Summary

Although quality of life (QOL) is an important treatment outcome in head and neck cancer (HNC), cross-study comparisons have been hampered by the heterogeneity of measures used and the fact that reviews of HNC QOL instruments have not been comprehensive to date. We performed a systematic review of the published literature on HNC QOL instruments from 1990–2010, categorized, and reviewed the properties of the instruments using international guidelines as reference. Of the 2766 articles retrieved, 710 met the inclusion criteria and used 57 different head and neck-specific instruments to assess QOL. A review of the properties of these utilized measures and identification of areas in need of further research is presented. Given the volume and heterogeneity of QOL measures, there is no gold standard questionnaire. Therefore, when selecting instruments, researchers should consider not only psychometric properties but also research objectives, study design, and the pitfalls and benefits of combining different measures. Although great strides have been made in the assessment of QOL in HNC and researchers now have a plethora of quality instruments to choose from, more work is needed to improve the clinical utility of these measures in order to link QOL research to clinical practice. This review provides a platform for head and neck-specific instrument comparisons, with suggestions of important factors to consider in the systematic selection of QOL instruments, and is a first step towards translation of QOL assessment into the clinical scene.

Keywords: Assessment, Head and Neck Cancer, Instruments, Measures, Quality of Life, Questionnaire

Head and neck cancers (HNCs) account for only 4% of all cancer cases in the U.S;1 however, the disease and its treatment have a disproportionate impact on all aspects of patient quality of life (QOL). QOL is a multi-dimensional construct of an individual's subjective assessment of the impact of an illness or treatment on his or her physical, psychological, social, and somatic functioning and general well-being.2,3 Patients with HNC report significant and persistent physical (i.e., radionecrosis, mucositis, loss of taste, and dysphagia),4–7 functional (i.e., pain, difficulty swallowing, voice impairment, and poor dental status),8–11 and psychosocial problems (i.e., depression, disfigurement, social isolation, and delays returning to work).12–18 Given that QOL domains have been shown to predict survival among HNC patients,19–21 it is not surprising that QOL has become an important treatment outcome in HNC.22–24

QOL assessment in HNC is critical not only to the evaluation of treatment options, but also to the development of rehabilitative services and patient education materials. Despite this fact, there is a lack of understanding of the true clinical significance of QOL in HNC and how to best interpret and implement the results of research studies into clinical practice. This problem has been fueled by the lack of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) in HNC that prospectively assess QOL, the use of sometimes inappropriate measures, and the lack of a gold-standard measure to facilitate cross-study comparisons. Adding to the problem, researchers often combine QOL measures in their studies without fully understanding how they complement or conflict with each other. For example, many generic, cancer-specific, and HNC disease-specific measures have overlapping content (e.g., they assess mental and physical quality of life),3 but are often used together by investigators in the same study.

Developing a clearer understanding of the plethora of available instruments and their properties is a necessary first step towards addressing the above problems and bridging the gap between research and clinical practice. However, existing reviews of QOL instruments in the HNC literature have not been comprehensive2,25–27 in their scope. Moreover, existing QOL instrument databases, like the PROQOLID,28 are nonspecific and lack information on some instruments commonly used in HNC and subscription fees for key information (e.g., psychometric properties) in such databases, hamper their utilization among researchers with limited budgets. Furthermore, these databases, like previous reviews, often lack information on the QOL issues or domains addressed by the instruments, a key component of the instrument selection process.

According to the Scientific Advisory Committee of the Medical Outcomes Trust (SAC-MOT) for the development and validation of health outcomes questionnaires29 and other international guidelines,29–33 high-quality measures of QOL should be reliable, valid, and demonstrate responsiveness (the ability to detect change over time).29,32,33 Other characteristics to consider when evaluating measures include the conceptual and empirical basis for content generation, whether there is reasonable respondent and administrative burden, and whether the measure has been translated and validated for use in cross-cultural populations.29

We conducted a comprehensive and systematic review of QOL instruments that have been used to assess HNC patients over the past two decades and synthesized the published information on these measures using the SAC-MOT guidelines. Unlike other reviews, this review makes recommendations that take into consideration the frequency of utilization of each QOL instrument in the literature. For the purpose of this review, administrative and respondent burden were not assessed because it would require consideration of several subjective variables (disease burden, questionnaire format, response system, mode of delivery, and individual variability). Although, a number of generic measures of QOL and psychosocial functioning exist that have been used with HNC patients, our review focuses exclusively on HNC-specific instruments. By reviewing existing measures and discussing the selection of appropriate QOL instruments, with a view to making recommendations for future studies, we hope this review serves as a platform to improve QOL assessment in HNC, facilitate cross-study comparisons, and ultimately bridge the gap between research and clinical practice.

Methods

Literature Search

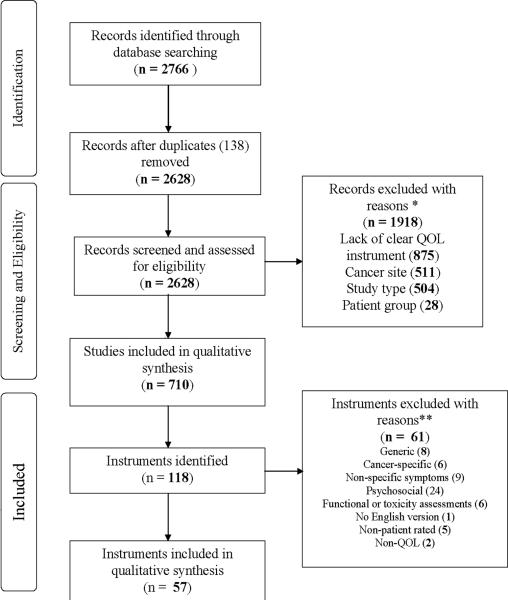

Using the following key terms—“head and neck cancer,” “quality of life,” “speech,” “voice,” “swallowing,” “appearance,” “questionnaire,” “scale,” “score,” “instrument,” and “inventory”—we conducted an electronic bibliographic search of studies from January 1990 to November 17, 2010. We searched the following databases: PubMed, Health and Psychosocial instruments, Science Citation Index/Social Sciences Citation Index, and PsycINFO (Psychological Abstracts). Non-English citations were excluded. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA34 flow chart depicting the study identification and selection process. A total of 2766 articles were identified; when duplicates were removed, 2628 articles remained. Given the large number of articles obtained, hand-searching was not performed.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of literature search. *Measures not formally developed; non-head and neck cancer sites (esophageal, lung, breast, prostate, or brain tumors); reviews, opinions, case reports, technique papers without QOL data, guidelines, surveys of healthcare practitioners, diagnostic studies, or basic science studies; healthy persons, patients with non-neoplastic conditions, or not enough HNC patients (<10% of participants). **Generic: 15D-instrument, EQ-5D, Health Status Questionnaire-12, Medical Outcomes Study-Short form (SF-12 and SF-36), Nottingham Health Profile, Sickness Impact Profile, WHOQOL-100, and WHOQOL-Bref; Cancer-specific: Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System-Short Form, EORTC QLQ-C30, FACT-G, Functional Living Index of Cancer, QL-index, Rotterdam Symptom Checklist; Non-specific symptoms (including fatigue and pain): Brief Fatigue Inventory, Condensed Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale, FACIT-F, Keller Symptom Questionnaire, Multi-dimensional Fatigue Inventory-20, McGill Pain Questionnaire, MSAS, Symptom Distress Scale, UCSF-Oral Cancer Pain Questionnaire; Psychosocial: Beck Depression Inventory, Brief Symptom Inventory, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, Dyadic Adjustment Scale, Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, Depression Inventory for Cancer v2, FACIT-Sp12, Geriatric Depression Scale, General Health Questionnaire, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Hornheider Fragebogen short form, IES, Life Satisfaction scale by Morton, Life Satisfaction scale by Watt et al., Mental Adjustment to Cancer Questionnaire, Millon Behavioral Health Inventory, Mental Health Inventory, Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale, Patient Health Questionnaire-9, Profile of Mood States, Spiritual Beliefs Inventory-15, Satisfaction of Patients Questionnaire, Spiritual Well Being Linear analog self-assessment, Zung Self-rating depression scale; Functional or toxicity: Performance Status Scale for Head and Neck, Karnofsky, World Health Organization Performance Status, Functional Outcome Swallowing Scale, Late Effects in Normal Tissues Subjective, Objective, Management and Analytic Scales, Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group Toxicity Scoring System; No English version: Trial-Specific Questionnaire; Non-patient rated: Penetration Aspiration Scale, Disfigurement/Dysfunction Scale, Observer-Rated Disfigurement Scale, QL Index, and Hamilton Depression Scale; Non-QOL: Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence

Screening and Eligibility

Identified articles were screened for inclusion using EPPI-Reviewer 4.035 software in a two-stage process. First, articles were selected and then, within those articles, the QOL instruments were identified.

Article selection

Exclusion criteria (other than the article being in a language other than English) were - study only involved cancer sites other than the head and neck, study did not use a formally developed QOL questionnaire, the article was not an original article (e.g., it was a secondary analysis), and study involved patient groups with non-malignant conditions or heterogeneous cancer populations with an insufficient number of HNC patients (i.e. healthy individuals, patients with non-neoplastic conditions, and ≤10% HNC patients).

Instrument identification

QOL instruments were selected by examining titles, abstracts, and full texts of the resulting 710 articles. The psychometric properties of the instruments selected from these articles (Figure 1) were extracted as described below. To provide a clearer picture of the general consensus on the use of the instruments amongst researchers and to investigate the possibility of a go-to instrument in each category, a tally of the frequency of use of each of the instruments that were identified in the included articles was also taken.

Abstraction of Psychometric Properties

Instruments were first categorized according to whether they were site-specific (head and neck), treatment-specific, or symptom-specific.3

At present, although there have been initiatives there is no consensus on the criteria for evaluation and selection of QOL instruments. Examples of these initiatives include the detailed evaluation criteria put forward by the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) initiative36 and the review criteria by The Scientific Advisory Committee of the Medical Outcomes Trust (SAC-MOT).29 The COSMIN checklist is a thorough checklist for evaluation of adequacy of measures and we refer readers who have narrowed their instrument choice to this checklist. However, because the aim of this review was to provide a description of the key properties of instruments to help guide researchers in choosing an instrument, we abstracted data on each instrument based on the SAC-MOT guidelines.29–33 Two independent coders gathered and synthesized the following information about each instrument. An overall quality score was not assigned because of the subjective nature of instrument selection and the unequal contribution of measurement properties to overall quality.

Description of validity - the extent to which instruments measure what they purport to measure – was divided into three categories: content (how appropriate the items are in measuring the construct of interest), criterion, which may be concurrent or predictive, refers to how well the scores of the instruments are related to other instruments of the same or related constructs, and construct validity (discriminant or convergent) evaluates the measure with variables known to be related to the construct of interest.

Description of reliability – how consistently and reproducibly the instrument measures a symptom – based on evidence of internal consistency of scale items and reproducibility (test-retest reliability or inter-rater reproducibility).

Description of the format (e.g., number of items, scale, and administration options).

Description of the interpretability (e.g., scoring methods, presence of clinically relevant methods of interpretation such as published normative data or minimum clinically important difference (MCID), time frame of assessment, and description of dimensions assessed by the instrument).

Description of the empirical basis for item content and combinations (i.e., a structure analysis; whether item response theory, factor analysis, or canonical correlational analysis was used to come up with the final set of items).

Description of whether the instrument was designed to detect changes over time (responsiveness, defined here as whether the instrument was used in a longitudinal study).

Availability of translated versions of the measures (a component of cross-cultural adaptation)

Results

Most of the studies described in the 710 articles included in this review were cross-sectional (353) or longitudinal descriptive studies (235). Few RCTs (35) met the article selection criteria. Instruments from the articles (Figure 1) were excluded if they were generic (n = 8), broadly cancer-specific i.e. not specific to the head and neck (n = 6), non-specific for symptoms, fatigue, or pain (n = 9), psychosocial (n = 24), functional (e.g., performance status) or toxicity (n = 6) instruments, screening behavioral tools (n = 2), or not patient-rated (n = 5). One instrument was excluded because the contacted author reported that the questionnaire only existed in Dutch. Thus, the final number of QOL instruments included in the review was 57.

Properties for the measures reviewed are presented by category in Tables 1–5 and are summarized briefly below. In addition, data on the number of studies that utilized a particular instrument are provided and areas in need of more research are identified based on lack of reports of questionnaire properties as outlined in the SAC-MOT guidelines.

Table 1.

Site specific (Head and neck cancer) QOL measures

| Measures | Validity | Reliability | Format (Number, scale, administration options) | Interpretability | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (Of 710 studies) | Content | Criterion | Construct | Internal consistency | Test-retest | Inter-rater | Structure | Responsiveness in HNC patients | Translations | |||

| AQLQ102 | 3 | X | X | X | X |

Items: Not reported Scale: Mixed format: 2, 3, 4, and 7 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: physical functioning, symptoms, social functioning, psychological functioning, well-being; Also contains single overall life satisfaction item Scoring: no global score Time frame of assessment: not reported |

X | ||||

| EORTC QLQ-H&N3537 | 244* | X | X | X |

Items: 35 Scale: 4 pt Likert type for all but 5 items (yes/no) |

Dimensions: Seven scales: pain, swallowing, senses, speech, social eating, social contact, sexuality Scoring: Scores transformed to 0–100 scales Time frame of assessment: past week |

I | X | X | |||

| FACT-HN40 | 86* | X | X | X† |

Items: 11 (module) and 27 (FACT-G) Scale: 5 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: physical, functional areas of performance, social functioning, relationship with physician, emotional well-being Scoring: Global and domain/module score (module score range 0–48) Time frame of assessment: past 7 days |

F | X | X | |||

| FACT-NP103 | * | X | X | X | X | X |

Items: 16 (module) and 27 (FACT-G) Scale: 5 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: physical, social/family, emotional, and functional well being and nasopharyngeal carcinoma subscale Scoring: domain score – sum of NPC subscale – range 0–64 Time frame of assessment: past 7 days |

X | X | ||

| FSCI44,45 | 3 | X | X |

Items: 15 Scale: 5 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: 3 subscales: emotional, social, and appearance Scoring: subscale scores and total skin cancer index score, standardized score range 0–100; Time frame of assessment: At present moment |

F | X | |||||

| FSH&N-SR104 | 1 | X | X |

Items: 15 + free hand item Scale: 5 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: 12 symptom categories: upper body mobility, chewing, swallowing, drooling, taste, dry mouth, eating, speech, breathing, appearance, pain, fatigue; items include an overall QOL item Scoring: scores range from 15–75 Time frame of assessment: past week |

|||||||

| H&NS105 | 1 | X | X | X |

Items: 13 Scale: 5 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: eating/swallowing, speech/communication, appearance, head and neck pain Scoring: Global and domain score, score range 0–100 Time frame of assessment: past 4 weeks |

||||||

| HNCI43 | 8 | X | X | X | X |

Items: 30 Scale: 5 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: Four domains: speech, eating, aesthetics, social disruption, an overall QOL item Scoring: score range 0–100; domain, functional, attitudinal sub-domain scores, no global score Time frame of assessment: past four weeks |

F | X | X | ||

| HNQOL41 | 27 | X | X | X |

Items: 20 Scale: 5 pt Likert type, yes/no |

Dimensions: eating, communication, pain, and emotion Scoring: Domain scores Time frame of assessment: past 4 weeks |

F | X | X | |||

| MDASI-HN42 | 2 | X | X | X | X |

Items: 9 Scale: 11 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: Swallowing/chewing, mucus, taste, voice/speech, mouth/throat sores, teeth/gum issues, choking/cough, constipation, diarrhea, hair loss, skin issues Scoring: To be used in conjunction with the 13 MDASI core and 6 interference items Time frame of assessment: past 24 hours |

F | X | X | ||

| Parotidectomy QOL Survey50 | 1 | Xf | Not reported |

Items: 8 Scale: 7 pt ordinal scale, first item with multiple answer choices, 1 freelance item |

Dimensions: Assesses frequency, duration, degree of bother, size of affected area, daily activity interference, and frequency of worry/concern caused by abnormal sensations around the ear or neck after parotidectomy Time frame of assessment: since surgery, past month |

|||||||

| QLQ - Rathmell46 | 1 | Not reported | 1 | Not reported |

Items: 13 Scale: 4- 5 answer categories |

Dimensions: Items on pain frequency/severity, eating ability, mouth dryness, taste, appetite, weight loss, speech, energy level, work, social contact, state of mind, physical appearance Time frame of assessment: past week |

X | |||||

| QOL-NPC47 | 1 | Not reported | X |

Items: 30 Scale: Linear 11 pt scale |

Dimensions: Four domains – physical, psychological, social, side effect Scoring: Domain scores |

F | X | |||||

| QOL-Thyroid51,52 | 2 | X | X |

Items: 30 Scale: 11 pt-ordinal scale |

Dimensions: Physical, psychological, social, and spiritual subscales evaluating QOL of thyroid cancer patients. A different version of the instrument evaluates the impact of thyroid hormone withdrawal on patients' perceived changes in QOL. Scoring: Mean scores, subscale scores, reverse anchor scoring for some items Time frame of assessment: During illness and treatment |

X | ||||||

| SNOT-22106 | 2 | X | X | X |

Items: 22 Scale: 6 pt Likert type |

Scoring: Total score range: 0–110, lower scores denote better QOL Time frame of assessment: past two weeks |

X | |||||

| University of Frankfurt QLQ48 | 1 | Not reported | Not reported |

Items: 31 (17 main) Scale: 6 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: assesses patients' beliefs, hopes and expectations, satisfaction with care, physical and psychological symptoms, relationships Time frame of assessment: past 2–3 weeks |

X | ||||||

| University of Liverpool QLQ49 | 1 | X† | Not reported |

Items: 10 Scale: Mixed format: 5 and 10 pt Likert type, yes/no |

Dimensions: communication, diet, social activity, physical functioning, appearance, emotional function, relationships, treatment regret Scoring: Total score range: 0–100 Time frame of assessment: past 4 weeks |

|||||||

| UWQOL38,39 | 142 | X | X |

Items: 12 + 3 general questions and a multiple choice item on most important issues Scale: 3, 4, 5, and 6 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: Twelve domains: pain, appearance, activity level, recreation, swallowing, chewing, speech, shoulder function, taste, saliva, depression, anxiety Scoring: Composite scores for physical function and social function (score range 0–100) and domain score Time frame of assessment: past 7 days |

F | X | X | ||||

| VHNSS107 | 1 | X | X | X |

Items: 28 Scale: 11 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: Five subscales: nutrition, pain, voice, swallow, and mucous/dry mouth Scoring: Global and subscale scores Time frame of assessment: past week |

I | |||||

Abbreviations: AQLQ, Auckland quality of life questionnaire; EORTC QLQ-H&N35, European organization for Research and treatment of Cancer questionnaire head and neck module; FACT-HN, Functional assessment of cancer therapy – head and neck module; FACT-NP, Functional assessment of cancer therapy – nasopharyngeal module; FSCI, Facial skin cancer index; FSH&N-SR, Functional status in head and neck cancer – self report measure; H&NS, Head & Neck Survey; HNC, head and neck cancer; HNCI, Head and Neck Cancer Inventory; HNQOL, University of Michigan head and neck QOL questionnaire; MDASI-HN, MD Anderson Symptom Inventory – Head and Neck; Pt, point; QOL, quality of life; QLQ, quality of life questionnaire; QOL-NPC, Quality of life for nasopharyngeal carcinoma; SNOT-22, Sinonasal outcome test – 22 item; UWQOL, University of Washington quality of life questionnaire; VHNSS, Vanderbilt head and neck symptom survey

Structure: F, Factor analysis, I, Item analysis. Unless otherwise indicated, higher scores indicate better QOL; Empty spaces indicate absence of property or lack of published information on property; Xf - face validity

Frequency counts for the general and specific EORTC instruments (QLQ-C30 and QLQ-H&N35) and FACT instruments (general, head and neck, and nasopharyngeal) were grouped together because they are often utilized together.

Cronbach's alpha for FACT-HN was low at 0.59,

U Liverpool QLQ underwent comparative validation with the FACT-HN)

Table 5.

Symptom Specific (Disfigurement) QOL measures

| Measures | Validity | Reliability | Format (Number, scale, administration options) | Interpretability | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (Of 710 studies) | Content | Criterion | Construct | Internal consistency | Test-retest | Inter-rater | Structure | Responsiveness in HNC patients | Translations | |||

| DAS2489 | 1 | X | X | X | X |

Items: 24 Scale: Likert type Options: Self |

Dimensions: general self-consciousness of appearance, sexual and bodily self-consciousness of appearance Scoring: Total score (short form), Higher scores denote more distress; Comparative norms available |

I F |

X | X | ||

| FaCE88 | 1 | X | X | X | X |

Items: 15 Scale: 5 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: Six domains: social function, facial comfort, facial movement, oral function, eye comfort, lacrimal control Scoring: Global and domain scores, transformed score range 0 to 100 Time frame of assessment: past week |

F | ||||

| NAFEQ90 | 1 | X | X | X |

Items: 14 Scale: 5 pt Likert type Options: Self and observer rated |

Dimensions: Two parts: 7 items on nasal function (airway passage, snoring, olfaction, dry mucosa, epistaxis, and phonation) and 7 items on satisfaction with nasal appearance; includes an overall assessment item in each part Scoring: Subscale scores (range 7 to 35) |

F | |||||

Abbreviations: DAS24, Derriford Appearance Scale – short form; FaCE, Facial clinimetric evaluation scale; HNC, head and neck cancer; NAFEQ, Nasal appearance and functional evaluation questionnaire; Pt, point; QOL, quality of life

Structure: F, Factor analysis, I, Item analysis. Unless otherwise indicated, higher scores indicate better QOL; Empty spaces indicate absence of property or lack of published information on property.

Site-specific (head and neck) measures

As Table 1 shows, 19 measures were identified that assess head and neck disease-related functional status and well-being. Instruments in this category were targeted towards sub-sites of head and neck tumors (e.g., nasopharyngeal and skin cancers, thyroid cancer, and parotid tumors) or HNC patients in general. QOL dimensions covered by instruments in this category varied widely and included physical function (pain, swallowing, appearance, speech, dry mouth, upper-body mobility, chewing, drooling, taste, constipation, and nutrition), psychosocial functioning, and treatment regret. Time frame of assessment ranged from “at present moment” to the “past 4 weeks.” Score transformations and global or domain scores were employed in the scoring methodology of these instruments. Of note, some of the site-specific measures were designed to stand alone, whereas others may be used in conjunction with more general, cancer-specific measures (e.g., the FACT-G and -HN, EORTC QLQ-C30 and 35 item head and neck module – QLQ-H&N35,37 and the FACT-G and nasopharyngeal module - NP).

The most frequently utilized and thoroughly tested instruments in this category were: the EORTC QLQ-H&N35 (n=244), University of Washington QOL questionnaire (UWQOL)38,39 (n=142), the FACT-HN40 (n=86), and the University of Michigan Head and Neck QOL questionnaire41 (n=27). Other less utilized but well tested instruments include the: MD Anderson Symptom Inventory Head and Neck questionnaire,42 Head and Neck Cancer Inventory,43 and the Facial Skin Cancer Index (FSCI).44,45 Four instruments lacked reported reliability or validity.46–50 Nine and 12 of the 19 instruments in this category reported on structure analysis and responsiveness, respectively. Sixteen instruments in this category have been validated and nine translated into other languages. Of note, the Parotidectomy QOL survey50 was only tested for face validity. Although, thyroid specific QOL measures are rarely encountered, the QOLThyroid instrument51 seems promising. This instrument is a modified version of a general cancer specific QOL instrument. The general instrument has been thoroughly tested for validity, reliability, and a factor analysis performed. The thyroid version was shown to be responsive with concurrent validity in patients undergoing thyroid hormone withdrawal.52 The instrument has yet to be psychometrically tested in a large sample of thyroid cancer patients.

Treatment-specific measures

As Table 2 shows, 11 measures were identified that assess the treatment-related adverse effects of radiation, chemotherapy, and surgery. Dimensions covered include physical function (digestive function, energy, sleeping, concentration, activity, recreation, appearance, pain, and site-specific physical symptoms), psychosocial function (including socioeconomic issues), and satisfaction. Time frame of assessment ranged from the “past 24 hrs” to more ambiguous timeframes such as “everyday life” and “since therapy.” The scoring methods that were employed included score ranges, MCID, and cut-off points.

Table 2.

Treatment Specific QOL measures

| Measures | Validity | Reliability | Format (Number, scale, administration option) | Interpretability | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (Of 710 studies) | Content | Criterion | Construct | Internal consistency | Test-retest | Inter-rater | Structure | Responsiveness in HNC patients | Translations | |||

| HNRT-Q56 | 10 | X | Not reported |

Items: 23 Scale: 7 pt Likert type, item 23 has 3answer options Options: Interviewer administered |

Dimensions: Six domains: oral cavity/mouth, throat, skin, digestive function, energy, psychosocial Scoring: Worst toxicity associated with lowest score, mean global score and mean domain scores Time frame of assessment: past week |

X | ||||||

| MCPLQ57 | 1 | Not reported | Not reported | Items: 48 | Not reported | |||||||

| NDI59 | 1 | Xf | X | X | X | X |

Items: 10 Scale: 6 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: Scales assessing: pain intensity, personal care, lifting, reading, headaches, concentration, work, driving, sleeping, recreation Scoring: Global score only, score range 0–50 or 0–100 %; Total score distribution: 0–4 (none), 5–14 (mild), 15–24 (moderate), 25–34 (severe), >35 (complete); MCID Time frame of assessment: everyday life |

||||

| NDII54 | 6 | X | X | X |

Items: 10 Scale: 5 pt Likert type |

Scoring: Global score, scores transformed to 0–100-point scale Time frame of assessment: past 4 weeks |

F | X | ||||

| NDQ60 | 1 | X | X | X |

Items: 12 Scale: 5 pt rating |

Dimensions: neck and shoulder symptoms, limitations in activities of daily living, occupational and leisure activities Scoring: first 7 items rated separately for each side Time frame of assessment: Since treatment |

X | |||||

| POS-HN61 | 1 | X | X | X |

Items: 6 (Pre), 9 (post) Scale: 3–5 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: psychological functioning, cosmetic appearance, satisfaction Scoring: Post-surgery questionnaire has the same 6 pre-surgery items and 3 additional questions about satisfaction; Pre-surgery: Global score (0–100) Post-surgery: Two summary scores, psychological functioning and cosmetic appearance (as in pre-surgery) and satisfaction score (0–100) Time frame of assessment: past 4 weeks |

X | |||||

| QOL-ACD91 | 1 | X | X | X |

Items: 22 Scale: 5 pt Likert type and an item using a face scale |

Dimensions: Four domains: daily activities, physical condition, social activities, mental/ psychological status Scoring: Global and subscale scores Time frame of assessment: past few days |

F | X | X | |||

| QOL-EF62 | 1 | X | X | X |

Items: 20 Scale: 5 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: physical, psychological, financial, occupational, relationship issues Scoring: Total score, score of 20 (best possible QOL) to 100 Time frame of assessment: past 7 days |

||||||

| QOL-RTI53,63 | 6 | X | X | X | X |

Items: 25 (Gen), 14 (HN) Scale: 11 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: General tool has four subscales: functional/health, emotional/psychological, family/socioeconomic, general (100 mm VAS) HN specific module: pain, appearance, speech, chewing and swallowing, mucous and saliva, taste, cough Scoring: General tool and HN module scored separately. Mean score for the general tool or the HN module Time frame of assessment: past week |

X | X | |||

| SDQ58,108 | 5 | Not reported | Not reported |

Items: 16 Scale: yes/no/not applicable |

Scoring: Summary score with range 0 (no functional limitation) to 100, Cut-off point of 18.75 balances sensitivity (74 %) and specificity (66%) Time frame of assessment: past 24 hrs |

X | X | |||||

| SPADI55 | 3 | X | X | X | X |

Items: 13 Scale: VAS (divided into 12 segments and converted into a 0–100 scale) |

Dimensions: Two scales: pain and disability Scoring: Total SPADI (mean of the two subscales) or subscale scores(expressed on a 0–100 scale), higher scores indicate greater impairment |

F | X | |||

Abbreviations: Gen, General; HN, head and neck; HNC, head and neck cancer; HNRT-Q, Head and neck radiotherapy questionnaire; MCPLQ, Mayo clinic post laryngectomy questionnaire; NDI, Neck disability index; NDII, Neck dissection impairment index; NDQ, Neck dissection quality of life questionnaire; POS-HN, Patient Outcomes of Surgery – Head/Neck; Pt, point; QOL, quality of life; QOL-ACD, QOL instrument for patients treated with anticancer drugs; QOL-EF, QOL instrument for patients with enteral feeding tubes; QOL-RTI, QOL radiation therapy index; SDQ, Shoulder disability questionnaire; SPADI, Shoulder pain and disability index; VAS, visual analogue scale

Structure: F, Factor analysis, I, Item analysis. Unless otherwise indicated, higher scores indicate better QOL; Empty spaces indicate absence of property or lack of published information on property.

Validity: Face validity denoted as Xf, HNRT-Q (reliability was interpreted as implicit but not directly measured)

The most utilized and rigorously tested instruments were the QOL radiation therapy index (QOL-RTI)53 (n=6), the Neck Dissection Impairment Index54 (n=6), and the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index55 (n=3). Three instruments lacked reliability or validity data,56–58 and a number of instruments did not provide information on structure analysis or responsiveness.59–63 Overall, there were few cross-cultural adaptations in the form of non-English translations for the instruments in this category.

HNC symptom-specific measures

Because 27 instruments were found in this category, we further divided them into subcategories for ease of presentation: xerostomia/mucositis/swallowing, voice, and disfigurement (Tables 3–5).

Table 3.

Symptom Specific (Xerostomia, mucositis, and swallowing) QOL measures

| Measures | Validity | Reliability | Format (Number, scale, administration options) | Interpretability | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (Of 710 studies) | Content | Criterion | Construct | Internal consistency | Test-Retest | Inter-rater | Structure | Responsiveness in HNC patients | Translations | |||

| EAT-1067 | 1 | X | X | X |

Items: 10 Scale: 5 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: Dysphagia Scoring: Total score, EAT-10 score of ≥ 3 is abnormal; Comparative norms available Time frame of assessment: Since onset of swallowing disorder |

X | |||||

| EDQ76 | 1 | Not reported | Not reported |

Items: 28 Scale: Mixed format: 3-answer categories (yes, no don't know), multiple answer categories |

Dimensions: Eating Habits, Personal feelings and Importance, Seeking Help Time frame of assessment: At present moment |

X | ||||||

| LORQ75 | 4 | X | X |

Items: 40 Scale: 4 pt Likert type, 6 skip items, and a free text item |

Dimensions: oral function, oro-facial appearance, social interaction, prostheses, patient denture, prosthetic satisfaction Time frame of assessment: past week |

|||||||

| MDADI64 | 23 | X | X | X | X |

Items: 20 Scale: 5 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: emotional, functional, and physical Scoring: Global score, subscale scores Time frame of assessment: past week |

X | X | |||

| OHIP-1466 | 5 | X | X |

Items: 14 Scale: 5 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: Seven: functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability, handicap Time frame of assessment: past month |

F | X | X | ||||

| OMAS68 | 2 | X | X |

Items: 3 Scale: VAS items and 4-respouse item |

Dimensions: pain and swallowing Scoring: patient and physician rated; Mean mucositis score, extent of mucositis, worst site score (maximum erythema plus maximum ulceration across all sites) Time frame of assessment: at present moment |

X | ||||||

| OMDQ69 | 1 | X | X | X | X |

Items: 12 Scale: Skip pattern, 5 pt Likert type, 11 pt linear scale multiple choice |

Dimensions: 10 questions on overall health, mouth throat soreness (MTS), 2 questions on medication use Scoring: Mean mucositis score, 0–2 = Low MTS, 3–4=high MTS group Time frame of assessment: past 24 hours |

X | ||||

| OMQOL109 | 3 | X | X | X | X |

Items: 31 Scale: 4 pt Likert type scale |

Dimensions: symptoms, diet, social function, swallowing Scoring: Total and subscale scores |

F | X | |||

| OMWQ70 | 1 | X | X | X |

Items: 12 Scale: Mixed format of 5, 7, and 11 pt Likert type scale |

Dimensions: Global health and QOL, mouth and throat soreness (MTS), mouth and throat pain Scoring: Total score, MCID range of 4–7 Time frame of assessment: past week |

X | |||||

| OPDI72,73 | 1 | X | X | X |

Items: 17 Scale: 100 mm VAS |

Dimension: Symptomatic severity of oropharyngeal dysphagia Scoring: Global score only, maximum score 1700 Time frame of assessment: At present |

F | |||||

| SSQ74 | 1 | X | X | X | X | X |

Items: 17 Scale: Mixed format: mostly 100 mm VAS, one 0–5 scale that is multiplied by 20 |

Scoring: sum scores (0–1700) (Total SSQ), General SSQ, QOL-SSQ, higher score means more severe problems Time frame of assessment: At present |

||||

| SWAL-QOL80 | 4 | X | X | X |

Items: 44 Scale: Mixed response: 5 pt Likert type, yes-no, 5-response answer categories |

Dimensions: Dysphagia-specific QOL: burden, eating duration, eating desire, symptom frequency, food selection, communication, fear, mental health, social; Generic QOL: fatigue and sleep Scoring: Scale scores Time frame of assessment: past month |

F | X | X | |||

| XeQoLS79 | 3 | Other: internal | X |

Items: 15 Scale: 5 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: physical functioning, pain/discomfort, personal/psychological, social functioning Scoring: Total and domain Time frame of assessment: past 7 days |

X | ||||||

| XI71 | 4 | X | Other: temporal stability |

Items: 11 Scale: 5 pt Likert type |

Scoring: Total score, higher scores denote greater severity of symptoms; comparative norms available Time frame of assessment: preceding 2 weeks |

X | ||||||

| XQ65 | 14 | X | X | X |

Items: 8 Scale: 11 pt ordinal Likert type |

Dimensions: Dryness while eating or chewing and dryness while not eating or chewing Scoring: Total summary score (0–100), higher scores denote worse xerostomia |

X | |||||

| XQ by Wijers et al.77 | 2 | Not reported | Not reported |

Items: 17 Scale: 4/5 grades, yes/no item, and VAS item (10 point scale) converted to 4-grade scale |

Dimensions: Assesses degree of dry mouth and xerostomia-related problems | X | ||||||

| XQ278 | 2 | Not reported | Not reported |

Items: 20 Scale: 4- 5 pt Likert type and a 100 mm VAS |

Dimensions: Xerostomia symptoms, QOL, VAS assessing xerostomia experience Scoring: summed items to get QOL score (100), and 100 mm VAS score translated into four-grade xerostomia scale |

X | ||||||

Abbreviations: EAT-10, Eating assessment tool-10 item version; EDQ, European dysphagia questionnaire; HNC, head and neck cancer; LORQ, Liverpool oral rehabilitation questionnaire; MDADI, MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory; OHIP-14, Oral health impact profile- 14 item version; OMAS, Oral mucositis assessment scale; OMDQ and OMWQ, Oral mucositis daily and weekly questionnaires; OMQOL, Oral mucositis quality of life measure; OPDI, Oral pharyngeal dysphagia inventory; Pt, point; QOL, quality of life; SSQ, Sydney swallow questionnaire; SWAL-QOL, Outcome measure of quality of life and quality of care in dysphagia patients; VAS, visual analogue scale; XeQoLS, Xerostomia-related quality of life scale; XI, Xerostomia inventory; XQ, Xerostomia questionnaire

Structure: F, Factor analysis, I, Item analysis. Unless otherwise indicated, higher scores indicate better QOL; Empty spaces indicate absence of property or lack of published information on property.

Xerostomia/mucositis/swallowing

The 17 instruments in this sub-category (Table 3) were designed to assess physical (dysphagia, eating habits, oral function, orofacial appearance, prosthetic satisfaction, pain, mucositis, xerostomia, mouth and throat soreness, fatigue, sleep, and communication) and psychosocial issues experienced by HNC patients. Time frame of assessment ranged from “at present moment” to time since the onset of a swallowing disorder. Total and subscale scores were interpreted using MCID or normative data

The most frequently utilized and tested instruments were the MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory64 (n=23), the Xerostomia Questionnaire65 (n=14), and the Oral Health Impact Profile 14-item version66 (n=5). The mucositis measures were infrequently used. Thirteen instruments in this category lacked reports on structure analysis,64,65,67–71 and four lacked responsiveness.72,73,74,75 Three measures76–78 had no evidence of validity and reliability and one had no evidence of reliability.79Only four instruments had any form of cross-cultural adaptation.64,66,76,80

Voice

The 7 instruments in this sub-category address the physical (functioning and speech or prosthesis-related issues) and psychosocial (emotional, attitudinal, environmental) impact of voice impairment and rehabilitation on QOL (Table 4). As with measures in other categories, time frame of assessment ranged from “at present moment” to “last 30 days.” Total and/or subscale or single global items scores may be interpreted using norms81,82,83,84 or cutoff points.85

Table 4.

Symptom Specific (Voice) QOL measures

| Measures | Validity | Reliability | Format (Number, scale, administration options) | Interpretability | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (Of 710 studies) | Content | Criterion | Construct | Internal consistency | Test-retest | Inter-rater | Structure | Responsiveness in HNC patients | Translations | |||

| SECEL110–112 | 3 | X | X | X | X | X |

Items: 35 Scale: 4 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: Three subscales: general, environmental, attitudinal Scoring: Total (102 pts) or scaled score, item 35 omitted in scoring Time frame of assessment: last 30 days |

F | X | X | |

| SHI86 | 2 | X | X | X | X |

Items: 31 Scale: 4 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: Two domain scores: speech, psychosocial Scoring: Total SHI (120 pts); 30 questions and single global item (answers scored 0, 30, 70, or 100) Time frame of assessment: at this moment |

X | ||||

| VASS85 | 1 | X | X | X |

Items: 5 Scale: 10 pt Likert type |

Scoring: Score of ≤5 on at least 1 of the questions indicates overall voice impairment | ||||||

| VHI and VHI-1081,82 | 46 | X | X | X |

Items: 10,30 Scale: 5 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: functional, physical, emotional Scoring: Global or subscale score: VHI-10 - global only, VHI-30 – global or subscale; comparative norms available |

I F |

X | X | |||

| VOS83 | 1 | Xf | X | X | X | X |

Items: 5 Scale: 3 and 5 pt Likert type |

Scoring: Total score; Comparative norms available | X | X | ||

| VPQ87 | 2 | X | X | X | X | X |

Items: 45 Scale: Mixed format: mostly 10-pt differential response scale, some open-ended questions Options: Self |

Dimensions: speech-related, removal-replacement related, maintenance, QOL, humidification, and hands-free issues Scoring: Differential scale; No global or overall score, questionnaire items are used to monitor and audit laryngectomees |

||||

| V-RQOL84 | 11 | X | X | X |

Items: 10 Scale: 5 pt Likert type |

Dimensions: physical functioning, social emotional Scoring: Total and domain scores, comparative data available Time frame of assessment: past two weeks |

X | |||||

Abbreviations: HNC, head and neck cancer; Pt, point; QOL, quality of life; SECEL, Self evaluation of communication experiences after laryngeal cancer; SHI, Speech handicap index; VASS, Vocal abilities and social situations questionnaire; VHI, Voice handicap index; VOS, Voice outcome survey; VPQ, Voice prosthesis questionnaire; V-RQOL, Voice-related quality of life questionnaire

Structure: F, Factor analysis, I, Item analysis. Unless otherwise indicated, higher scores indicate better QOL; Empty spaces indicate absence of property or lack of published information on property.

The most frequently utilized and tested instruments were the VHI-3081 and VHI-1081,82 (n=46). Of the remaining instruments, five were limited by structure analysis83–87 and three by responsiveness.85–87 All the instruments in this category have demonstrated reliability and validity. Majority of the instruments have existing cross-cultural adaptations.

Disfigurement

The three measures in this sub-category (Table 5) were designed to assess self-consciousness of and satisfaction with appearance, facial comfort, oral function, facial movement, snoring, and phonation. The time frame of assessment was only specified for the Facial Clinimetric Evaluation Scale (FaCE)88 – “past week.” Norms are available for the Derriford Appearance Scale (DAS24)89 to allow comparisons between studies and scores from the FaCE88 scale are converted into a transformed score for interpretability.

The instruments in this category were used infrequently amongst the 710 studies by comparison to the other categories. The most tested instrument in this category was the DAS24.89 The FaCE88 and the Nasal Appearance and Functional Evaluation Questionnaire90 were only used cross-sectionally and did not report any information regarding responsiveness over time. In addition, the latter two instruments lacked any form of cross-cultural adaptation

Discussion

Although there has been a remarkable growth in the assessment of QOL in HNC studies over the past two decades, the inconsistencies in design elements and the lack of unified reporting standards for studies testing QOL instruments, make it difficult to pool data in order to make general statements on QOL that will aid clinical decision making.

One consistently different factor among studies is the choice of QOL instrument as evidenced by the differences in frequency of use of each available instrument by clinical studies in this review. Our review found that a select few of the dozens of available instruments are used consistently by researchers across studies. To be specific, site-specific questionnaires such as the UWQOL or the EORTC QLQ-H&N35, tend to have a longer history of use since design and consequently have better reports of their properties, by comparison to instruments in other categories. In addition, although some of the site-specific instruments have been used in hundreds of studies, they do not fully address every researcher's area of interest. New instruments, like the FSCI and the QOL instrument for patients treated with anticancer drugs (QOL-ACD91), continue to emerge to address these gaps but are infrequently utilized in studies. Considering the lack of a gold-standard instrument in any one category and the continued development of QOL instruments: more research is needed to address the limitations of newer instruments, researchers need to be made aware of these instruments, and it is ever more important to have clear guidelines for selection of QOL instruments.

Our findings suggest that there is much overlap in content areas covered by the different instrument categories (e.g. fatigue, mobility, sleep, and pain). This overlap in content areas results in difficulty in selection of instruments and also in the interpretation of the clinical relevance of scores when instruments are combined. Efforts are being made to aid researchers in content comparison of QOL instruments in HNC patients. In particular, the WHO International Classification of Functioning, disability, and health (ICF) has been shown to be useful as a foundation to compare the content of QOL instruments.92 The content of some QOL instruments in the HNC population have been compared based on the ICF.93 Research in this area needs to also address the lesser utilized instruments as this would be a step towards better understanding of unique elements of the different instruments that would promote utilization and comparison. Differences in instrument properties, other than content, that are likely to affect the choice of instrument include scoring methodology and interpretability issues (e.g., time frame of assessment, availability of clinically meaningful scores and sensitivity of scoring methods), responsiveness, and respondent burden. Indeed, researchers and clinicians seeking to assess QOL in HNC patients need to consider factors such as their study objectives, instrument properties, and the pitfalls and benefits of combining measures. Each of these issues is discussed in detail below.

Study Objectives

Although there are measures targeted toward different disease populations and symptom sets, we found that some specific symptom sets (e.g., mucositis) and treatment types (e.g., laryngectomy and reconstruction) lack rigorously tested instrument options. This is particularly important because the appropriate instrument for identifying underlying mechanisms or evaluating the success of interventions varies. There is no single comprehensive instrument. However, some instruments were designed for joint assessment—that is, the core instrument can be complemented by a site-specific module to better encompass the QOL of the patient.37,40 In addition, researchers may find it helpful to use non-head and neck specific instruments to assess domains not covered by the head and neck instrument for a specific study. For instance, some head and neck specific instruments lack a psychosocial domain or certain physical sub-domains, like pain - domains that are important in the HNC population because of the prevalence and impact of depression and pain in this group of patients. Assessment of pain and psychosocial function in studies and in the clinical setting will provide a more comprehensive picture of the QOL and provides an avenue for clinical intervention. Thus, it may be necessary to use instruments specifically assessing these domains in addition to a head and neck specific instrument. Because of the aforementioned overlap among instruments, care should be taken when selecting multiple measures, not just for the purpose of reducing the respondent and administrative burden but also in anticipation of the data analysis process as discussed below. When trying to determine a cause effect relationship, the content used to assess the predictor should not overlap that used to assess QOL or the outcome QOL domain.

Instrument Properties

Instruments in this review were evaluated based on properties of sound QOL instruments as set forth by international guidelines. Although the evaluation of the quality of the properties of each instrument was by no means exhaustive, this review may provide researchers with a reference for comparing the extent and rigor of testing of the available instruments. Researchers are also presented with information that will help in recognizing the strengths of the instruments, for example: some instruments limited by lack of structural analysis may be the most ideal choice based on assessment of unique domains of interest. However, given the subjective nature of QOL, researchers should avoid utilization of instruments with no shown validity or reliability. Although several measures in each category were robust, others (e.g., the Neck Disability Index, NDI)59 require more testing or better reports of assessment. Of the instruments reviewed, 16% lacked assessment of reliability and/or validity, and this should be carefully considered when selecting instruments. In some cases, as in the assessment of xerostomia or mucositis, there may not be any rigorously tested QOL instruments, which is suggestive of the need for future research and instrument development. In other cases, researchers may have to weigh the pros and cons of different instruments based on their study design and question of interest. For example, a researcher may choose to use an instrument that lacks demonstrated responsiveness if he/she is not interested in examining changes over time.

In reviewing the measures, we elected not to assess administrative and respondent burden. Respondent burden varies with patient morbidity and functional status and is related to a greater number of items, response system (e.g., binary, Likert, or visual analogue scale), and questionnaire layout.94,95 HNC patients often have to deal with physical and psychological factors, such as fatigue and depression, that may negatively impact their ability to complete questionnaires. Only one study has sought to evaluate patient preference for number of questionnaire item and the study suggested that patients preferred questionnaires with less than 20 items.95 However, variations in question-stem length, response system, layout, and mode of delivery of questionnaire (interactive voice response systems, pen and paper, web-based modes)24 make it difficult to compare the burden of instruments. Nevertheless, it is important for researchers and clinicians to consider the instrument burden when selecting instruments and to select thoroughly tested, precise and brief instruments with administrative options.

Potential Pitfalls of Combining Measures

Most studies included in this review combined different categories of instruments to assess the QOL of patients. This combination can provide a sensitive assessment of changes in health status.27 In addition, as mentioned previously, it may be beneficial to combine head and neck-specific instruments with other symptom-specific instruments for the purpose of a comprehensive QOL assessment or to meet specific study objectives. For instance, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale96 is frequently used in head and neck studies (and was used in 76 of the 710 included studies in this review) in combination with other head and neck-specific instruments in order to assess psychological domains. At the same time, multicollinearity is a concern. Researchers should be familiar with the dimensions of and the phenomena being assessed by the instruments in their study. Scoring methodology is another issue to consider when deciding whether to combine instruments. Studies have suggested that total summary scores are not sensitive to treatment- or disease-specific changes and may be misleading if used as a measure of global QOL, because relevant facets of the patient's life may remain unaccounted for.24,97 The ability to derive subscale or domain scores is therefore an important consideration, because diverse scoring methodologies are available for the different measures.

Another issue to consider when combining measures is the time frame of assessment. We found differing time frames of assessment in measures within the same category. Short time frames may be beneficial for clinical trials by eliciting more specific reports from patients and making it easier to establish reference points for comparison.98 Combining measures that assess the same time frame simplifies the interpretation of results and is a criterion set by some cancer QOL groups for developing measures.99

Study Limitations and Strengths

One limitation of our review is that it is retrospective. We recognize that some of the instruments are relatively new and lack reports of validity testing or longitudinal use, and studies may already be under way to address these issues. Also, we did not review the quality of the validation or reliability information because this was beyond the scope of the review. The strengths of our review are that it was comprehensive, systematic, and used internationally established criteria to evaluate the QOL measures that have been used in HNC populations over the past 20 years. Although, our evaluation criteria includes the psychometric properties, information that may be available in some previous reviews, this review goes further by: assessing the instruments based on a comprehensive set of international guidelines for QOL measures and presenting information on the QOL domains, interpretability, and frequency of use of instruments – information that will aid in selection and comparison of instruments and in cross-study comparisons.

In conclusion, the impact of the diagnosis and treatment of HNC on physical and psychosocial functioning and overall well-being can not be overstated; and the research body on QOL assessment in HNC patients is growing exponentially to address the significant issue of QOL in HNC patients. It is no longer enough to assess mortality and objective morbidity when evaluating treatment alternatives. The patient's QOL is important in the assessment of survival because the goal of optimal patient care is to prolong life not to delay death at the expense of physical and psychosocial suffering. However, the science of QOL assessment has yet to merge with its clinical application.

One of the problems impeding clinical translation is the lack of familiarity with properties of available measures in order to compare and contrast measures and make informed decisions on which measure is best suited to specific research or patient-care objectives. By presenting a comprehensive, systematic review of existing QOL measures, specific to the head and neck population, and their properties, this review represents a necessary first step toward improving QOL assessment by facilitating informed selection of instruments. Ultimately, this would serve as a platform for the development of standardized guidelines for selection of instruments and integrating QOL assessment in clinical settings. An interesting initiative to facilitate comparison of QOL data across studies is the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Initiative (PROMIS).100 This National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute backed initiative aims to create a database of psychometrically tested item banks, covering specific health domains, for assessment of patient-reported outcomes including QOL that will be publicly available.101 Although the potential impact of this project in the field of general and broadly cancer-specific QOL assessment is exciting, the issue of lack of important head and neck cancer-specific domains (e.g. speech, dysphagia, oral pain) stands to pose a problem for the assimilation of the PROMIS items in head and neck cancer trials. Given the wide utilization of several instruments in the head and neck literature, efforts (like the WHO ICF content comparison or perhaps, a QOL practice algorithm for selection of instruments) are needed to enable cohesive interpretation and comparison of data from studies utilizing the myriad of measures. The use of clinically meaningful benchmarks, such as MCID, normative data, and other clinical anchors, is emerging in the field of QOL and will facilitate translation of these measures into the clinical setting. In addition, in order to make clinically meaningful QOL instrument comparisons, more RCTs evaluating treatment alternatives using rigorously tested instruments are needed. This would facilitate adoption of such instruments in the clinical setting for patients undergoing specific treatments. In addition, a more systematic approach to selecting rigorously tested instruments is necessary that takes into account differences in study objectives (population, intervention, or symptom), study design (prospective or cross-sectional), content/QOL domains, the need for a supplementary QOL instrument, and the time frame of assessment of the questionnaire. A systematic approach that takes these factors into consideration is critical towards translating the research progress of QOL assessment in HNC patients into the clinical scene.

Acknowledgments

Role of the Funding Source This work was supported in part by a career development grant [K07CA124668] from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health awarded to [H.B.]. This funding organization did not play any role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts and Figures. Atlanta, GA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers SN, Ahad SA, Murphy AP. A structured review and theme analysis of papers published on 'quality of life' in head and neck cancer: 2000–2005. Oral Oncol. 2007;43:843–868. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy BA, Ridner S, Wells N, Dietrich M. Quality of life research in head and neck cancer: A review of the current state of the science. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;62:251–267. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breitbart W, Holland J. Psychosocial aspects of head and neck cancer. Semin Oncol. 1988;15:61–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gritz ER, Carmack CL, deMoor C, et al. First year after head and neck cancer: quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:352–360. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keefe FJ, Brantley A, Manuel G, Crisson JE. Behavioral assessment of head and neck cancer pain. Pain. 1985;23:327–336. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keefe FJ, Wilkins RH, Cook WA. Depression, pain, and pain behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54:665–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.List MA, Ritter-Sterr C, Lansky SB. A performance status scale for head and neck cancer patients. Cancer. 1990;66:564–569. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900801)66:3<564::aid-cncr2820660326>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.List MA, Stracks J. Evaluation of quality of life in patients definitively treated for squamous carcinoma of the head and neck. Curr Opin Oncol. 2000;12:215–220. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200005000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LoTempio MM, Wang KH, Sadeghi A, Delacure MD, Juillard GF, Wang MB. Comparison of quality of life outcomes in laryngeal cancer patients following chemoradiation vs. total laryngectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132:948–953. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duke RL, Campbell BH, Indresano AT, et al. Dental status and quality of life in long-term head and neck cancer survivors. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:678–683. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000161354.28073.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morton R, Davies D, Baker J, Baker G, Stell P. Quality of life in treated head and neck cancer patients: a preliminary report. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1984;9:181–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1984.tb01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zabora J, Brintzenhofeszoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psycho Oncology. 2001;10:19–28. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::aid-pon501>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiu N, Sun T, Wu C, Leung S, Wang C, Wen J. Clinical characteristics of outpatients at a psycho-oncology clinic in a radiation oncology department. Chang Gung Med J. 2001;24:181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Misono S, Weiss NS, Fann JR, Redman M, Yueh B. Incidence of suicide in persons with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4731. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.8941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krouse JH, Krouse HJ, Fabian RL. Adaptation to surgery for head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:789–794. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198908000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dropkin MJ. Coping with disfigurement and dysfunction after head and neck cancer surgery: a conceptual framework. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1989;5:213–219. doi: 10.1016/0749-2081(89)90095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howren MB, Christensen AJ, Karnell LH, Funk GF. Health-related quality of life in head and neck cancer survivors: impact of pretreatment depressive symptoms. Health Psychol. 2010;29:65–71. doi: 10.1037/a0017788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer F, Fortin A, Gelinas M, et al. Health-related quality of life as a survival predictor for patients with localized head and neck cancer treated with radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2970–2976. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Ronis DL, Fowler KE, Terrell JE, Gruber SB, Duffy SA. Quality of life scores predict survival among patients with head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2754–2760. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.9510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scharpf J, Karnell LH, Christensen AJ, Funk GF. The role of pain in head and neck cancer recurrence and survivorship. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:789–794. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Induction Chemotherapy plus Radiation Compared with Surgery plus Radiation in Patients with Advanced Laryngeal Cancer. The Department of Veterans Affairs Laryngeal Cancer Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1685–1690. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106133242402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terrell JE, Fisher SG, Wolf GT. Long-term quality of life after treatment of laryngeal cancer. The Veterans Affairs Laryngeal Cancer Study Group. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:964–971. doi: 10.1001/archotol.124.9.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trask P, Hsu M, McQuellon R. Other paradigms: health-related quality of life as a measure in cancer treatment: its importance and relevance. Cancer J. 2009;15:435. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181b9c5b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gotay CC, Moore TD. Assessing quality of life in head and neck cancer. Qual Life Res. 1992;1:5–17. doi: 10.1007/BF00435431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ringash J, Bezjak A. A structured review of quality of life instruments for head and neck cancer patients. Head Neck. 2001;23:201–213. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200103)23:3<201::aid-hed1019>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pusic A, Liu JC, Chen CM, et al. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures in head and neck cancer surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136:525–535. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patient-Reported Outcome and Quality of Life Instruments Database. MAPI Research Trust. 2011 http://www.proqolid.org/

- 29.Lohr KN. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: Attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:193–205. doi: 10.1023/a:1015291021312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sayed SI, Elmiyeh B, Rhys-Evans P, et al. Quality of life and outcomes research in head and neck cancer: a review of the state of the discipline and likely future directions. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:397–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terwee CB, Bot SDM, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Efficace F, Bottomley A, Osoba D, et al. Beyond the development of health-related quality-of-life (HRQOL) Measures: A checklist for evaluating HRQOL outcomes in cancer clinical trials--does HRQOL evaluation in prostate cancer research inform clinical decision making? J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3502. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kimberlin CL, Winterstein AG. Validity and reliability of measurement instruments used in research. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65:2276. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group tP. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas J, Brunton J, Graziosi S. EPPI-Centre Software. Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education; London: 2010. EPPI-Reviewer 4.0: software for research synthesis. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19:539–549. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bjordal K, Hammerlid E, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, et al. Quality of life in head and neck cancer patients: validation of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-H&N35. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1008–1019. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hassan SJ, Weymuller EA., Jr. Assessment of quality of life in head and neck cancer patients. Head Neck. 1993;15:485–496. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880150603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weymuller EA, Jr., Alsarraf R, Yueh B, Deleyiannis FW, Coltrera MD. Analysis of the performance characteristics of the University of Washington Quality of Life instrument and its modification (UW-QOL-R) Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:489–493. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.5.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.List MA, Dantonio LL, Cella DF, et al. The performance status scale for head and neck cancer patients and the functional assessment of cancer therapy head and neck scale - A study of utility and validity. Cancer. 1996;77:2294–2301. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960601)77:11<2294::AID-CNCR17>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terrell JE, Nanavati KA, Esclamado RM, Bishop JK, Bradford CR, Wolf GT. Head and neck cancer-specific quality of life: instrument validation. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:1125–1132. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1997.01900100101014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenthal DI, Mendoza TR, Chambers MS, et al. Measuring head and neck cancer symptom burden: the development and validation of the M. D. Anderson symptom inventory, head and neck module. Head Neck. 2007;29:923–931. doi: 10.1002/hed.20602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Funk GF, Karnell LH, Christensen AJ, Moran PJ, Ricks J. Comprehensive head and neck oncology health status assessment. Head Neck. 2003;25:561–575. doi: 10.1002/hed.10245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rhee JS, Matthews BA, Neuburg M, Logan BR, Burzynski M, Nattinger AB. Validation of a quality-of-life instrument for patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2006;8:314–318. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.8.5.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rhee JS, Matthews BA, Neuburg M, Logan BR, Burzynski M, Nattinger AB. The skin cancer index: clinical responsiveness and predictors of quality of life. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:399–405. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31802e2d88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rathmell AJ, Ash DV, Howes M, Nicholls J. Assessing quality of life in patients treated for advanced head and neck cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 1991;3:10–16. doi: 10.1016/s0936-6555(05)81034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gu MF, Du YZ, Chen XL, Li JJ, Zhang HM, Tong Q. Item selection in the development of quality of life scale for nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Ai Zheng. 2009;28:82–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Becker G, Momm F, Xander C, et al. Religious belief as a coping strategy: an explorative trial in patients irradiated for head-and-neck cancer. Strahlenther Onkol. 2006;182:270–276. doi: 10.1007/s00066-006-1533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Young PE, Beasley NJ, Houghton DJ, et al. A new short practical quality of life questionnaire for use in head and neck oncology outpatient clinics. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1998;23:528–532. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1998.2360528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patel N, Har-El G, Rosenfeld R. Quality of life after great auricular nerve sacrifice during parotidectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:884–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ferrell BR, Grant, Dow Hassey. Quality of Life - Thyroid Version. [Accessed 11/29/2010];City of Hope Pain & Palliative Care Resource Center. 2000 http://prc.coh.org/pdf/Thyroid%20QOL.pdf.

- 52.Dow KH, Ferrell BR, Anello C. Quality-of-life changes in patients with thyroid cancer after withdrawal of thyroid hormone therapy. Thyroid. 1997;7:613–619. doi: 10.1089/thy.1997.7.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trotti A, Johnson DJ, Gwede C, et al. Development of a head and neck companion module for the quality of life-radiation therapy instrument (QOL-RTI) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42:257–261. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taylor RJ, Chepeha JC, Teknos TN, et al. Development and validation of the neck dissection impairment index: a quality of life measure. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:44–49. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roach K, Budiman-Mak E, Songsiridej N, Lertratanakul Y. Development of a shoulder pain and disability index. Arthritis Care Res. 1991;4:143–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Browman GP, Levine MN, Hodson DI, et al. The Head and Neck Radiotherapy Questionnaire: a morbidity/quality-of-life instrument for clinical trials of radiation therapy in locally advanced head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:863–872. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.5.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.DeSanto LW, Olsen KD, Perry WC, Rohe DE, Keith RL. Quality of life after surgical treatment of cancer of the larynx. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1995;104:763–769. doi: 10.1177/000348949510401003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van der Heijden G, Leffers P, Bouter L. Shoulder disability questionnaire design and responsiveness of a functional status measure. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vernon H, Mior S. The Neck Disability Index: a study of reliability and validity. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1991;14:409–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Inoue H, Nibu K, Saito M, et al. Quality of life after neck dissection. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:662–666. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.6.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cano SJ, Browne JP, Lamping DL, Roberts AH, McGrouther DA, Black NA. The Patient Outcomes of Surgery-Head/Neck (POS-head/neck): a new patient-based outcome measure. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stevens CS, Lemon B, Lockwood GA, Waldron JN, Bezjak A, Ringash J. The development and validation of a quality-of-life questionnaire for head and neck cancer patients with enteral feeding tubes: the QOL-EF. Support Care Cancer. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0934-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Johnson D, Casey L, Noriega B. A pilot study of patient quality of life during radiation therapy treatment. Qual Life Res. 1994;3:267–272. doi: 10.1007/BF00434900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen AY, Frankowski R, Bishop-Leone J, et al. The development and validation of a dysphagia-specific quality-of-life questionnaire for patients with head and neck cancer: the M. D. Anderson dysphagia inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:870–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eisbruch A, Kim HM, Terrell JE, Marsh LH, Dawson LA, Ship JA. Xerostomia and its predictors following parotid-sparing irradiation of head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:695–704. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01512-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Slade G. Derivation and validation of a short form oral health impact profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25:284–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Belafsky PC, Mouadeb DA, Rees CJ, et al. Validity and reliability of the Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10) Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117:919–924. doi: 10.1177/000348940811701210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sonis S, Eilers J, Epstein J, et al. Validation of a new scoring system for the assessment of clinical trial research of oral mucositis induced by radiation or chemotherapy. Cancer. 1999;85:2103–2113. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990515)85:10<2103::aid-cncr2>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stiff P, Erder H, Bensinger W, et al. Reliability and validity of a patient self-administered daily questionnaire to assess impact of oral mucositis (OM) on pain and daily functioning in patients undergoing autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37:393–401. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Epstein JB, Beaumont JL, Gwede CK, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of the oral mucositis weekly questionnaire-head and neck cancer, a patient-reported outcomes questionnaire. Cancer. 2007;109:1914–1922. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thomson W, Williams S. Further testing of the xerostomia inventory. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:46–50. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(00)80013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wallace K, Middleton S, Cook I. Development and validation of a self-report symptom inventory to assess the severity of oral-pharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:678–687. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Garcia-Peris P, Paron L, Velasco C, et al. Long-term prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients: Impact on quality of life. Clin Nutr. 2007;26:710–717. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dwivedi RC, St Rose S, Roe JW, et al. Validation of the Sydney Swallow Questionnaire (SSQ) in a cohort of head and neck cancer patients. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:e10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]