Abstract

Background

Radical resection provides the best hope for cure in leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava (IVC). Multi-visceral resection is often indicated by extensive tumour involvement. This report describes the technical challenges encountered during resection of a retrohepatic IVC leiomyosarcoma.

Methods

Computed tomography showed an IVC leiomyosarcoma measuring 7.8 × 10.0 × 19.3 cm in a 41-year-old patient. The tumour reached the confluence of the hepatic veins, displacing the caudate lobe anteriorly and extending towards the IVC bifurcation inferiorly. En bloc resection of the IVC tumour with a right hepatic and caudate lobectomy, and a right nephrectomy was performed.

Results

Subsequent to a Cattel manoeuvre, the operative procedures carried out can be broadly categorized in four major steps: (i) mobilization of the infrahepatic IVC and tumour; (ii) mobilization of the suprahepatic IVC from diaphragmatic attachments; (iii) right hepatectomy with complete caudate lobe resection, and (iv) en bloc resection of the IVC tumour. This approach allowed the entire length of tumour-bearing IVC to be freed from the retroperitoneum and avoided the risk for iatrogenic tumour rupture during dissection at the retrohepatic IVC. Reconstruction of the IVC was not performed in the presence of venous collaterals.

Conclusions

Experience in liver resection and transplantation, and appreciation of the hepatocaval anatomy facilitate the safe and radical resection of retrohepatic IVC leiomyosarcoma.

Keywords: leiomyosarcoma, vena caval tumor, hepatic resection, liver resection, soft tissue sarcoma, inferior vena cava

Introduction

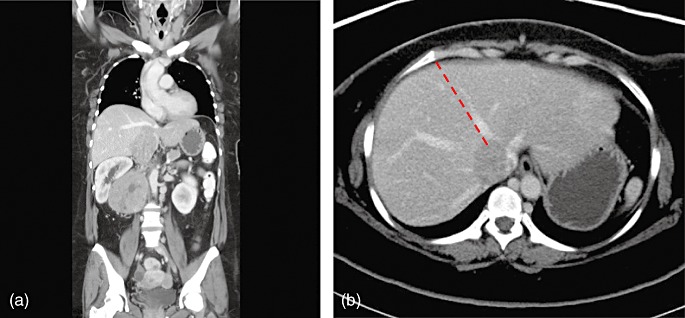

Primary leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava (IVC) is an exceedingly rare malignancy of which fewer than 300 cases are reported in the literature.1,2 Surgical resection remains the mainstay of treatment and complete gross tumour clearance is the key factor for longterm survival.3,4 This report describes the surgical approach taken in a 41-year-old woman with IVC leiomyosarcoma. Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed a right retroperitoneal tumour measuring 7.8 × 10.0 × 19.3 cm with direct IVC involvement (Fig. 1a). Cranially, the IVC tumour thrombus reached the confluence of the hepatic veins (Fig. 1b), compressing on the caudate lobe of liver anteriorly. Caudally, the tumour thrombus extended towards the IVC bifurcation. En bloc resection of the IVC tumour with a right hepatic and caudate lobectomy, and a right nephrectomy was performed. Technical considerations and the operative technique are described herein.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography images of the inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma, showing (a) a coronal view and (b) a cross-sectional view. The dashed red line denotes the hepatic transection plane

Operative details

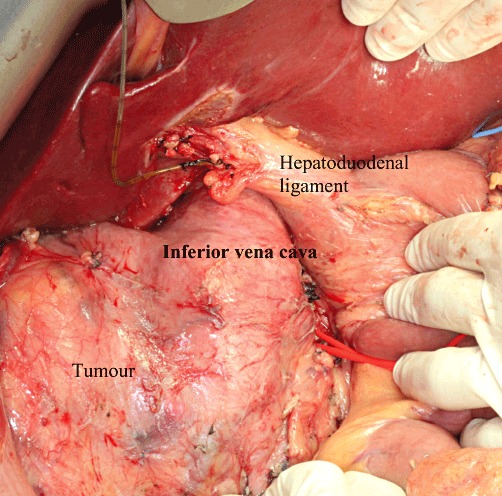

The abdomen was explored through a long midline incision from the subxyphoid to the infra-umbilical region with a right subcostal extension. A left subcostal incision was avoided in order to preserve the venous collaterals within the left rectus abdominis. A Bookwalter™ retractor (Codman & Shurtleff, Inc., Raynham, MA, USA) was used to maintain exposure of the operative field. A medial visceral rotation (Cattel manoeuvre) was performed to expose the anterior surface of the IVC and aorta (Fig. 2). The second part of the operation was broadly divided into four steps.

Figure 2.

Exposure of the inferior vena cava and tumour after kocherization of the duodenum

-

Mobilization of the infrahepatic IVC and tumour

First, the caudal extent of the IVC tumour and the line of transection were ascertained by intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS). Next, the anterior–medial surface of the aorta was dissected at the same level. All the lymphatic tissues covering the aorta were lifted and turned towards the IVC. The aortocaval window was then entered and the plane between the IVC tumour and the retroperitoneal surface came into view. It was necessary for dissection to remain close to the retroperitoneal surface until the right side of the IVC was reached. By skeletonizing the anterior–medial surface of the aorta in a cranial direction, the right renal artery and left renal vein were reached and exposed.

-

Exposing the suprahepatic IVC and hepatic vein confluence

The falciform ligament was divided until the anterior surface of the suprahepatic IVC was exposed. The junction between the origin of the middle hepatic vein (MHV) and the IVC was defined by sharp dissection. The cranial extent of the tumour and the patency of the MHV and left hepatic vein (LHV) were ascertained by IOUS. The left lateral section of liver was taken down from the diaphragm and the right liver was mobilized from the diaphragm after the division of the coronary and triangular ligament. Both the right and left diaphragmatic veins draining into the IVC were divided in order to lengthen the free segment of suprahepatic IVC so that a vascular clamp could be placed. The anterior surface of the suprahepatic IVC was freed from attachments to the diaphragmatic hiatus circumferentially until the right atrial pericardium was exposed.

-

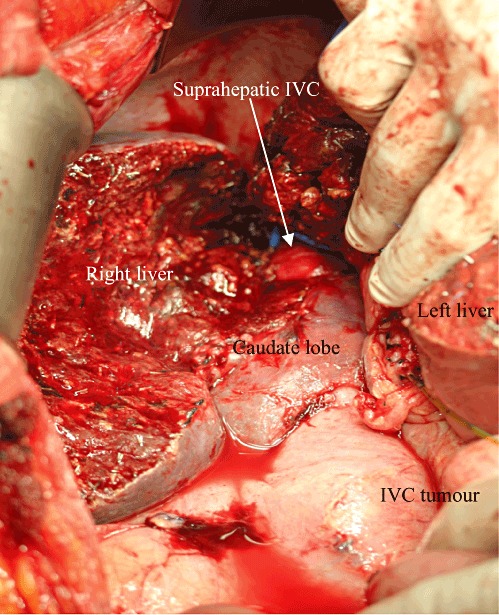

Right hepatectomy with complete caudate lobe resection

The right liver was mobilized until the right side of the retrohepatic IVC was exposed. As the tumour was firmly adhered to the caudate lobe, the retrohepatic IVC was removed en bloc with the right liver and caudate lobe. Hepatic parenchymal transection was performed using an ultrasonic dissector along the right side of the MHV. When the right liver was split from the left liver remnant at the level of the caudate lobe, the plane of transection was skewed horizontally towards the ligamentum venosum in the same manner as in harvesting an extended left lobe graft without the caudate lobe in a living donor liver transplantation (LDLT).5 This approach allowed the right liver and left caudate lobe to be completely separated from the left liver (Fig. 3).

-

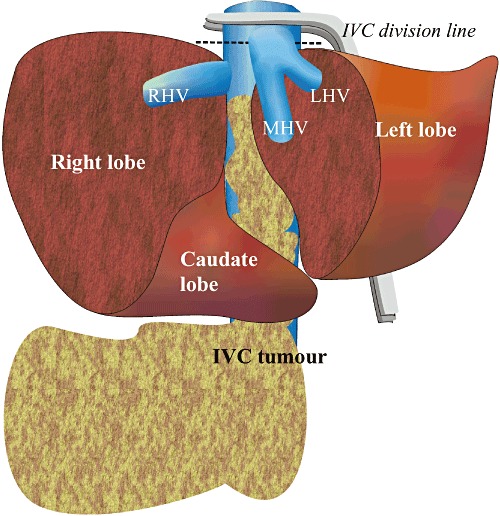

En bloc resection of the IVC tumour

The caudal end of the IVC was clamped and divided. The IVC tumour was then detached from the retroperitoneal surface and all the lumbar veins were divided. The right kidney was removed en bloc with the tumour. The left renal vein was sacrificed after confirmation of venous collaterals. The infrahepatic IVC was lifted cranially to the level of the hepatic vein confluences. A Pringle manoeuvre was performed to the left liver remnant and a vascular clamp (Ulrich Swiss AG, St Gallen, Switzerland) was applied across the suprahepatic IVC above the hepatic vein confluences. The cranial end of the IVC was divided inferior to the origin of the MHV (Fig. 4) and the tumour specimen was removed (Fig. 5). Selective total vascular occlusion to the left liver remnant substantially reduced backflow from the MHV and LHV and provided an almost bloodless field for tumour retrieval from the bevelled IVC stump. The latter was subsequently closed using continuous 5–0 Prolene. Caval reconstruction was not performed because of the chronicity of tumour thrombosis and the lack of haemodynamic instability during IVC cross-clamping. Patency of the MHV and LHV were reaffirmed by IOUS.

Figure 3.

Right hepatectomy with complete caudate lobe resection. IVC, inferior vena cava

Figure 4.

Graphic illustration of inferior vena cava (IVC) tumour resection. RHV, right hepatic vein; MHV, middle hepatic vein; LHV, left hepatic vein

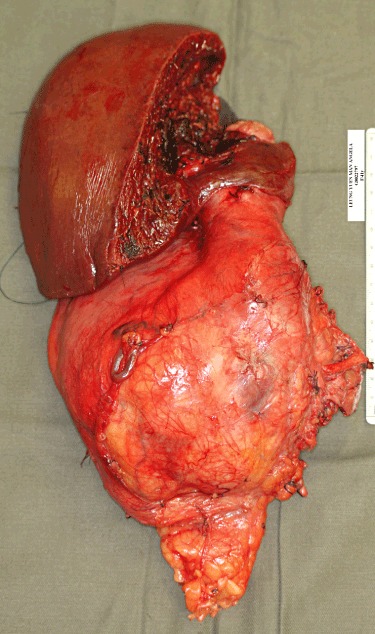

Figure 5.

Macroscopic appearance of the inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma

Postoperatively, renal and liver function normalized on days 3 and 14, respectively. There was no clinical sign of leg oedema throughout the postoperative course.

Discussion

Resectability determines longterm prognosis in IVC leiomyosarcoma and every effort should be made to achieve tumour clearance. The technical challenges in this operation relate to the mobilization of the tumour from the retroperitoneal surface and the control of suprahepatic IVC. Experience in liver transplantation, especially in LDLT, that familiarizes the operating surgeon with the surgical approach to the vena cava (e.g. mobilization of the suprahepatic IVC and dissection of the hepatic vein confluences) is helpful in this situation. In the present case, direct mobilization of the infrahepatic IVC was deemed difficult because of the outgrowth of tumour-feeding vessels and the unclear plane between the IVC and the retroperitoneal surface. The approach described here allowed all tissues on the right side of the aorta to be cleared away and the plane between the IVC and the retroperitoneal surface to be defined within the aortocaval window. A major advantage of this manoeuvre is that it avoids iatrogenic tumour rupture during the mobilization of the IVC and inadvertent tearing of the tumour-feeding vessels running across the aortocaval window. Moreover, all lymphatic drainage to the IVC tumour can be effectively cleared away.

Another technical consideration concerns how to approach the retrohepatic IVC. In this context, separating the caudate lobe from the tumour-engorged IVC might easily result in iatrogenic tumour rupture. Furthermore, control of the retrohepatic branches of hepatic veins will be challenging because operative space in this area is limited. Any bleeding caused by tearing of the deep retrohepatic veins during mobilization of the caudate lobe would be difficult to control. The advantage of a right hepatectomy combined with a complete caudate lobectomy is that the IVC tumour is removed en bloc with the right liver and the potential risks associated with mobilization of the retrohepatic IVC become negligible. Moreover, splitting the right and left liver apart improves access to the suprahepatic IVC and hence facilitates the placement of an Ulrich Swiss clamp.

The necessity for IVC reconstruction remains controversial. Potential benefits of restoring IVC continuity include the prevention of leg oedema and the preservation of venous drainage to the kidney. However, IVC reconstruction is associated with graft-related complications such as infection and thrombosis,6 risk for pulmonary embolism arising from deep vein thrombosis in the lower extremities, and the need for longterm anticoagulation. Nonetheless, the decision in the present case to omit IVC reconstruction was justified by the absence of postoperative leg oedema and early restoration of normal renal function.

Conclusions

Experience in liver resection and transplantation, and a clear understanding of the hepatocaval anatomy facilitates the safe and radical resection of IVC leiomyosarcoma.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Mingoli A, Cavallaro A, Sapienza P, Di Marzo L, Feldhaus RJ, Cavallari N. International registry of inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma: analysis of a world series on 218 patients. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:3201–3205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hilliard NJ, Heslin MJ, Castro CY. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: three case reports and review of the literature. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2005;9:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiore M, Colombo C, Locati P, Berselli M, Radaelli S, Morosi C, et al. Surgical technique, morbidity, and outcome of primary retroperitoneal sarcoma involving inferior vena cava. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:511–518. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1954-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalkat MS, Abedin A, Rooney S, Doherty A, Faroqui M, Wallace M, et al. Renal tumours with cavo-atrial extension: surgical management and outcome. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2008;7:981–985. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2008.180026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan ST, Wei WI, Yong BH, Hui TWC, Chiu A, Lee PWH. Living Donor Liver Transplantation. 2nd edn. Raffles City: World Scientific; 2011. pp. 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirohashi K, Shuto T, Kubo S, Tanaka H, Tsukamoto T, Shibata T, et al. Asymptomatic thrombosis as a late complication of a retrohepatic vena caval graft performed for primary leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: report of a case. Surg Today. 2002;32:1012–1015. doi: 10.1007/s005950200204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]