying insights that could inform theories and understandings for further basic science, clinical research, and/or population-based or community research; does not supplant investigators’ responsibility to plan or conduct statistical analyses, nor provide the support necessary to fully analyze study data; does provide additional ideas and suggestions regarding the planned analyses; assists with the interpretation and communication of results |

| Manuscript review studio | Assists investigators in preparing a manuscript to enhance the chance of publication in a high-impact journal; helps target appropriate journals for publication and assists investigators in presenting the data in the most compelling manner; functions as an internal pre-review to improve clarity, to fix obvious errors, to strengthen the focus and logic of the story, and to suggest better ways of graphing the results and presenting tables |

| Translation studio | Assists investigators with examining the implications of their research in the context of the existing body of knowledge; helps to answer the following questions (among others): What new information has been added? How might the data influence best practices in the community? What additional research should follow?; helps investigators determine what application or relevance their research may have in the community, how best to disseminate relevant findings into practice, and how to use findings to inform future research hypotheses |

Vanderbilt’s Clinical and Translational Science Award grant funds most of these interactive dynamic roundtable discussions, which bring relevant research experts from diverse academic disciplines together to focus on a specific research project at a specific stage in an effort to assist investigators and improve science. Institutional monies support the grant review studio and any studio focusing on a project that involves animal research.

Most experts are Vanderbilt or Meharry faculty members, but occasionally external experts participate, usually by phone. Studio managers consider previous expert participation to avoid overtaxing any individual faculty member. Junior faculty members are purposely invited to participate as experts for the educational or professional development value of the experience. The studio manager recruits a senior investigator who has both experience with the studio process and expertise in the type of research being discussed at the studio to be the moderator. New moderators receive specific instructions the first time they guide a session. The studio moderator may also assist in selecting experts, and he or she leads the session. Every studio’s expert panel includes at least one biostatistician, assigned by the Chair of the Department of Biostatistics. Also, a member of Vanderbilt’s ethics faculty reviews every studio request to determine whether the study may benefit from ethics input.

Studio sessions

Prior to each studio session, experts receive via e-mail all documentation relevant to the research. The investigator who requests the studio provides the documents including any specific questions, concerns, or areas of focus he or she has would like addressed.

Studio managers record the sessions, which are scheduled for 90 minutes. To ensure efficiency within each session and consistency across the series of studios, we developed a studio moderator checklist (See Supplemental Digital Form 1). Each studio session begins with a brief introduction of the participants and their roles/areas of expertise. Next, the moderator provides an overview of the studio’s purpose and reviews the agenda for the session. Then (with the understanding that the assembled experts have read the relevant documents before the session), the investigator provides a 15-minute summary of the project, including the specific questions, concerns, or areas of focus, he or she would like to address.

The moderator guides the discussion that follows, allowing each expert to provide feedback and ask questions. If appropriate, the moderator incorporates ethics and compliance with regulatory requirements into the discussion. The moderator’s goal is to guide the session so that it maintains focus, stays solution-oriented, and remains non-threatening. The goal is to create a safe space for interdisciplinary discussion in a context-free zone that allows for focused uninterrupted thinking. We define “context-free zone” as a neutral environment, away from one’s office, laboratory, department, and home that allows for more creative thinking. Although studio sessions are not open to the community, interested parties may attend and observe, provided the investigator agrees. At the conclusion of the session, the moderator asks for final comments and summaries and attempts to resolve any conflicting advice. Before leaving the room, experts are expected to complete the “Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (VICTR) Expert’s Comments Form,” which requires them to provide a brief, free-text evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses of the studio research, (See Supplemental Digital Form 2).

After each studio session, the studio manager compiles the recommendations of the experts and within a few days provides the investigator with a transcript and a summary of the session.

Studio Costs and Funding

Operating costs for the Studio Program result from three basic expenses: the studio managers’ salaries, the honorarium for the experts and moderator, and, when appropriate, meals for participants. To demonstrate that we value their time, we offer all moderators and experts (regardless of their experience or expertise) $150; experts accept this honorarium when appropriate, within compliance policies for effort reporting. Participants receive meals only when studio sessions occur at breakfast or lunch time. The NIH CTSA grant serves as the primary funding mechanism of the Studio Program. Institutional funds cover grant review studios and studios that are not permitted under the CTSA guidelines (e.g., animal studies). The CTSA grant and the institution bear the entire cost of the Studio Program.

To illustrate the annual costs for the program, we examined the expenses for 2009 when we conducted 55 studios. The total cost that year was approximately $85,025. Thus, each studio session cost approximately $1,546 (Table 2). Over the first 4 years of the program, 44% of experts (362/822) have received payments, totaling $41,700. Given the value of a successful investigator and project, these costs are minimal.

Table 2.

Cost of the Studio Program, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, 2009

| Budgeted items | Costs per studio* (n = 55 in 2009) | Costs per year |

|---|---|---|

| Box lunch† | $12.50 × 10 = $125 | $6,875 |

| Experts’ honorarium | ||

| Offered | ($150 × 4 = $600) | ($33,000) |

| Accepted‡ | $264 | $14,520 |

| Moderators’ honorarium | ||

| Offered | ($150) | ($8,250) |

| Accepted‡ | $66 | $3,630 |

| Studio managers’ salary§ | ≈$1090.90 | $60,000 |

| Total | $1,545.90 | $85,025 |

Costs per studio are averaged. Some studios include fewer or more experts than 4; some studios include meals.

Studios scheduled between 8am and 9am or 11am and 1pm include a meal.

On average, 44% of experts and moderators accept the honorarium.

At Vanderbilt, this salary cost comprises 50% of the time of two managers.

Studio Promotion and Incorporation into Other Programs

We advertise and promote the Studio Program at Vanderbilt University and Meharry Medical College through various means: e-mail announcements, town hall educational sessions, research-skills workshops, and departmental overviews of Vanderbilt’s CTSA program. Further, as mentioned, the CTSA Scientific Review Committee refers investigators to studios. Lastly, faculty experienced with the Studio Program regularly encourage investigators to bring a project to the Studio Program.

In 2008, in an effort to support Masters of Science in Clinical Investigation (MSCI) trainees as they conducted their research projects, we required the studio process for first-year MSCI trainees. Each new trainee was automatically scheduled for a studio session in the first few months of his or her program. Based on positive feedback from the trainees, in 2010 we incorporated the studios into the curriculum for second-year MSCI trainees as well. We are now developing plans to incorporate the Studio Program into the Emphasis Research Program (i.e., a program of required, mentored longitudinal research4) for the medical students.

Studio Program Evaluation and Results

In an effort to continually improve the Studio Program, we evaluate each studio session. The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board has deemed this evaluation exempt research.

Evaluation process

We ask investigators, experts, and moderators to complete a survey about their perception of the value of the studio process after each studio session (See Supplemental Digital Form 3 and 4). These evaluations are not anonymous to the studio managers since an electronic linkage to the appropriate studio session is required for outcomes analysis. In January of 2011, the studio managers assessed the outcomes of the first four years of the Studio Program. They compiled data on usage, data from the investigator and expert surveys, and data on the number of CTSA grants awarded, using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Vanderbilt.5

The results presented here (and in “Lessons Learned” below) emanate from this January 2011 evaluation, as well as from the periodic discussions that studio leaders convene to gather feedback and improve the program.

Studio Program usage

We hosted a total of 157 studio sessions during the first 4 years: 11 in 2007, 44 in 2008, 55 in 2009, and 47 in 2010 (Table 3). Among the 7 studio types, study design was by far the one that investigators most often requested (n = 90). Of the 157 studio sessions, 121 were for T1 research, and 36 were for T2 research. Although assistant professors (n = 43) and fellows (n = 36) requested the most studios, the program supported the full range of medical researchers from medical students to full professors and department chairs (Table 3). Thirteen investigators have requested subsequent Studios: eleven requested a second and two have requested three sessions.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the Studio Sessions,* Requesting Investigators, and Participating Experts of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine’s Studio Program, 2007–2010

| Characteristic | No. |

|---|---|

| Studio type | |

| Hypothesis generation | 12 |

| Study design | 90 |

| Grant review | 13 |

| Implementation | 9 |

| Analysis and interpretation | 12 |

| Manuscript development | 17 |

| Translational | 4 |

| Total | 157 |

| Year of the studio | |

| 2007 | 11 |

| 2008 | 44 |

| 2009 | 55 |

| 2010 | 47 |

| Total | 157 |

| Requesting investigator’s academic rank or position | |

| Medical student | 1 |

| Nurse practitioner | 1 |

| Resident | 10 |

| Post doctoral | 2 |

| Fellow | 36 |

| Instructor | 13 |

| Assistant professor | 43 |

| Associate professor | 22 |

| Professor (including department chairs) | 18 |

| Other | 11 |

| Total | 157 |

| Participating experts’ academic rank | |

| Professor | 323 |

| Associate Professor | 179 |

| Assistant Professor | 211 |

| Senior Associate | 32 |

| Instructor | 14 |

| Biostatistician II/III | 12 |

| Fellow | 5 |

| Resident | 2 |

| Other | 44 |

| Total | 822 |

| Participating experts’ department or center | |

| Medicine† | 329 |

| Biostatistics | 187 |

| Pediatrics | 58 |

| Biomedical informatics | 19 |

| Neurology | 17 |

| Surgery | 17 |

| Psychiatry/psychology | 15 |

| Biomedical ethics | 14 |

| Center for Human Genetic Research | 14 |

| Nursing | 12 |

| Preventive medicine | 9 |

| Molecular physiology and biophysics | 9 |

| Pathology | 8 |

| Emergency medicine | 5 |

| Pharmacology | 5 |

| Radiology | 5 |

| Biomedical engineering | 3 |

| Other | 96 |

| Total | 822 |

The mean number of days from request to session from 2007–2010 was 41; the range 6 – 140.

The Department of Medicine includes numerous epidemiologists and basic scientists.

The number of studio sessions that each expert participated in ranged from 1–29. Approximately 30% of the experts participated in only one studio session; nine experts participated in 10 or more studio sessions. Except for reasons of travel or a perceived subject matter mismatch, no expert or moderator has thus far declined to participate.

Time from request to session

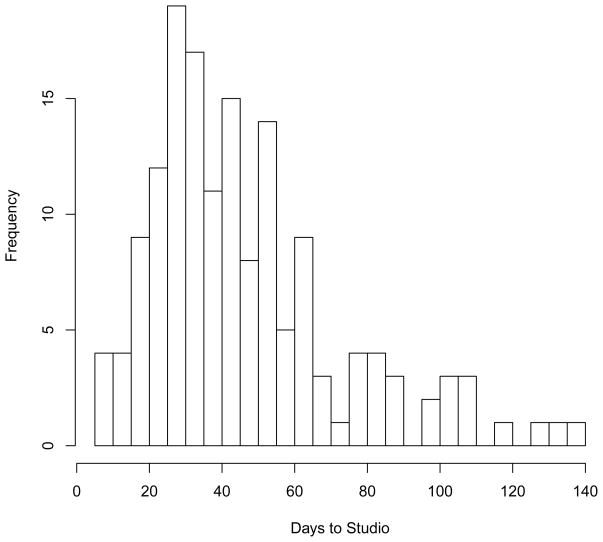

The median time from request to studio session was 41 days (95% bootstrap confidence interval: 35 – 44), with a range of 6 to 140 days; the mode was 28, inter-quartile range was 28 to 58 days (Figure 1). The period between request and session includes preparation time requested by investigators. MSCI program trainees often request that their studio sessions occur several months in the future to align better with their training schedules. The median time from request to studio session for the non-MSCI investigators was 39.0 days (range: 6–134) vs. 50.5 days (15–140) for MSCI investigators (P < 0.001). Nearly all of the investigators who completed their evaluation (98%; 117/120) agreed that the scheduling/communication for their studio session was handled in a timely and efficient manner (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Histogram of time from request to studio session for the first for years (2007–2010) of the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research Studio Program.

Table 4.

Evaluation of the University of Vanderbilt School of Medicine’s Studio Program, Based on Follow-Up Surveys of Requesting Investigators (n = 157) and participating experts (n = 822), 2007–2010*

| Survey items for investigators, with response choices | No. (%) endorsing choice |

|---|---|

| “I was satisfied with the studio session.”† | |

| Strongly agree | 59/78 (76) |

| Agree | 19/78 (24) |

| Disagree | 0 |

| Strongly disagree | 0 |

| “The studio process was worth my time.”† | |

| Strongly agree | 66/78 (85) |

| Agree | 12/78 (15) |

| Disagree | 0 |

| Strongly disagree | 0 |

| “Would you recommend a studio session to a colleague?”† | |

| Yes | 78/78 (100) |

| No | 0 |

| “The studio improved the quality of the science.” | |

| Strongly agree | 85/122 (70) |

| Agree | 36/122 (29) |

| Disagree | 1/122 (1) |

| Strongly disagree | 0 |

| “The scheduling and communication for this studio session were handled in a timely and efficient manner.” | |

| Strongly agree | 85/120 (71) |

| Agree | 32/120 (27) |

| Disagree | 2/120 (2) |

| Strongly disagree | 1/120 (1) |

| Survey item for experts, with response choices | No. (%) endorsing choice |

| “The studio process was worth my time.” | |

| Strongly agree | 238/406 (58.6) |

| Agree | 160/406 (39.4) |

| Disagree | 6/406 (1.5) |

| Strongly disagree | 2/406 (0.5) |

These results are based on the self-reported feedback from the surveys returned via e-mail. The response rate was 78% (122/157) for the investigator survey and 49% (406/822) for experts and moderators.

The first three questions in this table were added after the initial year.

Satisfaction with the Studio Program

The response rate for our survey was 78% (122/157) for investigators and 49% (406/822) for experts and moderators. Both groups perceived the studios as a valuable addition to Vanderbilt’s clinical research infrastructure (Table 4). Investigators were almost unanimously satisfied with the studio sessions. Of those who responded, all but one (121/122; 99%) agreed that the Studio Program improved the quality of their science, and all reported that they would recommend the Studio Program to their colleagues. Similarly, 98% of the experts who contributed to the Studio Program (398/406) responded in their evaluations that the process was worth their time. Experts reported anecdotally that they enjoyed participating in the intellectual debates about the formulation of research questions and the design, implementation, and analysis of specific research projects.

CTSA grants

As mentioned, Vanderbilt’s CTSA Scientific Review Committee referred investigators with pilot research proposals that were deemed not yet ready for funding to the Studio Program. Studio sessions proved effective in improving the proposal so that pilot funding was awarded on subsequent review in nearly three-fourths of the proposals; the remaining proposals were sufficiently revised through the process that the investigators refocused their efforts in a different direction.

Evaluation limitations and conclusions

Our estimation of the Studio Program’s success could be biased since those who were unsatisfied with the program might have failed (given that feedback was not completely anonymous) to complete the evaluation forms or may have been unwilling to openly criticize the program. Also, we have neither a control group, nor—to date—any long-term endpoints; however, the process improvements reported are likely to lead to long-term success.

Through our evaluation of the first four years of the VICTR Studio Program, we found that investigators have been highly satisfied with the Studio Program and have reported that the sessions have improved the quality of their science. We also found that the vast majority of faculty members selected to serve as experts reported that participating in the studios was worth their time and that they believed that their input improved the quality of the science. These are noteworthy findings since they suggest that creating an effective, widely-accepted internal research support system is possible.

Breaking Barriers

One of the goals of the academic health centers, as outlined by the CTSA program, is to remove barriers for clinical and translational researchers.6 These barriers generally fall into three categories: the research workforce, research operations, and organizational silos.7 The Studio Program offers universities and their investigators a means of overcoming each of these barriers.

The Studio Program constitutes a form of faculty development for investigators. Studio sessions provide valuable and needed support for both junior and senior investigators; the sessions help investigators to effectively develop high-quality clinical research and, in turn, succeed in academia. In particular, we have received positive feedback from the MSCI program trainees, who now enthusiastically participate in the studio process as a routine part of their research projects. The Studios therefore facilitate building the research workforce.

The Studio Program has also contributed to improving research operations, by, most significantly, bringing together study investigators and faculty with expertise in such areas as study design, data acquisition (including effective use of existing databases), measurement, study implementation, data analysis, informatics, regulatory affairs, and ethics. Rich discussion on these topics during studio sessions informs the research under consideration in an efficient and effective way.

Although investigators who bring their research to studios have mentors and receive feedback from within their laboratory or division, the studio sessions can provide deeper and broader expertise and further improve their projects. Studio leaders believe that it is vital for the experts in the studios to actually hear one another’s feedback, rather than forcing the investigator to relay one expert’s feedback to another. Without the Studio Program, investigators would face the problem of continuously resolving an endless cycle of conflicting advice that resolved previously conflicting advice. When together, experts and investigators can come to a common solution they might not have considered otherwise, that evolves from their interdisciplinary interactions. Further, bringing many experts together prevents junior investigators from becoming caught in a maelstrom of mentoring.

Lastly, studios also serve to break down the third barrier – organizational silos. As Califf suggests, silos continue to be a major challenge, “The siloed nature of academic institutions can render fundamental communication among researchers difficult”8 Studios have routinely brought together researchers with expertise in clinical and translational sciences such as biostatistics, education, engineering, epidemiology, and ethics. The Studio Program has also brought together professionals from the fields of clinical health (e.g. medicine, nursing, and allied health), informatics, management science, public health, and the social sciences (including anthropology, economics, psychology, and sociology). Finally, studios have brought together clinical investigators and scientists with expertise in basic laboratory science such as molecular physiology and biophysics, cell and developmental biology, microbiology, and pharmacology. Anecdotal evidence indicates that new synergistic collaborations have organically emerged from the Studio Program.

The studios reduce not only intra-institutional barriers, but also inter-institutional barriers. Specifically, the Studio Program has strengthened the Meharry-Vanderbilt partnership by facilitating effective collaborations and enhancing the exchange of information about institutional capabilities.

Lessons Learned

While the Studio Program has been successful, studio managers note three specific challenges to the implementation of an effective studio session. First, investigators need to be properly prepared for the session. On rare occasions, inadequate preparation has reduced the effectiveness of a session. Second, some investigators have failed to keep their presentations brief, limiting the time for feedback. Third, on one occasion, too many (n = 10) experts participated in a session and the pre-review material was underdeveloped, which reduced the value of the session. The ideal number of experts depends on the topic, the investigator, and the moderator, but we have found that 5 experts per session generally provide the right balance.

We also acknowledge that this Studio Program may not be as successful at other academic health centers that have a different academic culture or that do not have a CTSA grant or other source of support. Vanderbilt has a collaborative, generous, supporting, and open culture of inquiry in which the type of effort and interactions that are generated by the Studio Program are embraced.

Finally, the studio process as described is an ongoing, evolving program—not a static entity. We use ongoing feedback for continual improvement. However, the basic elements (see below) remain constant and serve as the guiding principles of the program.

While it is difficult to measure the impact of the studios without a control group, our experiences with the program over its first four years suggest that it has improved the research process and the quality of the science generated through at least four mechanisms. First, a diverse set of experts in a room together brainstorming about a particular research issue has allowed the Studio Program to function as an incubator, often creating a synergy that generates novel hypotheses and study design features. The moderators play an important role in making sure each expert receives time to provide input and is heard. The success of the Studio Program relies on the ability to keep existing experts returning for, and new experts willing to attend, future studio sessions.

Second, connecting investigators to collaborators with complementary expertise has established new connections among individuals who might not otherwise have met. Third, the panel of studio experts often represents more than a century of collective experience in clinical research, which creates a think-tank environment that enhances research quality and ensures appropriate protocol design and scientific rigor. Having an ethicist on the panel often helps investigators improve their research design by addressing ethical issues early in the planning phase, just as including biostatisticians helps guarantee the quality of the quantitative analyses.

Finally, the formal studio process provides a timely mechanism to gather busy experts together to assist an investigator in a focused manner. Given the very busy schedules of such experts, a single investigator acting alone would have a difficult, if not impossible, task scheduling such a discussion in a timely manner without the infrastructure and culture provided by the Studio Program.

In Table 5, we provide guidelines for implementing a Studio Program based on our experience.

Table 5.

Guidelines for Implementing a Studio Program

| Domain | Specific recommendations |

|---|---|

| Leadership support | Obtain support and funding from the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) principle investigator and/or leaders of the academic health center. A major reason that Vanderbilt’s Studio Program has been successful is that the CTSA leadership enthusiastically support it and actively recruit participants. |

| Studio manager | Hire a dedicated studio manager who has experience in clinical research. This work cannot be delegated to an administrative assistant. An administrative assistant would likely have neither the proficiency to identify experts, nor the influence to orchestrate studio sessions and subsequent evaluations. |

| Technology | Develop both an online studio-request form to expedite the process of translating studio requests into sessions and a tracking system to gather feedback for continuously improving the quality of sessions and measuring outcomes. |

| Honorarium | Provide financial reimbursement to experts and moderators for their participation in studios sessions. |

| Recruitment | Be proactive about recruiting investigators to bring their projects to studio sessions for the first few years until the Studio Program becomes automatic and part of the culture. A broad e-mail announcement is not sufficient to change the culture. |

| Preparation | Investigators must be coached on how to prepare for a studio session. Consider providing, at least for some investigators, a pre-studio-session to help them prepare. An important part of this preparation is to define a few focused questions for the experts to answer. Ensure the alignment of expectations between the experts and the investigator. |

| Culture | Build a culture of cooperation and collegiality among clinical and translational researchers and measure progress with metrics. |

In Sum

In conclusion, with the support of the CTSA grant and institutional funding, Vanderbilt has created a comprehensive, fully-funded, sustainable review and research support mechanism that provides robust interdisciplinary engagement among faculty from multiple schools and departments to improve the quality of clinical research. Investigators and participating faculty experts have enthusiastically endorsed the Studio Program.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Robertson, M.D., Vivian Siegel, Ph.D., Lynda Lane, M.S., R.N., Tonya Yarbrough, R.N., Li Wang, M.S., and Paul Harris, Ph.D. for their constructive feedback on this manuscript during a studio session.

Funding/Support: This work was supported in part by Vanderbilt Clinical and Translational Science Award grant 1 UL1 RR024975 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content for this article is available at [xxx-add links at proofs-xxx].

Other disclosures: None.

Ethical approval: The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board determined that the evaluations described in this article are exempt research.

Contributor Information

Mr. Daniel W. Byrne, Director, Quality Improvement and Program Evaluation, the Department of Biostatistics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee.

Dr. Italo Biaggioni, Professor of medicine and pharmacology, the Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee.

Dr. Gordon R. Bernard, Associate vice chancellor for research; principal investigator, the Vanderbilt Clinical and Translational Award and Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research; and professor of medicine, the Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee.

Ms. Tara T. Helmer, Research services consultant and T1 studio manager, the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, Research Support Services, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee.

Ms. Leslie R. Boone, Translational research coordinator and T2 studio manager, Vanderbilt Institute for Medicine and Public Health, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee.

Ms. Jill M. Pulley, Director, Research Support Services, and implementation manager, the Vanderbilt Clinical and Translational Science Award, Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee.

Ms. Terri Edwards, Assistant director, Research Support Services, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee.

Dr. Robert S. Dittus, Associate vice chancellor for public health and health care; director, Vanderbilt Institute for Medicine and Public Health; the Albert and Bernard Werthan Professor of Medicine, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine; and director, Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center, Veterans Affairs Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville, Tennessee.

References

- 1.Pellmar TC, Eisenberg L, editors. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Building Bridges in the Brain, Behavior, and Clinical Sciences. Bridging Disciplines in the Brain, Behavioral, and Clinical Sciences. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [Accessed April 26, 2012]. http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=9942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reid PP, Compton WD, Grossman JH, Fanjiang G, editors. Committee on Engineering and the Health Care System, Institute of Medicine and National Academy of Engineering. Building a Better Delivery System: A New Engineering/Health Care Partnership. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [Accessed April 26, 2012]. http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=11378. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris PA, Swafford JA, Edwards TL, et al. StarBRITE: The Vanderbilt University Biomedical Research Integration, Translation and Education portal. J Biomed Inform. 2011;44:655–662. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gotterer GS, O’Day D, Miller BM. The Emphasis Program: A scholarly concentrations program at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. Academic Medicine. 2010;85:1717–1724. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181e7771b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zerhouni EA, Alving B. Clinical and translational science awards: A framework for a national research agenda. Transl Res. 2006;148:4–5. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heller C, de Melo-Martin I. Clinical and Translational Science Awards: Can they increase the efficiency and speed of clinical and translational research? Acad Med. 2009;84:424–432. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819a7d81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Califf RM, Berglund L. Linking scientific discovery and better health for the nation: The first three years of the NIH’s Clinical and Translational Science Awards. Acad Med. 2010;85:457–462. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ccb74d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.