Abstract

Asthma is an important health problem worldwide and the prevalence is increasing in most part of the world. The burden of this disease to governments, health-care systems, and patients and their families have been greater more than ever despite efforts advocated by Global Initiative for Asthma for total asthma controls. Using Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, in this review, the population-based prospective studies showed the costs and health care utilization of childhood asthma in Taiwan was 2 folds higher than non-asthmatic children, and the prescription patterns of anti-asthmatic medications among physician in different discipline were all far from satisfied. The appropriateness of combinational therapy of inhaled corticosteroids and long acting β-agonists for moderate to severe childhood asthma was only 62%. In a government-sponsored disease management program for asthmatic patients within national health insurance, though the total mean costs (26.5%) and outpatient costs (26.1%) increased, the mean emergency department visits and hospitalization rates were significantly reduced by 34.4% and 51.74%, respectively, compared to the previous year. Therefore, in the real-world situation, asthmatic patients as well as medical professions who take care of asthmatic children still have much space for their symptoms controls and knowledge improvement to reduce the burden of asthma. From the experience of care and management of childhood asthma in Taiwan may reveal same problems of childhood asthma care in the similar cultural and ecological environments of Asian pacific countries, and suggest government-sponsored program may also have significant impact aimed at improving the care of patients with asthma.

Keywords: Childhood asthma, Health care utilization, Disease management, National health insurance

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is an important health problem worldwide and the prevalence is increasing in most part of the world [1, 2]. The burden of this disease to governments, health-care systems, and patients and their families has been greater more than ever. In Taiwan, the prevalence of asthma increased from 5.8 to 12.7% between 1985 and 1995 [3, 4]. These data revealed more than tenfold increase in the prevalence of asthma in school children in Taiwan from 1974 to 1995, but virtually no change in the decade from 1995 to 2005. Maintenance medications and other controller therapies allow many patients to control their asthma, but the cost of treatment can be high. In addition, the treatment of acute attacks and comorbidities of asthma consumes considerable medical resources. As a leading chronic childhood illness in the developed countries, asthma places a large burden on affected children and their families. According to Health and Vital Statistics Republic of China [5], asthma mortality in Taiwan has decreased from 8.17 per 100,000 in 1981 to 4.5 in 2000, but the mortality rate in Taiwan is still greater than that in the USA (1.6 per 100,000) [6]. Although asthma is a major cause of childhood disability [7, 8] and in rare cases causes premature death, asthma morbidity and mortality are largely preventable when patients and their families are adequately educated about the disease and have access to high-quality health care [9, 10]. That is, poor outcomes for childhood asthma, such as hospitalizations and deaths, are at least partially sensitive to the quality of ambulatory health care [11]. Thus, it is important to simultaneously monitor trends in asthma prevalence, health care utilization, and mortality to estimate the burden of disease and to help assess the impact of asthma prevention programs and changes in health care quality. It is imperative to know the medical costs and health care utilization of childhood asthma using a population-based analysis, to gain the insight of real world situation for asthma treatments and controls in general population as well as in health care providers [12, 13]. Although local data may be optimal for program evaluation and resource allocation decisions, national data are presented in analysis because population-based data for the entire spectrum of measures may consistently available in the other areas with same ecological and cultural background. Therefore this review will summarized the reports conducted by using Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) for an overall understanding of the health care costs and utilization for children with asthma. We think the experience in Taiwan may serve as an example on how to care and focus in different aspects of childhood asthma control in this region of Asian pacific countries.

NHIRD

Since March 1, 1995, when Taiwan implemented universal national health insurance (NHI) legislation, coverage has increased from 57% to 98% of the population [14]. The Bureau of National Health Insurance is the sole buyer of health services and regulates payments for medical care, which added coverage for children, elderly persons, and nonworking adults. In addition, copayments (10% for inpatient and 20% for outpatient care) were waived for the very poor, veterans, and aborigines. Since then, the NHI reimbursement claims data have been managed by the National Health Research Institutes (NHRI) in Taiwan and established the NHIRD, a medical claim database (including inpatient and outpatient services) has released for research purposes. Specifically, the NHIRD provide a large population-based and valuable source for epidemiology studies. Complete data including enrollment data, hospitalization data, inpatient drug exposure data, and outpatient diagnosis data are maintained by the NHI research databases. Therefore, this database is also suitable for cohort studies and case-control studies as well as offers a good opportunity for a population-based study [15].

Health care utilization and costs of asthma in Taiwan

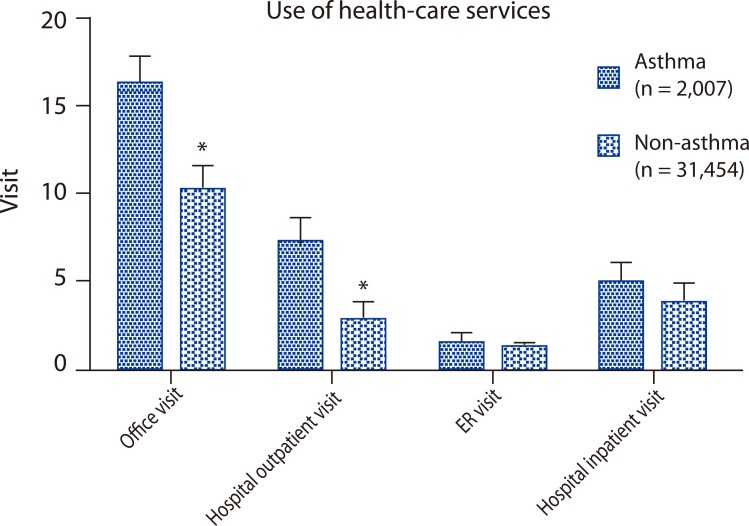

From 1985 to 1994, the estimated total cost of illness for pediatric (younger than 17 years) asthma increased from $2.25 billion (in 1994 dollars) to $3.17 billion despite a 15.5% decrease in the cost of care per child [16]. There are two types of costs contributing to the total cost of an illness, i.e, direct and indirect costs. Direct costs include both medical and non-medical expenses associated with the disease. Medical direct costs include those expenses generated in the disease's prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation. Non-medical direct costs include transportation to and from the health provider and purchase of home health care. Indirect costs include days missed from work, school days lost (caretaker needs to refrain from usual daily activities to care for the child), and loss of future potential earnings as a result of premature death [17]. To investigate total health-care costs for pediatric patients with asthma in Taiwan, Sun et al. [18] have enrolled data of 33,461 patients aged 3-17 years in the NHIRD from 1 January to 31 December 2002. Health-care utilization and costs, including those related to office, outpatient hospital, emergency department, and inpatient hospital visits were compared between pediatric patients with and without asthma. Their findings revealed that in 2002, the period prevalence of treated asthma was 6.0%. Pediatric patients with asthma used substantially more health services than did those without asthma in all categories. Hospital outpatient visits and overall health-care expenditure for patients with asthma were 2.2-fold higher than those of patients without asthma (Fig. 1). Almost three-fourths of all asthma-related costs were attributable to office and hospital outpatient visits; one-fourth was attributable to urgent care and hospitalizations. In detail, total direct medical expenditure is approximately $NTD 275 million (approximately $US 8.3 million) per year in this 1% (33,461) sample of general population enrollees aged 3-17 years in Taiwan. Asthma care accounted for 20-25% of all services that patients with asthma received. Therefore, patients with asthma incurred costs of approximately $NTD 7.1 billion ($US 215 million). In 2002, the exchange rate was $NTD 33.1 to $US 1. The cost observed ($US 83 per asthmatic children per year) was far lower than those of other national surveys from Thailand ($US 216 in the year 2007) [19], Singapore ($US 238 in the year 1999) [20], and the USA ($US 333 in the year 1994) [21]. The difference may have reflected our provider payments (approximately $US 10 per case), patient copayments (approximately $US 3-8 per visit), and laboratory and radiology fees, which are lower than those of other countries. However, asthma care still imposes a large economic burden on patients' family in Taiwan. In another study, Sun and Lue [22] evaluated 95,110 patient aged 18-55 years who were enrolled in the NHIRD in the same year of 2002, have also found the mean costs of hospitalization for patients with asthma were 2.7-fold higher than those of patients without asthma, and almost one-half of all asthma-related costs were attributable to hospitalization.

Fig. 1.

Health care utilization and medical costs by asthmatic and non-asthmatic children (data modified from Sun et al. [18]). *p < 0.05 (paired Student's t test), as compared to the non-asthmatic children.

Prescription patterns and appropriateness of anti-asthmatic medications for children among physicians with different disciplines

Although in 1998, a learning program for physicians named the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) program was begun in an effort to raise awareness among health care workers and the general public about the increasing rates of asthma and the need for standardized asthma care [23], there was no consensus in defining optimal medical care for asthma emerges from the knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and actual practice patterns of medical care specialists in the year 2002 (The diagnosis and treatment guideline of childhood asthma in Taiwan was published in 2008). According to GINA guidelines, several drugs are recommended either alone or in combination to treat asthma, including β2-agonists (oral or inhaled form), corticosteroids (oral or inhaled form), xanthine derivatives, and leukotriene receptor antagonists. Due to cultural differences, an inefficient and poorly functioning referral system, and comparatively convenient access to health care provided by the NHI program in Taiwan, asthma care in children is provided by a wider array of medical practitioners, including general pediatricians, family physicians and other physicians, such as those specializing in internal medicine. Sun et al. [24] have used the NHIRD in the year 2002 to evaluate the differences in the quality of care and care preferences for asthmatic children provided by pediatricians, family physicians and other practitioners. Data for a total of 225,537 anti-asthma prescriptions were collected from the NHRI Database from January 1, 2002 to March 31, 2002. Medications included inhaled and oral adrenergics, inhaled and oral corticosteroids, xanthine derivatives, and leukotriene receptor antagonists prescribed by general pediatricians, family physicians and physicians in other disciplines. Oral β2-agonist was the most commonly prescribed drug used as monotherapy by pediatricians (70.4%), family physicians (46.9%) and other physicians (50.8%), respectively. The prescription rate for inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) monotherapy was surprising low, for 7.8% by pediatricians, 5.6% by family physicians, and 8.0% by other physicians. In contrast, the prescription rate for inhaled adrenergic (short acting β2-agonist) was the highest in family physicians (14.9%), followed by the other physicians (7.2%), and was lowest in pediatricians (3.1%). Lozano et al found that the most common asthma medication regimens used by children with asthma in the USA were oral β2-agonist (15.4%), β2-agonist plus theophylline (10.4%), theophylline (6.1%) and β2-agonist plus corticosteroid (2.7%) [25]. Thus, oral β2-agonist, theophylline and oral corticosteroid are the most commonly prescribed drugs in both Taiwan and abroad. GINA guidelines emphasize the use of inhaled anti-inflammatory agents, particularly corticosteroid. In Sun's study [24], family physicians demonstrated the lowest prescription rate of inhaled corticosteroid (5.6%). This rate is lower than in studies from other countries. In contrast, oral forms of therapy are easier for patients to use and do not require physicians to spend additional time as would be required to demonstrate how to use inhaled preparations. This convenience may be one of the factors responsible for the high rate of prescription of oral β2-agonists. Another important issue is that, in Taiwan, many parents are concerned about the side effects of inhaled corticosteroids that are to be used as controller medications for at least 3 months. Such concerns may affect a physician's intention to prescribe inhaled corticosteroid. In addition, the quality of the interaction between physicians, parents and children affects treatment efficiency. Therefore, the discrepancy between the ideal of asthma controls recommended by GINA guideline and the reality in the prescription and practice of physicians for childhood asthma was huge in 2002.

Appropriate use of combination therapy (inhaled corticosteroid plus long acting beta 2 adrenergic agonist) in asthma children

According to National Institutes of Health and GINA guidelines, the preferred long-term control medications for persistent asthma are ICSs. Addition of a long acting beta 2-adrenergic agonist (LABA) to an ICS is the preferred treatment option for patients with moderate or severe persistent asthma not adequately controlled on previous medications, with high impairment, or at high risk for an asthma exacerbation. Results from retrospective claims-based studies in the U.S. and Canada showed that less than 40% of patients started on ICS/LABA therapy had evidence of previous ICS use, in other words, ICS/LABA combination therapy was not used in accordance with guidelines in more than 60% of patients [26, 27]. Sun's study [24] found that combined treatment using both ICS and LABA was prescribed at <1% of outpatient visits in all three physician groups. This may be due to the lack of familiarity with newer treatment concepts or underestimation of asthma severity in pediatric patients. But the information about the appropriate use with ICS/LABA is unavailable in Taiwan. From our unpublished study that investigate sample population included pediatric patients (<18 year-old, n = 6,500) who initiated fluticasone/salmeterol or budesonide/formoterol combination therapy in the Data from 2007 NHIRD (January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2007). Use was considered appropriate if patients met any of the criteria during a 1-year period before ICS/LABA initiation, i.e. according to GINA guideline with previous ICS used; or according to clinical needs, such as previous SABA used (>once per day), > 1 pharmacy claim for oral corticosteroid used for asthma attack, ER visit due to asthma (oral corticosteroid used), and admission due to asthma. Factors associated with appropriate initiation of ICS/LABA therapy were also assessed. The results showed that ICS/LABA combination therapies are being prescribed appropriately in 62.39% of study population, and 37.61% of patients started on ICS/LABA therapy had no evidence of previous ICS use and moderate to severe asthma. With respect to the appropriate group, "≥1 pharmacy claim for oral steroids (OCs)" (55.4%), c≥1 pharmacy claim for OCs with asthmal and ICS (17.9%) are the most frequent indicators, respectively. As for the inappropriate group, sustained-release theopylline and leukotriene receptor antagonist were the most frequent monotherapy. Results from our study revealed that ICS/LABA therapy was prescribed earlier, and only 60% of ICS/LABA prescribing was consistent with GINA or NAEPP asthma guidelines.

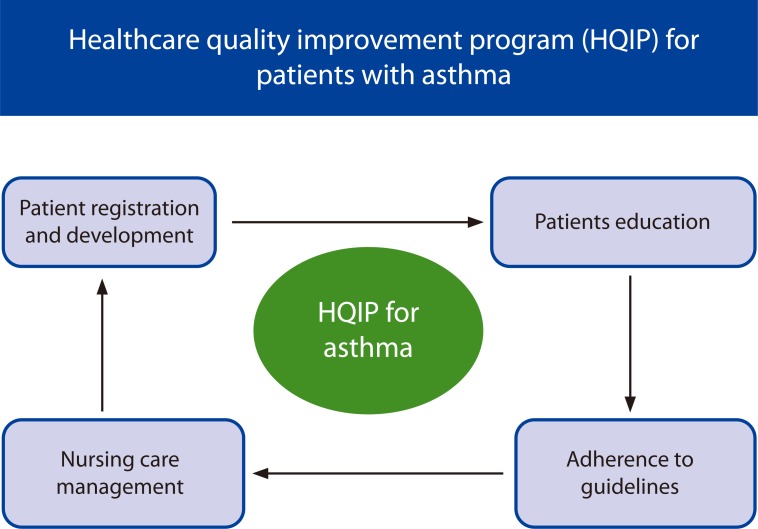

Healthcare quality improvement program (HQIP) for patients with asthma

According to the Department of Health, Republic of China executives, the pharmaceutics cost related to asthma was estimated at 673 million NT dollars in 1994, and increased by 84% up to 1,224 million NT dollars in 1998. These results conclusively demonstrated that asthma control in Taiwan fell markedly short of goals specified in the GINA guideline, as evidences showed above. In response to the increasing cost, increasing prevalence rates and comparatively higher mortality of asthma, the Bureau of National Health Insurance (BNHI) in Taiwan [14] initiated a HQIP for patients with asthma in November 2001. The primary objectives of the HQIP were to (i) improve patients' self-management practices; (ii) improve clinical outcomes and quality of care; (iii) reduce treatment cost related to asthma; (iv) increase patient and physician satisfaction with continuity of care; and (v) promote adherence to practice guidelines and appropriate therapeutic recommendations to providers. The HQIP was a 1-year package of interventions, financed with a fixed percentage of the insurance premium [28]. If complication rates were lowered by the program, the lower use and associated saving could result in extra reimbursement from the BNHI to the health care providers. Features of the program were registry development, adherence to guidelines, patient education and nursing care management (Fig. 2). For patients with asthma, health care providers had to complete a 6-h BNHI-sponsored asthma skills training session to be certified and to begin to recruit patients. In providing holistic care for the patients with asthma, the asthma nurse played the role of case manager, leading patients and coordinating collective care for patients. The primary care physician retained accountability for making the initial diagnosis and ensuring overall continuity of care. The program was implemented in the following phases: (i) patient identification and registry process; (ii) care manager intervention; and (iii) regular follow-ups, as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The notion of government-sponsored disease management program for asthmatic patients in the Taiwan National Health Insurance.

After one year of implementation, the preliminary report on the impact of this government sponsored outpatient-based diseases management for people with asthma on the economic outcome, the physician's and the patient's satisfaction was reported by Weng' s study [28, 29]. The specific objectives of the study were to analyze and compare medical resource utilization associated with asthma treatment before and after a 1-year implementation of the HQIP in pediatric patients with asthma, and to investigate the children's and their parents' satisfaction with the care provided by HQIP. There were 854 patients completed 1-year follow-up program and responded to questionnaire (27.7%). Although the total mean costs (26.5%) and outpatient costs (26.1%) increased, the mean emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalization rates were significantly reduced by 34.4% and 51.74%, respectively, compared to the previous year. These findings would be expected if outcome-based disease management were effectively promoting clinically indicated outpatient interventions, thereby avoiding complications that resulted in inpatient admissions and ED utilization as well as higher costs. A majority of physicians (70-85%) had positive opinions toward the HQIP. More than 80% of the patients showed positive feedback to the HQIP. The majority of the patients substantially adhered to physicians' suggestions, and had more accurate knowledge and better self-care skills concerning asthma. These results have significance for the design of future programs aimed at improving the care of patients with asthma in NHI, Taiwan.

CONCLUSION

The burden of asthma, particularly in children, have been greater more than ever to patients and their families as well as to governments and health-care systems despite efforts advocated by GINA for total asthma controls. Using Taiwan NHIRD, the population-based prospective studies showed the costs and health care utilization, the prescription patterns of anti-asthmatic medications among physician in different discipline, the appropriateness of combinational therapy of ICS and LABA for moderate to severe childhood asthma were far from satisfaction. Therefore, in the real-world situation, asthmatic patients as well as medical professions who take care of asthmatic children still have much space for their symptoms controls and knowledge improvement to reduce the burden of asthma. From the experience of care and management of childhood asthma in Taiwan, it may reveal same problems of childhood asthma care in the similar cultural and ecological environments of Asian pacific countries, and suggest government-sponsored program may also have significant impact aimed at improving the care of patients with asthma.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank the data and published reports provided by the Taiwan Academic of Pediatric Allergy, Asthma and Clinical Immunology.

References

- 1.Pearce N, Aït-Khaled N, Beasley R, Mallol J, Keil U, Mitchell E, Robertson C. Worldwide trends in the prevalence of asthma symptoms: phase III of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Thorax. 2007;62:758–766. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.070169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, Lai CK, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, Williams H. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006;368:733–743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsieh KH, Shen JJ. Prevalence of childhood asthma in Taipei, Taiwan, and other Asian Pacific countries. J Asthma. 1988;25:73–82. doi: 10.3109/02770908809071357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu WF, Wan KS, Wang SJ, Yang W, Liu WL. Prevalence, severity, and time trends of allergic conditions in 6-to-7-year-old schoolchildren in Taipei. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2011;21:556–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health. Health and vital statistics Republic of China, 1981-2002. Taipei: Department of Health; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/asthma.htm.

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disabilities among children aged less than or equal to 17 years -- United States, 1991-1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44:609–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newacheck PW, Budetti PP, Halfon N. Trends in activity-limiting chronic conditions among children. Am J Public Health. 1986;76:178–184. doi: 10.2105/ajph.76.2.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Homer CJ, Szilagyi P, Rodewald L, Bloom SR, Greenspan P, Yazdgerdi S, Leventhal JM, Finkelstein D, Perrin JM. Does quality of care affect rates of hospitalization for childhood asthma? Pediatrics. 1996;98:18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program: Expert Panel Report 2. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Bethesda: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sly RM. Decreases in asthma mortality in the United States. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:121–127. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newacheck PW, Halfon N. Prevalence, impact, and trends in childhood disability due to asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:287–293. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akinbami LJ, Schoendorf KC. Trends in childhood asthma: prevalence, health care utilization, and mortality. Pediatrics. 2002;110:315–322. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.2.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bureau of National Health Insurance. National Health Insurance Annual Statistical Report. Taipei: Bureau of National Health Insurance; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsiao FY, Yang CL, Huang YT, Huang WF. Using Taiwan's National Health Insurance Research Databases for pharmacoepidemiology research. J Food Drug Anal. 2007;15:99–108. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss KB, Sullivan SD, Lyttle CS. Trends in the cost of illness for asthma in the United States, 1985-1994. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106:493–499. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.109426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gergen PJ. Understanding the economic burden of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:S445–S448. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.114992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun HL, Kao YH, Lu TH, Chou MC, Lue KH. Health-care utilization and costs in Taiwanese pediatric patients with asthma. Pediatr Int. 2007;49:48–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2007.02317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gypmantasiri S. Costs of illness of asthma in Chiang Mai and Lumphun. Chiang Mai Univ J Econ. 2007;11:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chew FT, Goh DY, Lee BW. The economic cost of asthma in Singapore. Aust N Z J Med. 1999;29:228–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1999.tb00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mellon M, Parasuraman B. Pediatric asthma: improving management to reduce cost of care. J Manag Care Pharm. 2004;10:130–141. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2004.10.2.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun HL, Lue KH. Health care utilization and costs of adult asthma in Taiwan. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2008;29:177–181. doi: 10.2500/aap.2008.29.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Global Initiative for Asthma. NHLBI/WHO workshop report: global strategy for asthma management and prevention (revised 2009) Available from: http://www.ginasthma.com.

- 24.Sun HL, Kao YH, Chou MC, Lu TH, Lue KH. Differences in the prescription patterns of anti-asthmatic medications for children by pediatricians, family physicians and physicians of other specialties. J Formos Med Assoc. 2006;105:277–283. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lozano P, Sullivan SD, Smith DH, Weiss KB. The economic burden of asthma in US children: estimates from the National Medical Expenditure Survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:957–963. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shrewsbury S, Pyke S, Britton M. Meta-analysis of increased dose of inhaled steroid or addition of salmeterol in symptomatic asthma (MIASMA) BMJ. 2000;320:1368–1373. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7246.1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazarus SC, Boushey HA, Fahy JV, Chinchilli VM, Lemanske RF, Jr, Sorkness CA, Kraft M, Fish JE, Peters SP, Craig T, Drazen JM, Ford JG, Israel E, Martin RJ, Mauger EA, Nachman SA, Spahn JD, Szefler SJ. Long-acting beta2-agonist monotherapy vs continued therapy with inhaled corticosteroids in patients with persistent asthma: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:2583–2593. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.20.2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weng HC. Impacts of a government-sponsored outpatient-based disease management program for patients with asthma: a preliminary analysis of national data from Taiwan. Dis Manag. 2005;8:48–58. doi: 10.1089/dis.2005.8.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weng HC, Yuan BC, Su YT, Perng DS, Chen WH, Lin LJ, Chi SC, Chou CH. Effectiveness of a nurse-led management programme for paediatric asthma in Taiwan. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007;43:134–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]